Chapter Contents

- Apocalyptic Tales of Climate Change

- Use of Language and Perspective in Teaching Climate Change

- Hope and Optimism

- Considerations of Fear, Anxiety, and Mental Health

- Apocalyptic Prophesies Versus Predictions of Climate Change

- Reality Check: A Personal Perspective

- Science Teaching Toward a Sustainable World

- Resources

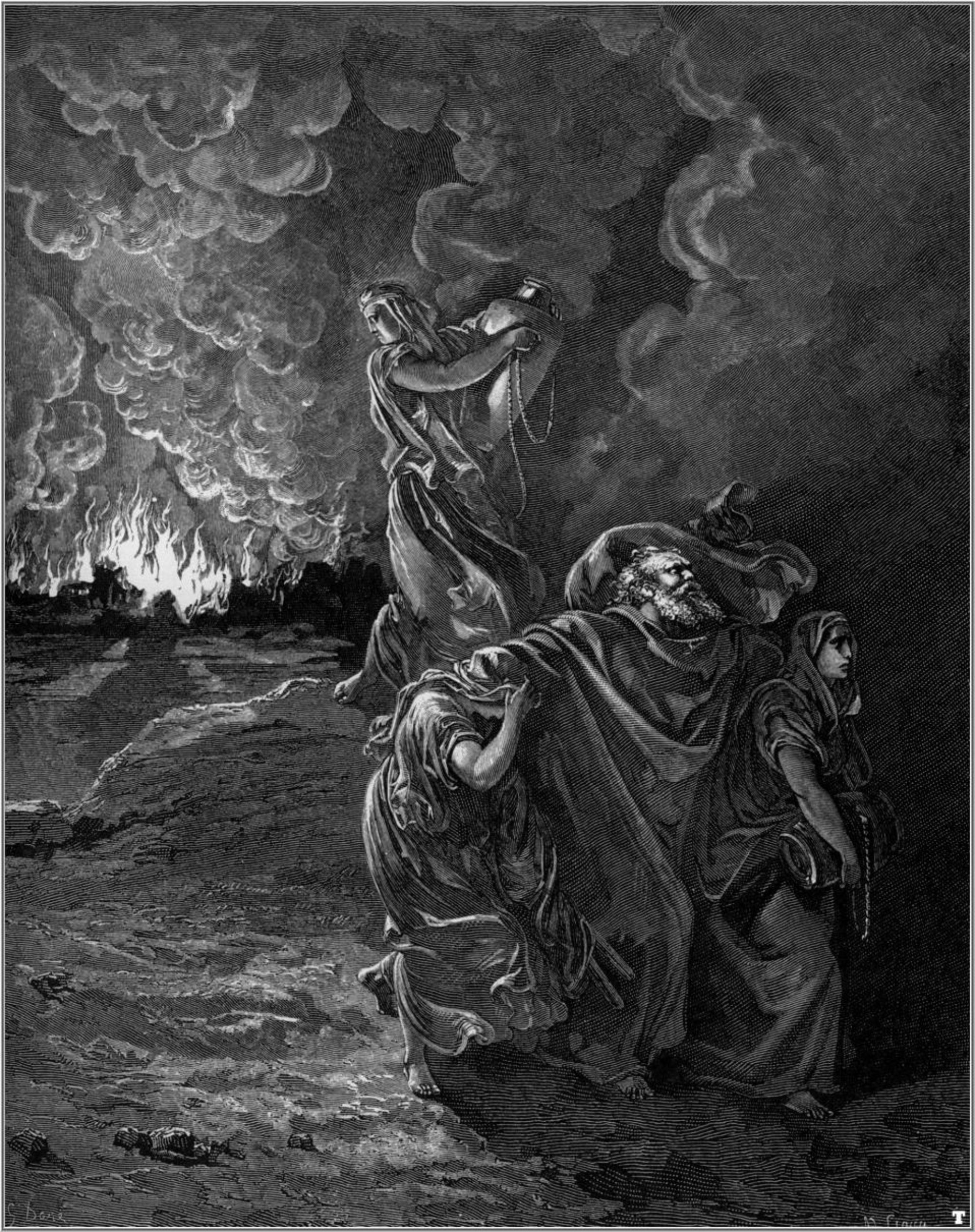

Image above: Queen Mary Apocalypse, 14th century, unknown artist, public domain license via Wikimedia Commons

In polarizing issues, apocalyptic rhetoric is often found at both poles of the issue in question. The extremes related to climate change are destruction of the environment and civilization (or even the entire Earth) at one extreme and destruction of the economy, freedom, and the “American way of life” at the other.

We’ve been telling stories of apocalypse and of lost Edens as long as we’ve been telling stories. Such tales are engaging, memorable, instructive, and motivating. Note that the loss of a past ideal state and the destruction of the current state are different but sometimes related ways of expressing regret or fear of significant negative change. For the sake of readability, these are lumped together in this chapter as “apocalyptic tales.”

Environmental educators and advocates have been telling modern versions of these tales for generations for the same reasons that other folks have told them for millennia. From the Book of Genesis to The Lorax (a children’s book by Dr. Seuss about the destruction of the environment through corporate greed, published in 1971 during a rise in public environmental awareness), humans are drawn to stories of paradise lost. And they learn from them too.

Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring—a book that had an enormous effect on the growth and awareness of environmental sciences—helped to usher in an era of environmental apocalyptic writing and reporting, and those stories were fundamental to cleaning up our environment. About the same time, predictions were being made by scientists and reported on by the media—predictions that, metaphorically, looked a lot like biblical visions of fire and brimstone from the Book of Revelation. The villainous actions were readily visible: flammable chemical wastes dumped directly into rivers, and black smoke billowing out of smokestacks, rivers catching fire, and cities being shrouded in smog and smoke. A recent example is the fires around Fort McMurray, Alberta (Canada), where forest fires associated with record heat surrounded the strip-mined landscape containing the Athabasca tar sands and its piles of waste sulfur.

Al Gore and Bill Nye are examples of many who point out the urgency and apocalyptic outcomes of rapid climate change. While they’ve both done great work and deepened the understandings of millions of Americans, they’ve simultaneously unintentionally deepened the convictions of millions who reject the scientific consensus on climate change. The reasons for these mixed outcomes are complex, but at least one may be the apocalyptic storylines associated with their messages. Al Gore is also seen as a political partisan and is instantly polarizing for many, regardless of what he says (what he says is generally well aligned with the consensus of scientists). Bill Nye is increasingly seen in the same light.

Real life fire and brimstone

Among many stories of environmental degradation going on today, one of the more symbolic of apocalyptic “fire and brimstone” is the stunning 2016 fires around Fort McMurray, Alberta. The fires began burning on May 2 and were declared under control on July 5. It continued to smolder until the last embers were extinguished in August of 2017. The site is the largest area for oil (“tar”) sands development in the world. To mine the tar sands several hundred square miles of surface boreal bogs are removed for open-pit mining.

Fort McMurray is the town adjacent to the oil sands production facility (and production waste). Producing oil from tar sands is more energy intensive than other forms of oil production. That means it produces more greenhouse gases per barrel of oil than other means. And in an Earth system irony, it may be that the likelihood of drought-induced fires in the Canadian Rockies was increased by climate change associated with carbon emissions—less snowpack than typical and record setting temperatures of about 90 °F (32 °C), low humidity, and high winds.

Production of oil from oil sands also produces another byproduct in huge quantities—sulfur. The largest pyramids in the world are not in Egypt or made of cut stone. They are near Fort McMurray and made of sulfur from tar sands development. Brimstone is a stone—sulfur—that forms at the brim of a volcano. Though some sulfur is sold for commercial use, in Fort McMurray, it accumulates much faster than it’s used.

The Fort McMurray fire was the costliest disaster in Canadian history, and forced the evacuation of 90,000 people, also the largest in Canadian history. The fires were associated with over 2400 burned structures, extensive burned forest, and weeks of halted oil sands production. The fire and brimstone together had the ingredients of a biblical apocalypse.