Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Columbia Plateau region of the western United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Western US" by Judith T. Parrish, Alexandra Moore, Louis A. Derry, and Gary Lewis, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated May 11, 2022.

Image above: The Palouse Hills in Washington viewed from Steptoe Butte. Photograph by "CamWow" (Wikimedia Commons; Attribution 4.0 International license; image cropped and resized).

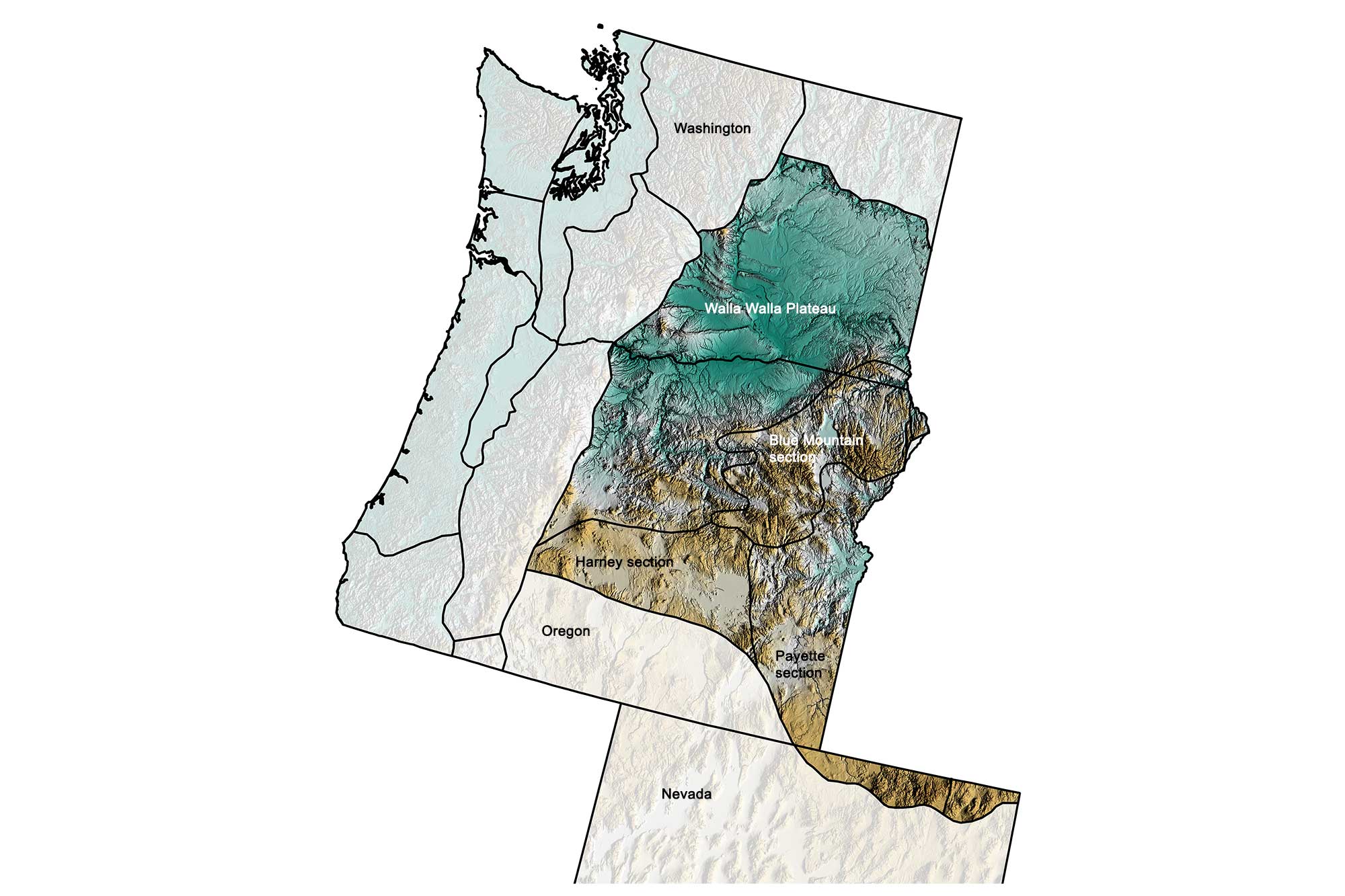

Physiographic subdivisions of the Columbia Plateau of the western United States; greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation, and black lines indicate boundaries of other physiographic regions. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Overview

The interior areas of eastern Washington and central and northeastern Oregon are divided into four major areas: the Blue Mountains, the Harney and Payette sections, and the Walla Walls Plateau.

The Blue Mountains include the Wallowas, which reach a height of 2999 meters (9838 feet). This area is formed of ancient microcontinents, small pieces of continental crust that collided with North America in the Jurassic.

The Wallowa Mountains in Oregon. Photograph by "Linda, Fortuna future" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

The Harney and Payette sections, also called the High Lava Plains, are the result of extensive volcanism during the Neogene. Newberry Volcano, just south of Bend, Oregon, is the westernmost point of eruption for a hot spot that is now responsible for the spectacular volcanic features found in Yellowstone. This hot spot, which has existed for over 16 million years, left its trail across southeastern Oregon and southern Idaho.

Newberry Volcano, Oregon. Photograph by "Tjflex2" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

The Walla Walla Plateau, also called the Columbia Basin, is a broad, volcanic plain composed of basalt. Basalt solidifies from lavas that are very fluid when hot, and the basalt lava in this area erupted along a series of fractures in eastern Oregon, flowing westward. The basalt was so voluminous and fluid that it completely filled the preexisting topography (remnants of which can be seen in hills such as Steptoe Butte and Kamiak Butte in easternmost Washington), forming a broad, flat plain that tilts downward to the west.

Steptoe Butte, a 400-million-year-old quartzite mound protruding from the Columbia Plateau and Palouse Hills in Whitman County, Washington. Elevation: 1101 m (3612 feet). Photograph by Ed Suominen (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

The lava flowed all the way to the Cascades, and even to the ocean, along what is now the Columbia River drainage. In western parts of the plateau, the basalt has been gently folded and faulted by mountain building associated with the uplift of the Cascade Mountains.

The youngest topographic features in the Northern Interior of Washington formed during the most recent ice age when glacial outwash and loess was deposited and later cut by the Missoula Floods, which also carved the Grand Coulee (an ancient river bed) and many of the lakes and channels of the central part of the state. In the Palouse area of Washington and Oregon, glacial outwash formed a series of steeply-sloped silt dunes, which are agriculturally important today due to their highly fertile soil (see photograph at top of page).