Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Rocky Mountains region of the southwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Wasatch Mountains; Uinta Mountains; Southern Rocky Mountains; Rio Grande Rift; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Southwestern US" by Bryan L. Isacks, Richard A. Kissel, and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated April 8, 2022.

Image above: The Wasatch Mountains towering above downtown Salt Lake City. Photograph by "Garrett" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

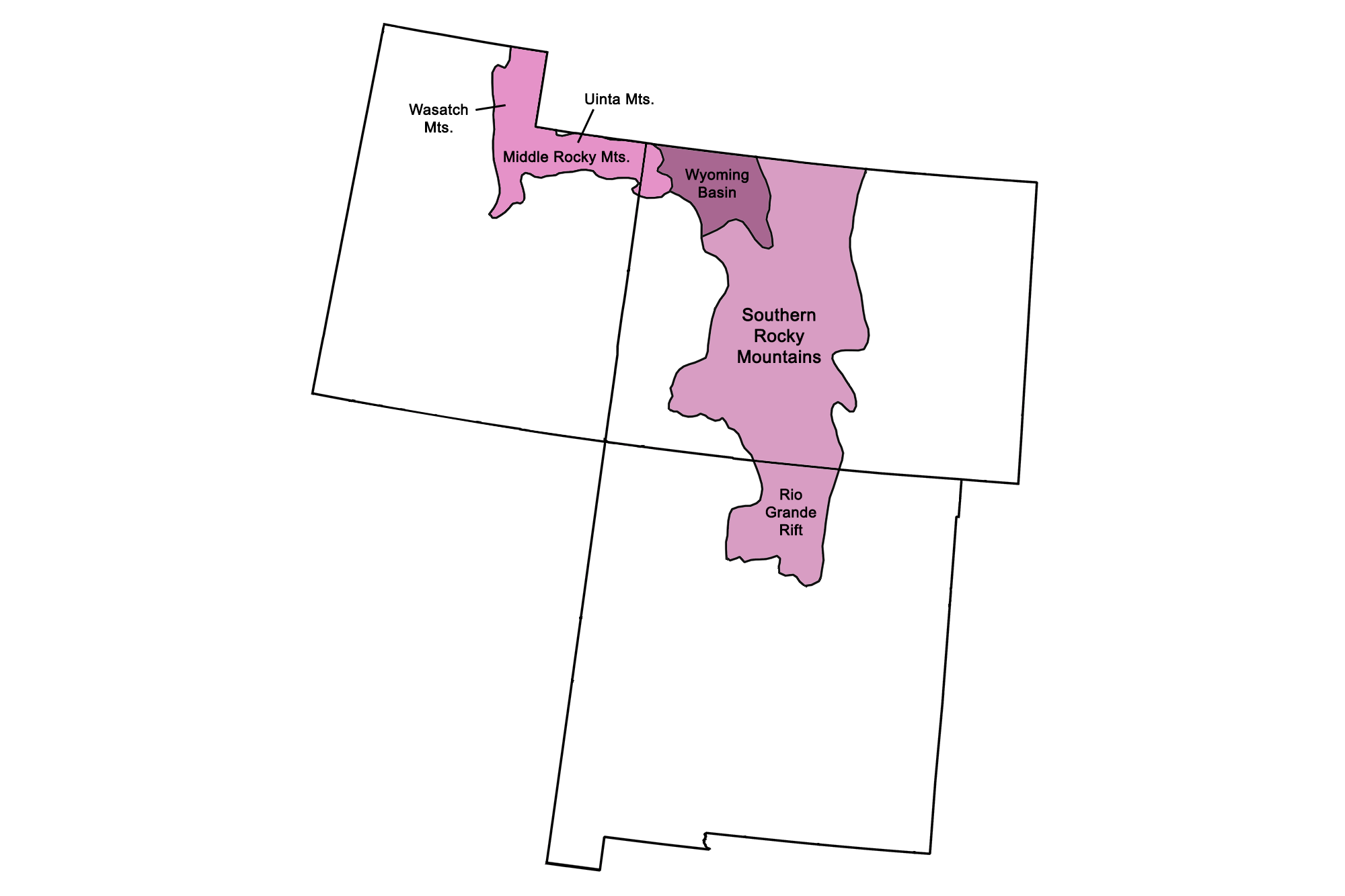

Physiographic subdivisions of the Rocky Mountains region. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Overview

The Rocky Mountains of the Southwest consist of multiple uplifted ranges resulting from the Sevier and Laramide orogenies, as well as from Cenozoic volcanism and extension. The mountains extend more than 4800 kilometers (3000 miles) from northern British Columbia southward through Alberta, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and—in the Southwest—into central and western Colorado, northeastern Utah, and north-central New Mexico.

They include the high and rugged mountain ranges of the Southern Rocky Mountains, located between the Colorado Plateau and the Great Plains; the Uinta Mountains (Middle Rocky Mountains), bordering the northwestern part of the Colorado Plateau; and the Wasatch Mountains (Middle Rocky Mountains), located in Utah along the eastern border of the Basin and Range. Because of their high elevations, all the ranges capture rain and snow, and have been subjected to both fluvial and glacial erosion during the Quaternary. Evidence for this varies from the cirques and U-shaped valleys of the Front Range to the massively glaciated San Juan Mountains and their numerous huge rock glaciers (glaciers buried in talus).

The Rocky Mountains, from the Wyoming border to northern New Mexico, boast 53 peaks over 4200 meters (14,000 feet) high—the "Fourteeners" of mountain climbing fame. The highest part of the Rocky Mountain uplift is centered in Colorado; the state has the highest concentration of mountains over 4200 meters (14,000 feet) high in the continental US, as well as the highest base elevation of any area of the continent. Forty of these peaks are located in Colorado's Sawatch, Sangre de Cristo, and San Juan ranges, and were uplifted by faulting or magmatic activity during the mid- to late Cenozoic.

Wasatch Mountains

The Wasatch Mountains, located at the western edge of the Rockies in between the Basin and Range and the Colorado Plateau, stretch approximately 260 kilometers (160 miles) south from the Utah-Idaho border. This mountain range owes its current high relief mainly to faulting that encroached into the Colorado Plateau during the Cenozoic. Normal faulting is still active along the Wasatch Fault today, posing seismic risks to Salt Lake City.

There are no exposures of Precambrian basement rock in the Wasatch Range, except for a small area near the westward extension of the Uinta uplift—the mountains are largely made up of Paleozoic strata. The mountain range is punctuated by valleys, into which it drops steeply on its western side and more gently to the east. Much of the Wasatch Range exhibits glacially sculpted landforms.

Mount Timpanogos in Utah’s Wasatch Range displays the sculpting power of moving ice. Alpine glaciers shaped the mountain’s knife-edge ridges and its wide U-shaped amphitheaters. Photograph by "a4gpa" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

Uinta Mountains

The Uinta Mountains are the only the only part of the Rockies where the mountains run east-west instead of generally north-south. This range is a classic example of Laramide uplift, when the Precambrian basement rock and its cover of Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary strata were pushed up to form an anticline bounded on either side by low-angle thrust faults. The faults dipped beneath the Precambrian basement and thrust it above sedimentary cover, deforming the strata into basins adjacent to the mountain range. During and subsequent to these crustal deformations, erosion removed the entire series of Paleozoic and Mesozoic strata above the uplift, exposing the more resistant Precambrian rocks beneath. The exposed Precambrian block eroded slowly, forming relatively smooth relief during the Cenozoic, and was nearly buried by the accumulation of eroded sediments. During glaciation in the Quaternary, the highest parts of the Uinta Mountains were covered by an ice field. High peaks poked through the ice as isolated points called "nunataks," while glaciers moving down on either side carved cirques and U-shaped valleys, generating the alpine ruggedness we are familiar with today.

During the mid- to late Cenozoic, the eastern part of the Uinta uplift played a key role in shaping the flow of the Colorado River. In the mid-Cenozoic, the ancestral Green River flowed south from the Wind River Mountains in northern Wyoming and then east towards the Great Plains. After the Laramide Orogeny ended, faulting in the low-elevation and sediment-covered eastern segment of the Uintas led to a complex series of stream captures that eventually connected the southward flow of the Green River to the then-northern headwaters of the Colorado River. With this added contribution of water from the Wind River and Wyoming ranges and the northern slopes of the Uintas, the connection cut through the sedimentary cover to carve the dramatic Lodore Canyon into the Precambrian core of the Uinta uplift.

The Green River flows through the Gates of Lodore near Dinosaur National Monument, Colorado. Photograph by "GreenRiverLodor" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Southern Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains of Colorado and New Mexico have a complex topographical history. Their high relief is a product of four components: uplift of the late Paleozoic Ancestral Rockies, compressional uplift of Precambrian basement rock during the Laramide Orogeny, igneous activity during the mid-to-late Cenozoic, and extensional tectonics associated with the Rio Grande Rift. The effects of volcanism and the Rio Grande Rift were most important at the region's southern end, where the rift dominates the landscape (see below).

The Ancestral Rockies date to the Pennsylvanian, during which time thrust faulting uplifted the Precambrian basement rock in Colorado and northern New Mexico. These ancient mountains were covered beneath the Western Interior Seaway during the Mesozoic, but they generated weaknesses in the crust that led to greater faulting during the Laramide Orogeny. During the late Cretaceous and early Cenozoic, the Rockies were rejuvenated by compressional uplift, and erosion began anew, cutting stream valleys and leaving the more resistant rock as topographic highs. Alpine glaciers later carved cirques into the high peaks, leaving the rugged sharp peaks we see today. This is best exhibited in the northern Colorado Rockies, including the Front Range north of Colorado Springs, the Gore Range near Vail, and the Park Range, which extends north into Wyoming.

The view from Mount Evans, one of the highest points in Colorado’s Front Range at 4350 meters (14,271 feet). (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

In between these ranges lie the North Park and Middle Park basins, which are broad, lower areas of relatively low relief floored by Precambrian basement rocks. Meltwater from glaciers deposited outwash plains and terraces downstream—Rocky Mountain National Park in northern Colorado contains spectacular examples of these features.

Farther south, the Rocky Mountains become increasingly affected by Cenozoic faulting and volcanism associated with the Rio Grande Rift. On the western side of the rift, the Elk, Sawatch, and Mosquito ranges are cut by a rift valley (graben) bordered by normal faults between the Sawatch and Mosquito ranges. The valley forms the headwaters of the West Arkansas River. The Nacimiento Mountains are another example of Laramide-aged basement uplift; their Precambrian rocks thrust towards the west. The northern part of the range includes the San Pedro Parks Wilderness Area, which has the highest elevation of the mountain range, reaching up to approximately 3230 meters (10,600 feet). The area's high relief is due to the resistance of its Precambrian plutonic rocks. The San Juan Mountains, also located on the rift's western side, are primarily mid-Cenozoic volcanoes that are now deeply eroded into rugged mountains. The ruggedness of the terrain, especially in contrast to mountains formed from Precambrian metamorphics, highlights the difference in erodability between the two types of rocks.

East of the rift across the South Park Basin, uplifted Precambrian basement rocks of the Rampart Range and Pikes Peak Massif face the Great Plains. Exposures of uplifted Precambrian rocks continue in the Wet Mountain Range and the long, narrow Sangre de Cristo Range, which ends south of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains were uplifted in the mid- to late Cenozoic through a process similar to Basin and Range extension. South of the Sangre de Cristo Range, the mountains are slightly lower in elevation. The Sierra Blanca Mountains are the eroded remains of a large mid-Cenozoic volcano with peak elevation reaching nearly 3700 meters (12,000 feet). The Sandia Mountains, reaching peak elevations just under 3000 meters (10,000 feet), comprise uplifted late Paleozoic and Mesozoic strata.

Rio Grande Rift

The Rio Grande Rift is a zone of extension that reaches from New Mexico's Basin and Range up through the Rocky Mountains to central Colorado, near Leadville. Recent studies indicate traces of the rift may extend farther north, almost to the Wyoming border. Cenozoic volcanic activity within the rift had a major impact on the topography of the surrounding Rocky Mountains, including the flow of the Rio Grande River. When the rift formed, it captured the river, which initially began as a stream trickling from the mountains near Leadville.

The Jemez Lineament in northern New Mexico is thought to be an elongate, ancient crustal weakness through which magmas erupted as part of the Basin and Range extension. Where the Jemez Lineament crosses the Rio Grande Rift, more intense volcanism occurred, forming the Jemez Volcanic Field. This area includes the Valles Caldera, a supervolcano that last erupted approximately 1.5 and 1.2 million years ago. Its crater measures approximately 19 by 24 kilometers (12 by 15 miles) across; the younger caldera, 22 kilometers (14 miles) wide, partially buried the older. The supervolcano eruptions produced thick tuffs (i.e., the Bandelier Formation), which cover the eastern side of the caldera and form the Pajarito Plateau. The tuffs slope gently eastward, and are eroded into narrow, vertically walled canyons with relief of up to 240 meters (800 feet). Hoodoos, such as those found at the Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in Sandoval County, New Mexico, are also common formations found in Jemez pyroclastic flows.

Hoodoos at Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in New Mexico. Photograph by Kevin O'Mara (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

The northeast trend of late Cenozoic volcanism continues farther across the Rio Grande Rift and into the Great Plains. This linear movement has been attributed to a hot spot track, but the dates of the eruptions do not travel in a line from oldest to youngest, as do those associated with other well-known hot spots such as Yellowstone or Hawai‘i.

The Rio Grande Rift is also occupied by a series of high-altitude basins: the upper Arkansas graben and San Luis Basin in Colorado, and the Espanola, Albuquerque, and Socorro basins in New Mexico. Each basin is filled with sediment eroded from the nearby mountains and interbedded with volcanic ash and lava. The San Luis Valley covers approximately 21,000 square kilometers (8000 square miles) of Colorado and a small portion of New Mexico. One of the valley’s most prominent features is the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, which contains the tallest sand dunes in North America.

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Colorado. Photograph by "Thomson20192" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

The sand in these dunes formed from Cenozoic deposits left by the Rio Grande and its tributaries, which flow through the valley. The dunes rise approximately 230 meters (750 feet) from the valley floor, near the western base of the Sangre de Cristo Range.