Credits

Dr. Don Haas. Most of the content of this chapter is derived from Chapter 1 of The Teacher-Friendly Guide to Climate Change, published by the Paleontological Research Institution (2017).

Page first publicly shared on April 14, 2021; last updated April 21, 2021.

Image above: Students at the 2019 Western New York Youth Climate Action Summit at Buffalo State College. Photo by Kelli Grabowski (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Weather tells you what clothes to wear and climate tells you what clothes to own.¹ In most places, a look out the window can provide good insights into the local climate. Weather is the face of climate. Look out the nearest window to look it in the eye. How has the climate shaped what you see? What do the plant life, the types of buildings, the weather right now, the vehicles that you see, and the clothes people wear indicate about the climate?

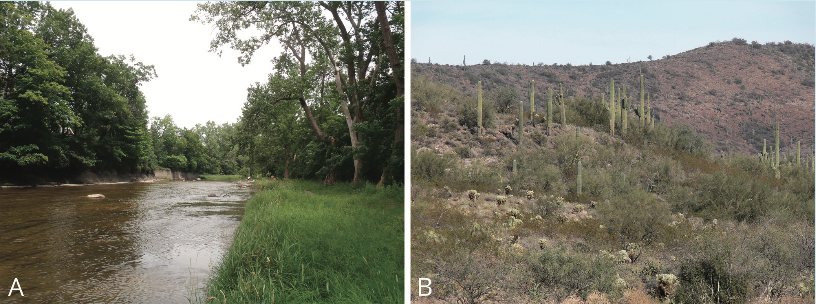

Climate’s fingerprints likely cover much of the view out your window. Animals, plants, people, and infrastructure are all adapted to the climate. Anytime of year, the area around Buffalo, New York looks very different from the area around Phoenix, Arizona. It doesn’t need to be a winter day to be able to tell that a place probably gets below freezing in the winter. Even if it’s raining, you might be able to identify a place that doesn’t get much rain. What are climate’s telltale signs?

(A) Deciduous forest (near Buffalo, NY). (B) A desert setting (near Phoenix, AZ). What visual clues tell you these places differ in their climates, even though the weather on the days these photographs were taken may have been fairly similar? Photographs by Don Haas for PRI's Earth@Home project (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

The Earth’s climate is changing, and the changes are primarily the result of human activities. Climate change² is a real and serious problem for our environment and for humanity, and we can take actions that will make the problems less serious.

These issues, which are expected to influence the lives of all of us for decades to come, make climate change an important topic for discussion, yet most Americans only rarely talk about climate change.³ Talking about climate change is the most important action we can take right now. All of us must become climate change educators. Unfortunately, some of our natural impulses in discussions of important issues are counterproductive. The climate resources within Earth@Home are designed to help anyone deepen their understandings of climate, and to help everyone to have productive discussions about climate.

Your starting point in planning to talk about climate change depends upon a mixture of very local and personal factors. Questions to ask yourself as you move forward include:

- What do I know about climate?

- What do the people I’m talking with know about climate?

- What relevant misconceptions do they and I hold?

- How has climate shaped my community, my region, my country, and the world?

- How is climate change likely to affect things in the coming decades?

- How do I navigate the interconnected scientific, political, economic, and psychological factors connected to this incredibly complex problem?

- What are the most important facts and ideas for all of us to know and understand about climate change?

This virtual book will help you begin to answer these questions. Some of the questions, however, are richly complex and areas of ongoing research and affected by ongoing societal change, and thus will involve a lifetime of learning.

1. Why Talking About Climate Change Matters

“We basically have three choices: mitigation, adaptation, or suffering. We’re going to do some of each. The question is what the mix is going to be. The more mitigation we do, the less adaptation will be required and the less suffering there will be.”

- John Holdren, 2007

John Holdren was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science when he made these remarks. His summation of the problem of climate change concisely describes the choices we face and does so without the level of pessimism sometimes included in such pronouncements. When it comes to climate change there is reason for pessimism, but there is also reason for hope. And for courage. We have the capacity to act, and many of the actions we might take have benefits beyond climate. They also have the potential to save money in both the short and long term and to improve health and other measures of quality of life.

Scientific study of the size and age of the universe, and of the geological and fossil record on Earth, have helped us to understand that humanity is a blip in time on a speck in space.⁴

View of Earth from outside the Solar System, at a distance of about 6 billion kilometers, from the Voyager 1 spacecraft. The image was taken at the request of astronomer and educator Carl Sagan. Image by NASA (public domain).

Because everyone we know and love is encapsulated in this blip and speck, we treasure it deeply and want to preserve its richness, its diversity, and its life-supporting aspects. We are profoundly lucky to live right here and right now. We have a duty to preserve our luck for future generations. This does not speak to the absence or presence of forces beyond nature, but it does speak to the awesomeness and wonder of nature. Understanding the science of Earth systems may deepen our sense of wonder and of our responsibility for sharing it forward.

We are all educators. We educators are lucky to do what we do.

2. Science Learning, Its Application, and Politics

Effective and up-to-date communication about the science of climate change is of paramount importance to good science education, but simply sharing scientifically accurate content is not the same as good teaching. Nor is it all that is required for having effective discussions about climate change. Facts alone are not sufficient to build meaningful understandings. Science does make clear that the biggest challenges we will face in the coming decades will be related to climate, energy, water, and soil, which are inextricably linked with each other.⁵ Society depends upon a fairly stable climate, clean water, energy to power our way of life, and soil to provide the food we need.⁶

Earth@Home addresses the science of climate change, how to talk and teach about it, and about climate change’s interdisciplinary nature. And much more than that. All readers are also well aware that climate change is a deeply socially and politically contentious issue, thus effective climate change teaching and learning also requires understandings of how people decide what is true and worth acting on. This means we must delve into the fields of sociology and psychology, to come to a deeper understanding of how people think, why they think the way they do, and how to consider our own influences and biases.

There is an important philosophical distinction between educating about the science of climate change, and educating about the sorts of actions people can take to mitigate or adapt to climate change. The latter, in focusing on personal actions, may be perceived as encroaching upon political advocacy.⁷ Effective science education and communication, however, should be relevant to peoples’ lives, and climate change is a defining aspect of our current world. No matter what their political leaning, people will need to make lifestyle choices, make sense of the news, and vote; a scientifically literate citizenry will make better, more informed choices about science issues.

Public school teachers and others who teach and talk about climate change must, of course, be careful in regards to advocacy. Effective discourse and learning requires that students consider the classroom a safe place where their (and their families’) world views will be engaged respectfully. Working with other teachers may permit, however, exploring change from different social and economic perspectives. For example, students might explore how the implications of climate change will vary among professions (farmers, insurance brokers, military strategists, social workers, environmentalists, investors, or bankers), regions of the US, demographic setting (urban versus rural), and so on.

And we must communicate to those we talk with that climate change is politically but not scientifically controversial. More than 97% of climate scientists agree that climate change is caused by human activity. Many in the general public believe scientists are divided, and that science teaching ought to address this (perceived) divide. There is uncertainty and disagreement about many of the finer details of climate change, but the idea that human-induced climate change is a real and serious problem is a clear consensus of very nearly all climate scientists.

3. Considering Advocacy, Politics, and Interdisciplinarity

Climate change can be described in purely scientific terms, and building understanding of the relevant basic science is an essential goal of this text. But if you understand only the physical science of climate change, your understanding is shallow and not very useful. The science of climate change matters, and matters greatly, to all of us. Things that matter are also political.

Many of us have been cautioned not to talk about politics. But, if we are to do anything about climate change, we must first talk about it. That reasonably—necessarily—includes at least some attention to politics.

Consider these three questions:

- Are climate change and energy production important issues?

- Do these issues have implications for very nearly every person on Earth?

- Should politics address important issues?

Politics should deal with important issues. Science should deal with important issues. Often, these are the same issues, and that is most certainly the case with climate change. Climate change is one of the most important issues facing humanity. How could it not be political?

Modern climate change is also driven by our actions and is partially a result of the actions of our ancestors. Our understandings will deepen if they are connected to understandings of human history especially as related to the histories of agriculture, industry, transportation, land use, and energy production and use. All of those topics are better understood in concert with cultural and psychological understandings of human nature. And language, mathematics and the arts are all essential for sharing and building these understandings.⁸

Climate change is a problem with scientific, historical, cultural, political, sociological, and mathematical aspects. Language, arts, and, again, mathematics, are needed to build and share our understandings of it. Talking, teaching, and learning about it is enriched by attending to all of these aspects.

For some suggestions on navigating these conversations, see, “Chapter 10: Obstacles to Addressing Climate Change” in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to Climate Change. For a quick start, see Table 10.1: Rules of thumb for teaching controversial issues in that chapter.

4. We All Have Biases

These pages within Earth@Home also give attention to why many people have a difficult time accepting the scientific consensus behind climate change specifically, and, more generally, why perhaps everyone believes some refutable ideas. There are a wide range of reasons why people believe things that aren’t true due to various kinds of cognitive biases and logical fallacies. Among the most important with respect to climate change are the closely related ideas of “identity-protective cognition” and “motivated reasoning.” These are the unintentional thought practices that help us preserve how we see the world and how we stay in good graces with people who think like we do. We seek to protect our feeling of belonging.⁹

There are obvious advantages to both fitting in with those we affiliate with and to maintaining internal consistency among our ways of thinking (worldview) about our community, the broader world, and ourselves. When new evidence threatens our worldview, we may find clever ways to discount the data to maintain our conceptions. When we cannot create explanations for data that seem to conflict with our views, we may instead compartmentalize our beliefs and thereby hold onto perceptions of the way the world works that are in conflict with one another.

Ultimately, we are likely to trust information from the people with whom we most closely identify. That sometimes includes maintaining views in conflict with ample evidence. Determining the difference between reliable and unreliable information is a struggle that has persisted throughout human history and the amount of misinformation available related to both climate and energy is substantial. Problematic arguments (in climate change and elsewhere) stem from both sincere but incorrect information and explanations, and from intent to misinform; though we may blame people with different worldviews for the latter, the former is likely more common.

It is clear, however, that there is a long history of moneyed interests intentionally misleading people in vast numbers with sophisticated efforts.¹⁰ Responding to intentional falsehoods—lies—likely requires a different kind of response than falsehoods that are believed by the person making the argument.

5. Systems and Scales

To understand climate change deeply requires a systems perspective. You, the climate, and the Earth are all systems of systems. Understanding systems—the connections among individual components—is as important as understanding those components in isolation. Seeing things from a systems perspective requires some understanding of feedback loops, tipping points, the history of the system, and the ability to think across multiple scales.

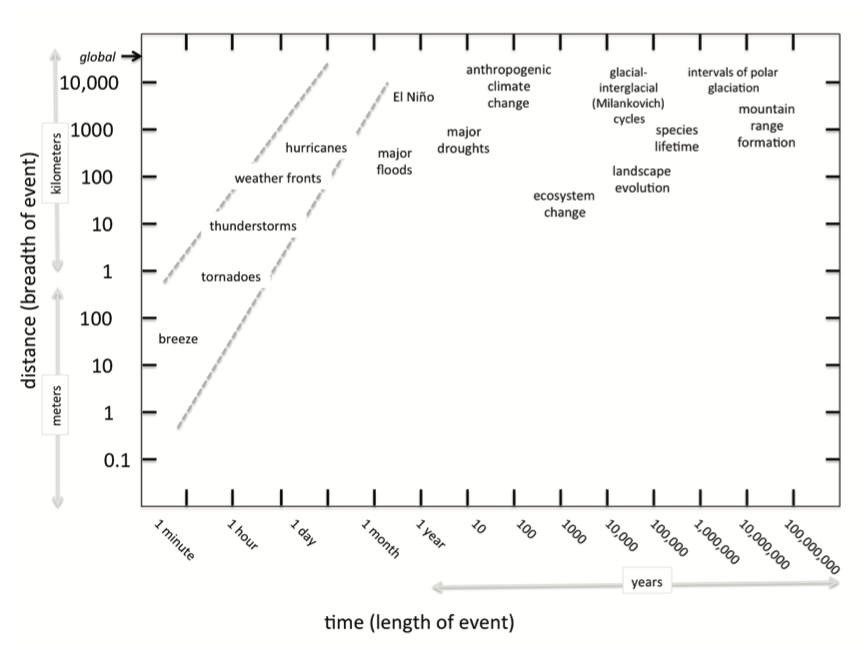

Weather and climate events in time and space, with other Earth system events for comparison, using logarithmic scales. On this plot events in time occur over a span of 15 orders of magnitude and in space over 7 orders of magnitude. Image by Robert Ross for the Earth@Home project (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license), adapted from Figure 8 in Peterson, Garry; Allen, Craig R.; and Holling, C. S., 1998, Ecological Resilience, Biodiversity, and Scale, Ecosystems 1998 1(1): 6–18 (Link).

In terms of decision-making, it includes attention to the notion that advocating against a particular course of action often unintentionally carries advocacy for a course of action not considered.

The abstractions related to understanding very large and very small scales weakens our abilities to make sense of the science and mathematics of climate change and energy. For example, it is cognitively extremely challenging to conceive of and compare large numbers such as a thousand, million, billion, and trillion.

Considering a thousand, a million, a billion and a trillion. In workshops and public programming, we asked participants to mark the correct location of one billion on a line with the end points labeled. “Zero” and “One trillion.” The figure shows a set of typical responses and contrasts that with the reality that one billion is one one-thousandth of one trillion. Images by Don Haas for PRI's Earth@Home project (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Time and space scales smaller and larger than common individual human experiences make it difficult to understand intuitively the importance of atmospheric greenhouse gases and the collective global impact of billions of individuals each influencing the environment in minor ways over decades. We ask our students and the general public to trust the idea that molecules they cannot see are real, that small percentages of the atmospheric composition nonetheless represent billions of trillions of molecules per liter, and that changes in the amount of these molecules over timescales stretching thousands to billions of years have influenced the history of Earth’s climate.

For the overwhelming majority of human history—up until the last several decades—the average person did not have much use for understanding the differences among a thousand, a million, a billion, and a trillion. Now such understandings are important for understanding climate, energy, economics, and a wide range of societal issues. For example, on the typical day in the US, 390 million gallons of gasoline are burned—more than a gallon per person per day. Each of those gallons contains 5.5 pounds of carbon and burning each gallon releases that carbon into the atmosphere. That emits over two billion pounds of carbon into the atmosphere each and every day, just from Americans burning gasoline. But most of us struggle to make meaningful interpretations of those numbers beyond that they are very large and difficult to comprehend.

Because systems and scales are inherently difficult concepts, we must find models and activities to help people past these hurdles. For these reasons and others we will need different approaches to education than traditional didactic and discipline-focused approaches.

6. Love and Beauty Will Persist

Engaging in the important work of climate and energy education can be profoundly depressing. Understanding the environmental challenges we face means confronting challenges that are on a scale perhaps never faced by humanity. Civilization and agriculture arose and came to thrive in a relatively stable climate, and it was the general stability of the climate that allowed the rise of civilizations. The climate is no longer as stable as it was, and is changing in some ways that will be difficult to adapt to and some that are difficult to predict. Teaching and talking about it can also be incredibly meaningful and satisfying.

And though climate is changing, and we will almost certainly lose some wonderful environments, species, and human settlements, we won’t lose it all, and to at least some degree new ones will also emerge. If the efforts get you down, consider, for example, spending time in a natural environment. Many places that we consider of great beauty and value have been impacted by humans, such as in the widespread forests of the Northeastern US. Regrettably, almost none of this forest is original “old growth”—that was lost a few generations ago to humanity’s hunger for fuel, building materials, and other land use. But in certain respects there is more nature in these areas than there was a century ago. And some of the lakes and rivers in the region are much cleaner than they were fifty years ago, as is the air of many cities. These are just a few examples of many stories in which increased scientific awareness, understanding, and change that people worked together to make have made a positive difference.

Aerial photograph taken in 1938 of land near Ithaca, NY and satellite photograph of the same area taken in recent years. This regrowth of forests is typical of many parts of the Northeastern US. Aerial photograph from the Cornell University Library Digital Collections New York Aerial Photographs from 1938. Satellite photograph screenshot from Google Maps, retrieved April 2021.

7. Resources

In the last several years there has been an explosion of high quality resources for fostering effective communication about climate change. What follows is a small sampling of those resources. Resources from The Paleontological Research Institution are listed first with other resources in alphabetical order.

Books

Zabel, Ingrid.H.H., Don Duggan-Haas, Robert M. Ross, and Alexandra Moore, eds. The Teacher-Friendly Guide to Climate Change. Ithaca, NY: Paleontological Research Institution, 2017.

The chapter you are just finishing reading is adapted from Chapter 1: Why Teach Climate Change? from The Teacher-Friendly Guide to Climate Change by Ingrid Zabel, Don Haas, Robert Ross and Alexanda Moore. The award-winning book includes both the basics of climate change science and perspectives on teaching a subject that has become socially and politically polarized. The focus audience is high school Earth science and environmental science teachers, and it is written with an eye toward the kind of information and graphics that a secondary school teacher might need in the classroom. While it is written with teachers in mind, the book is friendly to a broad audience. It is useful for anyone who wants to better understand climate change and how to more productively talk about it. It is the tenth book in the Paleontological Research Institution's Teacher-Friendly Guide series.

Gardiner, L. S. Tales from an Uncertain World: What Other Assorted Disasters Can Teach Us About Climate Change. University of Iowa Press, 2018.

Tales from an Uncertain World: What Other Assorted Disasters Can Teach Us About Climate Change by Lisa Gardiner offers a frank but optimistic discussion of the climate crisis. The author gives encouraging attention to the role of individual action without losing sight of the essential need for broad societal response.

Johnson, Ayana Elizabeth, and Katharine Keeble Wilkinson, eds. All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. First edition. New York: One World, 2020.

All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, edited by by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson, is an anthology of writings by 60 women at the forefront of the climate movement. The poems and essays invite everyone into climate activism. The project that created the book also has a companion website with resources to support reading circles.

Mann, Michael E. The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Change Denial Is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Award-winning climate scientist Michael Mann and Pulitzer-Prize winning cartoonist Tom Toles offer rich insights into the science of climate change and how to communicate it with a sense of humor in The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Change Denial Is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy.

Morrison, Deb, and Tom Bowman. Resetting Our Future: Empowering Climate Action in the United States. John Hunt Publishing, 2021.

The Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) Framework for the United States is our national effort to address Article 6 of the Convention (1992) and Article 12 of the Paris Agreement. This is a treaty obligation in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Empowering Climate Action in the United States (Resetting Our Future) is the US ACE Framework in book form. The book, edited by Tom Bowman and Deb Morrison, lays out the ACE National Strategic Planning Framework for the United States. The Framework is a game changer for climate action that has brought together a diverse set of leaders in climate action and education in an unprecedented effort.

Online Resources

The Paleontological Research Institution's Climate Change & Energy Education Collection includes a wide range of resources, including online and physical museum exhibits, an extensive collection of videos, teaching activities, The Teacher-Friendly Guide to Climate Change, and other online texts including what you are reading right now.

Climate Change Evidence and Causes from The Royal Society and The National Academy of Sciences was originally published in 2014. The content was updated in 2020 and is now available through this interactive web page as well as in pdf format. It provides answers to frequently asked questions about climate change science.

The Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN) is both a collection of peer-reviewed teaching resources and a community of climate and energy educators and educational researchers. The CLEAN Collection includes over 700 resources that have each been reviewed by both a science content expert and a pedagogical expert. The CLEAN Network includes over 600 professionals and activists working on climate and energy education. The Network interacts through an active listserv and weekly webinars.

The Debunking Handbook 2020 is offered through Skeptical Science and carefully lays out strategies to avoid the backfire effect and more generally how to engage with people who disagree with the scientific consensus about human contributions to climate change. This is a substantial update to the original, published in 2011. While the updated version now includes 22 authors, they kept the Handbook concise. The pdf is 19 pages, and it is available in several languages.

The Skeptical Science website offers a wide range of resources to investigate skepticism of climate skepticism.

Additional References:

Kenner, R. (2014). Merchants of Doubt [Documentary]. Sony Pictures Classics. https://www.sonyclassics.com/merchantsofdoubt/

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Ballew, M., Goldberg, M., & Gustafson, A. (2018). Climate change in the American mind: December 2018 (p. 49). Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Climate-Change-American-Mind-December-2018.pdf

Mungai, C. (2019, January 30). Perspective | Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Sagan, C., & Druyan, A. (2011). Pale Blue Dot: A vision of the human future in space. Ballantine books. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9hzqn9gWtAcC&oi=fnd&pg=PR13&dq=Pale+Blue+Dot&ots=KcUudiWg09&sig=JdrwvSSh-tDtlwoLEXHt8DHAWI0

Schlottmann, C. (2014). Ethical issues for education and climate change. In Canned Heat: Ethics and Politics of Global Climate Change (pp. 210–224). Routledge.

State of New Jersey Department of Education. (2020, June 3). New Jersey Student Learning Standards. Adopted 2020 New Jersey Student Learning Standards (NJSLS). https://www.nj.gov/education/cccs/2020/