Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Superior Upland region of the Midwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Midwestern US" by Alex F. Wall, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Midwestern US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022–2023. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated July 12, 2023.

Image above: Copper Harbor on the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, which extends northward into Lake Superior. Photograph by Rachel Kramer (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

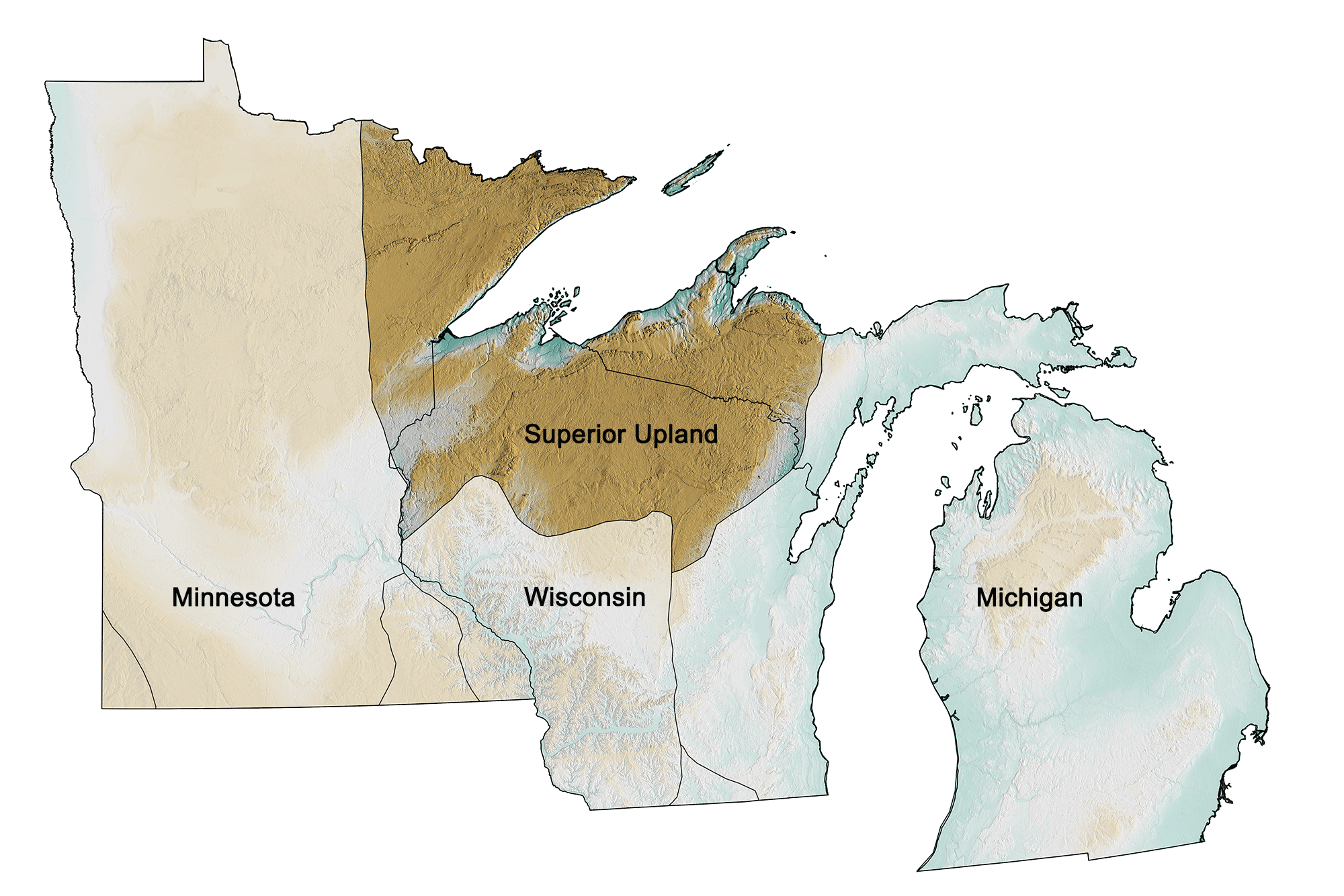

The Superior Upland region of the midwestern United States; greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation; black lines indicate physiographic boundaries of other provinces. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Overview

While the Superior Upland is not mountainous, it has a more dramatic topography than does much of the Midwest. The highest points in each of the three states in the Superior Upland are found in that region, rather than in the southern portions of the states, which are part of the Central Lowland. The ice sheets of the last ice age heavily scoured much of the Midwest, but the hard metamorphic and igneous bedrock of this region was more resistant, retaining some of the relief of the mountain ranges that once existed here. Hills reach over 610 meters (2000 feet) above sea level, while the shores of Lake Superior are at about 180 meters (600 feet), and its bottom plunges to more than 210 meters (700 feet) below sea level.

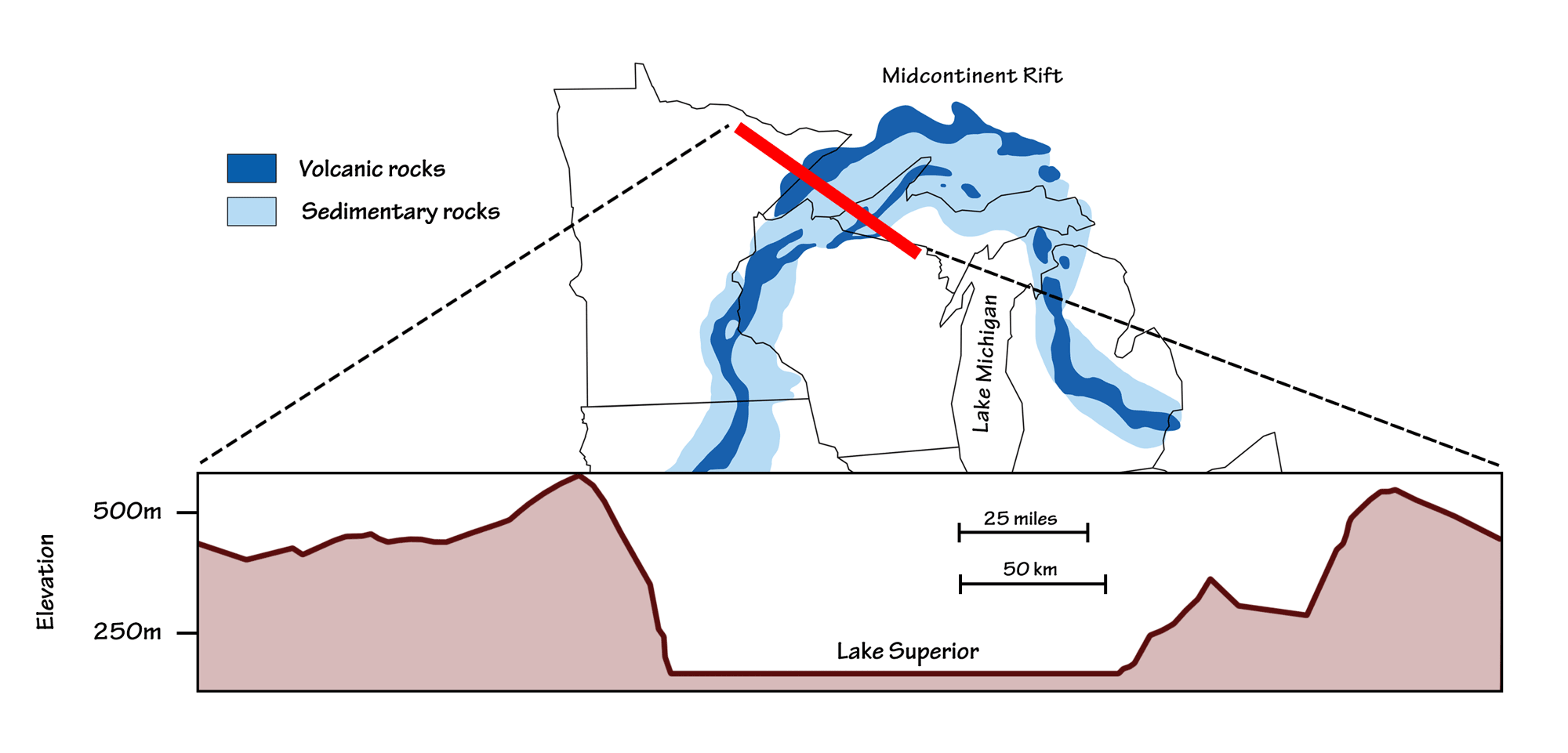

The more easily eroded igneous and sedimentary rocks created during the Midcontinental Rift event 1.1 billion years ago are partially responsible for the depth of the Great Lakes. The rifting caused a basin to form that was repeatedly filled with lava flows and sediment. When glaciers scraped across the landscape, they gouged these rocks much more deeply than they did the surrounding Archean rocks.

Cross-section showing topographic relief across rocks within the Midcontinental Rift. Topographic transect from Google Earth.

In addition to wearing down the ancient, rugged landscape, glaciers also left deposits on the Superior Upland. Much of the region has a thin layer of glacial till, but, for the most part, the topography is controlled by the underlying bedrock. The drumlin fields north of Duluth are an exception to this generality. These low hills are strongly elongated from the northeast to the southwest, indicating the direction the glaciers flowed while the sediment was deposited to a depth of 15 meters (50 feet).