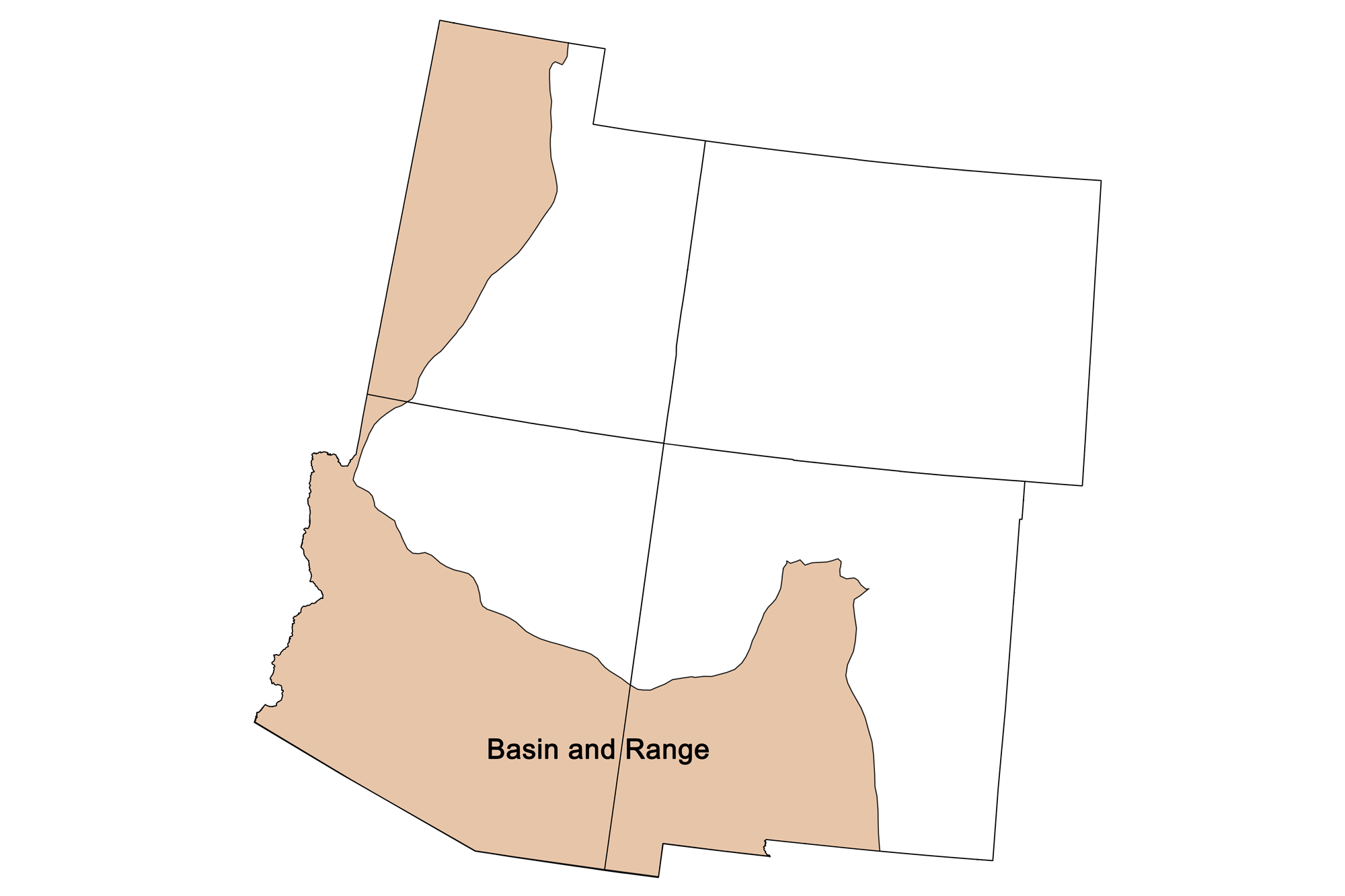

Snapshot: Overview of the mineral resources of the Basin and Range region of the southwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Metallic Resources; Non-Metallic Resources; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Mineral resources of the southwestern US" by Thomas R. Fisher, chapter 5 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated April 11, 2022.

Image above: Switchbacks in the Bingham Canyon Copper Mine in Utah. Photograph by "arbyreed" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

Overview

The Basin and Range region covers significant portions of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, as well as Nevada and parts of adjacent states. Around 30 million years ago in the early Oligocene, the North American plate began to override hot upwelling mantle, resulting in extensional forces that pulled the continental crust apart to form the region's distinctive "horst and graben" or “basin and range” structure of alternating, roughly north-south oriented valleys and mountain ranges. This extension influenced the shape of geological structures from earlier episodes of deformation, such as those of the Sevier Orogeny, which folded and faulted the region from the early Cretaceous (120 million years ago) through the Oligocene (52 million years ago). The events that formed the Basin and Range had a significant hand in emplacing the region's considerable mineral resources, which include major copper deposits as well as large quantities of gold, silver, lead, zinc, and molybdenum.

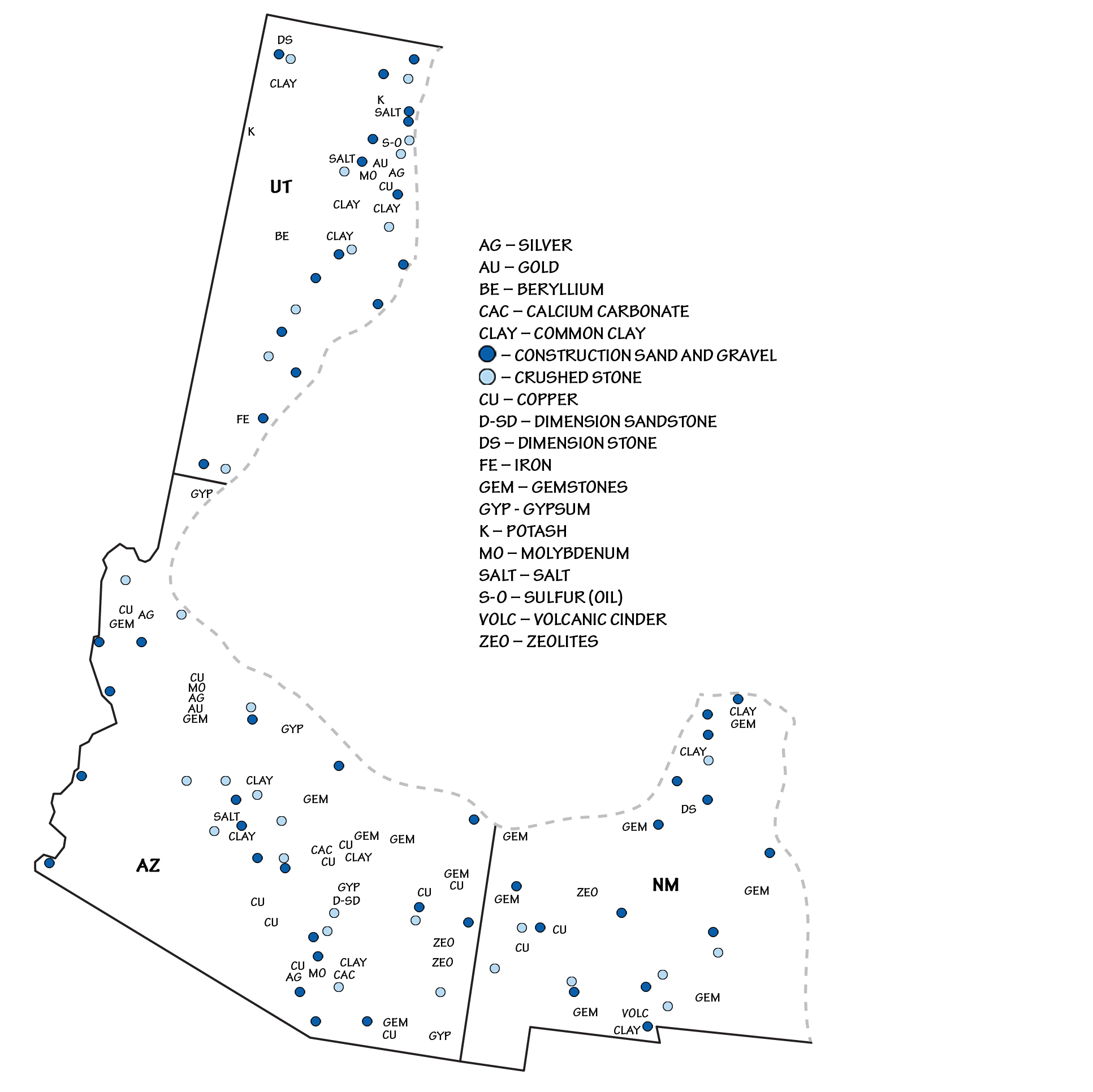

Principal mineral resources of the Basin and Range region. Image by Andrielle Swaby, adapted from USGS 2010-2011 and 2012-2013 State Minerals Yearbooks.

Some of the region's mineral deposits predate Cenozoic extension of the landscape. In western Utah, for example, deposits are often concentrated in semi-parallel northeast-trending belts, reflecting deep crustal structures or zones of weakness. The three belts in Utah are, north to south, the Uinta, the Tintic, and the Pioche belts. These structures cross physiographic region boundaries (e.g., from the Basin and Range into the Colorado Plateau), indicating they predate the development of these regions, and may date back to the Precambrian. Similar northeast-trending zones extend across other parts of the western US. These zones served as natural pathways for magmas and associated hydrothermal fluids to rise through the crust, from areas where heat from the hot, upwelling mantle melted the lower crust. This magmatic activity peaked from about 35 to 17 million years ago, and has continued at a decreasing rate nearly to the present day.

Metallic Resources

The Basin and Range is a hotbed of metallic ore deposits, especially along orogenic belts—the sites of mountain formation. The Sevier Orogenic Belt, a major geologic feature of the Basin and Range (and of the much larger Cordilleran Fold and Thrust Belt), marks the transition from the Colorado Plateau to the Basin and Range. Formed in the late Cretaceous and Paleogene, its structures provided fluid paths and hosts for mineral deposits all along this transition line. Economic deposits of gold, silver, copper, tungsten, and oil and gas are found within the margins of the Sevier Belt.

Thanks to the prolific amounts of copper ore found in Utah and Arizona, both states have taken copper as their state mineral. The Uinta, Tintic, and Pioche belts in Utah produce copper, gold, silver, lead, molybdenum, tungsten, uranium, and beryllium.

Gold and quartz from the Saw Tooth Mountains, near Salt Lake City, Utah. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

The Tintic Mining District, although largely defunct today, was an important source of silver, gold, copper, and bismuth during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Pioche Belt also contains the world's largest deposit of alunite, a sulfate mineral that is a source of both potassium and aluminum.

The Bingham Canyon deposit, located within the Uinta Belt, contains significant quantities of copper as well as considerable amount of gold and other minerals. Kennecott Copper's Bingham Canyon Mine, near Salt Lake City, Utah, is one of the largest open pit mines in the world and produces 25% of the US domestic copper supply.

Bingham Canyon Cooper Mine in Utah. Photograph by Doc Searls (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

So large that it is visible from space, the mine is about a kilometer (over half a mile) deep and produces 408,000 metric tons (450,000 tons) of material per day. Since extraction began in 1863, the mine has produced over 15.4 billion kilograms (17 million tons) of copper, 715,000 kilograms (23 million troy ounces) of gold, 5.9 million kilograms (190 million troy ounces) of silver, and 317 million kilograms (850 million pounds) of molybdenum. This quantity exceeds all of the metals ever produced from the famous Comstock Lode, the Klondike, and the California Gold Rush combined.

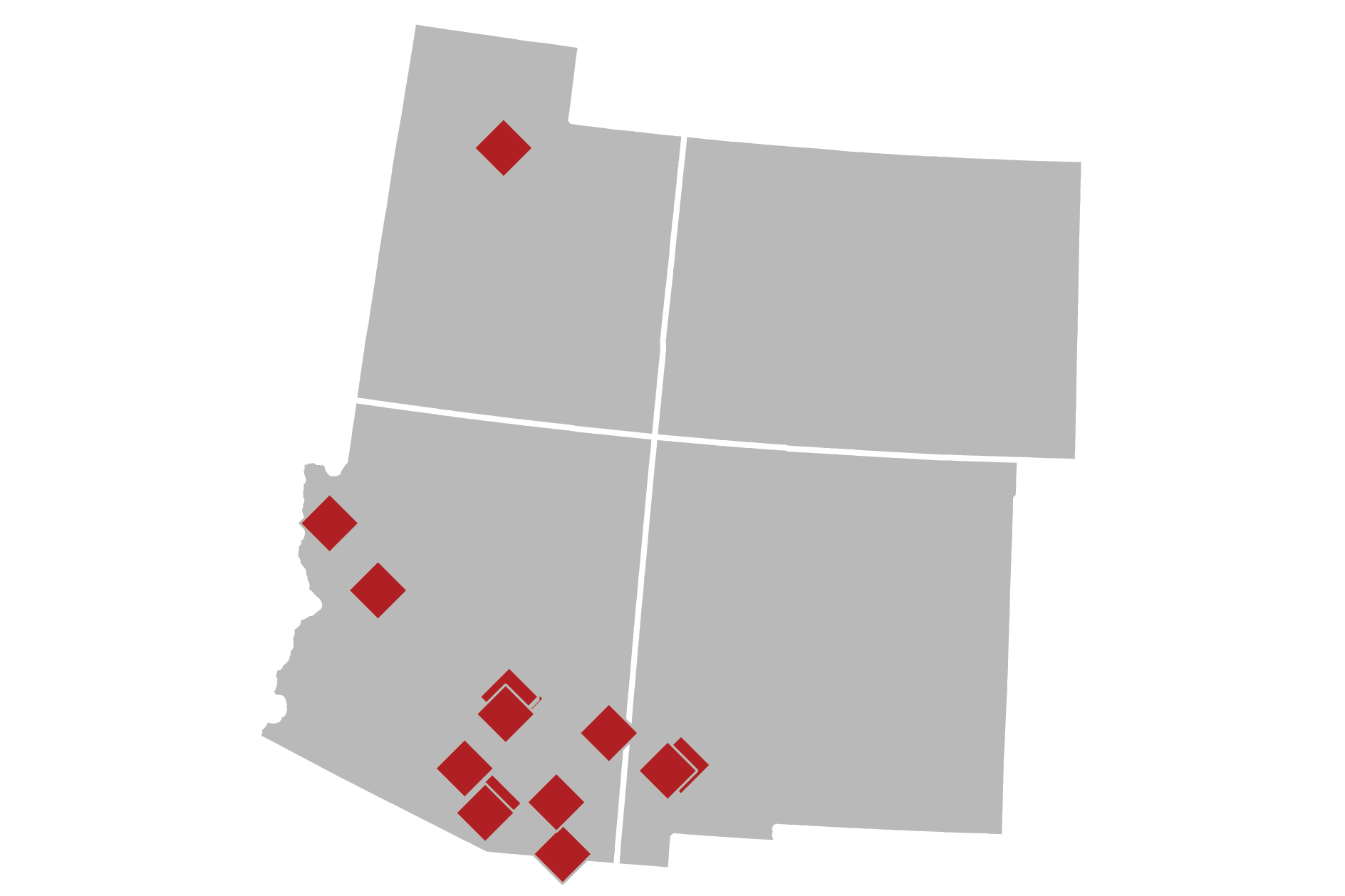

Southeastern Arizona is dominated by porphyry copper and associated lead, zinc, gold, and silver deposits in granitic rocks. These deposits were emplaced between 75 and 55 million years ago, predating the development of the Basin and Range's modern structure. Metal ores along the state's western side are dominated by gold deposits in 25- to 15-million-year-old volcanic rocks. Although gold was the first mineral to be mined in Arizona, the state quickly became known for its copper, and by 1910 it was the top copper-producing state in the nation—a title it still holds today. Enormous mines in Arizona's southeastern corner account for over 60% of US copper production; the Morenci Mine in Greenlee County has reserves estimated at 2.9 billion metric tons (3.2 billion tons) of ore. There is so much copper in Arizona that its nickname is “the Copper State.”

Distribution of copper mines in the Southwestern US. Image by "Kbh3rd" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license; image modified from original).

Sample of native copper from the Morenci Mine in Greenlee County, Arizona. Photograph by "Tjflex2" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

The Rio Grande Rift, which extends from Mexico into Colorado and the southern Rocky Mountains, was formed by extensional forces that pulled the continental crust apart in an east-west direction to form the Rio Grande Valley. Like the rest of the Basin and Range, ore in the Rio Grande Rift was deposited from hydrothermal solutions associated with magmatic bodies that rose after heat from the hot upwelling mantle melted them near the lower crust. The Rift is known for its production of copper, gold, silver, lead, zinc, manganese, and a host of other minerals, as well as molybdenum from the Questa Mine near Red River. New Mexico is currently the nation's number three copper-producing state, with two large open pit mines in Grant County: the Tyrone mine and the Santa Rita mine. Together, these mines have produced as much as 113 million kilograms (249 million pounds) of copper, 370,000 grams (13,000 ounces) of gold, and 5.9 million grams (209,000 ounces) of silver per year. The Santa Rita mine is the oldest copper mine in the western US, and was used by Spaniards as early as 1800.

The Rio Grande Rift is also home to a great number of rare earth elements vital to developing technologies, including thorium, lanthanum, yttrium, and the cerium-rich mineral bastnasite. These valuable metals are useful in a range of technological industries, with applications ranging from manufacturing processes to use in electronics such as HDTVs, computers, hybrid and electric vehicles, solar and wind power generators, compact fluorescent lamps, and LEDs.

Non-Metallic Resources

Gemstones and precious stones

The Southwestern US, particularly the Basin and Range, is especially wellknown for its gemstones and precious stones. This region, with its combination of faulted sedimentary rocks and intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks, provides a rich set of geochemical environments for a diversity of minerals to grow along fracture surfaces, in cavities, and within the igneous bodies themselves. Thus, while the individual minerals form under specific conditions (e.g., chemistry, heat, pressure, and space for growth), the region has a sufficiently broad mix of conditions to allow many different precious gems to form. Gems and precious stones found in the Basin and Range include turquoise, peridot, amethyst, garnet, jade, opal, beryl, topaz, and many others.

The Basin and Range is especially famous for turquoise; it is the state gemstone of both Arizona and New Mexico.

Interactive 3D model: A Navajo band bracelet (ca. 1940s-1950s) with turquoise stones. Model by California Academy of Sciences (Sketchfab).

This copper-bearing precious mineral is found in areas with substantial copper deposits, and is sometimes removed during copper mining. In the Basin and Range, turquoise is found where copper sulfide deposits weather around certain intrusive igneous rocks. It was one of the first gems to be mined, generally for use in jewelry or sculpture, with extraction dating back over one thousand years. Arizona and parts of New Mexico are among the largest turquoise producing areas of the US, and Arizona still produces the most valuable turquoise in the country, though many mines there have now been depleted. The precious stones azurite and malachite, spectacular blue and green by-products of copper ore weathering, are also common in this area and highly prized by collectors.

Interactive 3D model. Large rock at Tohono Chul Park in Tuscon, AZ with azurite and malachite on its surface. Model by Abby Crawford (Sketchfab).

Topaz and beryl form in the fractures and cavities of silica-rich igneous rocks such as granite and rhyolite. Topaz is hard (Mohs scale 8) and resistant to erosion, often weathering out of its matrix to be found as pebbles in streams. In Utah, where it is the state gem, topaz can be collected from the rhyolites of the Thomas Range, specifically at Topaz Mountain. The mineral is fairly rare, as it contains fluorine, which does not occur frequently in quantities sufficient for mineral formation. Other gemstones can be found at Topaz Mountain, including red beryl. This rare mineral contains the element beryllium, and is colored red due to trace amounts of manganese.

Salt

The Basin and Range in Utah is known for the expansive Bonneville Salt Flats, a 12,000-hectare (30,000-acre) salt pan along the western margin of the Great Salt Lake Basin.

The Bonneville Salt Flats. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Salt deposits on the surface of the Bonneville Salt Flats. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

The salt crust is as much as 1.5 meters (5 feet) thick toward the center of the salt flats, and its total volume has been estimated at 133 million metric tons (147 million tons) of salt. This massive, salty expanse is the evaporative remnant of Pleistocene Lake Bonneville—a huge pluvial lake that once covered much of Utah. The salt is mined at Sevier Lake and the Great Salt Lake, where it is recovered for industrial and commercial use via evaporation in man-made ponds. The salt beds and brines of the Great Salt Lake produce salt, potassium sulfate, and magnesium chloride, and are reported to contain lithium chloride. A potash development project is also underway at Sevier Lake.

Volcanic materials

Volcanic deposits associated with Basin and Range tectonics provide industrial minerals such as volcanic cinder and pumice, as well as clays from weathered volcanic ash. The combination of volcanic glass and ash with saline and alkaline water in rift basins gave rise to natural zeolites, which are mined in New Mexico and Arizona. These porous alumino-silicate minerals have cation exchange properties that can transform hard water into soft water.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life: Minerals (collection of 3D models on Sketchfab): https://skfb.ly/6WxTo

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals: https://earthathome.org/de/minerals/