Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Central Lowland region of the Midwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Midwestern US" by Alex F. Wall, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Midwestern US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022–2023. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated July 12, 2023.

Image above: Rolling hills of the Driftless Area of Crawford County, Wisconsin along the Wisconsin River. Photograph by Corey Coyle (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; image cropped and resized).

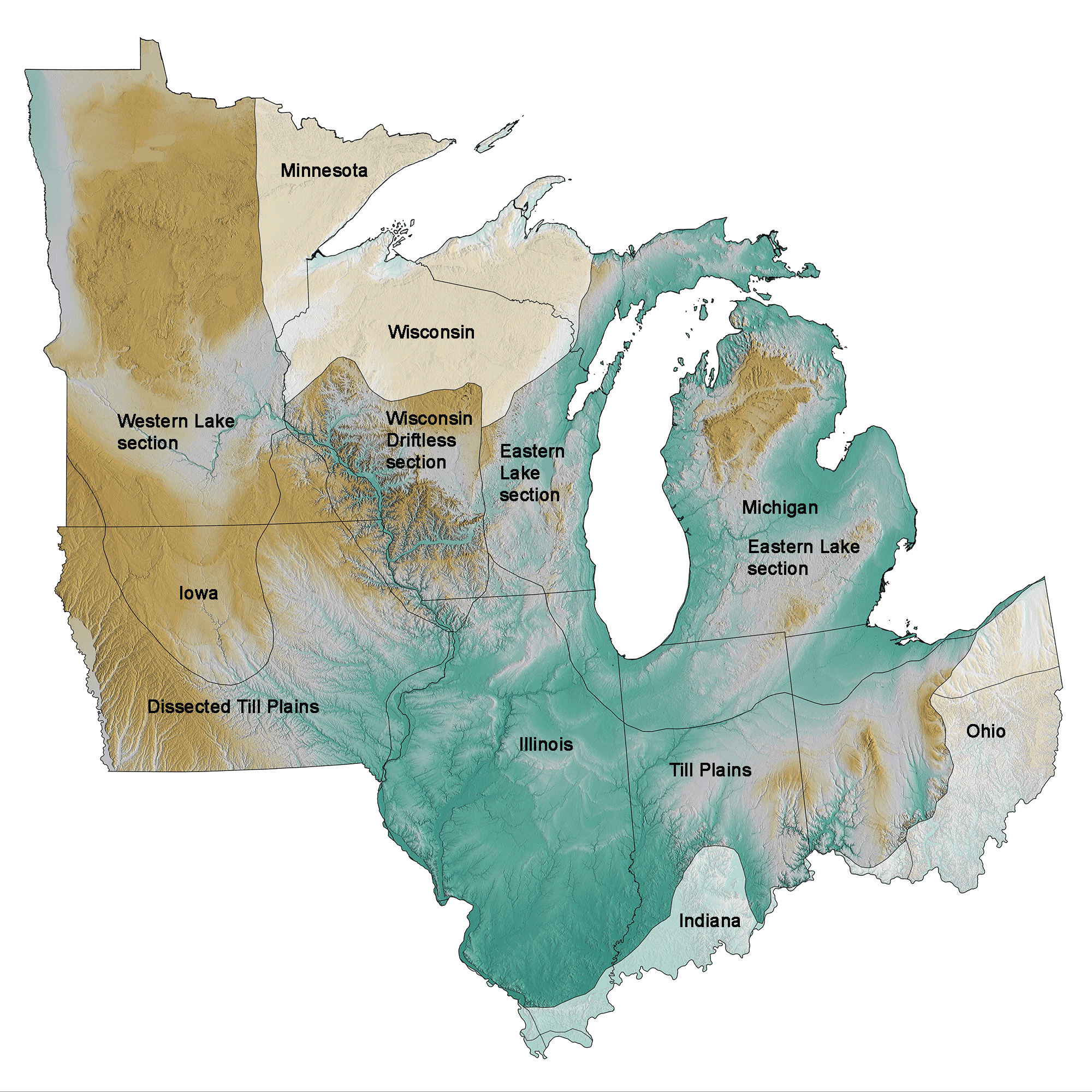

Physiographic subdivisions of the Central Lowland region of the midwestern United States; greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation; black lines indicate physiographic boundaries of other provinces. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Overview

Nearly all the bedrock in the Central Lowland is sedimentary and fairly easily eroded. During the last ice age, a series of huge ice sheets worked their way primarily southward and flattened most of whatever varied topography the region once had. Furthermore, as the glaciers retreated, they dumped sediment that formed the flatlands and the low, rolling hills that are characteristic of most of the region. There are several areas with present-day relief caused by glacial deposits, especially that created by hill-forming moraines and drumlins. While these formations stand out against the surrounding landscape, they do not usually rise more than 60 meters (200 feet) from base to peak.

Most of the topography of the Central Lowland is controlled by the rivers running through it. Since the ice last retreated from the region, rivers have had only 20,000 years, at the most, to shape the young terrain, so even the largest river valleys are not yet that deep. Within the Central Lowland, the Driftless Area may be viewed as a window into the region’s topographic past.

The Driftless Area of southwestern Wisconsin and eastern portions of Minnesota and Iowa. Image by "Wikideas1" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-share Alike 4.0 International license).

Farmland in the Driftless Area of Iowa County in southwestern Wisconsin. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

The glaciers of the last several advances did not reach as far south as where the borders of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Illinois meet, leaving that area with bedrock like the surrounding landscape but with starkly different topography. Here, streams and rivers have had hundreds of thousands, and perhaps tens of millions, of years to carve steep relief into the same types of rocks that, just miles away, glaciers recently scraped flat. Both mechanical and chemical weathering here have created a karst topography, defined by bedrock that has been affected by dissolution in water to form features like sinkholes, caves, and cliffs.

The highest points in Iowa and Illinois are both located in the Driftless Area. Given enough time, the rest of the Central Lowland might appear as the Driftless Area does today, after running water washes away the glacial sediment and cuts into the bedrock. West Blue Mound, with an elevation of 523 meters (1716 feet), is the highest point in the Driftless Area, while the Mississippi River is appreciably lower at 184 meters (603 feet). Ultimately, this does not result in huge changes in elevation, but the steep cliffs and valleys contrast dramatically with the nearby flatland.