Credits

By Robert Ross and Warren Allmon, Paleontological Research Institution.

Page last updated April 27, 2022.

Image above: Cascadilla Gorge in autumn. Photograph by Robert Ross.

Cascadilla Gorge

Cascadilla Gorge is located in Ithaca, New York. Cascadilla Creek flows from the east, along the south side of the Cornell University campus, passing Collegetown, and tumbles 400 feet down Cascadilla Gorge to downtown Ithaca. During the warm weather months, you can follow a trail that hugs the creek and examine the spectacular cliff walls along the way.

Upper part of Cascadilla gorge, facing the College Avenue bridge. Photograph by Warren Allmon.

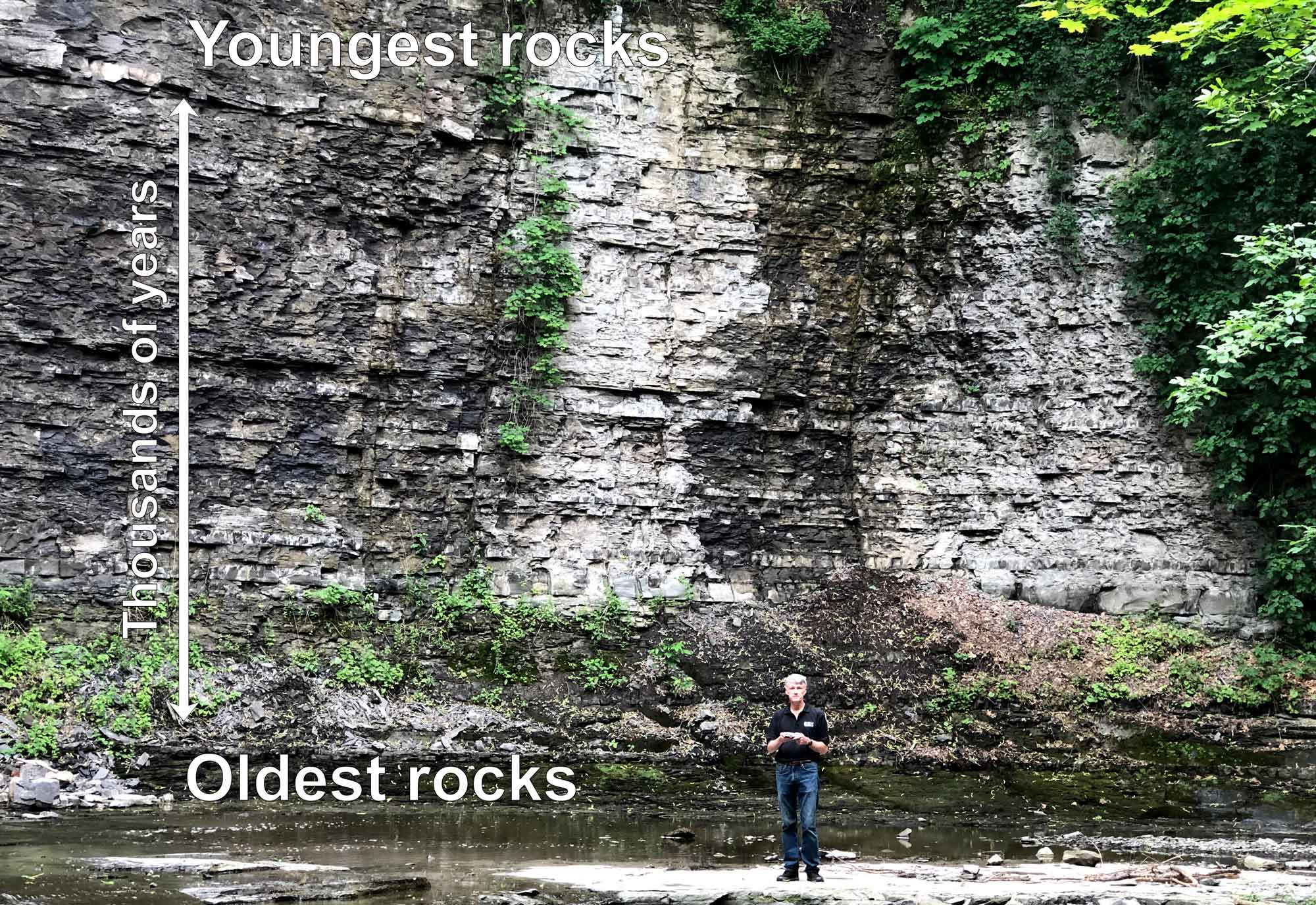

Cascadilla Gorge exposes thousands of thin rock layers made of fine sand, silt, and mud. Because layers of sediment form one upon another, a process we can watch in water bodies today, we know that the oldest layers are at the bottom. This idea is known as the principle of superposition. The profound implications are that we can read the history of the Earth by investigating each successive layer, from bottom to top. The kind of sediment, fossils, and other features in each layer tell geologists about the environment in which that sediment settled.

Devonian-aged rocks in Cascadilla Gorge illustrate the principle of superposition. Photograph by Robert Ross.

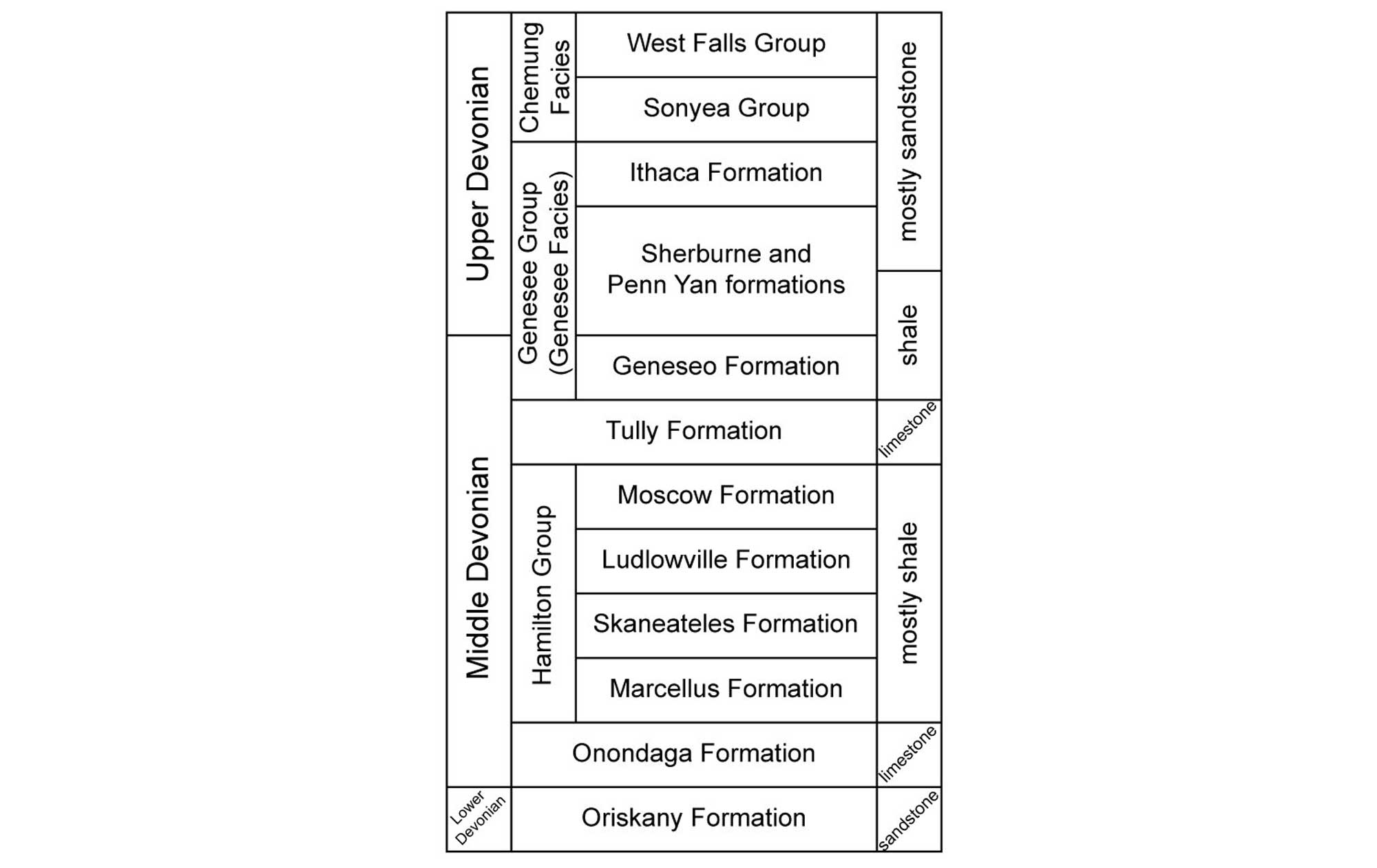

The rocks of Cascadilla Gorge were deposited in the Late Devonian Period, about 370 million years ago, similar in age to the layers in other gorges around the southern edge of Cayuga Lake. The particular rocks exposed in Cascadilla Gorge are from rocks known as the Ithaca Formation, and rocks in the gorge were among those first used by geologists to define local rock units. In fact, the "Cascadilla Member" is a subsection of the Ithaca Formation that is defined by the rocks found in Cascadilla gorge between its base in downtown Ithaca and its top in Collegetown.

Stratigraphy of Devonian rocks in the Finger Lakes region; the oldest rocks are at the bottom. Source: Fig. 1.3 in Gorges History by Arthur Bloom (published in 2018 by the Paleontological Research Institution). Copyright Paleontological Research Institution.

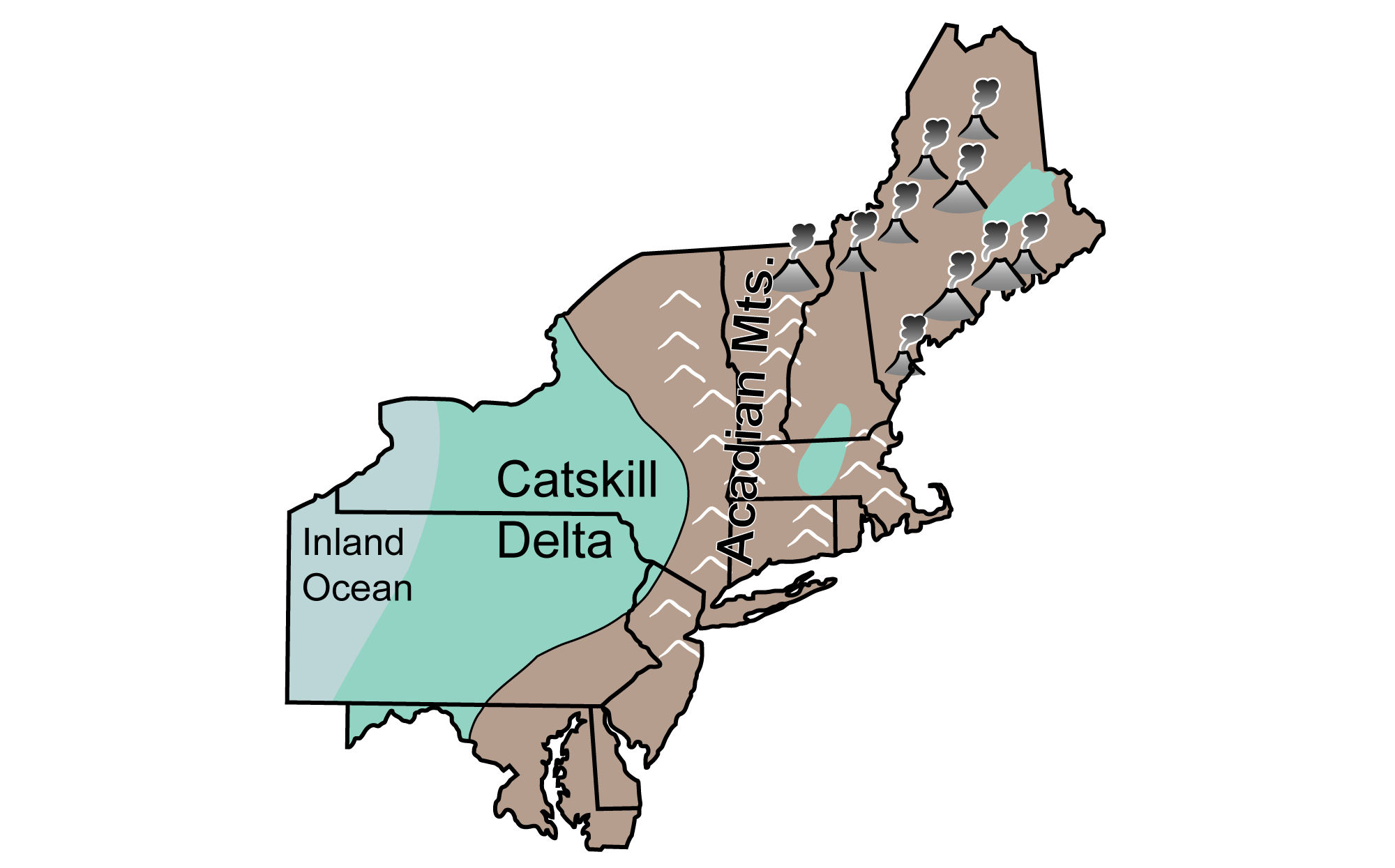

The silt and mud that make up these rocks eroded off of a mountain range to the east, which geologists call the Acadian Mountains (precursors to the modern Appalachian Mountains). West of those mountains the land was subtly buckled downward, forming a long narrow depression we call the Appalachian Basin. Sea level was high enough fill the Appalachian Basin with a shallow inland sea.

Highly simplified reconstruction of the northeastern United States during the Devonian Period. Most of the rocks in the Finger Lakes Region were formed from sediments shed from the ancient Acadian Mountains into the Catskill Delta to the west. Image modified from original by J. Houghton first published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Northeastern U.S. by Jane Ansley (published by the Paleontological Research Institution) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Many of the layers you can observe in Cascadilla Gorge were deposited quickly when sediment-laden water swept westward down the slope of the ancient Catskill Delta. These layers have coarser grains at the bottom, which settled first, followed by finer grains, including clay, on top.

A graduated cylinder holds several layers of sediment spilled into water. Each of the layers contains coarser grains at the bottom and progressively finder grains upward. Demonstration by Alexandra Moore; photograph by Robert Ross.

The rocks made of coarser grains such as fine sand and silt tend to be more weathering-resistant and stick out of the cliff, relative to the muddy layers with substantial clay, which are softer and weathered back into the cliff.

Coarser-grained layers of siltstone are harder and more weathering-resistant than clay-rich layers of softer shale between them. Photograph by Robert Ross.

Most of the rocks in Cascadilla Gorge do not have especially abundant fossils (some other layers in Central New York are famous for their fossils), but if you look carefully, you may notice fossils in blocks or slabs of rock that have fallen off the cliff. Many of these fossils are the shells of marine creatures known as brachiopods.

Two slabs of siltstone containing abundant fossil brachiopods from Cascadilla Gorge. Photograph by Warren Allmon.

Brachiopods look like the clams you can find along beaches today, but in fact they are a very different kind of animal. We know they are different because we can find living brachiopods today, though they are not nearly as common as they once were. Brachiopods are one type of evidence by which we know that the Appalachian Basin was filled with sea water.

Like most topographic features, the age of the creek and gorge are very young compared to the rocks they cut through. The gorge has formed largely since the last time glacial ice sheets covered Ithaca, less than 20,000 years ago. The process was facilitated by weathering along pre-existing vertical cracks called "joints" that formed due to stresses during a mountain building event that occurred in the early Mesozoic Era.

Left: Weathering occurs more quickly along ancient vertical cracks that run through the rocks of Central New York (photograph by Robert Ross). Right: A large rounded granite boulder (foreground) sits in the middle of Cascadilla Gorge, with the Collegetown bridge in the background. This boulder was carried here by glaciers, and dropped when the glaciers melted away from this part of central New York, around 20,000 years ago. Such boulders are called “glacial erratics” (photograph by Warren Allmon).

Cascadilla Gorge Video

Learn more about the geology of Cascadilla Gorge in this video.

"Cascadilla Gorge" by The Paleontological Research Institution (YouTube).

Learn and explore more

Poetry in America: "Cascadilla Falls" by A.R. Ammons

Cornell Chronicle: 'Ammons & the Falls' highlights poet's ties to Ithaca landscape

Earth@Home: