Snapshot: Overview of the topography of the Columbia Plateau and Basin and Range regions of the northwest central United States in Idaho.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Columbia Plateau; Basin and Range; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Northwest Central US" by Libby Prueher and Andrielle Swaby, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northwest Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 17, 2022.

Image above: A cinder cone and lava fields at Craters of the Moon National Monument in Butte County, Idaho. Photograph by "arbyreed" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

Columbia Plateau

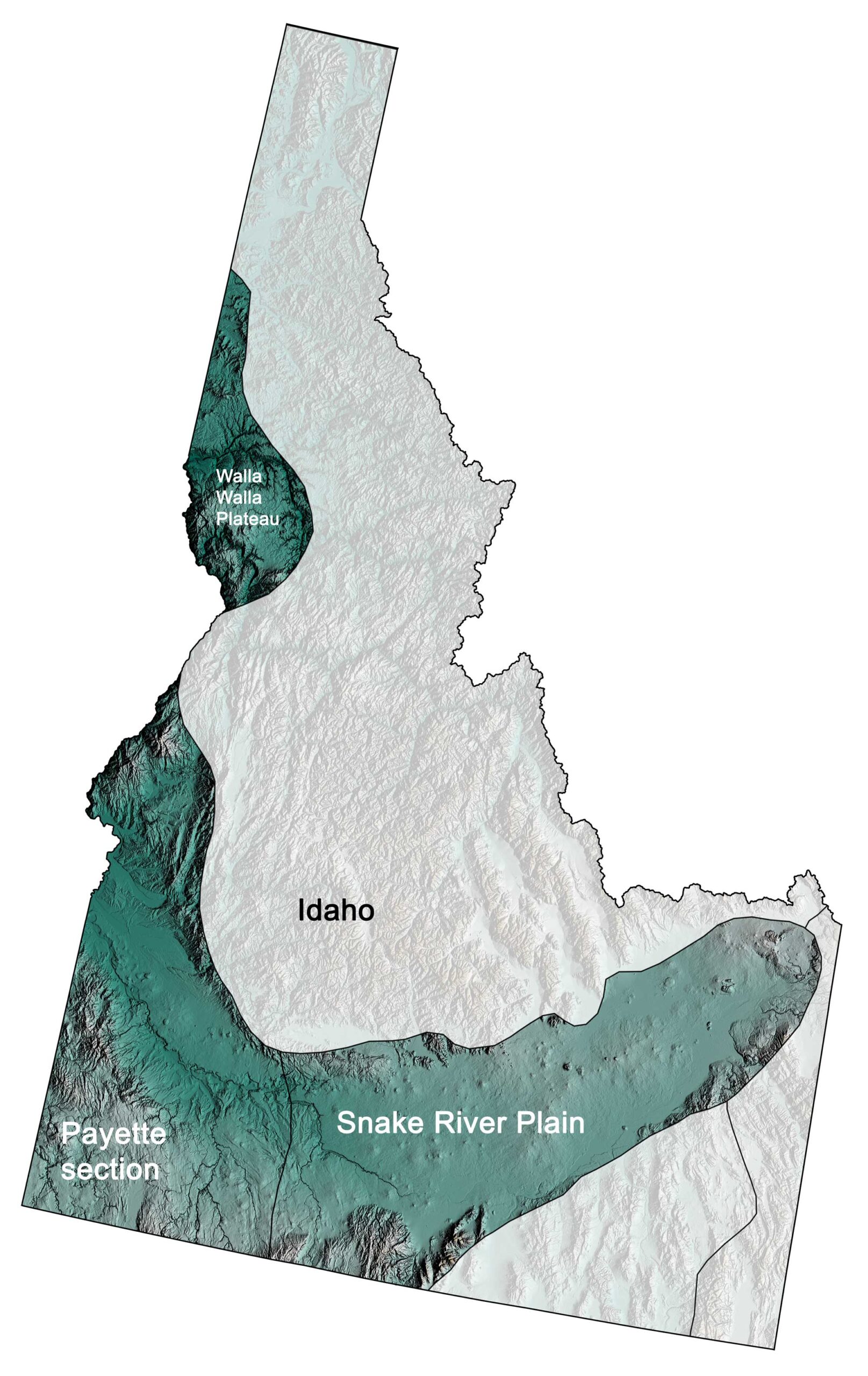

Physiographic subdivisions of the Columbia Plateau region of the northwest central United States; greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation; black lines indicate physiographic boundaries of other provinces. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

The Columbia Plateau lies to the west of the Rocky Mountains in eastern Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. This region, also called the Columbia Basin, is a broad, volcanic plain composed of basalt. Basalt solidifies from lavas that are very fluid when hot, and the basalt lava in this area erupted along a series of fractures in eastern Oregon between 17 and 14 million years ago. The basalt was so voluminous and fluid that it completely filled the preexisting topography, forming a broad, flat plain that tilts downward to the west. Geologists believe that some of these lava flows were 30 meters (100 feet) high, and flowed at speeds of up to 5 kilometers (3 miles) per hour. The Columbia Plateau also includes an area of volcanic materials erupted from the Yellowstone hot spot onto the relatively flat Snake River Plain. In the Northwest Central, the Columbia Plateau can be divided into the Walla Walla Plateau, the Payette Section, and the Snake River Plain (see map above).

The Walla Walla Plateau is covered by flood basalt, and, in fact, one basalt flow in western Idaho, the Imnaha basalt, is 900 meters (2950 feet) thick. Some rivers were able to cut through the basalt, forming deep canyons.

Hells Canyon, near Wallowa along the Oregon-Idaho border, cuts deeply through the Columbia Flood Basalt. Photograph by "Linda, Fortuna future" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license).

The presence and thickness of sediment varies on this plateau since some of the small rivers in this area were dammed by the basalt flows, forming lakes where sedimentation could occur. In some places, thick layers of wind-blown glacial sediment were deposited, eroding to form hills.

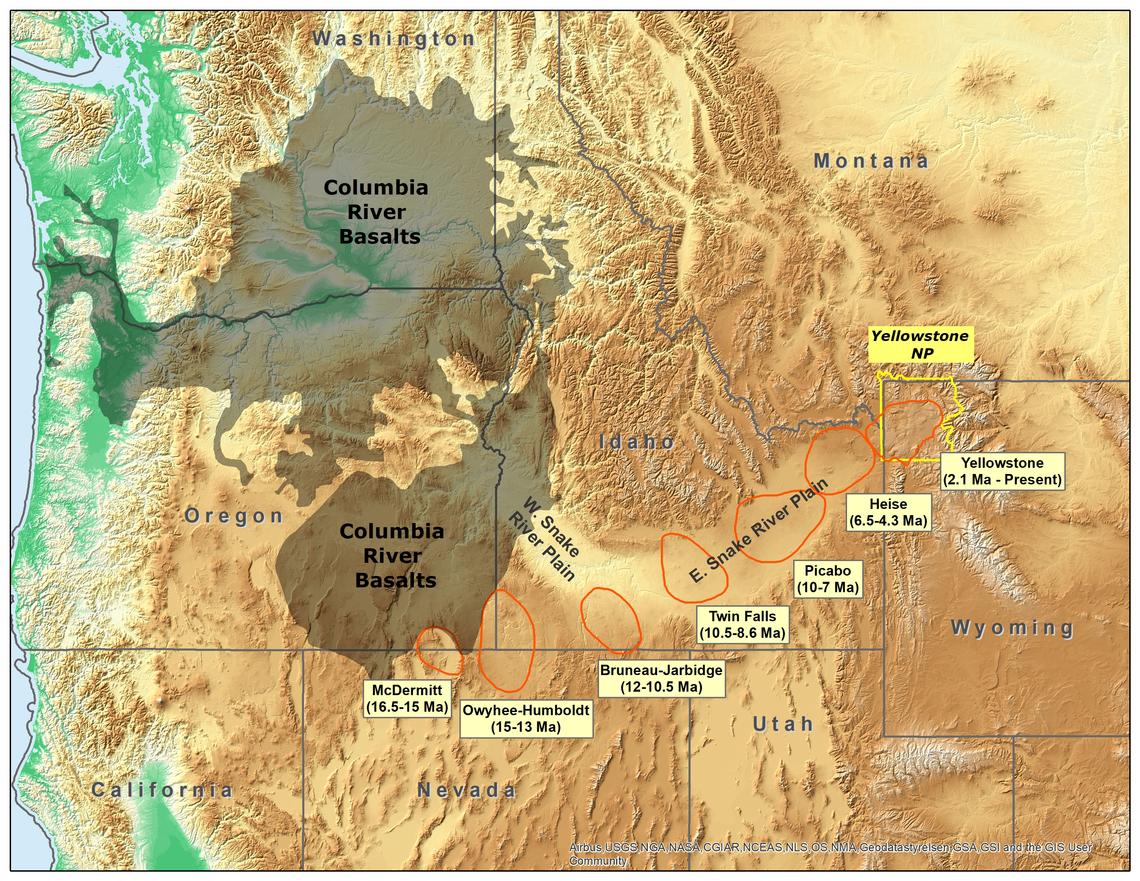

The Payette Section is a flat-lying area dominated by the drainage basin of the Payette River (a tributary of the Snake River with two major tributaries of its own: the North and South forks). The Snake River Plain is a low-lying, relatively flat area underlain by volcanic rocks. This low-lying area, formed from eruptions of the Yellowstone hot spot as the North American plate moved westward, forms an obvious feature on maps and satellite imagery.

Map showing the track of the Yellowstone Hot Spot, with the location of Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve marked. Map by Trista Thornberry-Ehrlich, Colorado State University (National Park Service, public domain).

Most of the features on the plain’s surface are lava flows and cinder cones, with a few volcanic domes.

Craters of the Moon National Monument encompasses three major lava fields, spanning about 1000 square kilometers (400 square miles) along Idaho’s Snake River Plain. The area’s volcanic features include volcanic domes, basaltic flows, lava tubes, open rifts, and ash flows. A lava field at Craters of the Moon National Monument, Idaho. Photograph by Neal Wellons (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

As one moves toward the western edge of the Snake River Plain, ash flows and tuff become more common.

Basin and Range

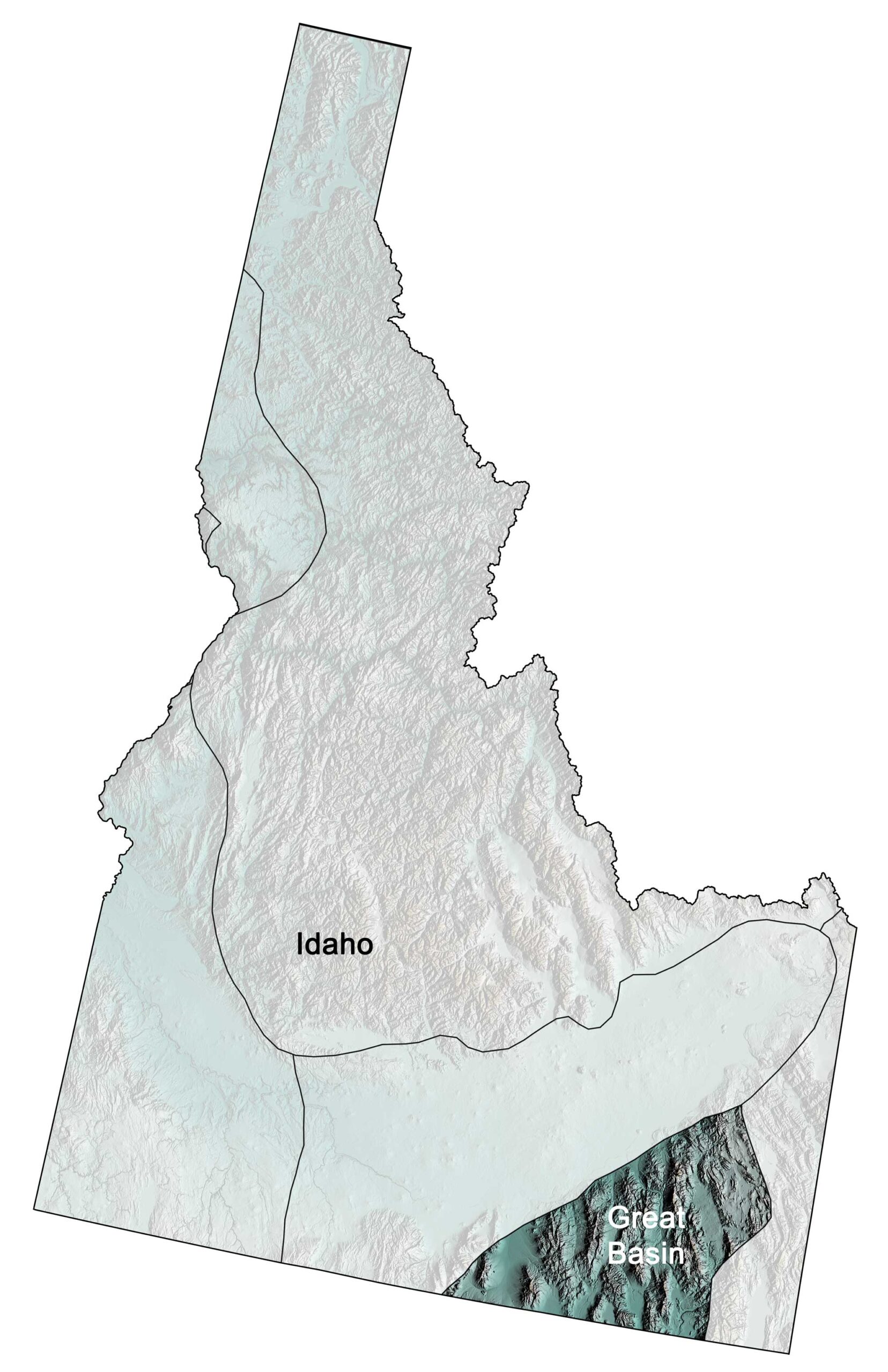

Physiographic subdivisions of the Basin and Range region of the northwest central United States; greens indicate lower elevation, browns higher elevation; black lines indicate physiographic boundaries of other provinces. Topographic data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM GL3) Global 90m (SRTM_GL3) (Farr, T. G., and M. Kobrick, 2000, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. AGU, 81:583-583.). Image created by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Only a small portion of the Basin and Range is found in the Northwest Central U.S., located in the southeastern corner of Idaho. The entire Basin and Range region stretches from Idaho through all of Nevada, southeastern California, and southeastern Oregon, and reaches as far as western Texas. The Basin and Range is characterized by rapid changes in elevation alternating from flat and dry basins to narrow and faulted mountains. This pattern of many parallel, north-south mountain ranges found throughout the region inspired geologist Clarence Dutton to famously observe that the topography of the Basin and Range appeared “like an army of caterpillars crawling northward.”

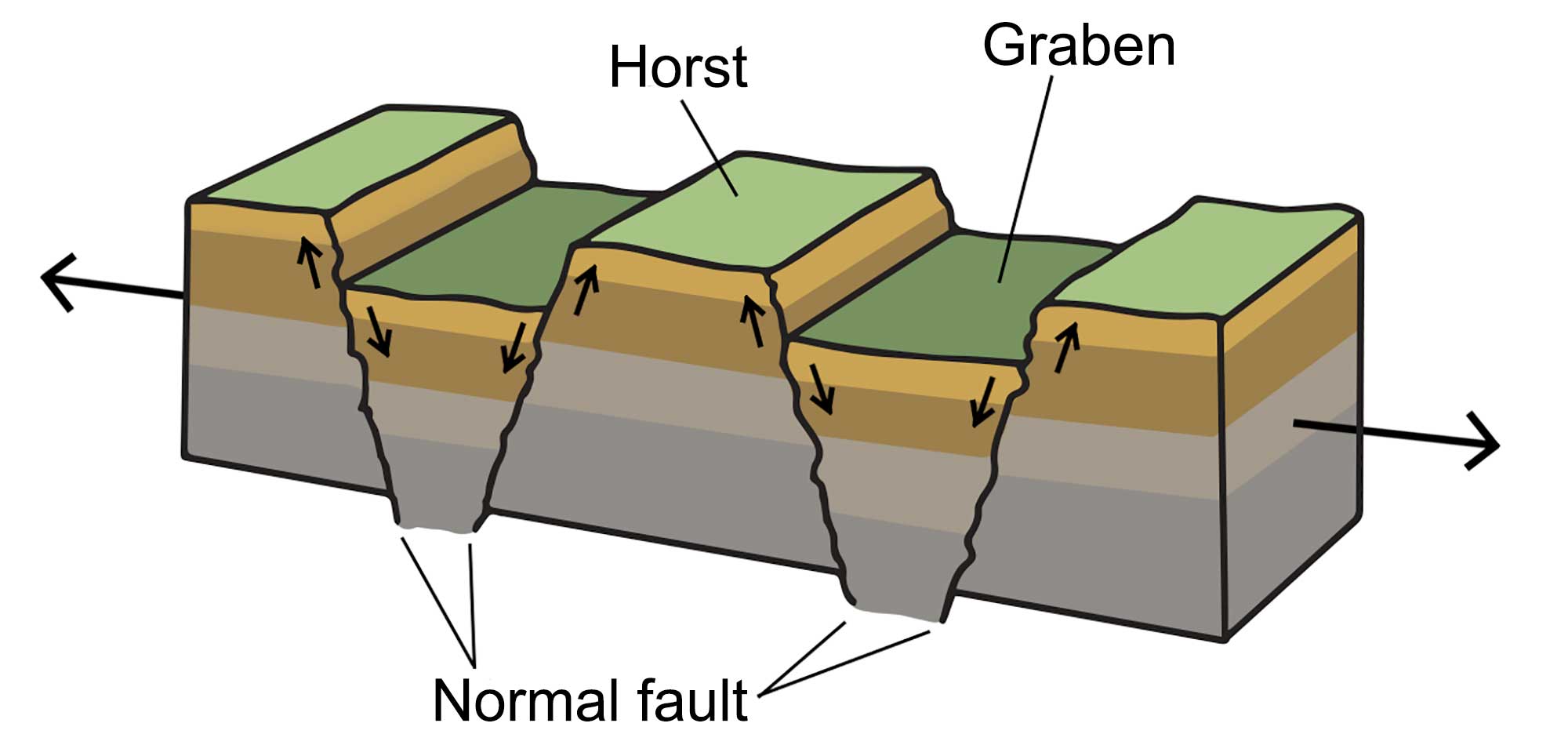

The formation of this topography is directly related to tectonic forces that led to crustal extension (pulling of the crust in opposite directions). After the Laramide Orogeny ended in the Paleogene, tectonic processes stretched and broke the crust, and the upward movement of magma weakened the lithosphere from underneath. Around 20 million years ago, the crust along the Basin and Range stretched, thinned, and faulted into some 400 mountain blocks. The pressure of the mantle below uplifted some blocks, creating elongated peaks and leaving the lower blocks below to form down-dropped valleys. The boundaries between the mountains and valleys are very sharp, both because of the straight faults between them and because many of those faults are still active. These peaks and valleys are also called horst and graben landscapes.

A horst and graben landscape occurs when the crust stretches, creating blocks of lithosphere that are uplifted at angled fault lines. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, modified for the Earth@Home project.

Such landscapes frequently appear in areas where crustal extension occurs, and the Basin and Range is often cited as a classic example thereof.

In the Basin and Range, the crust has been stretched by up to 100% of its original width. As a result of this extension, the average crustal thickness of the Basin and Range region is 30–35 kilometers (19–22 miles), compared with a worldwide average of around 40 kilometers (25 miles). In Idaho, the Basin and Range encompasses long, parallel mountain ranges, including the Bannock and Portneuf ranges.

The Portneuf Range, Bannock County, Idaho. Photograph by Charles (Chuck) Peterson (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

The crustal extension of the Basin and Range has increased strain and tension throughout the region, leading to a dynamic variety of active fault zones that create an abundance of earthquakes.