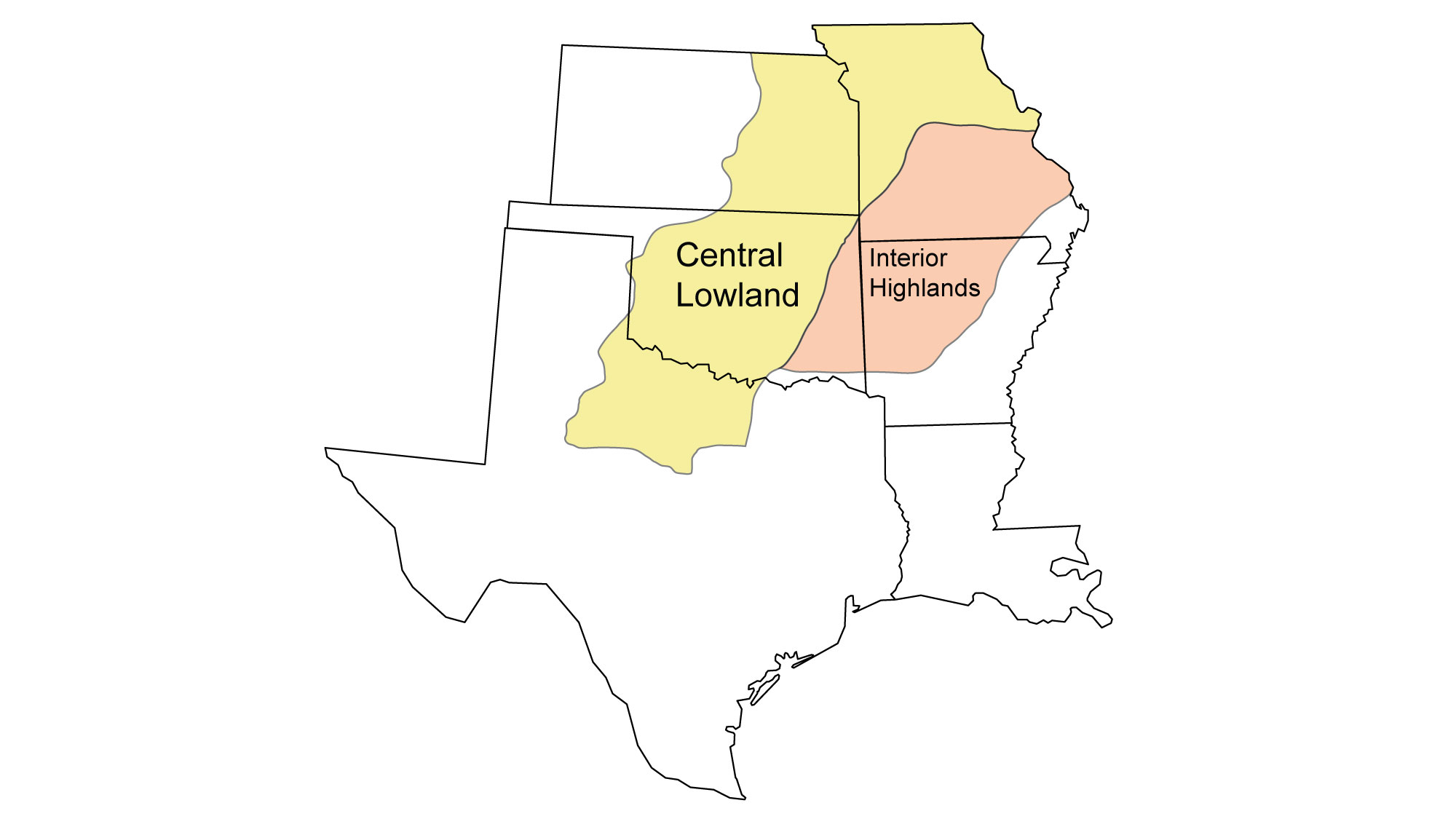

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Central Lowland and Interior Highlands regions of the south-central United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Paleozoic marine animal fossils; Cambrian marine animal fossils; Ordovician marine animal fossils; Devonian marine animal fossils; Mississippian and Pennsylvanian marine animal fossils; Permian marine animal fossils; Paleozoic terrestrial fossils; Pennsylvanian plant fossils; Kansas lagerstätten; Terrestrial fossils of Oklahoma and Texas; Mesozoic fossils; Triassic terrestrial vertebrate fossils; Cretaceous marine invertebrate fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the South Central US" by Warren D. Allmon and Alex F. Wall, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the South Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 25, 2023.

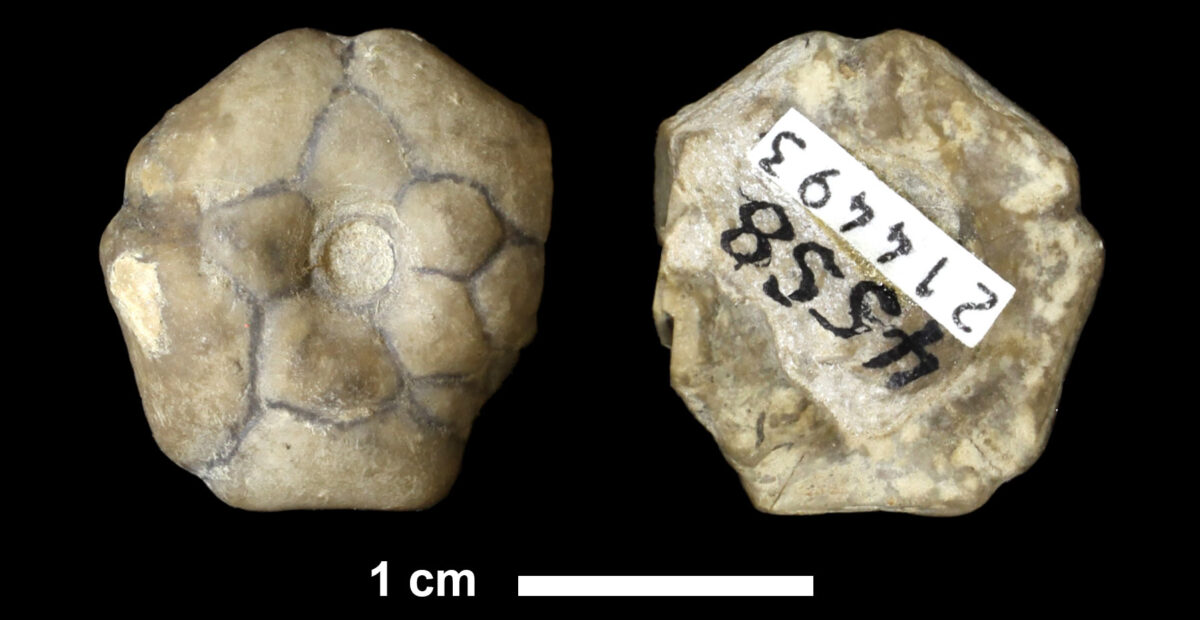

Image above: An echinoderm, Plaxocrinus crassidiscus, Pennsylvanian, Wyandotte Limestone, Jackson County, Missouri. Photo of KUMIP 214493 (Pennsylvanian Atlas of Ancient Life, Midcontinent United States, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Paleozoic fossils

The geological core of the Interior Highlands and Central Lowland regions is formed by a Proterozoic mountain range that formed around 1.5 billion years ago. Today, these igneous and metamorphic rocks crop out in the St. Francois Mountains across an area of around 13,000 square kilometers (5000 square miles) in southeastern Missouri. During the Paleozoic, this ancient mountain range formed an archipelago of islands and seamounts ringed by coral reefs in vast inland seas. Sandstone and limestone were deposited near the shore, while shale formed in deeper water. The sediments accumulating in these shallow seas preserved an abundant record of the marine animals that lived there during the early Paleozoic.

Marine animal fossils

Cambrian fossils

In southeastern Missouri, the Upper Cambrian Lamotte Sandstone formed in a near-shore environment and contains brachiopods and mysterious trace fossils called Climactichnites. Climactichnites is thought to have been made by large mollusks, perhaps similar to gastropods (snails). Other Cambrian rocks in Missouri contain trilobites and hyoliths.

Strabops thacheri, a strabopid (a type of extinct marine arthropod) from the Cambrian of St. Francois County, Missouri. Photo of YPM IP 009001 by Susan H. Butts, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, via GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Ordovician fossils

Fossils from the Ordovician rocks of the Ozarks in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas include many mollusks, such as gastropods (snails), bivalves (mollusks with two-valved shells, like clams), cephalopods (relatives of squid and octopuses), and monoplacophorans. (Monoplacophorans are animals with one cap- or cone-shaped shell, which, in some forms, is somewhat coiled back on itself.) Brachiopods, trilobites, corals, bryozoans, and echinoderms—including crinoids, cystoids, and sea stars—are also found here. In southeastern Missouri, Ordovician rocks have produced the remains of conodonts—primitive vertebrates with small, eel-like bodies and complex arrangements of teeth. Conodonts are very important index fossils for rocks of this age.

Mollusks from the Ordovician of Missouri. Left: Top and side views of a gastropod (snail), Eotomaria depressa (YPM IP 017146), lower Ordovician Cotter Formation, Jefferson County, Missouri. Right: Shell of an unidentified cephalopod (YPM IP 332810) broken to show inner champers and central siphuncle. Middle Ordovician Plattin Limestone, Cape Girardeau County, Missouri. Photos by Jessica Utrup (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

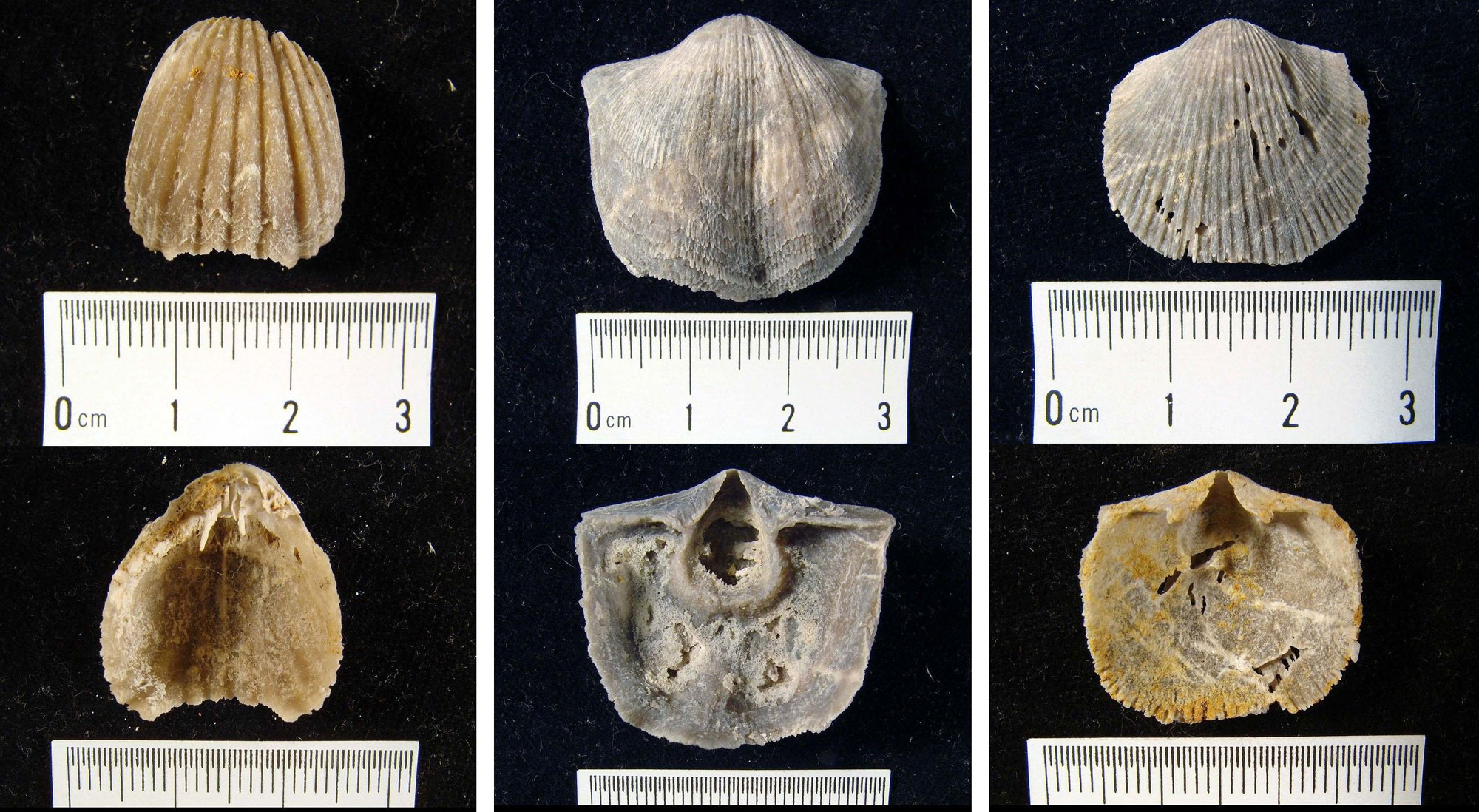

Brachiopods from the upper Ordovician Fernvale Formation, Cape Girardeau, Missouri. In each panel, the upper image shows the outside of the shell, and the lower image shows the inside. Left to right, Rhynchotrema manniensis (YPM IP 068498), Herbertella sinuata (YPM IP 068509), and Austinella whitfieldi (YPM IP 068507). All photos by Jessica Utrup (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Ordovician trilobites. Left: Isotelus iowensis from Missouri. Right: Homotelus bromidensis from Oklahoma. Photos of specimens held by the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI 1388 and PRI 45505) by Wade Greenberg-Brand.

Three views (top, side, and oblique) of a tabulate coral (Columnaria halli, YPM IP 068365) from the middle Ordovician Plattin Limestone, Cape Girardeau County, Missouri. Photo by Jessica Utrup, 2013 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Devonian fossils

The oldest rocks in the Central Lowland are Devonian deposits in southwestern Missouri and eastern Oklahoma. Marine invertebrates, such as corals, trilobites, crinoids, and cephalopods, shared the waters with fishes including shark-like acanthodians. After the mass extinction in the late Devonian, trilobites never regained their previous abundance and diversity, and post-Devonian trilobites are relatively rare. In the Mississippian of Missouri and the Pennsylvanian of Texas, however, small trilobites are locally common (there are photos of some Pennsylvanian trilobites further down on this page).

Trilobites from the lower Devonian Haragan Limestone, Coal County, Oklahoma. Left: Kettneraspis williamsi (YPM IP 428842). Right: Reedops deckeri (YPM IP 531078). Photos by Jessica Utrup (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Mississippian and Pennsylvanian (Carboniferous) fossils

Mississippian limestone beds in Missouri and Arkansas preserve the inhabitants of an ancient reef system, including corals, bryozoans, brachiopods, and fishes. Abundant echinoderms are also present, including blastoids, crinoids (such as Missouri’s state fossil, Delocrinus missouriensis), and large echinoids (sea urchins). The Mississippian is sometimes called “the age of crinoids” because they were so abundant in the shallow seas of this period.

Calyx, arms, and stalk of Cyathocrinites deroseri, Mississippian, Burlington Limestone, Missouri. Scale bars are in millimeters (10 millimeters = 1 centimeter = 0.4 inches). Photo of USNM PAL 509798 (Natural History Museum, Smithsonian Instituion, public domain).

A slab with individuals of the extinct echinoid Melonechinus multiporus, Mississippi (Early Carboniferous), St. Louis Limestone), St. Louis region, Missouri. Tape measure is labeled in inches. Photo of YPM IP 035046 by Brian T. Roach (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Mississippian and Pennsylvanian rocks in Missouri, western Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma contain ammonoids and graptolites, both pelagic groups (animals that lived in the water column rather than on the seafloor) that were once common and diverse but are now extinct. The marine deposits in western Missouri, eastern Kansas, and Oklahoma contain abundant brachiopods, ammonoids, bivalves, gastropods, bryozoans, echinoids, crinoids, corals, and trilobites. The horseshoe crab Paleolimulus is known from Kansas.

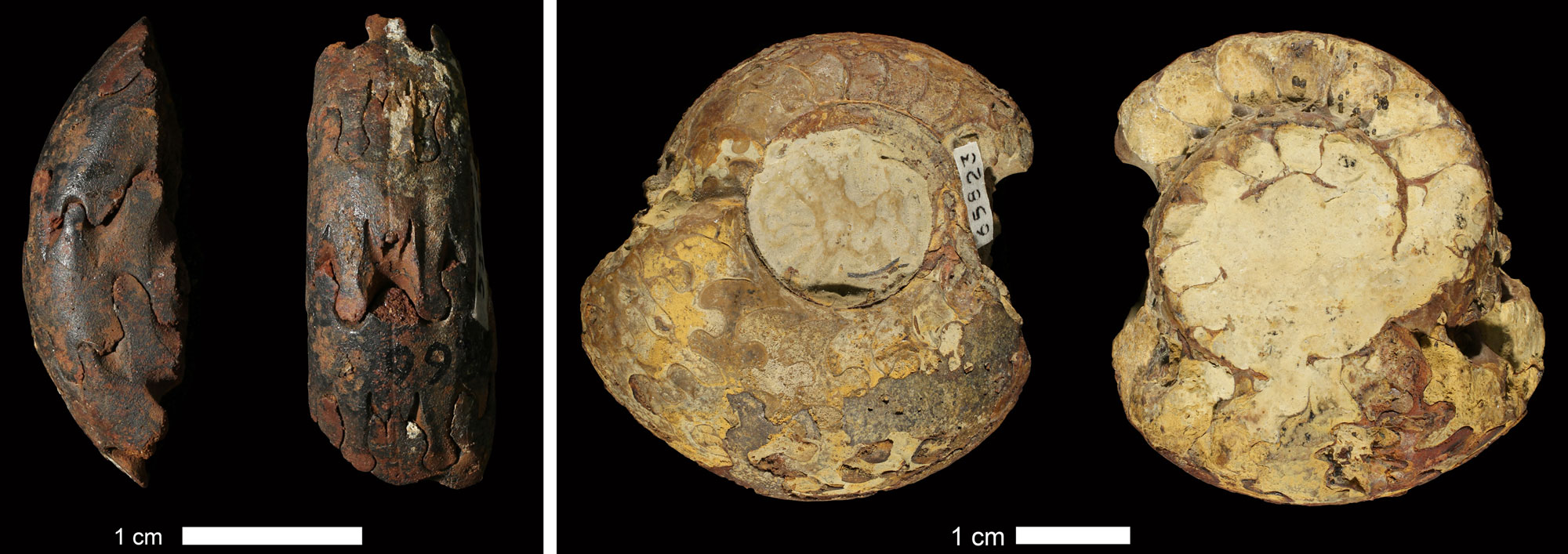

Pennsylvanian ammonoids. Left: Pronorites sp., Atoka Formation, Coal County, Oklahoma. Right: Shumardites cuyleri, Graham Formation, Jack County, Texas. Photos of KUMIP 51218 (left) and KUMIP 65823 (right), Pennsylvanian Atlas of Ancient Life, Midcontinent United States (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

3D model of a gastropod (Worthenia tabulata), Pennsylvanian Vamoosa Formation, Osage County, Oklahoma. Length approximately 3 cm (about 1.2 inches). Model of PRI 45535 by Emily Hauf, held in the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution (Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

3D model of a bryozoan (Archimedes oweniana), Mississippian Keokuk Limestone, Pike County, Missouri. Length approximately 10.5 cm (about 4 inches). Model of PRI 45535 by Emily Hauf, held in the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution (Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Theca of a blastoid (Pentremites, a type of echinoderm) from the Pennsylvanian of Cherokee County, Oklahoma, in top (left) and side (right) views. Photos of YPM IP 030116 by Jessica Utrup, 2013 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Pennsylvanian trilobites from Kansas. Left: Cephalon (head) of Ameura major, Topeka Limestone, Wyandotte County. Right: Phillipsa sp., Dennis Limestone, Neosho County, Kansas. Photos of KUMIP 307854 (left) and KUMIP 146443 (right), Pennsylvanian Atlas of Ancient Life, Midcontinent United States (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

3D model of a fossil horseshoe crab (Paleolimulus signatus), Carboniferous, Kansas. Ohio State University specimen, length approximately 6.5 cm (2.6 inches). Model by Emily Hauf (Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Limestone containing fusilinids, Pennsylvanian Iola Formation, Kansas. Fusilinids are a types of large foraminifera. Foraminifera or "forams" are single-celled protists (organisms that are neither plants, animals, nor fungi) with tests, or shells, made out of calcium carbonate. The rock on the left measures about 13.7 centimeters (5.4 inches) in width. Left photo and right photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Permian fossils

The beginning of the Permian saw continued sea level fluctuations, and shallow marine deposits from this time in eastern central Kansas contain faunas similar to those of the Pennsylvanian. As the period continued, however, the climate became much drier, and shallow seas were restricted to central Kansas. To the west of these beds, Permian rocks contain the remains of lungfish, sharks, and other fishes.

Terrestrial fossils

Pennsylvanian fossil plants

In the Pennsylvanian, the sea began to drain away from the Interior Highlands and Central Lowland. Pennsylvanian rocks in northern and western Missouri and eastern Kansas and Oklahoma indicate cyclical fluctuations between shallow marine and terrestrial environments, preserved in repeating layers of shale, limestone, and sandstone interspersed with thick seams of coal. These coal beds, representing terrestrial near-shore swamps, were formed from great thicknesses of decomposing plants.

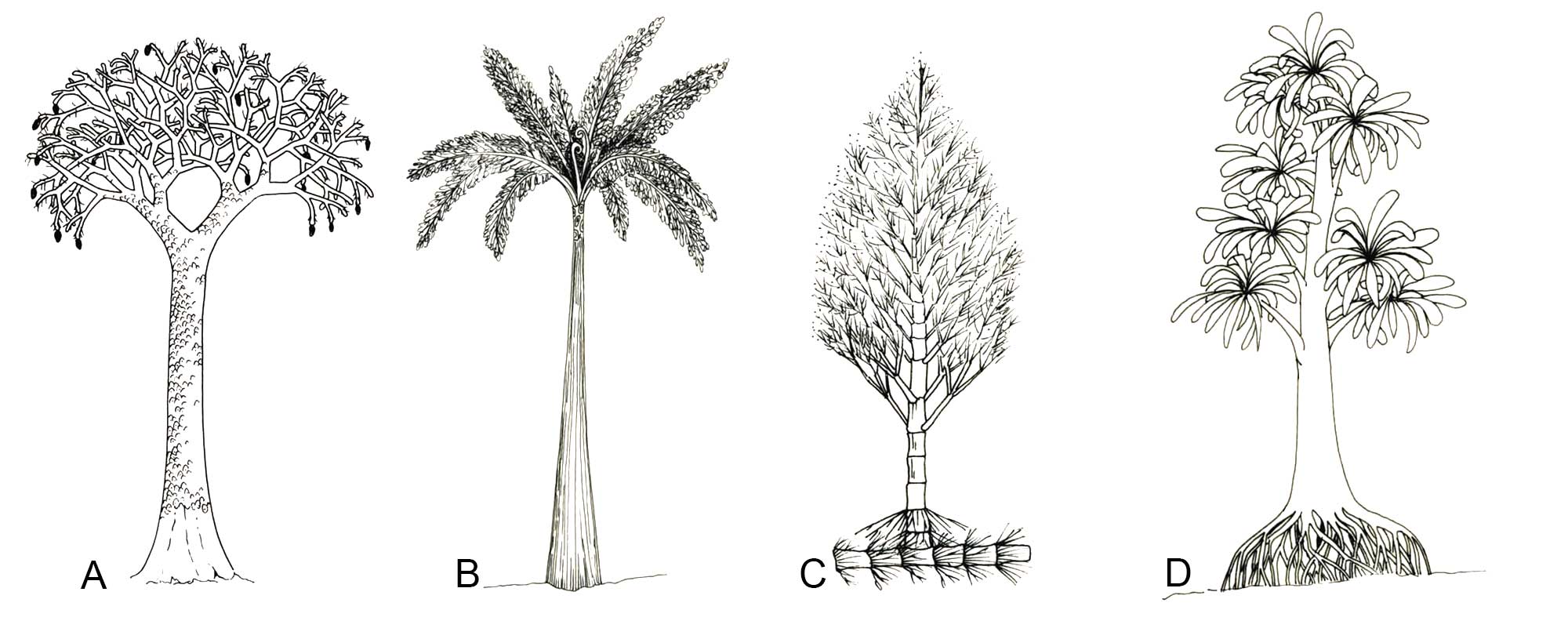

The trees found in these forests did not belong to the familiar groups that dominate modern forests, such as conifers and flowering broadleaf plants. Instead, these early forests were made up of groups of plants that are either extinct or much less conspicuous today. These groups were the lycophytes (club mosses and relatives), the sphenophytes (horsetails and relatives), the marattioid ferns, seed ferns (seed-producing plants with fern-like leaves) and the cordaites (a group related to conifers). Lycophytes and horsetails survive today as small, non-woody plants. Marattioid ferns are restricted to the tropics. Cordaites are extinct.

Restorations of Pennsylvanian coal swamp trees. A. Scale tree (Lepidodendron), a lycopod that reached 30 m (100 ft) tall. B. Psaronius, a marattioid tree fern, reached 3 m (10 ft) tall. C. Calamites, a sphenophyte (horsetail), reached 20 m (65 ft) tall. D. Cordaites, a conifer-like seed plant; reached 10 m (35 ft) tall. Illustration by Christi Sobel.

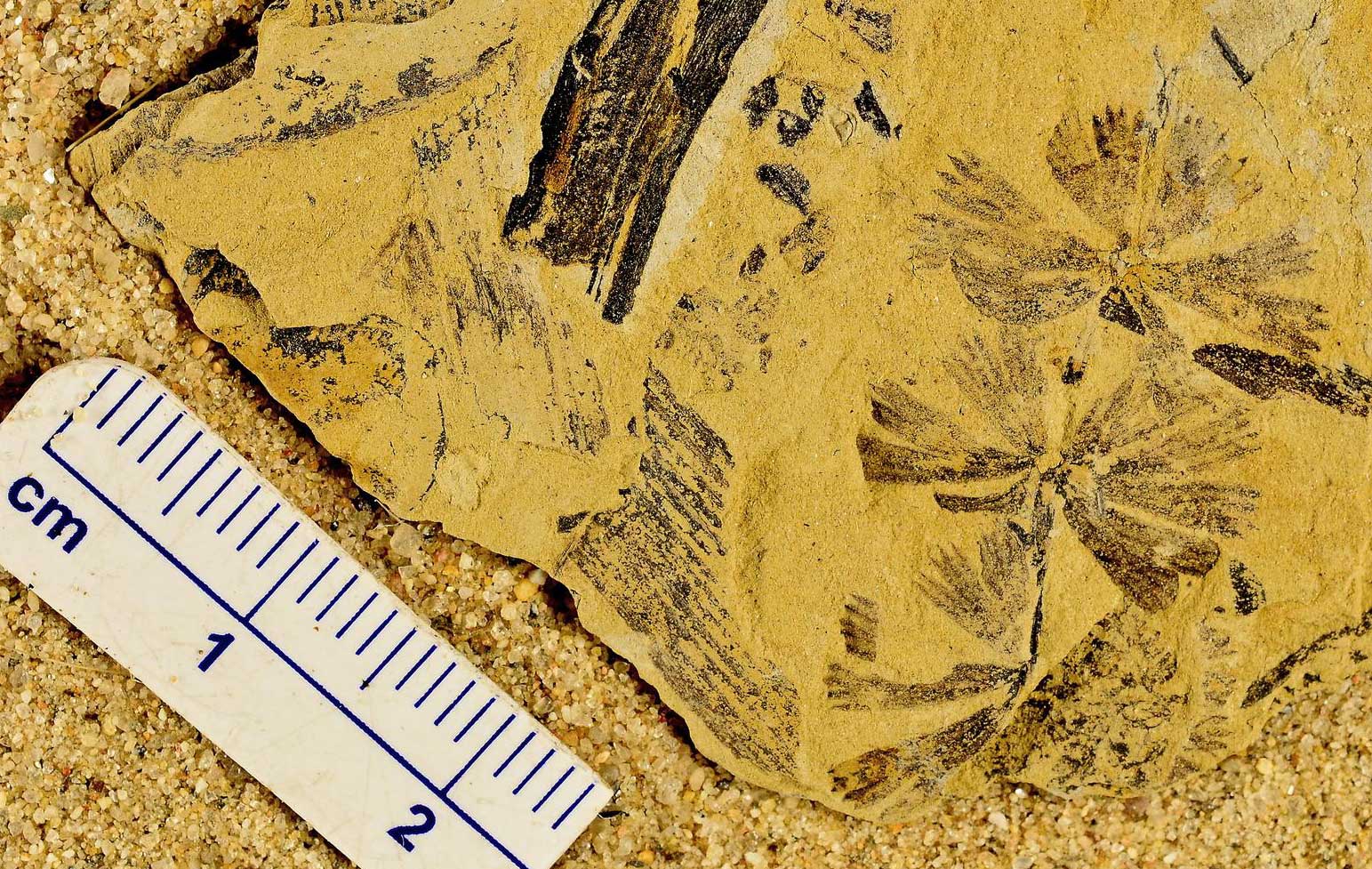

Fossil leaf whorls of Sphenophyllum, a shrubby plant related to modern horsetails (Equisetum), and sphenophyte stem fragments. Pennsylvanian (Late Carboniferous) Lawrence Shale, Lawrence, Kansas. Photo of YPM PB 000750 by Robert Swerling (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

3D model of branches and leaf whorls of Asterophyllites, the foliage of a tree related to modern horsetails (Equisetum). Pennsylvanian (Late Carboniferous) Tonganoxie Sandstone, Franklin County, Kansas. Model of PRI 50619 by Emily Hauf, specimen on display at the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York (Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Kansas lagerstätten

Several fossil lagerstätten deposits (deposits of exceptionally well-preserved fossils) are known from the Pennsylvanian and Permian of Kansas. These deposits, which formed along the shoreline of a shallow sea, contain abundant and beautifully preserved terrestrial tetrapods and insects as well as many marine invertebrates and fish. The Garnett locality in Andersen County preserves an incredible record of life during the Pennsylvanian in a series of stream channel infills. Petrolacosaurus, one of the earliest known diapsid reptiles, can be found at this site.

Petrolacosaurus kansensis fossil foot and reconstruction (inset). Photo of fossil foot by Fanboyphilosopher (Neil Pezzoni, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized). Reconstruction by Nobu Tamura (copyright Nobu Tamura, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

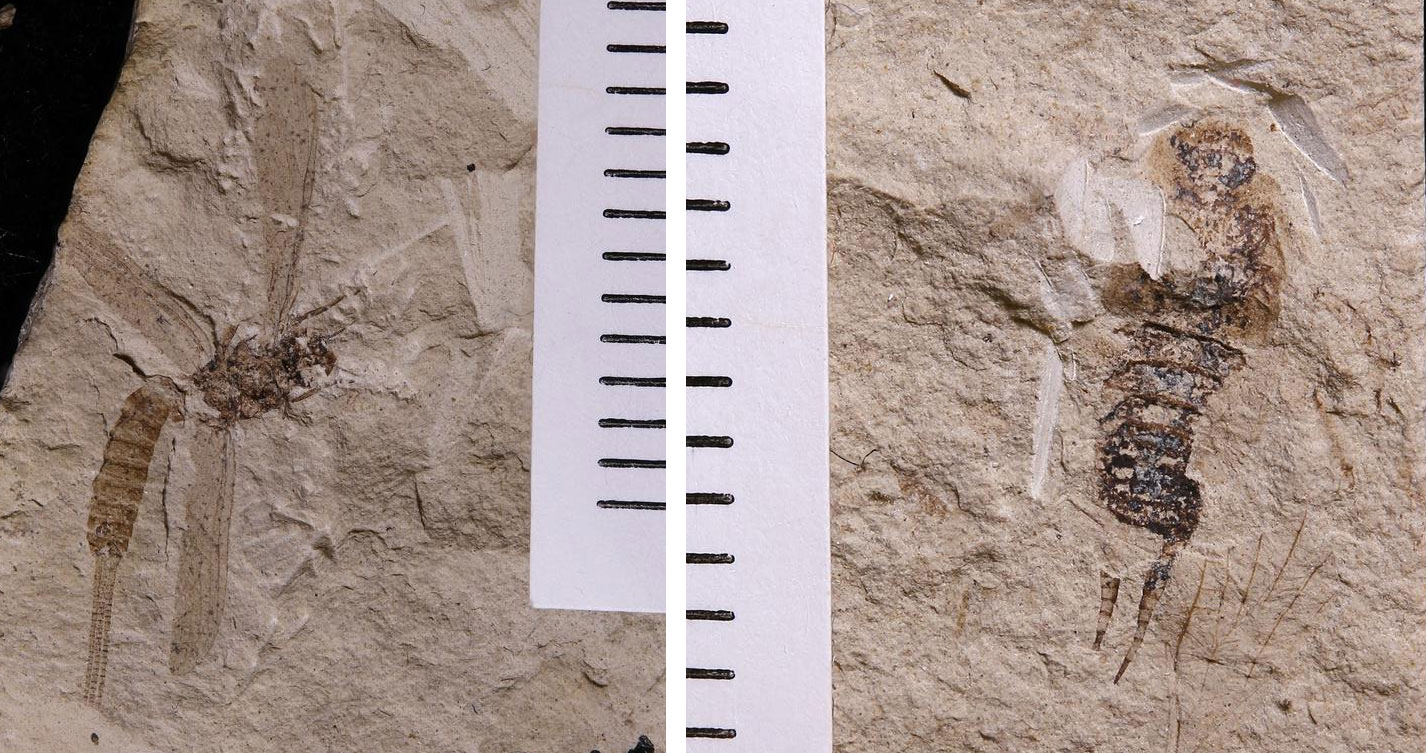

The Elmo Limestone in Dickinson County is famous for its fossil insects and xiphosurids (the group of arthropods that includes horseshoe crabs). Other examples of deposits containing similar faunas include the Robinson locality in Brown County and the Hamilton locality in Greenwood County.

Wing of a griffinfly (giant dragonfly, Megatypus schucherti) from the Permian, Elmo Limestone, Kansas. Photo of YPM IP 001021 by Jessica Utrup, 2015 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Fossil insects from the Permian, Elmo Limestone, Kansas. Left: Mayfly (Eudoter delicatulus, YPM IP 001014). Right: Icebug (Lemmatophora typa, YPM IP 027961). Scales are in millimeters (10 millimeters = 1 centimeter = 0.4 inches). Photos by Elissa S. Sorojsrisom, 2018 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Fossils of Oklahoma and Texas

In Oklahoma and Texas, the shallow sea retreated to the west, and thick layers of gypsum and salt were deposited, indicating that evaporation rates were high. Rare fossils of insects, amphibians, and reptiles, as well as vertebrate footprints, have been collected from the youngest Paleozoic rocks in Oklahoma. The Dolese Quarry near Lawton (Comanche County), for example, has produced a great diversity of tetrapods in soft white claystone, including the common small anapsid reptile Captorhinus aguti.

Captorhinus aguiti, Permian, Dolese Brothers quarry, Comanche County, Oklahoma. Photo by Didier Descouens (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, posting to Facebook prohibited, image cropped and resized).

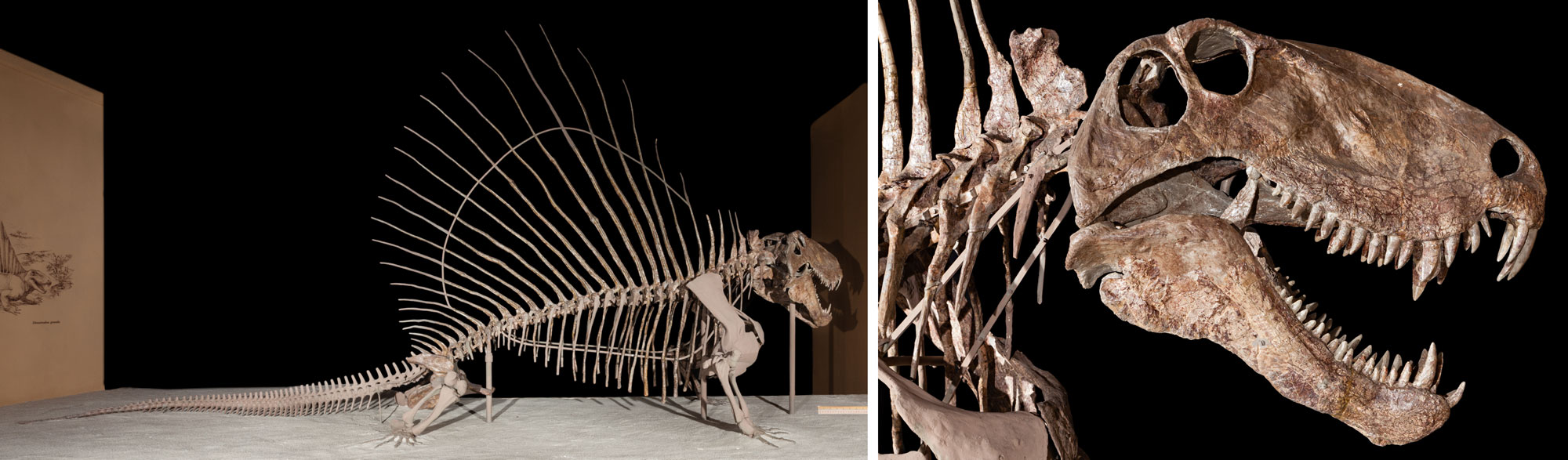

Permian “red bed” deposits in western and north-central Texas (such as the Quartermaster Formation) are famous for their abundance of early Permian reptiles including synapsids—a group that includes the ancestors of modern mammals. Here, well-known tetrapods like the sail-backed Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus, the giant amphibian Eyrops, the bizarre amphibian Diplocaulus, and the enigmatic Diadectes dominate the fauna. Plants also occur, including sphenophytes, seeds ferns, and early conifers.

Dimetrodon grandis, Permian, Clear Fork Formation, Baylor County, Texas. Photos of USNM V 8635 by James Di Loreto (Department of Paleobiology, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Edaphosaurus boagnerges cast (reproduction) skeleton, Permian, Archer City Formation, Archer County, Texas. Photo of USNM V 16647 by James Di Loreto (Department of Paleobiology, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Eryops composite skeleton (a skeleton made up of the bones of more than one animal), Permian, Texas. Photo of USNM PAL 299567 and USNM V 6721 by Michael Brett-Surman (Department of Paleobiology, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, available via GBIF.org).

Diplocaulus magnicornis, a Permian amphibian. Left: Reconstruction of the living animal by Dmitry Bogdanov (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized). Right: Skull of Diplocaulus magnicornis from the Permian, Baylor County, Texas. Photo by James St. John (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Diadectes skeleton Permian, Arroyo Formation, Baylor County, Texas. Photo of USNM PAL 437989 by Michael Brett-Surman (Department of Paleobiology, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, also available via GBIF.org).

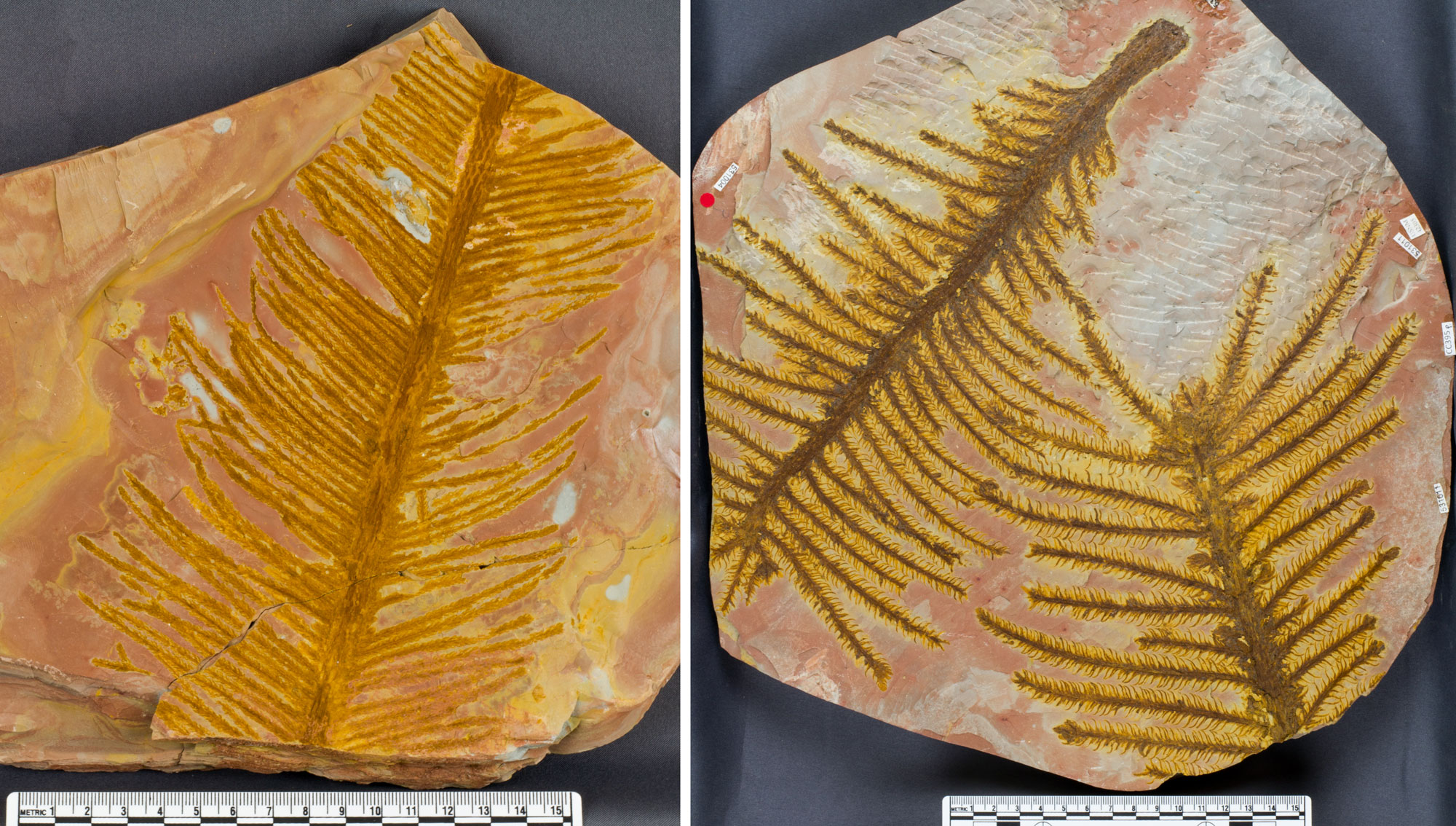

Walchia sp. branches and leaves, Permian, Clear Fork Group, Texas. Walchia is an early, extinct conifer. Photos of USNM 617446 (left) and USNM 531011 (right) by Bruce Martin (Smithsonian Institution, NMNH Paleobiology, public domain).

Taeniopteris sp., a type of leaf from an extinct seed plant. Permian, Clear Fork Group, Texas. Photo of USNM 596270 by Bruce Martin (Smithsonian Institution, NMNH Paleobiology, public domain).

Mesozoic fossils

Triassic vertebrate fossils

A ribbon of fossil-bearing Triassic strata occur above the Permian layers in the western part of the Texas panhandle southeast to near Abilene. The temporal (time) boundary between the Permian and Triassic marks the greatest mass extinction known. While its effect on marine life was particularly devastating, life on land was dramatically affected as well. Many kinds of tetrapods (four-legged vertebrates) disappeared, which may have cleared the path for a new group of tetrapods, the dinosaurs, to dominate the land. (Dinosaurs first appeared in the middle Triassic.)

The Triassic rocks of Texas crop out along the border between the Great Plains and Central Lowland regions. A variety of early dinosaurs are found in here, along with phytosaurs (extinct animals that look like crocodiles, although the two groups are not related), and synapsids (mammal-like reptiles).

Postosuchus kirkpatricki, a Triassic archosaur first described from material found at the Post Quarry site, Garza County, Texas. Photo of a specimen on display at the Museum of Texas Tech University by Dallas Krentzel (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Rutiodon, a phytosaur, Triassic, Dockum Formation, Howard County, Texas. Phytosaurs looked similar to crocodiles. Photo of USNM V 21376 by Michael Brett-Surman (Department of Paleobiology, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Coahomasuchus kahleorum, an extinct aetosaur, Triassic, Howard County, Texas. Aetosaurs are a group of extinct armored reptiles that are distantly related to both phytosaurs and crocodiles. This fossil is a portion of its armor, which is made up individual pieces called scutes or osteoderms. Photo of NMMNH P-18496 (New Mexico Museum of Natural History, via Arctos, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized; also available via GBIF.org).

Cretaceous marine invertebrate fossils

Cretaceous rocks exposed in southern Oklahoma and north central Texas contain a variety of marine mollusks, including bivalves, gastropods, and ammonites.

Ostrea crenulimargo (an oyster, a type of bivalve) from the Cretaceous Glenrose Formation, Montague County, Texas. Photo of University of Texas, Austin, Texas Bureau of Economic Geology specimen BEG 21744 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

Graphaea mucronata (an oyster, a type of bivalve) from the Lower Cretaceous Del Rio Formation, Denton County, Texas. Photo of Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History specimen YPM 537552 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

The ammonoid Oxytropidoceras acutocarinatum from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) Comanche Peak Limestone Formation, Tarrant County, Texas. Photo of Kansas University Museum of Natural History specimen KUMIP 148309 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image modified).

Eopachydiscus marcianus (an ammonoid) from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) Duck Creek Limestone, Marshall County, Oklahoma. Photo of Kansas University Natural History Museum specimen KUMIP 148431 from the Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Macraster elegans (an echinoid) in three views (left to right: top, bottom, and side) from the Lower Cretaceous Fort Worth Limestone (Caddo Formation), Marshall County, Oklahoma. Photo of YPM IP 531880 by Jessica Utrup, 2015 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Cenozoic fossils

Cenozoic rocks are largely absent from this area, and most Cenozoic fossils are Pleistocene in age. Pleistocene gravels in southwestern Oklahoma (Tillman County) have produced the bones of glyptodonts. Pleistocene deposits in Dallas County, Texas, contain the bones and teeth of mammoths and mastodons.

Late Pleistocene mammals are abundant at several localities in Kansas, including along the banks of the Kansas River from Topeka to Kansas City. Several finds have been made in the greater Kansas City area itself for more than the past century.

Bison occidentalis, Pleistocene, Kansas River bed, Wyandotte County, Kansas (near Kansas-Missouri border). Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic, image resized).

Another famous site is the Kimmswick Bone Bed in Jefferson County, eastern Missouri (at Mastodon State Historic Site). This bone bed not only contains abundant fossil mastodon and other bones, but also stone tools made by some of the earliest human residents of this part of North America.

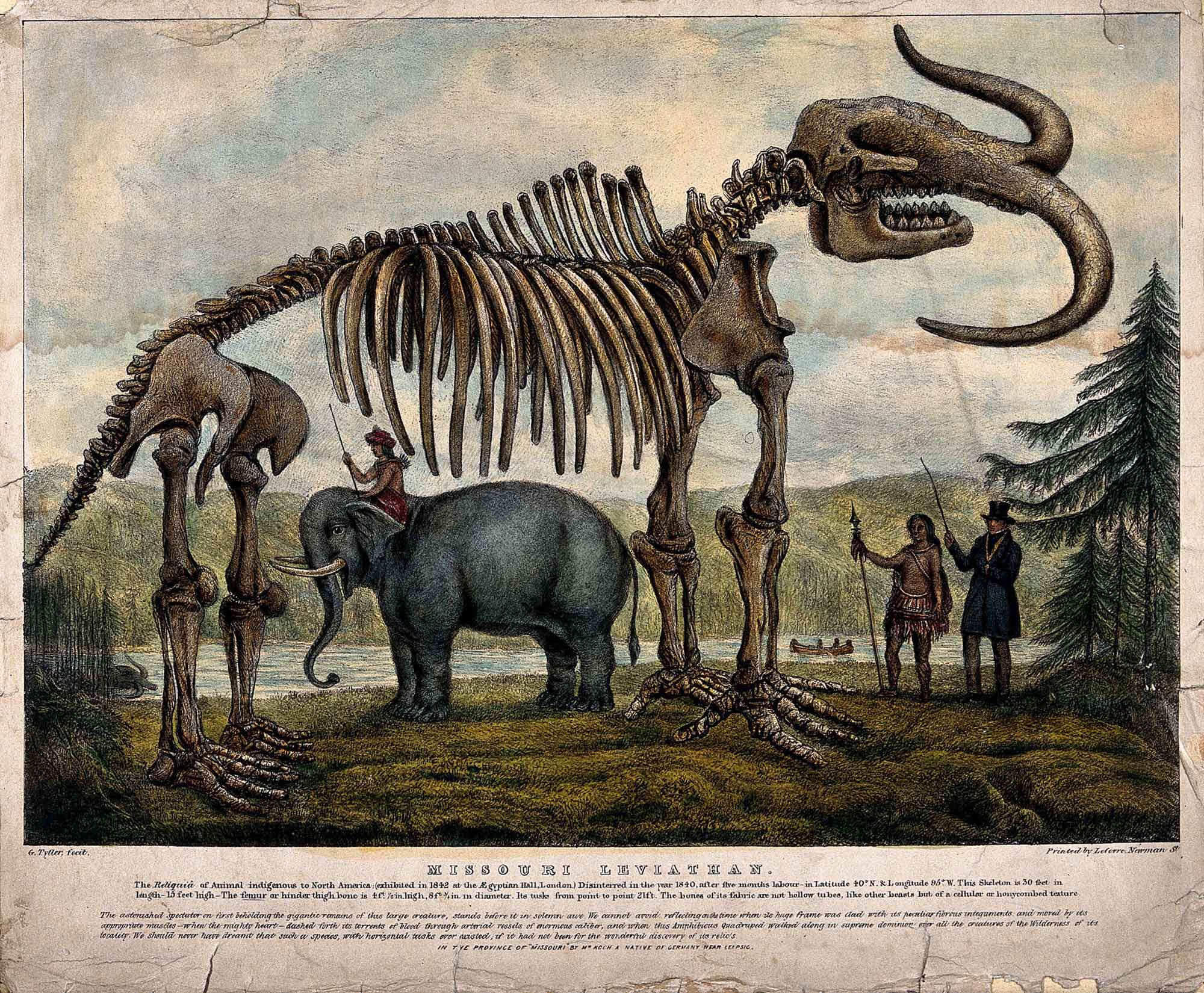

One famous mastodon from the vicinity of Kimmswick was discovered around 1840 and excavated by a showman named Albert Koch. Koch constructed a fanciful skeleton using bones from multiple mastodons; his creation was billed as the "Missouri Leviathan." He included extra bones and other modifications to make his skeleton larger. Koch traveled around North America and Europe displaying the Missouri Leviathan. It was eventually purchased for the British Museum at a hefty price. The skeleton, now accurately reassembled, is on public display in Hintz Hall, Natural History Museum, London, England.

Exhibits at Mastodon State Historic Site in Imperial, Missouri. Photo by Eden, Janine and Jim (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

A lithograph of the Missouri Leviathan by G. Tytler (ca. 1845). The text at the bottom reads in part: "This skeleton is 30 feet in length -15 feet high." In reality, mastodons were smaller than modern African elephants and more comparable in size to Asian elephants. Source: Wellcome Collection (public domain).

The "Missouri Leviathan" mastodon on display at the British Museum in 2017. Photo by Thomas Quine (flicker, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Midwestern U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland (covers the Central Lowland in Illinois, Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin): https://earthathome.org/hoe/mw/fossils-cl

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland and Inland Basin (covers the Central Lowland and Inland Basin in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont): https://earthathome.org/hoe/ne/fossils-cl-ib/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland (covers the Central Lowland in Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-cl

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/

Pennsylvanian Atlas of Ancient Life, Midcontinent United States (Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas): https://pennsylvanianatlas.org/