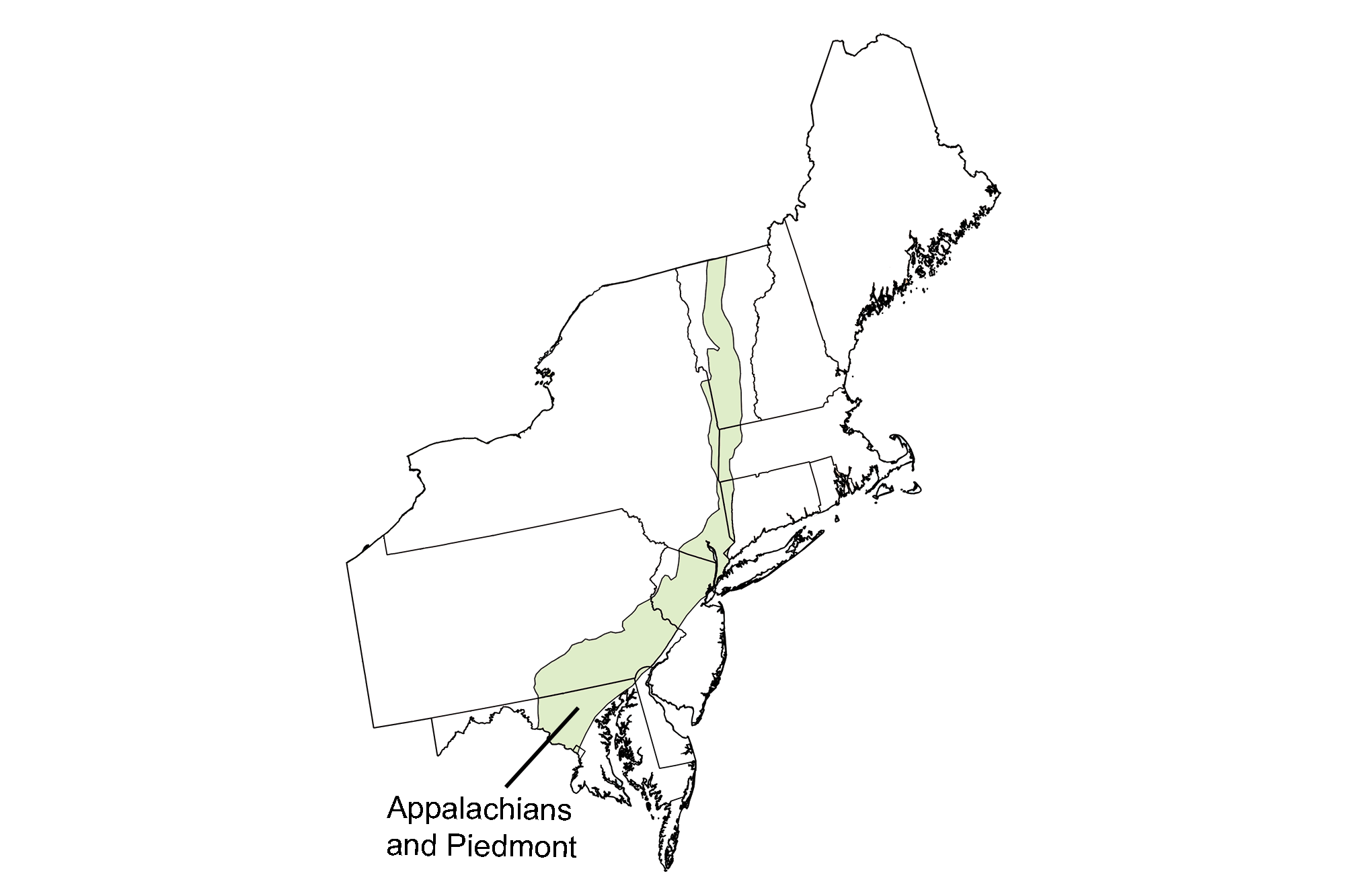

Spotlight: Overview of the fossils of the Appalachian and Piedmont region of the Northeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Paleozoic; Mesozoic; Pleistocene; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Rocks of the Northeastern US" by Jane Elizabeth Ansley, from The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US (published in 2000 by the Paleontological Research Institution, reprinted in 2016; currently out of print). The text was adapted for Earth@Home web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2023, with contributions to this page also by Warren Allmon. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 24, 2023.

Image above: Trilobite Olenellus thompsoni with preserved antennae from the Kinzers Formation of Pennsylvania. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Overview

The Paleozoic fossils in the Appalachian/Piedmont region are generally the same as those of the Inland Basin because the rocks were originally sediments deposited along the same inland ocean. The rocks of the Appalachian/Piedmont, however, are in general more deformed structurally because they were closer to or part of the Taconic, Acadian and Alleghanian mountain-building events. Because of the deformation, the fossils in this region are less well preserved. The Triassic and Jurassic age Rift Basin fossils, however, are only found in the Appalachian/Piedmont and the Exotic Terrane region.

Paleozoic fossils

Cambrian fossils

Cambrian rocks in the Appalachian/Piedmont record the erosion of sediment from the Grenville Mountains into the Iapetus Ocean. In southeastern Pennsylvania, the Emigsville Member of the Kinzers Formation contains an important Lower Cambrian lagerstätte deposit. The Kinzers Formation crops out in the Conestoga Valley, a complex succession of carbonates and siliciclastics in Lancaster and York counties. The exceptionally well preserved fossils occur in in a mixed siliciclastic-carbonate debris fan developed seaward of a carbonate shelf, which was subject to storm (tempestite) deposition. Most remains are fragmentary, but occasionally include complete bodies, especially of trilobites. The Kinzers Formation is interesting in that it appears to be a lagerstätte that was not associated with anoxia or abrupt salinity fluctuations, but rather with sudden burial that excluded predators and scavengers. The trilobite Olenellus can also be found in Cambrian rocks of western Vermont and northern New Jersey.

Late Cambrian stromatolites are found in Washington County, Maryland, and Bucks County, Pennsylvania. A spectacular outcrop of the Allentown Dolomite that contains well-preserved stromatolites occurs in the Borough of Hamburg, Sussex County, New Jersey. The Allentown Dolomite is Middle Cambrian to Lower Ordovician in age.

Front appendage of an anomalocaridid from the Kinzers Formation of Pennsylvania. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

An Early Cambrian trilobite (Olenellus) from Kinzers Formation, Pennsylvania. Photo of YPM IP 094005 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum, 2021 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Ordovician to Devonian fossils

There are some fossil-rich Ordovician and Silurian (and a few Devonian) sites in the Appalachian/Piedmont region, in spite of the deformation of the rocks from the various Paleozoic mountain-building events. For example, eastern Pennsylvania and western Vermont both preserve assemblages of brachiopods, trilobites, corals, bryozoans, clams, and other organisms typical of shallow marine environments.

A sea star (Swataria derstleri) from Ordovician Martinsburg Formation, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. Photo of YPM IP 527083 by Jessica Utrup, Yale Peabody Museum, 2014 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Mesozoic fossils

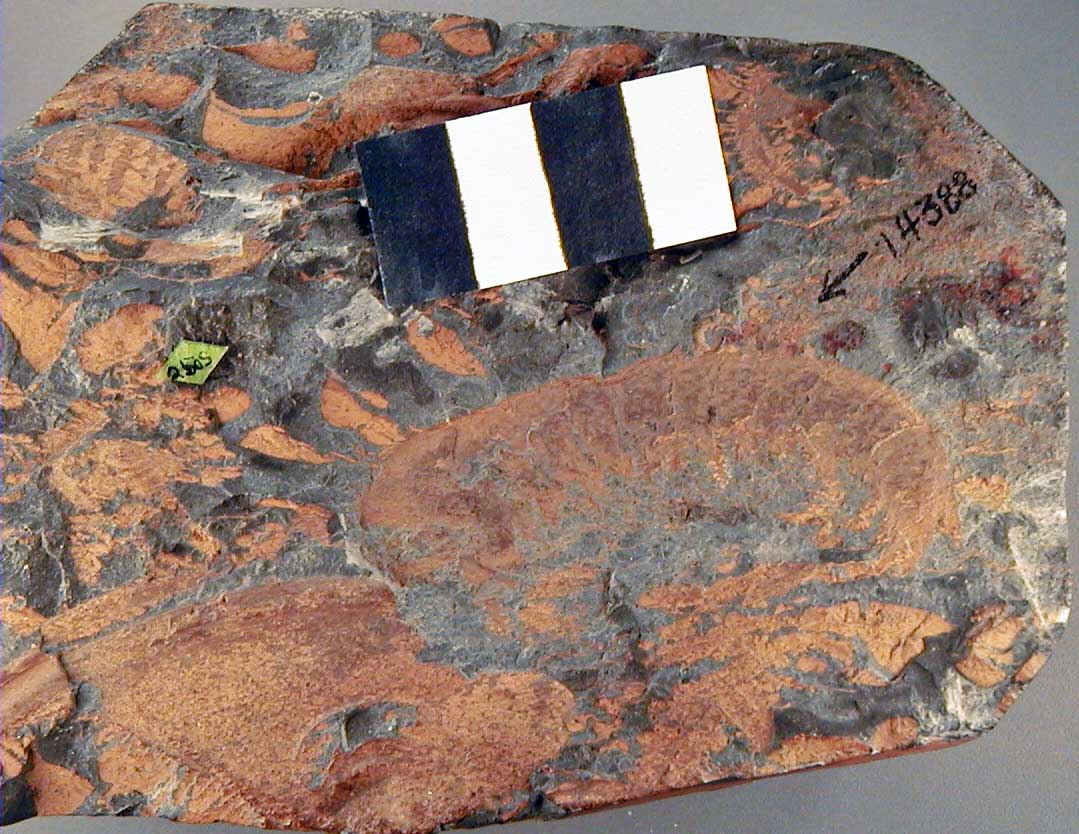

The Appalachian/Piedmont has extensive outcrops of Mesozoic rocks, preserved in the rift basins that formed when Pangea was breaking apart. The sedimentary rocks preserved in the rift basins record the presence of dinosaurs in the Northeast. In particular, the extensive dinosaur trackways found in these rocks have become among the most publicly known fossils in the Northeast. These deposits, which belong to the Newark Supergroup, are also found in the Exotic Terrane region of the Northeast and in Virginia and North Carolina in the Southeast.

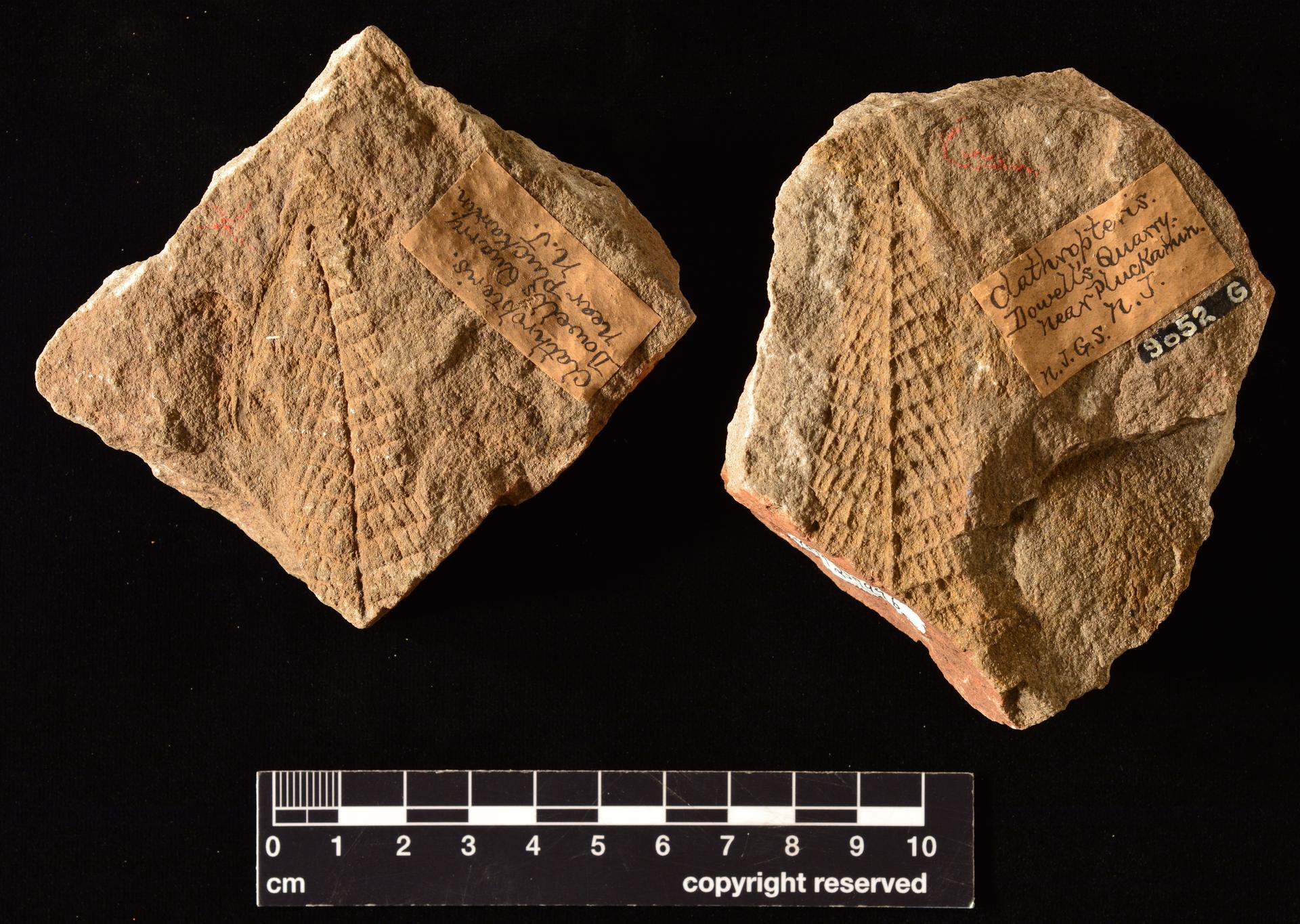

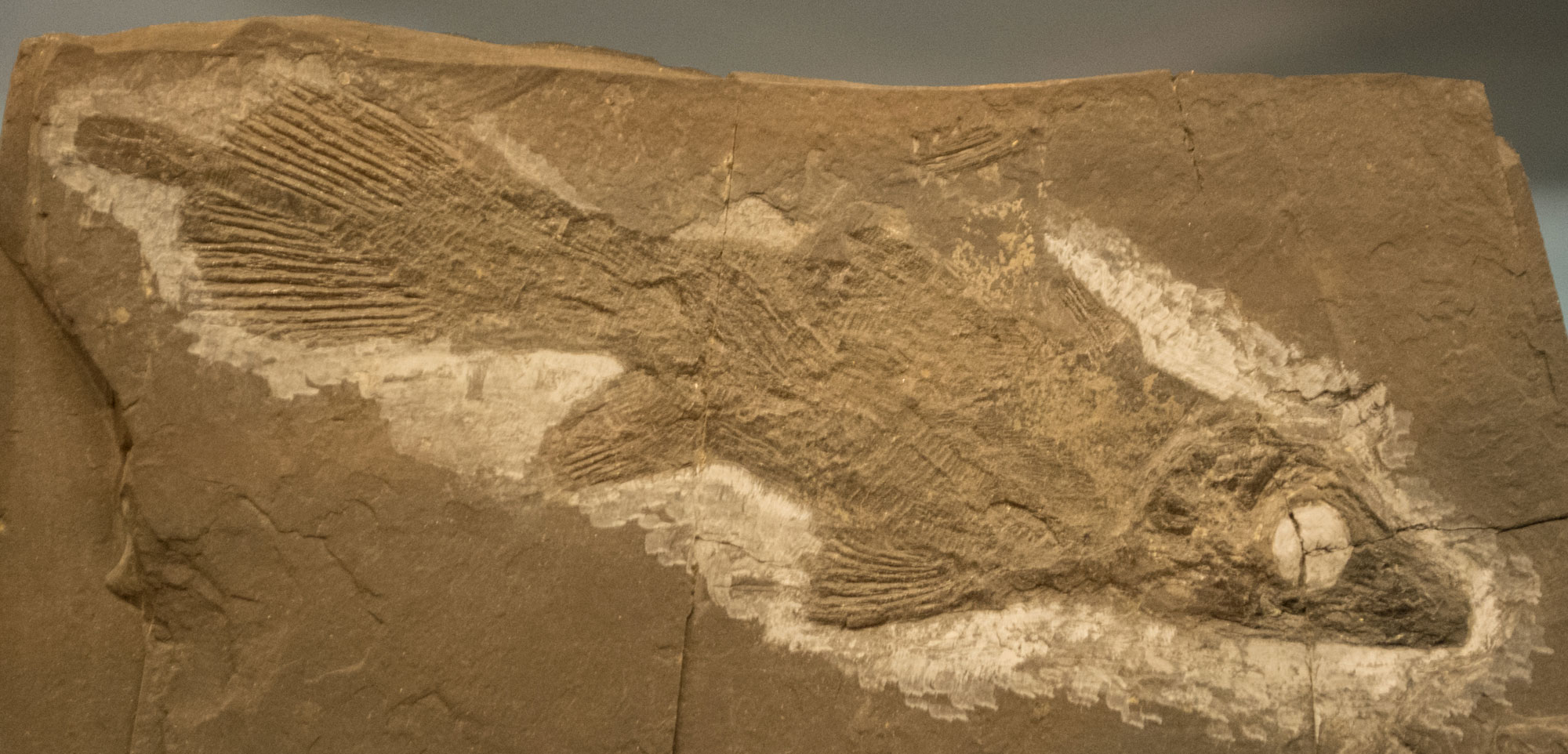

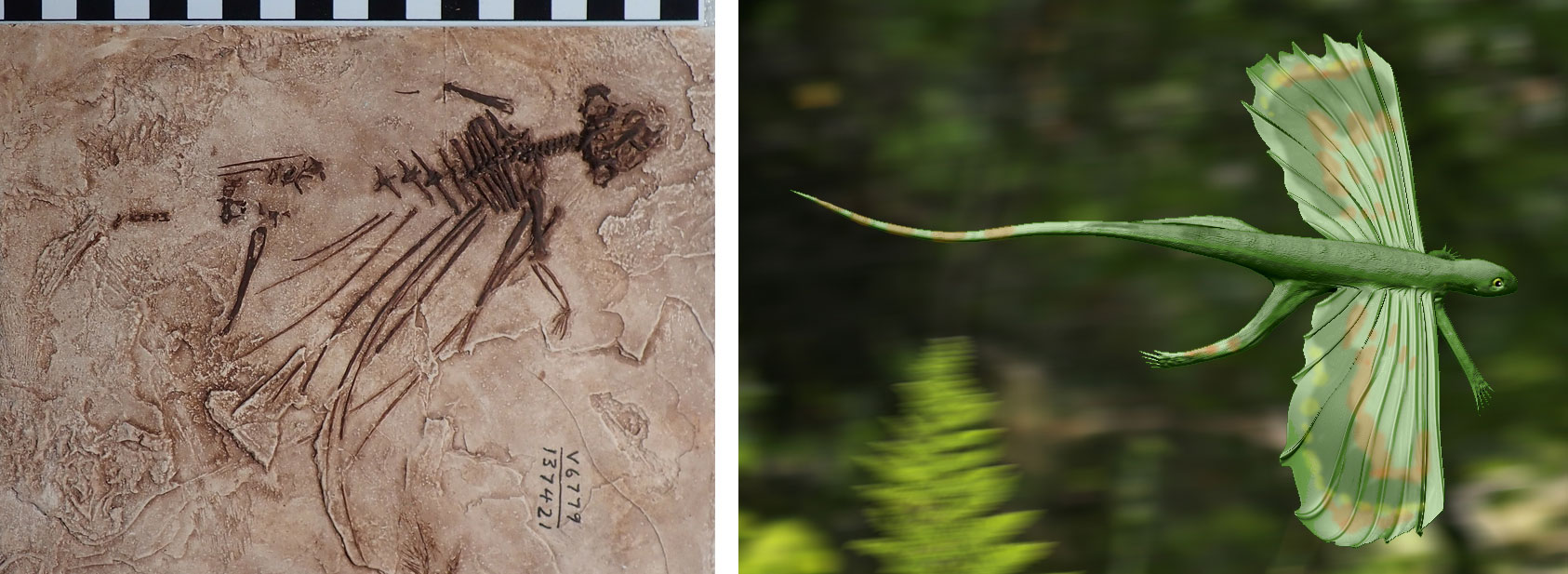

Some areas preserve abundant freshwater fish, mollusks, and plant fossils such as cycads, ferns, conifers, and gingkos. A locality in Princeton, New Jersey, for example, contained hundreds of coelocanth (known in the fossil record as ‘lobe-finned’ fish) and small bony fish. One of the more unusual vertebrate fossils found in this region is Icarosaurus siefkeri, a gliding, lizard-like reptile from the Triassic of North Bergen, New Jersey.

In general, however, the Northeast rift valley deposits have relatively few vertebrate bone fossils compared to footprints. Many of the small three-toed dinosaur footprints are known as Grallator, and were probably made by the late Triassic dinosaur known from the southwestern United States as Coelophysis. One place to see footprints is at the Walter Kidde Dinosaur Park (Riker Hill Fossil Site) in Roseland, New Jersey. The trackways protected in this park were discovered by high schoolers in the 1960s, and the site's discoverers later lobbied to conserve the trackways.

Part and counterpart of a frond of a fern (Clathropteris) from the Triassic of Newark, New Jersey. Photo of YPM PB 025799 by Yale Peabody Museum PB Staff, 2022 (GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

The coelacanth (lobe-finned fish) Diplurus from the Triassic to Jurassic of New Jersey. Specimen on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in Ohio, U.S.A. Photo by Tim Evanson (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

A gliding reptile (Icarosaurus siefkeri) from the Triassic Lockatong Formation, Newark Supergroup, New Jersey. Left: Cast of a fossil showing the elongated wings that formed the "wings" for gliding. Right: Artist's depiction of the living animal. Left photo by Patricia Holroyd, University of California Museum of Paleontology (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped); right drawing by Nobu Tamura (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped).

Pleistocene fossils

Cave fossils

Caves are an example in which the underlying geology, generally limestone, influences the Pleistocene record. Cave faunas are not terribly common in the Northeast, but are very important in some other areas of the country where caves are numerous. Important examples in the Northeast include a cave in Montgomery County, southeast Pennsylvania, which produced a large number of glacial age mammals that were described by Edward Drinker Cope, a scientist more famous for his dinosaur descriptions. Finds from the cave included a species of saber tooth cat, a small species of black bear, and the sloth Megalonyx.

Lake and pond fossils

Important and extensive freshwater and terrestrial remains occur in the innumerable pond sediments (not in the least lithified into rocks) left behind after retreat of the last glaciers. These ponds are well known from areas that were covered with ice and glacial sediment, especially kettles that formed along moraines and other ice-margin deposits. The ponds with large vertebrate remains are not randomly distributed, but can be clustered around well-known drainage systems, such as along the Hudson River Valley. Since such pond sediments are not surface outcrops, and since there is no foolproof technology for searching for bones under the sediment, most skeletons turn up during construction or pond alteration rather than through systematic searches for remains. Large vertebrate remains include mastodons, mammoths, giant beavers, peccaries, tapirs, foxes, bears, seals, deer, caribou, bison, and horses.

Nearly all glacial-age ponds contain a rich fossil record beyond vertebrates. In a typical pond, the first sediment to fill up the pond is fine-grained clays, followed later by organic-rich clays due to sedimentation of plant fragments as plant communities started to colonize the area after the glaciers had retreated. These clays often have plentiful late Pleistocene small freshwater mollusks, small pieces of fossil wood, and pollen, increasing as the plant community increased. The topmost sediment is often very late Pleistocene or Holocene peat, essentially pure plant matter made of innumerable tiny sticks and larger branches, leaves, cones, and other plant material. Since pollen shapes are indicative of the kinds of plants they come from, the pollen record can give a rather detailed account of how vegetation moved into the area as climate changed.

The Hyde Park mastodon is a mastodon that was preserved in a pond deposit in Hyde Park in the Hudson River Valley of New York. The Hyde park mastodon was discovered during a project to deepen a pond in the late 1990s. The skeleton was later excavated by staff of the Paleontological Research Institution, a project that required pumping all of the water out of the pond to find and retrieve the bones. In the end, almost the entire skeleton was recovered from the site, and the Hyde Park mastodon is now on display at the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York.

The Hyde Park mastodon (Paleontological Research Institution).

Mammoths also occurred in the region. The Mount Holly mammoth, a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), was discovered in Mount Holly, Rutland County, Vermont, during construction of a railroad in 1848; the remains consist of a molar, two tusks, and several other bones. Parts of the mammoth are on display in the Mount Holly Community Historical Museum, the Hood Museum of Art (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire), and the Museum of Comparative Zoology (Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts). The Mount Holly mammoth has recently been dated to about 12,800 years old, making it one of the youngest proboscidean (elephants and relatives) specimens known from New England. The young age of the specimen indicates that humans and woolly mammoths probably lived in New England at the same time near the end of the Pleistocene epoch.

Model of a woolly mammoth on display at the Royal Victoria Museum, British Columbia, Canada. Photo by Thomas Quine (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/

Hyde Park Mastodon (Museum of the Earth exhibits): https://www.museumoftheearth.org/exhibit/hyde-park-mastodon

Hyde Park Mastodon, 13,000+ 20 years later (PRI blog): https://www.priweb.org/blog-post/hyde-park-mastodon