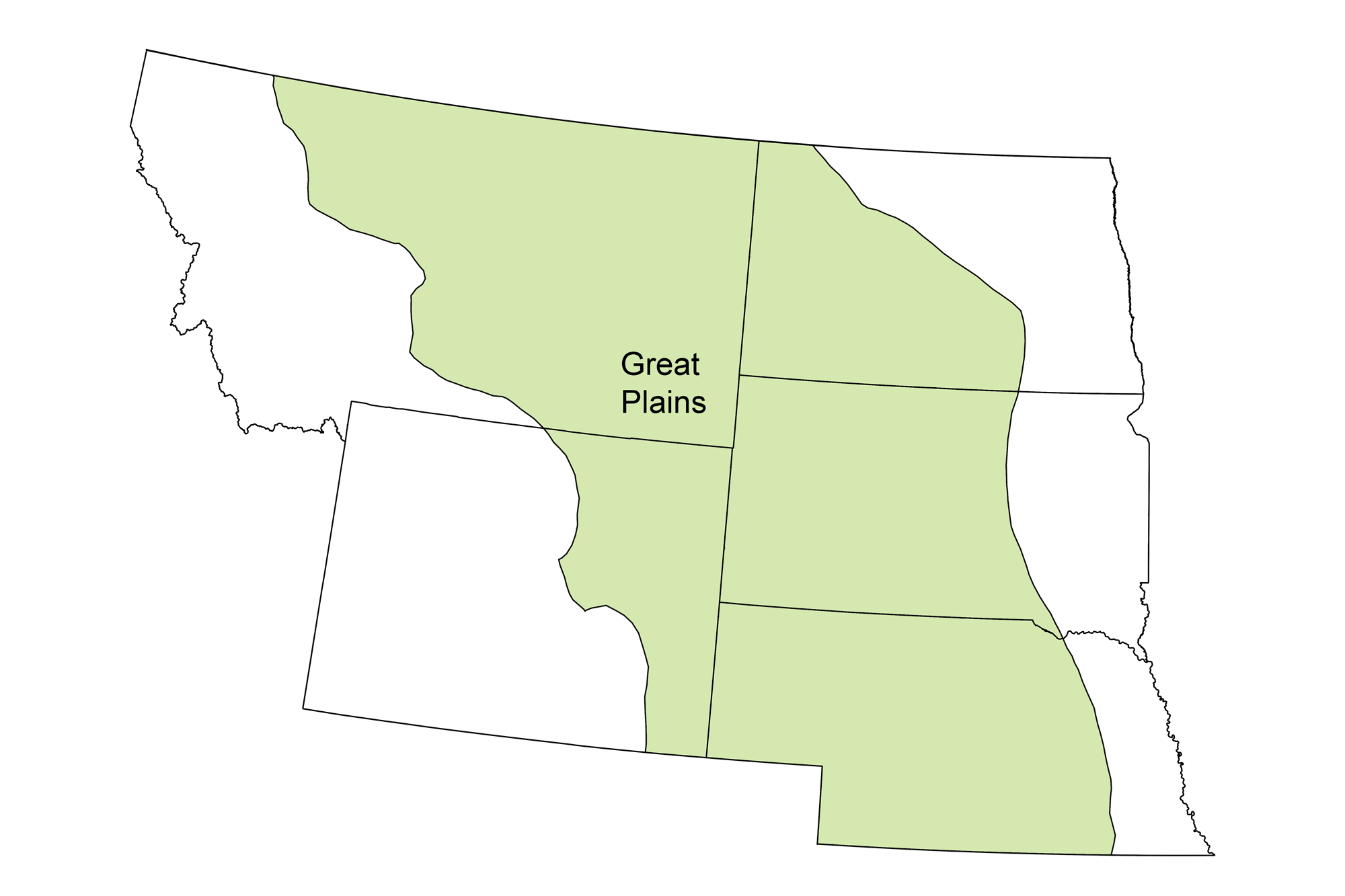

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Great Plains region of the northwest-central United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Mississippian Bear Gulch fauna; Cretaceous fossils; Cretaceous marine fossils; Cretaceous terrestrial fossils; Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation; Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation; Latest Cretaceous Hell Creek and Lance formations; Tyrannosaurus rex; Dinosaur mummies; Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction; Cenozoic fossils; Paleogene fossils; White River Group; Neogene fossils; Agate Fossil Beds; Quaternary fossils; Giant bison; The Columbian mammoth; Resources.

Credits: Much of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Northwest Central US" by Warren D. Allmon and Dana S. Friend, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northwest Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting, revisions, and additions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 17, 2023.

Image above: A fossil rhino (Menoceras) bone bed, Miocene Harrison Formation, Nebraska. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Paleozoic fossils

Paleozoic rocks occur at the surface in the Great Plains only because of tectonic forces that have uplifted the younger rocks and caused them to erode, exposing the older rocks beneath. The Black Hills of western South Dakota are a particularly striking example of this phenomenon. The center of the Black Hills consists of Precambrian igneous rocks, which are surrounded by a rim of Paleozoic sedimentary rocks.

The oldest sedimentary rock formation in the Black Hills is the Deadwood Formation, a layer of late Cambrian sandstone that outcrops around the town of Deadwood. The Deadwood Formation contains abundant marine fossils, including trilobites, brachiopods, trace fossils (burrows). Cambrian trilobites and brachiopods are also known from rocks in central Montana.

The Ordovician Whitewood and Mississippian Pahasapa limestones overlie the Deadwood, forming concentric rings farther from the core of the Black Hills. These younger layers also contain abundant and diverse marine fossils, including corals, snails, and cephalopods.

Fossil-bearing early Paleozoic rocks of South Dakota. Left: Shelly fossils in the Cambrian Deadwood Formation. Right: Fossils in the Ordovician Whitewood Limestone. Photos by Alton Dooley (Updates from the Paleontology Lab, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license, images cropped).

Brachiopods preserved in the Mississippian Pahasapa Limestone, Wind Cave National Park, Custer County, South Dakota. Source: NPS photo (public domain).

A coral preserved in the Mississippian Pahasapa Limestone, Wind Cave National Park, Custer County, South Dakota. Source: NPS photo (public domain).

Mississippian Bear Gulch fauna

Mississippian-aged rocks in this part of the Great Plains are correlated—determined to be the same age—mostly by using tiny fossils called conodonts as index fossils. Mississippian-aged rocks in North Dakota include the Bakken Shale, which is an important oil-producing layer. The oil comes from the altered remains of organisms that lived in a shallow sea.

The Mississippian Bear Gulch Beds of central Montana reveal a rare preservational “window” into the marine life of this time. The Bear Gulch Beds consist of layers of fine-grained limestone. These rocks are exposed at the surface only because of the Potter Creek Dome, an uplifted outcrop located about 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) northeast of the Big Snowy Mountains in Fergus County, Montana. Bear Gulch preserves one of the most diverse fossil fish assemblages in the world, as well as fossils of many beautifully preserved soft-bodied organisms, including arthropods, snails (gastropods), sea stars, nautiloid cephalopods, brachiopods, sponges, worms, and algae.

A mantis shrimp (Tyrannophontes acanthocercus) from the Mississippian Bear Gulch fauna of Montana. Photo by Oilshale (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

A cephalopod (Reticycloceras) from the Mississippian Bear Gulch fauna of Montana. Photo by Oilshale (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

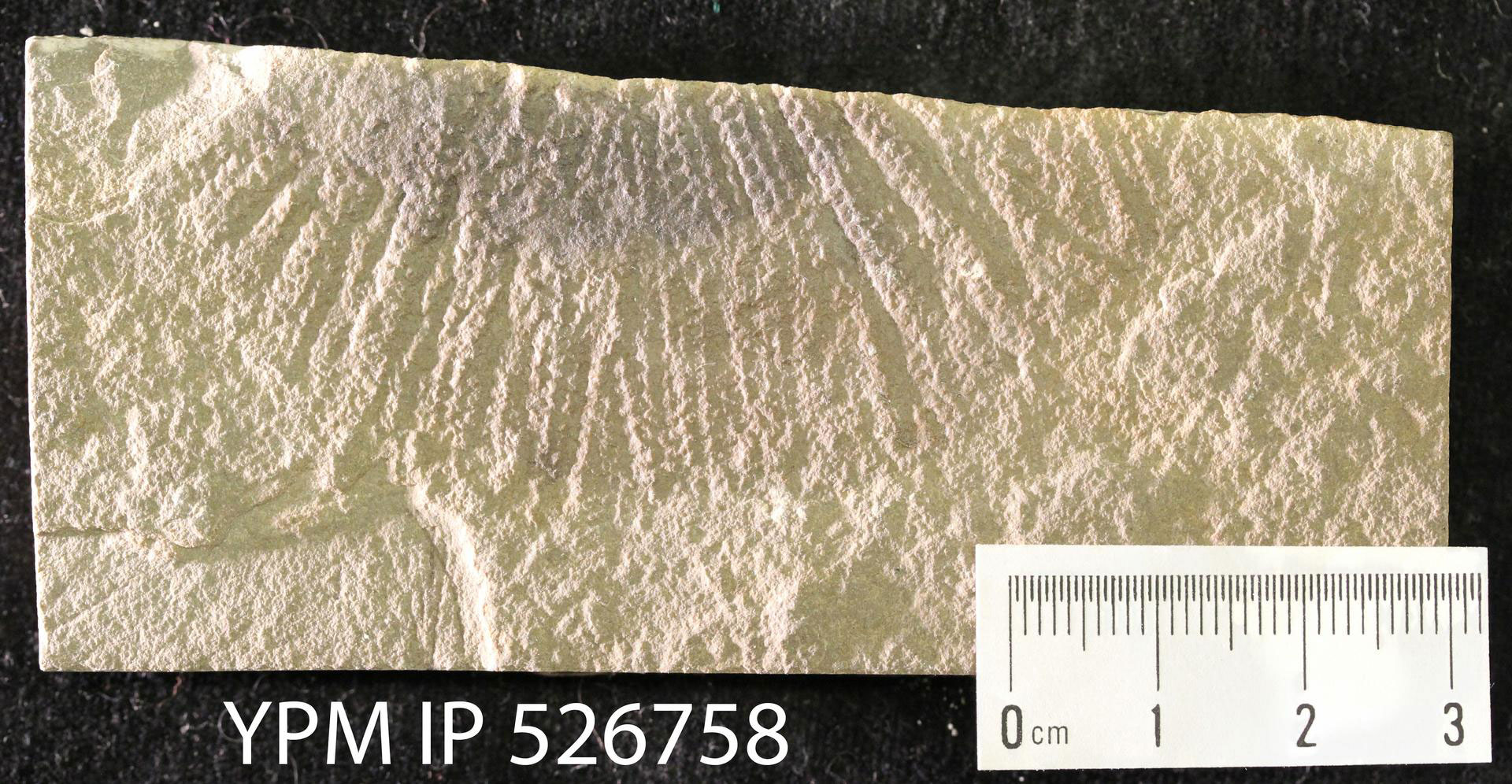

An echinoderm (Lepidasterella montanensis), Mississippian Bear Gulch fauna of Montana. Photo of YPM IP 526759 by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

A fish (Falcatus falcatus) from the Carboniferous of Montana. Specimen on display at Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Kalsruhe, Germany. Photo by H. Zell (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped).

Cretaceous fossils

Cretaceous marine fossils

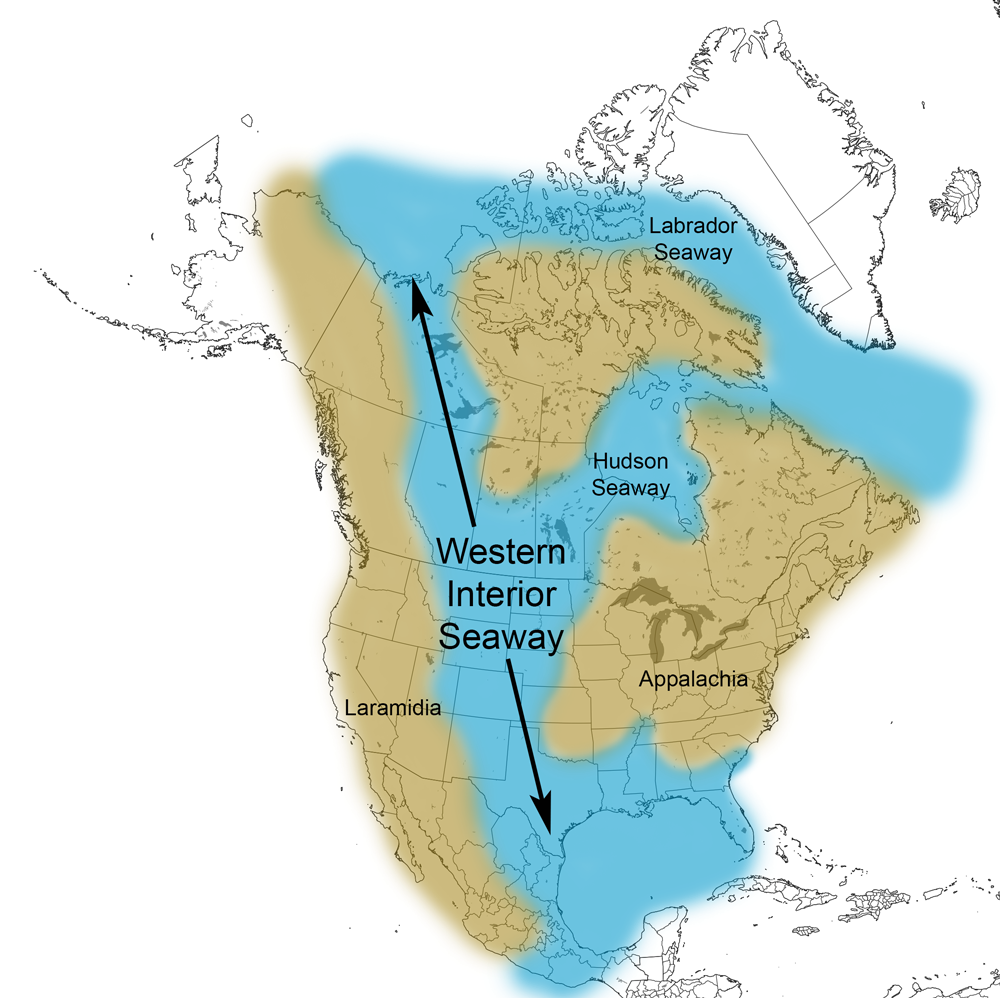

In the Cretaceous, global sea levels rose, spreading shallow epicontinental seas over much of the continent. The Western Interior Seaway stretched across the center of North America from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean, and from the foot of the still-forming Rocky Mountains to as far east as Iowa. It covered most of the Dakotas and Nebraska, as well as eastern Montana, east-central Wyoming, and eastern Colorado. An abundance of aquatic life thrived there for tens of millions of years, and most of the bedrock in those states is of Cretaceous age.

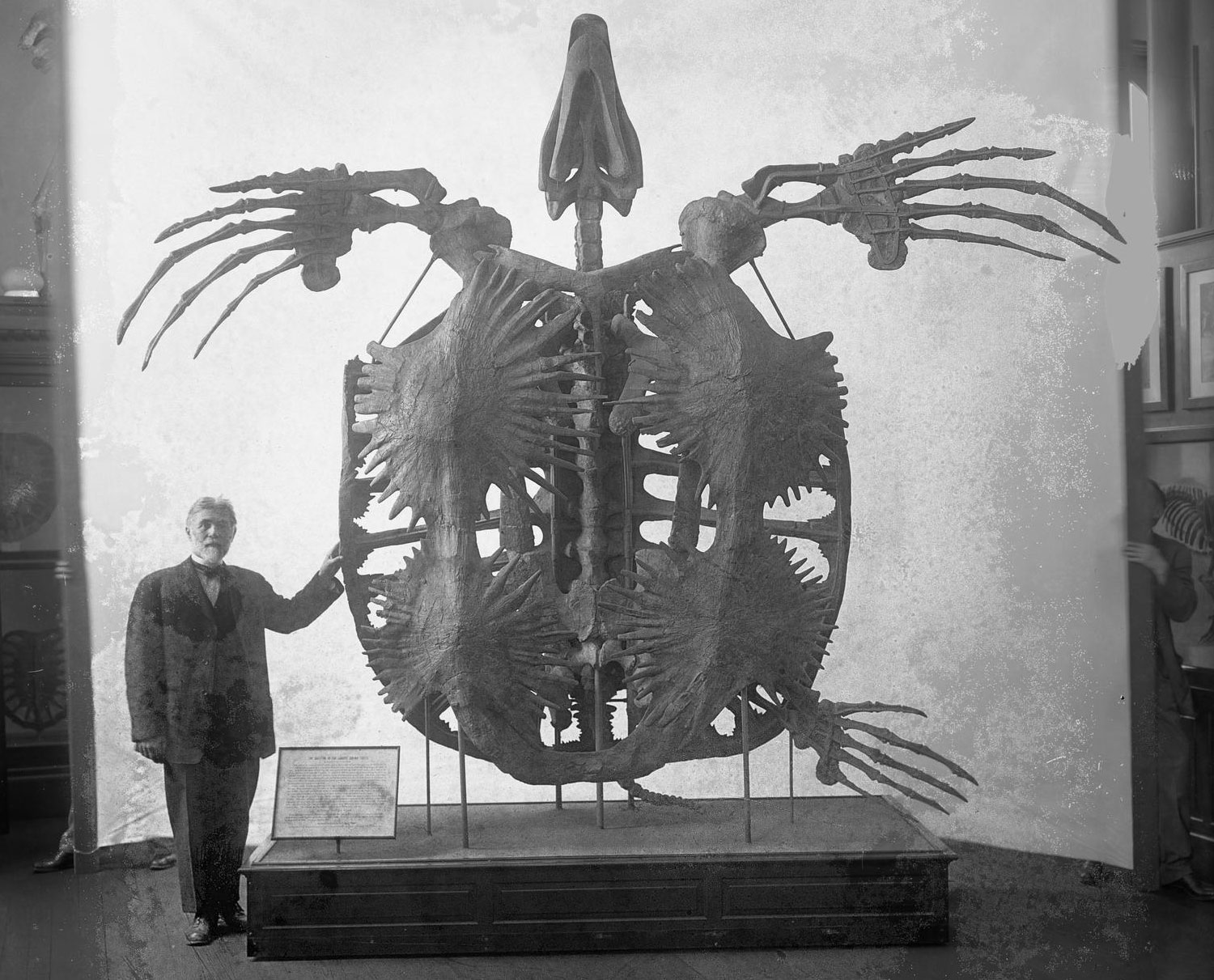

Over the course of the Cretaceous, the shores of this seaway swept back and forth, resulting in the deposition of alternating layers of marine and terrestrial rocks. Deeper waters toward the center of the Seaway led to the deposition of chalk, a carbonate rock made up primarily of the shells of microscopic marine algae called coccolithophores. The Western Interior Seaway was also home to huge marine reptiles—including plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, and turtles, which are frequently found as fossils in Cretaceous rocks in Nebraska and the Dakotas—as well as bony fish, sharks, and sea birds.

Extent of the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous Period. Image from Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Skulls of fish from the Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Niobrara County, Wyoming. Left: Cimolichthys (USNM V 18318). Right: Pachyrhizodus (USNM V 18321). Left photo by Michael Brett Surmann, right photo by Bruce Martin (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

A mosasaur (Platycarpus ictericus) from the Cretaceous of South Dakota. Left: Full specimen. Right: Detail of skull. Specimen on display in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. Photos of RGM.401860 by Naturalis Biodiversity Center (on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

A giant seaturtle (Archelon ischyros) from the Cretaceous Pierre Shale of South Dakota. Photo of YPM VP 003000 by Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Marine invertebrates in these Mesozoic seas were very different from those that had filled the seas of the Paleozoic. Rugose and tabulate corals were replaced by scleractinians (modern corals).

Brachiopods declined dramatically in abundance and diversity at the end of the Paleozoic, their ecological niches being filled in many cases by bivalves, or mollusks with shells made up of two valves (parts) connected at a hinge. Examples of modern bivalves include clams, mussels, and oysters. Inoceramids, relatives of living oysters, were diverse and abundant during the Cretaceous. Inoceramids lived on flat parts of the sea floor. The largest species of inoceramid could reach diameters of up to 1.5 meters (5 feet)!

False ark shell (Cucullaea nebrascensis, a type of clam), Late Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation, Ziebach County, South Dakota. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 24663 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

An inoceramid bivalve (Inoceramus sagensis), Late Cretaceous Pierre Shale, South Dakota. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 31434 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

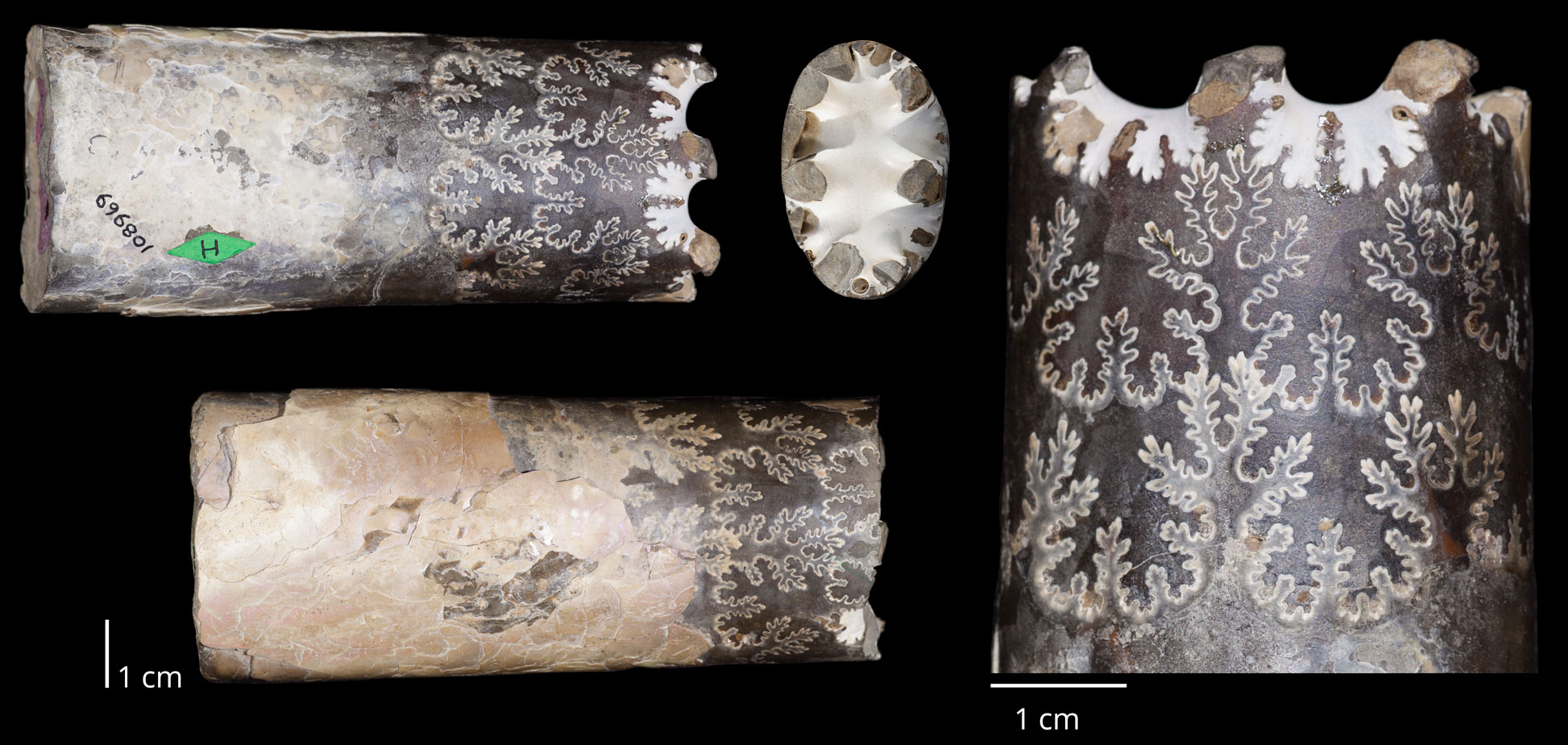

Ammonoids also became diverse and abundant and are especially common fossils in Cretaceous rocks of the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Montana. The late Cretaceous Pierre Shale, which is exposed widely across this area, is especially famous for its beautifully preserved ammonoids. The slight younger Fox Hills Formation yields equally impressive specimens.

Most ammonoids are coiled flat, in a single plane. One fascinating aspect of ammonoid evolution, however, was the appearance of shells with bizarre shapes, called heteromorphs (“different shape”). These unique ammonoids were especially prevalent in the Cretaceous period. The shells of heteromorphs were uncoiled or three-dimensionally (helically) coiled. Since there are no similar life forms today to which to compare them, it has been difficult to figure out how they lived—most current paleontological thinking suggests heteromorphs floated or swam.

An ammonoid (Discoscaphites gulosus), Late Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation, Dewey County, South Dakota. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 52828 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

An ammonoid (Discoscaphites gulosus), Late Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation, Dewey County, South Dakota. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 23689 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

A heteromorph ammonoid (Emperoceras beecheri), Late Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Custer County, South Dakota. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 52828 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

A heteromorph ammonoid (Didymoceras stevensoni), Late Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Carter County, Montana. Photo of USNM PAL 430976 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

A baculite, or straight-shelled ammonoid (Baculites eliasi), Late Cretaceous Bearpaw Shale, Montana. Photo of Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History USNM 108969 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

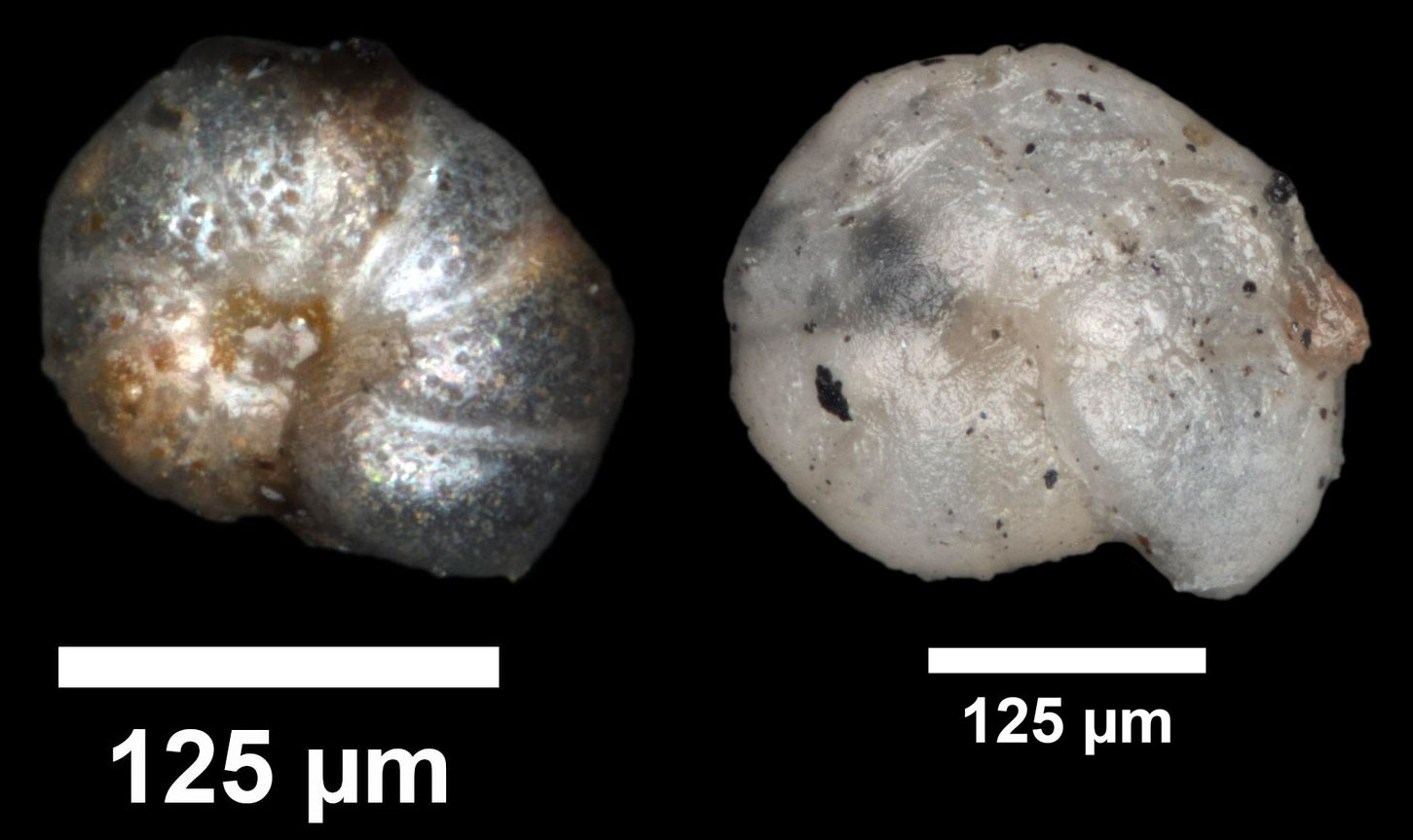

Abundant tiny fossils called foraminifera are found throughout Cretaceous sediments of the Western Interior Seaway. Foraminifera, or “forams,” as they are frequently called, are single-celled organisms (protists) with shells made of calcium carbonate. They live in the ocean in huge numbers, both at the bottom and floating in the water column and are extremely important as index fossils and paleoenvironmental indicators.

Foraminifera from the Late Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Corson County, South Dakota. Left: Anomalinoides minuta (YPM IP 022932). Right: Pullenia dakotensis (YPM IP 022933). Photos by Daniel J. Drew, 2018 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication). Note: 125 μm is 0.125 millimeters (0.005 inches).

Cretaceous terrestrial fossils

Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation

Fossil Cycad National Monument is a national monument that no longer exists. The monument was established in 1922 to protect an unusual concentration of Early Cretaceous fossil cycadeoids (an extinct group of Mesozoic plants that resemble modern cycads) preserved in the Lakota Formation near Minnekahta in southwestern South Dakota. Cycadeoids were plants that had pinnately compound leaves (leaves with a central axis and lateral pinnae or leaflets) and thick stems covered with leaf bases; they produced cones and seeds, but no flowers. The fossil stems, which were once abundant in the Minnekahta region, resemble and are sometimes mistaken for fossil beehives.

Unfortunately, most of the fossil cycadeoids around Minnekahta were collected by fossil dealers and scientists; in fact, most specimens may have been removed before Fossil Cycad National Monument was created. The monument was dissolved in 1957. The Lakota Formation also yields vertebrate fossils, including a few species of dinosaurs.

Cycadeoids. Left: A fossil cycadeoid (Cycadeoidea dacotensis) trunk, Early Cretaceous, South Dakota. Specimen on display at the National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C. Right: Model of a cycadeoid on display at the Field Museum, Chicago, Illinois. The structures that look like flowers are cones (cycadeoids are gymnosperms, not flowering plants). Left photo by Daderot (Wikimedia Commons, public domain). Right photo by E.J. Hermsen.

A group of cycadeoid (Cycadeoidea marshiana) trunks, Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation, Fall River County, South Dakota. Photo of YPM PB 151458 by Shusheng Hu, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (public domain).

Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation

In the late 1970s and 1980s, nests of dinosaur eggs—some containing embryos—were discovered in rocks of Montana’s Two Medicine Formation. Adult skeletons of the same dinosaur were found as well. The dinosaur was named Maiasaura, meaning “good mother lizard.” Maiasaura was a medium-sized hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) about 8 meters (26 feet) long. It was bipedal and plant-eating. Maiasaura was the first dinosaur ever found associated with nests of babies, and its embryos were the first dinosaur embryos ever found.

One of the sites where these fossils were found was named Egg Mountain; it is located west of Choteau in Teton County, Montana. The fossils showed that Maiasaura made a shallow nest in the ground about 2 meters (6.5 feet) in diameter, in which it laid clutches of 30 to 40 eggs. Because different nests had different-sized babies, paleontologists suggested that the babies were living in the nests when they died and were being cared for by their parents. Maiasaura has only been found in Montana and is the Montana state fossil.

Other dinosaurs found in the Two Medicine Formation include the herbivores like ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs), Gryposaurus (a hadrosaur), Orodromeus, and Scolosaurus (an armored dinosaur). Predators include Daspletosaurus and Troodon; Troodon eggs have also been found.

A herd of Maiasaura peeblesorum including adults and juveniles. Illustration by Debivort (SERC, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license, image resized).

Juvenile Maiasaura. Left: Model of a nest with hatchlings. Display at the Natural History Museum (London). Right: Juvenile Maiasaura skeletons. Display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, Colorado. Photos by Jonathan R. Hendricks (Earth@Home).

Cast and reconstruction of an embryo of Maiasaura in an egg. Specimen on display at the Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman, Montana. Photo by Tim Evanson (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

A ceratopsian or horned dinosaur (Brachyceratops montanensis), Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, Glacier County, Montana). Photo of USNM V 7591_15 by James Di Loreto (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

Daspletosaurus from the Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, Glacier County, Montana. Specimen on display at the Museum of the Rockies (Bozeman, Montana). Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Eggs of Troodon formosus, Egg Mountain, Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, Montana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Latest Cretaceous Hell Creek and Lance formations

During the latest part of the Cretaceous period (67–66 million years ago), the area that is now southeastern Montana, northeastern Wyoming, and northwestern South Dakota was a broad floodplain to the east of the developing Rocky Mountains, leading into the shallow marine Western Interior Seaway. In the northwest-central region, latest Cretaceous environments are preserved in the Hell Creek Formation in Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. In Wyoming, the upper part of the Lance (or Lance Creek) Formation is the same age and yields similar fossils.

The sediments deposited in these transitional environments contain the remains of organisms that lived both on land and in the sea. The terrestrial layers, deposited by meandering rivers, contain abundant plant fossils. These plant fossils include numerous flowering plants, which greatly diversified during the Late Cretaceous. Terrestrial deposits also contain abundant fossils of land-dwelling animals that lived near the seaway, including insects, freshwater snails and clams, amphibians, turtles, pterosaurs (an extinct group of flying reptiles), birds, and small mammals.

The leaf of a tulip-poplar-like tree (Liriodendrites bradacii) from the latest Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation, Bowman County, North Dakota. Photo of YPM PB 006360 by Division of Palaeobotany, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

A crocodile (Borealosuchus sternbergii) from the latest Cretaceous Lance Formation, Niobrara County, Wyoming. Photo of USNM V 6533 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

Fossil mammals from the latest Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation. Left: Lower jaw of a marsupial (Didelphodon vorax), or pouched mammal, Butte County, South Dakota. Right: Tooth of a multituberculate (Stygimys), an extinct group of small mammals, McCone County, Montana. Left photo of USNM PAL 560296 and right photo of USNM PAL 336362 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

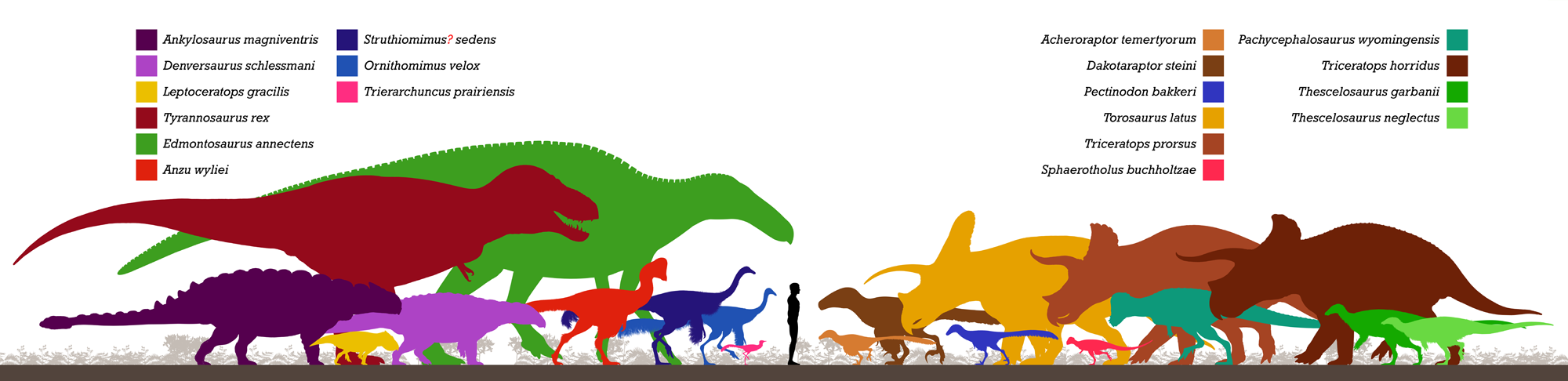

Dinosaur diversity

These formations are most famous for their multiple bone beds containing abundant dinosaurs, including Tyrannosaurus rex, the giant horned Triceratops, the “ostrich dinosaurs” Struthiomimus and Ornithomimus, the armored Ankylosaurus and dome-headed Pachycephalosaurus, and the large hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) Edmontosaurus and Anatotitan. They also preserve abundant fossil plants.

Dinosaurs of the Hell Creek Formation. Diagram by PaleoNeolitic (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Triceratops from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation, Niobrara County, Wyoming. Left: A Triceratops horridus named "Lane." Specimen on display at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas. Right: Triceratops prorsus. Left photo by Augustios Paleo (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized). Right photo of YPM VP 001822 by Vanessa R. Rhue, 2021 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis from the Cretaceous, Montana. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Edmontosaurs annectens from the Cretaceous, South Dakota. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Specimen on display in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. Photos of RGM.401870 by Naturalis Biodiversity Center (on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Tyrannosaurus rex

The first skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex was discovered in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by Barnum Brown in 1902. To date, dozens of additional T. rex specimens have been found (estimates of the total number vary) from as far north as Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada to as far south as New Mexico and maybe Texas in the U.S. Many T. rex specimens are held by museums in the United States and Canada, although a few are held by institutions overseas and some are owned by private collectors.

Tyrannosaurus rex has captivated people since the early twentieth century due to its enormous size and ferocious appearance. The largest specimen so far discovered, "Scotty" from Saskatchewan, Canada, was more than 12 meters (more than 40 feet) long and may have weighed more than 8,800 kilograms (nearly 20,000 pounds). Tyrannosaurus rex could stand more than 3.6 meters (about 12 feet tall) at the hips. Tyrannosaurus rex is generally thought to have been a predator, although some have argued that it was primarily a scavenger. (It should be noted, however, that many carnivores will both hunt and scavenge.)

Barnum Brown's 1902 Tyrannosaurus rex specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This is the holotype (main exemplar specimen) of T. rex. Photo by ScottRobertAnselmo (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Today, the most famous T. rex specimen from the Hell Creek Formation is undoubtedly "Sue." Sue was named for Sue Hendrickson, who discovered the dinosaur in 1990 on the Cheyenne River Reservation near Faith, South Dakota. After a court case to settle who owned the dinosaur, it was sold to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago for more than $8 million in 1997. Another T. rex from South Dakota, "Stan," was sold for more than $30 million in 2020. Stan is slated to go on display in Abu Dhabi.

The high prices commanded by these dinosaurs have spurred debate about the commodification of fossils. While some countries (like Canada) prohibit or strictly regulate the collection, sale, and export of fossils, laws governing the collection, ownership, and sale of fossils in the United States depend on who owns the land on which they are found.

Sue theTyrannosaurus rex on display at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by Evolutionnumber9 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Some other T. rex fossils on display in the U.S. include another of Barnum Brown's specimens at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and "The Nation's T. rex" (also known as "Wankel's T. rex") at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In the northwest-central region, "Montana's T. rex" (also called "Peck's Rex") is on display at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana. All of these specimens were found in Montana; the Nation's T. rex and Montana's T. rex were found on federal land and are thus publicly owned. Casts (high-quality reproductions) of T. rex specimens are also on display at museums around the country.

A specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex originally found by Barnum Brown in Montana, now on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Photo by Evolutionnumber9 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

The Nation'sT. rex on display at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Photo by Domenico Convertini (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Montana'sT. rex on display at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana. Photo by Tim Evanson (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Dinosaur mummies

Several dinosaur “mummies” have been found in Cretaceous beds in the northwest-central region. These exceptionally preserved fossils were formed when a dinosaur was buried suddenly, preserving impressions of skin and other traces of soft anatomy. Well-known Edmontosaurus mummies from the Lance Formation of Wyoming are on display at the American Museum of Natural History (New York City) and the Naturmuseum Senckenberg (Frankfurt, Germany). Another Edmontosaurus mummy called "Dakota" from the Hell Creek Formation is held by the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum in Bismarck, North Dakota. "Leonardo," a Brachylophosaurus mummy from the Judith River Formation of Montana (the Judith River Formation is similar in age to the Two Medicine Formation and older than the Hell Creek Formation) is on display in the Great Plains Dinosaur Center, Malta, Montana.

Mummy of Edmontosaurus annectens, Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation, eastern Wyoming. This specimen is on display in the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. Fig. 1a from Henry Fairfield Osborn (1912) Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History 1 (via Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Mummy of Brachylophosaurus canadensis, Late Cretaceous Judith River Formation, Phillips County, Montana. This specimen is on display in the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum and Field Station, Malta, Montana. Photo by the Children's Museum of Indianapolis (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

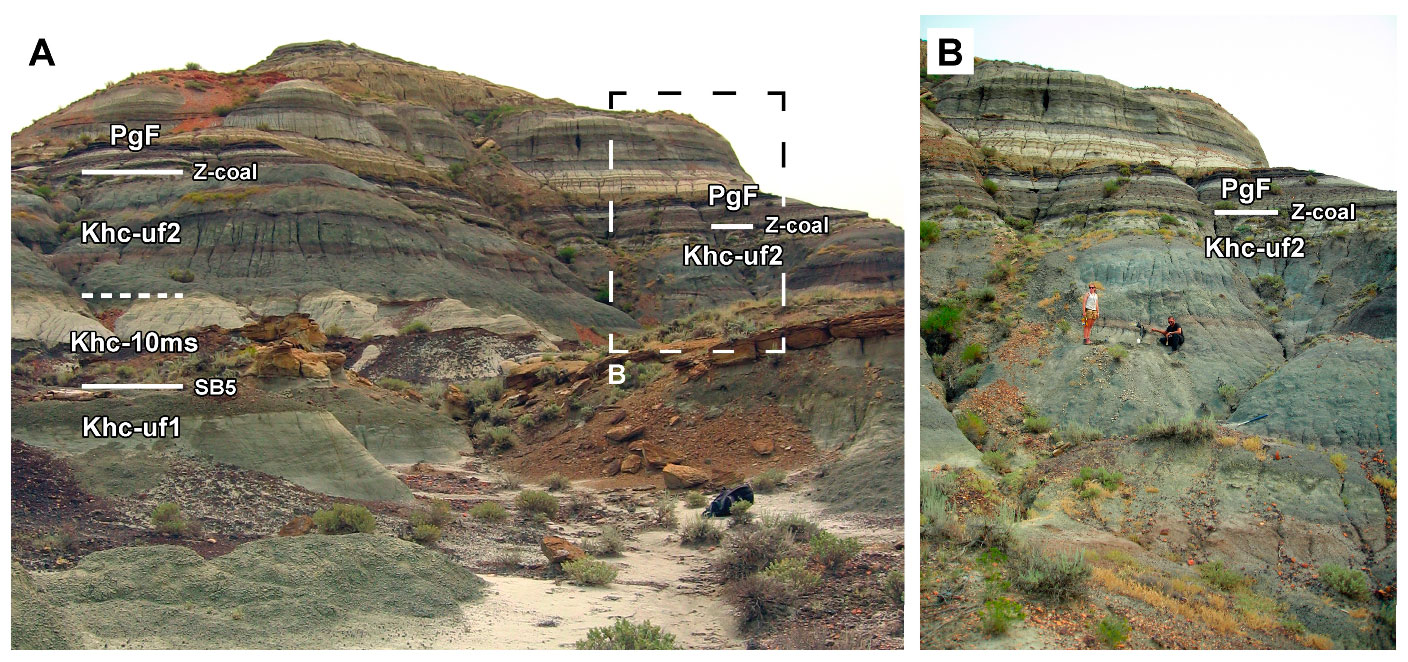

Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction

The boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods is found at the top of the Hell Creek and Lance formations, separating them from the overlying Paleogene Fort Union Formation. Detailed work in the late twentieth century showed that this boundary is now marked by a concentration of the element iridium. Most geologists think that the iridium came from a large comet or meteorite crashing into the Earth in the Yucatán region of Mexico. This impact was likely the primary cause of the mass extinction that marks the end of the Cretaceous period.

A butte near Jordan, Montana, that preserves the Z-coal marking the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary. Layers in the Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation are labeled Khc, whereas the overlying Paleogene Union Formation is labeled PgF. Source: Figure 21 from Fowler (2020) Geosciences 10(11) (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Cenozoic fossils

The early and mid-Cenozoic was a time of significant tectonic activity in the northwest-central States. The Western Interior Seaway disappeared by the end of the Paleocene, and most of the region became dry land. Nevertheless, extensive sedimentary deposits represent lakes, rivers, and floodplains. The uplift of mountain ranges to the west was a source of sediment that was transported and deposited by rivers in basins throughout the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain regions. Thick ash beds were also deposited in this area by periodic volcanic eruptions throughout the Cenozoic.

Cenozoic rocks preserve a fossilized view of ecosystems dramatically different from those of the Cretaceous. The dinosaurs disappeared, and mammals replaced them as the dominant large vertebrates on land. Fossil land mammals are particularly common in Cenozoic sediments of the Great Plains, beginning with the Paleocene and Eocene, and continuing through the Miocene. These fossils can be found in thick sequences of layered sedimentary rock, which accumulated in lakes and rivers that fed into the numerous basins across the region. The abundant fossil mammals preserved in these rocks form one of the most complete records of mammal evolution known anywhere in the world. Mammals are so numerous and diverse here that they are commonly used as index fossils. North American Land Mammal Ages (NALMAs) are used to describe the relative ages determined by fossil mammals.

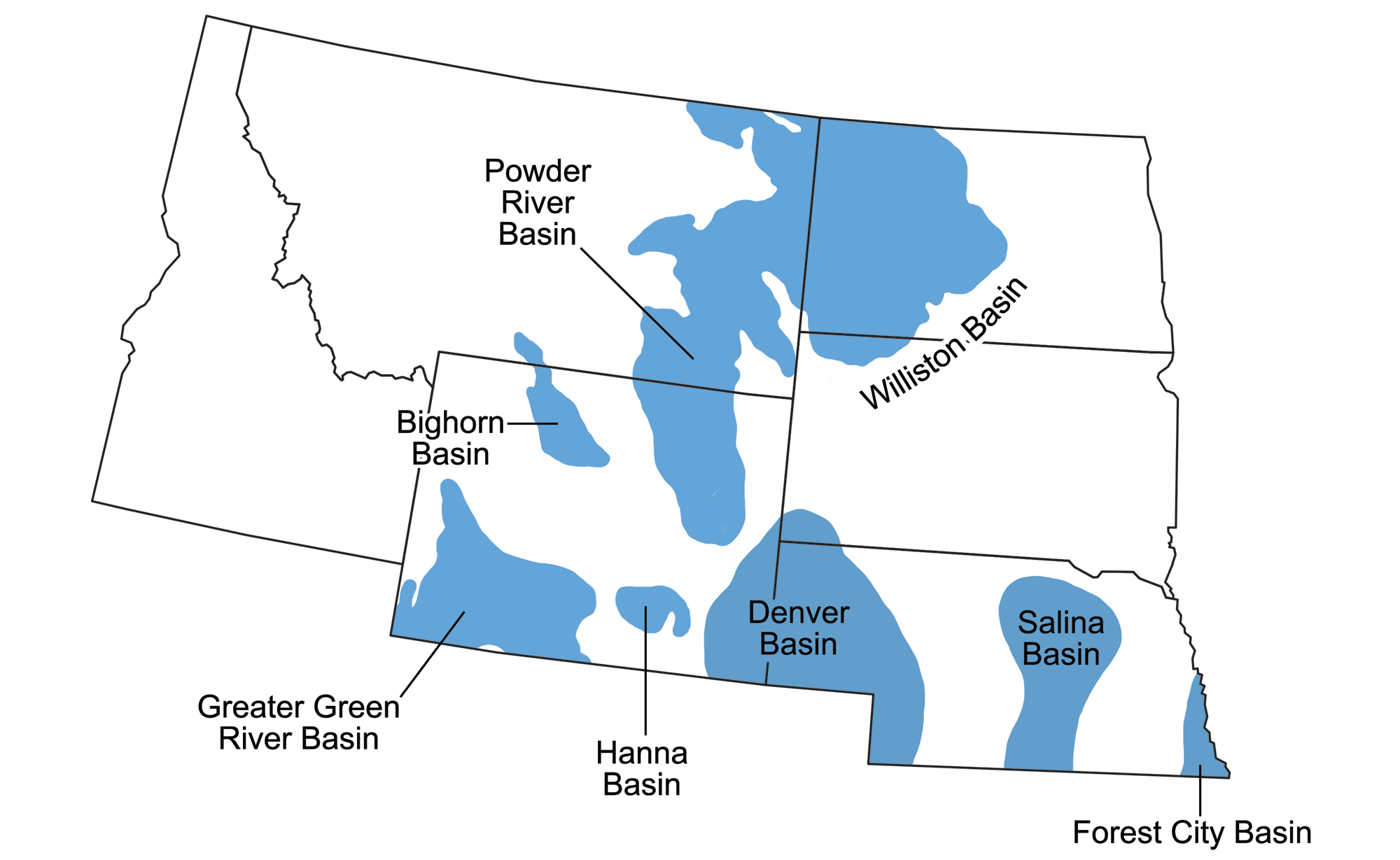

Sedimentary basins of the Northwest Central. Map by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northwest Central US.

Paleogene fossils

During this time, the environment was initially warm and humid, with widespread tropical and subtropical forests, but as global temperatures fell in the late Eocene and Oligocene, the climate of the Northwest Central became more arid, and grasslands replaced forests in many areas. The shrinking Western Interior Seaway is represented in the Dakotas by the Paleocene Cannonball Formation, which contains abundant and diverse mollusks, shark teeth, and occasional land plants.

Paleogene and early Neogene mammals from the northwest-central region include a great diversity of hoofed mammals, as well as carnivores and primates. Paleocene and Eocene mammals and plants are particularly common and diverse in the Williston Basin of the Dakotas and the Bridger and Uinta Basins of Wyoming and Utah.

Part of the lower jaw of a multituberculate, a type of small extinct mammal, from the Paleocene Fort Union Formation, Sweetgrass County, Montana. Photo of USNM V 9794 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

Branchlets and leaves of dawn redwood (Metasequoia occidentalis) from the Paleocene Golden Valley Formation, Oliver County, North Dakota. This genus of tree is native only to China today. Photo of YPM PB 028230 by Division of Paleobotany, Yale Peabody Museum (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Winged fruits of Cyclocarya brownii from the Paleocene Fort Union Formation, Morton County, North Dakota. This genus of tree is native only to China today. Photo of YPM PB 054382 by Division of Paleobotany, Yale Peabody Museum (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Petrified wood in the Paleocene Sentinel Butte Formation, Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota. Source: National Park Service (public domain).

White River Group

Oligocene mammals are best known from the White River Badlands, an area of western South Dakota with a deeply eroded landscape through which the White River flows. The rocks here are late Eocene to Oligocene in age (about 40–30 million years old) and were deposited by rivers moving through an environment much warmer and wetter than it is today. Fossil-bearing Oligocene rocks of the White River Group also extend beyond South Dakota into other states, including Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming.

These rocks contain some of the most abundant, diverse, and well-preserved Paleogene fossil mammals found anywhere in the world, such as extinct relatives of modern groups like camels and horses and groups that left no living descendants, including the pig-like entelodonts ("hell pigs") and the sheep-like oreodonts. Oreodonts were the most abundant mammals in the savannah-like environment. Nevertheless, some of the most common vertebrate fossils in Cenozoic sediments in Nebraska and the Dakotas are tortoises. Tortoises are a group of turtles that live on land; they have short, strong legs used for digging burrows.

Eocene tortoise shell from Nebraska. Specimen is from the Education Collection of the Paleontological Research Institution. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Fossil tortoises from the Oligocene White River Group (Brule Formation). Left: Gopherus praextans, Niobrara County, Wyoming. Right: Emys hemispherica, South Dakota. Photo of USNM V 16732 by Amanda Millhouse and photo of USNM V 16732 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

A beaded lizard (Glyptosaurus) from the Oligocene White River Group (Brule Formation), Converse County, Wyoming. Photo of USNM V 13869_5 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

A rodent (Ischyromys) from the Oligocene White River Group (Brule Formation), Niobrara County, Wyoming. Photo of USNM V 16828 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

A camel (Poebrotherium) from the Oligocene White River Group (Brule Formation), Sioux County, Nebraska. Photo of USNM V 15917 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

Fossil specimen of a Poebrotherium sp. camel skull exhibiting an endocast of the brain; specimen is from the Oligocene of Wyoming and is on exhibit at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York (PRI 49382). Model by Emily Hauf on Sketchfab.

Skull of an entelodont Archaeotherium), a "hell pig," from the Oligocene White River Group, South Dakota. Specimen on display at the Dakota Dinosaur Museum, Dickinson, North Dakota). Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

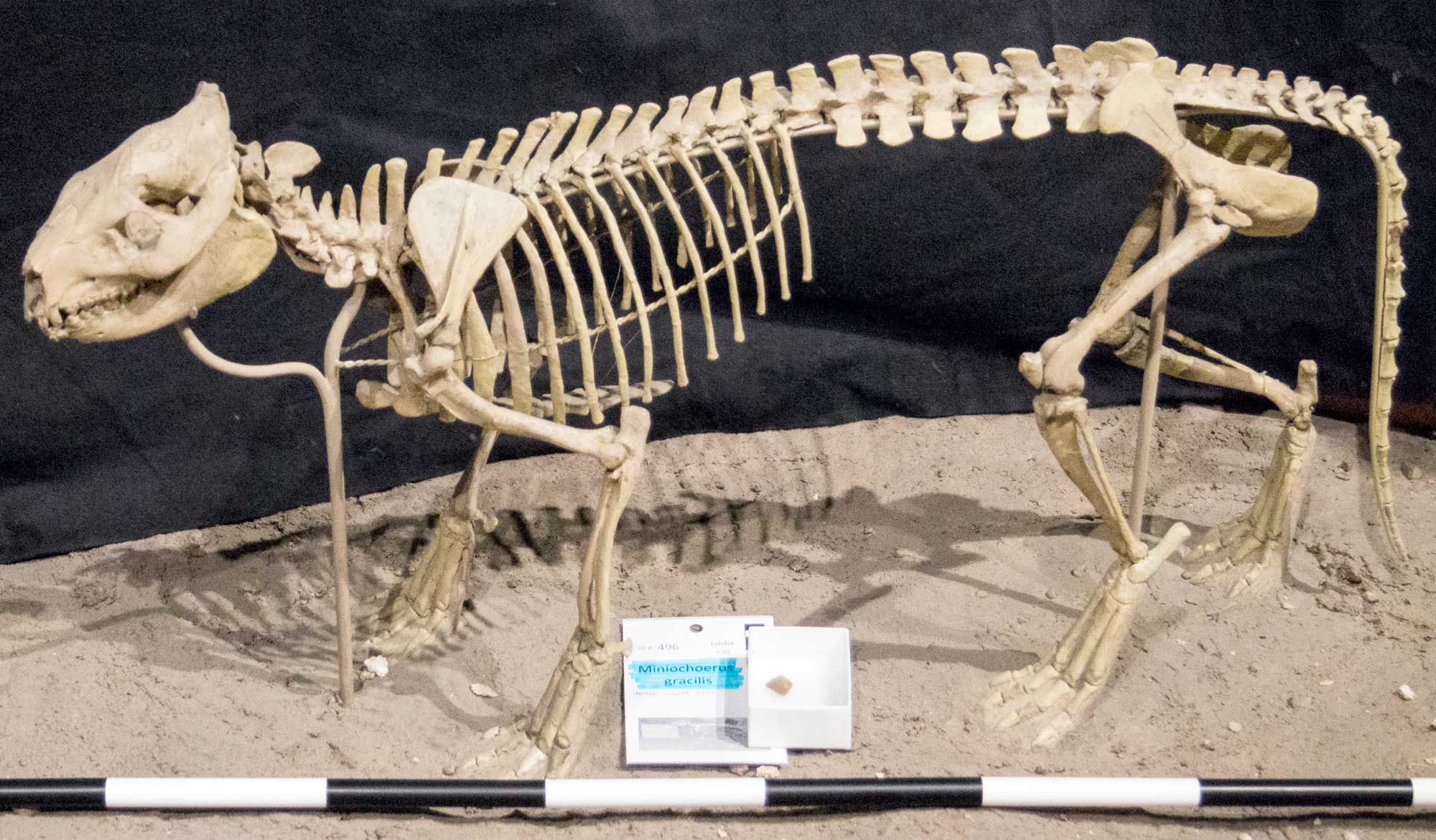

An oreodont (Miniochoerus gracilis) from the Oligocene White River Group (Brule Formation), Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska. Photo of USNM V 2455 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

Oreodont skull from the Paleogene of Nebraska. Specimen is part of the Paleontological Research Institution's education collection. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project.

Neogene fossils

Miocene mammals are abundantly preserved in a number of deposits, including the spectacular Agate Fossil Beds of western Nebraska, and the Ashfall Fossil Beds of northeastern Nebraska. Many of these fossil beds formed as a result of rapid burial in volcanic ash. The spectacular fossils exposed at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument and Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park reveal that during the early Miocene (about 21–19 million years ago), this area was a grassy savanna, similar to those in today’s East Africa.

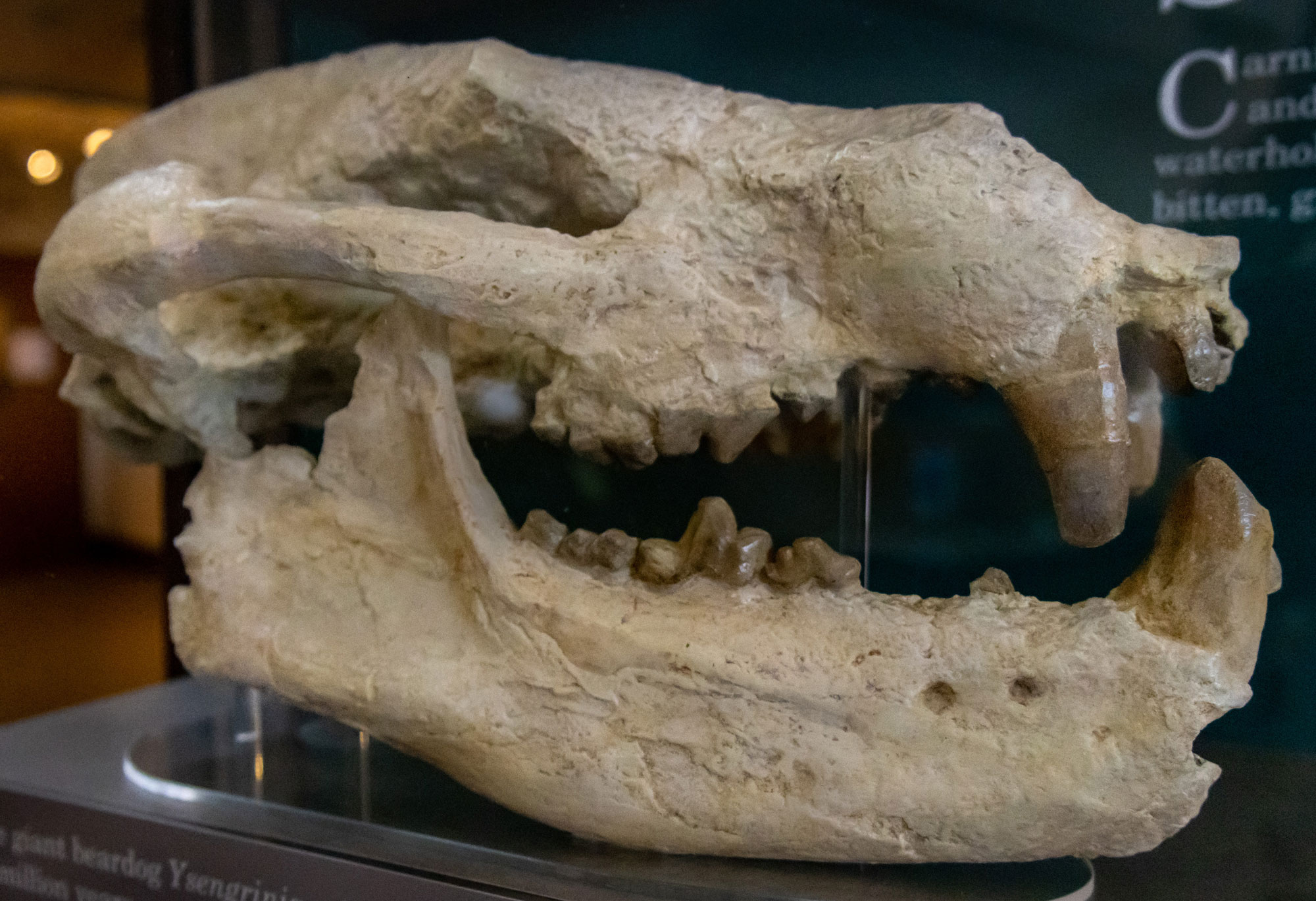

Miocene Nebraska was filled with diverse and abundant large mammals, including the small “gazelle-camel” Stenomylus, the short-legged rhinos Menoceras (the first rhino with horns) and Teleoceras, the carnivorous “beardogs” Daphoenodon and Ysengrinia, the fierce-looking giant entelodont (hell pig) Daeodon (formerly Dinohyus), the bizarre clawed herbivore Moropus, and the “land beaver” Paleocastor, which dug spectacular long spiral burrows known today as the trace fossil Daemonelix.

Skeletons of the North American rhino Teleoceras major preserved in a Miocene ash deposit, Ashfall Fossil Beds State Park, Antelope County, Nebraska. Photo by Ammodramus (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Agate Fossil Beds

Most of the fossils in the Agate Fossil Beds quarries were excavated from a bone bed that is as much as 60 centimeters (2 feet) thick in some areas. Particularly famous are accumulations of skeletons from the rhino Menoceras (see the image at the top of this page). These animals may have preferred to spend most of their time lying in shallow ponds or stream courses. When a multi-year drought occurred and the food supply disappeared, the Menoceras remained at the waterhole where they died. When water flowed again, the seasonal stream buried their bodies beneath layers of mixed sandy sediments and volcanic ash.

Fossil burrows, known as Daemonelix (“devil’s corkscrew”), of the extinct beaver Palaeocastor. This large burrow was discovered in the late 19th century at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. Photo of a vintage photo by James St. John (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Skull of a beardog (Ysengrinia), Miocene, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Sioux County, Nebraska. Photo by Jason Gray, NPS (National Park Service photo, public domain).

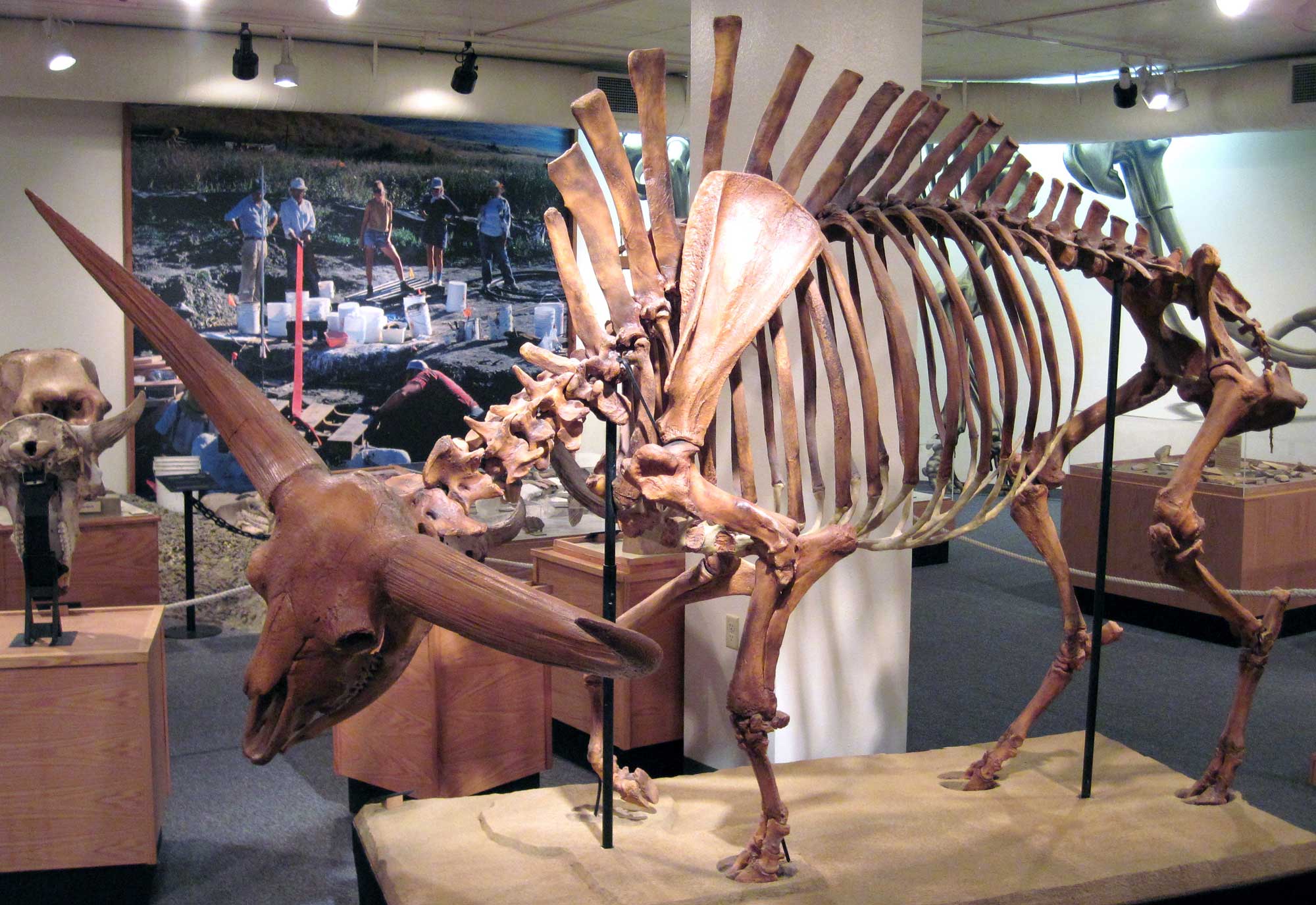

Recreated skeletons of two large entelodonts (hell pigs, Daeodon) and a beardog (Daphoenodon), Miocene, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Sioux County, Nebraska. The skeleton laying in the background is Moropus (see below). Photo by Jllm06 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Moropus elatus, a large perissodactyl (odd-toed ungulate mammal) from the Miocene Harrison Formation, Sioux County, Nebraska. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

A camel (Stenomylus hitchcocki) from the Miocene Harrison Formation, Sioux County, Nebraska. Photo of USNM V 16601 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

Quaternary fossils

The cooling temperatures that affected all of North America at the beginning of the Pleistocene epoch, around 2.5 million years ago, brought an influx of new mammals to the Great Plains. These included mammoths, rodents, bison, and musk oxen. Large mammals are not the only life forms preserved from the ice age. Freshwater and land mollusks are common to abundant in many soft sediment deposits across the Great Plains.

Giant bison

Bison first appear in North America in the late Pleistocene, around 200,000 years ago, having migrated from Asia across the Bering Land Bridge, a land bridge that existed between eastern Russia and Alaska when sea levels were lower during the Pleistocene. The oldest and largest of the several species that evolved here was the “giant bison,” Bison latifrons, which had horns measuring up to seven feet tip-to-tip, a shoulder height of 2.5 meters (8.2 feet), and may have weighed over 2000 kilograms (4400 pounds), up to twice the size of the modern American bison! The giant bison became extinct around 20,000–30,000 years ago, at the beginning of the last glacial maximum. Bones of this species, as well as those of other extinct species such as Bison antiquus, are common throughout the Great Plains, especially in Nebraska.

Bison latifrons, Pleistocene, North America (location not specified). Specimen on display in the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello, Idaho. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Bison antiquus, Pleistocene, Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska. Specimen on display in the Nebraska State Museum of Natural History, Lincoln, Nebraska. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

The Columbian mammoth

Mammoths were close cousins of modern elephants that lived across North America and Eurasia for several million years. At least three of different kinds of mammoths lived in North America until they mostly disappeared around 10,000 years ago (mammoths persisted on some isolated, far northern islands, going completely extinct only about 4000 years ago).

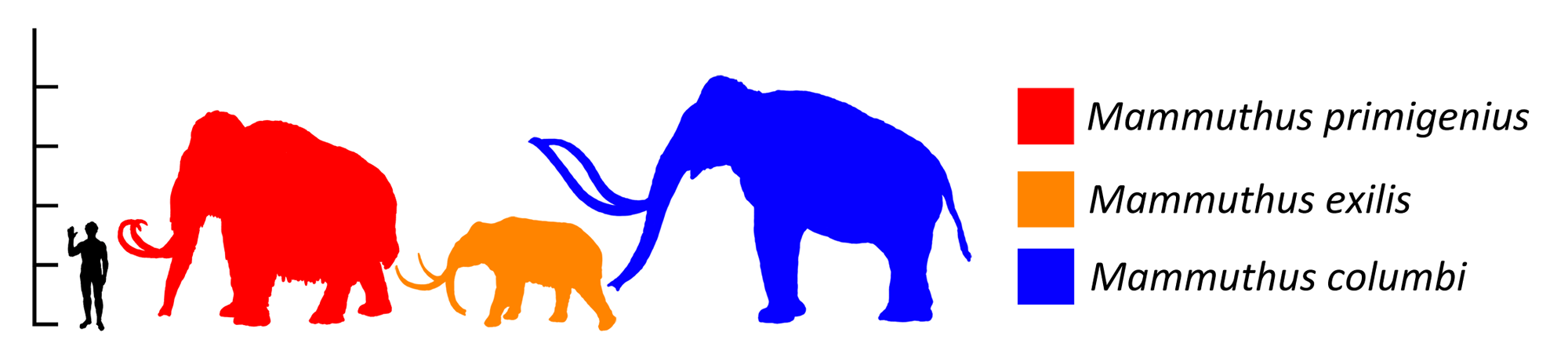

The most familiar kind of mammoth is the woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius, which lived in colder climates close to the glacial front. Woolly mammoths lived in both Eurasia and North America; in North America, their range extended from Alaska to the northeastern United States. The larger Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) ranged throughout most of the lower 48 U.S. states and into Mexico. The small pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis) was found only on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California.

Size comparison of the three types of mammoths found in the Pleistocene of North America. Diagram modified by a diagram by FunkMunk (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

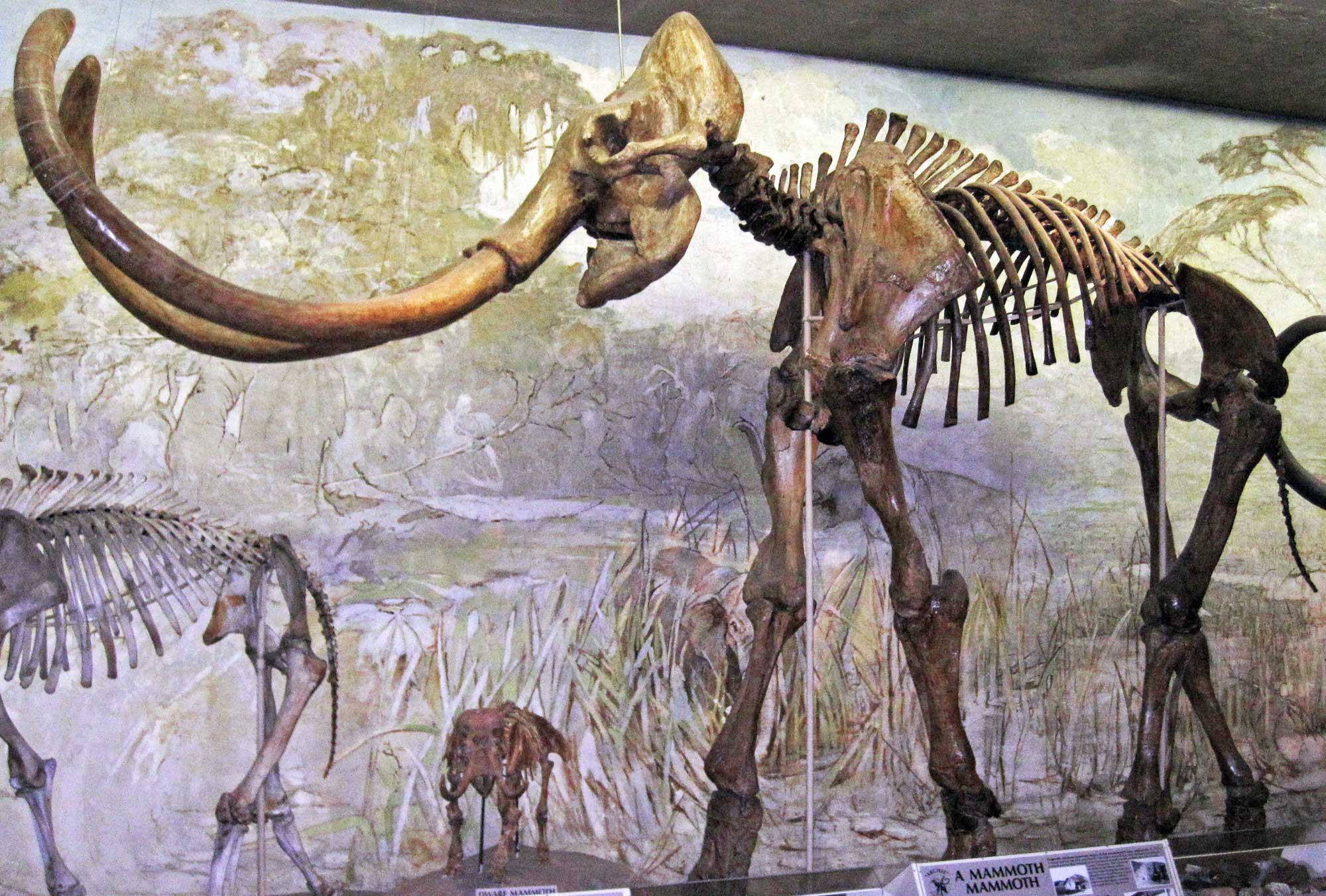

"Archie" the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), Pleistocene Lincoln County, Nebraska. Specimen on display at the Nebraska State Museum of Natural History. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

The Mammoth Site

At Mammoth Site in Hot Springs, South Dakota, the skeletons of at least 60 mammoths (mostly Columbian) are preserved together with the bones of many other ice age mammals, including camels, llamas, giant short-faced bears, wolves, coyotes, and prairie dogs. This extraordinary fossil assemblage formed around 26,000 years ago, when a cavern in the Minnelusa Limestone collapsed, creating a sinkhole into which the animals fell.

Exposed bone bed at the Mammoth Site, Pleistocene, Hot Springs, South Dakota. Photo by amanderson2 (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central United States: Fossils of the Great Plains (includes more about fossils from the Western Interior Seaway in western Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-gp/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern United States: Fossils of the Great Plains (includes more about fossils of the Great Plains in eastern Colorado and New Mexico): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/fossils-gp

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/