Snapshot: Overview of the mineral resources of the Colorado Plateau region of the southwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Metallic Resources; Non-Metallic Resources; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Mineral resources of the southwestern US" by Thomas R. Fisher, chapter 5 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated April 11, 2022.

Image above: Slabs of Arizona Flagstone in a supply yard near Ash Fork, Arizona. Photograph by W. Lauzon (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

Overview

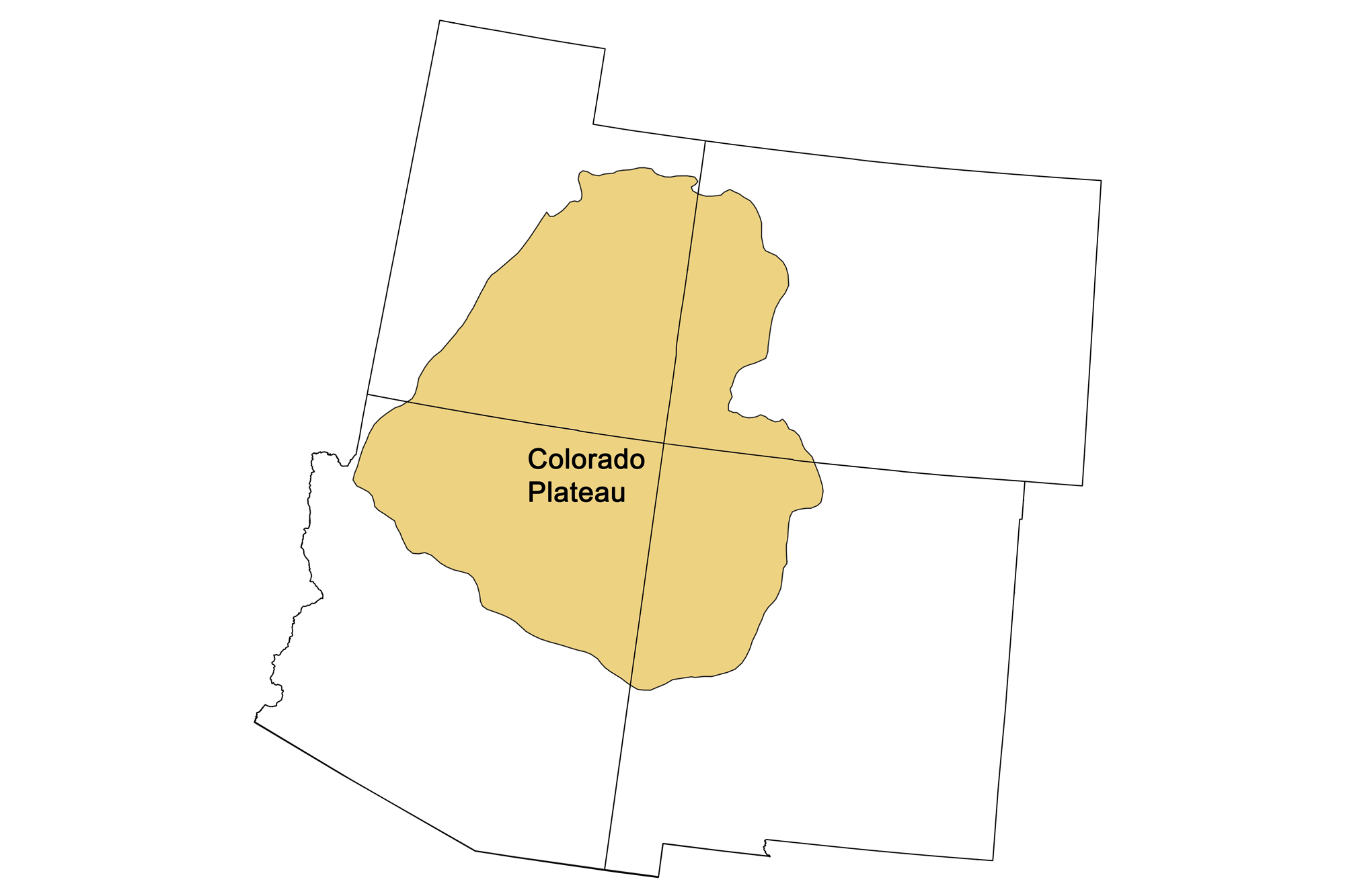

An area about the size of the state of Montana, the Colorado Plateau is an enigmatic block of continental crust some 45 kilometers (28 miles) thick that has remained relatively stable for over 500 million years. It began rising around 100 million years ago, rose further in the Eocene (56-33 million years ago), and then once more during an epeirogenic event approximately 8 to 6 million years ago. The Grand Canyon began to incise into the Plateau beginning in the Eocene, eventually cutting down far enough to expose 500 million years of horizontal sedimentary strata and underlying tilted metamorphic and igneous Precambrian basement rocks. There have been no major magmatic events in the Colorado Plateau, so the metallic resources found there are relatively minor, although a few younger igneous and volcanic intrusive rocks were important to metal emplacement. Most of the Plateau's mineral ore deposits have sedimentary origins and are associated with the region's depositional basins.

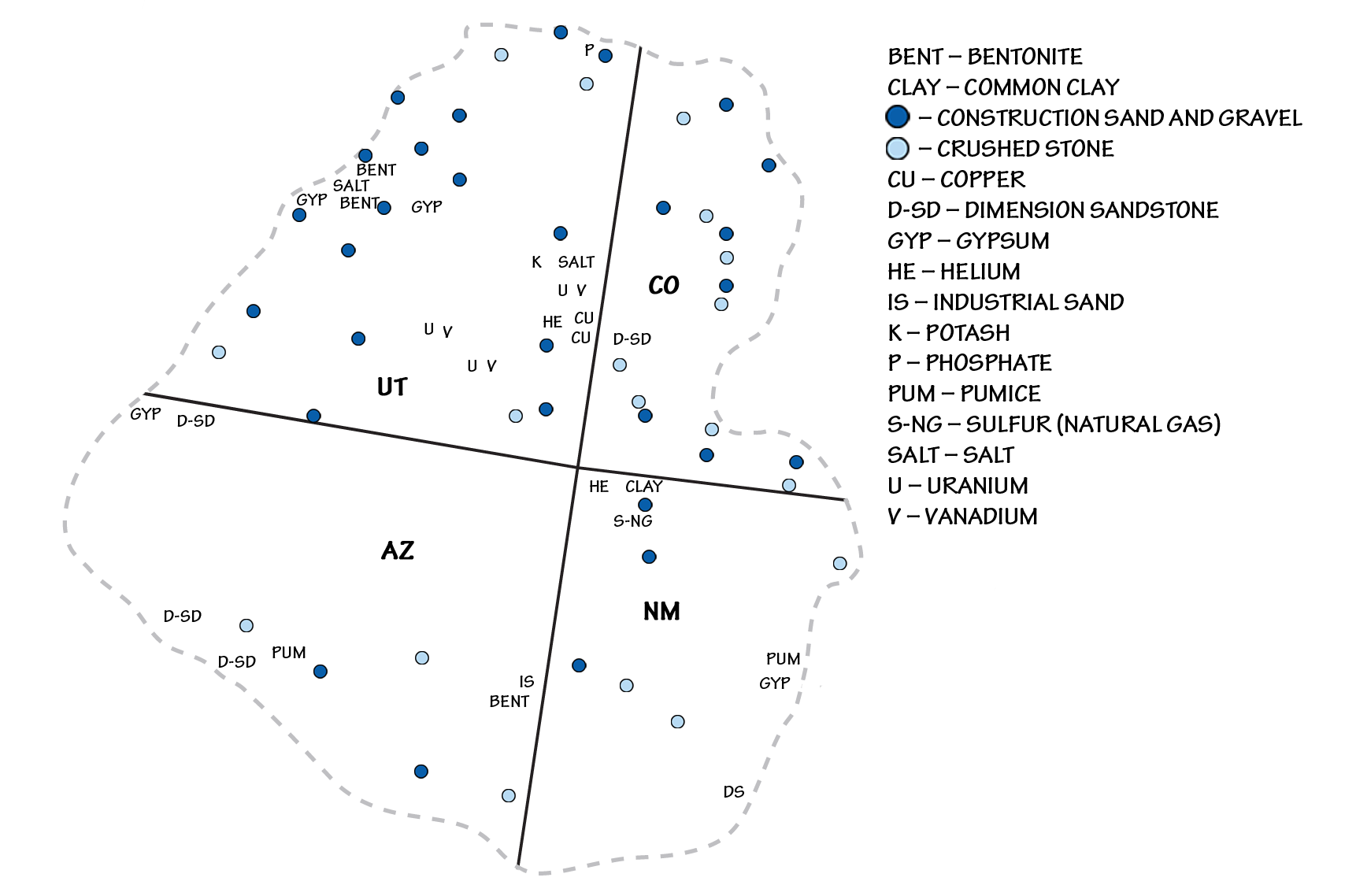

Principal mineral resources of the Colorado Plateau region. Map by Andrielle Swaby, adapted from USGS 2010-2011 and 2012-2013 State Minerals Yearbooks.

Metallic Resources

Uranium

Although the US has perennially imported over 90% of its uranium ore from foreign sources, the Paradox Basin in the Colorado Plateau is seen as an important source for US uranium supplies, which are mined for use in nuclear energy.

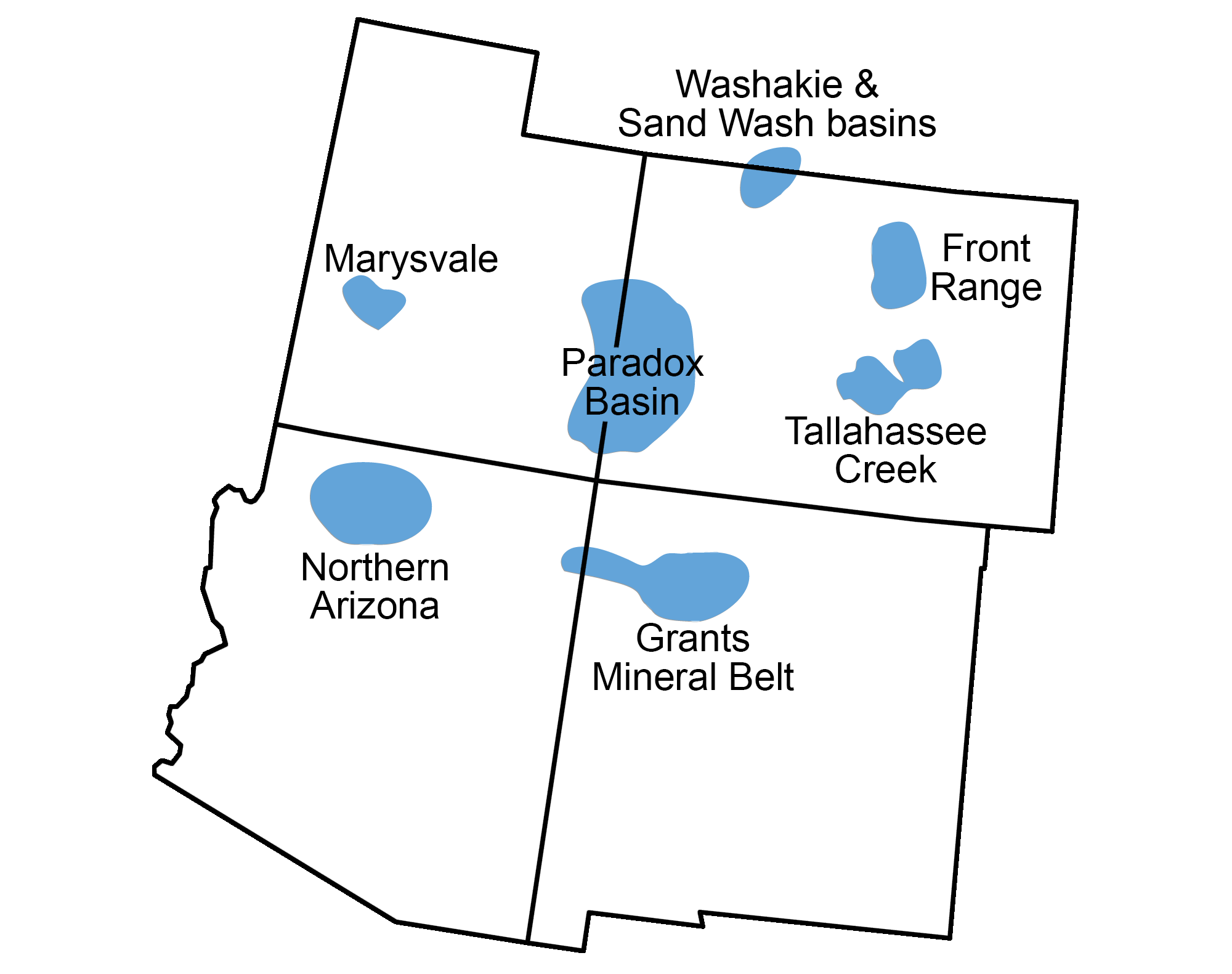

Distribution of uranium deposits in the southwestern United States. Map by Andrielle Swaby, adapted from image by the U.S. Energy Information Administration and modified for the Earth@Home project.

Uranium mining, Nucla, west-central Colorado, 1972. Photo by Bill Gillette, DOCUMERICA (U.S. National Archives Identifier 543775, unrestricted use).

These uranium deposits occur largely as “roll-front” deposits, in which groundwater leaches uranium from the source rock (usually igneous or metamorphic basement rock or volcanic ash deposits), and carries it through a porous and permeable rock, typically sandstone or conglomerate. Uranium oxide minerals are precipitated when the uranium-bearing groundwater is reduced by contact with organic materials within the rock. The uranium minerals carnotite and coffinite account for the majority of the ores in these deposits. Vanadium minerals such as corvurite and doloresite are also found with these ores. Most commonly, the region's uranium- and vanadium-bearing minerals are hosted in fluvial and lacustrine sandstones and limestones of the Triassic Chinle, Jurassic Morrison and Todilto, and Cretaceous Dakota formations. Lithium, a major component of high-tech batteries, is recovered from the Paradox Basin.

Of the US states, New Mexico currently ranks second in uranium resources after Wyoming. Most of the state's deposits are located in the Grants Mineral Belt to the northwest, although no mining has taken place there since 2002. Other major uranium deposits are found near Moab, Utah in the Paradox Basin; on the San Rafael Swell in central Utah; and near Uravan, Colorado, where the last uranium mine was closed in 2009 due to a drop in uranium prices. New mines are being planned for the Colorado Plateau should demand increase for nuclear power.

Copper

Similar to uranium deposits, sediment-hosted stratiform copper deposits are found in the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous rocks of the Plateau, mainly in Utah's Paradox Basin. The Salt and Lisbon valleys near Moab, Utah host several copper deposits in porous and permeable fluvial sandstones. These deposits formed from warm saline and copper-bearing fluids that deposited copper minerals, such as chalcocite, malachite, and azurite.

Gold

The only gold deposits reported on the Colorado Plateau are of placer origin. These are found largely in the Abajo, La Sal, and Henry mountains of Utah and along the nearby Green, Colorado, and San Juan rivers and their tributaries. The Abajo, La Sal, and Henry mountains are all laccolithic intrusions of relatively late Oligocene to early Miocene in age (29 to 22 million years ago). The region's placer gold was likely concentrated by the erosion of these intrusive rocks.

Non-Metallic Resources

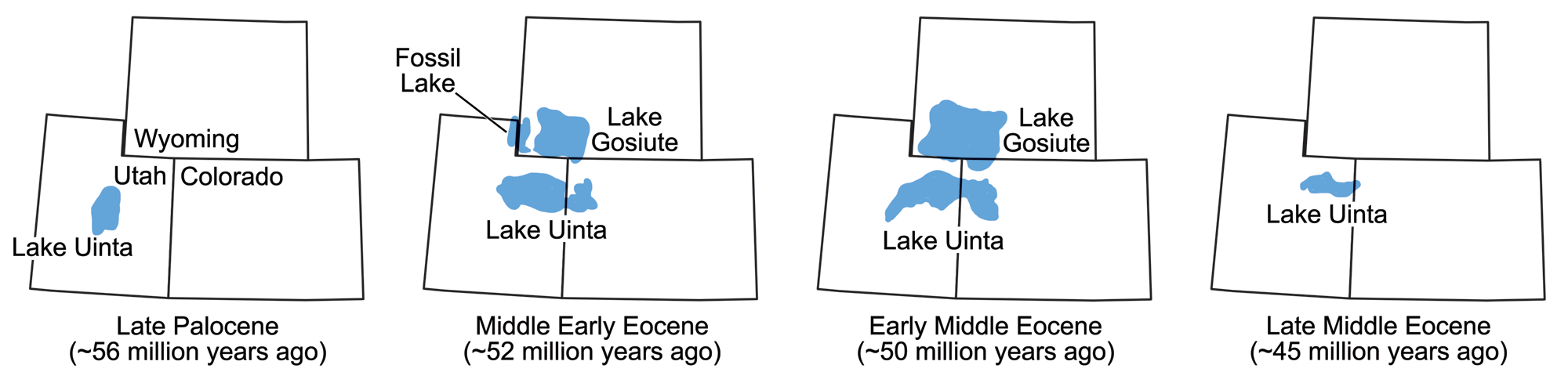

In Colorado and Utah, the Colorado Plateau hosts the Eocene Green River Formation, which represents an almost continuous six-million-year record of very thinly bedded lacustrine (lake) sediments, including salt deposits from times of high salinity. The formation is restricted to the Green River basins of Wyoming, the Uinta and Washakie basins of Utah, and the Piceance Basin of Colorado.

The size and location of various lakes in which the Green River Formation sediments were deposited during the Eocene epoch. Maps modified from maps by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, after figure 3 in L. Grande (2013) The Lost World of Fossil Lake.

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate)

These basins contain the largest known deposit of the mineral nahcolite (sodium bicarbonate) in the world. Sodium bicarbonate, commonly known as baking soda, is used in cooking, fire extinguishers, “green” bio-pesticides, hygiene products, cleaning agents, and numerous medical applications.

Trona

The Green River Formation also contains the world's largest deposit of trona, a non-marine evaporite mineral that is mined as a primary source of sodium carbonate. Trona is a common food additive and water softener, and it also has applications in the manufacturing of paper, textiles, glass, and detergents.

Halite, gypsum, potash, and other salts

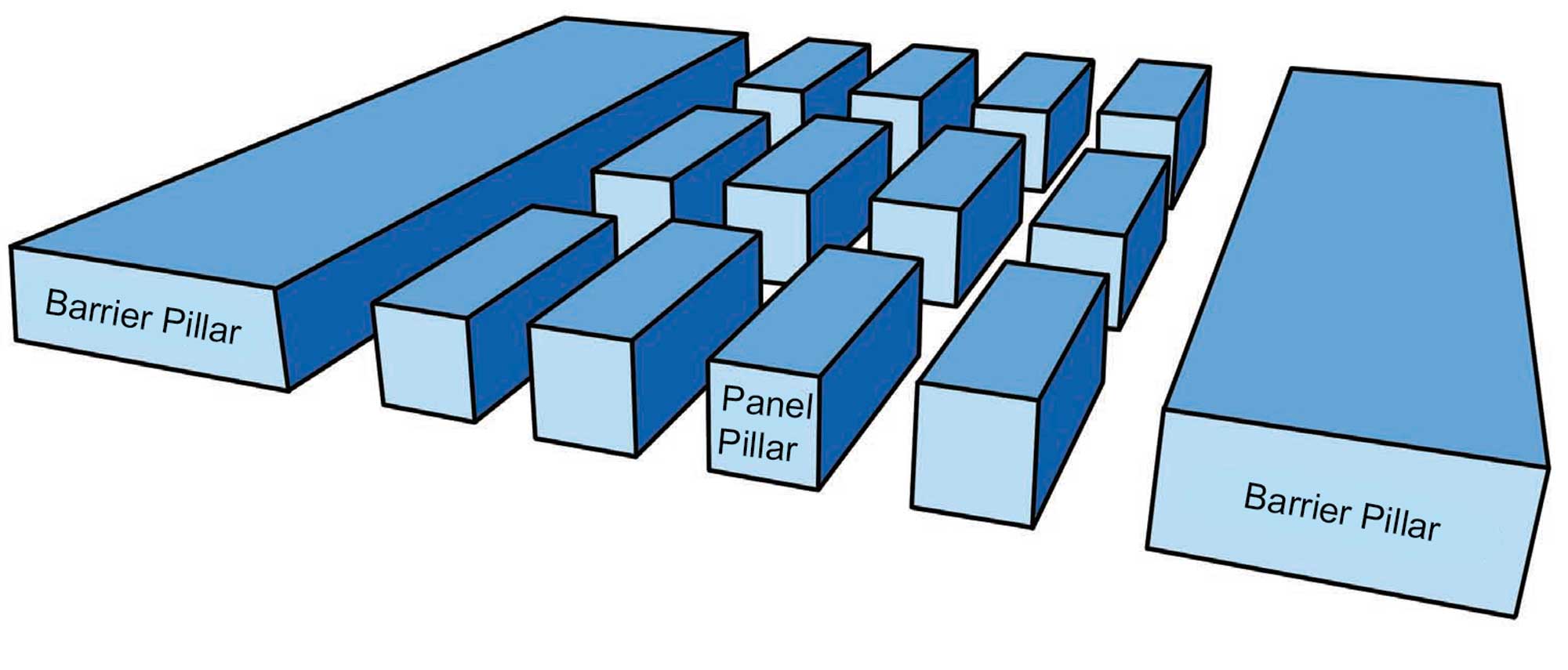

Thick repetitive sequences of salts formed by the evaporation of shallow seas are found in the Pennsylvanian Paradox Formation. Great amounts of these evaporites are recovered from deep beneath the surface of the Paradox Basin in Utah and Colorado, where the formation yields potash and other salts such as magnesium chloride, sylvite, carnalite, and halite (rock salt). These evaporite minerals are mined in two different ways. When deposited in thick beds, salt can be excavated by mechanically carving and blasting it out. This method, called “room and pillar” mining, usually requires that pillars of salt be left at regular intervals to prevent the mine from collapsing.

In pillar and room mining, the mine is divided up into smaller areas called "panels." Groups of panels are separated from one another by extra-large (barrier) pillars that are designed to prevent total mine collapse in the event of the failure of one or more regular-sized (panel) pillars. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, adapted from image by "Swinsto101" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license) and modified for the Earth@Home project.

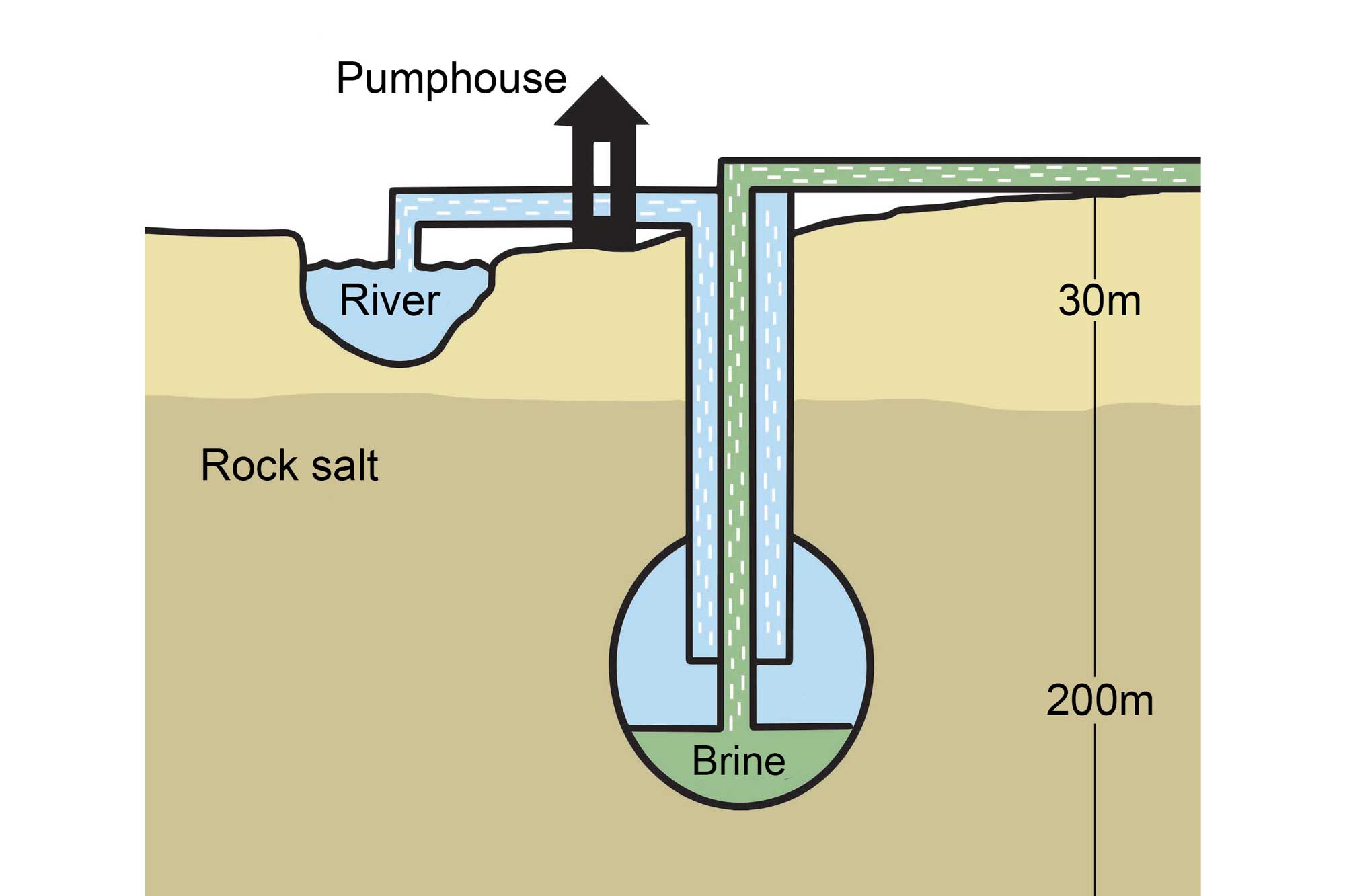

Another method, called solution mining, involves drilling a well into a layer of salt. In some cases, the salt exists as part of a brine that can then be pumped to the surface, where the water is then removed, leaving the salt behind. In others, fresh water is pumped down to dissolve the salt, and the solution is brought back to the surface where the salt is removed.

An example of solution mining that involves the pumping of fresh water through a borehole drilled into a subterranean salt deposit. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, adapted from image by the Salt Association and modified for the Earth@Home project.

Most evaporites in the Colorado Plateau are extracted by solution mining. Gypsum has also been mined in large quantities from the Paradox Formation and several Jurassic-age formations.

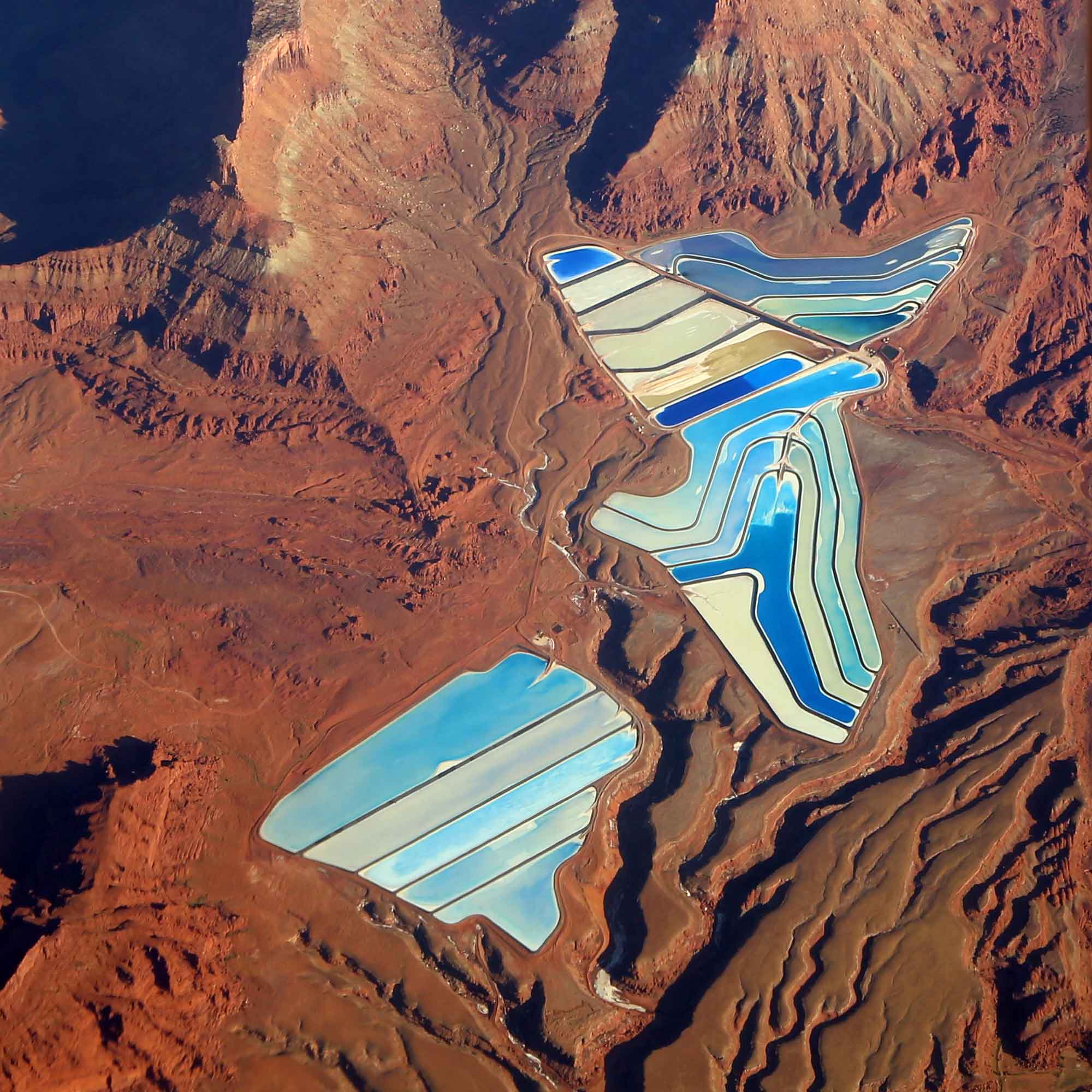

The Paradox Basin salt beds represent a massive resource of potash, a name used for a variety of salts containing potassium, with mined potash being primarily potassium chloride. The USGS has estimated that the basin contains up to 1.8 billion metric tons (2 billion tons) of the mineral, the majority of which is used as fertilizer. Today, an increasing amount of potash is being used in a variety of other ways: for water softening, for snow melting, in a variety of industrial processes, as a medicine, and to produce potassium carbonate. Intrepid Potash, Inc., a Denver-based corporation, is the largest producer of potash in the United States and operates three mines in the Southwest, with the primary site located west of Moab, Utah.

Potash evaporation ponds at the Intrepid Potash mine near Moab, Utah. The Colorado River is located to the right of the ponds, which are dyed blue to enhance evaporation. Photograph by Doc Searls (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

Bentonite

Bentonite is currently mined in the Southwest, and is often found interbedded with volcanic ash. Bentonites are formed from weathered volcanic ash and glass, and are used in a variety of water-absorbing applications such as drilling mud and cat litter. In the Colorado Plateau, bentonites are found in Pliocene beds in Chito, Arizona as well as in the Triassic Chinle and Morrison formations.

Construction materials

Large quantities of sand, gravel, and crushed stone are locally quarried for use as construction aggregate, which is used to strengthen concrete, make blacktop, produce building materials, and as road and dam foundations. Many of these are gathered from old stream terrace deposits, deposited after ancient streams eroded the Rocky Mountains to the north and carried gravels made up of quartz and quartzite, limestone, sandstone, and harder igneous rocks. Some types of sand are quartz rich, which makes them useful for other industrial purposes. This “industrial sand” is used in sandblasting, filtering, and the manufacturing of glass.

Dimension stone, used for buildings, monuments, curbing and facing, is also quarried around the Plateau's rim. Ash Fork, in Yavapai County, Arizona, is the center of production for Arizona Flagstone, a warm-colored dimension sandstone dominated by quartz and silica.

Slabs of Arizona Flagstone in a supply yard near Ash Fork, Arizona. Photograph by W. Lauzon (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

Ancient sedimentation patterns favored the placement of widespread fossil fuel resources in the Colorado Plateau. Processing plants in Utah and New Mexico recover helium gas, an important byproduct of natural gas extraction.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life: Minerals (collection of 3D models on Sketchfab): https://skfb.ly/6WxTo

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals: https://earthathome.org/de/minerals/