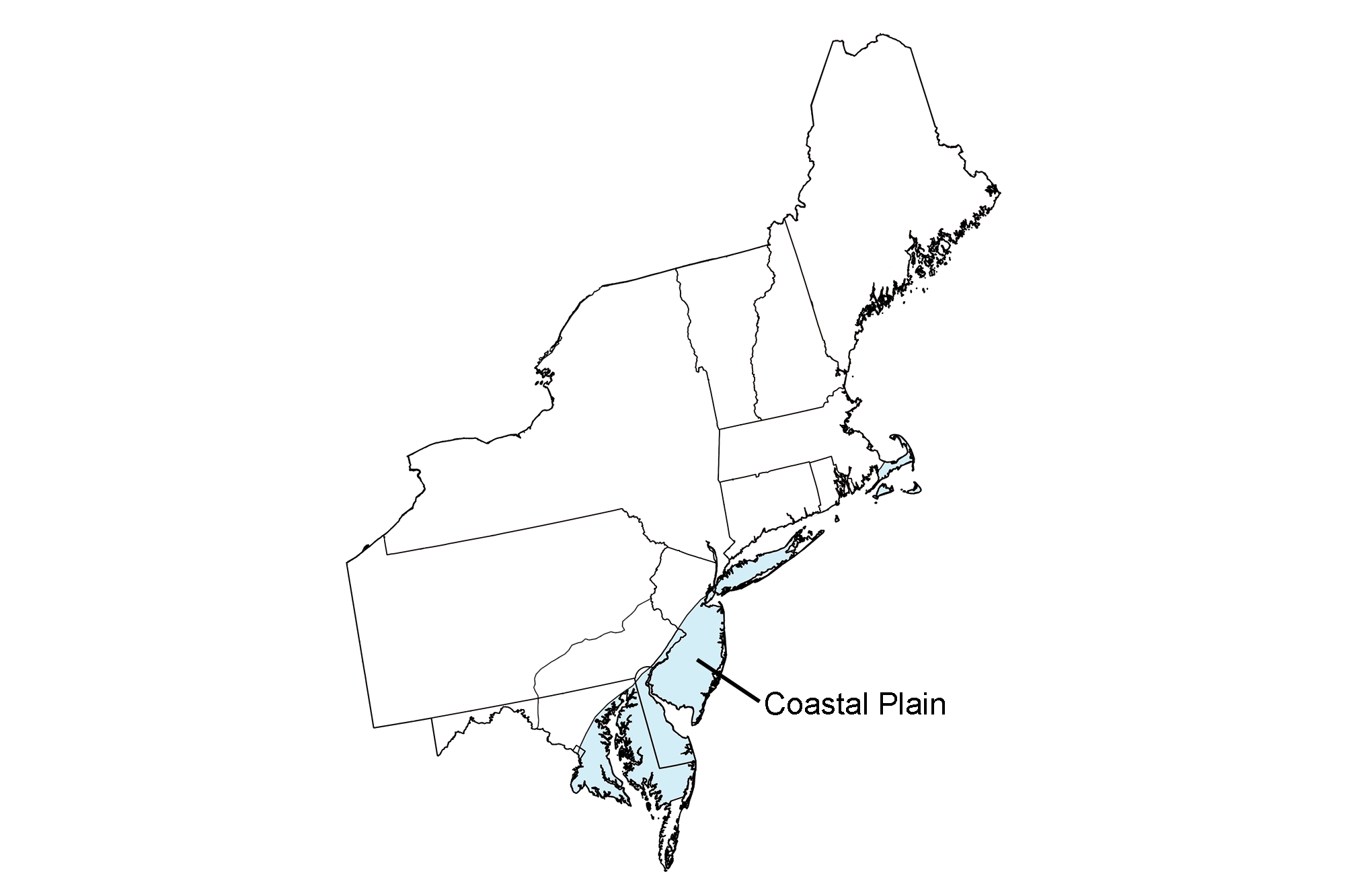

Spotlight: Overview of the fossils of the Coastal Plain region of the Northeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Cretaceous; Marine fossils of the C&D Canal; Potomac Group; Late Cretaceous; Plant and insect fossils of New Jersey; New Jersey dinosaurs; Inversand Site; Cenozoic; Paleogene; Neogene; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Rocks of the Northeastern US" by Jane Elizabeth Ansley, from The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US (published in 2000 by the Paleontological Research Institution, reprinted in 2016; currently out of print). The text was adapted for Earth@Home web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2023. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 25, 2023.

Image above: Fossil mollusk shells from the Miocene Calvert Formation, Calvert County, Maryland. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

Overview

The Coastal Plain is underlain by a wedge of flat-lying Cretaceous and Cenozoic unconsolidated sediments. These sediments preserve striking evidence of how much sea life has changed from the Paleozoic to the Cenozoic. Fossils from the Coastal Plain are very different from the Paleozoic marine fossils found in the Inland Basin and Appalachian/Piedmont regions. The Coastal Plain sediments are especially rich in mollusks (bivalves and gastropods, and, in Cretaceous sediments, cephalopods). Shark teeth, scleractinian corals, barnacles, and sand dollars are also found in the Coastal Plain but are rare or absent in Paleozoic rocks. Brachiopods, so common in Paleozoic sedimentary rocks, are all but absent in the Coastal Plain.

Cretaceous

Marine fossils of the C&D Canal

Good outcrops of marine Cretaceous fossils can be found along the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal (also called the C&D Canal) that cuts through parts of Delaware and Maryland. More than one rock unit is exposed along the canal, ranging from the Lower Cretaceous Potomac Group to the Upper Cretaceous Mount Laurel Formation, which is overlain by a cap of Quaternary sediment. Fossils include sponges, marine snails, cephalopods (ammonoids, belemnites), bivalves, shrimp, crabs, lobsters, echinoderms, sharks, turtles, and more. Outcrops with bivalves are common, especially including oysters such as Gryphaea, which in some cases created small oyster reefs. Snails, ammonoids, belemnites, and claws of the shrimp Calianassa are also common. In fact, the belemnite Belemnites americana is the state fossil of Delaware!

Belemnites (Belemnites americana), Cretaceous, Monmouth County, New Jersey. Although these belemnites did not come from the C&D Canal, similar fossils can be found there. In fact, Belemnites americana is the state fossil of Delaware. Photo of specimen YPM IP 028186 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

Potomac Group

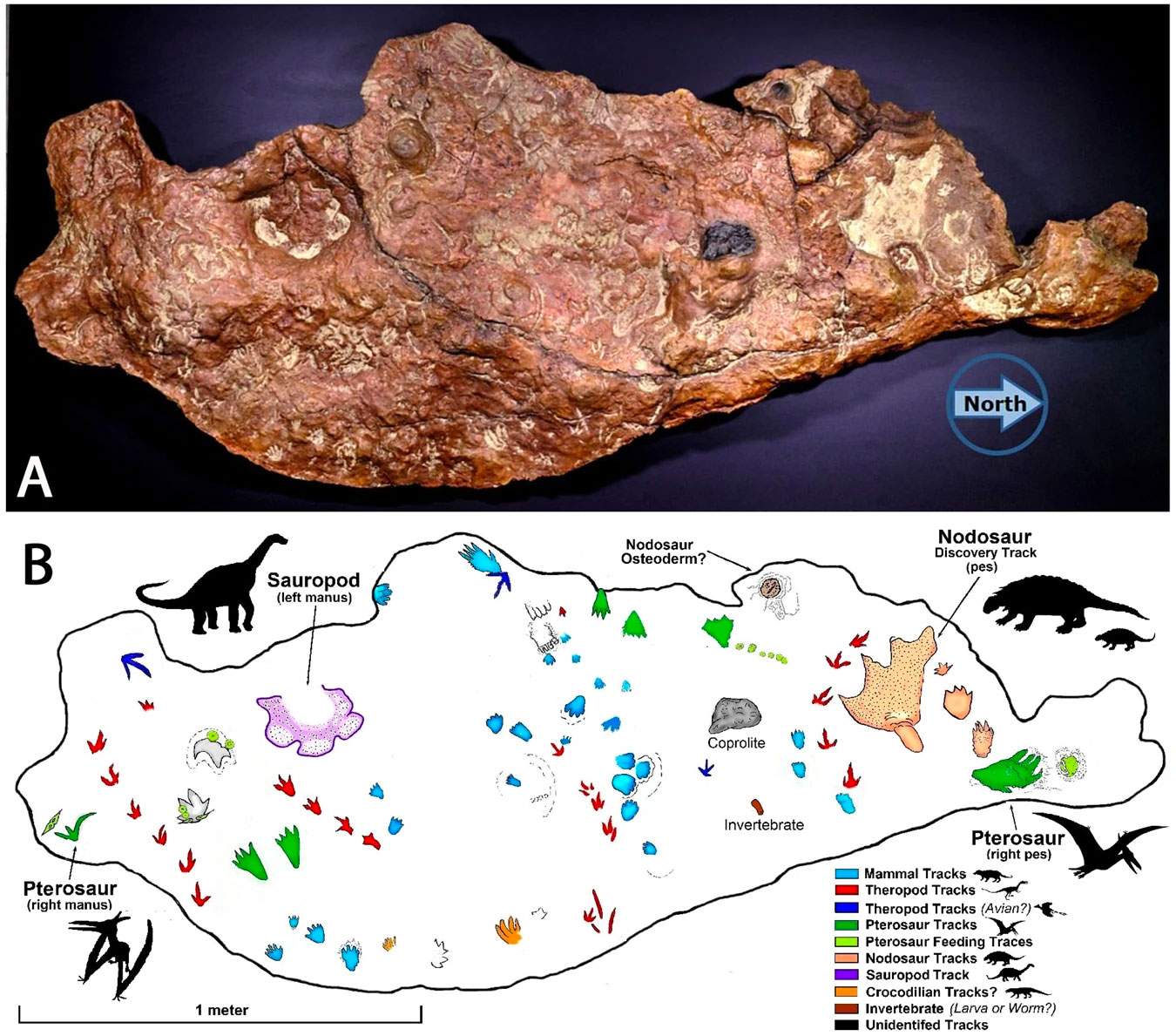

Rare remains of dinosaurs and other terrestrial vertebrate organisms have been found in the Cretaceous sediments of the Coastal Plain. The oldest of these are Lower to middle Cretaceous rocks of the Potomac Group, Maryland and Virginia, which yield fossil vertebrates and plants, as well as some tracks.

Vertebrate fossils from the Potomac Group come from the Arundel Formation (Arundel Clay), which is Aptian in age (about 121 to 113 million years old). These fossils are generally teeth or other isolated fragments, so identification is sometimes difficult. Nonetheless, the Potomac Group is known to yield carnivorous dinosaurs, although none is securely identified. Herbivorous dinosaurs include a sauropod (Astrodon johnstoni), a notosaur (Priconodon crassus), and more. Other vertebrates from the Potomac Group are mammals, crocodiles, turtles, frogs, sharks, and lungfish. Additionally, footprints of dinosaurs, pterosaurs, frogs, and mammals have been found.

Plant remains from the Potomac Group include compression and impression fossils, like imprints of fossils leaves, as well as tiny, three-dimensionally fern fragments and flowers.

A slab of rock preserving Early Cretaceous (Patuxent Formation, Potomac Group) vertebrate tracks from the campus of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. Source: Figure 3 from Standford et al. (2018) Scientific Reports 8: 741 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Late Cretaceous fossils

Plant and insect fossils from New Jersey

The old clay pits of northern New Jersey yield tiny insect and plant fossils, which provide a picture how insects and flowering plants were diversifying at the time, as well as how they may have been interacting ecologically. Many of these fossils come from the Upper Cretaceous Raritan Formation. One Raritan site, the Sayreville site, has yielded a treasure trove of ancient, three-dimensionally preserved flowers. Scientists think that these flowers may have been scorched by fires before they were preserved, because they are charcoalified.

Plants from the Sayreville site include ancient relatives of water lily (Microvictoria svitkoana), spicebush (Jerseyanthus calycanthoides), laurel (Perseanthus crossmanensis), hydrangea (Tylerianthus crossmanensis), heath (Rariglanda jerseyensis), and other angiosperms (flowering plants), as well as fern and conifer remains. One of the more interesting finds are flowers of triurids (Mabelia and Nuhliantha), parasitic plants that are today occur in the tropics worldwide. Stingless bees found at the site may have collected resin from clusia-like flowers (Paleoclusia chevalieri), as they still do today. Notably, Late Cretaceous plant fossils with similar preservation to those from the Sayreville site have also been found on Martha's Vineyard and in the Coastal Plain of the Southeast.

Amber also occurs in Late Cretaceous New Jersey clays. New Jersey amber preserves a diverse insect fauna as well as occasional plant inclusions.

A fossil wasp (Plumalexius rasnitsyni) in amber, Late Cretaceous, New Jersey. Source: Brothers (2011) ZooKeys 130: 515-542 (Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped).

New Jersey dinosaurs

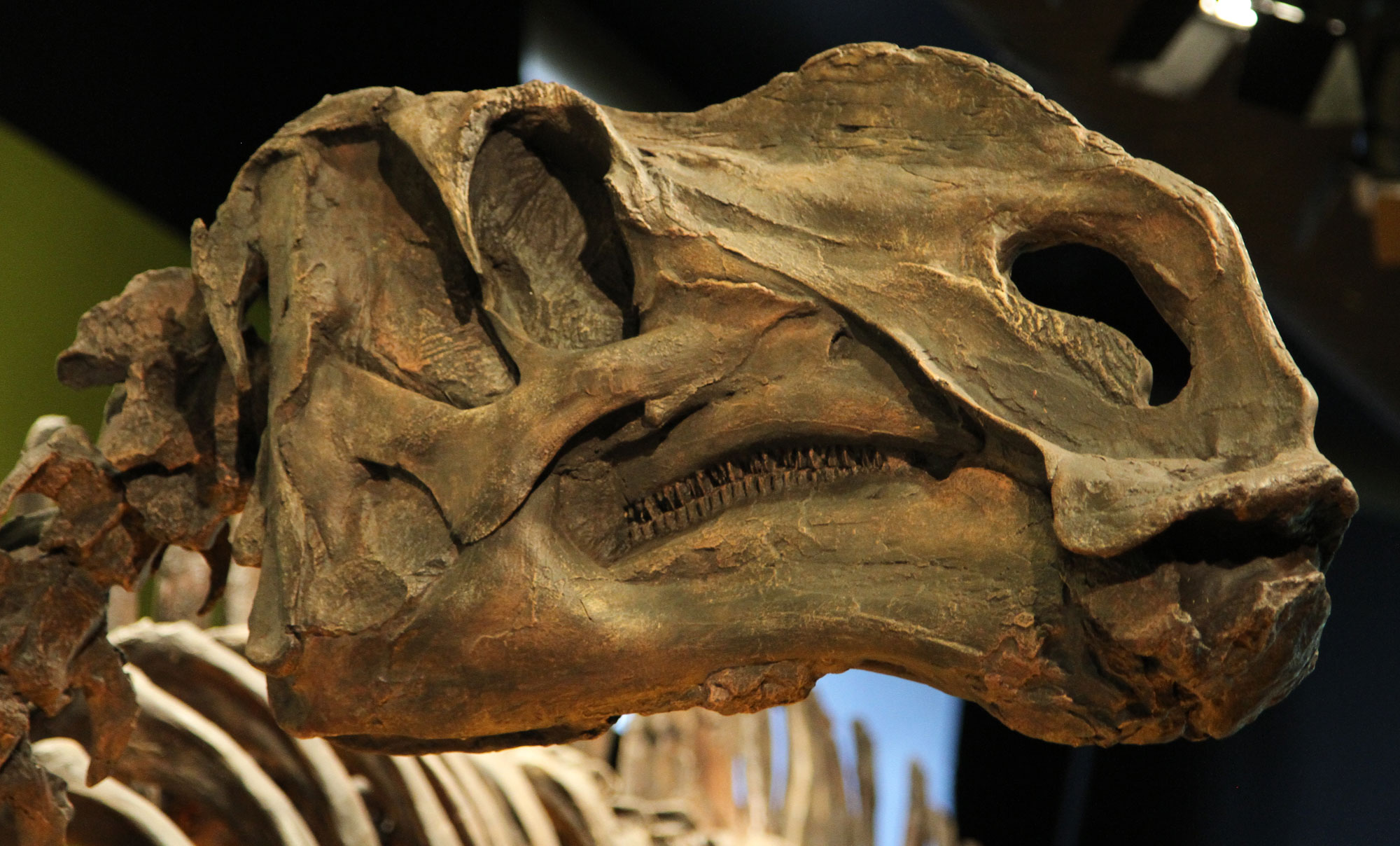

Perhaps the most celebrated discovery was that of a duck-billed dinosaur known as Hadrosaurus foulkii in Haddonfield, New Jersey. Some Hadrosaurus foulkii bones were first discovered by John Estaugh Hopkins in 1835. However, more of the skeleton was not unearthed until the late 1850s, when a friend of Hopkins took an interest in excavating more bones and enlisted the help of scientist Joseph Leidy, who determined that they were from a dinosaur that stood on its hind legs. (Today, Hadrosaurus is thought to have walked mainly on four legs.)

This was the first dinosaur skeleton in the world to be mounted and put on display in a museum; it is currently on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Hadrosaurus foulkii was named New Jersey's state dinosaur in 1991. The site where the original skeleton was found is in Camden County Park, Haddonfield, New Jersey, and is marked by a plaque; it is a National Historic Landmark.

The skull of Hadrosaurus foukii from New Jersey, specimen on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. Photograph by Jim, the Photographer (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Drawn to Dinosaurs: Hadrosaurus foulkii. Drexel University (YouTube).

Another important nineteenth century dinosaur discovery from New Jersey was the partial skeleton of the predatory dinosaur Dryptosaurus (originally called Laelaps), a type of tyrannosaurid, which was found in the 1860s. Dryptosaurus is probably most familiar from a famous painting by the paleontological artist Charles R. Knight called Leaping Laelaps (1897). This painting shows two Dryptosaurus fighting, an active depiction of dinosaurs that was unusual for its time. A display of Dryptosaurus skeletons at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, New Jersey, replicates the poses of the dinosaurs in the painting. Because no complete Dryptosaurus skeletons have been found, the skeletons on display have been reconstructed partially based on the skeletons of related dinosaurs.

"Leaping Laelaps," a painting of fighting Drypotosaurus by Charles R. Knight, 1897. Source: Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

A display of fighting Dryptosaurus aquilunguis inspired by the art of Charles R. Knight. Photo by Skye McDavid (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license, image cropped and resized).

Inversand Site

New Jersey's greensand quarries historically yielded important vertebrate finds, such as the Dryptosaurus noted above. In modern times, these quarries have been replaced with developments, and now many of these sites are no longer available to paleontologists for study.

One major greensand quarry site in New Jersey that is being preserved for the future is the Inversand Site, a former greensand quarry in Mantua, New Jersey. This site, now called the Jean and Ric Edelman Fossil Park and Museum of Rowan University, yields Late Cretaceous invertebrate and vertebrate fossils, such as sponges, corals, brachiopods, clams, oysters, gastropods, belemnites, shark teeth, and remains of turtles, crocodiles, mosasaurs, and dinosaurs.

Shark vertebra from the latest Cretaceous Inversand Dig Site/Edelman Fossil Park in Mantua, New Jersey. Photo by Rowan-earth (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Shark teeth (Cretolamna) from the latest Cretaceous Inversand Dig Site/Edelman Fossil Park in Mantua, New Jersey. Photo by Rowan-earth (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Part of a mosasaur jaw from the latest Cretaceous Inversand Dig Site/Edelman Fossil Park in Mantua, New Jersey. Photo by Rowan-earth (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Cenozoic

Paleogene

Paleogene sediments of the Coastal Plain have been studied since the early 1800s, longer than almost any other fossil-bearing sediments in the Americas. Coastal Plain deposits are often very fossiliferous and some are among the most famous Paleogene fossil beds in the world.

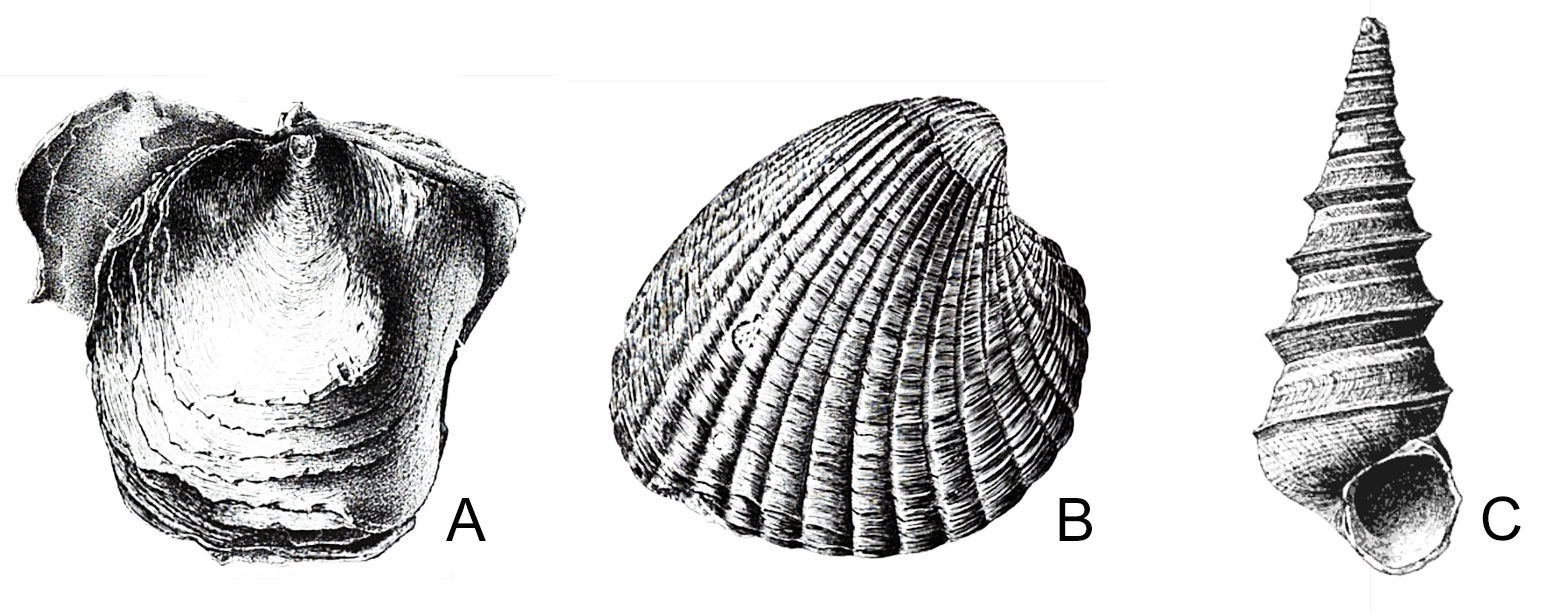

Fossil mollusks—mainly clams and snails—of Paleogene age occur across the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal Plains, from Maryland to Texas. They are frequently found in beautifully preserved shell beds that may contain hundreds of different species. In total, more than 3000 species of mollusks have been described from the Paleogene of the Coastal Plain.

Paleogene mollusks from the Atlantic Coastal Plain. A. An oyster (Ostrea sellaeformis), Nanjemoy Formation, Virginia (width = 15 cm or 6 in). B. A clam (Venericardia planicosta var. regia), Aquia Formation, Maryland (width = 7.5 cm or 3 in). C. A marine snail (Turritella mortoni), Aquia Formation, Maryland (height = 10 cm or 4 in). Drawings A–C from Clark & Martin (1901) The Eocene Deposits of Maryland.

Shells from the Paleocene Aquia Formation, Maryland. Photo of specimen YPM IP 009110 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum, 2021 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

Fossil brachiopod specimen of Oleneothyris harlani from the Eocene of New Jersey (PRI 76901). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimention of specimen is approximately 6 cm. Model by Jaleigh Pier.

Neogene

The best-known fossil-rich sections of the Paleogene to Neogene Coastal Plain deposits in the Northeast are at Calvert Cliffs in Maryland (these deposits continue into Virginia and North Carolina in the Southeast). Barnacles, crab claws, sand dollars, and bryozoans are present in relatively small numbers, in addition to the abundant mollusks that characterize deposits in the Coastal Plain region. Among the vertebrate fossils found at Calvert Cliffs have been inner ear bones, teeth, and vertebrae of many species of whales and porpoises, shark teeth, ribs, jaws, crocodile teeth, turtle remains, stingray spines and teeth, and skeletal elements of bony fish. There is one species of brachiopod, an organism that had dominated the Paleozoic sea.

People search for fossils on the beach in front of the Calvert Cliffs at Calvert Cliffs State Park in Maryland. The Cliffs are made up of Miocene-aged sediments. Photo by Chesapeake Bay Program (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Sea stars (Asteriacites), Miocene St. Marys Formation, Maryland. Photo of specimen YPM IP 524790 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum, 2017 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

A scallop (Pecten jeffersonius), Miocene, St. Mary's County, Maryland. Photo of specimen YPM IP 025520 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum, 2012 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

Fossil geoduck clam Panopea americana from the Miocene Choptank Formation at Calvert Cliffs, Maryland (PRI 50574). Specimen is on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 17 cm. Model by Emily Hauf.

A whelk (Busycotypus coronatum), Miocene, St. Marys Formation, Calvert County, Maryland. Photo of specimen YPM IP 025520 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum, 2012 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

Fossil specimen of the echinoid Echinocardium orthonotum from the Miocene of Maryland (PRI 503). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 5 cm. Model by Emily Hauf.

Tooth of a shark-toothe porpoise (Squalodon atlanticus), Miocene, Randle Cliff, Calvert County, Maryland. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central U.S.: Fossils of the Coastal Plain (continues coverage of the Gulf Coastal Plain in Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-cp/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Coastal Plain (continues coverage of the Gulf Coastal Plain in Alabama, Florida, and Mississippi, as well as the Atlantic Coastal Plain north to Virginia): https://earthathome.org/hoe/se/fossils-cp/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/