Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Inland Basin and Central Lowland region of the northeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Allegheny Plateau; Adirondacks; Lowlands; Valley and Ridge; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Northeastern US: the BIG picture" by Jane E. Ansley, chapter 5 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Northeastern U.S. (published in 2000 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2020–2023. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated September 18, 2023.

Image above: The Adirondack Mountains of New York at Saranac Lake. Photograph by Bill Badzo (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercia-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

Overview

The Inland Basin has three main topographic divisions: the Allegheny Plateau, the Adirondacks and the Lowlands. The existence of the basin itself is due to the downward buckling of the crust at the onset of the Taconic and Acadian mountain-building events. What makes the Inland Basin distinct from the other regions of the Northeast are the structure and nature of the sedimentary rocks that fill the basin. Unlike the Appalachian/Piedmont region or the complexly deformed Exotic Terrane region, the surface rocks of the Inland Basin have been gently tilted and folded, and were far enough removed from the mountain-building events to have escaped being metamorphosed. The exception to this pattern is the Adirondack region, where uplift independent of the Paleozoic mountain-building events raised bedrock metamorphosed during the late Precambrian to the surface as erosion removed the overlying Inland Basin sedimentary layers.

Allegheny Plateau

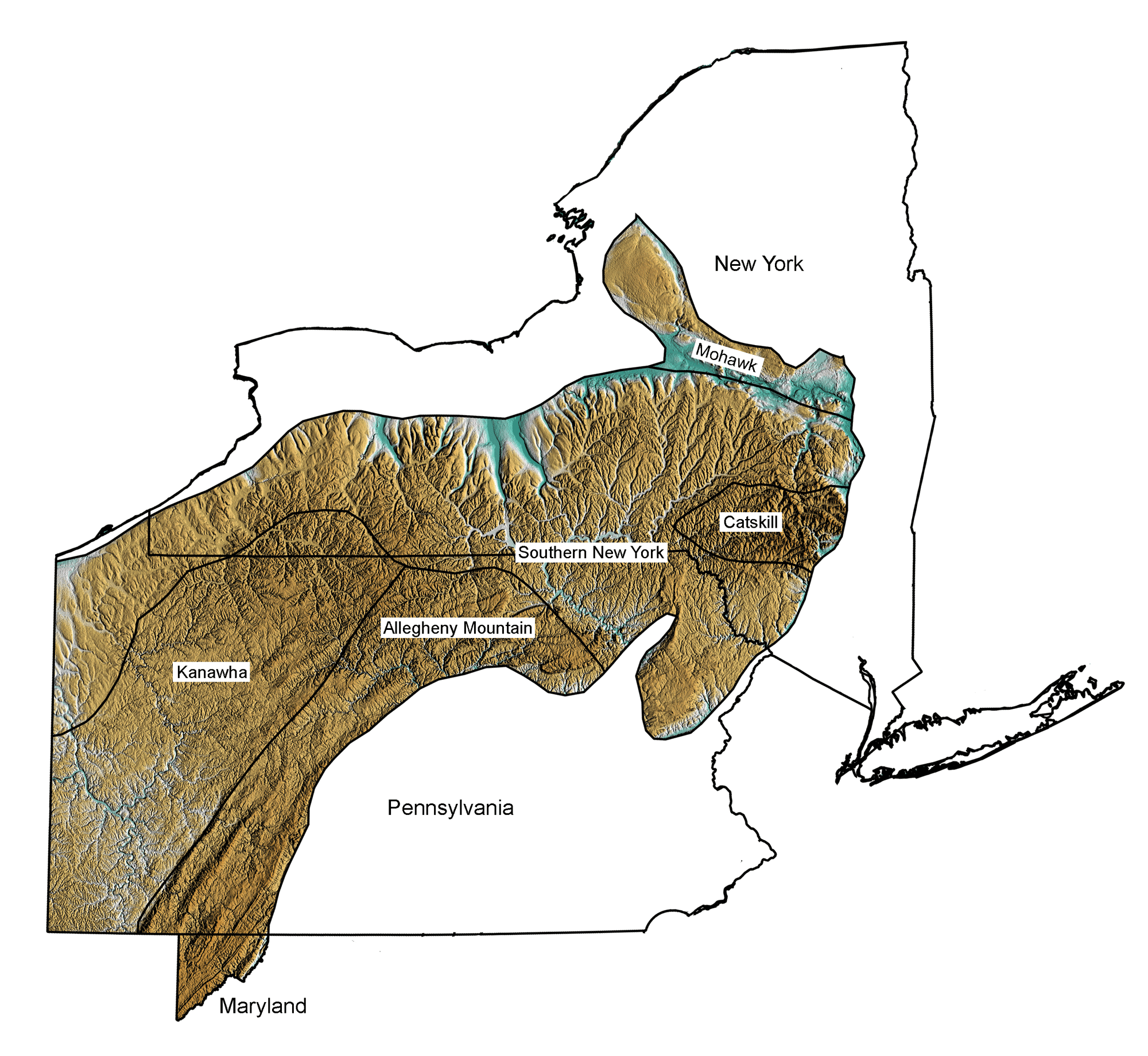

The Allegheny Plateau dominates much of the Inland Basin region, extending from the southern tier of New York, southward through western Pennsylvania and Maryland to Alabama.

Topography of the Allegheny Plateau region of New York, Pennsylvania, and far western Maryland, with subregions identified. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project. The topographic data are derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583); greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation

The layers of rock within the plateau have been only gently folded and tilted slightly to the south during the final mountain-building event during the Permian. A drive through the Allegheny Plateau region reveals a landscape contrary to the common concept of a plateau as an elevated flat-topped region. The Allegheny Plateau was probably flat, but since its uplift 400 million years ago it has been deeply dissected by streams, making the area quite hilly and in some places even mountainous in appearance. The Plateau is bounded on the eastern side by the Allegheny Front, a scarp separating it from the Appalachian Mountains.

Shawangunk Ridge, viewed from the north facing southward (east is to the left, west is to the right). Photograph by Jarek Tuszyński (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license; image cropped relative to original). Author's original caption: "Shawangunk Ridge visible from Skytop cliff tower near Mohonk Mountain House. The closer cliff is called the Trapps, the second (hardly visible) is Near Trapps cliff and in the back one can see Millbrook Mountain. Hudson Valley visible to the left."

The scarp includes the white cliffs of the Shawangunk Ridge that extend southwest from the Hudson River into New Jersey and Pennsylvania, where it is known as Kittatinny Mountain. The Catskill Mountains form the eastern boundary of the Allegheny Front in New York. They are often called one-sided mountains because there is a steep scarp on the eastern side, but the west side has a gentle slope that grades more gradually into the surrounding provinces. The layers of rocks forming the Catskills are the Devonian sedimentary beds of the Catskill Delta, created during the Acadian mountain-building event as sediment eroded from the Acadian highlands. The mountains are thus unusual, as the rocks are flat lying and the relief over the area comes from deep erosion of the flat-lying layers. The elevation in the Catskills is much higher than other parts of the Allegheny Plateau because of the thicker sequences of sediments deposited on the eastern side of the Catskill Delta (closer to the Acadian highlands) and erosional differences by glaciers during the last ice age.

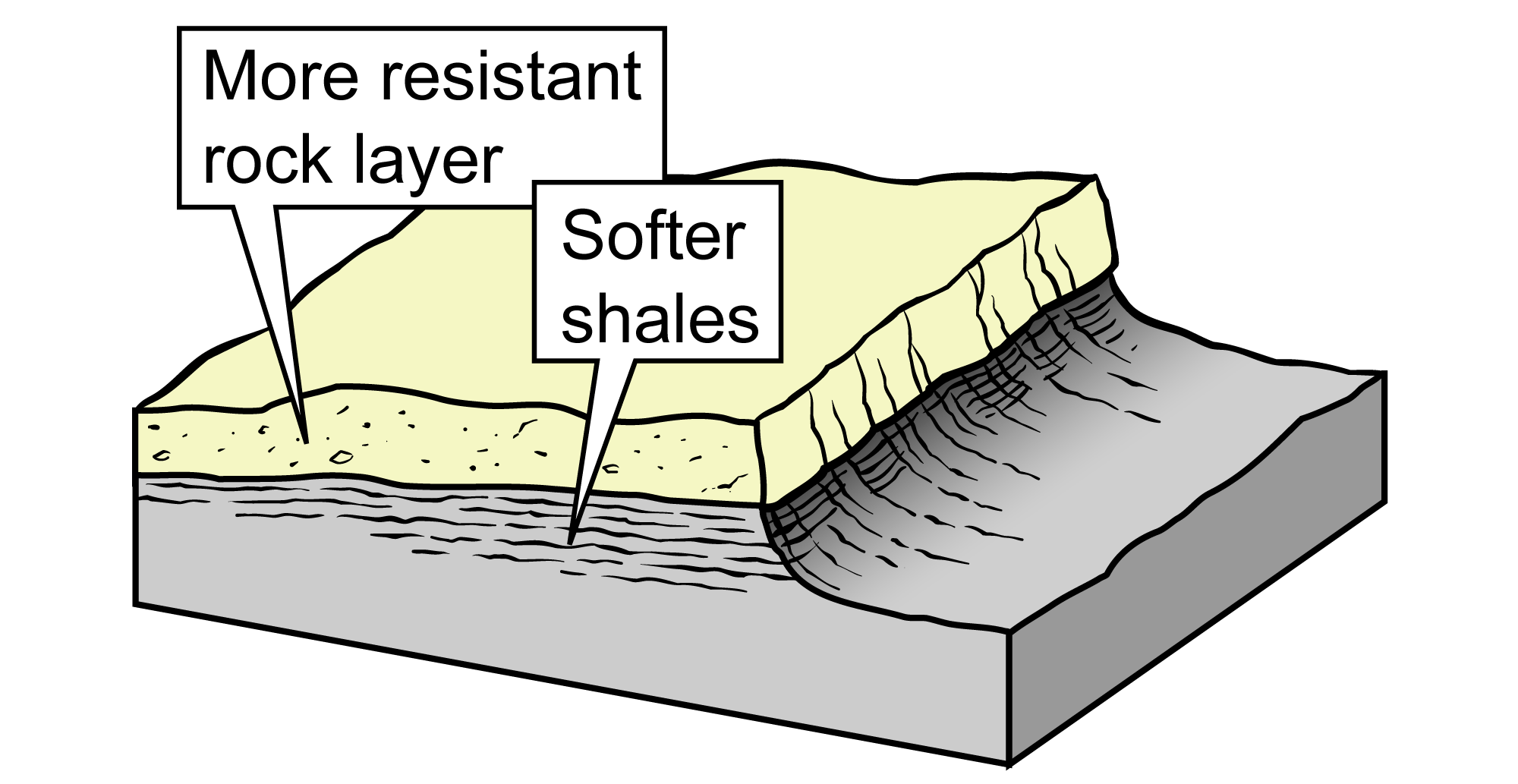

The Paleozoic sedimentary rock layers of the basin, tilted just a few degrees to the south, form many of the east-west ridges that stretch across New York. These gentle ridges are called cuestas, formed from the more resistant layers of tilted rocks, while the softer surrounding rocks have eroded away. The tilting most likely occurred during the Permian Alleghanian mountain-building event, the final crunch on the east coast of North America.

A cuesta ridge is formed from a resistant layer of gently tilted rock. Figure modified from original by J. Houghton in the Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Northeastern U.S. by J. Ansley (2000).

Adirondacks

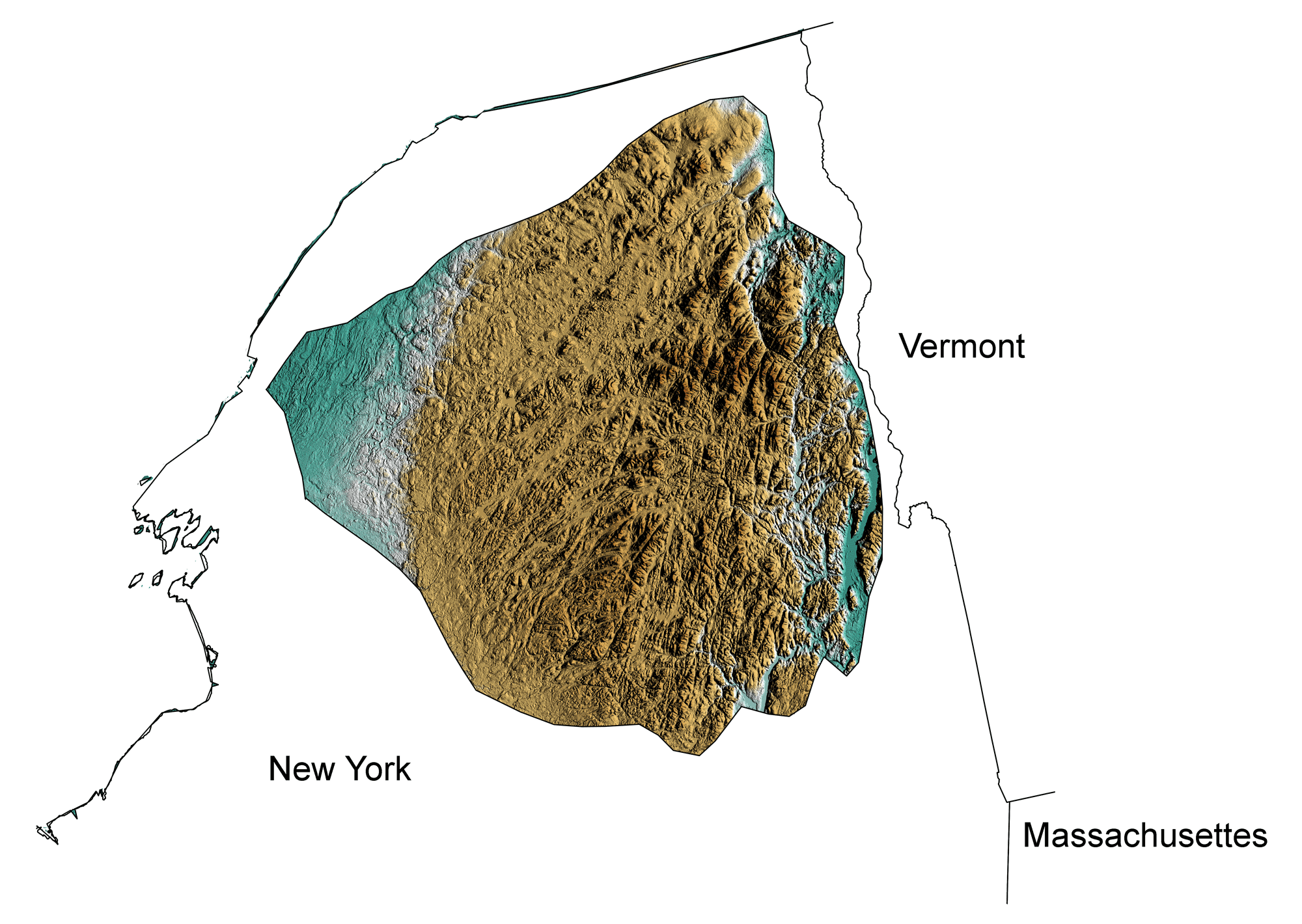

The Adirondacks loom high over the surrounding lowlands.

Topography of the Adirondacks region of New York. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project. The topographic data are derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583); greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation

Uplifted during the late Mesozoic and Tertiary, much of this mass of crystalline metamorphic Precambrian rock is extremely resistant to erosion. The surrounding lowland rocks are considerably less resistant and are made of much younger sedimentary rocks. Both the relatively recent uplift of the area and the resistant metamorphic rocks contributed to the height of the Adirondacks. Additional scouring by glaciers during the ice age helped to carve the Adirondack peaks.

Lowlands

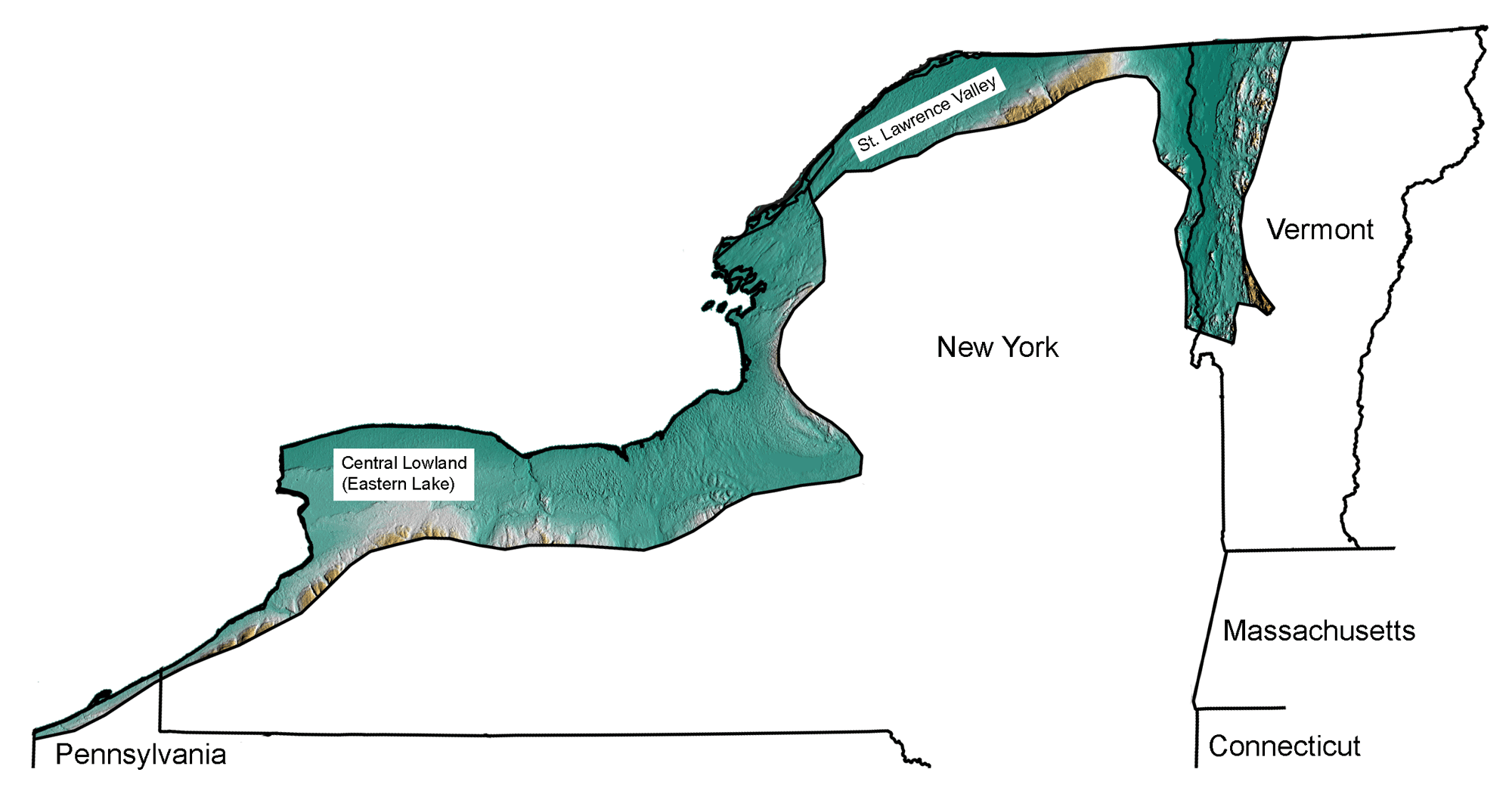

The Lowlands of the Inland Basin surround the Adirondack region on all sides, including the Erie, Ontario, St. Lawrence and Mohawk Valley lowlands.

Topography of the Lowlands region of New York and Vermont, with subregions identified. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project. The topographic data are derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583); greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation

Many of the topographic features of the Lowlands region were formed during the most recent Ice Age. The Lowlands preserve remnants of large glacial lakes scoured by glaciers and filled with glacial meltwater as the continental ice sheet advanced and retreated over the Northeast. The region of Lake Ontario was formerly occupied by a series of glacial lakes, including Glacial Lake Iroquois. The Tug Hill Plateau, which is actually a part of the Allegheny Plateau has been isolated through erosion by meltwater escaping through the present Mohawk Valley from former Lake Iroquois. As the glacial lakes shrunk, or altogether disappeared, characteristic glacial lake deposits were left behind: sand, silt and clay, and other evidence of ancient shorelines. Many striking glacial features are evident within the Lowlands, including thousands of drumlins in the Ontario Lowlands.

Valley and Ridge

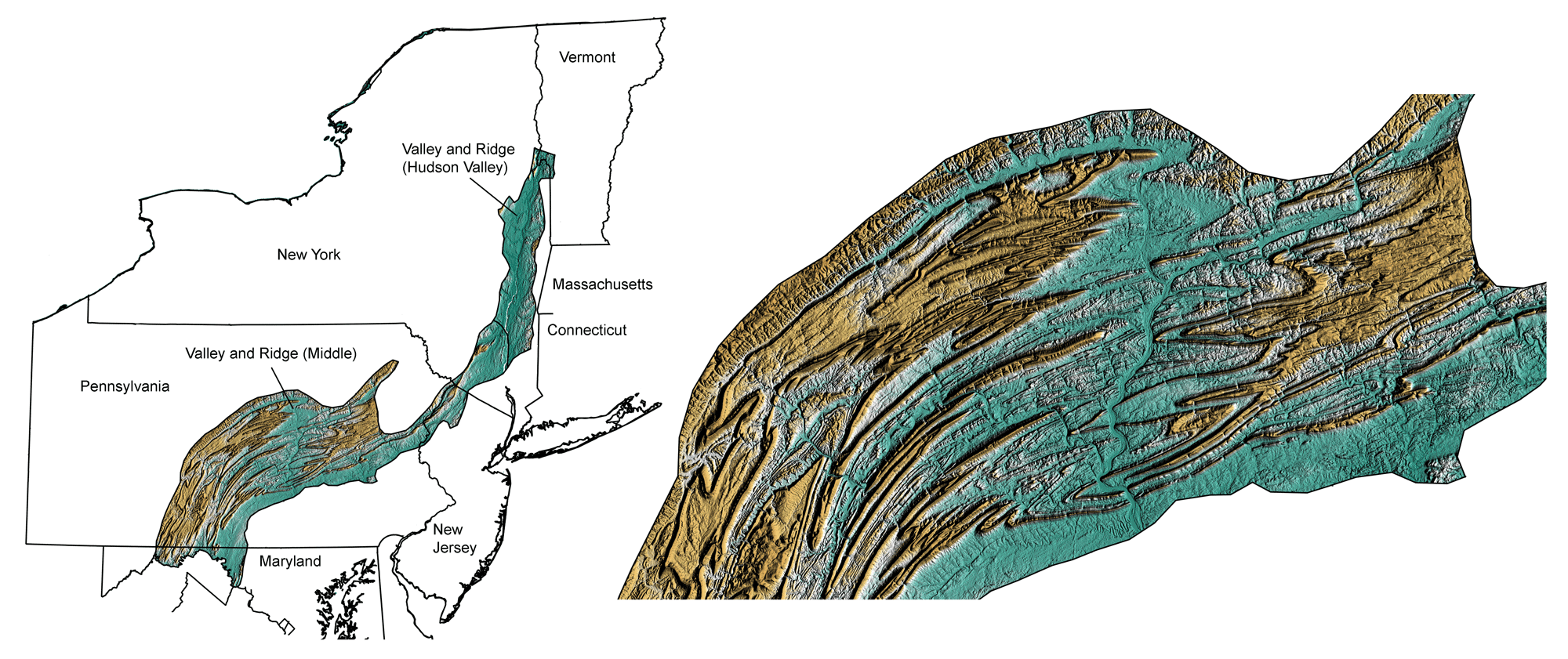

The Valley and Ridge region is bounded by the Great Valley to the east and the Allegheny Plateau of the Inland Basin to the west. Tight, narrow folds in the layers of rock from the final Alleghanian mountain-building event, created the long thin ridges and valleys throughout the province, with relief between 300 and 1000 meters or more.

Topography of the Valley and Ridge region of Vermont, New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, with subregions identified. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project. The topographic data are derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583); greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation

The Valley and Ridge region of Pennsylvania (view to the east). Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

These folds are much tighter than the broad bends of the adjacent Allegheny Plateau region to the west. Sandstone and quartzite make up the ridges of the Valley and Ridge region; more easily eroded shale, limestone and dolostone floor the valleys. The valleys are commonly formed from rock layers that have been folded upward and eroded in the center; ridges in the region often form from rock layers that have been folded downward, with resistant centers. This is known as topographic inversion, because one would expect ridges to form from upfolds and valleys to form from downfolds.