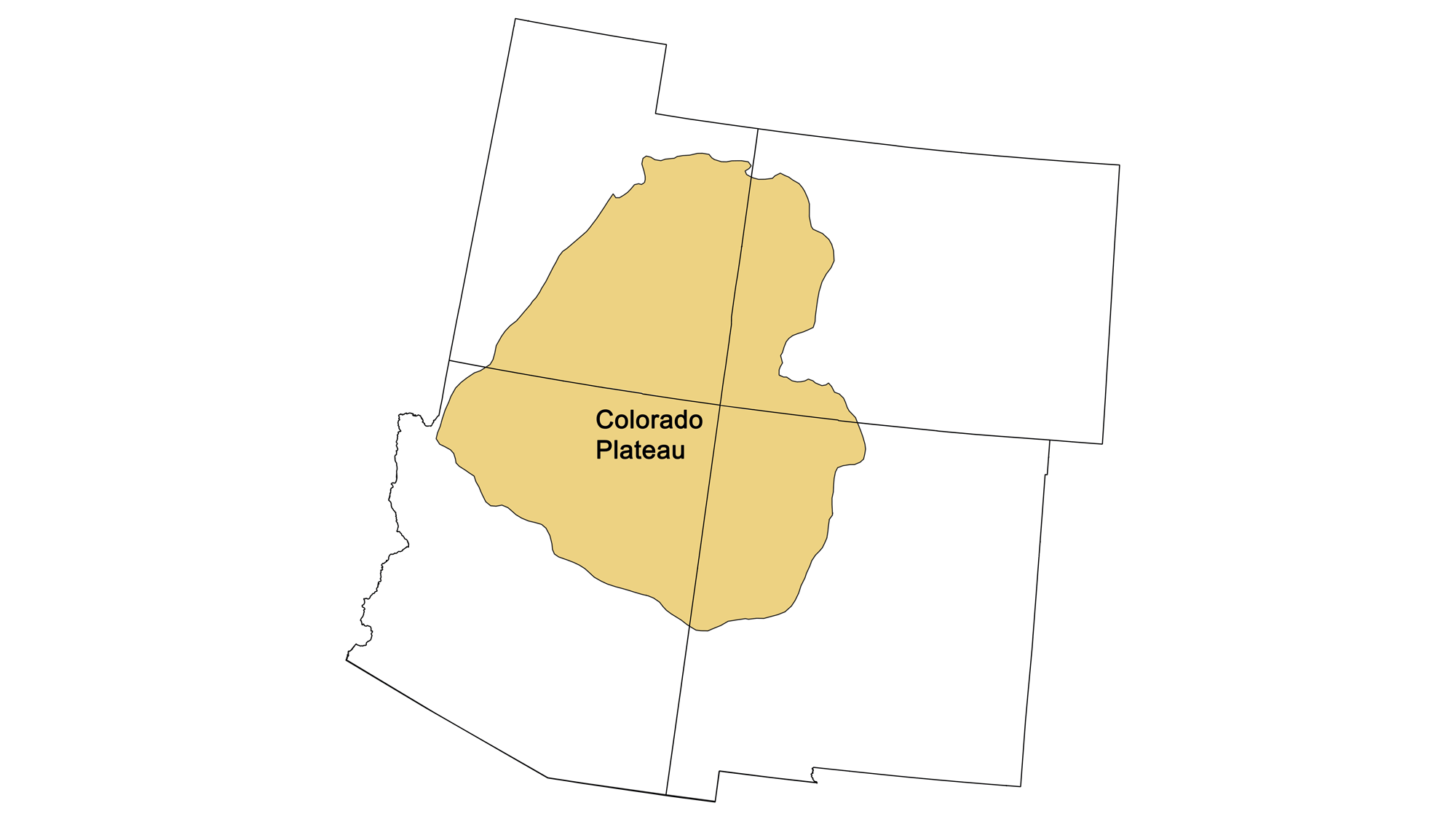

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Colorado Plateau region of the southwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Precambrian fossils; Paleozoic fossils; Cambrian fossils; Ordovician to Devonian fossils; Carboniferous fossils; Permian fossils; Triassic fossils; Chinle Formation (Triassic); Jurassic fossils; Early Jurassic fossils; Late Jurassic fossils (Morrison Formation); Dinosaur National Monument; Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry; Cretaceous fossils; Early Cretaceous fossils; Late Cretaceous fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Paleocene fossils; Eocene fossils; Quaternary fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Southwestern US" by Warren D. Allmon and Richard A. Kissel, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 14, 2022.

Image above: Agate house, a structure made from petrified wood, at Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. This house dates to sometime between 1050 to 1300. Source: Petrified Forest National Park, National Park Service (public domain).

Precambrian fossils

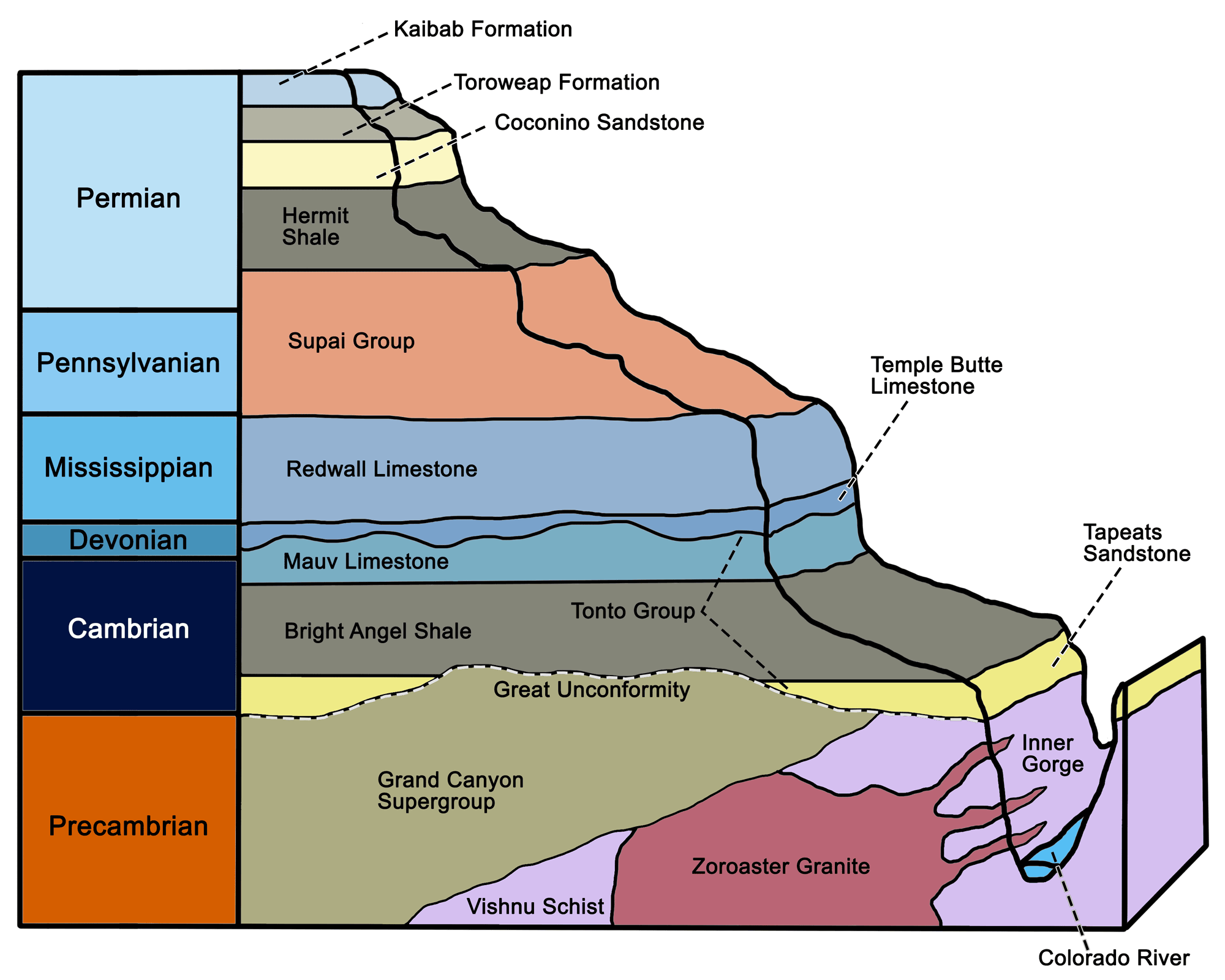

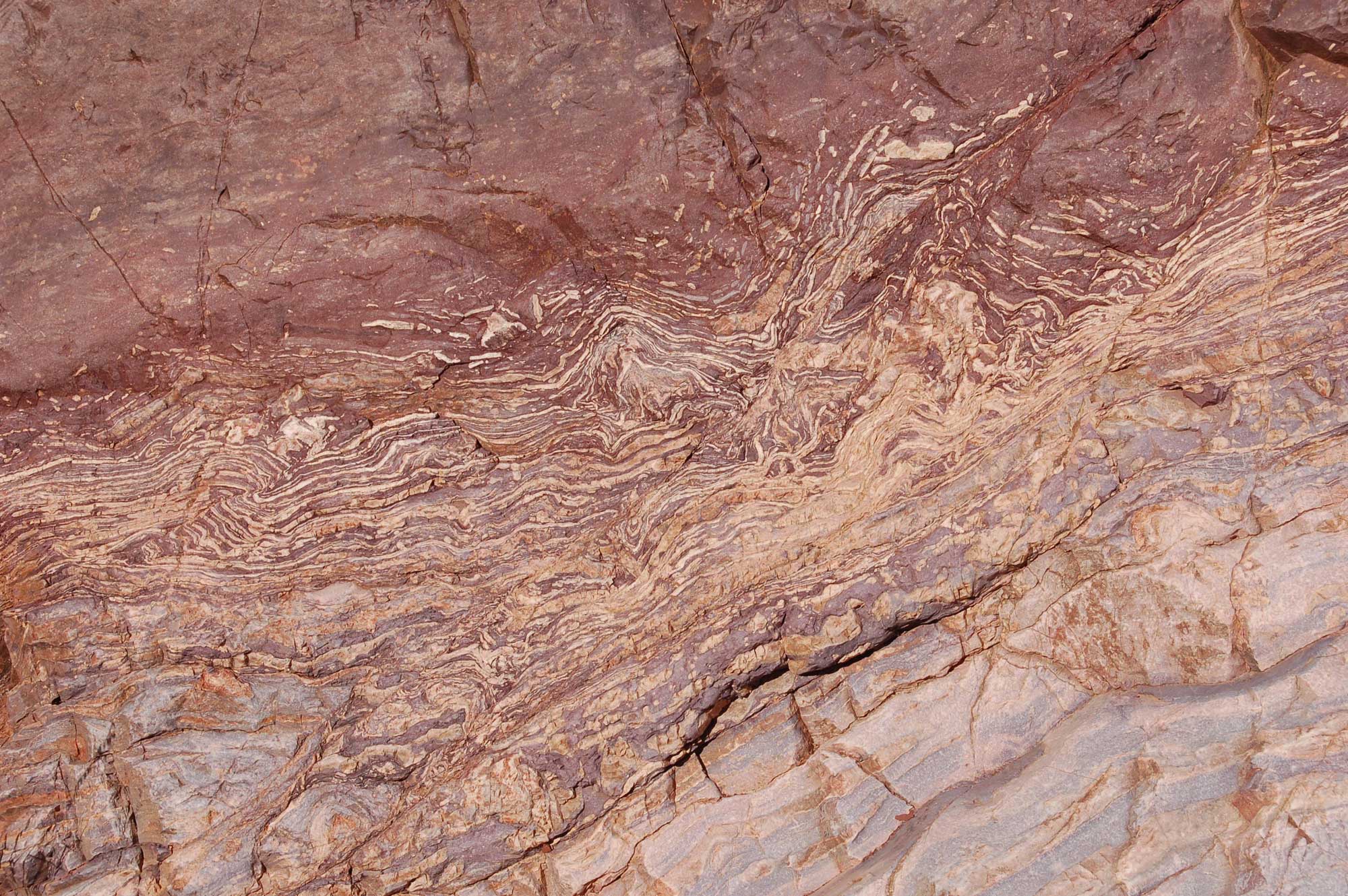

The rocks of the Colorado Plateau represent a diversity of environmental conditions over hundreds of millions of years. These rocks are well exposed in the many canyons that occur across this region, most spectacularly in the Grand Canyon in northern Arizona. The oldest fossils known from the Colorado Plateau region are stromatolites, which are layered domes of carbonate sediment formed by mats of photosynthetic bacteria known as cyanobacteria. These are found in a layer called the Bass Limestone, exposed near the bottom of the Grand Canyon. They stromatolites date to the mid-Proterozoic, around 1.2 billion years ago.

Late Proterozoic rocks known as the Chuar Group (around 740 million years old) contain a variety of microfossils. Most are referred to as acritarchs, which are spherical objects 1–5 millimeters in diameter. Acritarchs are thought by many paleontologists to be the resting form of single-celled algae. Several levels within the Chuar Group also contain stromatolites. Stromatolites are layered structures formed by photosynthetic bacteria called cyanobacteria.

Major Proterozoic and Paleozoic stratigraphic units of the Grand Canyon and Colorado Plateau. Modified from a diagram by Wade Greenberg-Brand originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Precambrian stromatolites in the Bass Limestone, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. NPS photo by Carl Bowman (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Paleozoic fossils

Cambrian fossils

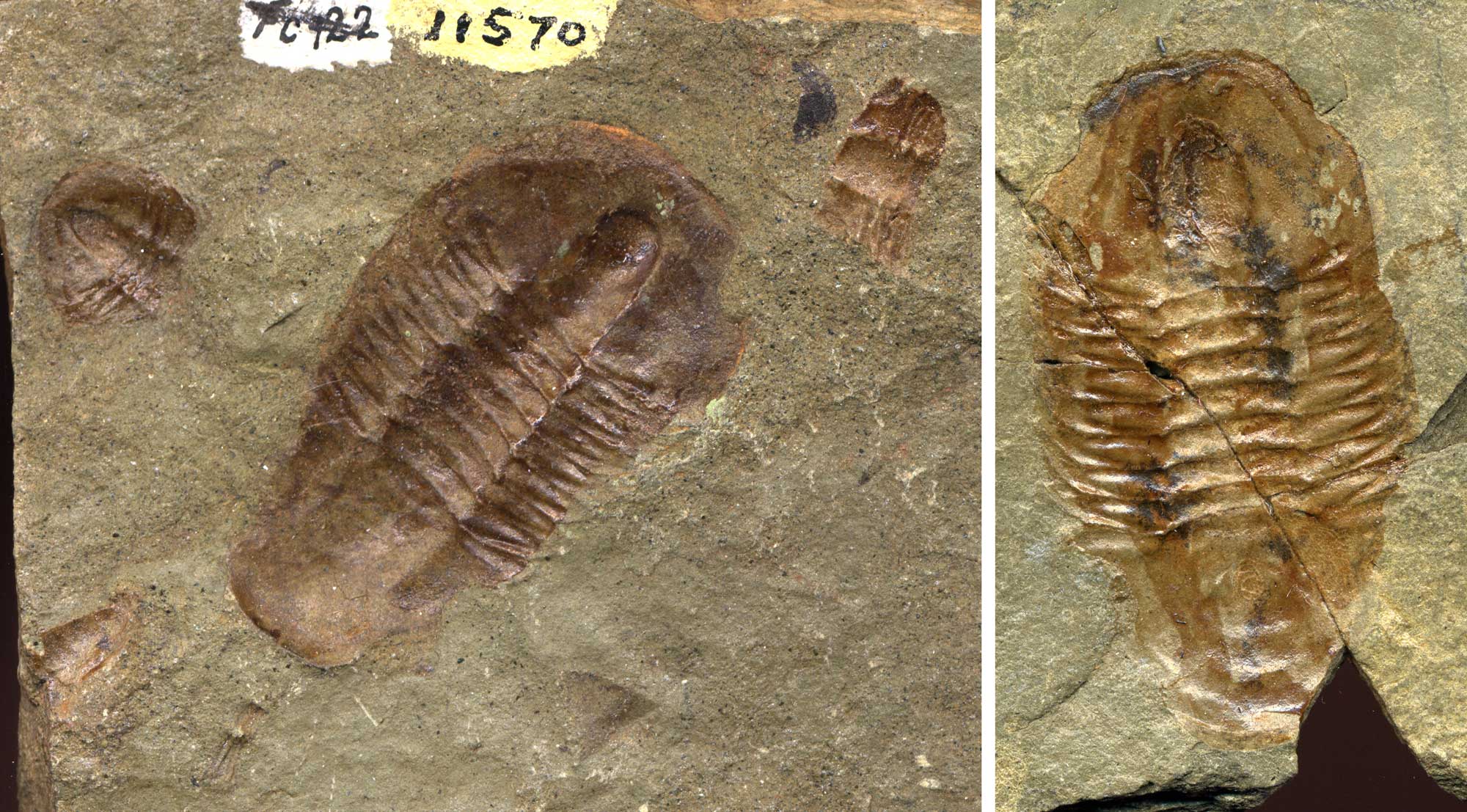

The earliest Phanerozoic sediments recorded in the Grand Canyon area are known as the Tonto Group. The fossils in these rocks are usually not very well preserved, but they come in great variety, dominated by trilobites, of which more than 50 species have been reported. Brachiopods are also frequently found in these rocks, and, more rarely, sponges and echinoderms similar to those found in the Cambrian of western Utah.

Trace fossils from Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Left: Cruziana, a type of trace fossil attributed to trilobites. Formation not identified, but probably Cambrian Tonto Group. (Length about 20 centimeters or 8 inches). Photo by Cassi Knight, Paleontology Guest Scientist (National Park Service, public domain). Right: Trace fossils (burrows and Cruziana) from the Cambrian Bright Angel Shale, Tonto Group. Photo by Cassi Knight, Paleontology Guest Scientist (National Park Service, public domain).

Cambrian trilobites from the Bright Angel Shale (Tonto Group), Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Left: Trilobites identified as Dolichometoppus productus and Alokistocare althea. Right: Dolichometoppus productus. Left photo and right photo by NPS/Michael Quinn (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Ordovician to Devonian fossils

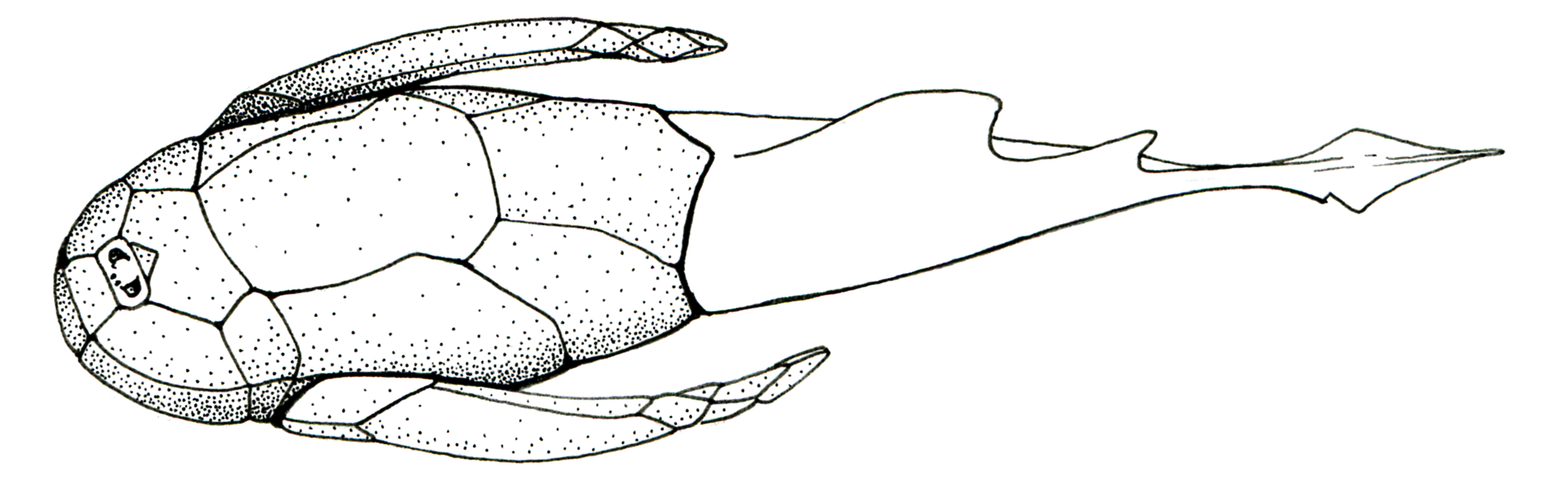

Ordovician and Silurian rocks are absent in the southern part of the Colorado Plateau. Devonian rocks are present in the area, but are only moderately fossiliferous. The Devonian Temple Butte Formation, exposed in the Grand Canyon, contains poorly preserved brachiopods, corals, crinoids, and also occasionally the remains of placoderms—an extinct group of fishes that dominated the waters of the Devonian. Their name means “plated skin,” and they were characterized by bony armor covering the front part of the body and pectoral fins.

Fragments of the bottom-dwelling placoderm Bothriolepis have been recovered from Devonian rocks in northern and central Arizona, and in central Colorado, northwest of Denver (in Eagle and Garfield counties). Placoderms became extinct during a mass extinction event near the end of the Devonian period. Conodonts—small, primitive, eel-like vertebrates—are also known from Devonian and later rocks throughout the region.

Carboniferous fossils

Mississippian fossils

Mississippian rocks exposed in the Grand Canyon, including the Redwall Limestone and Surprise Canyon Formation, contain abundant brachiopods, corals, bryozoans, gastropods, bivalves, nautiloid cephalopods, crinoids, and shark teeth. In at least one Redwall locality, straight-shelled nautiloids more than 60 centimeters (24 inches) long have been found.

Tabulate corals from the Mississippian Redwall Limestone, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Left photo and right photo NPS photos by Michael Quinn (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Marine invertebrates from the Mississippian Redwall Limestone, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona; on the left is a bryozoan, on the right a brachiopod. Left photo and right photo NPS photos by Michael Quinn (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Pennsylvanian fossils

Some Pennsylvanian layers in the Colorado Plateau also accumulated in terrestrial environments, including swamps, rivers, lakes, and floodplains. The Mississippian to Pennsylvanian Surprise Canyon Formation contains layers with terrestrial plant fossils, including lycophytes, calamites (an extinct group related to horsetails), marattioid ferns, and seed ferns.

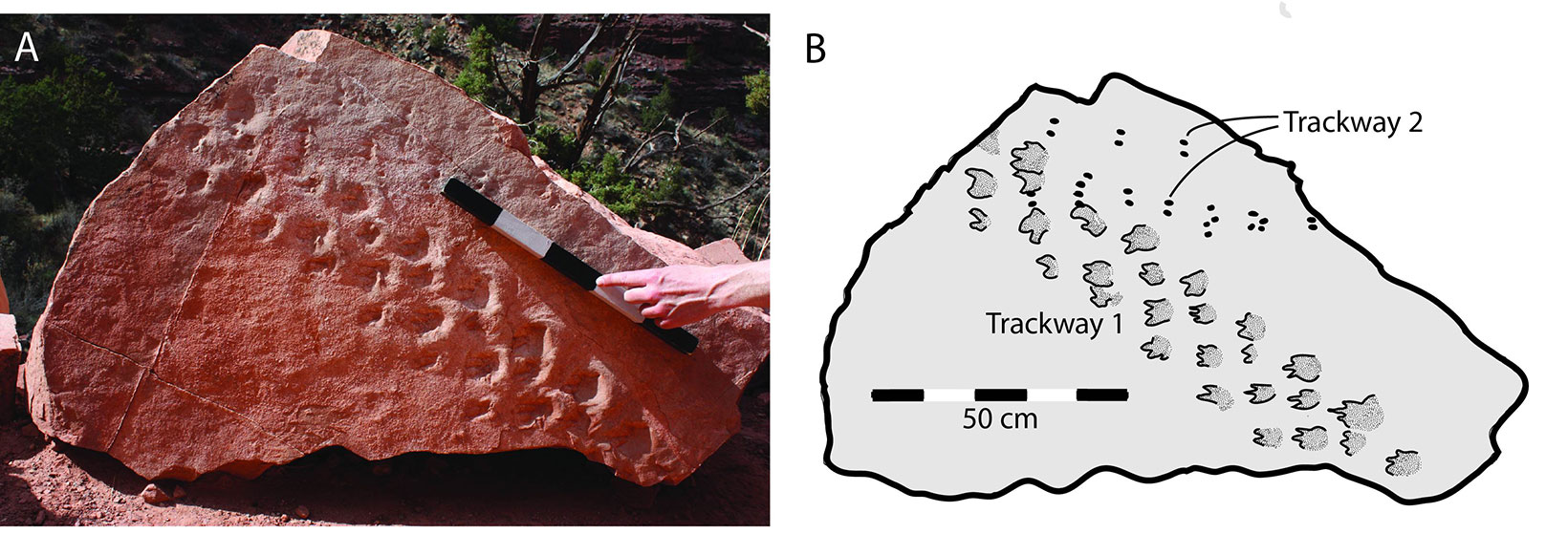

Pennsylvanian to Permian marine rocks in the southern Colorado Plateau include the Supai Group in northern Arizona and the Honaker Trail Formation in southern Utah. In the Grand Canyon and the surrounding area, the Supai Group contains trace fossils (burrows, trackways, and other marks) in almost all layers. In 2020, the oldest tracks of amniotes (the group of animals including reptiles, birds, and mammals) in the Grand Canyon were described from the Pennsylvanian Manakacha Formation of the Supai Group. A number of beds also contain abundant and diverse shelly fossils, including brachiopods and foraminifera.

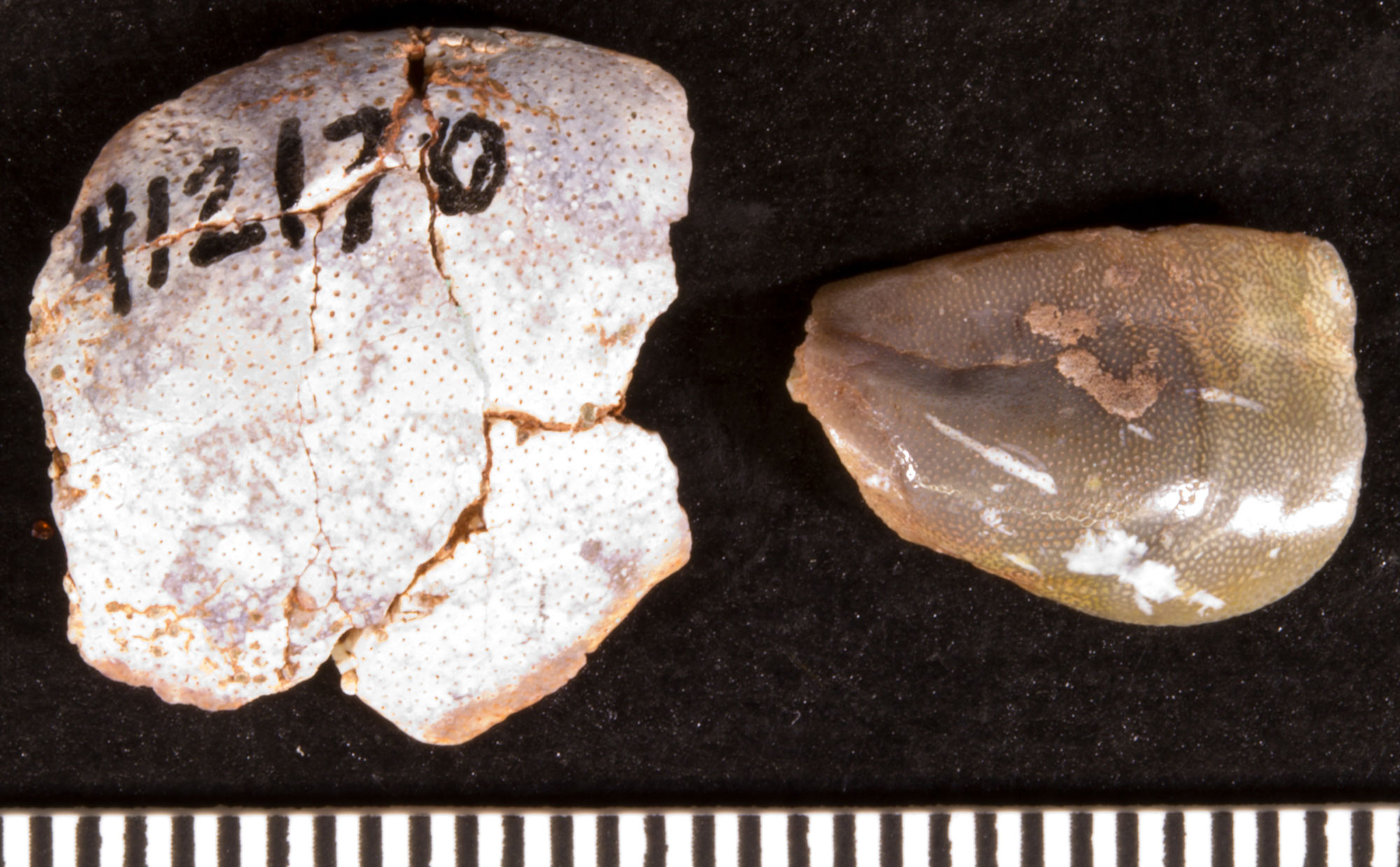

Tooth of Deltodus, an ancient relative of the chimaera (a type of cartilaginous fish related to sharks), from the Mississippian Surprise Canyon Formation, Supai Group, Arizona. Photo of specimen USNM PAL 412170 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Pennsylvanian vertebrate tracks from the Manakacha Formation, Supai Group, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Photo of the tracks (A) and drawing of the same specimen (B). Scale is in decimeters (1 decimeter = 10 centimeters = about 3.9 inches). Figures 2A and 2B from S. M. Rowland, M. V. Caputo, and Z. A. Jensen (2020) PLoS ONE 15(8): e0237636 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Permian fossils

Permian terrestrial fossils

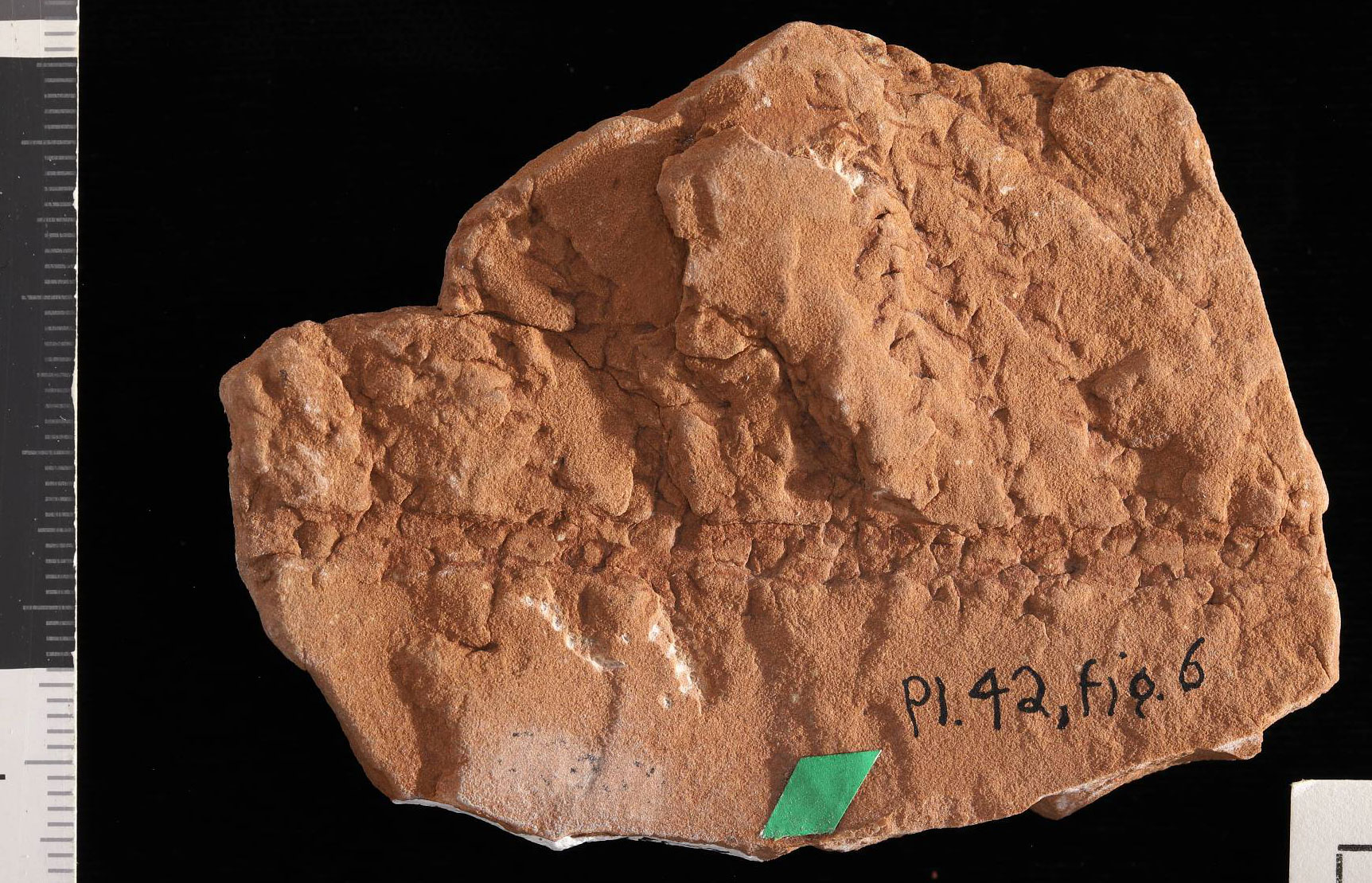

Permian rocks of the Grand Canyon region contain terrestrial fossils. The Hermit Formation yields fossil plants. The overlying Coconino Sandstone is a 90-meter-thick (300-foot-thick) terrestrial deposit, with cross-bedded layers that are characteristic of sand dunes. More than 20 types of vertebrate footprints have been identified within this unit, made by a variety of amphibians and reptiles that trekked through damp sand some 280 million years ago. A variety of other tracks are attributed to arthropods, including spiders, scorpions, beetles, and millipedes.

One of the most important deposits of early Permian vertebrate fossils in North America is known from the El Cobre Canyon Formation (Culter Group) in the Arroyo del Agua area, west of Abiquiu, Rio Arriba County, in northern New Mexico. This site has produced the skeletal remains of many large terrestrial amphibians and reptiles, including Sphenacodon, Eryops, Ophiacodon, and Diadectes. Eryops and the sail-backed predator Dimetrodon are also abundant in the Permian rocks of southern Utah, including Monument Valley and the Valley of the Gods. The small reptile Seymouria is found in Permian rocks south of Moab, Utah.

Unidentified seed fern fronds (leaves) from the Permian Hermit Shale, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Left photo and right photo by Michael Quinn (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Branches and leaves of an ancient conifer (Walchia dawsonii), Permian Hermit Shale, Arizona. Photo of USNM P 38052 by Frederic Cochard (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Vertebrate tracks in the Permian Coconino Sandstone, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Photo by Michael Quinn (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Vertebrate tracks (Ichnotherium), Permian Coconino Sandstone, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Photo by Cassi Knight, Paleontology Guest Scientist (public domain).

Permian marine fossils

Above the Coconino Sandstone is another Permian marine unit, the Kaibab Limestone, which contains abundant fossils from marine vertebrates and invertebrates, including brachiopods, sponges, corals, crinoids, echinoids, gastropods, bivalves, nautiloid and ammonoid cephalopods, conodonts, and shark teeth. Ammonoid cephalopods are especially important for biostratigraphy in this and other Permian marine layers.

Marine invertebrate fossils (a brachiopod on the left, segments of crinoid stalks on the right) from the Permian Kaibab Formation, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Left photo and right photo by Michael Quinn/NPS (Grand Canyon National Park via flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Fossil nautiloid (Tainoceras schellbachi) from the Permian Kaibab Limestone, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Model by National Park Service Geologic Resources Division (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license).

Triassic fossils

Early and middle Mesozoic rocks (Triassic and Jurassic periods) of the Colorado Plateau are just as fossil rich as Paleozoic-aged rocks. The Triassic rocks of northern Arizona are famous for their fossils of terrestrial (land-dwelling) and freshwater vertebrates. The middle Triassic Moenkopi Formation contains one of the best vertebrate fossil assemblages of this age anywhere in the world, including abundant bones and trackways of both large amphibians and reptiles. Skeletal remains in the Moenkopi include freshwater sharks, coelacanths, and lungfish, as well as amphibians, rhynchosaur reptiles, and the non-dinosaur archosaur Arizonasaurus.

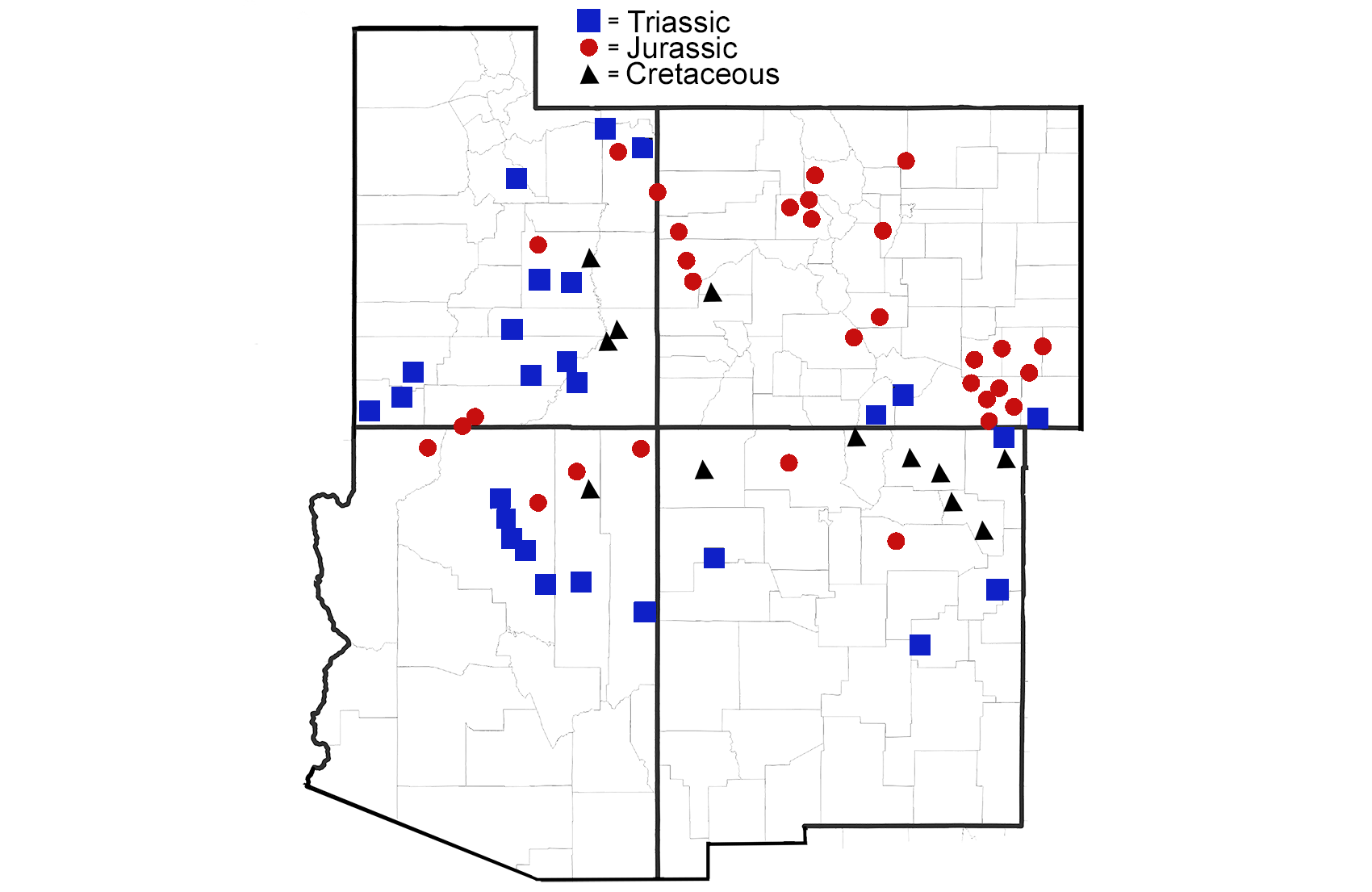

Major localities in which Mesozoic footprints (mostly dinosaurs) have been found. Map modified from a map by Alana McGillis that was compiled from multiple sources. Originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Chinle Formation

The late Triassic Chinle Formation (or Group) is exposed across much of the Southwest. This formation accumulated in a shifting set of habitats, from forests to rivers and lakes.

Fossils of freshwater aquatic animals

Fossils of freshwater fish, clams, and crustacean burrows are common in parts of the Chinle Formation, suggesting abundant water, but other evidence indicates that rainfall was probably highly seasonal, and the environment was frequently dry. Fossil fishes found here include the coelacanth Chinlea, the shark Xenacanthus, the lungfish Ceratodus, and Australosomus, a relative of today’s goldfish and tuna.

Fossil lungfish toothplate, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Formation and age not specified, but probably Triassic Chinle Formation. Photo by U.S. National Park Service (NPS, public domain).

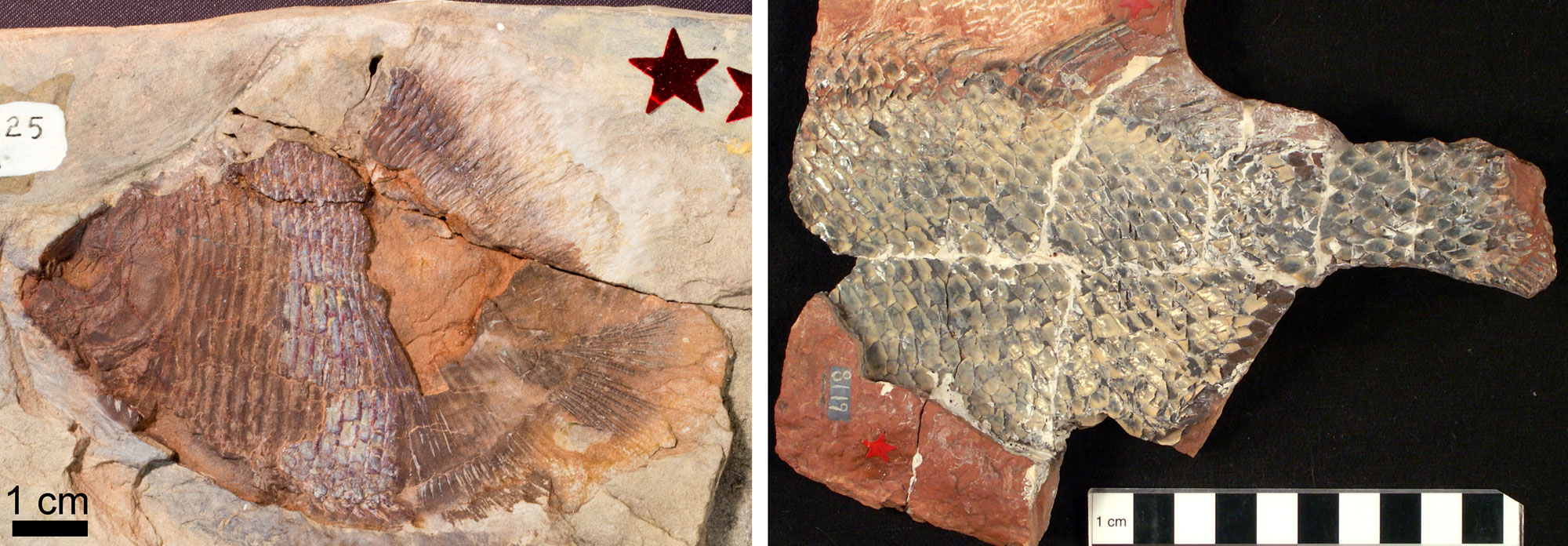

Fossil ray-finned fish, Triassic, Utah. Left: Hemicalypterus weiri, Chinle Formation, San Juan County. Photo of USNM V23425 (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain). Right: Lepidotus walcotii, Kanab Valley. Photo of USNM V8119 (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Fossil clams, Triassic Chinle Formation, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Photo by NPS (U.S. National Park Service, public domain).

Terrestrial animal fossils

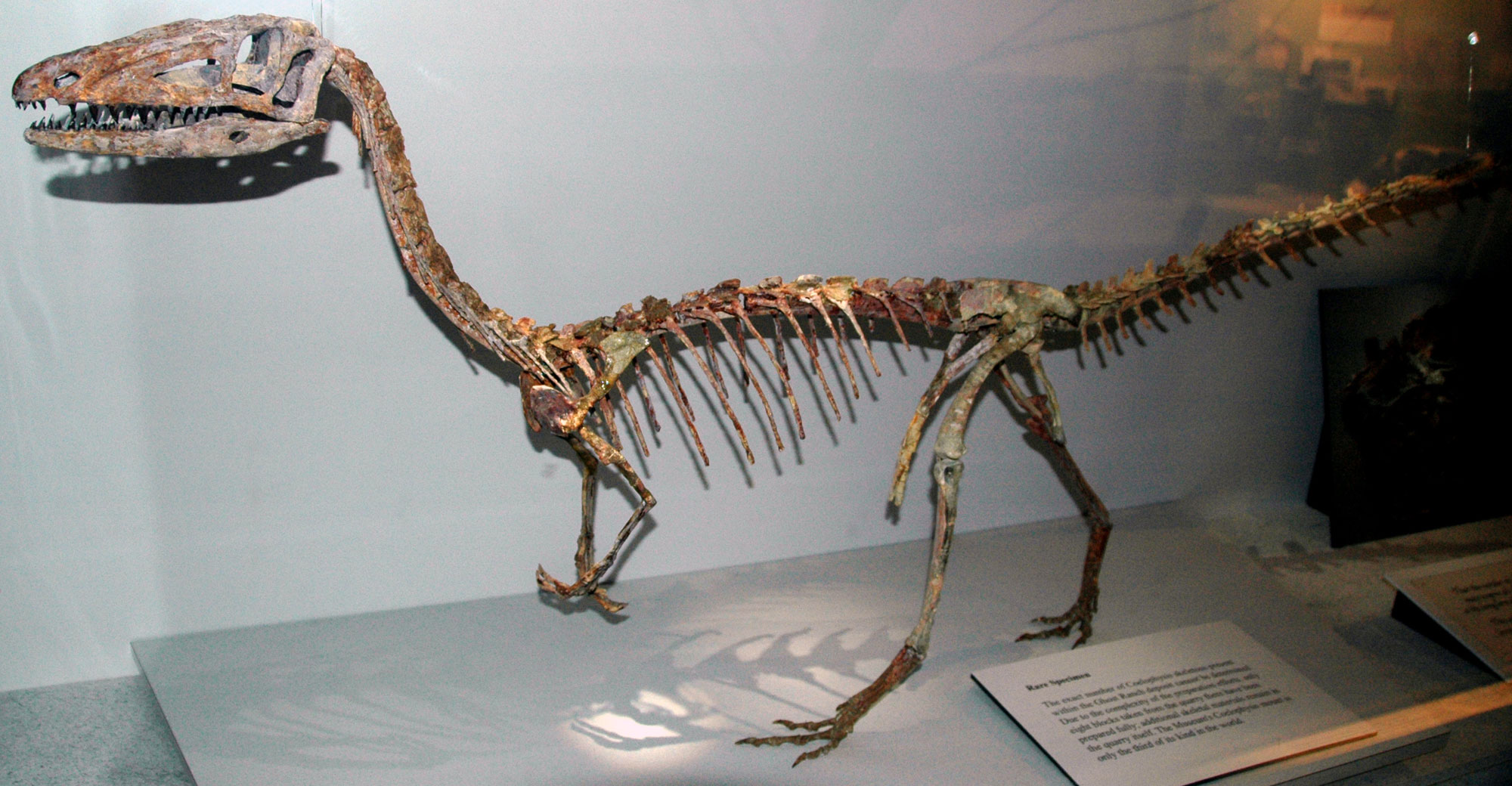

Terrestrial animals include a parade of forms, such as the bizarre armored reptiles known as aetosaurs (for example, Desmatosuchus), the rauisuchid Postosuchus, the synapsid (mammal-like reptile) Placerias, crocodile-like phytosaurs (the most common vertebrate in the formation), and the small theropod dinosaur Coelophysis.

In the 1940s, hundreds of Coelophysis skeletons were discovered at Ghost Ranch in Rio Arriba County, north-central New Mexico. This fossil treasure trove may have formed when the dinosaurs died around a shrinking water source during the dry season, and then were swept up and deposited by a flash flood. The study of fossils from this deposit helped to make Coelophysis one of the world’s best-known dinosaurs.

Display of vertebrate skeleton casts (reproductions) at Petrified Forest National Park, including the carnivorous rauisuchid Postosuchus (background/upper), the aetosaur Desmatosuchus (foreground/lower) and a pterosaur (on the back of the Desmatosuchus). Photo by Marine 69-71 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

The synapsid (mammal-like reptile) Placerias from the Triassic Chinle Formation, cast (reproduction skeleton) on display at Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Photo by NPS/Hallie Larson (National Park Service, public domain).

Upper part of the skull of a phytosaur (Smilosuchus gregorii), Triassic Chinle Formation, Apache County, Arizona. Photo of specimen USNM V18313 (Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Coelophysis baueri, a small theoropod dinosaur from the Triassic Chinle Formation, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Block of Coelophysis specimens collected in 1948 at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Photo by Paleeoguy (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Terrestrial plant fossils

The Chinle is also famous for its fossil trees, spectacularly exposed in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park and also abundant in the surrounding region. Most wood preserved in this region belongs to the conifer species Araucarioxylon arizonicum. Other plants include lycophytes, ferns, cycads, cycadeoids, other conifers, and ginkgoes.

A pile of large logs from the Triassic Chinle Formation, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Most fossil wood at the park is assigned to a species of conifer (Araucarioxylon arizonicum). Photo by T. Scott Williams (National Park Service, public domain).

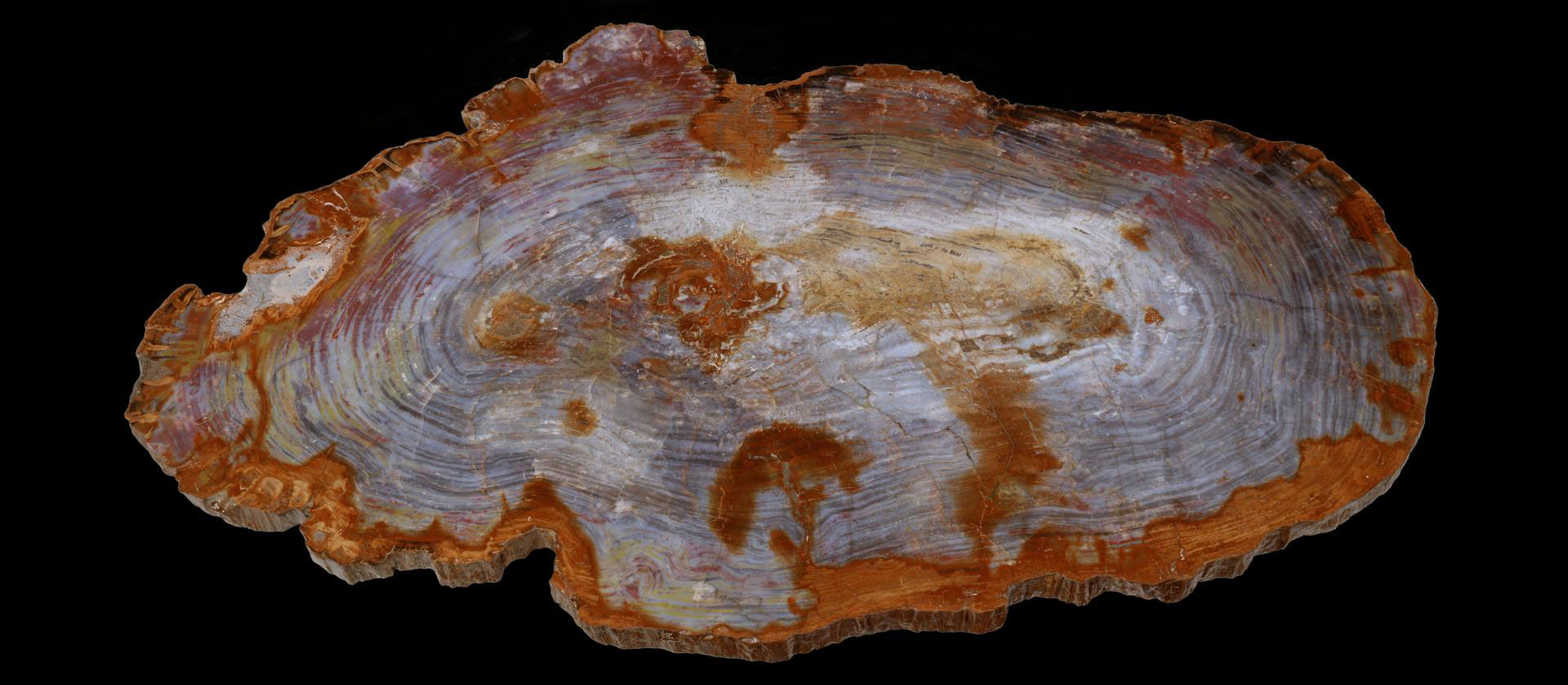

Cross section of a conifer (Araucarioxylon arizonicum) trunk, Triassic Chinle Formation, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Photo of specimen YPM PB 045161 by William K. Sacco, 2003 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, image accessed via GBIF.org).

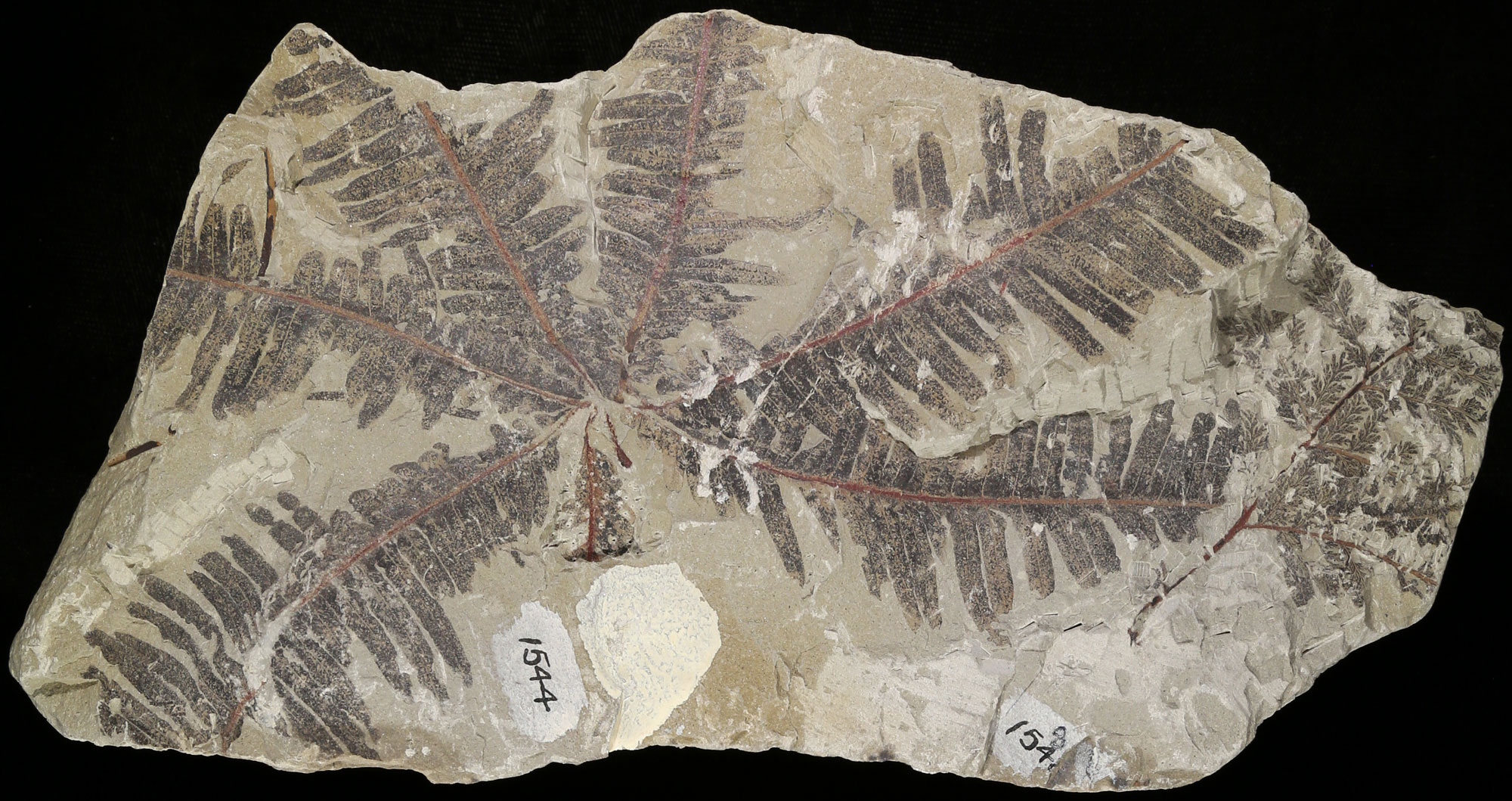

Fronds of leptosporangiate ferns (left, Phlebopteris smithii; right, Wingatea plumosa) from the Triassic Chinle Formation, Apache County, Arizona. Photo of specimens UCMP 1544 and UCMP 1548 by Diane Erwin (University of California Museum of Paleontology, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, via GBIF.org; image cropped and resized).

Fronds of a fern (left, Cladophlebis daughertyi) from the Triassic Chinle Formation, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Photo source: National Park Service (public domain).

Jurassic fossils

Early Jurassic fossils

The Jurassic Kayenta Formation overlies the Chinle Formation and is exposed in the Painted Desert and vicinity in norther Arizona. It contains fossils of early mammal relatives as well as dinosaurs, including the larger theropod Dilophosaurus. One type of synapsid, or mammal-like reptile, discovered in the Kayenta Formation Kayentatherium wellesi, an animal reminiscent of a large woodchuck. In 2000, remains of an adult Kayentatherium was found with skulls of 38 juveniles; in 2018, a report interpreted these remains as a mother with her young.

Although it was once desert dune sand, the overlying Navajo Sandstone also contains dinosaurs and trackways.

The predatory dinosaur Dilophosaurus wetherilli from the Early Jurassic Kayenta Formation, Coconino County, Navajo Nation, Arizona. Left: Reconstruction of the holotype (name-bearing) specimen, on display at the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, Canada). Photo by Eduard Solà (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized). Right: Reconstruction of the animal by Leandra Walters. Note that it is has no frill, which was an addition made for the movies. Drawing by Leander Walters in P. Senter and J. H. Robins (2015) PLoS ONE 10(12): e0144036 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Kayentatherium wellesi from the Early Jurassic Kayenta Formation of Arizona. Left: Skull. Right: A complete skeleton. The ruler is about 15 centimeters (6 inches) in length. Photos of specimen USNM PAL 31702 by Michael Brett Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Department of Paleobiology, public domain).

Ornithopod-type tracks, Powell Fossil Track Block Tracksite, Jurassic Navajo Sandstone, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona and Utah. Photo source: National Park Service (public domain).

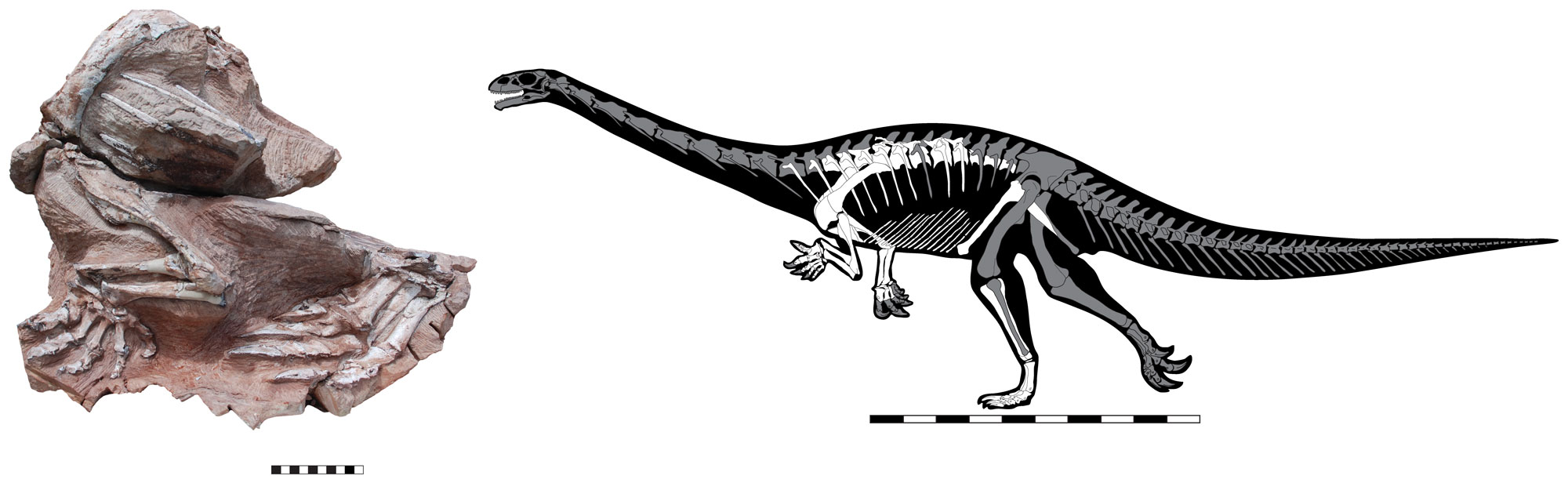

A prosauropod (Seitaad ruessi, a relative of sauropods) from the Early Jurassic Navajo Sandstone, San Juan County, Utah. Left: Portion of the skeleton showing two feet. Scale bar = 10 centimeters (3.6 inches). Figures 1C and 3A from J. J. W. Sertich and M. A. Lowewen (2010) PLoS ONE 5(3): e9789 (Creative Commons Attribution license, images cropped and reconfigured). Right: Reconstruction of the skeleton and silhouette of the animal; bones in white were actually discovered, bones in dark gray are inferred. Scale bar = 1 meter (39.4 inches).

Late Jurassic fossils

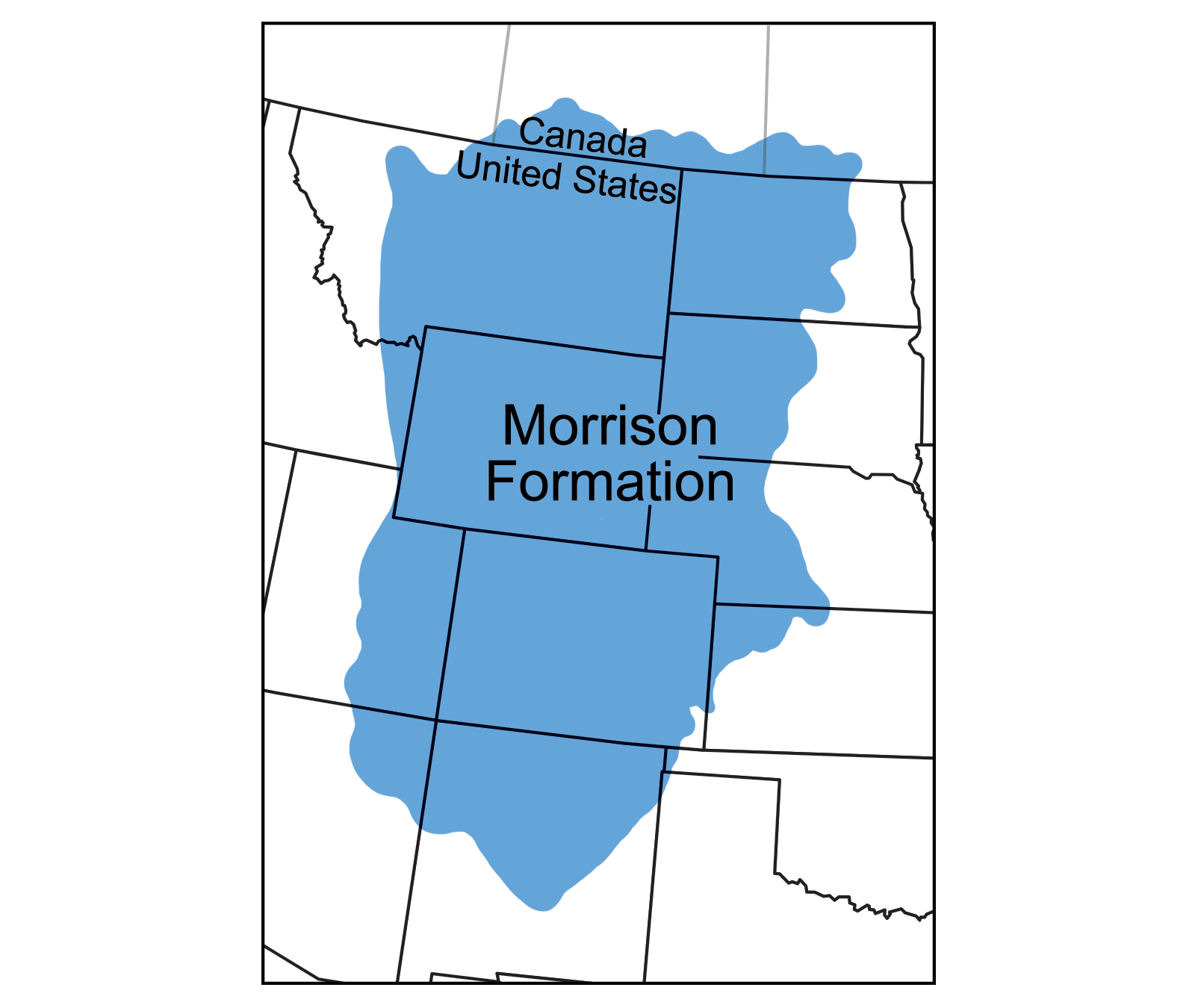

As the Jurassic continued, dinosaurs continued to expand in diversity and size. Their dominance is abundantly demonstrated in the Jurassic Morrison Formation, an extensive layer of rock that crops out in all four states of the Southwest, as well as in the Dakotas, Montana, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Idaho. Although the Morrison Formation contains more than 90 known species of fossil vertebrates, including fish, turtles, amphibians, and early mammals, it is most famous for its abundance and diversity of dinosaurs. Dinosaurs from the Morrison include carnivorous theropods such as Ceratosaurus and Allosaurus, herbivores such as Dryosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Camptosaurus, and gigantic long-necked sauropods, such as Amphicoelias, Apatosaurus, Barosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus.

The Morrison Formation also contains abundant plant fossils, including horsetails, ferns, seed ferns (seed plants with fern-like leaves), cycadeoids, ginkophytes, and conifers. These fossils suggest that the Morrison ecosystem was a mosaic of river, lake, and floodplain environments developed on an enormous alluvial plain covered by sediment eroding from the ancestral Rocky Mountains.

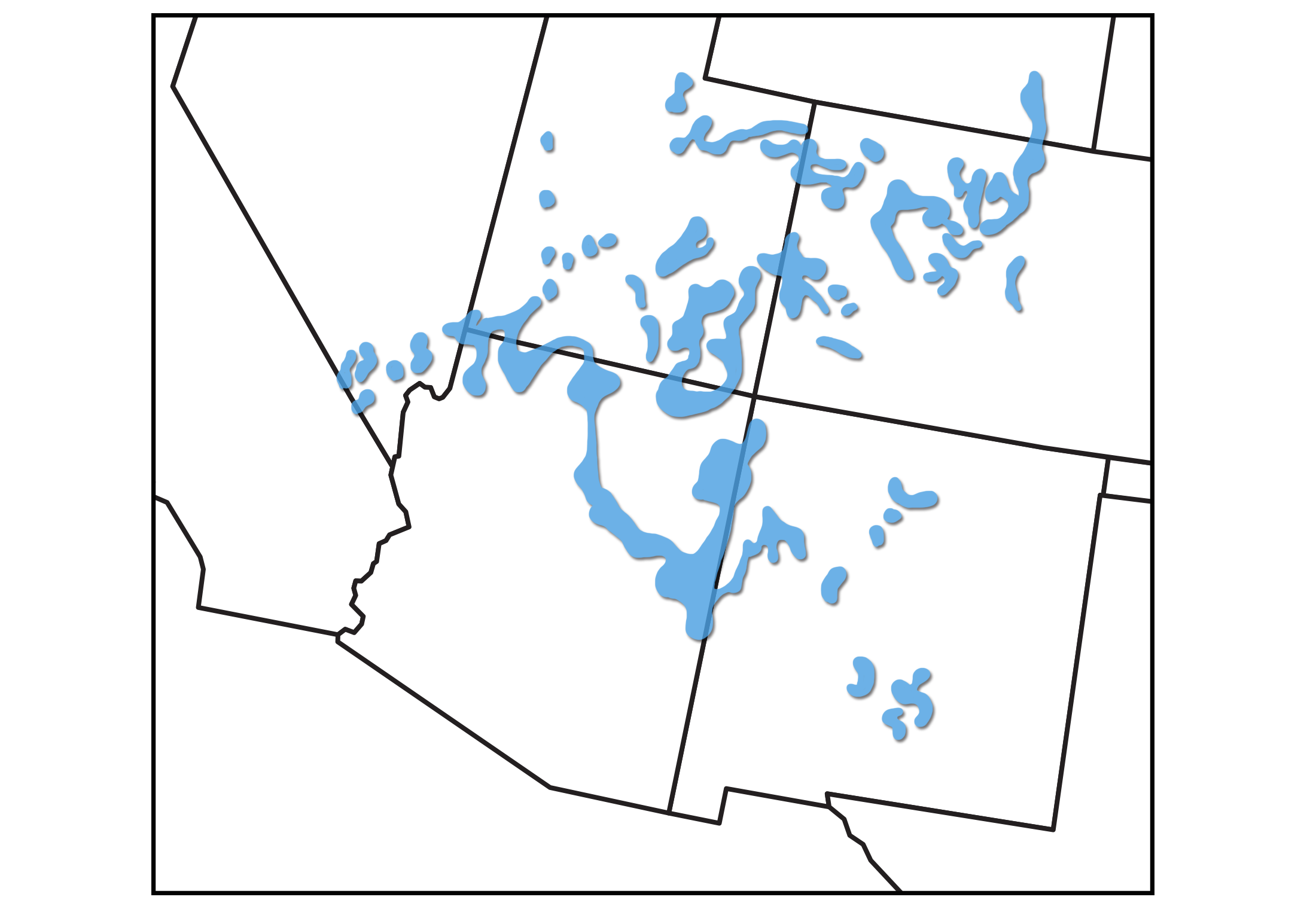

Geographic extent of the Jurassic Morrison Formation. Map modified from a map by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Ceratosaurus cast (reproduction skeleton) on display at the Natural History Museum of Utah (Salt Lake City). Original from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Jurassic Morrison Formation, Utah. Photo by Jens Lallensack (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Stegosaurus ungulatus from the Jurassic Morrison Formation, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah and Colorado. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Photo by Perry Quan (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Life-size paper mache model of Stegosaurus that was built for the 1904 St. Louis World's fair. The model, which depicts antiquated ideas about the posture of this dinosaur, was displayed at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History for nearly a century. It is now on permanent exhibit at the Paleontological Research Institution's Museum of the Earth. Learn more here. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Skeleton of Apatosaurus louisae, a type of sauropod, from the Carnegie Quarry, Jurassic Morrison Formation, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah and Colorado. On display at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Petrified log at Escalante Petrified Forest State Park, Jurassic Morrison Formation, Garfield County, Utah. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Dinosaur National Monument

Two spectacular places to see these dinosaur fossils still in place are Dinosaur National Monument, on the border between Utah and Colorado, and the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah. The dinosaur fossil beds in Dinosaur National Monument were discovered in 1909 by a paleontologist working for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Over several years, crews from the museum excavated thousands of fossil bones and shipped them back to Pittsburgh for study and display. The famous "Wall of Bones", located within the monument’s main building, consists of a steeply tilted rock layer containing hundreds of dinosaur bones. The layer was tilted by the Laramide Orogeny millions of years after the dinosaurs lived, died, and were buried.

The site was declared a national monument in 1915, but new discoveries continue to this day. In 2009, the tracks of tiny Jurassic mammals were found. In late 2015, one of the oldest known pterosaurs was found in the monument’s Triassic rocks.

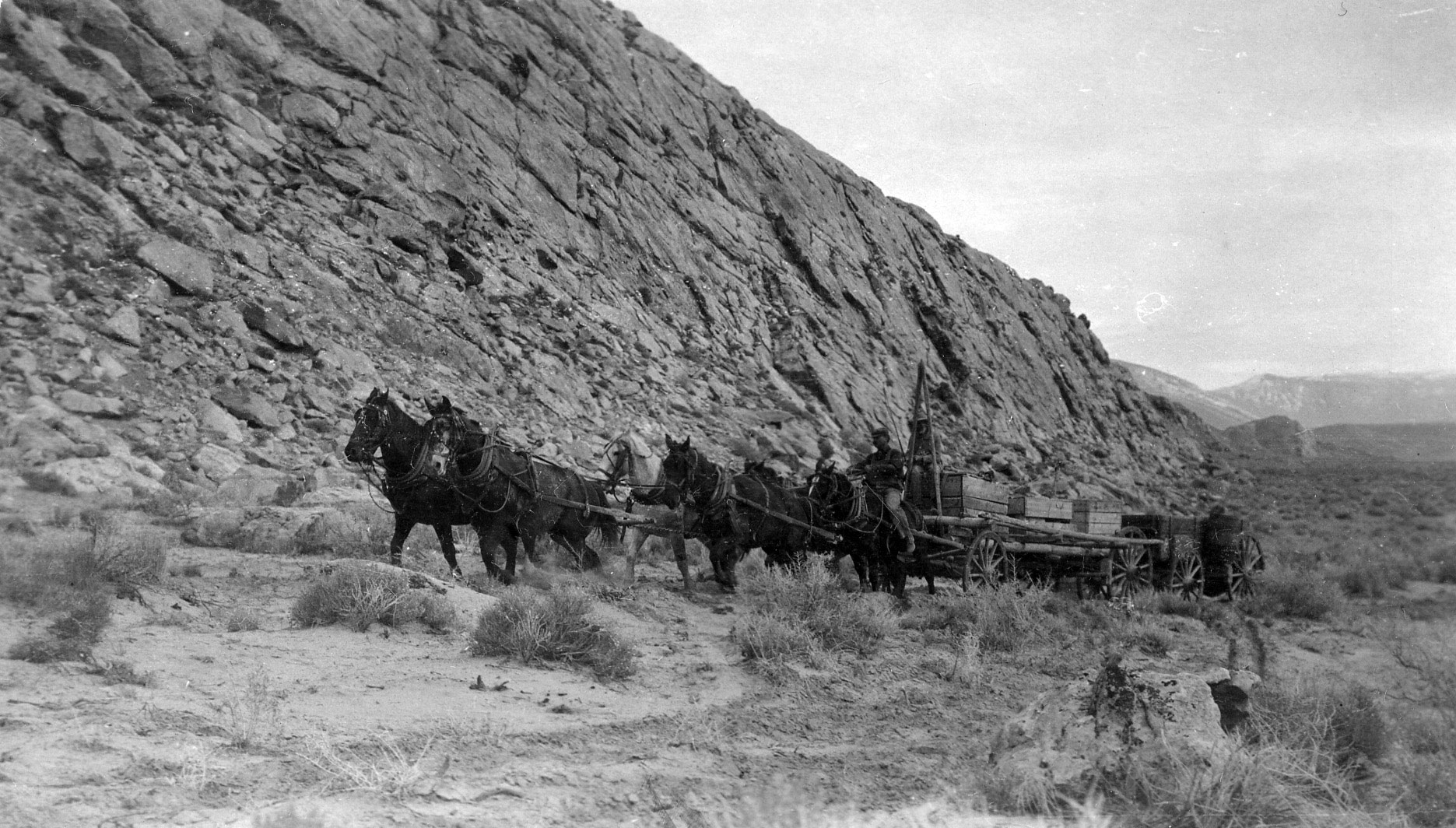

Excavated bones being transported away from Carnegie Quarry by a team of horses and a wagon. Date not specified. Photo by NPS/Earl Douglass Diaries, edited by Evan Hall (National park Service, public domain).

Wall of bones at Dinosaur National Monument, Utah and Colorado. Left: A geoscientists-in-the-Parks paleontology assistant inventorying fossils, 2019. Photo source: NPS (National Park Service, public domain). Right: A geoscientist photographing bones, 2012. NPS photo by Ashley Dineen, GIP (National Park Service, public domain).

Skeleton of a juvenile Camarosaurs lentus, a type of sauropod, from the Carnegie Quarry, Jurassic Morrison Formation, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah and Colorado. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Jurassic track of a mammal estimated to be 190 million years old. This track was discovered at Dinosaur National Monument in 2009. Photo source: U.S. National Park Service (public domain).

Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry

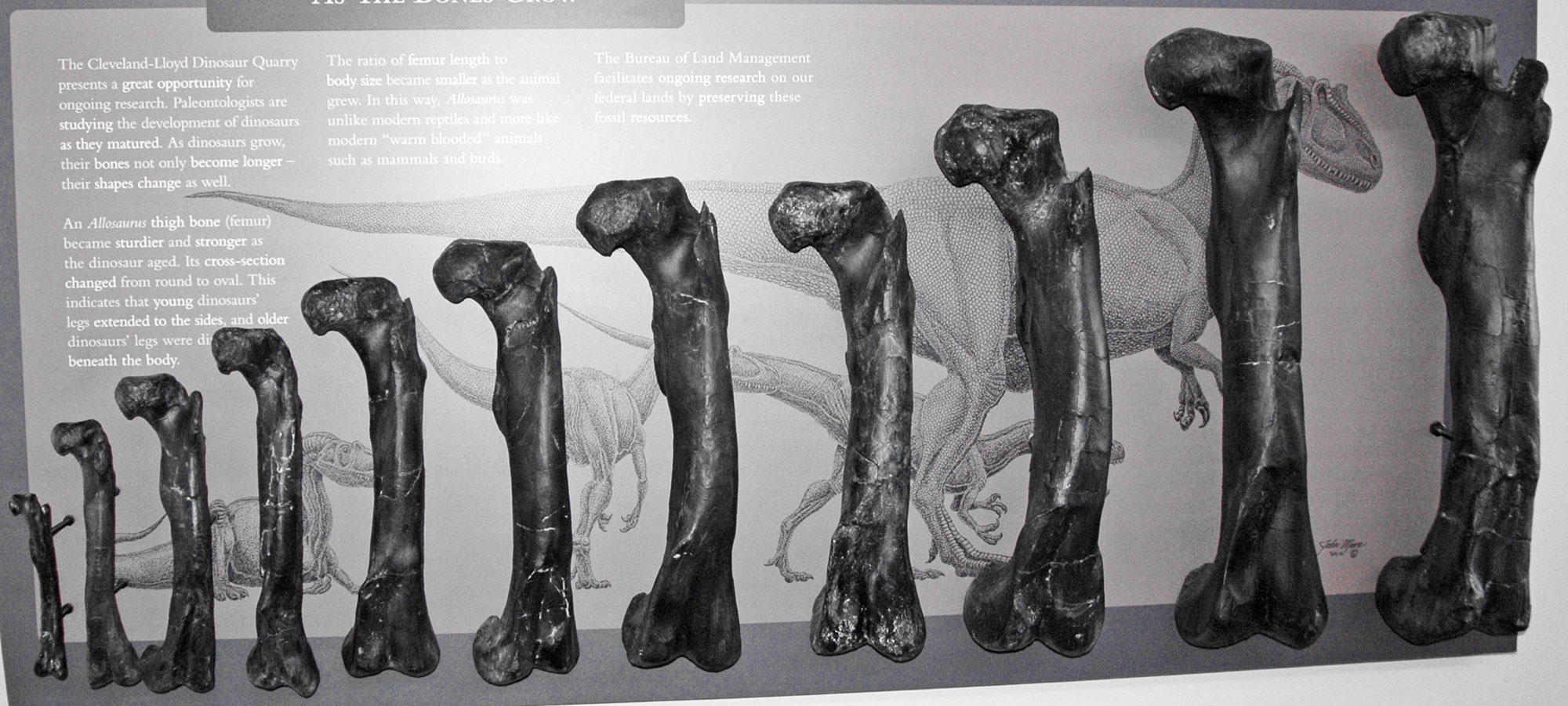

The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, located in northern Emery County, Utah, contains the densest concentration of Jurassic-aged dinosaur bones ever found. Over 10,000 bones belonging to at least 74 individual dinosaurs have been excavated at the quarry. Curiously, more than 70% of these bones come from carnivores, primarily Allosaurus fragilis. With more than 46 individual specimens of Allosaurus, scientists have been able to both deduce how Allosaurus aged and compare individuals to better understand variation within the species.

Exhibit at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Utah, showing bones and equipment as they would have existed during excavation. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Allosaurus fragilis on display at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Utah. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Growth series of Allosaurus femurs on display at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Utah. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Cretaceous fossils

Early Cretaceous to earliest Late Cretaceous terrestrial animals

Fossils from the Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah include a wide variety of dinosaurs. The fossil-bearing rocks of the formation span more than 20 million years of time, from at least about 125 to 120 million years ago to 98 million years ago. Thus, fossils from much of the formation (Yellow Cat, Poison Strip, and Ruby Ranch members) are Early Cretaceous in age, whereas the youngest fossils, which are from the Mussentuchit Member, may be late Early Cretaceous to earliest Late Cretaceous in age.

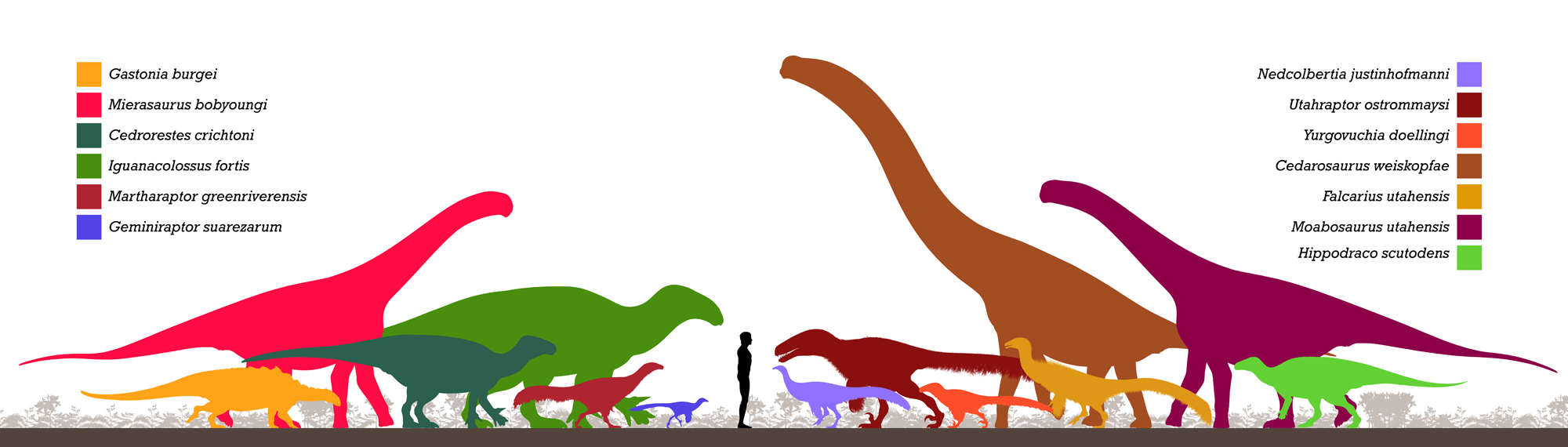

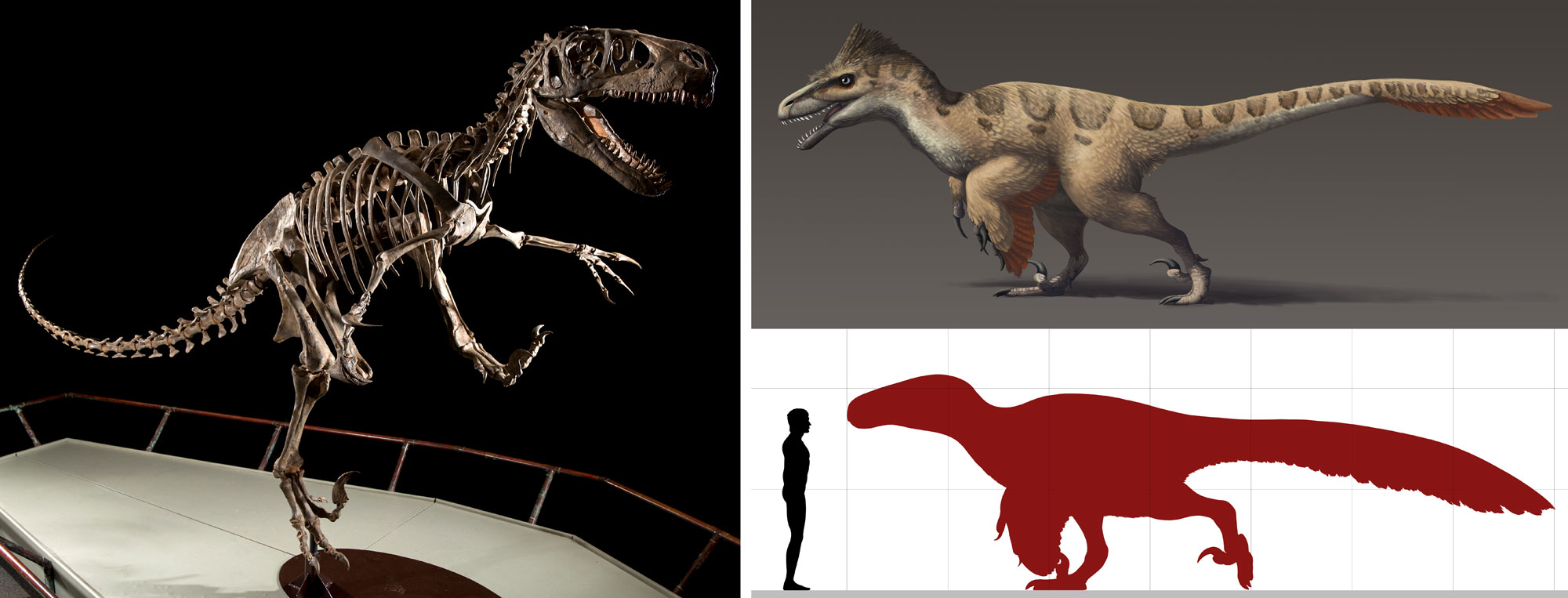

Dinosaurs from the Cedar Mountain Formation include herbivores (plant-eaters) like ankylosaurs (armored dinosaurs), hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), ornithopods, and sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs). There are also a variety of predatory theropods, including the large and ferocious-looking Utahraptor. Utahraptor is a type of dromaeosaur, a group of dinosaurs closely related to birds. Dromaeosaurs had a sickle-like claw on the inner toe of each foot. Scientists think that they used this claw to attack their prey. Utahraptor is the largest known dromaeosaur. It grew to as much as 6 to 7 meters (20 to 23 feet) long. In contrast, Velociraptor, a dromaeosaur from Mongolia, reached only about 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length.

The Mill Canyon Dinosaur Tracksite in Moab, Utah, preserves dinosaur tracks from the Cedar Mountain Formation. (Unfortunately, this tracksite sustained damage during a project to replace a walkway in 2022.) Fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals have been found in the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation.

Silhouettes showing the diversity and relative sizes of dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous Yellow Cat Member, Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah. These dinosaurs are about 125 to 120 million years old. Diagram by PaleoNeolithic (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Utahraptor, a theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Grand County, Utah. Left: Skeleton (cast or repoduction) on display at the Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University (Provo, Utah). Photo illustration by Jaren Wilkey/BYU (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized). Upper right: Reconstruction of living animal by Emily Willoughby (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized). Lower right: Silhouette of the living animal (about 7 meters or 23 feet long) compared to the size of an adult man (about 1.8 meters or 6 feet tall). Drawing by PaleoNeolitic (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

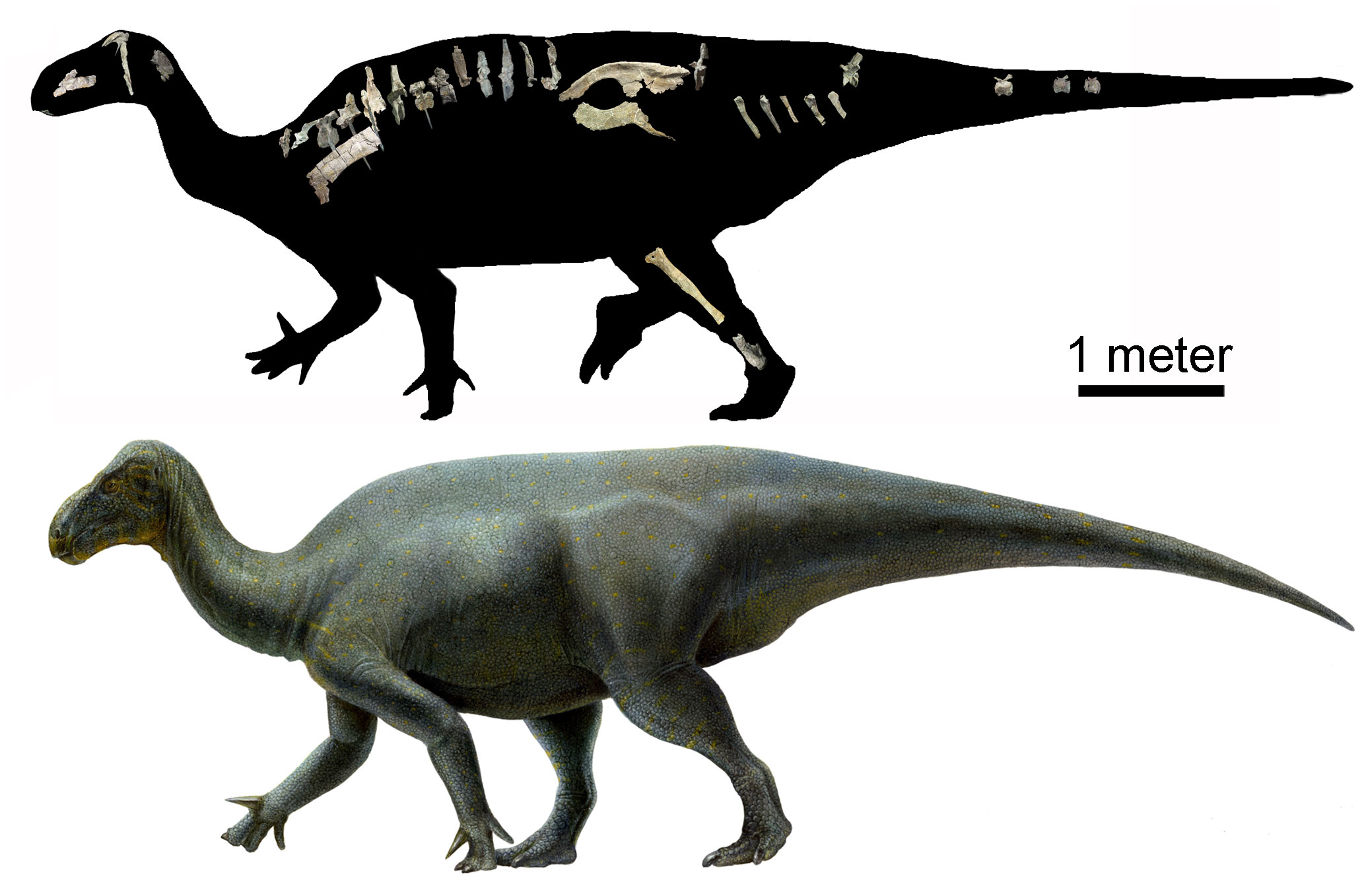

Iguanacolossus fortis, a hadrosaur from the Yellow Cat Member, Cedar Mountain Formation, Grand County, Utah. Top: Silhouette of the animal with bones that were actually found overlain. Bottom: Reconstruction of the living animal by Lukas Panzarin. Source: Figure 3 from McDonald et al. (2010) PLoS ONE 5(11): e14075 (public domain, image slightly modified from original).

Skull of the sauropod Abydosaurus mcintoshi from the Cretaceous Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation, about 98 million years old. Specimen on display at Dinosaur National Monument, Utah. Photo by James St. John (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

The ankylosaur Animantarx ramaljonesi from the Late Cretaceous Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation, about 98 million years old. Specimen on display at the Utah State University Eastern Prehistoric Museum (Price, Utah). Photo by Jens Lallensack (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

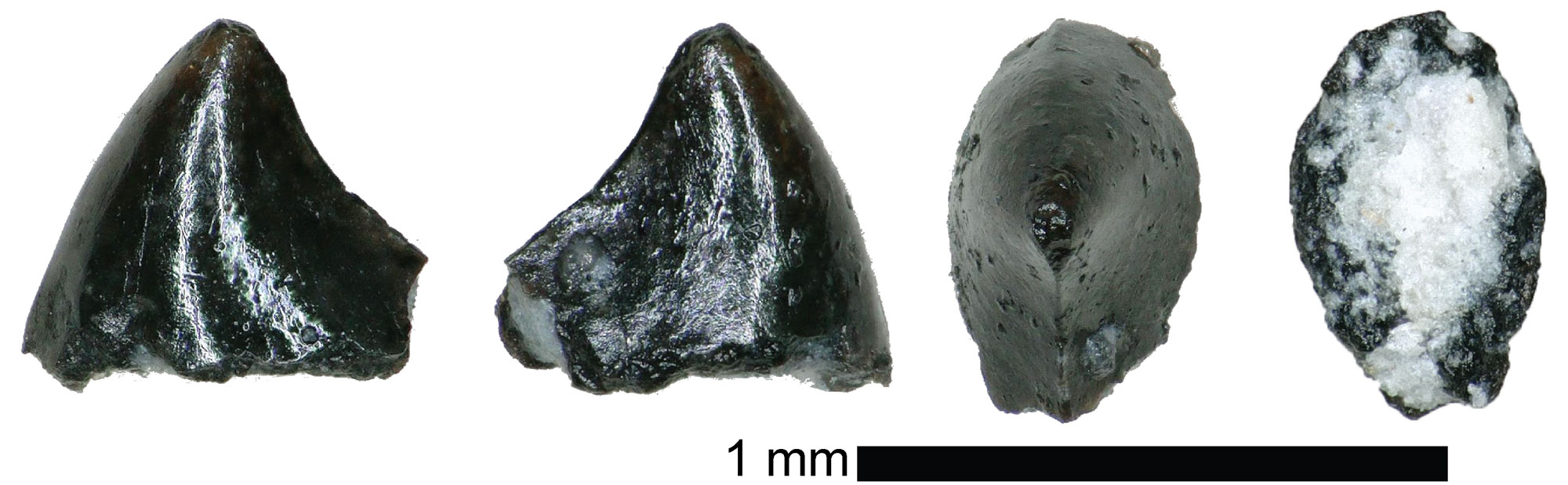

Four views of a marsupial (pouched mammal) tooth from the Late Cretaceous Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation, about 98 million years old. Specimen on display at the Utah State University Eastern Prehistoric Museum (Price, Utah). Source: Fig. 14D, E, F, G from Avrahami et al. (2018) PeerJ 6: e5883 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped, resized, and labels modified).

Late Cretaceous fossils

Late Cretaceous terrestrial animals

Late Cretaceous rocks are widely exposed across southern Utah, and contain a great abundance and diversity of dinosaurs. Late Cretaceous dinosaurs are also known form northern New Mexico. Herbivores are represented by hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), ankylosaurs (armored dinosaurs), and several kinds of ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs).

Theropods (three-toed, carnivorous dinosaurs) are well represented in the southern Colorado Plateau. In the Late Cretaceous, most large teeth and bones found in the region were originally thought to be from close relatives of Tyrannosaurus rex, such as the Albertosaurus, which are well known farther north in Wyoming and Montana. In 2010, however, some of these fossils were identified as a new genus of theropod named Bistahieversor. This predator is estimated to have been around 9 meters (30 feet) long, weighing at least a ton.

The titanosaur (a type of large sauropod, or long-necked, herbivorous dinosaur) Alamosaurus sanjaunensis is known from the Late Cretaceous of New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. A large vertebra (part of the backbone) of this dinosaur that was discovered in the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico in 2004 led researchers to conclude that it may be the largest dinosaur yet found in North America and nearly the largest known worldwide. (You can see a picture of an Alamosaurus skeleton from a display at the Perot Museum on the Earth Science of the South-central United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range page.)

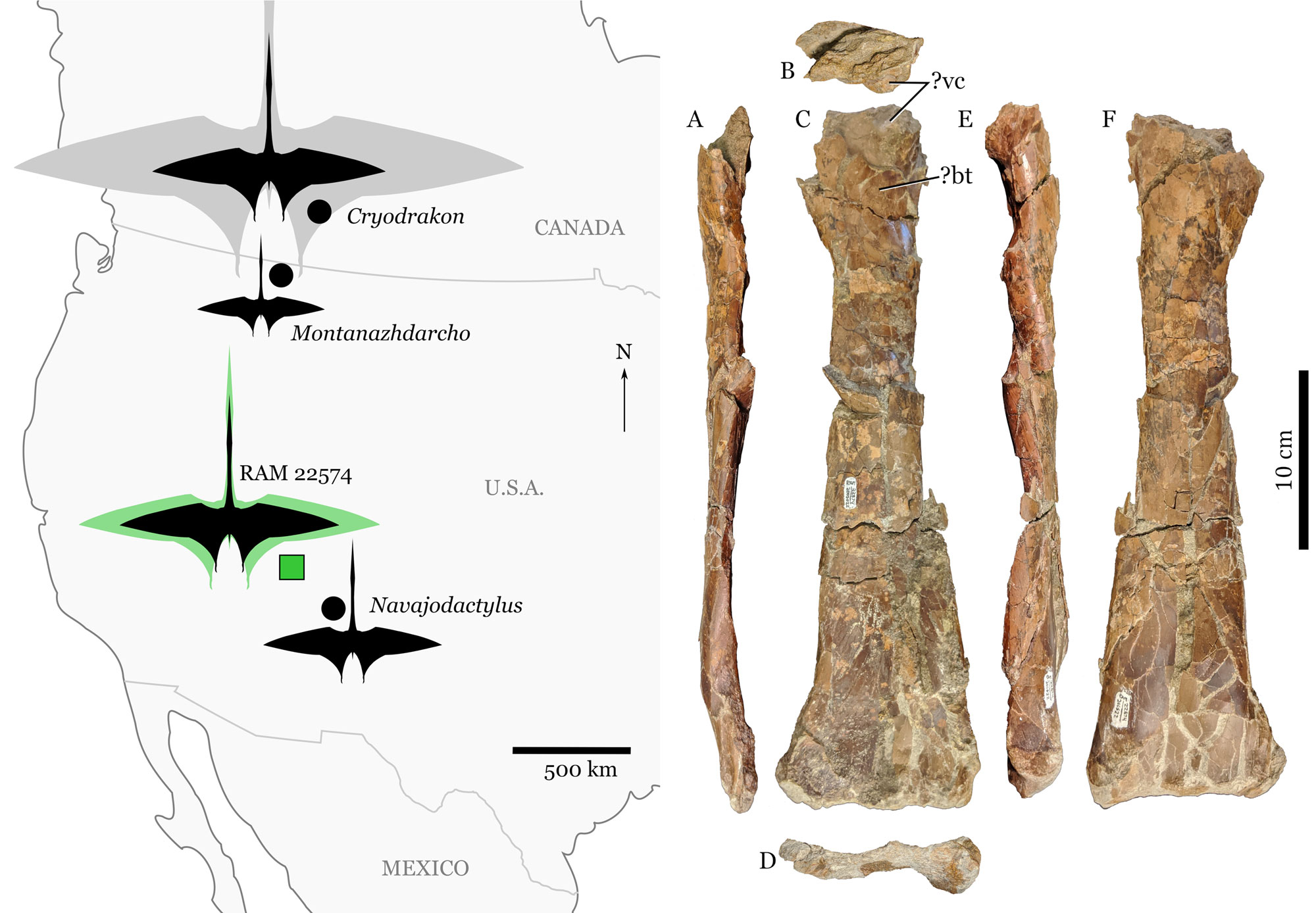

Pterosaurs, including Navajodactylus, have been found in New Mexico and Utah. Fossils of mammals—mostly very small teeth—are also found in the Cretaceous rocks of southern Utah. These fossils represent marsupials (pouched mammals, like koalas and kangaroos), placentals (placental mammals, which include most living mammals), and several extinct groups that left no modern descendants.

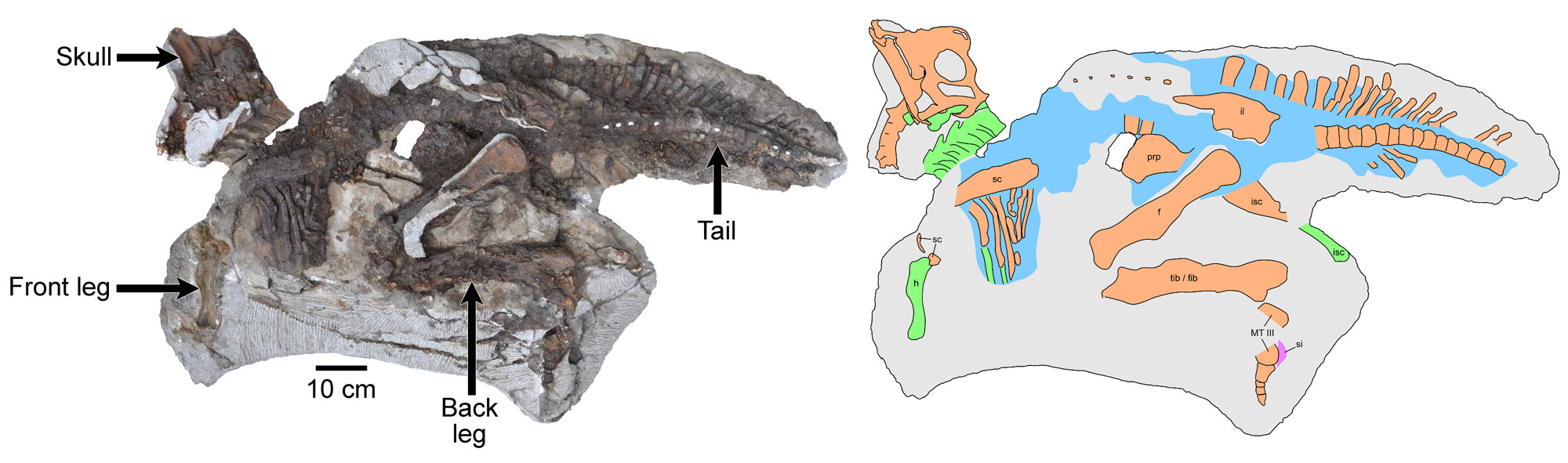

A juvenile Parasaurolophus (a type of duck-billed dinosaur) from the Late Cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Left: Whole specimen. Right: Drawing of the same specimens with bones (orange), bone impressions (green), weathered bone (blue), and a skin impression (pink) color-coded. The letters indicate the names of the bones. Illustrations from figure 3 in A. A. Farke et al. (2014) Peer J 1: e182 (Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped, reconfigured, and labeled).

Akainacephalus johnsoni, an ankylosaur, from the Late Cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Left: Reconstructed skeleton on display at the Utah Museum of National History. Photo by Keratopusuyuuta (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized). Right: Top and side views of the reconstructed skeletons; shaded bones are those that were discovered. Illustrations from figure 28 in J. P. Wiersma and R. B. Irmis (2018) Peer J 6: e5016 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and reconfigured).

Titanoceratops ouranos, a ceratopsian (horned dinosaur) from the Late Cretaceous Fruitland or Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Left: Skeleton (partially reconstructed) on display at the Sam Noble Museum in Norman, Oklahoma. This specimen holds the Guinness World Record for largest land animal skull, granted in 2013. Photo by Kurt McKee (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized). Right: Reconstruction of living animal by LadyofHats (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Skull of Bistahieversor sealeyi, Late Cretaceous Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. On display at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo by Lee Ruk (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Left: Map showing similarly-aged pterosaur discoveries from the Late Cretaceous of the western United States and Canada. In the southwest, Navajodactylus is from the Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. The unnamed animal labeled RAM 22574 is from the Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Right: Views of each side of a pterosaur bone, possibly an ulna (forearm bone), from the Kaiparowits Formation, Utah. Images from Figures 1 and 2 in A. A. Farke (2021) PeerJ 9: e01766 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, images cropped and resized).

Late Cretaceous terrestrial plants

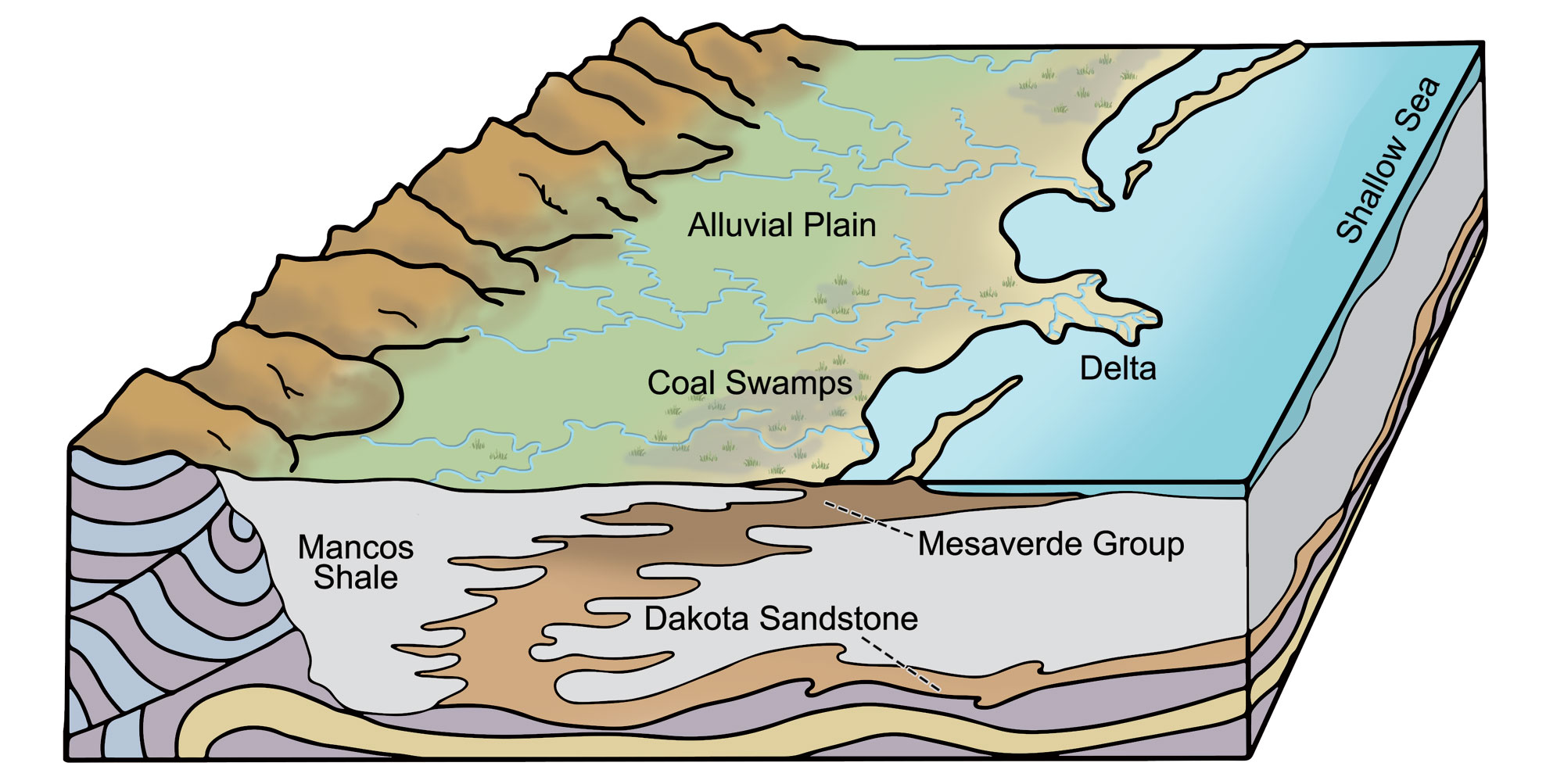

Cretaceous plant fossils are abundant in Utah, especially in Emery and Carbon counties, where large quantities of land plants accumulated in coastal swamps and eventually formed significant deposits of coal. In addition to conifers and tree ferns, which were major contributors to these coal deposits, the region’s Cretaceous land plants include angiosperms (flowering plants) such as palms and magnolias. Currently, fossil evidence suggests that angiosperms originated in the earliest Cretaceous and had diversified and taken over many terrestrial ecosystems by the mid-Cretaceous.

Late Cretaceous plants from the Ferron Sandstone Member (Mancos Shale), Utah. Left to right: A) A conifer shoot (Elatides curvifolia). B) An angiosperm (flowering plant) leaf. C) A conifer shoot (Elatides curvifolia), same specimen as shown in A. D) Fern pinnule (leaf segment). Scale bars = 5 mm (A, B, C), 3 mm (D). Photos by N.A. Jud, from Fig. 3 in Jud et al. (2018) Science Advances 4: eaar8568 (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license, image reconfigured, Figs. A and B resized).

Fossil plants, Late Cretaceous Fruitland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Left: A petrified stump. Right: Sabalites, a palm leaf. Left image and right image by NickLongrich (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, images cropped and resized).

Late Cretaceous marine fossils

As the Western Interior Seaway flooded North America during the Late Cretaceous, portions of the Colorado Plateau were submerged and covered in a series of marine layers. These rocks frequently contain abundant vertebrate and invertebrate fossils. Marine vertebrates include bony fish, sharks, ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs, while invertebrates encompass a great diversity of mollusks, barnacles, and echinoderms.

Relatives of living oysters were diverse and abundant during the Cretaceous; they could cement themselves to surfaces and varied widely in shape and ornamentation. Inoceramus was a large, flat bivalve that could reach diameters of up to 1.2 meters (4 feet)! These mollusks were also important hard substrates for other organisms to attach to in soft sea-floor sediments.

Shells and internal molds of the oyster Inoceramus, Cretaceous Cliffhouse Sandstone, Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico. Photo source: National Park Service (public domain).

The Late Cretaceous Mancos Shale preserves the abundant remains of marine snails, sharks, mosasaurs, crinoids, bivalves, and ammonoids. The Dakota Group includes abundant ammonites and bivalves, as well as the last known North American lungfish from just east of Arches National Park in southeastern Utah. The Tropic Shale and its equivalents are some of the most fossil-rich marine units in North America; ammonoids found here include especially valuable index fossils such as Sciponoceras and Collignoniceras.

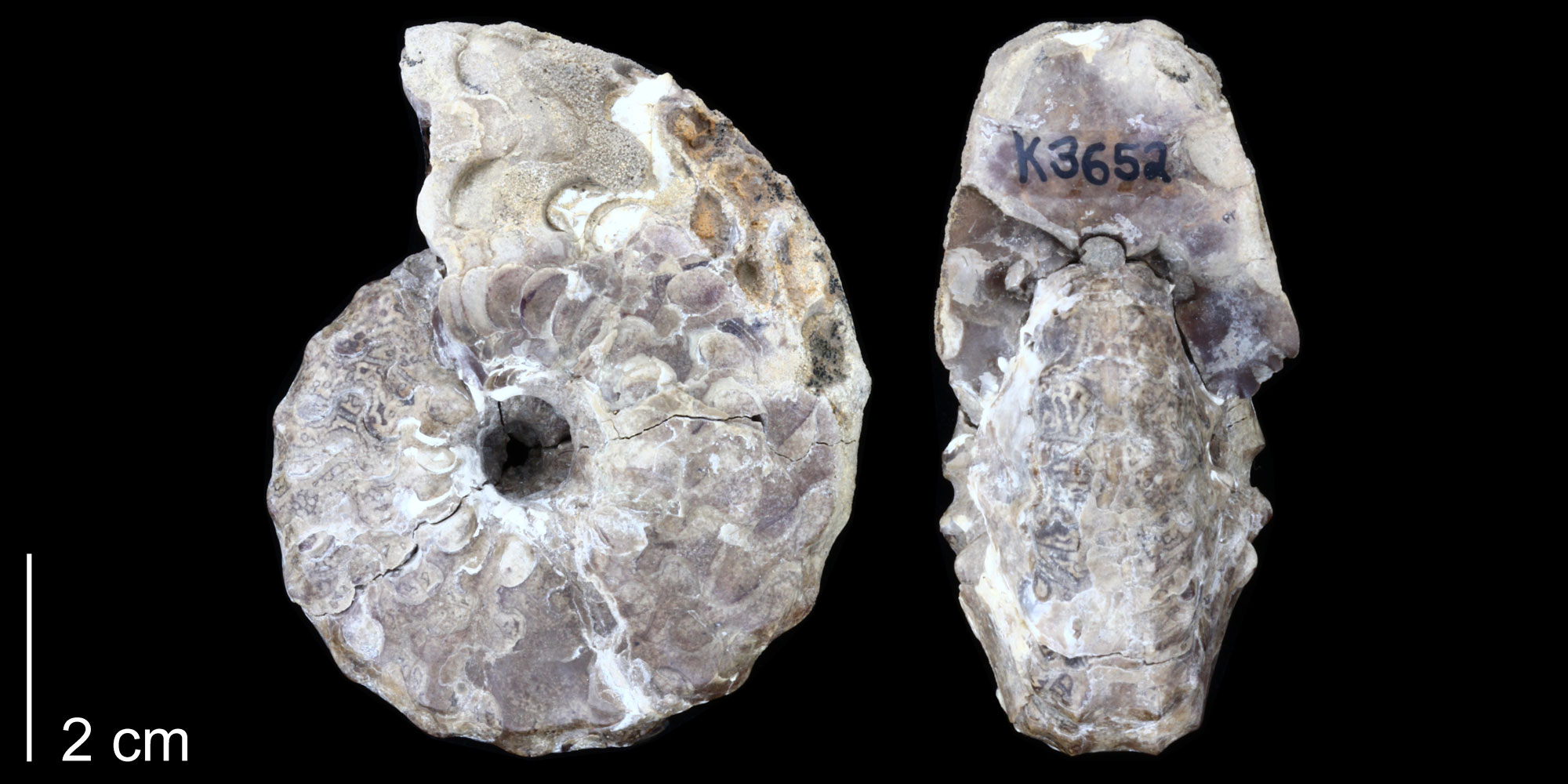

An ammonite (Spathites puercoensis), Late Cretaceous (likely Mancos Shale), Sandoval County, New Mexico. Photo of specimen PRI 70328 (Paleontological Research Institution, via Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

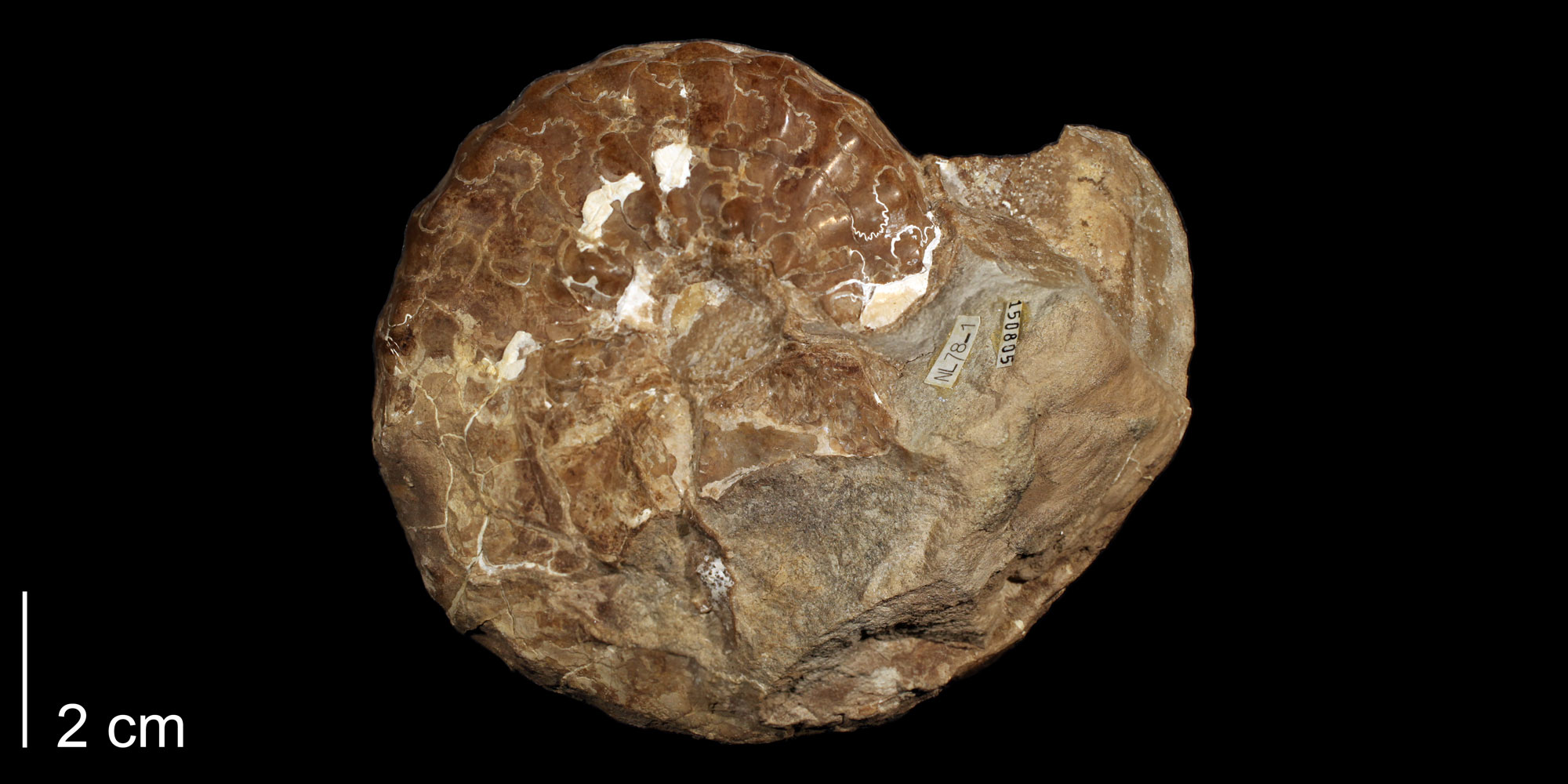

An ammonite (Metoicoceras swallovi), Late Cretaceous Semilla Sandstone Member, Mancos Shale, Sandoval County, New Mexico. Photo of specimen KUMIP 150805 (University of Kansas Natural History Museum, via Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Cenozoic fossils

Paleogene

Paleocene

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary is visible in several areas of the Southwest, especially in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico. This boundary marks the mass extinction that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs, flying reptiles, swimming reptiles, and many other forms of life across the globe.

Rocks above the K-Pg boundary in the San Juan Basin are rich in fossil land mammals. These include a number of major groups, many of which became extinct within a few million years. Multituberculates were a group of mostly small, rodent-like mammals that originated in the Cretaceous and disappeared in the early Oligocene. The name “multituberculate” refers to their distinctive multi-cusped teeth.

Other mammals abundantly represented by fossils in the San Juan Basin are commonly referred to as "archaic," meaning that their features are primitive compared to those of later mammals. These archaic mammals include condylarths, an informal term for a number of early mammals that are not closely related to each other. Some of the earliest known primates were also present at this time. Cenozoic rocks in the San Juan Basin also contain abundant flowering plants.

Taeniolabis, a multituberculate mammal, Paleocene Nacimiento Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Left: Lower jaw with characteristic teeth. Photo of USNM PAL 372278 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain). Right: Reconstruction of Taeniolabis taoensis by Nobu Tamura (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

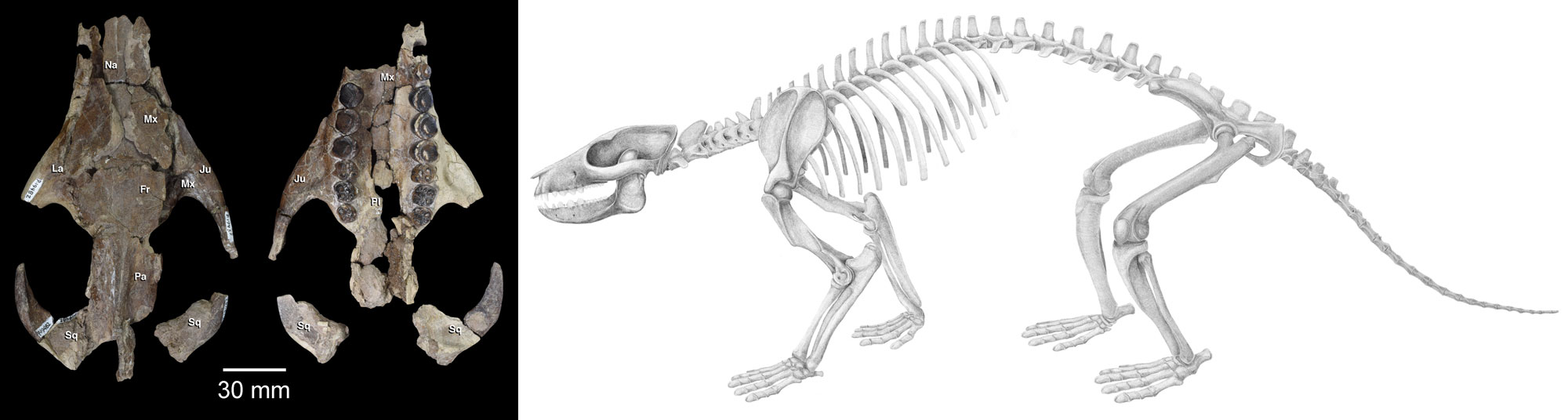

Periptychus carinidens, an archaic condylarth mammal from the Paleocene Nacimiento Formation, New Mexico. Left: Upper part of skull shown from above and below. Right: Reconstruction of complete skeleton. Source: Figures 3B, C and Figure 47 from Shelley et al. (2018) PLoS ONE 13(7): e0200132 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, images cropped, resized, and labels changed).

Wortmania otariidens, a eutherian mammal from the Paleocene Nacimiento Formation, New Mexico. Left: Skull. Right: Reconstruction of the living animal by Matt Celeskey (2012). Source: Figures 1A and 15 from T. E. Williamson and S. L. Brusette (2013) PLoS ONE 8(9): e75886 (Creative Commons Attribution license, images cropped, resized, and relabeled).

Eocene

Uinta Formation

The Uinta Formation, exposed in the Uinta Mountains of northeastern Utah (about 42–45 million years old), is famous for its middle Eocene mammals, including marsupials, insectivores, primates, rabbits, rodents, hoofed mammals, condylarths, and primitive carnivores known as creodonts.

Skull of a fossil alligatorid (Procaimanoidea utahensis), Eocene Uinta Formation, Uintah County, Utah. Photo of USNM V 15996_1 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Protoreodon, an artiodactyl (even-toed hoofed mammal) from the Eocene Uinta Foramtion, Uintah County, Utah. Specimen on display at the Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum, Vernal, Utah. Photo by J. R. Hendricks and E. J. Hermsen.

Pseudodiplacodon progressum, an titanothere from the Eocene Uinta Foramtion, Uintah County, Utah. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Green River Formation

The Eocene Green River Formation is made up of thick layers of brown to cream-colored shale 600–2000 meters (1970–6560 feet) thick, with occasional layers of chert, limestone, and evaporites. It outcrops across a large area of southwest Wyoming, northwestern Colorado, and northeastern Utah. The Green River comprises the largest known accumulation of lacustrine sedimentary rock in the world.

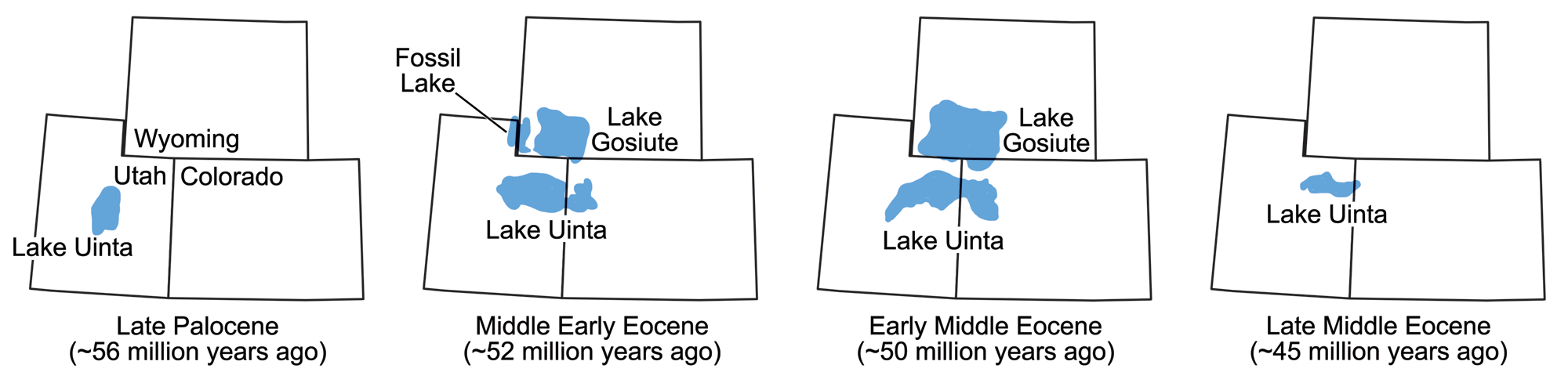

The sediments of the Green River Formation accumulated in a system of large lakes during the Eocene, between 58 and 40 million years ago. In Colorado and Utah, sediments of the Eocene Green River Formation accumulated in ancient Lake Uinta and are preserved in the Piceance and Uinta Basins. A second lake, called Fossil Lake, occurred on the border of northeastern Utah and southwestern Wyoming; its sediments are preserved in the region of Fossil Butte National Monument in Wyoming. Sediments of a third lake, Lake Gosiute, are preserved in the Green River Basin in Wyoming. The Green River Formation lakes existed for differing amounts of time, with Fossil Lake existing for the shortest time and Lake Uinta the longest.

The Green River Formation is famous for the great number of well-preserved fossils found in its lake sediments, especially aquatic organisms, including numerous fish. Many terrestrial animals are also preserved, including insects, birds, and mammals. Green River plants include horsetails, water ferns, terrestrial ferns, conifers, and angiosperms. Green River Formation specimens are on display at many museums in the United States.

The size and location of various lakes in which the Green River Formation sediments were deposited during the Eocene epoch. Maps modified from maps by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, after figure 3 in L. Grande (2013) The Lost World of Fossil Lake.

Fossil cricket (Eogryllus unicolor), Eocene Green River Formation, Colorado. Photo of USNM PAL 577500 image 05, Smithsonian's Paleo-Entomology Lab, Liz Bruce (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

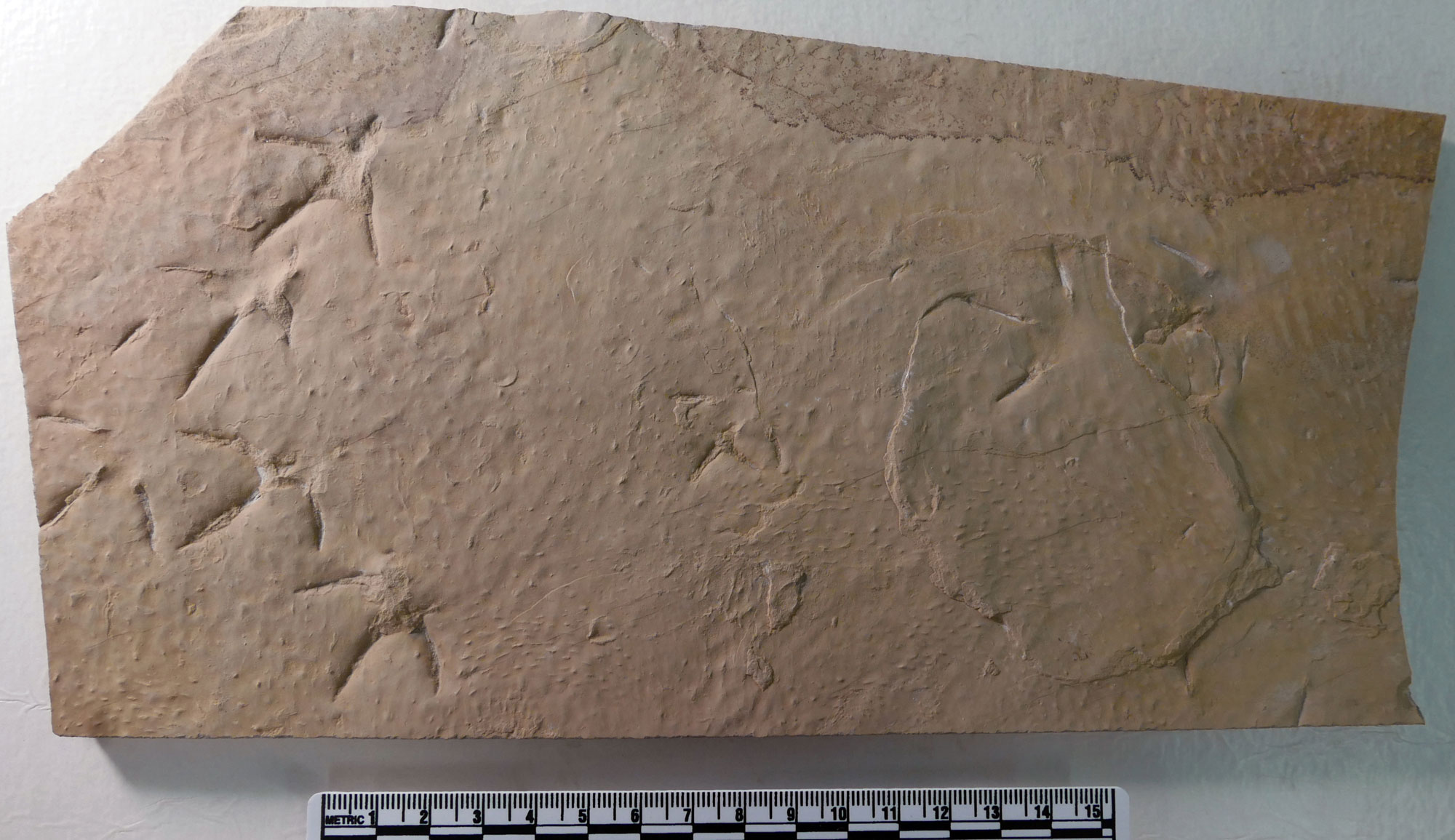

Bird tracks, Eocene Green River Formation, Utah. Photo of USNM PAL 276765 by Mark Florence (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Eocene Green River Formation (Parachute Creek Member) plant fossils at display at the Utah State Field House of Natural History in Vernal, Utah. Left: Wall of plant fossils. Right: Specimen of Macginitea, an extinct relative of the modern sycamore (Platanus). Photos by Jonathan R. Hendricks (2014).

Quaternary fossils

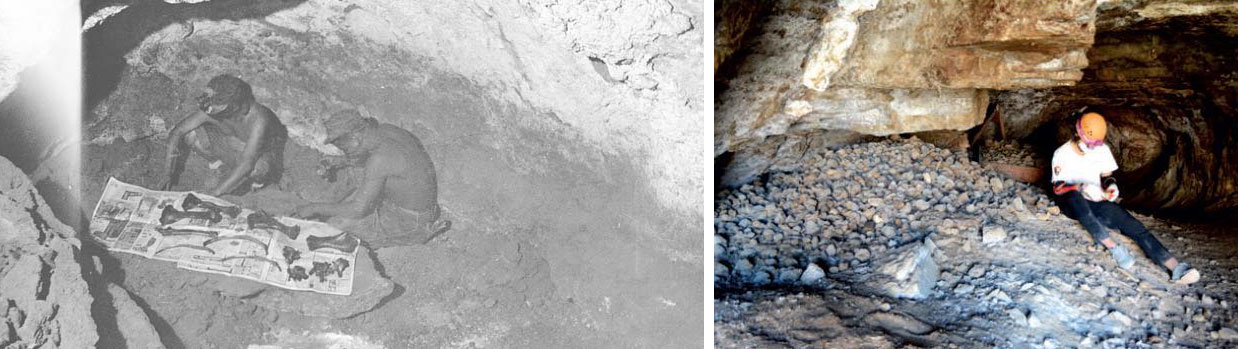

Between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago during the Pleistocene epoch, the Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotherium shastense) inhabited Rampart Cave in the Grand Canyon. Dung samples from this and other caves are rich in well-preserved pollen and other plant material, which allows the diet of these extinct animals to be reconstructed. The preserved dung also contains sloth DNA. Like many other species of large mammals, these sloths became extinct abruptly at the end of the Pleistocene, probably due at least in part to human hunting.

Until 1976, Rampart Cave contained the thickest and least disturbed deposit of stratified Shasta ground sloth dung known to science. While the dung was partially excavated, much of the remaining deposit was destroyed by a human-caused fire in the 1970s.

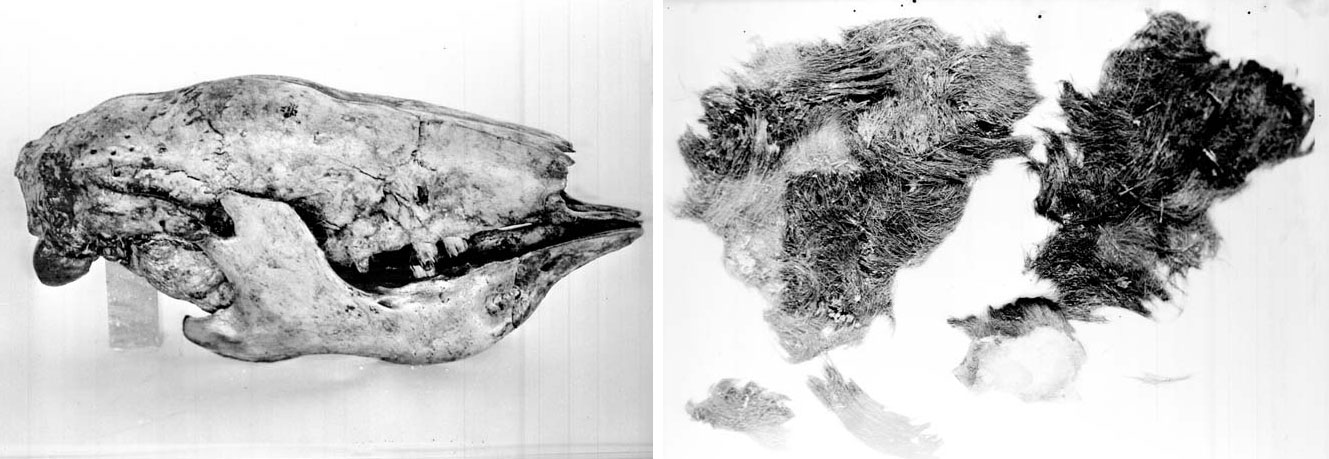

Fossils of giant ground sloths (Nothrotherium) from Rampart Cave, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 1936. Left: Fossil skull. Photo source: Grand Canyon National Park (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped). Right: Fossil hide and hair. Photo source: Grand Canyon National Park (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Cave excavations, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Left: Men collecting ground sloth bones, Rampart Cave, 1936. Photo source: Grand Canyon National Park (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped). Right: Fossil dung in a cave; the dung is estimated to be 20,000 years old. Photo by Robyn Henderek (National Park Service, public domain).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/