Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of Hawai'i.

Topics covered on this page: Types of Hawaiian fossils; How did organisms colonize Hawai'i?; Hawai'i before humans arrived; Arrival of humans and aftermath; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page comes from "Fossils of the Western US" by Brendan M. Anderson, Alexandra Moore, Gary Lewis, and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated June 22, 2022.

Image above: Unidentified gastropod (snail) shell from the Pleistocene of Honolulu County, O'ahu, Hawai'i. Photo of YPM IP 533438 by Jessica Utrup, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Types of Hawaiian fossils

Most fossils occur in sedimentary rocks, but almost all of Hawai'i consists of igneous rock. Nevertheless, Hawai'i does have a fossil record, and most of these fossils are often found in three unusual geological settings:

- Inside lava tubes or caves.

- In limestones formed by the coral reefs surrounding the islands, which, when exposed to the air (when sea level falls or the island is uplifted) can become karst.

- As charcoalified imprints of trees in or between lava flows.

Nāhuku (also called Thurston Lave Tube), a lava tube at Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, Big Island (Hawai'i), Hawaiian Islands. Photo by J. Wei, NPS (National Park Service/NPS, public domain).

Subfossils

Many of the organic remains described from Hawai'i can be called subfossils. Subfossils are remains or traces of past life that are less than 10,000 years old, which is the standard (though arbitrary) age definition for fossils. In practice, such materials are treated like “true” fossils and provide the same kinds of information.

The fossil record of the Hawaiian Islands preserves a 400,000-year history of island biodiversity. Fossils of plants, birds, fish, terrestrial and marine invertebrates, and a lone native terrestrial mammal paint a picture of surprisingly diverse Hawaiian ecosystems prior to the arrival of the first humans.

Bones of a high-billed crow (Corvus impluviatus), a bird that was endemic to the Hawaiian Islands but that went extinct after humans arrived. Specimen from the Cenozoic (near-recent) of O'ahu. Photo by Mark Florence (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Trace fossils

Trace fossils in Hawai'i are most often represented by the trunks and branches of trees that have been consumed by molten lava. When lava flows through a forested area, the molten liquid chills and solidifies almost instantly when it comes in contact with large vegetation. The lava is still quite hot—enough to ignite and burn the trees, leaving behind a mold of the former tree trunk. Lava flows commonly deflate and subside after solidification, and tree molds can protrude above the frozen surface of the flow, leaving behind “lava trees.”

Lava consuming a tree, Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, Big Island of Hawai'i. Photo by Marius Arigot, NPS (National Park Service/NPS, public domain).

Tree mold, Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, Big Island of Hawai'i. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Marine fossils

Marine fossils in Hawai‘i are not widespread, but can be very abundant where they do occur, along the coasts of Kaua'i, O'ahu, Molokai, Lanai, and Maui. All are found in limestones formed by uplifted Pleistocene or Holocene coral reefs and can be studied either from coastal outcrops or from cores taken by ship. More than 150 species of mollusks (bivalves and gastropods) have been reported in these reef limestones, together with numerous fossil corals.

Fossil Hawaiian top shells (Turbo sandwicensis) from O'ahu, age not specified. Photo by David Eickhoff (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

How did organisms colonize Hawai'i?

As the most isolated archipelago in the world, the Hawaiian Islands were colonized by a relatively small number of species that could successfully disperse across the ocean by flying, floating, or being blown by wind. Most plants arrived as seeds carried by migratory birds, either carried in the birds' stomachs or stuck to their feathers or skin. A smaller number of organisms drifted on air or floated on plant matter in ocean currents.

Organisms that survived the voyage to Hawai'i and reproduced in their new environment were able to move into new ecological niches because there were few competitors for resources. The lack of competition gave rise to an adaptive radiation of species. An adaptive radiation is the creation of multiple new species from a colonizing ancestor. Long distance travel coupled with subsequent species radiation have given Hawai'i a very unusual and highly endemic group of organisms.

The long distance and duration of the trip to Hawai'i favored certain types of organisms and selected strongly against others. Thus, there are no native Hawaiian terrestrial reptiles and amphibians. There is only one terrestrial mammal, the 'ōpe'ape'a or Hawaiian hoary bat. In contrast, there are many native species of birds, terrestrial invertebrates, and plants. Even in the marine realm, the abundance of species is skewed toward those that could travel across the open ocean, and a similar adaptive radiation occurred following the arrival of early nearshore reef species.

A Hawaiian hoary bat, Maui, 2010. Photo by Forest & Kim Starr (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States license, image cropped and resized).

A nēnē or Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis), Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, Kaua'i. Photo by Jörg Hempel (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany license, image cropped).

Shells of the land snail Endodonta, a genus of snails found only in Hawai'i. These specimens are from the Pleistocene of Honolulu County, O'ahu. Photo of YPM IP 533448 by Jessica Utrup, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

'Ahinahina or silverswords (Argyroxiphium) at Haleakala National Park, Maui. Scientists think that the silverswords descended from a California tarweed that reached the Hawaiian Islands over 5 million years ago. Photo by A. Rulison, NPS (National Park Service, public domain).

Hawai'i before humans arrived

Before the introduction of continental species by humans, Hawaiian terrestrial ecosystems lacked grazing mammals and were inhabited by large and often flightless grazing ducks and geese. The top predators were raptors (predatory birds). Plants lost certain defenses needed to guard against large grazing mammals. Carnivorous caterpillars (Eupithecia monticolens) evolved in Hawaiian forests. Nectar-sipping Hawaiian birds like the 'i'iwi (Vestiaria coccinea) coevolved with flowering plants and served as pollinators for some of them, like the endemic lobeliads and the 'ōhi'a lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha).

In addition to extinct species, many species of living plants and animals found in the fossil record no longer grow at low elevation; rather, they are found only in high-elevation refuges in remote parts of the islands.

An 'i'iwi, a type of Hawaiian honeycreeper, on a 'ōhi'a lehua tree in Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge, Big Island of Hawai'i. Photo by USFWS-Pacific Region (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Curved flowers of koli'i (Trematolobelia kaalae) a lobeliad that grows in the Wai'anae Mountains, O'ahu. These flowers are presumably adapted for pollination by birds with curved beaks, although this has not been established with certainty. Photo by David Eickhoff (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Ulupau Crater

The oldest terrestrial fossils in Hawai'i are found in lake sediments at the bottom of Ulupau crater on O'ahu. This fossil occurrence is an unusual one for Hawai'i and does not fall into one of the three more common modes of preservation described above. The island does not have many lakes, as its base is made up of porous lava. Eleven species of extinct birds have been identified there, dating to 400,000 years ago.

Makauwahi Cave

The richest fossil site in the islands is Makauwahi Cave on Kaua'i. Makauwahi is a karstic cave system in limestone containing a sinkhole lake in which sediments have accumulated over the last 10,000 years, providing excellent preservation. The hundreds of fossil organisms identified at Makauwahi include more than 40 species of birds (half of which are now extinct), 15 or more species of native land snails (all now extinct), and scores of endemic plants. One of the most curious species of bird is the Kaua'i mole duck (Talpanas lippa), which had unusually small eyes but very large nerve passages to its bill. Paleontologists believe that the mole duck was nearly blind; it may have inhabited caves or was perhaps a nocturnal feeder.

Makauwahi Cave IIa, Kaua'i. Photo by Wolfram Burner (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Excavation pit at Makauwahi Cave, Kaua'i. Photo by Wolfram Burner (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Arrival of humans & aftermath

Arrival of Polynesians

Radiocarbon dating of specimens at Makauwahi Cave documents the arrival of humans and the continental species they introduced, as well as the relationship between these new arrivals and the native organisms. Human-caused extinctions began about 1000 years ago, after Polynesians settled in Hawai'i. Lowland birds, along with large flightless geese and ducks, were among the earliest extinctions. These species disappear from sedimentary layers shortly after the appearance of fossils of human-introduced Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) and other evidence of human habitation. Early settlers also introduced dogs and pigs to the Hawaiian Islands.

A Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans) in Haleakala National Park, Maui, 2014. Photo byForest & Kim Starr (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States license, image cropped and resized).

A feral pig (Sus scrofa) in Keālia Pond National Wildlife Refuge, Maui, 2019. Pigs were first introduced to Hawai'i by Polynesian settlers, and today's feral pigs are thought to be descendants of these early pigs. Photo by Anita Gould (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Subfossil bones of the O'ahu moa nalo (Thambetochen xanion), a flightless duck, Barbers Point sinkholes, O'ahu. This bird went extinct between the arrival of Polynesians and the later arrival of Europeans on the Hawaiian Islands. Photo by David Eickhoff (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

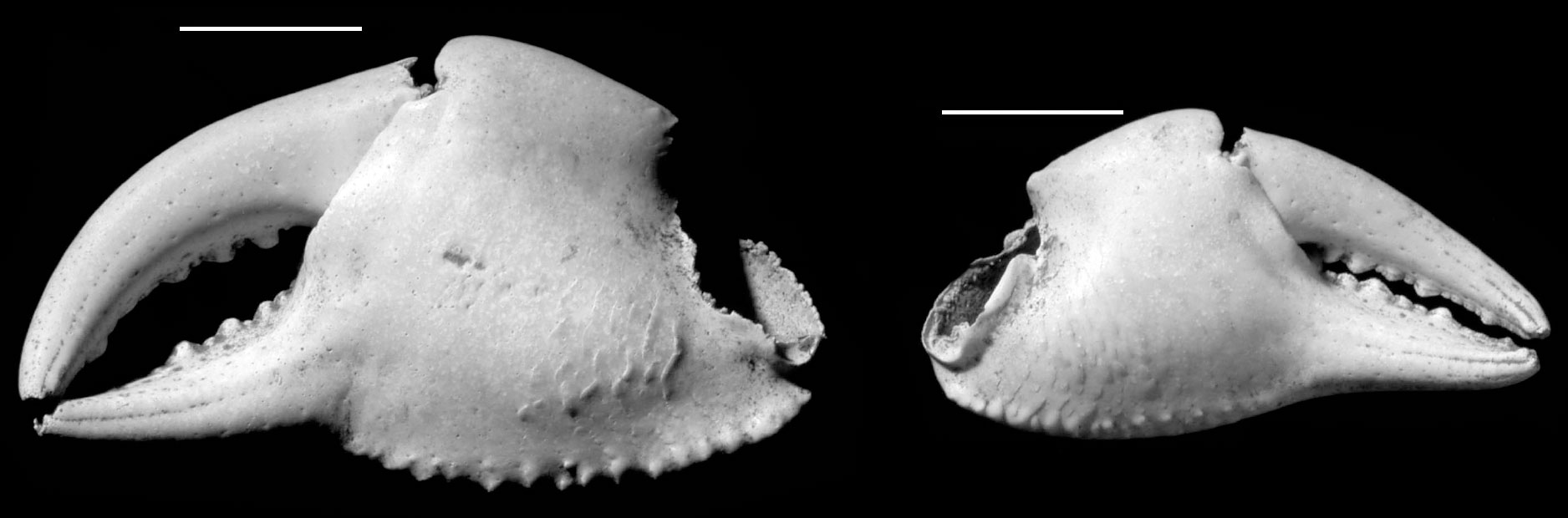

Claws of the land crab Geograpsus severnsi from Pu'u Naio Cave, Maui. Remains of Geograpsus severnsi have been found on Kaua'i and Maui, but the crabs vanished following human settlement of the islands. Scale bars = 1 centimeter (about 0.4 inches). Source: Images from Figure 1 in G. Paulay and J. Starmer (2011) PLoS ONE 6(5): e19916 (Creative Commons Attribution license, images cropped and reconfigured).

Late 1700s to today

Europeans first arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in the 1770s, and extinctions began accelerating soon thereafter. The extinction rate continues to increase even today. Factors include clearing of land for development and agriculture, the spread of diseases (for example, Avian malaria and Rapid 'Ōhi'a Death), and the impacts of introduced species like feral cats and pigs, mongooses, disease-carrying mosquitoes, and the aggressive tree miconia (Miconia calvescens).

Hawai'i’s highly diverse prehuman landscape is now completely transformed, with the decline or extirpation of most native species and their replacement with a small number of introduced species. For example, more than half of Kaua'i’s 140 historically described native bird species are now extinct.

A mongoose (Herpestes javanicus) on O'ahu, 2016. Mongooses were imported to Hawai'i in 1883 and released to control rats in sugar cane plantations. Photo by Tony Hisgett (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Shells of Carelia cochlea, a land snail found only on Kaua'i. This species probably went extinct in the 1800s. Photo by David Eickhoff (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Extinct Hawaiian honeyeaters. Left: Kaua'i 'ō'ō (Moho braccatus). This entire genus of birds (the 'ō'ō, genus Moho) is extinct, with different species disappearing between the 1830s and the 1980s. The Kaua'i 'ō'ō was the longest to survive, dying out around 1987. Right: Black mamo (Drepanis funerea). This species lived on Moloka'i and went extinct around 1907. Left and right paintings by John Gerrard Keulemans (via Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Loulu lelo or Moloka'i fan palm (Pritchardia hillebrandii) is one of about 19 species of loulu (Pritchardia, a group of palms) unique to the Hawaiian Islands. Feeding by goats, pigs, and rats has significantly reduced the wild populations of these palms. The palms above are growing on Huelo Islet (off Moloka'i), one of two islets with a remaining wild loulu lelo population. Photo by Forest Starr and Kim Starr (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/