Snapshot: Overview of the mineral resources of the Appalachian and Piedmont region of the northeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Metallic Resources; Non-Metallic Resources; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Mineral resources of the Northeastern US" by Jane E. Ansley, chapter 6 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Northeastern U.S. (published in 2000 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Andrielle Swaby, Elizabeth J. Hermsen, and Jonathan R. Hendricks. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 20, 2023.

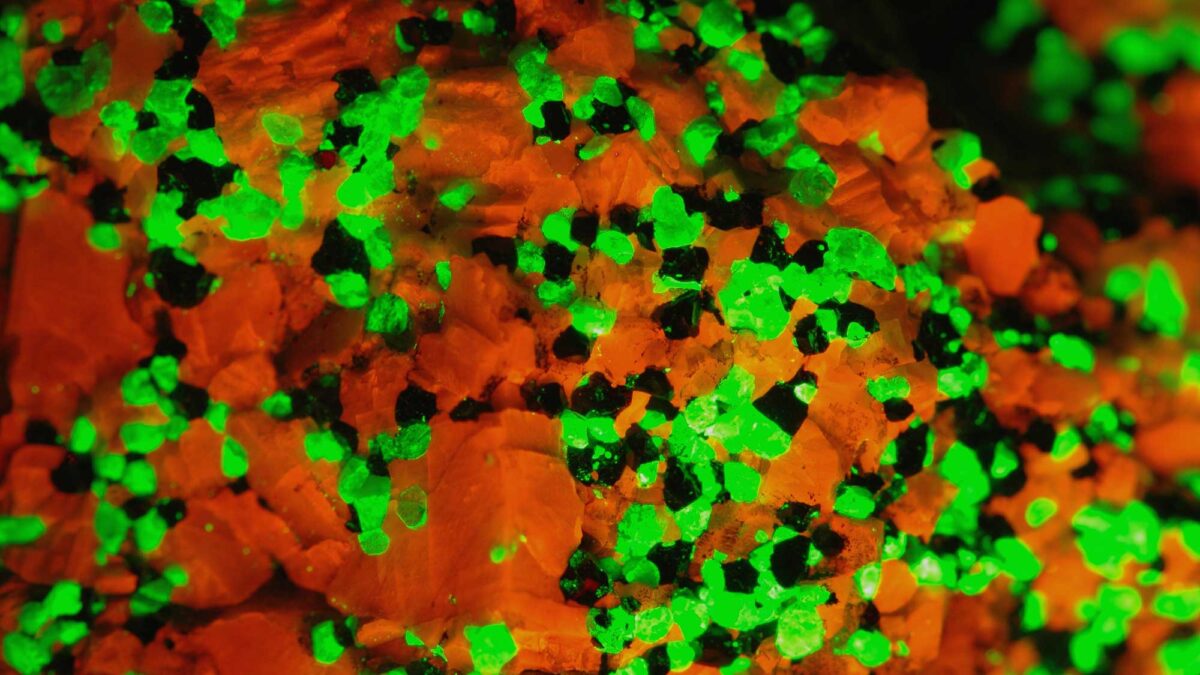

Image above: Sample of fluorescing zinciferous marble from Franklin, New Jersey shown under ultraviolet (UV) light. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

Overview

Though most of the mineral mining in the Appalachian/Piedmont stopped before the early 1900’s, there are still several principal mining localities in the region producing zinc, aluminum, titanium, talc and mica. Other important mineral resources of the Appalachian/Piedmont (though not currently mined) include: the kaolin of the Precambrian Grenville rocks; the Ultramafic Belt chrome and asbestos, formed from metamorphosed serpentinite when the Taconic volcanic islands collided with North America; and copper and magnetite deposits of the Triassic Rift Basin.

Metallic Resources

Grenville Rocks

The Precambrian Grenville rocks of the Appalachian/Piedmont region, located along the spine of the Appalachians, peek through the sedimentary rock cover such as in the Adirondacks of the Inland Basin region. Associated with the Grenville rocks in Pennsylvania and Maryland are significant deposits of zinc ore, in its most common form, sphalerite.

At Franklin Furnace and Sterling Hill, New Jersey, zinc ore in the Grenville rocks is also found, though the ore minerals are unusual. Over 340 different kinds of minerals have been found in the Franklin-Sterling HIll mining district, more than any other known place in the world. Franklin is known as the fluorescent mineral capital of the world because 80 of the 340 minerals fluoresce, or give off light, under ultraviolet (UV) light. The two large deposits of zinc, iron, and manganese contain the ore minerals franklinite (unique to the area), willemite, and zincite. The ore deposits at Franklin are found in Precambrian-aged Grenville marble.

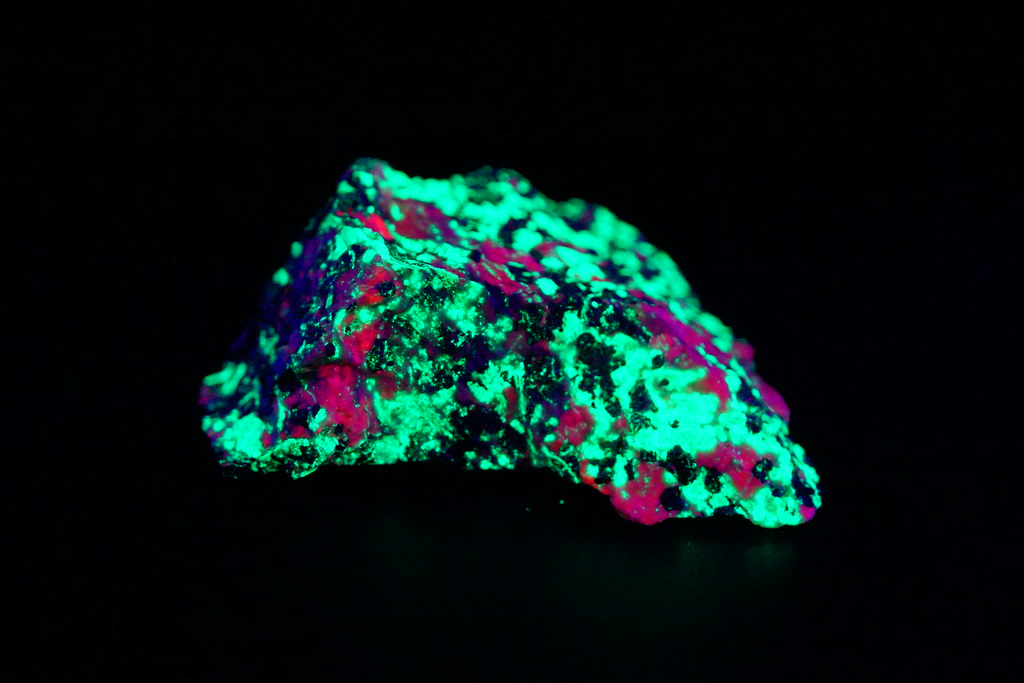

Sample of Willemite from the Franklin Mining District of Sussex County, New Jersey shown under regular light (compare with image of same specimen below). Photograph by "Tjflex2 (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Sample of Willemite from the Franklin Mining District of Sussex County, New Jersey shown under ultraviolet light (compare with image of same specimen above). Photograph by "Tjflex2 (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Serpentine rocks

The Ultramafic Belt that extends the length of the Appalachian/Piedmont region from Vermont to Maryland contains a variety of minerals unique to the serpentinite rock found in the belt. The serpentinite rock itself is unusual, produced from the alteration of peridotites by metamorphism. The peridotite, derived from magma from the upper mantle of the Earth, was originally part of the oceanic crust. However, as the North American tectonic plate and the Taconic volcanic islands gradually drew closer together, the intervening oceanic crust was being pushed beneath the North American plate. Some of the oceanic crust was scraped off and welded onto the side of North America as the rest of the oceanic crust was shoved down into the mantle. The peridotite of the oceanic crust was metamorphosed to form serpentinite, a rock rich in minerals not often found as part of the continental crust. A metallic mineral of note in the serpentinite rocks is chromite. The only ore of chromium, chromite was at one time mined in the Ultramafic Belt serpentinite rocks of Pennsylvania and Maryland. A dense, heavy mineral, chromite is one of the first minerals to crystallize and settle to the bottom of a cooling magma. It was thus concentrated in the serpentinite rocks in quantities sufficient to be profitably mined.

Chromitic serpentinite from the Soldiers Delight Ultramafite, Pennsylvania. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Rift basin rocks

The Newark and Gettysburg Triassic rift basins of the Appalachian/Piedmont region stretch through southeastern New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Formed during the rifting of Pangea away from North America, the rift basins contain alternating layers of igneous and sedimentary rocks. The resistant, ridge-forming igneous rocks, produced from lava flows (basalt) or igneous intrusions (diabase), contain mineral resources of economic importance to the region. In particular, magnetite is an important mineral resource in the Pennsylvania and New Jersey diabase rocks, concentrated and subsequently precipitated by hot flowing water through the rocks. Magnetite is one of the common ores of iron. Copper deposits are also associated with the basalt lavas of the rift basins.

Magnetite from the French Creek Mining District of Chester County, Pennsylvania. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Other rocks

Other important metallic minerals in the Appalachian/Piedmont region include nickel, molybdenum, titanium, manganese, cobalt, and graphite. In northern Delaware, titanium is an important mineral resource associated with the igneous rocks of the area, mined commercially for use as a paint pigment. In the Piedmont, gold is found in small quantities associated with quartz veins and fault zones in the metamorphic rocks of the region. Sillimanite, Delaware’s state mineral, is found in the Appalachian/Piedmont region of northern Delaware as large crystals produced from aluminum-rich rocks that were deeply buried and subjected to intense metamorphism. Though the mineral is not limited to Delaware, the unusually large crystals of sillimanite found there are rare elsewhere.

Non-Metallic Resources

The Grenville and Serpentine rocks of the Ultramafic Belt, and the Rift Basins of the Appalachian/Piedmont, host a plethora of non-metallic mineral resources in addition to the metallic minerals discussed above.

Grenville rocks

There is an abundance of non-metallic mineral resources in the billion-year-old Grenville rocks, including mica, feldspar and quartz. Mica, a common mineral in igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks, is mined in southern Pennsylvania in Adams County from the Precambrian Grenville rocks that form South Mountain. Kaolinite, a white clay formed from the weathering of feldspar, is mined in Vermont.

Serpentinite rocks

The Ultramafic Belt of serpentinite contains at least two important associated non-metallic minerals, which commonly form through the metamorphism of the magnesium-rich rocks: asbestos and talc. At one time, Vermont produced the most asbestos in the United States, though it is no longer mined there. Talc continues to be mined in Vermont today. An extremely soft mineral, talc can be scratched easily with your fingernail and has a soapy, greasy feel typical of very soft minerals.

Sample of Talc from Argonaut Quarry, Windsor County, Vermont. Photograph by Stephanie Clifford (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Rift Basin rocks

The Triassic Rift Basin of the Appalachian/Piedmont also has its share of non-metallic minerals. Basalt, formed as lava broke out of the crust and flowed across the surface of the basin, cooled quickly, trapping gas bubbles within the rock that left small cavities. Later, as water flowed through the rock, minerals were precipitated in the cavities, forming crystals such as the green mineral prehnite. Paterson and Bergen Hill, New Jersey are known for this mineral.

Sample of prehnite from Passaic County, New Jersey. Photograph by Rhiannon Boyle (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Gemstones

In addition to the non-metallic minerals discussed above, the Appalachian/Piedmont region produces several types of gemstones. The very common mineral feldspar has several relatively rare varieties found in Pennsylvania that are sold as the gemstones sunstone and moonstone. Amethyst, smoky quartz, agate, garnet and beryl are also found in the region. Beryl is common in granites and pegmatites and comes in a variety of colors.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life: Minerals (collection of 3D models on Sketchfab): https://skfb.ly/6WxTo

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals: https://earthathome.org/de/minerals/