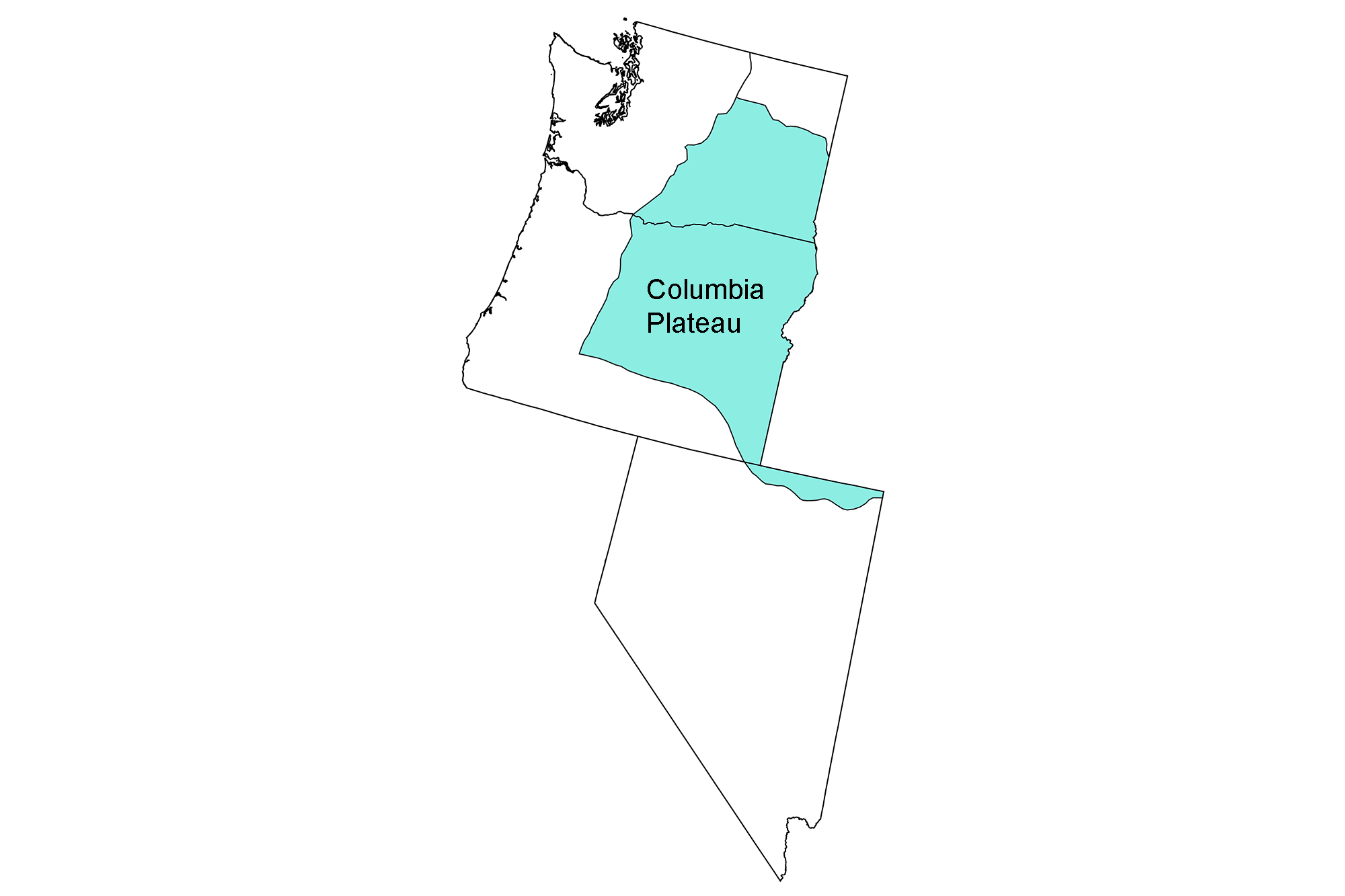

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Columbia Plateau region of the western United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Mesozoic fossils; Cenozoic fossils; John Day Fossil Beds; Eocene Clarno Formation; Oligocene John Day Formation; Miocene Mascall Formation; Miocene Rattlesnake Formation; Quaternary fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Western US" by Brendan M. Anderson, Alexandra Moore, Gary Lewis, and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated September 1, 2022.

Image above: Skull of an extinct horse (Miohippus), John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Photo by U.S. National Park Service (public domain).

Paleozoic fossils

The fossil brachiopod Titanaria is found in Mississippian rocks in northern California (Baird Shale, Shasta County) and central Oregon (Coffee Creek Formation) and is among the largest brachiopods in the world. Titanaria's shell reached widths (along the hinge line) of more than 35 centimeters (14 inches).

The brachiopod Titanaria from the Mississippian of Oregon. Specimen from the U.S. National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian), photographed by Wade Greenberg-Brand. Originally published inThe Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Western US.

Mesozoic fossils

During the Jurassic and part of the Cretaceous, ammonoid cephalopods and bivalves were abundant and diverse in the shallow sea that covered this region. Vertebrate fossils are found occasionally, including sea crocodiles and pterosaurs.

Bone fragments (left, part of a humerus, or upper arm bone; right, part of a vertebra) of Zoneait nargorum, a so-called "sea crocodile" (that is not closely related to modern crocodiles) from the Jurassic Snowshoe Formation of Oregon. Photo of USNM PAL 256441 and USNM PAL 256443 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

The pterosaur Bennettazhia oregonesnis from the Cretaceous of Oregon. Left: An arm bone (humerus) and a vertebra. Photo of USNM V 11925 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain). Right: Silhouette reconstructing the possible appearance of Bennettazhia and the position of the bones in the left image in the skeleton. Illustration by Dean Falk Schnabel (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Cenozoic fossils

Several sites in Oregon and Washington preserve abundant Cenozoic terrestrial fossils, especially plants and mammals, as a result of widespread volcanic activity in the area. During the Neogene, the Columbia Plateau was covered in large volcanic outflows of flood basalt. These outflows are associated with the same hot spot that now heats Yellowstone National Park. Some of these lava flows overran forests, leaving behind empty molds of trees.

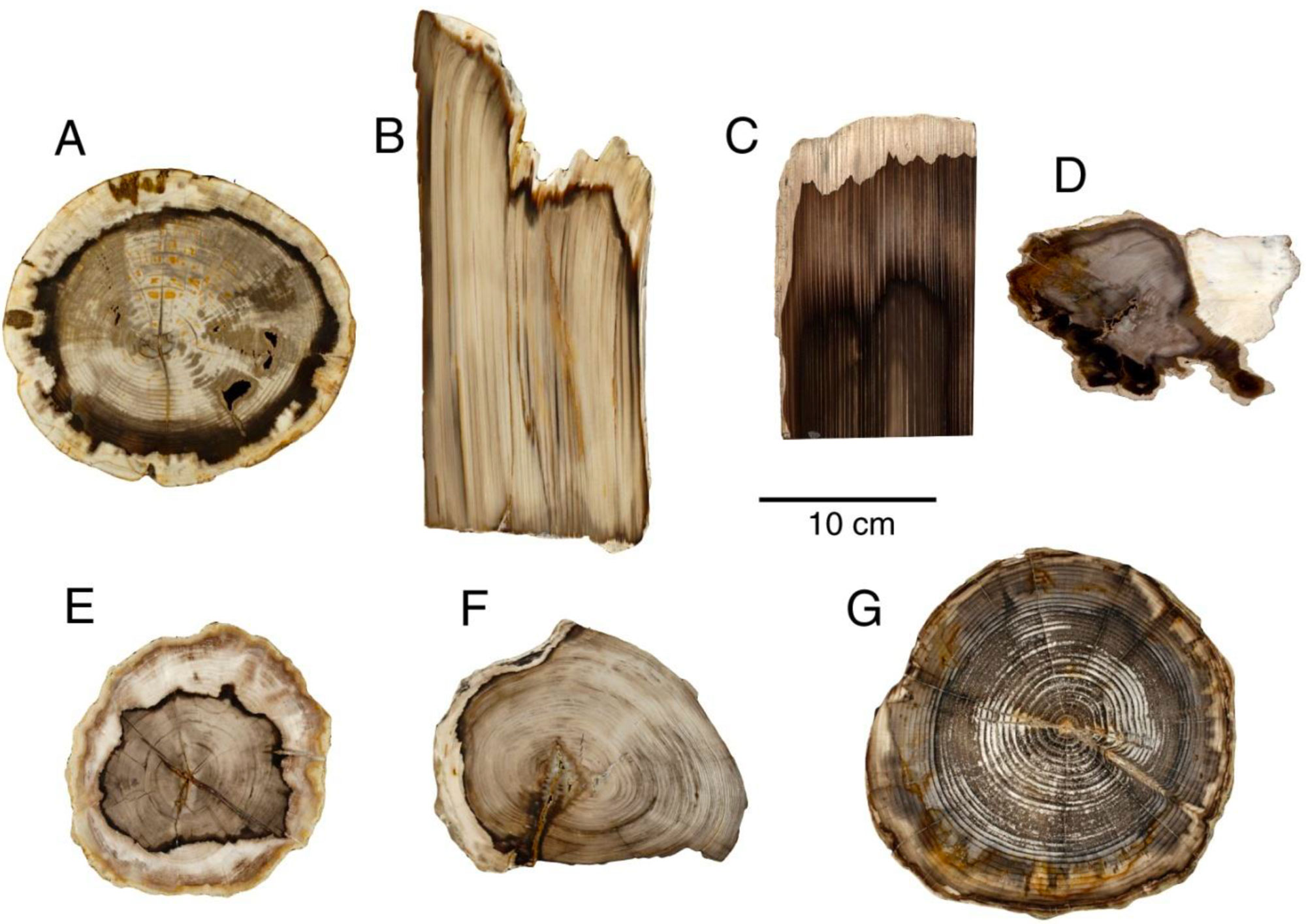

At some localities, such as Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park in Washington, petrified (permineralized) wood has been preserved either by burial within lake sediments or in volcanic mudflows. Examples of petrified wood types preserved in this region include ginkgo, conifers (pine, Douglas fir, bald-cypress-like), and many angiosperms (sycamore, sweet gum, alder, elm, tupelo, hickory, oak, and cherry).

Middle Miocene petrified logs at Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park near Vantage, Washington. Photo by Sean O'Neill (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Petrified wood from the middle Miocene of Washington. A. Ash-like wood (Fraxinus), Ginkgo Petrified Forest. B. Conifer wood, cypress family (Cupressaceae), Saddle Mountain. C, D. Conifer wood, Umtanum Canyon. E. Wood of a member of the walnut family (Rhysocaryoxylon, Juglandaceae), Yakima Ridge Terrace Heights. F. Conifer wood, cypress family (Taxodioxylon, Cupressaceae), Saddle Mountain. G. Conifer wood, pine family (Piceoxylon, Pinaceae), Ginkgo Petrified Forest. Source: Figure 16 from Mustoe and Dilhoff (2022) Minerals 12(2) 131 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

John Day Fossil Beds

The Eocene to Miocene Clarno, John Day, and Mascall formations are collectively known as the John Day Fossil Beds. They span over 40 million years and can be best seen in and around John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in Wheeler and Grant Counties in north-central Oregon.

Eocene Clarno Formation

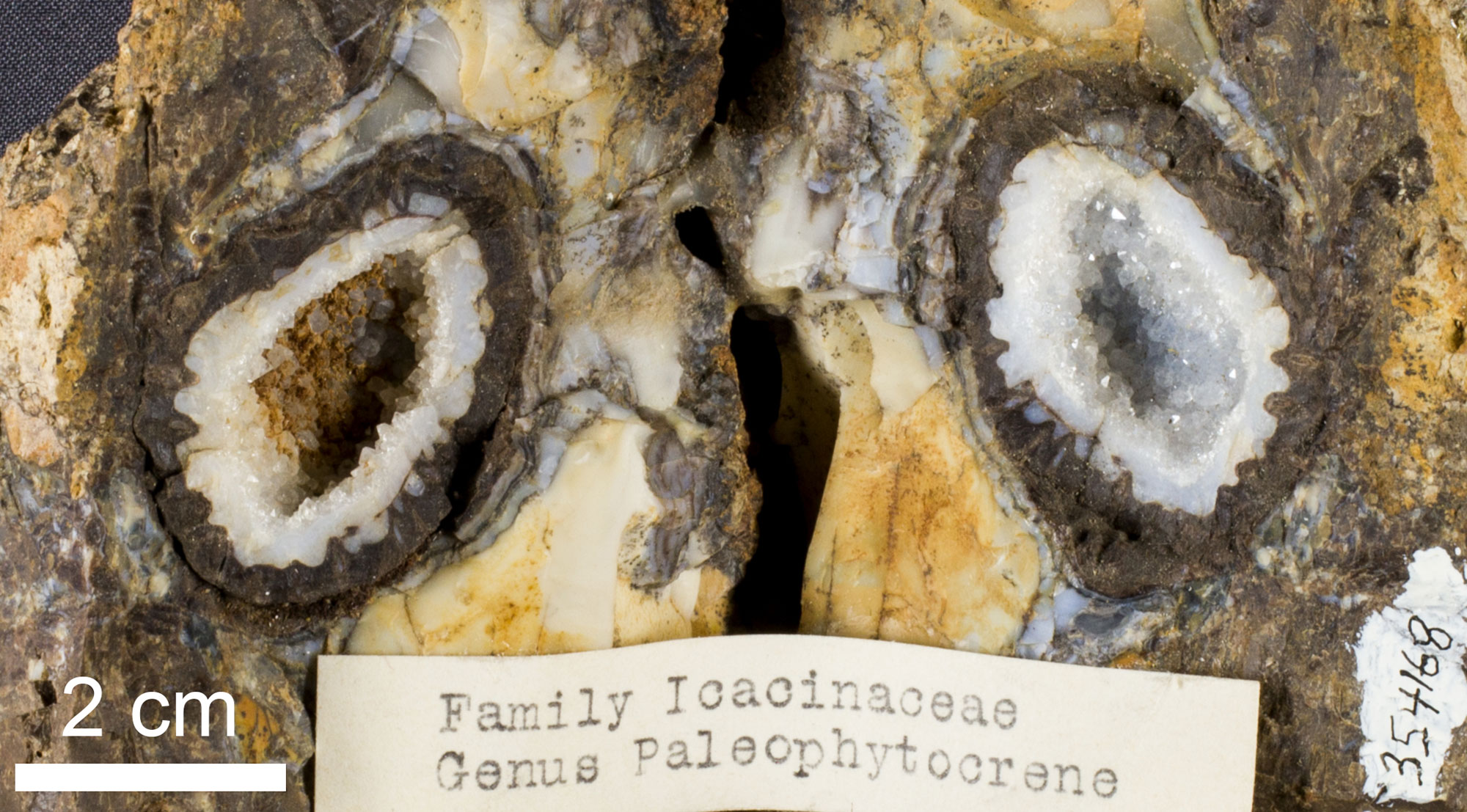

The Eocene Clarno Formation, exposed at several sites in central Oregon, consists of a series of volcanic ash deposits, which quickly buried plants and animals and protected them from decomposition. The resulting spectacular fossils include hundreds of kinds of leaves and seeds, as well as insects, mammals, and other animals. The famous Clarno “nut beds” exposed in Wheeler County in north-central Oregon have yielded more than 170 species of fossil fruits and seeds. Clarno fossil leaves include palms, bananas, and many flowering tree species. These fossils indicate that between 50 and 44 million years ago, the climate of what is now the Pacific Northwest was warm and humid.

Pit (hard, inner wall) from a fruit of Paleophytocrene, an extinct plant in the tropical family Icacinaceae, from the Eocene Clarno Formation, Oregon. The fruit pit has been broken in half and looks like a brown ring lined with white crystals. Photo of USNM PAL 354168 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Fossil walnuts (Juglans clarnensis) from the Eocene Clarno Formation, Wheeler County, Oregon. Photo of YPM PB 035771 by Linda S. Klise (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Skull of Zaisanamynodon protheroi, an extinct relative of rhinoceroses, from the Eocene Clarno Formation, Oregon. Fossil on display at the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Photo by Steve Lew (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-SharkeAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Oligocene John Day Formation

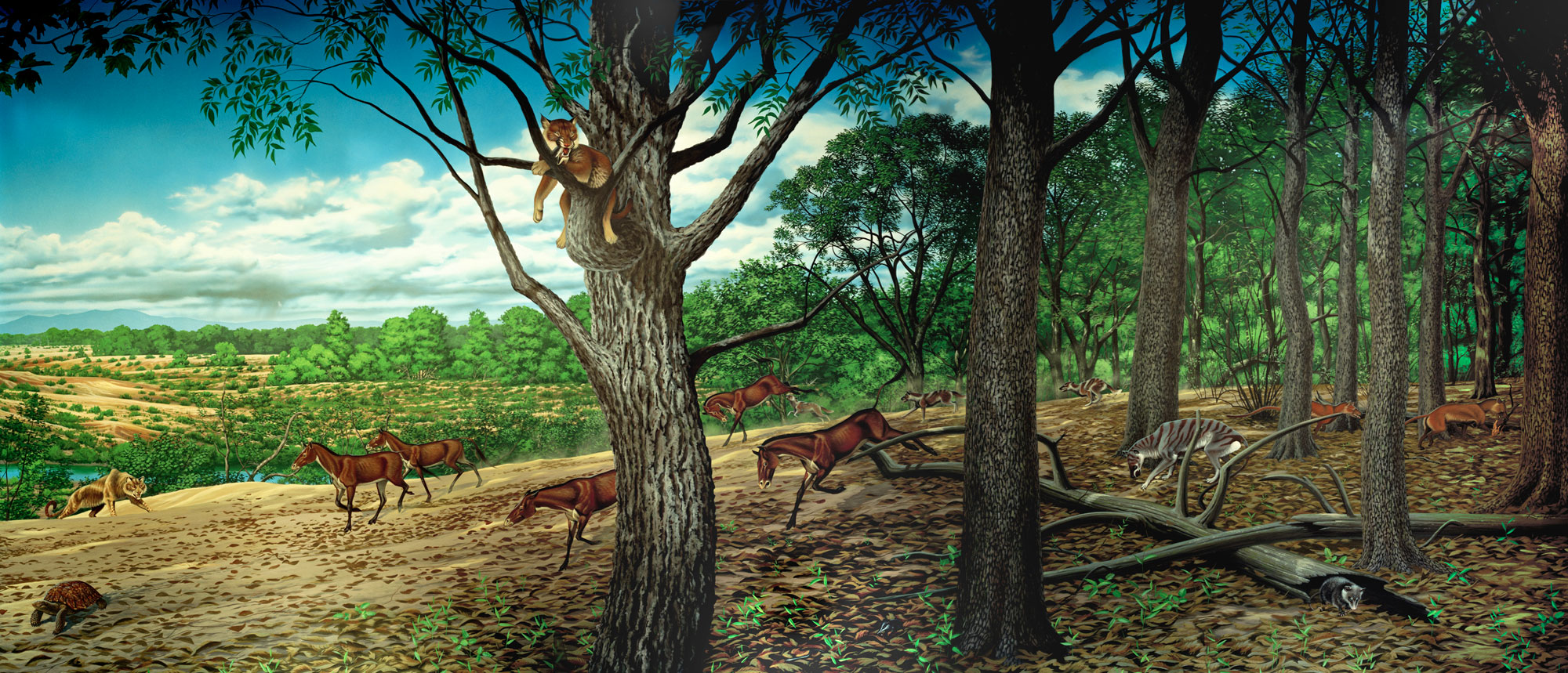

The Oligocene John Day Formation is another series of volcanic ash layers rich in fossil plants and animals, which formed between 35 and 25 million years ago. The climate was cooler, but species diversity was still high.

Fossils found in the John Day Formation include more than 60 species of plants, including the “dawn redwood” (Metasequoia), a relative of the living giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron gigantea) and coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Although dawn redwoods where once widespread in the northern hemisphere, China is the only country where they grow in the wild today. Dawn redwood differs from both giant sequoias and the coast redwood in that it is deciduous (meaning that it loses its leaves seasonally rather than remaining evergreen like most conifers). Examples of other plants from the John Day Formation include alder (Alnus), hornbeam (Paracarpinus), katsura (Cercidiphyllum), maple (Acer), and oak (Quercus).

The John Day Formation also contains more than 100 species of mammals, including entelodonts ("hell pigs"), oreodonts, other artiodactyls (even-toed hoofed mammals), nimravids (false saber-toothed cats), horses, rhinoceroses, camels, and rodents.

Mural depicting the plants and animals of the Oligocene Turtle Cove Member of the John Day Formation by Roger Witter. Photo by John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Alder (Alnus) leaves and "cones" (groups of female flowers or fruits, but not true cones) from the Oligocene John Day Formation, Oregon. Fossils on display at the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Left photo and right photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Skull of the artiodactyl (even-toed hoofed mammal) Promerycochoerus from the Oligocene John Day Formation of Oregon. Photo by Bruce Martin (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Skull of the canid Mesocyon from the Oligocene John Day Formation of Oregon. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Skulls of nimravids, or false saber-toothed cats, from the Oligocene John Day Formation, Oregon. These animals appear cat-like, but are not true cats and are not related to true saber-toothed cats. Left: Dirk-toothed nimravid (Dinictis cyclops). Right: John Day "tiger" (Pogonodon platycopis). Photos by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Skull of a fossil beaver (Paleocastor peninsulatus) from the Oligocene John Day Formation of Oregon. Photo of USNM V 7722 by Bruce Martin (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

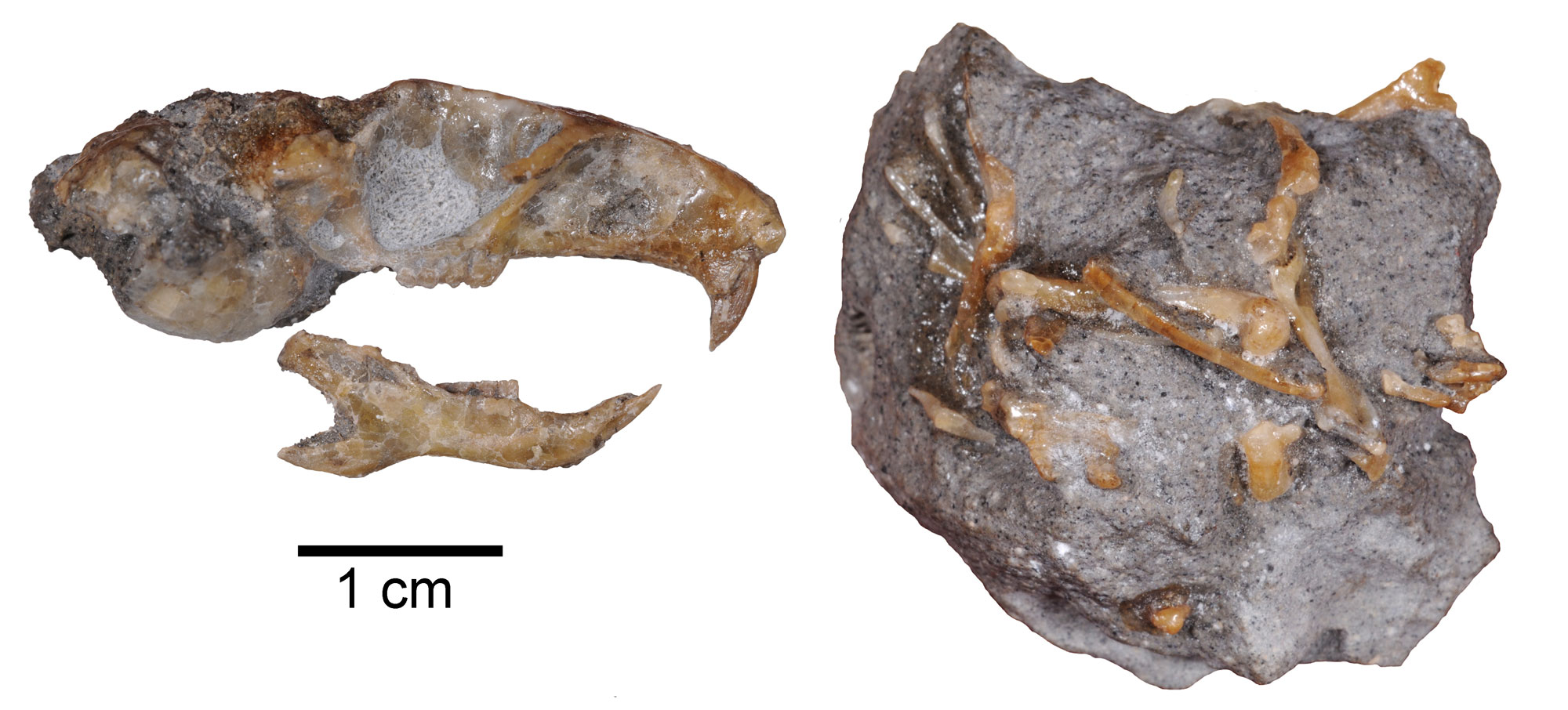

Skull (left) and bones (right) of a birch mouse (Proheteromys latidens) from the Oligocene of the John Day Basin, Oregon. This specimen was found on BLM land near John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Photo by John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Miocene Mascall Formation

Following the eruption of the Columbia River Basalt flows, between 17 and 12 million years ago, further ashfalls from eruptions in the Cascades formed the early to middle Miocene Mascall Formation. The Mascall Formation preserves another diverse assemblage of mammals, including horses, camels, rhinoceroses, bears, pronghorn, deer, weasels, raccoons, cats, and mastodonts. Plant fossils include ginkgo, dawn redwood, oak, sycamore, hackberry, maple, and elm, reflect the region’s cooling climate during this time period.

The flood basalts also contain one of the world’s most unusual fossils, the “Blue Lake Rhino,” in Grant County, Washington. It is an external mold of a rhinoceros, which lived around 14.5 million years ago. It apparently formed when lava flowed into the water, forming pillows. These were still hot enough to be soft but not hot enough to completely burn away the body.

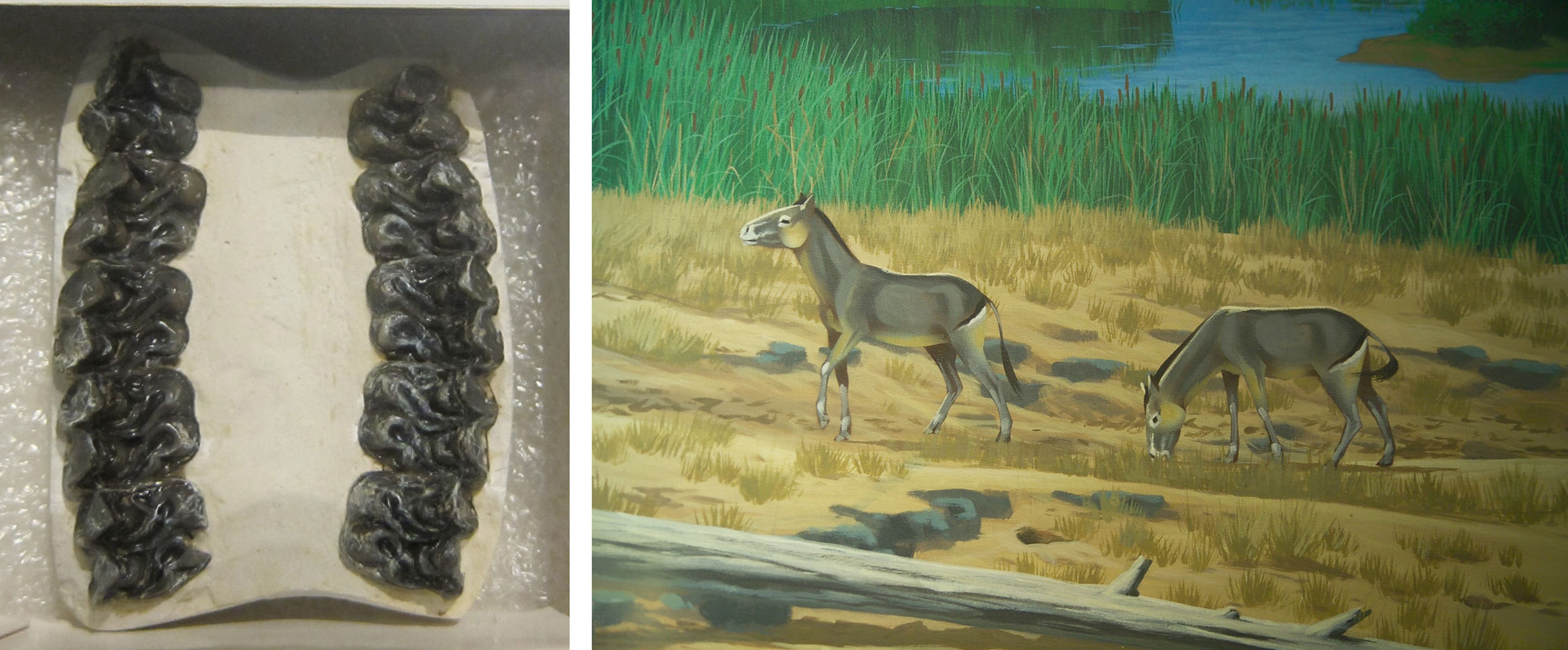

An early horse (Archaeohippus) from the Miocene Mascall Formation, Oregon. Left: Fossil teeth. Right: Artist's reconstruction of Archaeohippus from a mural at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Left photo and right photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

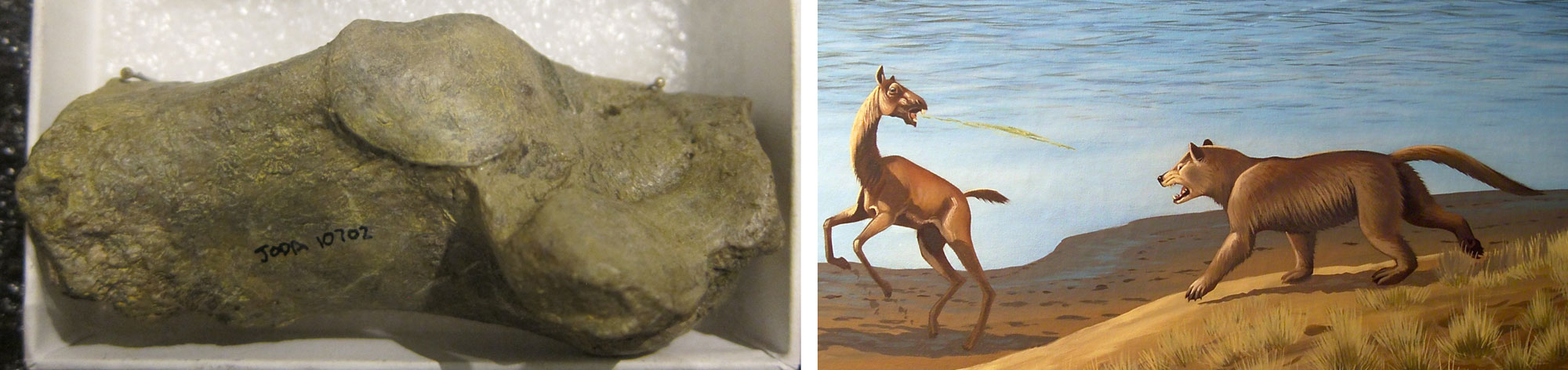

Mammals from the Miocene Mascall Formation, Oregon. Left: Heel bone of a bear-dog (Amphicyon). Right: Artist's reconstruction of a bear-dog (Amphicyon) chasing a camel (Miolabis) from a mural at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Left photo and right photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Lower jaw of an gomphothere (Gomphotherium cingulatum), Miocene Mascall Formation, Oregon. Gomphotheres are elephant-like animals. Specimen on display at the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Photo by daveynin (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Molars of an early mastodont (Zygolophodon), Miocene Mascall Formation, Oregon. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Hackberry (Celtis) seeds, Miocene Mascall Formation, Oregon. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Miocene Rattlesnake Formation

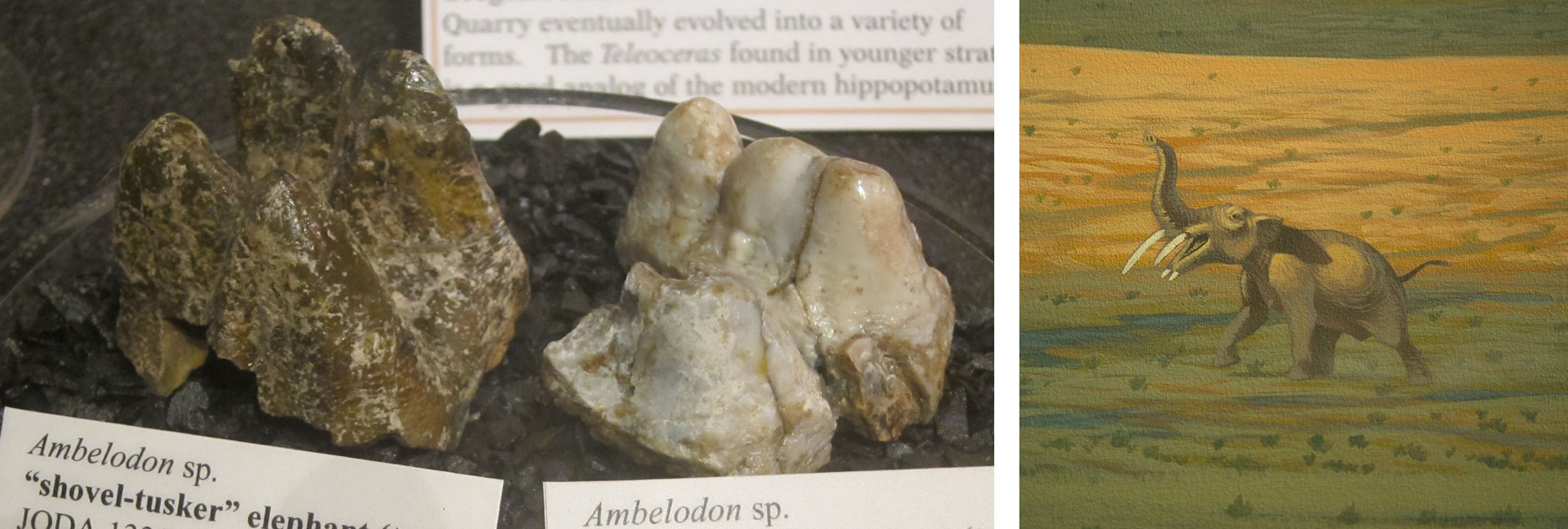

The youngest fossil-bearing unit at John Day Fossil Beds is the Rattlesnake Formation, which dates to the late Miocene, about 7 million years ago. As with the older rock units, it preserves a diverse mammal fauna. These include animals like rodents, camels, horses, peccaries, rhinoceroses, shovel-tuskers (elephant-like animals), foxes, and short-faced bears. The world's oldest fisher (Pekania occulta), a type of mustelid (a group including weasels and skunks), has been recorded from this formation.

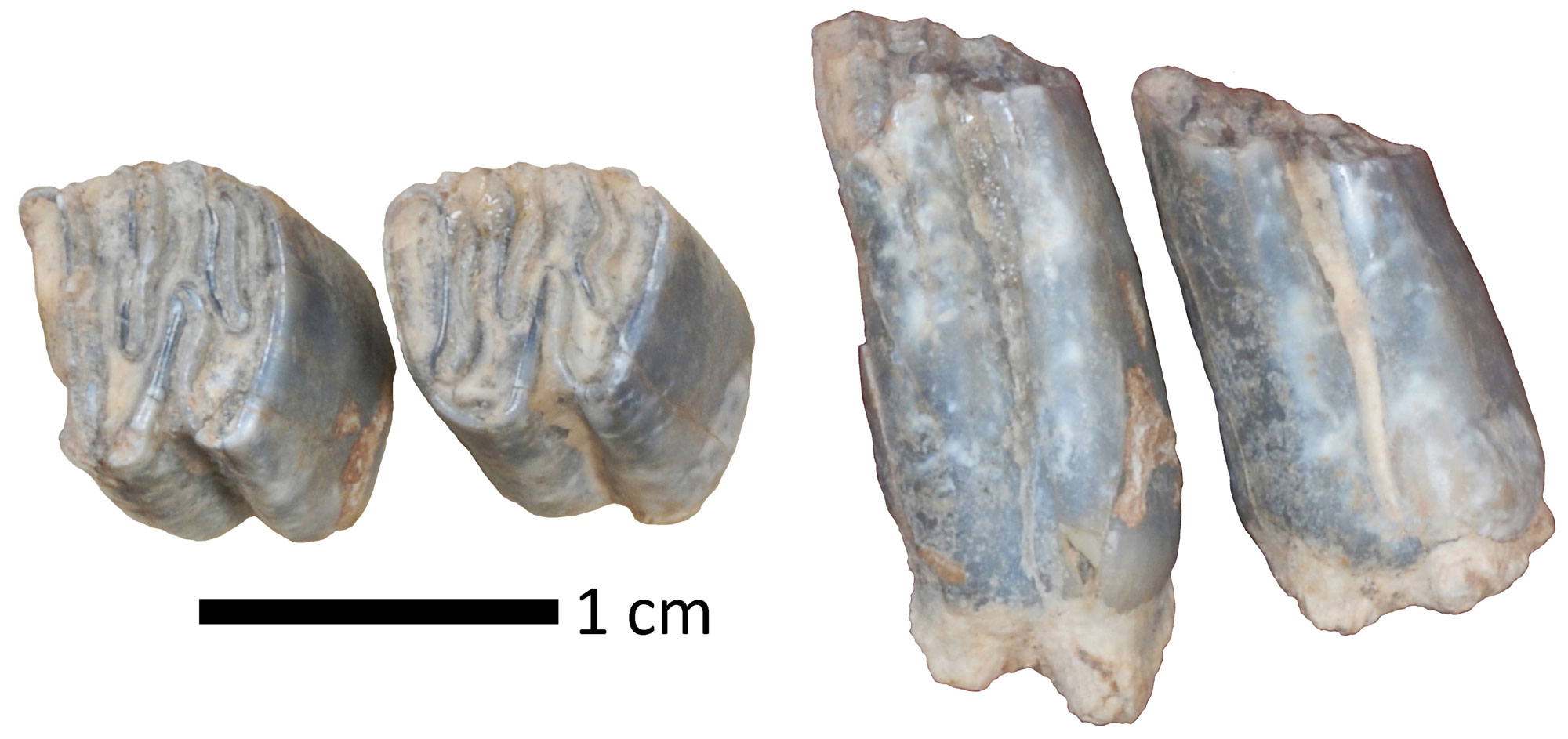

Beaver (Castor) teeth (left, top view; right, side view), Miocene Rattlesnake Formation, Oregon. Photo by Bureau of Land Management/BLM and National Park Service/NPS (BLM of Oregon and Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image reconfigured, cropped, and resized).

Shovel-tusker (Ambelodon) from the Miocene Rattlesnake Formation, Oregon. Left: Teeth. Right: Artist's reconstruction from a mural at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Left photo and right photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Short-faced bear (Indarctos oregonensis), Miocene Rattlesnake Formation, Oregon. Left: Teeth. Right: Artist's reconstruction from a mural at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Left photo and right photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Quaternary fossils

Large mammals, including woolly mammoths and camels dating from the Quaternary, have been found in a variety of locations representing ancient riverbanks and lakes. The oldest known mastodon (another relative of modern elephants) in North America comes from the Ringold Formation at White Bluffs in south-central Washington.

Mammoth tracks (circular impressions) at Fossil Lake, Oregon, 2017. Photo by Greg Shine (Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Tooth shards from an extinct Plesitocene camel (Camelops). These specimens come from the Rimrock Draw Shelter, an important archeological site near Riley, Oregon. A stone tool and spearpoints have also been found at the site. University of Oregon Archaeological Field School (Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central United States: Fossils of the Columbia Plateau (continues coverage of the Columbia Plateau in Idaho): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-cp/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/