Topics covered on this page: Mesozoic fossils; Mesozoic marine fossils; Dinosaurs; Cenozoic marine invertebrate fossils; Paleogene marine invertebrate fossils; Neogene marine invertebrate fossils; Quaternary marine invertebrate fossils; Cenozoic marine vertebrate fossils; Cenozoic sharks and rays; Cenozoic marine mammals; Cenozoic aquatic and terrestrial fossils; Eocene Chuckanut Formation; Desmostylians; Quaternary terrestrial fossils; The La Brea Tarpits; The Pacific mastodon; The Channel Islands pygmy mammoth; Resources.

Credits: Some of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Western US" by Brendan M. Anderson, Alexandra Moore, Gary Lewis, and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions and additions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated May 3, 2022.

Image above: Recreation of a Columbian mammoth trapped in a tarpit, La Brea Tarpits, Los Angeles, California, 2012. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith (Reproduction number LC-DIG-highsm-21992, Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, no known restrictions on publication).

Mesozoic fossils

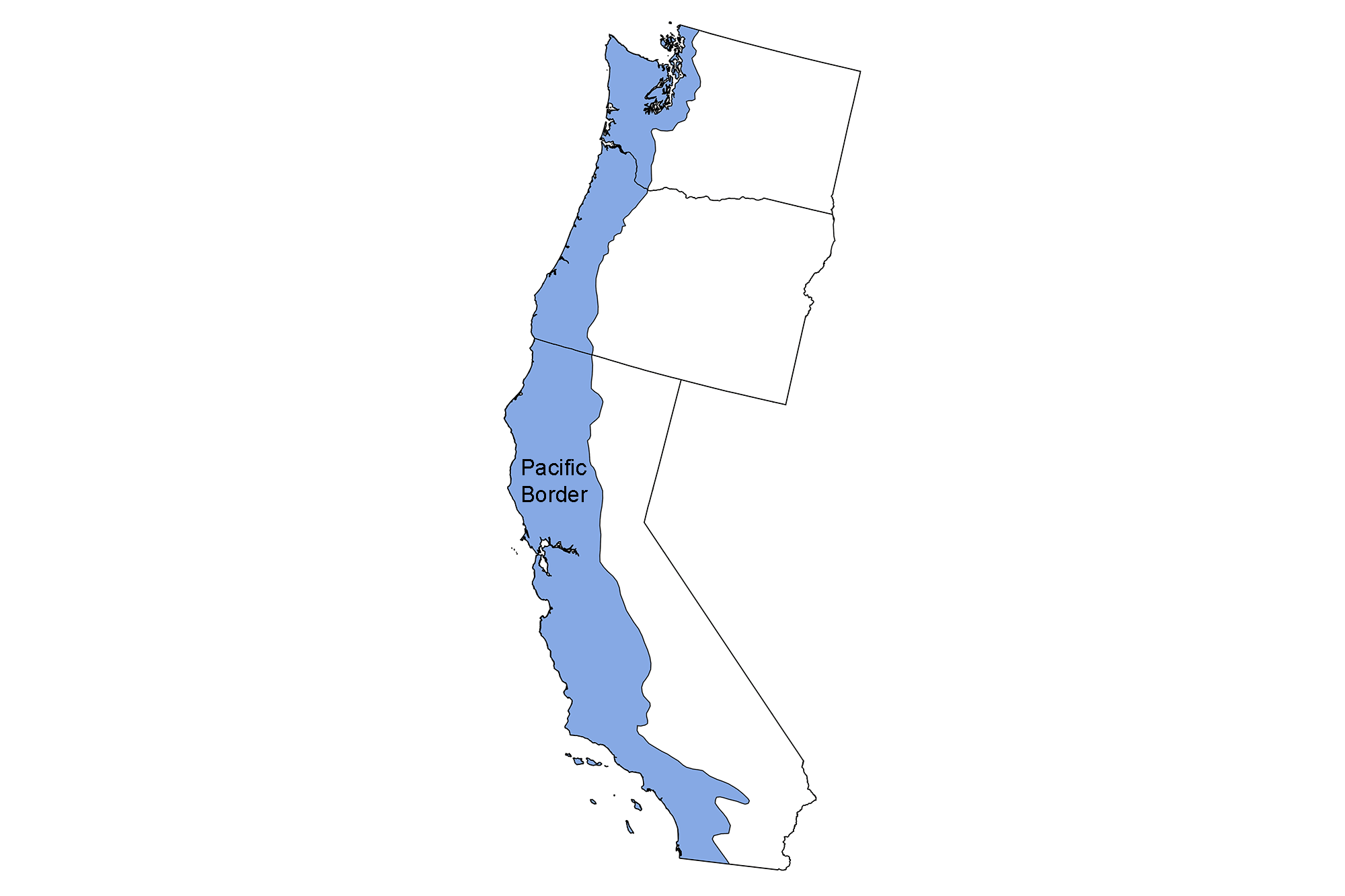

The Pacific Border includes terranes and former island arcs that accreted onto the West Coast, along with sediments deposited after this merger. Nearly every newly-exposed hillside or roadcut in this region exposes fossiliferous sediment, even in developed areas. Fossil-bearing rocks of Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous age can be found in this region in north-central California to southwestern California and in southwestern Oregon.

Mesozoic marine fossils

Triassic to Jurassic

In north-central California, Triassic rocks yield ammonoids and marine reptiles, including the icthyosaur Shastasaurus and the thalattosaur Thalattosaurus. Jurassic marine fossils include abundant clams such as Buchia and ammonoids.

Two views of the Triassic ammonoid Tropites sububullatus pacifica from Brock Mountain, California. Photos of UC 32543 by Alex P. Layng, Field Museum of Natural History (copyright Field Museum of Natural History, Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial license, accessed via GBIF.org, images cropped and resized).

Thalattosaurus alexandrae, an extinct reptile named Annie Alexander, an heiress who financed the creation of the University of California Museum of Paleontology. Left. Drawings of the skull. Source: Merriam (1905) Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, vol. 5 (Wikimedia Commons). Right: Reconstruction of the living animal by Nobu Tamura (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

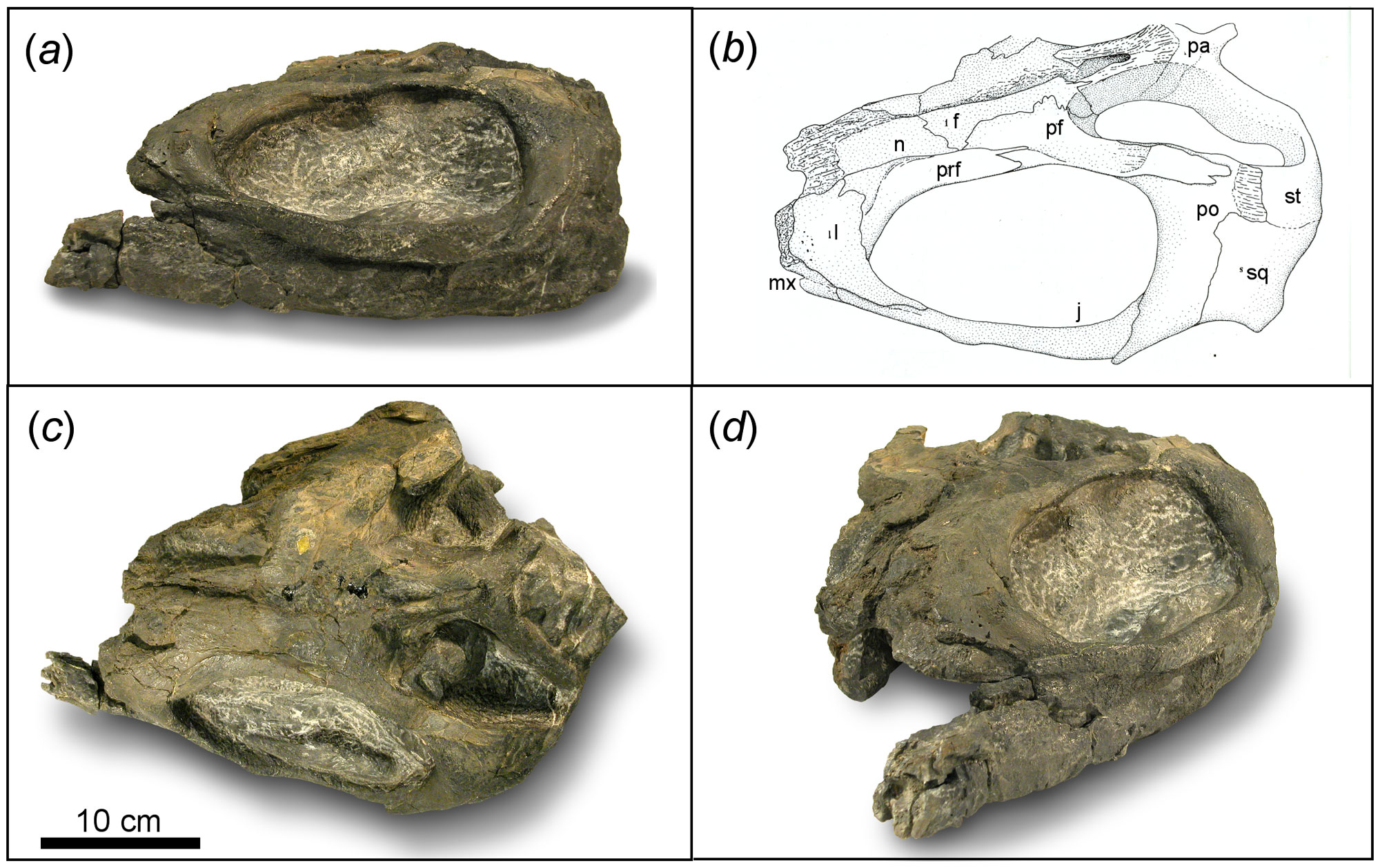

Different views of the skull of Shastasaurus pacificus, an ichthyosaur from the Triassic of California. Scientists think that Shastasaurus may have had a short snout and no teeth. A, B. Lateral views. C. View from above. D. Oblique view showing the front of the skull. Source: Figure 5 from Sander et al. (2011) PLoS ONE e19480 (Creative Commons Attribution license, image resized).

Cretaceous

During the Cretaceous, sea levels were higher, and the Pacific shoreline was much further inland. The shore was lined with palms, and the waters were filled with bivalves such as Inoceramus and Trigonia. Recognizable relatives of many extant bivalves, such as oysters, also became common during the Cretaceous. Ammonoid cephalopods were extremely diverse and can be found in many Cretaceous rocks. Marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs are also found through much of coastal California.

In addition to marine fossils, Cretaceous plants have been found on Sucia Island off the coast of Washington state, including fruits of plants in the dogwood family (Cornaceae) as well as winged fruits of a member of Cunoniaceae, a family of plants found in the southern hemisphere today.

A heteromorph ammonoid (Helicancylus pilsbryi) from the Early Cretaceous Budden Canyon Formation, Shasta County, California. Photo of LACMIP 9951.3 by Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

An ammonoid (Acanthoplites subbigoti) from the Early Cretaceous Budden Canyon Formation, Shasta County, California. Photo of LACMIP 9951.2 by Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

An acanthoceratoid cephalopod (Romaniceras deverioide), Late Cretaceous Redding Formation, Shasta County, California. Photo of LACMIP 10741.4 by Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

The giant bivalve Inoceramus from the Cretaceous of Little Sucia Island, San Juan Islands, Washington. Photo by Kevmin (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped).

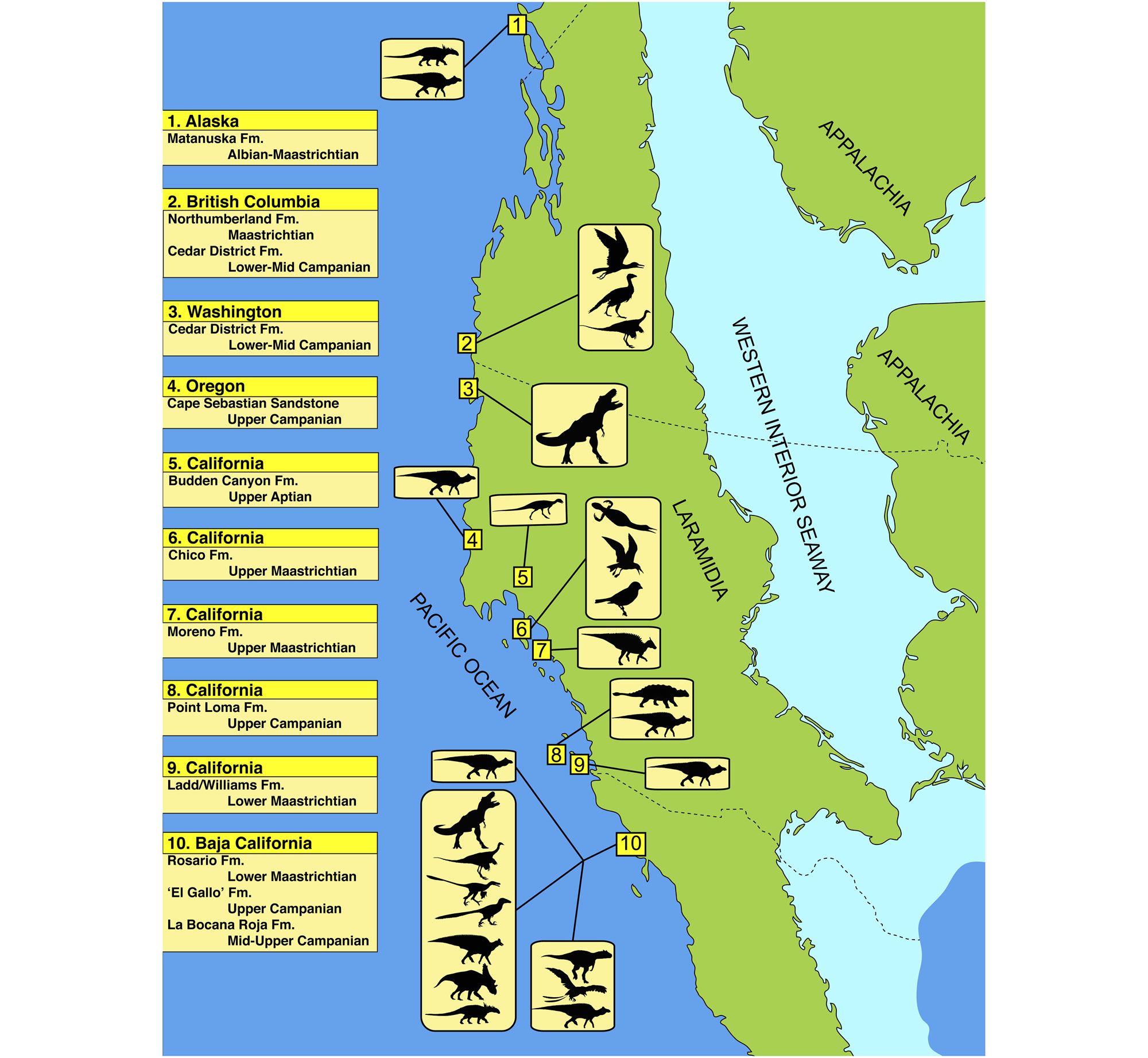

Dinosaurs

Although there were presumably many dinosaur species on land, only a few dinosaur fossils have been found in this region. These include the bones of hadrosaurs and the Late Cretaceous armor-plated ankylosaur Aletopelta. One specimen of Aletopelta found in California evidently floated out to sea, where its armor plates and spines were encrusted by bivalves!

Specimen of Aletopelta with encrusted bivalves on display in San Diego, California. Photo by ケラトプスユウタ(Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Life reconstruction of Aletopelta by Karkemish (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Distribution of dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Pacific Coast known as of 2015. Source: Figure 1 from B. R. Peecock and C.A. Sidor (2015) PLoS ONE 10(5): e0127792 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Cenozic marine invertebrate fossils

Paleogene marine invertebrate fossils

The Paleogene marine fossils of the Pacific Border strongly resemble the hard-shelled organisms living in the Pacific today, although some may seem geographically out of place, which is an important piece of evidence for environmental change through geological time. Gastropods and bivalves are the most common marine fossils of the Paleogene and include clams, oysters, whelks (family Buccinidae), moon snails (family Naticidae), and tower snails (family Turritellidae).

Single valve of a clam shell (Pitaria californiana) shell from the Eocene Cowlitz Formation, Cowlitz County, Washington. Photo of PRI 76124 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Two views of a snail shell (Amaurellina clarki clarki) shell from the Eocene Cowlitz Formation, Lewis County, Washington. Photo of PRI 76176 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

A nautiloid (Aturia angustata) from the Oligocene Lincoln Creek Formation, Grays Harbor County, Washington. Photo by Kevmin (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped).

A crinoid (Isocrinus oregonensis) from the Oligocene Keasey Formation, Columbia County, Oregon. Photo of USNM MO 560790 by the Crinoid Type Image Project (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Crabs are sometimes common, although it is rare to find fossils of whole animals, as these organisms typically break apart after death. However, some locations preserve crabs (and other fossils) within concretions. Concretions are hard, layered nodules, often with a different chemical makeup from the surrounding rock. They form when minerals precipitate (crystalize) around a nucleus within the sediment. While concretions are not fossils themselves, they may contain fossils. Even trace fossils may be preserved in concretions, as many organisms line their burrows with mucus, and the decay of that mucus may begin the formation of a concretion.

A crab (Branchioplax washingtoniana) from the Oligocene Callam Formation, Kitsap County, Washington. Photo of YPM IP 000195 by Jessica Utrup, 2017 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

A crab (Pulalius vulgaris) from the Oligocene Lincoln Creek Formation, Wahkiakum County, Washington. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Neogene marine invertebrate fossils

The general character of fossils from the Neogene is similar to that of the Paleogene; Neogene fossils can be found near the coast as well as in the Central Valley area of California. Marine invertebrates include bryozoans, corals, mollusks, and echinoderms. Gastropods such as moon snails, whelks, and tower snails are important in the marine fauna. Mussels, clams, scallops, and oysters are all common and can often be found in the rocks exposed at beach cliffs along much of the Oregon and California coasts.

A scleractinian coral (Astrangia coalingensis) shell from the Pliocene San Joaquin Formation, Kings County, California. Photo of PRI 71881 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

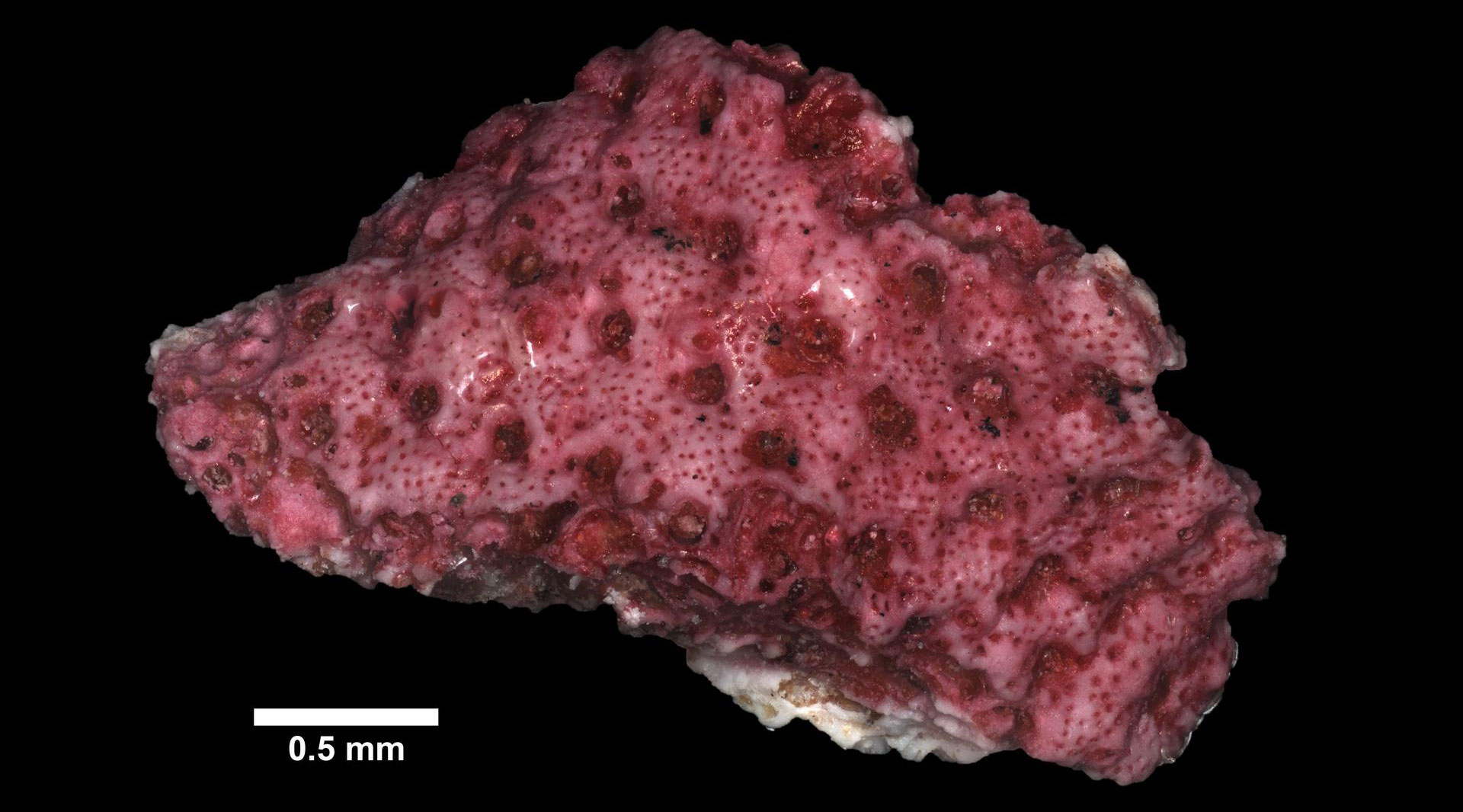

A bryozoan (Schizoporella cornuta) from the Miocene of Santa Barbara Island, a small island off the coast of Southern California. Photo of YPM IP 591115 by Daniel J. Drew, 2017 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Two views of a Calliostoma top snail (Calliostoma coalingense) from the Pliocene Etchegoin Formation, California. Photo of PRI 71586 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Two views of a moon snail (Polinices galianor), Pliocene, San Diego County, California. Left photo and right photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication).

Clam (Pitar dalli) shells from the Miocene of Pacific County, Washington. Photo of PRI 76135 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Scallops (Patinopecten coosensis) from the Miocene Empire Formation, Coos County, Oregon. Photo of PRI 76312 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

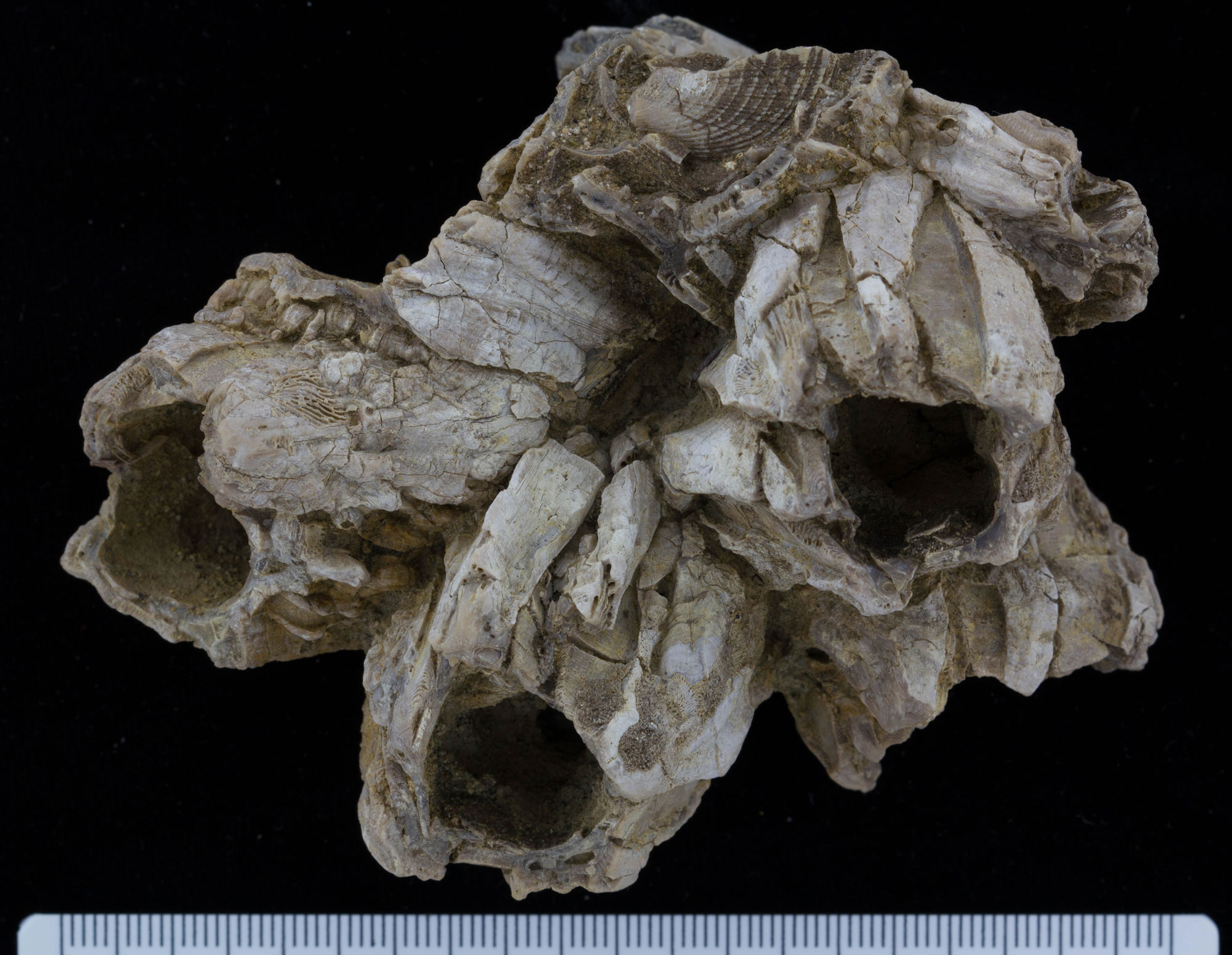

Oysters (Crassostrea titan) from the Miocene Santa Margarita Formation, Fresno County, California. Photo of PRI 72940 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Sand dollars (Dendraster excentricus) from the Pliocene of La Jolla, California. Photo of YPM IP 227814 by Susan H. Butts, 2021 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Barnacles (Tamiosoma gregaria) from the Pliocene San Joaquin Formation, California. Photo of PRI 71257 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Quaternary marine invertebrate fossils

Prior to 100,000 years ago, much more of the coast was submerged, and the region was ultimately exposed when the expansion of glaciers caused a regression in sea level. The coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington and the central valley of California contain numerous Pleistocene-age fossil deposits. Bivalves and gastropods are the most common marine invertebrate fossils from this time, particularly scallops (Pecten) and oysters (Ostrea), but also clams such as Saxidomus, Mya, and Clinocardium and snails such as Polinices, Neptunea, Turricula, and Cancellaria.

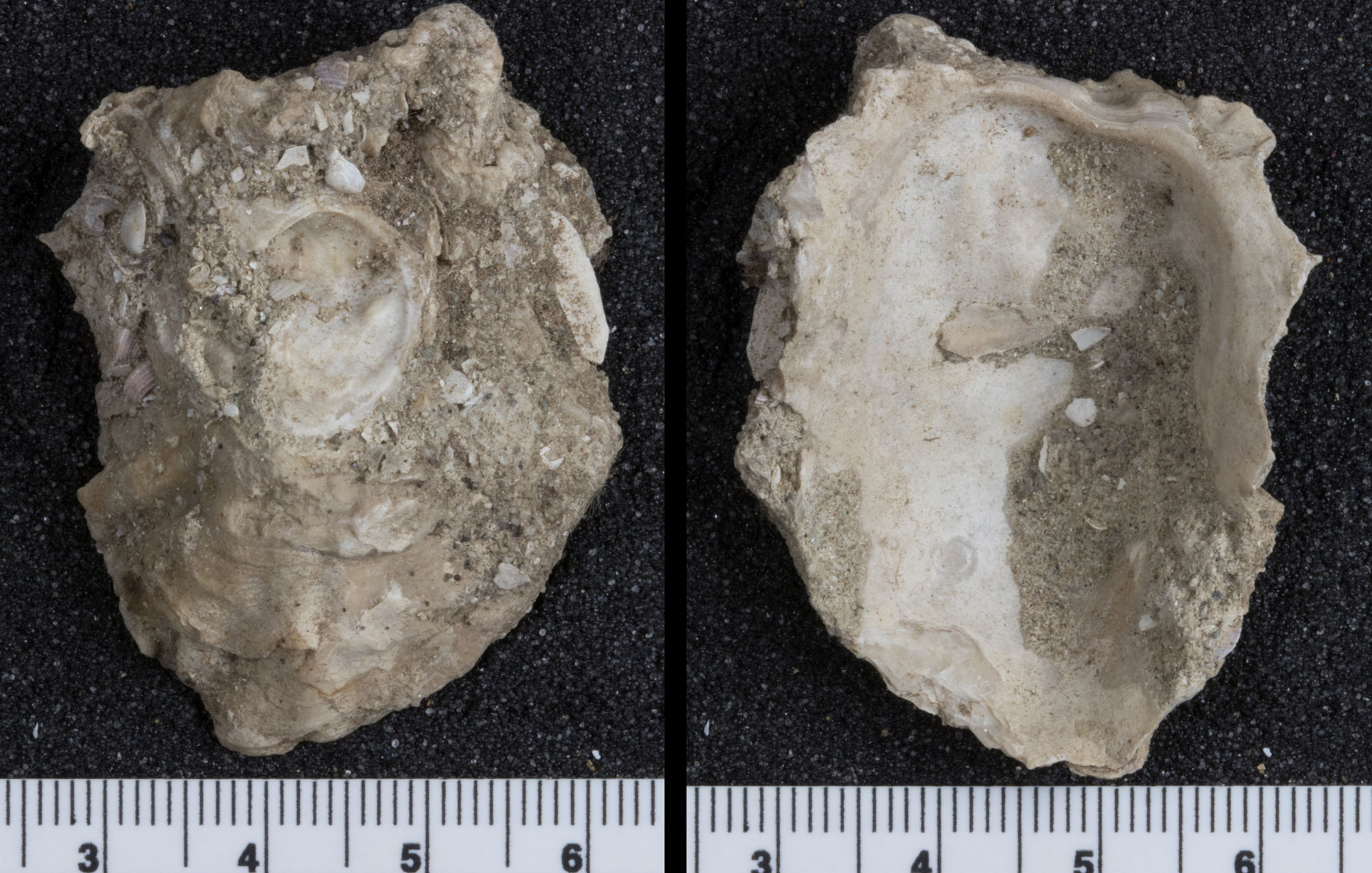

Outer and inner surface of a single valve of an oyster shell (Ostrea lurida) from the Pleistocene Palos Verde Sand, Los Angeles, California. Photo of PRI 75917 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Outer and inner surface of a single valve of a clam shell (Simomactra planulata) from the Pleistocene Palos Verde Sand, Los Angeles, California. Photo of PRI 75950 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Worm snails (family Vermetidae) from the Pleistocene of Humbolt County, California. Photo of PRI 76553 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Horn snails (Cerithideopsis californica) from the Pleistocene of San Diego County, California. Photo of PRI 76599 by the Paleontological Research Institution/PRI (CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Cenozic marine vertebrate fossils

Marine vertebrates include sharks, rays, bony fish, and marine mammals such as seals, walruses, sea cows, toothed whales (including dolphins), and baleen whales. Birds, including auks (Mancalla vegrandis), are also known.

Cenozoic sharks and rays

Sharks and rays have skeletons made of cartilage instead of bone, which means that their skeletons are rarely found as fossils. The teeth of sharks and rays, however, are much more resistant. They are common fossils in Cenozoic sediments on the Pacific Border.

Sharks shed their teeth constantly, and a single individual can produce as many as 35,000 teeth during its lifetime. You can tell the difference between fossil and modern shark teeth by their color. Fossil teeth are often brown, gray, or black, whereas modern teeth are tan to white. Shark teeth come in many forms and sizes, and not all teeth in the mouth of a single individual look alike.

The largest shark that ever lived was a species related to the modern great white shark, but much bigger. Otodus megalodon—frequently called just "megalodon"—lived in the eastern Pacific Ocean from the Miocene to the Pliocene. The fossil record of megalodon consists almost entirely of teeth. While megalodon is regarded as one of the largest and most powerful ocean predators that ever lived, size estimates for this shark vary widely because of the lack of body fossils. Nevertheless, a reasonable estimate is that megalodon reached lengths of up to 18 meters (59 feet). It likely fed on large whales.

Two views of a megalodon (Otodus megalodon) tooth, Pliocene San Mateo Formation, San Diego County, California. Source: Figure 7 from Boessenecker et al. (2019) PeerJ 7: e6088 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Cenozoic marine mammals

Cenozoic whales

Whales are most closely related to artiodactyls, or the even-toed hoofed mammals (for example, bison, deer, and hippopotamuses). Whales evolved from four-legged mammals that lived on land during the Eocene epoch, beginning around 55 million years ago. The early ancestors of whales were animals that resembled wolves. Fossils—especially from Egypt and Pakistan—have revealed many extinct forms that show the evolutionary steps in the remarkable transition from land-dwelling to truly aquatic animals. Some transitional Eocene whales are known from the southeastern and south-central United States.

There are two major groups of modern whales. The toothed whales or odontocetes (meaning "toothed whales") include dolphins, porpoises, and the sperm whale. The toothless baleen whales or mysticetes include the large, plankton-feeding whales such as humpback whales, blue whales, and right whales.

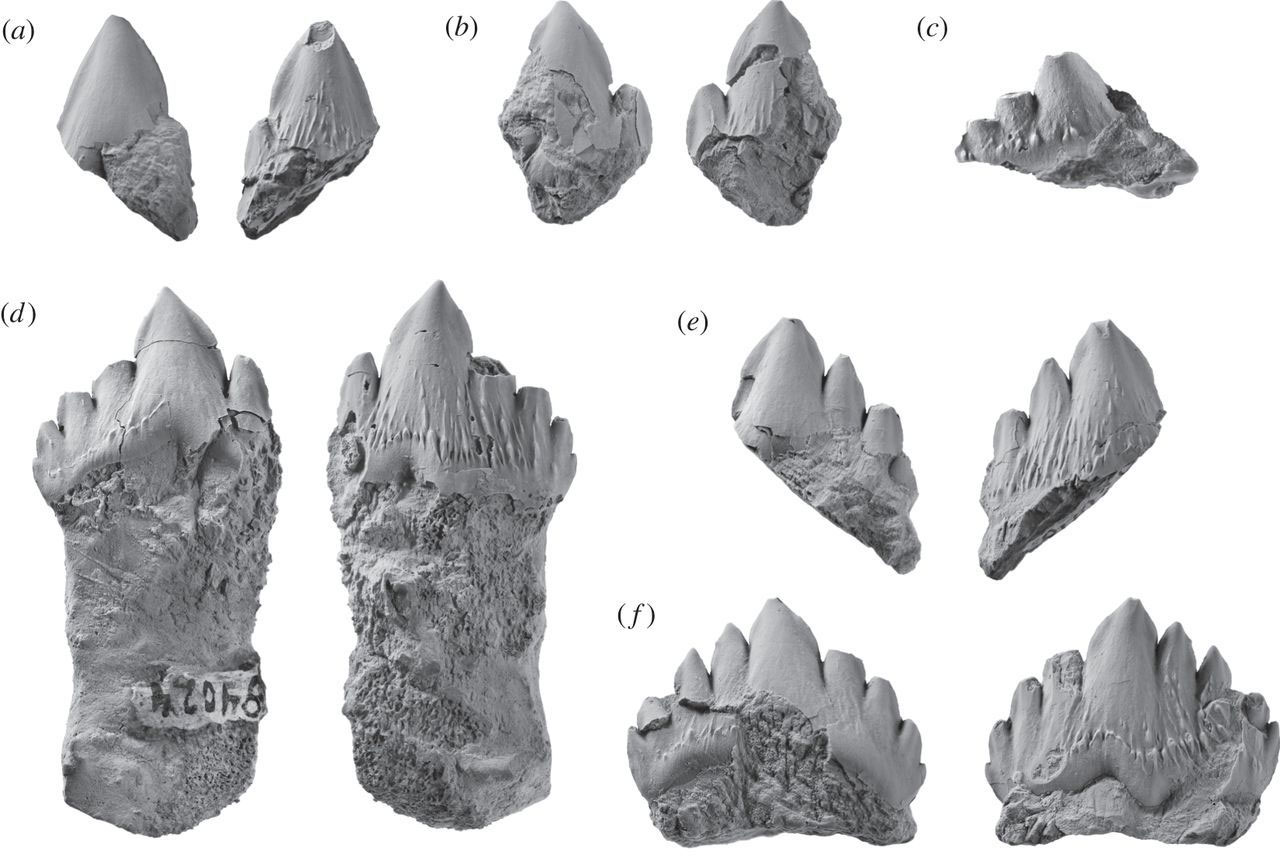

Fossils of whales and dolphins can be found in Oligocene and younger sediments along the West Coast of North America. Transitional aetiocetid, or toothed baleen whales, are found on the West Coast in the Oligocene. Although "toothed baleen" may appear to be a contradiction in terms, aetiocetids are toothed ancestors of the modern baleen whales.

Teethed of an aetiocetid or toothed baleen whale (Fucaia buelli) from the early Oligocene Makah Formation, northwestern Washington. Source: Figure 10 from Marx et al. (2015) Royal Society Open Science 2: 150476 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

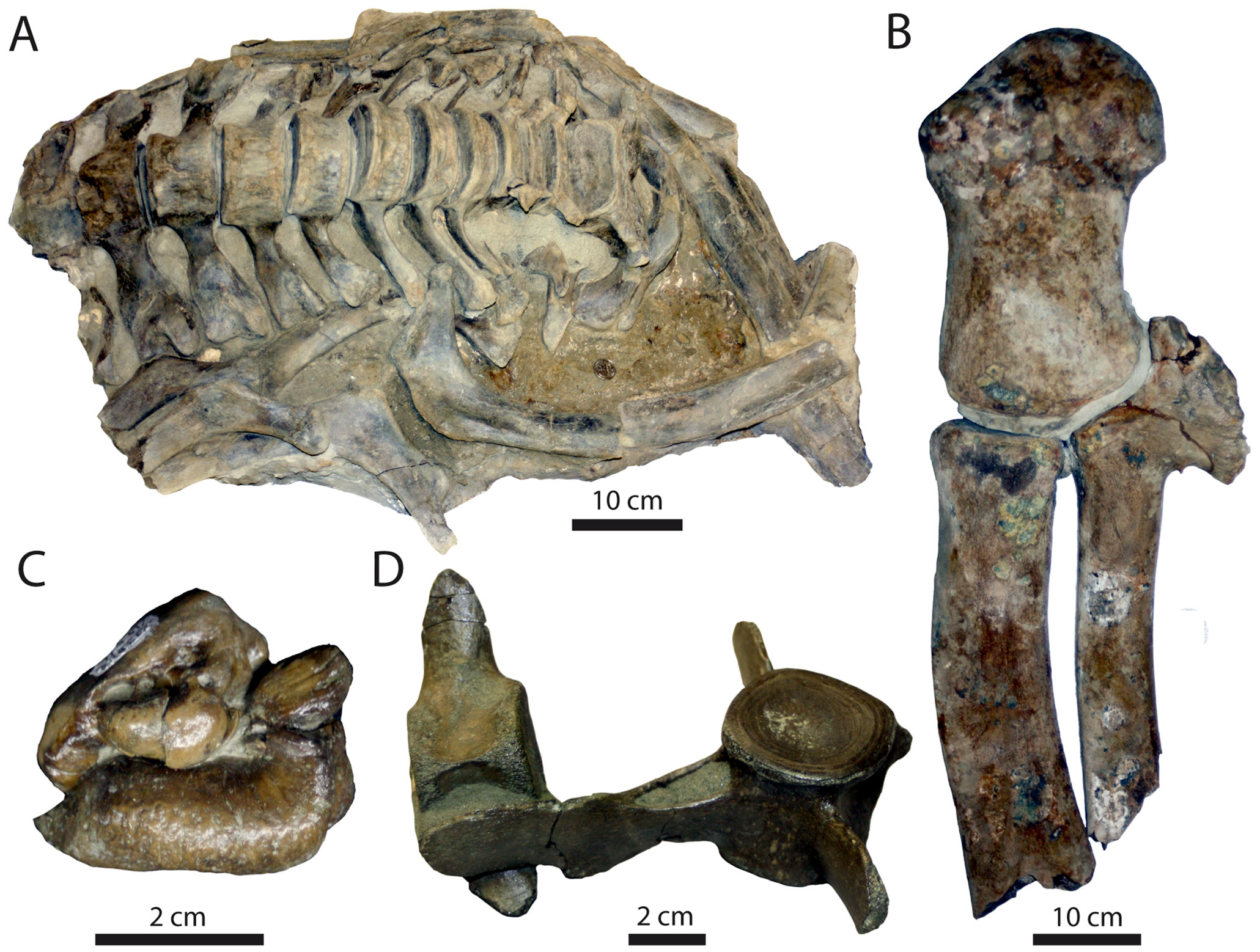

Whale bones from the Miocene to Pliocene Purisima Formation, central California. A. Vertebrae and other bones of a baleen whale. B. Bones of the front flipper of a baleen whale. C. Ear bones of a toothed whale. D. Vertebrae of a toothed whale. Source: Figure 20 from Boessenecker et al. (2014) PLoS ONE 9(3): e91419 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Cenozoic sirenians

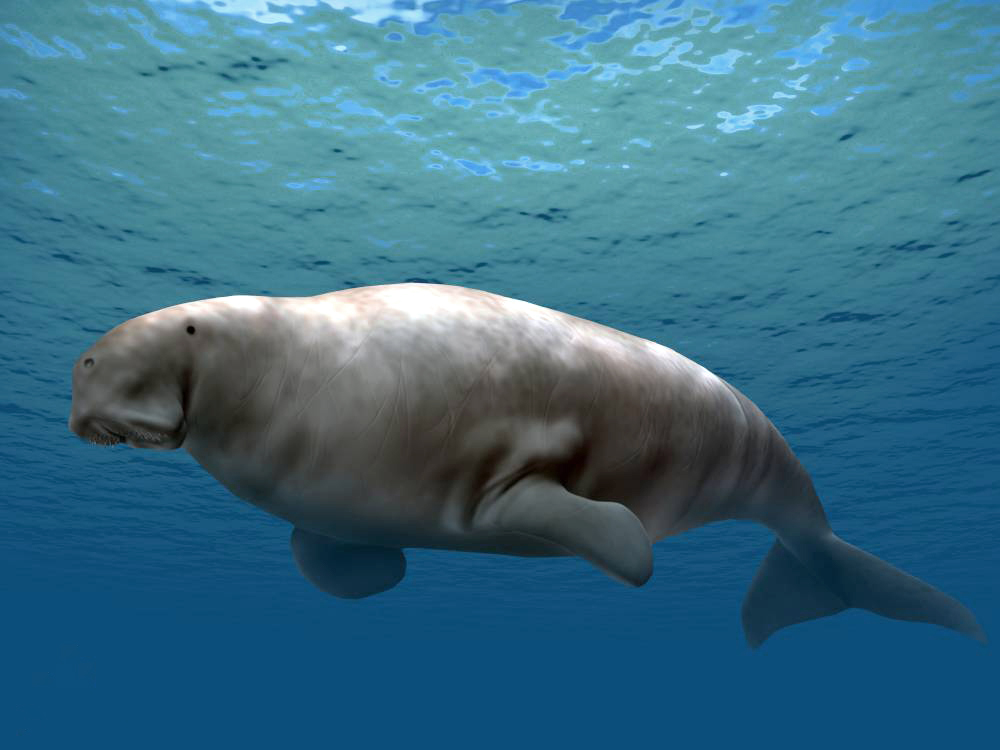

Manatees, dugongs, and sea cows belong to a group of aquatic mammals called sirenians. Sirenians are not closely related to whales. Among living animals, they are most closely related to elephants. Fossil dugongs or sea cows (both common names for members of the sirenian family Dugongidae) are found on the Pacific border. One of the oldest examples on the West Coast is from the Channel Islands off southern California and may date back as far as the late Oligocene.

Sirenians are no longer found in the eastern Pacific. The last West Coast sirenian, Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), had a Pleistocene range that extended from northern Alaska to Baja California in the east and from northeastern Russia to Japan in the west. By the time Europeans began exploring the North Atlantic, the range of the Steller's sea cow was restricted to a region around the Commander Islands east of the Kamchatka Peninsula (eastern Russia). The remaining small population was hunted to extinction sometime during the 1700s. During the Miocene and Pliocene, ancient relatives of the Steller's sea cow, Hydrodamalis cuestae and Dusisiren, lived in California.

Ribs of a sea cow, late Oligocene to Miocene, Santa Rosa Island, California. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

An artist's interpretation of Dusisiren jordani from the Miocene to Pliocene of California as it may have appeared in life. Illustration by Nobu Tamura (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

Ancient and historic ranges of Stellar's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas). Yellow shading = Pleistocene range; red dots = evidence from archaeological sites; blue dots = range at time of discovery by Europeans. Map from Figure 1 in Sharko et al. (2021) Nature Communcations 12: 2215 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image accessed via Wikimedia Commons).

Skeleton of the extinct Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas). Specimen collection location unknown (presumably the Commander Islands region), on display in the Musée des Confluences à Lyon. Photo by Vassil (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Cenozoic pinnipeds

Pinnipeds are a group of marine mammals with four flippers that are capable of coming out of the water and resting or moving around on land, at least for limited distances. Pinnipeds include three families: earless seals or true seals (Phocidae), eared seals (Otariidae, including fur seals and sea lions), and walruses (Odobenidae). Among living organisms, pinnipeds may be most closely related to bears; they are not closely related to whales or sirenians.

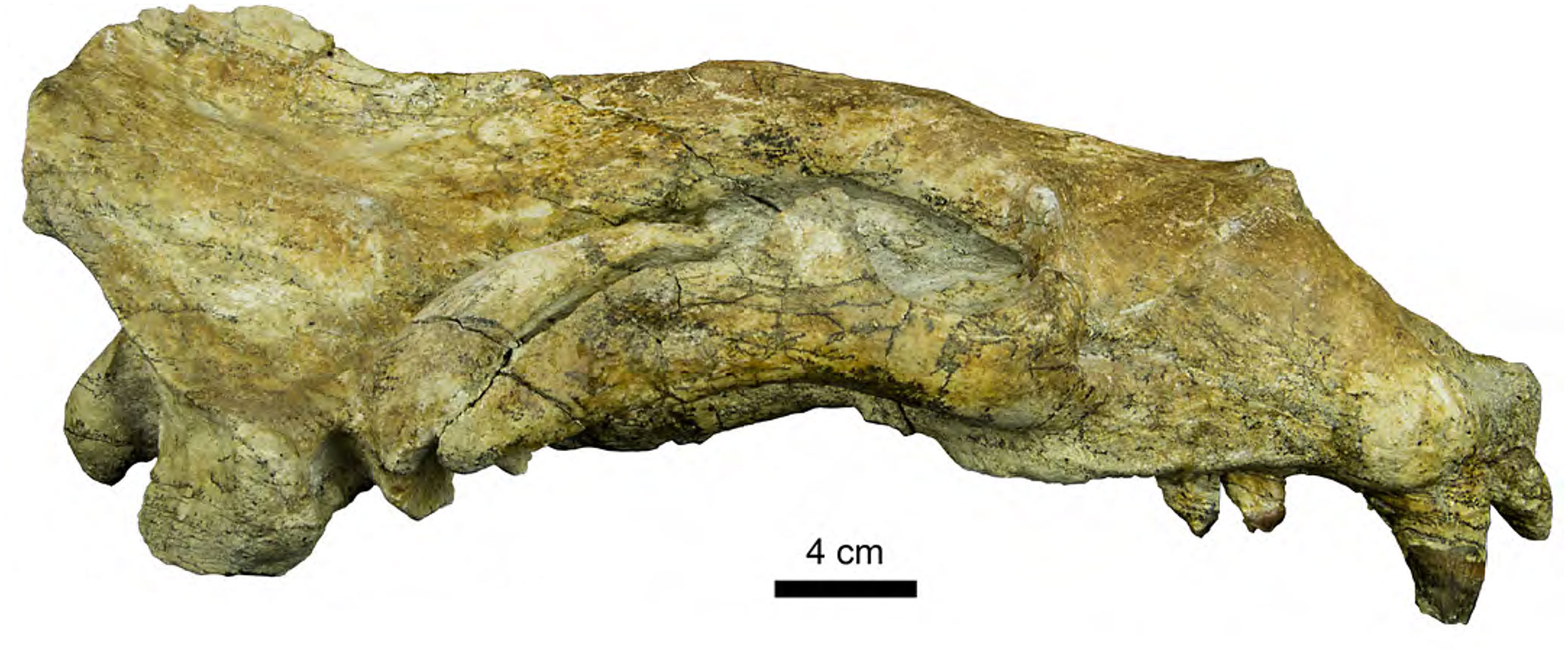

Some of the oldest known pinnipeds are from the West Coast. The oldest from this region is Enaliarctos, which comes from the late Oligocene to early Miocene of California and Oregon. Enaliarctos already looked recognizably seal-like. A similar early pinniped is also known from Washington.

While eared seals and walruses date to the Miocene on the West Coast, earless seals did not appear until the Pliocene. Today, earless and eared seals still occur on the California, Oregon, and Washington coasts. Only one species of walrus is living today, and it occurs in the Arctic region; in North America, it is only found around the coastline of Alaska.

The early pinniped Enaliarctos. Left: Jaw from the Oligocene Yaquina formation of Oregon. Photo of UCMP V 253400 by Patricia Holroyd (University of California Museum of Paleontology/UCMP, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and scale added). Right: Reconstruction of Enaliarctos mealsi by Nobu Tamura (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Skeleton of the early pinniped Enaliarctos mealsi, Miocene Jewett Sand Formation, Kern County, California. The ruler at the bottom of the image is 1 meter long (39.4 inches long). Photo of USNM PAL 374272 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Skull of a tuskless walrus (Titanotaria orangesis), Miocene Capistrano Formation, Orange County, California. Source: Figure 5 from Magallanes et al. (2018) PeerJ 6: e5708 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Cast (reproduction) of a skull of a four-tusked walrus (Gomphotaria pugnax), Miocene, California. Specimen on temporary display at the Alaska State Museum, Juneau, 2019. Photo by Jonathan R. Hendricks (Earth@Home).

Lower jawbones of four species of Miocene walruses from the West Coast. A. Pelagiarctos, "Topanga" Formation, Orange County, California. B. Imagotaria downsi, Santa Margarita Sandstone, Santa Cruz County, California. C. Proneotherium repenningi, Astoria Formation, Lincoln County, Oregon. D. Pontolis magnus, Empire Formation, Coos County, Oregon. Source (figure and adapted caption): Figure 7 from R. W. Boessenecker and M. Churchill (2013) PLoS ONE 8(1): e54311 (Creative Commons Attribution license, image resized).

Cenozoic aquatic and terrestrial fossils

Eocene Chuckanut Formation

The Eocene Chuckanut Formation outcrops on Sucia and Lummi islands off the coast of Washington. It also occurs in northwestern Washington near Bellingham and extends to the northeast, to near the boundary between the Pacific Border and the Cascade-Sierra Mountains regions.

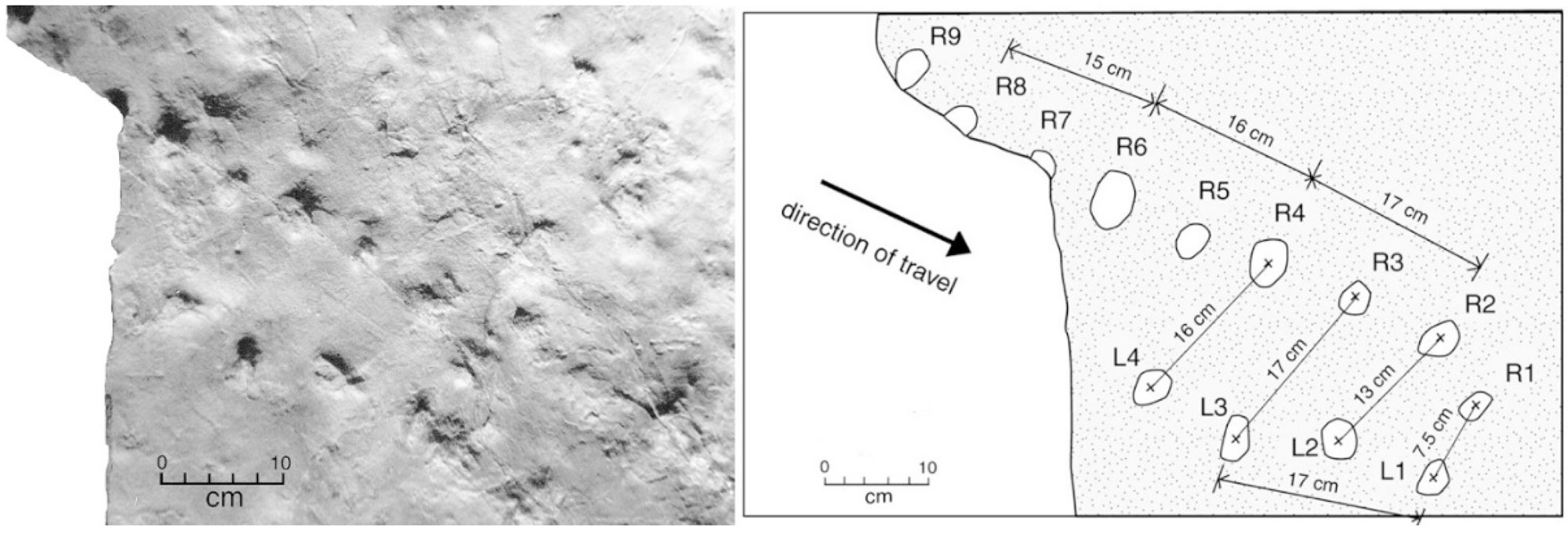

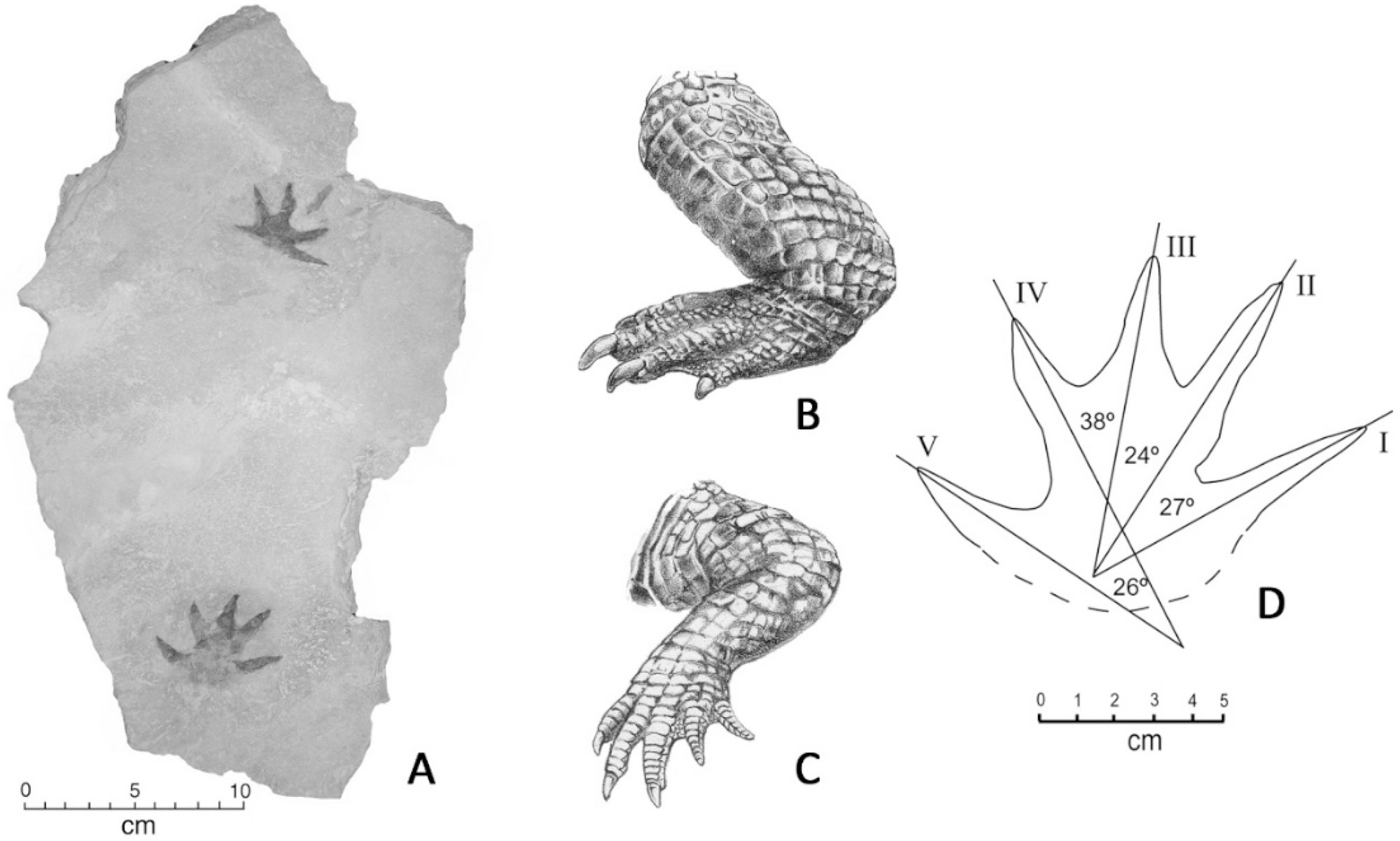

Aquatic animals of the Chuckanut Formation include freshwater gastropods and mussels as well as turtles. Mammal and bird tracks are also preserved. Plant fossils include horsetails (Equisetum) associated with animal trackways, spectacular impressions of fan-like palm leaves, and other angiosperms, ferns, and conifers.

A turtle trackway Eocene Chuckanut Formation, Whatcom County, Washington. Left is a photo of the trackway, right is an illustration interpreting the trackway (R = right legs, L = left legs). Source: From Figure 7 in Mustoe (2019) Geosciences 9(7): 321 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Crocodilian footprints (left), Eocene Chuckanut Formation, Whatcom County, Washington. The drawings in the center show modern crocodile feet; the drawing at the right is an outline of one of the fossil tracks with measurements. Source: From Figure 9 in Mustoe (2019) Geosciences 9(7): 321 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Impressions of fossil palm leaves (Sabalites), Eocene Chuckanut Formation, Whatcom County, Washington. Source: From Figure 4 in Mustoe (2019) Geosciences 9(7): 321 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Unidentified angiosperm leaf, Eocene Chuckanut Formation, Whatcom Creek, Washington. Photo of YPM PB 064582 by Linda S. Klise (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Desmostylians

Desmostylians are a group of enigmatic Oligocene to Miocene mammals that looked like and probably lived in similar habitats to modern hippos. Desmostylians are found only around the northern edges of the Pacific Ocean. In the eastern Pacific, they are found on the West Coast of North America from the Aleutian Islands in Alaska to Baja California Sur in Mexico. The modern relatives of these animals are unknown. The first desmostylian fossils were found in the 1800s in Alameda County, California.

Three views of a desmostylian tooth (Desmostylus hesperus) from the Miocene Temblor Formation, Fresno County, California. Photos of specimen UCMP 136511 by Sarah Rieboldt (University of California Museum of Paleontology/UMCP, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, images cropped).

Reconstruction of a desmostylian (Desmostylus hesperus) on the shore. Illustration by Dmitry Bogdanov (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license).

Quaternary fossils

La Brea Tar Pits

During the Pleistocene, large terrestrial mammals were common, including mammoths, woolly rhinos, horses, camels, bison, saber-toothed cats, and dire wolves. The famous La Brea Tar Pits in downtown Los Angeles provide a spectacular window into the region’s Pleistocene mammal communities. The tar pits formed around 40,000 years ago, when natural asphalt deposits began to seep up from cracks in the ground to form pools. As this asphalt seeped from the ground, it became covered with leaves and dust. Animals that wandered in became trapped, as did predators that arrived to eat the mired animals.

The oldest remains from La Brea have been dated to 38,000 years old, and the tar pits still continue to trap unsuspecting animals today. Bones sink into the asphalt are stained dark brown or black, leading to the unique appearance of the fossils found here. Fossils of more than 600 species of animals and plants have been excavated from the asphalt. In addition to large mammals and birds, the tar pits have preserved a remarkable array of microfossils ranging from insects and leaves to pollen grains, seeds, and ancient dust.

Underside of the skull of a Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) called "Zed" at the George C. Page Museum, Los Angeles, California, 2014. This mammoth was discovered near the La Brea Tarpits during a construction project in 2006. Photo by Ian Abbott (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 generic license).

The skull of a dire wolf (Canis dirus), La Brea Tarpits, Pleistocene, Los Angeles, California. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Water scavenger beetles (Hydrophilius), Pleistocene, La Brea Tarpits, Los Angeles, California. Photo by Didier Descouens (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 international license, image cropped).

The saber-toothed cat

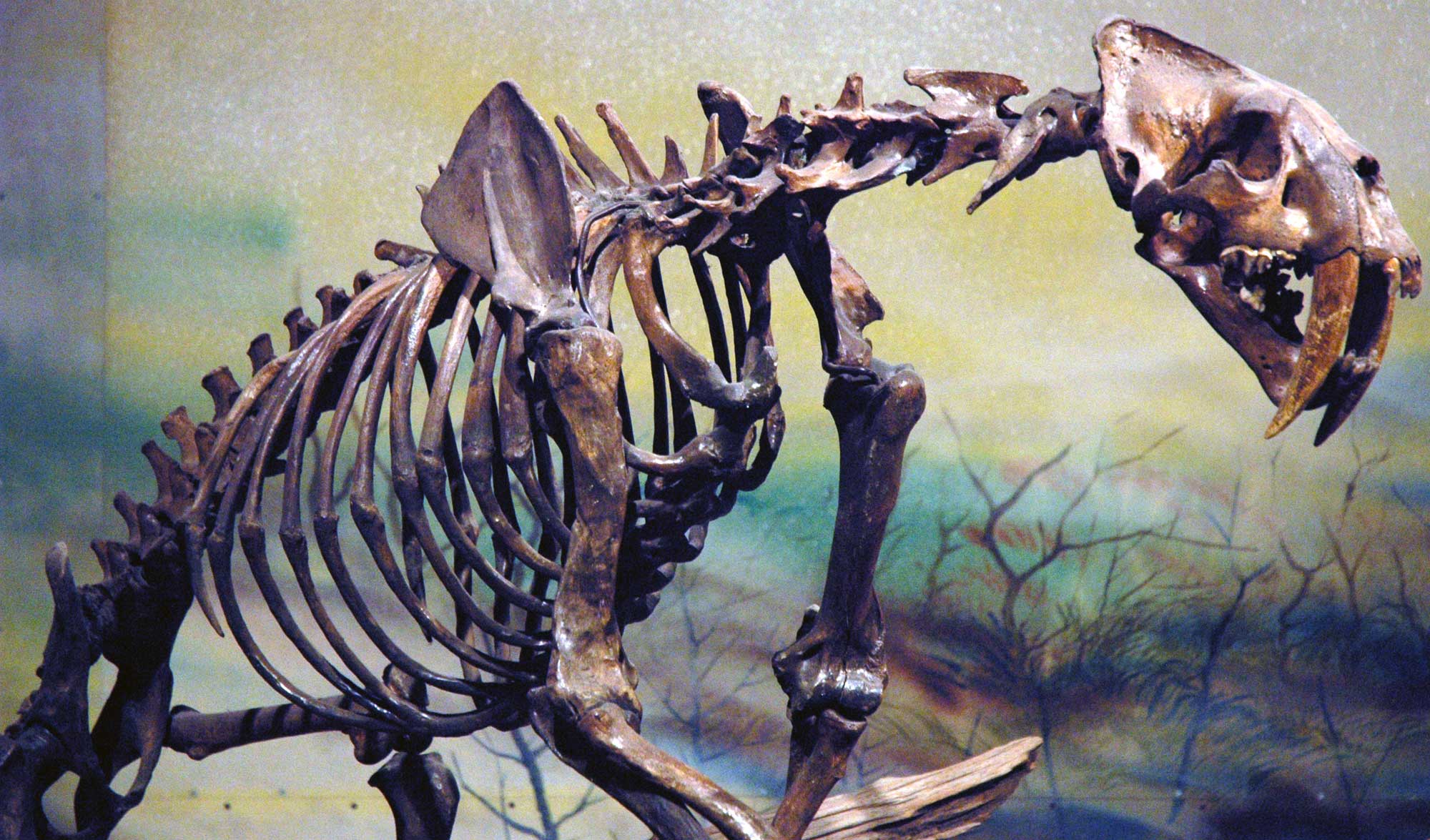

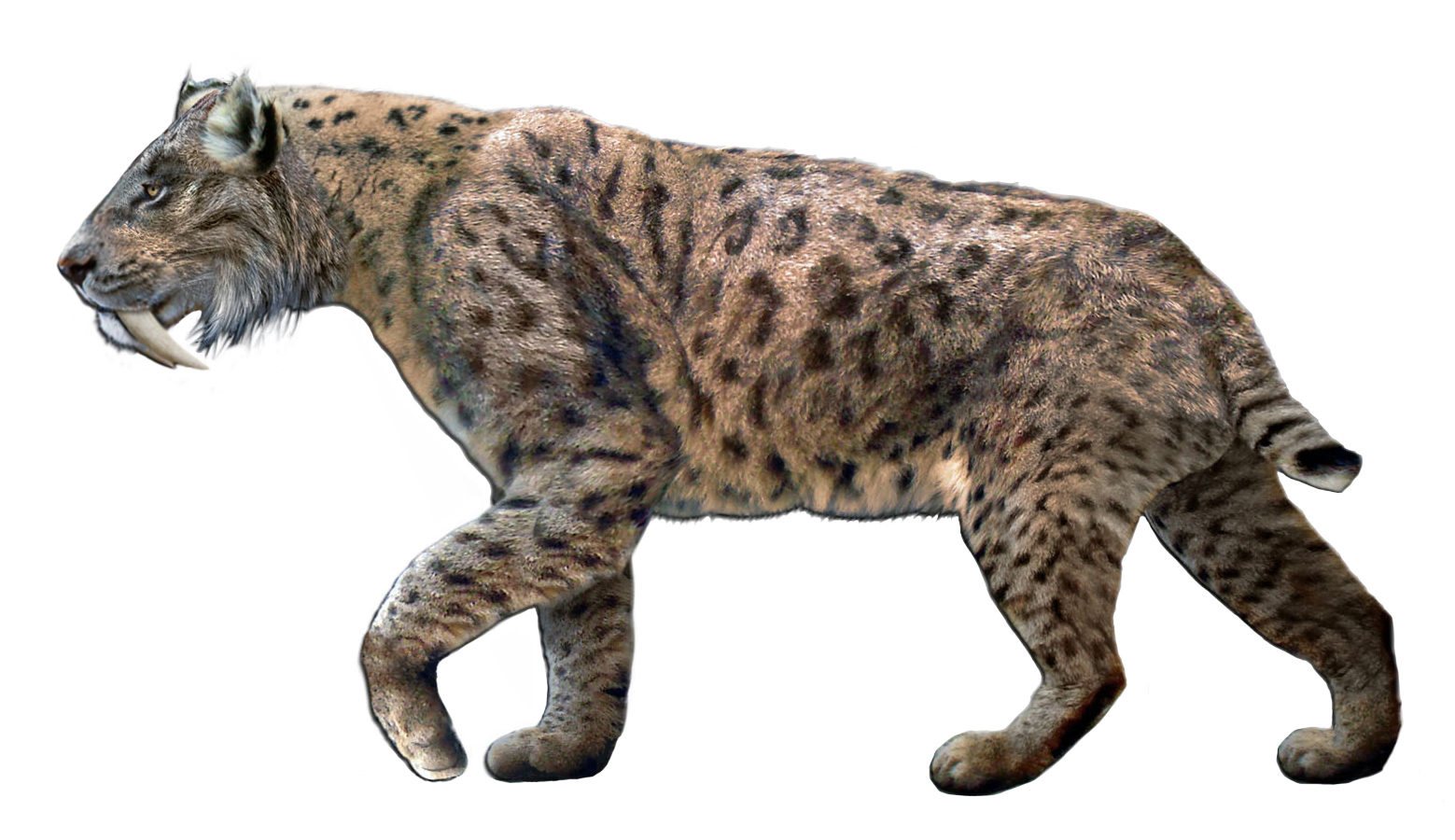

Smilodon fatalis, the saber-toothed cat, is among the most famous species represented in the La Brea Tar Pits. This extinct big cat is well known for its prominently elongated canine teeth. While these animals are sometimes referred to as “saber-toothed tigers,” they are not actually close relatives of tigers or any other living feline group. Smilodon belongs to the group known as “dirk-toothed” cats, which possess teeth with fine serrations.

The elongated canines of Smilodon were fairly thin and would have broken if they bit into bone, so these teeth would likely have been used to kill prey that was already subdued. The cats’ most common prey were likely bison and camels; dire wolves were probably their direct competitors.

Smilodon went extinct around 10,000 years ago, along with many of the large mammals it utilized for food. These extinctions have been related to both climate change and hunting by humans, although the relative importance of each of these factors is still debated.

Skeleton of a saber-tooth cat (Smilodon fatalis), La Brea Tarpits, Pleistocene, Los Angeles, California. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Illustration of a saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis) by Dantheman9758 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license).

The Pacific mastodon

In 2019, scientists named a new species of mastodon: the Pacific mastodon (Mammut pacificus). This mastodon species is similar to the more widespread American mastodon (Mammut americanum). The differences between the two species are subtle, such as the shape of the molars and the number of vertebrae making up the end of the backbone. The Pacific mastodon has been found only in California (including the La Brea Tarpits and many other sites), southeastern Idaho, and Montana.

Skull of a Pacific mastodon (Mammut pacificus) from the Pleistocene of Riverside, California. Source: Figure 7 from Dooley et al. (2019) Peer J 7:e6614(Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, label added and image resized).

Map showing the distribution of the Pacific mastodon (red dots) and the locations of selected American mastodon specimens (blue dots) that were used for comparison in a study. Source: Figure 4 from Dooley et al. (2020) Peer J 8: e10030 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

The Channel Islands pygmy mammoth

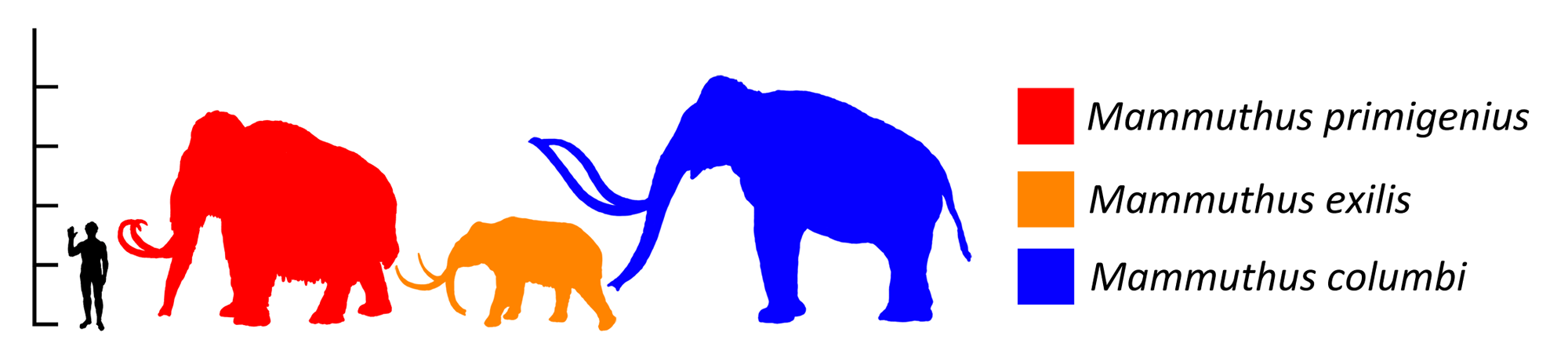

During the Pleistocene, the large Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) ranged throughout most of the contiguous 48 U.S. states and into Mexico. A much smaller species of mammoth, the pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis), was found only on the Channel Islands of California.

The Channel Islands are a group of islands off the coast of southern California near Los Angeles and Ventura. When sea levels were lower during the Pleistocene, the Channel Islands were colonized by Columbian mammoths, which are thought to have swum from mainland California over 80,000 years ago. At their largest, Columbian mammoths were more than 4 meters tall (up to 14 feet, measured at the shoulder). Over generations, the mammoths on the Channel Islands became smaller, eventually evolving into pygmy mammoths. At their largest, pygmy mammoths stood perhaps 2.4 meters (8 feet) tall.

The Channel Islands pygmy mammoths went extinct near the end of the Pleistocene epoch. Humans had reached the islands by that time. Bones of a person known as Arlington Springs Man were discovered on the Channel Islands in the 1950s and later dated to about 13,000 years old. The remains of Arlington Springs Man are among the oldest known human bones discovered in North America.

Size comparison of the three types of mammoths found in the Pleistocene of North America. Diagram modified by a diagram by FunkMunk (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Pygmy mammoth (Mammoth exilis) from the Pleistocene, Channel Islands National Park, California. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Pygmy mammoth (Mammoth exilis) being excavated. Pleistocene, Channel Islands National Park, California. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Daring to Dig: Annie Alexander: https://www.museumoftheearth.org/daring-to-dig/bio/alexander (More about Annie Alexander, who Thalattosaurus alexandrae was named after)

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/