Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Great Plains region of the south-central United States.

Topics covered on this page: Mesozoic fossils; Triassic and Jurassic fossils; Cretaceous fossils of Kansas; Cretaceous fossils of Oklahoma and Texas; Cenozoic fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the South Central US" by Warren D. Allmon and Alex F. Wall, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the South Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 26, 2022.

Image above: Close up of a group of crinoids (Uintacrinus socialis) from the Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk, Kansas. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Mesozoic fossils

The Great Plains of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas are dominated by mid to late Mesozoic- and Cenozoic-aged rocks. Little of the bedrock in the region is older than 145 million years.

Triassic and Jurassic

The Triassic rocks of Texas crop out along the border between the Great Plains and Central Lowland regions. A variety of early dinosaurs are found in here, along with phytosaurs (extinct animals that look like crocodiles, although the two groups are not related) and synapsids (mammal-like reptiles). Triassic fossils from this region are covered on the Fossils of the Central Lowland and Interior Highlands page.

The Jurassic is not well represented in this region. However, the western panhandle of Oklahoma includes a small but important exposure of terrestrial shales and sandstones, which contain turtles, crocodiles, freshwater fish, and Oklahoma’s state fossil, the large allosaur Saurophaganax.

Postosuchus kirkpatricki, a Triassic archosaur first described from material found at the Post Quarry site, Garza County, Texas. Photo of a specimen on display at the Museum of Texas Tech University by Dallas Krentzel (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Saurophaganax maximus. Left: Mounted skeleton at the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. Image from "Friday phalanges: Megaraptor vs. Saurophaganax" by Matt Wedel (SV-Pow, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized). Right: Reconstruction of what Saurphaganax may have looked like in by Mario Lanzas (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Cretaceous

Cretaceous fossils of Kansas

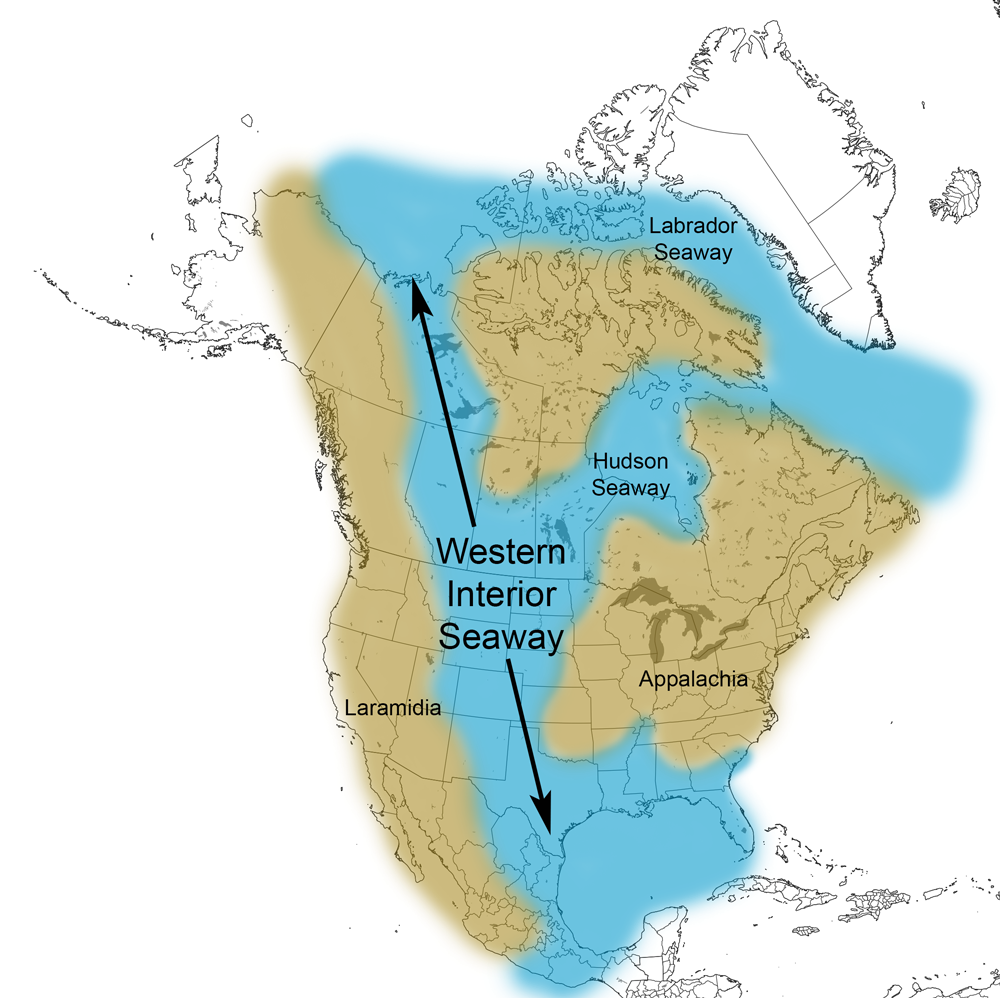

The Cretaceous rocks of Kansas contain abundant remains of late Mesozoic marine life, including some of the best fossils in the world from this time period. Fossils of marine invertebrates indicate that a warm, shallow sea covered the western part of the state, while terrestrial plant fossils and coal seams in central Kansas represent near-shore wetlands. These wetlands mark the shore of the great Western Interior Seaway, which divided North America into two landmasses as it extended from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. The flat floor of this inland sea provided the basis for the modern topography of the Interior Plains.

Extent of the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous Period. Image from Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

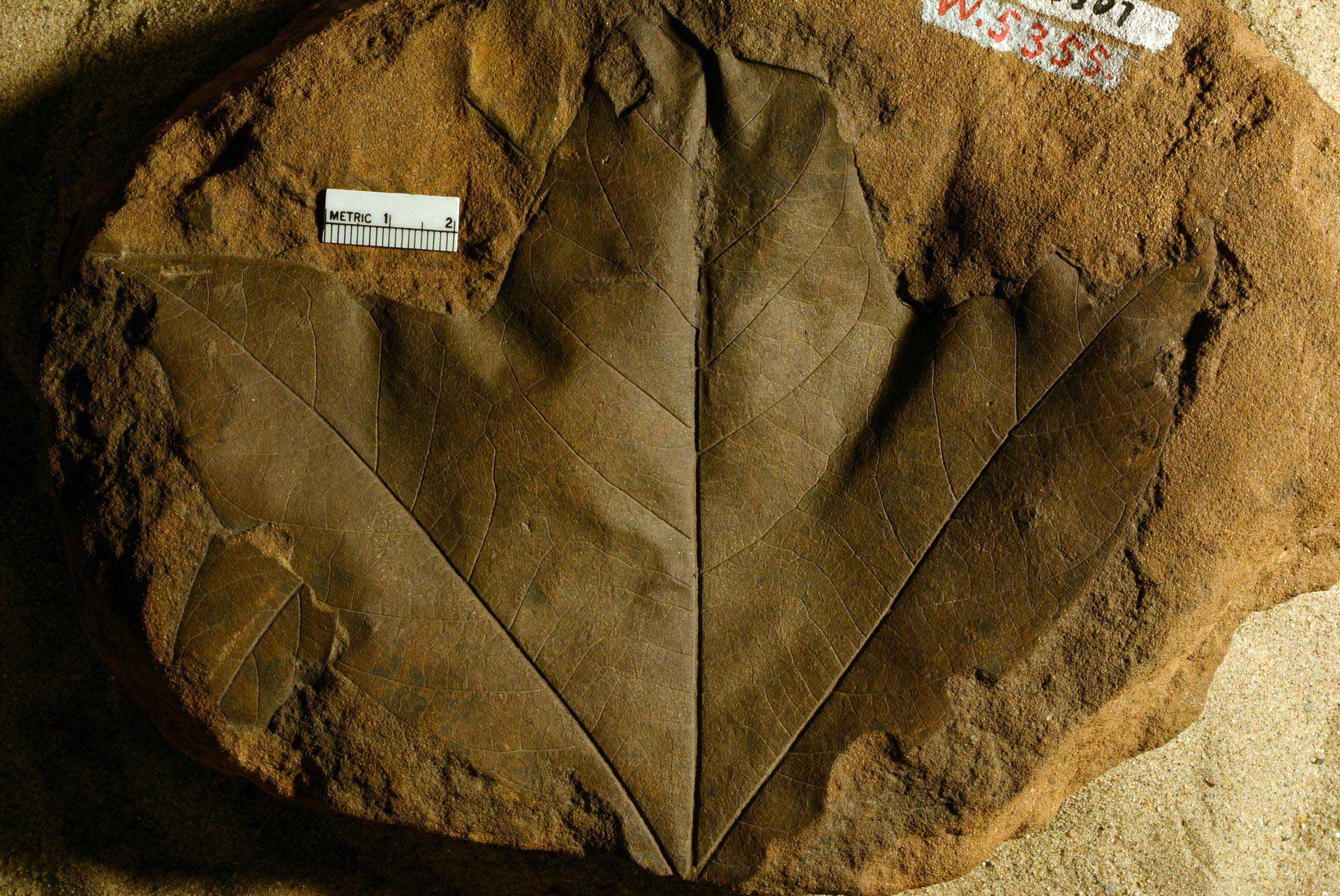

Leaf of a sycamore tree (Platanus), Early Cretaceous, Dakota Sandstone, Saline County, Kansas. Photo of YPM PB 040687 by Tsveta Ivanova, 2020 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

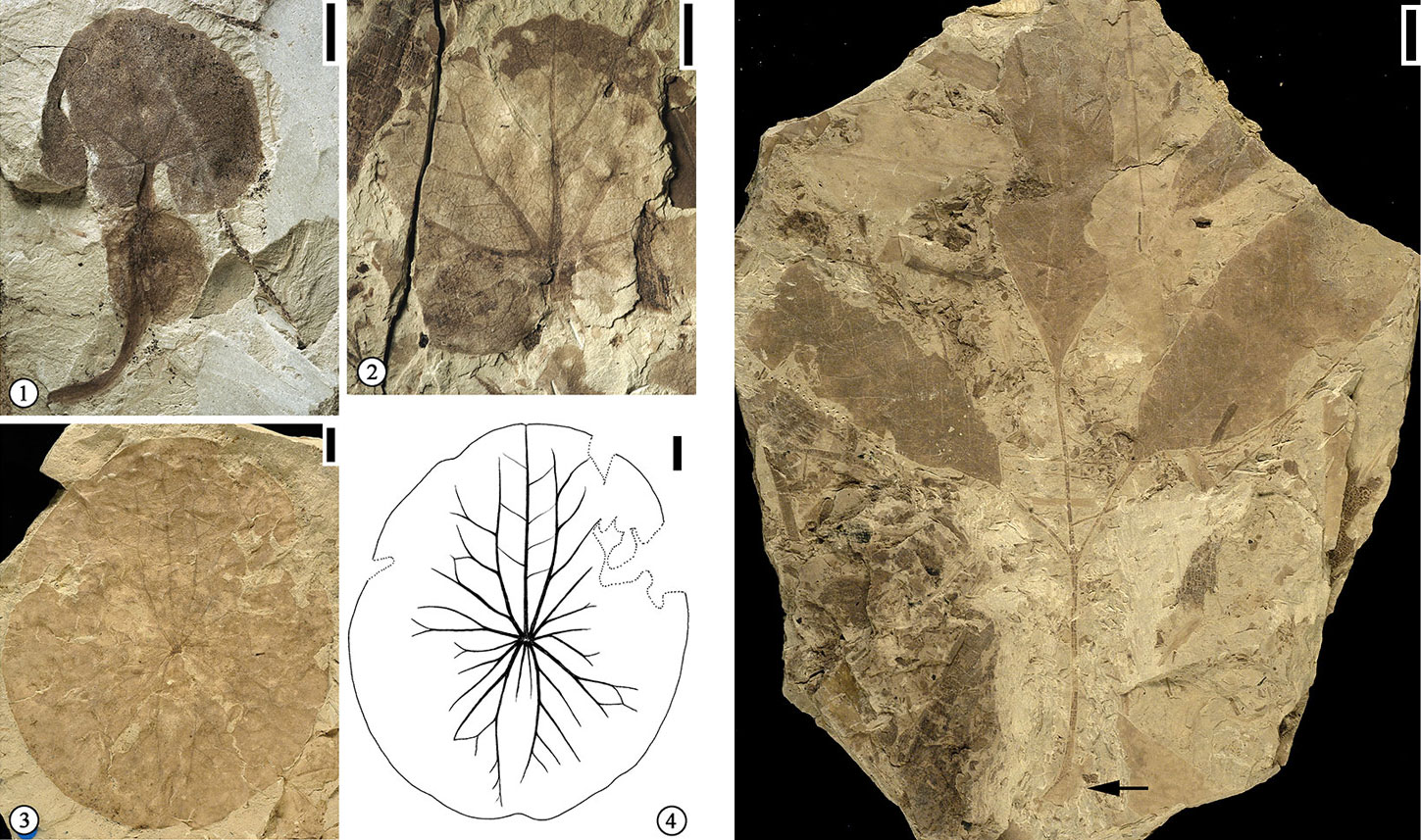

Angiosperm (flowering plant) leaf fossils from the Lower Cretaceous Dakota Formation, Barton County, Kansas. Left: Leaves of aquatic plants, including Aquatifolia fluitans (1, 2, scale bar = 5 millimeters) and Brasenites kansense (3, 4, scale bar = 1 centimeter). Right: Compound leaf of Sapindopsis powelliana (scale bar = 1 centimeter) Source: Figures 5 and 16 from H. Wang and D. L. Dilcher (2018) Palaeontologia Electronica 21.3.34A (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Some spectacular fossils, notably ammonites, occur in the Late Cretaceous Carlile Shale that occurs in a northeast-to-southwest oriented exposure in central Kansas. The most well-known Cretaceous fossils, however, are found in western Kansas chalk, a carbonate rock made up primarily of the fossils of microscopic marine algae called coccolithophores. Today, chalk accumulates mainly in the deep sea. During the Cretaceous, when sea levels were much higher than today, chalk accumulated in shallow inland seas in both North America and Europe; these shallow seas were only about 100–300 meters (328–984 feet) deep. The Cretaceous period is named for the abundance of chalk that accumulated during this time (the Latin word for chalk is creta).

An ammonite (Prionocyclus hyatti), Upper Cretaceous Carlile Shale, Smith County, Kansas. Photo of KUMIP 143746, specimen from Kansas University, Lawrence (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

An ammonite (Scaphites hattini), Upper Cretaceous Carlile Shale, Mitchell County, Kansas. Photo of KUMIP 108807, specimen from Kansas University, Lawrence (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

Outcroppings of the Cretaceous Niobrara Formation at Monument Rocks in western Kansas. Photograph by Vincent Parsons (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

In the Western Interior Seaway, chalk formed in marine environments with relatively little wave or current energy, and on seafloors where dissolved oxygen concentrations were low. This led to conditions that were not particularly favorable for bottom-living organisms, but that were exceptionally good for preserving whatever died there.

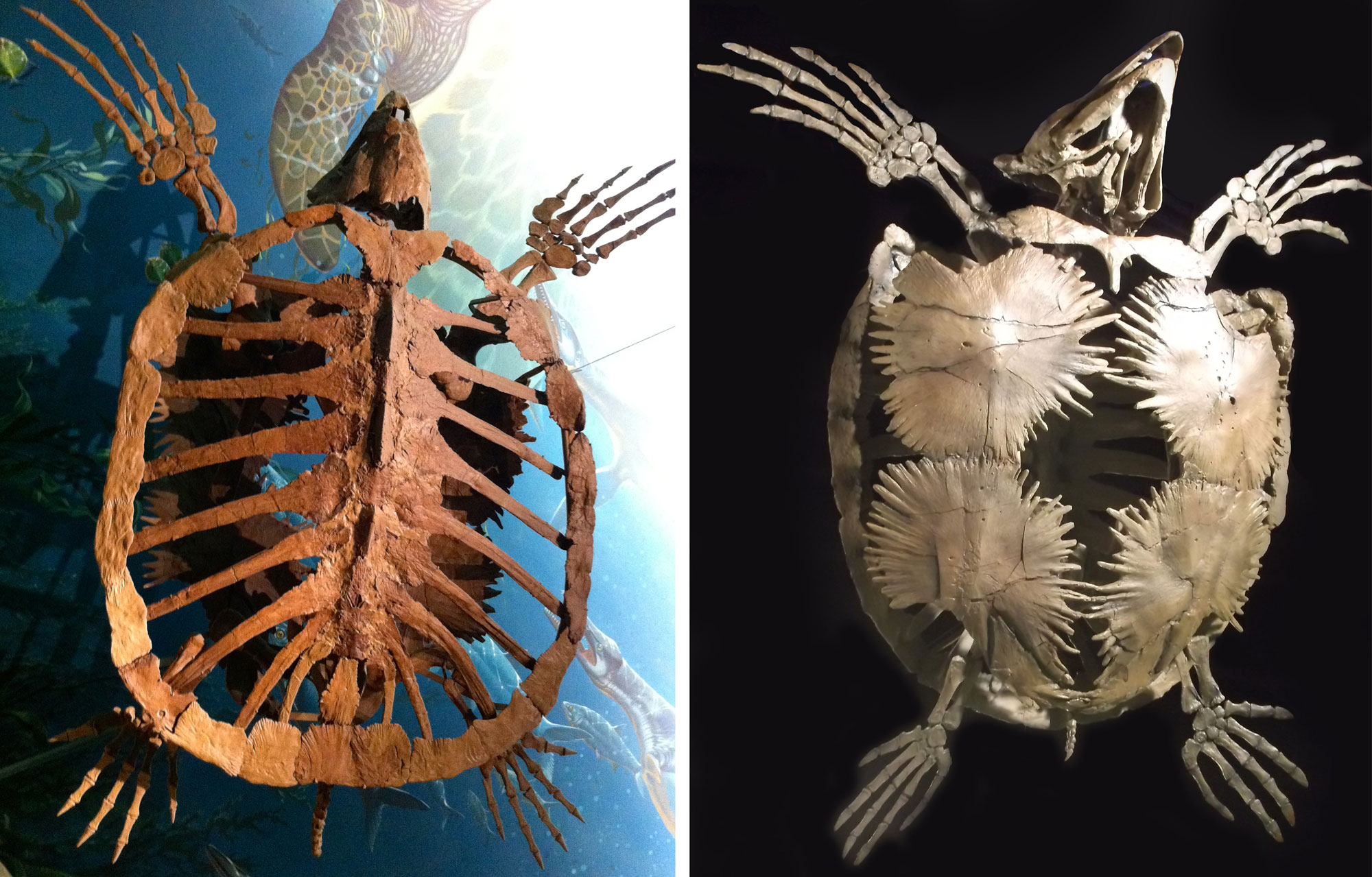

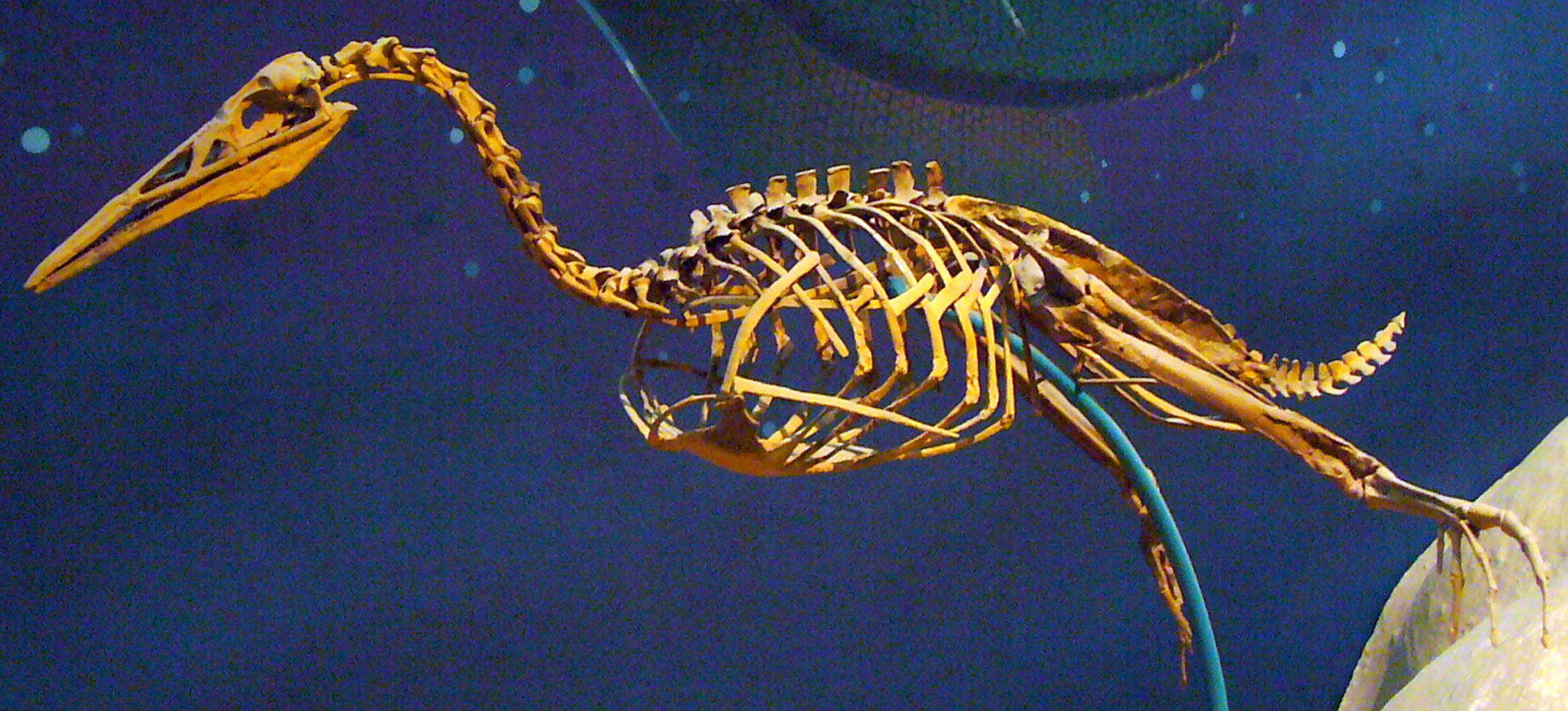

The Niobrara Chalk Formation of Kansas—especially its Smoky Hill Chalk Member (a member is a subdivision of a formation)—is famous for its spectacularly preserved marine vertebrates, including mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, giant turtles, sharks, and other fishes (such as the enormous Xiphactinus). It also preserves pterosaurs (an extinct group of flying reptiles), and diving birds. Interestingly, coprolites (fossilized feces) are also fairly common.

The few benthic (seafloor-dwelling) organisms that were able to tolerate the low oxygen levels include the stalkless crinoid Uintacrinus as well as rudist and inoceramid bivalves. Other invertebrates include ammonoids and gastropods.

Skeleton of Platecarpus tympaniticus, a mosasaur from the Niobrara Chalk of Logan County, Kansas. Scale bar is 0.5 meters (about 1.6 feet), specimen is 5.67 meters (about 18.6 feet) long. Photo of specimen LACM 128319, specimen in the collections of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, fig. 1 from J. Lindgren, M. W. Caldwell, T. Konishi, and L. M. Chiappe (2010) PLoS ONE 5(8): E11998 (Creative Commons Attribution license).

Skull of Clidastes liodontus, a mosasaur from the Niobrara Chalk of Logan County, Kansas. Photo of specimen NMNH V11719, National Museum of Natural History, Paleobiology Department, Smithsonian Institution (public domain).

Skeleton of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a plesiosaur from the Niobrara Chalk of Logan County, Kansas. Photo of Sternberg Museum (Fort Hayes, Kansas) display specimen FHSMVP 404 by Jonathan R. Hendricks (Earth@Home, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License).

Skull of Styxosaurus snowii, an elasmosaur from the Niobrara Chalk, Kansas. Photo of KUVP 1301, specimen on display at the Kansas University Natural History Museum, Lawrence, Kansas, by Neil Pezzoni (Fanboyphilosopher, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Two views of Protostega gigas, from above (left) and below (right). This turtle could grow up to about 3.7 meters (12 feet) long and weigh up to about 900 kilograms (2000 pounds)! The specimen on the left is from the Niobrara Chalk in Gove County, Kansas. The specimen on the right is a reproduction (no locality for the original given, but probably Niobrara Chalk). Photo credit, left image: RaviSarma (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 unported license, image cropped and resized). Photo credit, right image: McDinosaurhunter (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 unported license, image cropped and resized).

Shark teeth and fish bones, Niobrara Formation, Kansas. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Large fish (Xiphactinus audax) with a small fish preserved in its gut. This famous "fish-within-a-fish" specimen was excavated by the fossil collector George Sternberg from the Niobrara Chalk, Gove County, Kansas, in 1952. It is on display at the Sternberg Museum in Fort Hayes, Kansas. Photo of FSHVP 333 from Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License).

A pterosaur (Pteranodon occidentalis) from the Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk, Logan County, Kansas. Source: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History specimen USNM V12167 (public domain).

A bird (Hesperornis regalis) from the Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk, Logan County, Kansas. Source: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History specimen USNM V4978 (public domain).

Crinoids (Uintacrinus socialis) from the Niobrara Chalk, Kansas. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 236986 from Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License).

Rudist bivalves (Durania maxima) from the Niobrara Chalk (Smoky Hill Member), Kansas. Rudists are a group of bizarre reef-forming bivalves. This specimen includes 21 different animals. In life, each would have had a "lid" formed by the second part (valve) of the shell. Photo of Sternberg Museum (Fort Hayes, Kansas) display specimen FHSMIP 1136 by Jonathan R. Hendricks (Earth@Home, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License).

Oysters from the Niobrara Chalk, Kansas. Left: A giant oyster (Platyceramus platinus). Specimen on display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (Colorado), photo by Jonathan R. Hendricks (Earth@Home, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License). Right: A portion of a giant oyster (Platyceramus platinus) shell encrusted with smaller oysters (Pseudoperna cogesta) taken in the field at the Castle Rock chalk badlands. Photo by and information from James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Cretaceous fossils of Oklahoma and Texas

In Texas, extensive Cretaceous outcrops are preserved in the Edwards Plateau. There, limestone units produce a host of marine invertebrate fossils. Ammonoids, gastropods, bivalves (including reef-forming rudists), echinoderms, corals, and petrified wood (in layers formed on or near land) may also be found. Rare fossil fish, dinosaur, pterosaur, and various marine reptile bones have been found along the Great Plains side of the Balcones Escarpment.

The bivalve Arctica compacta from the Upper Cretaceous Buda Limestone Formation, Travis County, Texas. Photo of UT 40526 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

The ammonoid Hypoturrilites tuberculatus from the Upper Cretaceous Buda Limestone Formation, Travis County, Texas. Photo of UT 42852 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

The echinoderm Hemiaster calvini from the Upper Cretaceous Grayson Marl Formation, Bell County, Texas. Photo of University of Texas, Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology specimen BEG 21268 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

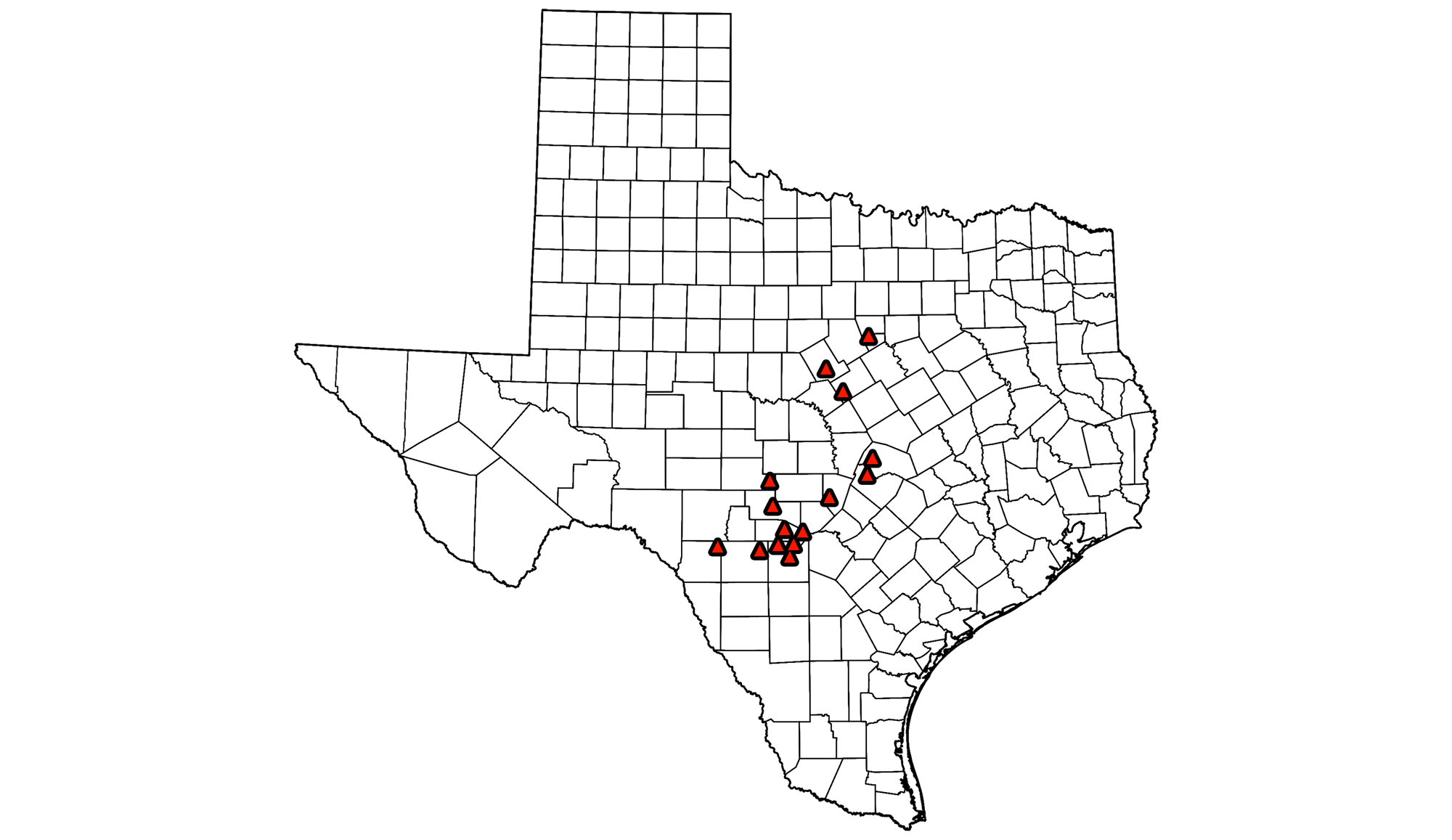

The most famous fossil remains in this area, however, are dinosaur trackways found in more than a dozen locations on and north of the Edwards Plateau. The variety of footprints is attributed to theropods, ornithiscians, and sauropods, though the precise species are impossible to know. Some of the theropod footprints may have been made by Acrocanthosaurus, one of the largest known carnivorous dinosaurs. Skeletal remains of Acrocanthosaurus have been found in Lower Cretaceous rocks in Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming (see a picture of an Acrocanthosaurus skeleton on the South-central U.S.: Fossils of the Coastal Plain page).

Sites in Texas where dinosaur footprints are known. Map by Wade-Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the South Central US.

The therpod dinosaur track, Dinosaur Valley State Park, Glen Rose, Texas. Photo by Diane Turner (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Digital fly-through of a trackway on the Paluxy River that was excavated by Roland T. Bird in 1940. This trackway is interpreted as preserving a chase, with a predatory theropod dinosaur chasing a saurpod (long-necked herbivorous dinosaur). The trackway was about 9 meters (about 29.5 feet) long. This movie was made using historical photos; after the photos were taken, the tracks were removed and distributed to museums. Move S1 from P. L. Falkingham, K. T. Bates, and J. O. Farlow (2014) PLoS ONE 9(4): e93247 (via Figshare, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Cenozoic fossils

In the Late Cretaceous, the Western Interior Seaway retreated and the Rocky Mountains rose to the west; streams carried gravel, sand, and silt that eroded from these newly formed mountains. The sediments filled wide, shallow valleys to create a broad, gently dipping plain that contains a variety of terrestrial and freshwater fossils, including gastropods, clams, algae, and the occasional plant.

By the middle Eocene, the environment became wetter and cooler. Mammals were the dominant animals on land, including a mix of extinct, extirpated, and extant animals that would look out of place in North America today. The Miocene-Pliocene Ogallala Group of Kansas and Oklahoma has produced abundant remains of rodents, horses, and land tortoises, among others.

Pleistocene deposits of central Texas have yielded the bones of sloths and glyptodonts, among other forms.

An extinct North American rhinoceros (Teleoceras fossiger), Miocene, Kansas. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Skull of a gomphothere, an extinct animal related to elephants, from the Miocene, Clarendon region, Texas. Photos of specimen on display in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Ohio. Left photo and right photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central United States: Fossils of the Great Plains (includes more about fossils Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-gp/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern United States: Fossils of the Great Plains (includes more about fossils of the Great Plains in eastern Colorado and New Mexico): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/fossils-gp

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/