Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Basin and Range region of the western United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Western US" by Judith T. Parrish, Alexandra Moore, Louis A. Derry, and Gary Lewis, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated May 11, 2022.

Image above: Westward view from Berlin Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada showing Basin and Range topography: a flat basin in the foreground and a range in the distance. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

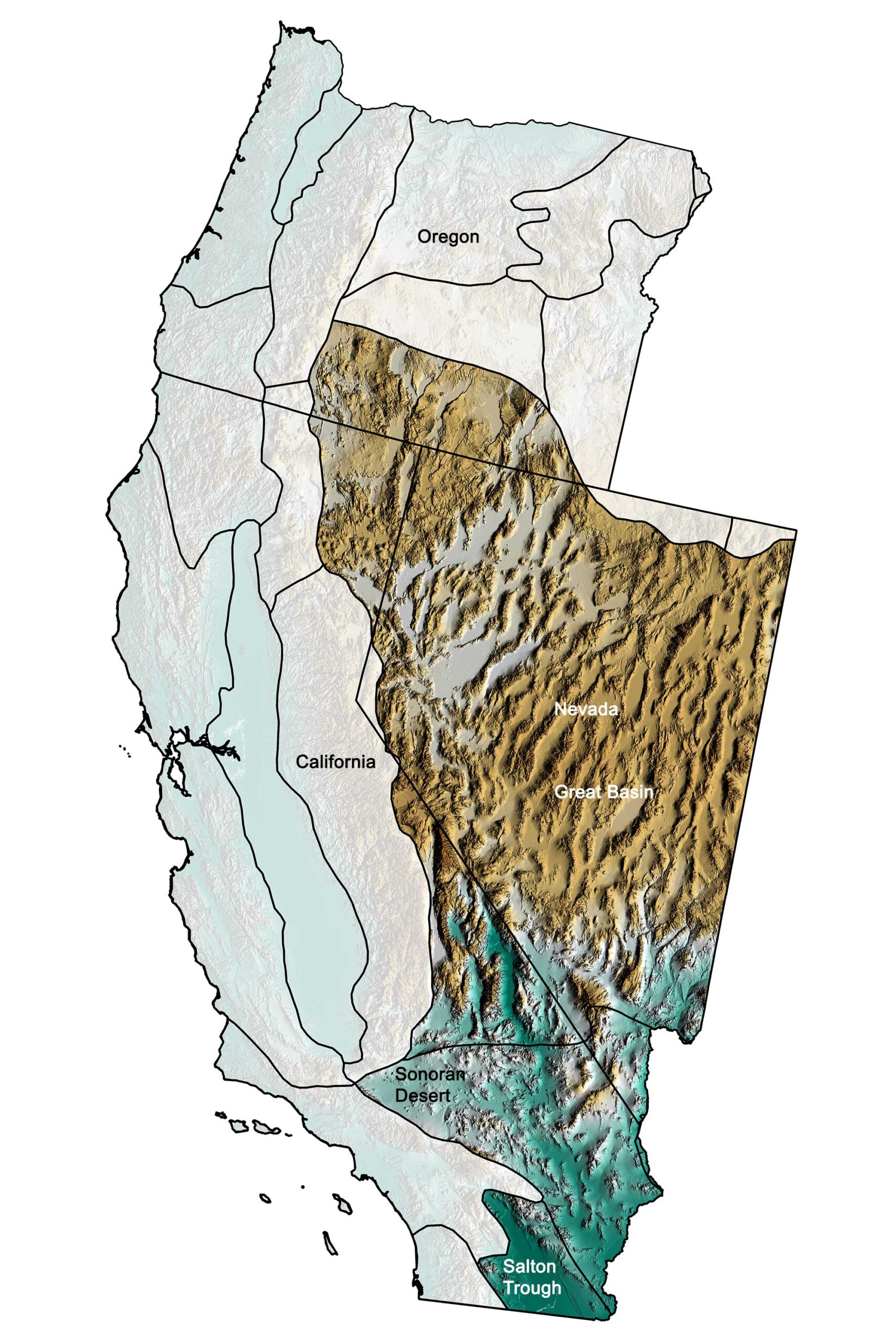

Physiographic subdivisions of the Basin and Range region of the western United States. Greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation; black lines indicate state boundaries or boundaries of other physiographic provinces. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Overview

The Basin and Range possesses perhaps the most unique topography of the Western United States. It covers a large area of the U.S., extending to the Rocky Mountain, Southwestern, and South-Central states. Basin and Range topography is characterized by alternating valleys and mountainous areas, oriented in a north-south, linear direction. The entire region, including all of Nevada, southeastern California, and southeastern Oregon, consists of high mountain ranges (mostly running north-south) alternating with low valleys.

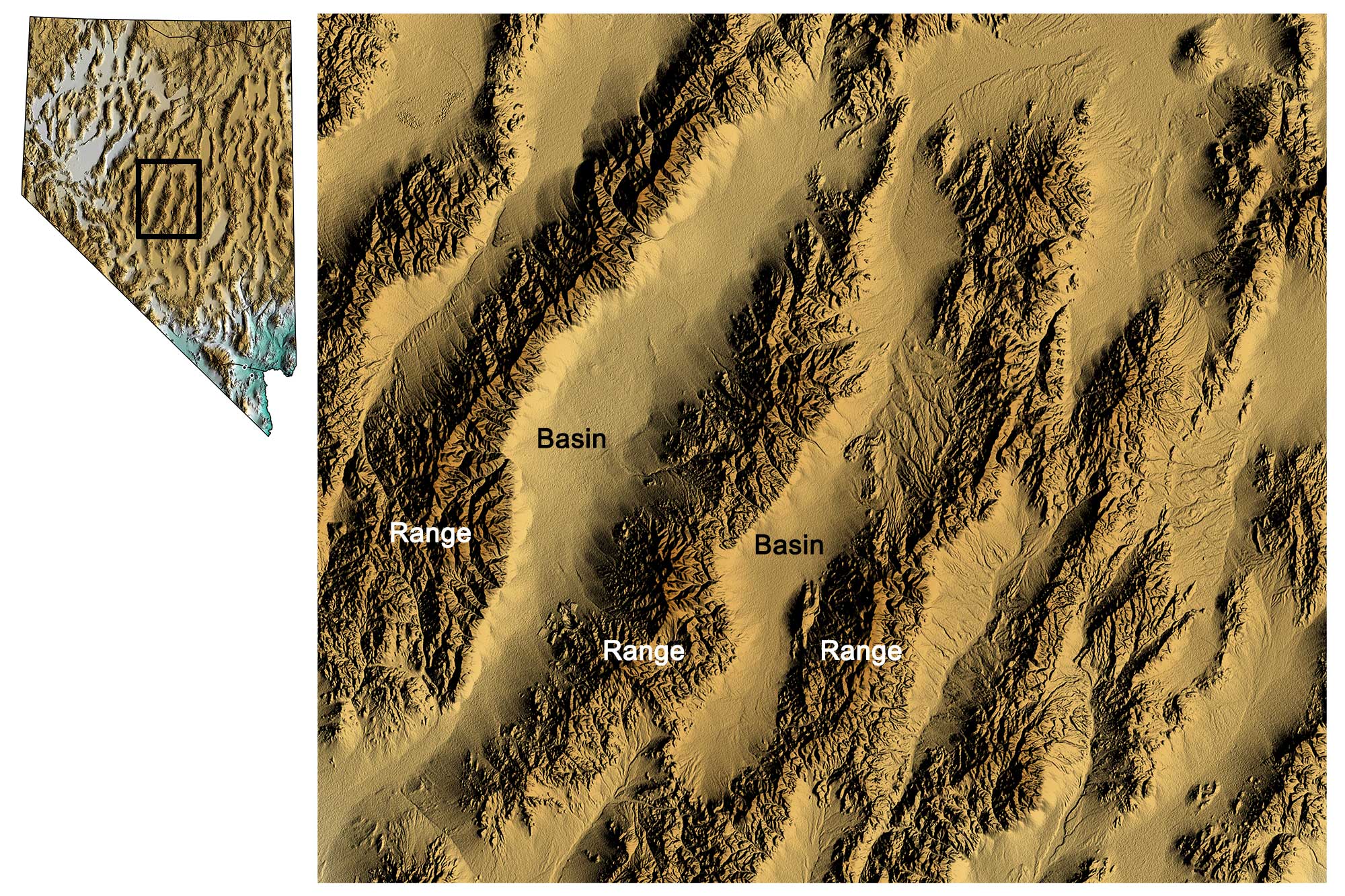

Basin and range topography in central Nevada; darker browns indicate higher elevation. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

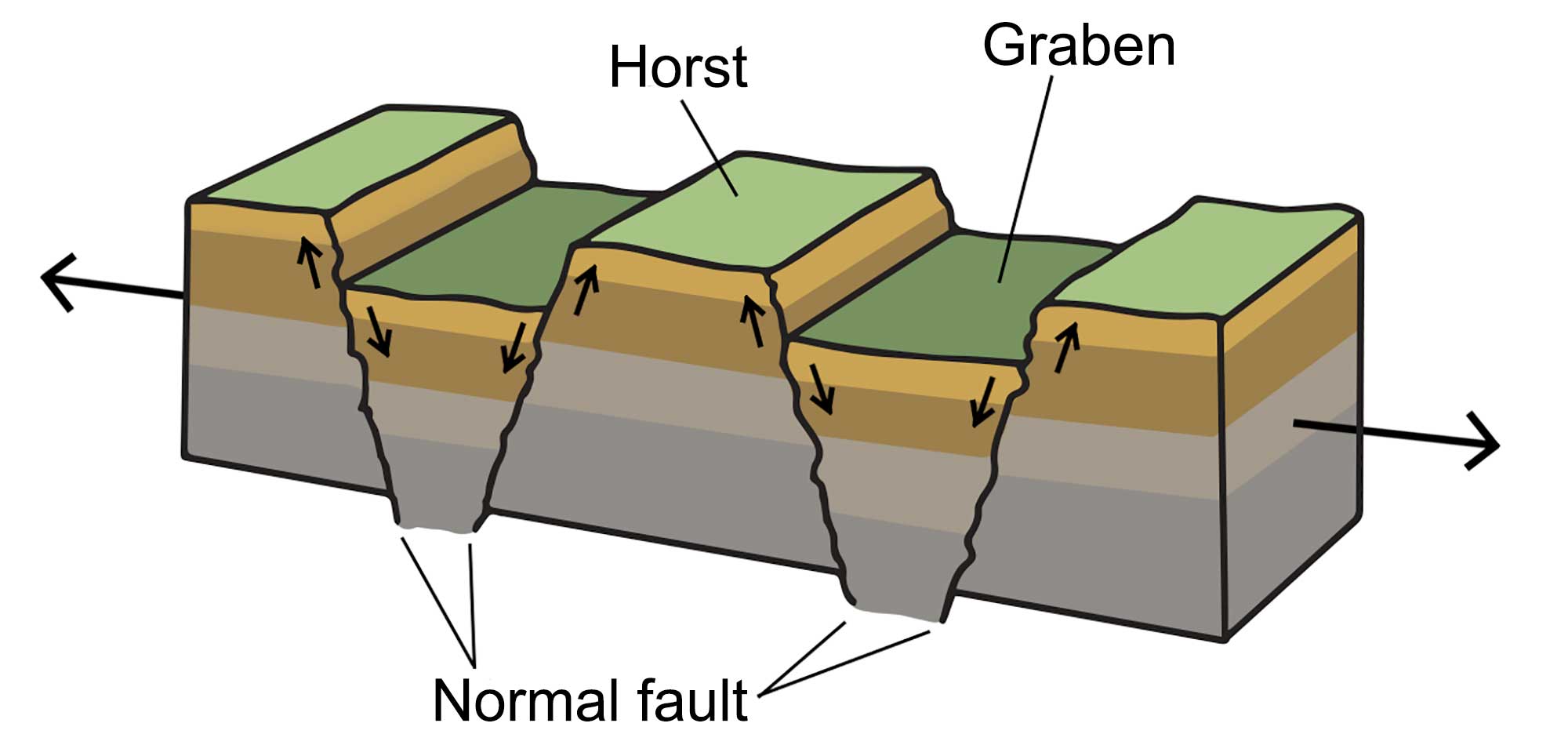

The formation of this topography is directly related to tectonic forces that led to crustal extension (pulling of the crust in opposite directions). After the Laramide Orogeny—the mountain-building event that created the Rockies—ended in the Paleogene, tectonic processes stretched and broke the crust, and the upward movement of magma weakened the lithosphere from underneath. Around 20 million years ago, the crust along the Basin and Range stretched, thinned, and faulted into some 400 mountain blocks. The pressure of the mantle below uplifted some blocks, creating elongated peaks and leaving the lower blocks below to form down-dropped valleys. The boundaries between the mountains and valleys are very sharp, both because of the straight faults between them and because many of those faults are still active. These peaks and valleys are also called horst and graben landscapes.

A horst and graben landscape occurs when the crust stretches, creating blocks of lithosphere that are uplifted at angled fault lines. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, modified for the Earth@Home project.

Such landscapes frequently occur in areas where crustal extension occurs, and the Basin and Range is often cited as a classic example thereof.

In the Basin and Range, the crust has been stretched by up to 100% of its original width. As a result of this extension, the average crustal thickness of the Basin and Range region is 30–35 kilometers (19–22 miles), compared with a worldwide average of around 40 kilometers (25 miles).

The Basin and Range’s arid climate contributes to its topography. Erosion is slow, and mechanical weathering is the dominant erosional process, partly because plants, which play a role in chemical weathering, are very sparse. The rugged mountains are fringed by large features called alluvial fans.

Alluvial fans eroding from the Panamint Range, photographed from Dante's View, Death Valley, California. Photograph by "bgwashburn" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

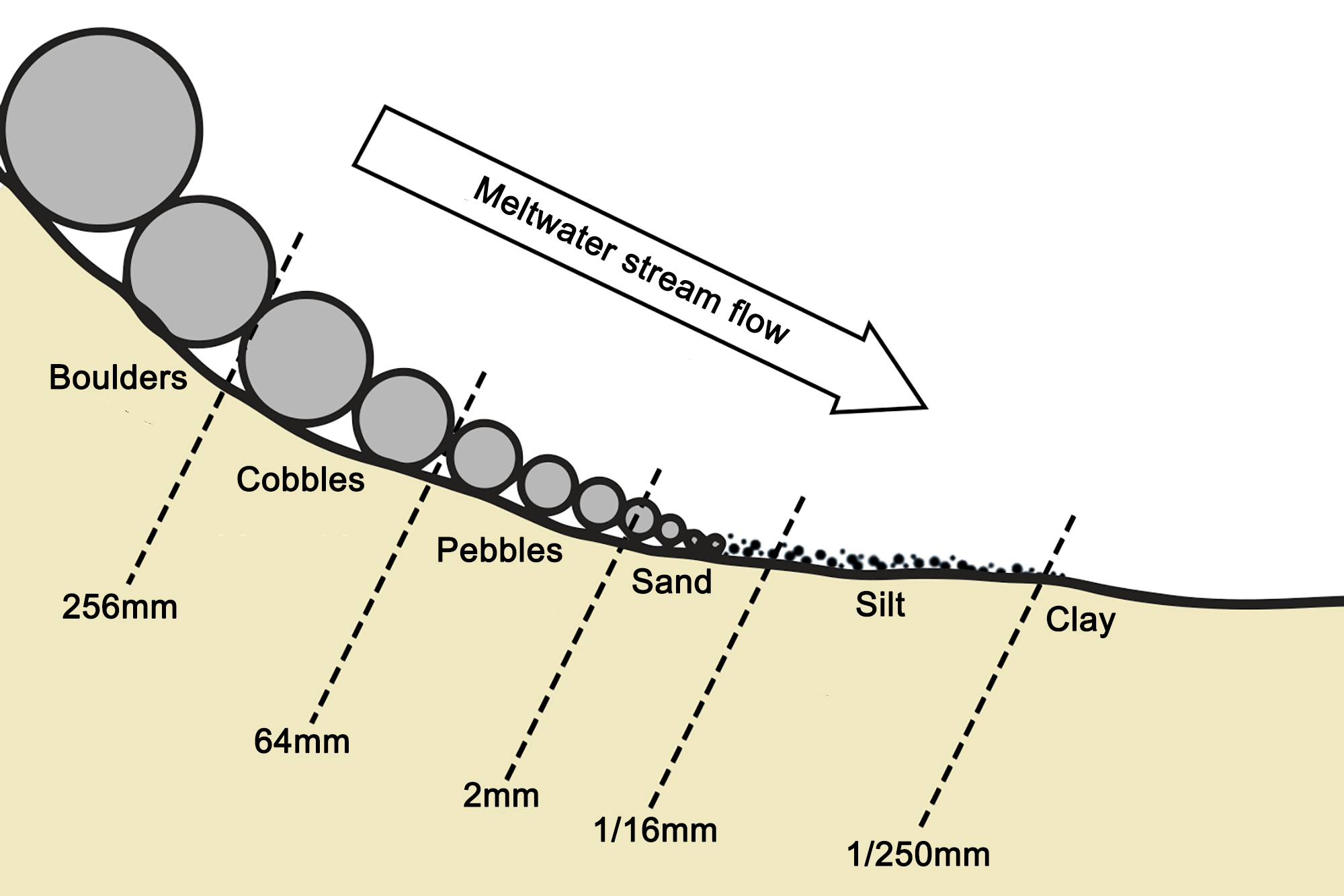

These features form when gravel and sand—and sometimes boulders—are washed out of the mountains by flash floods. The sediment is made up of large, heavy grains, and precipitates out of the water at canyon mouths, where streams lose power as they leave their channels to enter the valleys.

Moving water deposits sediments in what is known as a horizontally sorted pattern. As the water slows down (i.e., loses energy), it deposits the larger particles first. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand; modified for the Earth@Home project.

If mountain ranges are close together, alluvial fans from opposite sides of the valley will meet in the middle, but where the ranges are farther apart, valley floors will be flat and are often occupied by either playas or dune fields.