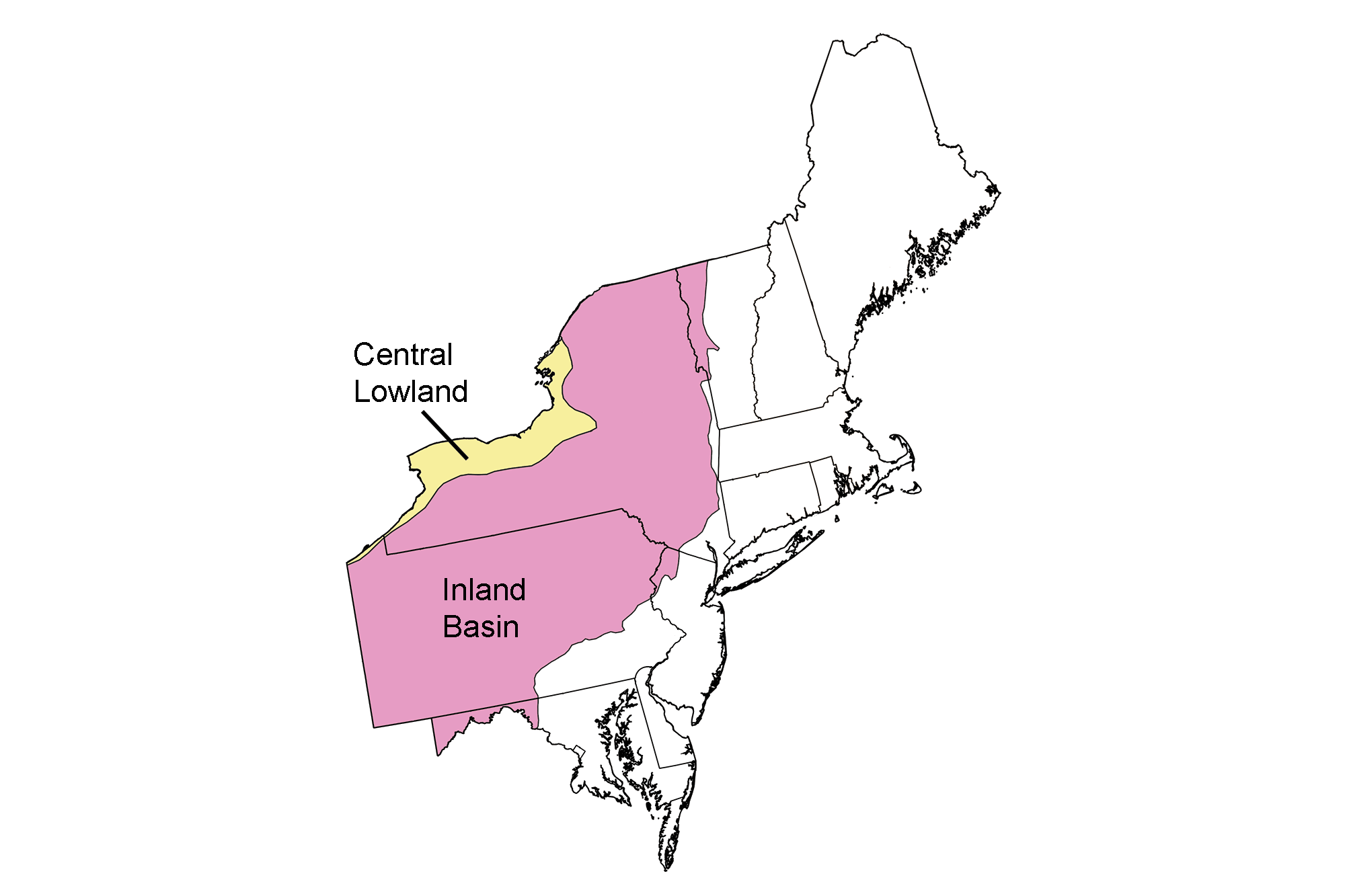

Spotlight: Overview of the fossils of the Central Lowland and Inland Basin regions of the Northeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Cambrian; Stromatolites; Small shelly fossils; Early bivalve Fordilla troyensis; Ordovician; Trenton Group trilobites; Beecher's Trilobite Bed; Chazy Reefs; Silurian; Rochester Shale; Bertie Group; Medina Sandstone; Devonian; Gilboa fossil forest; Catskills freshwater bivalves; Montour Preserve; Glass sponges; Carboniferous; Coal swamp plants; Pleistocene; Terrestrial fossils; Marine fossils; Resources.

Credits: Much of the text of this page began with "Fossils of the Northeastern US: a brief review" by Jane Elizabeth Ansley, from The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US (published in 2000 by the Paleontological Research Institution, reprinted in 2016; currently out of print). The text was adapted for Earth@Home web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2023; major additions and modifications were also made to the text by Warren D. Allmon in 2023. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 25, 2023.

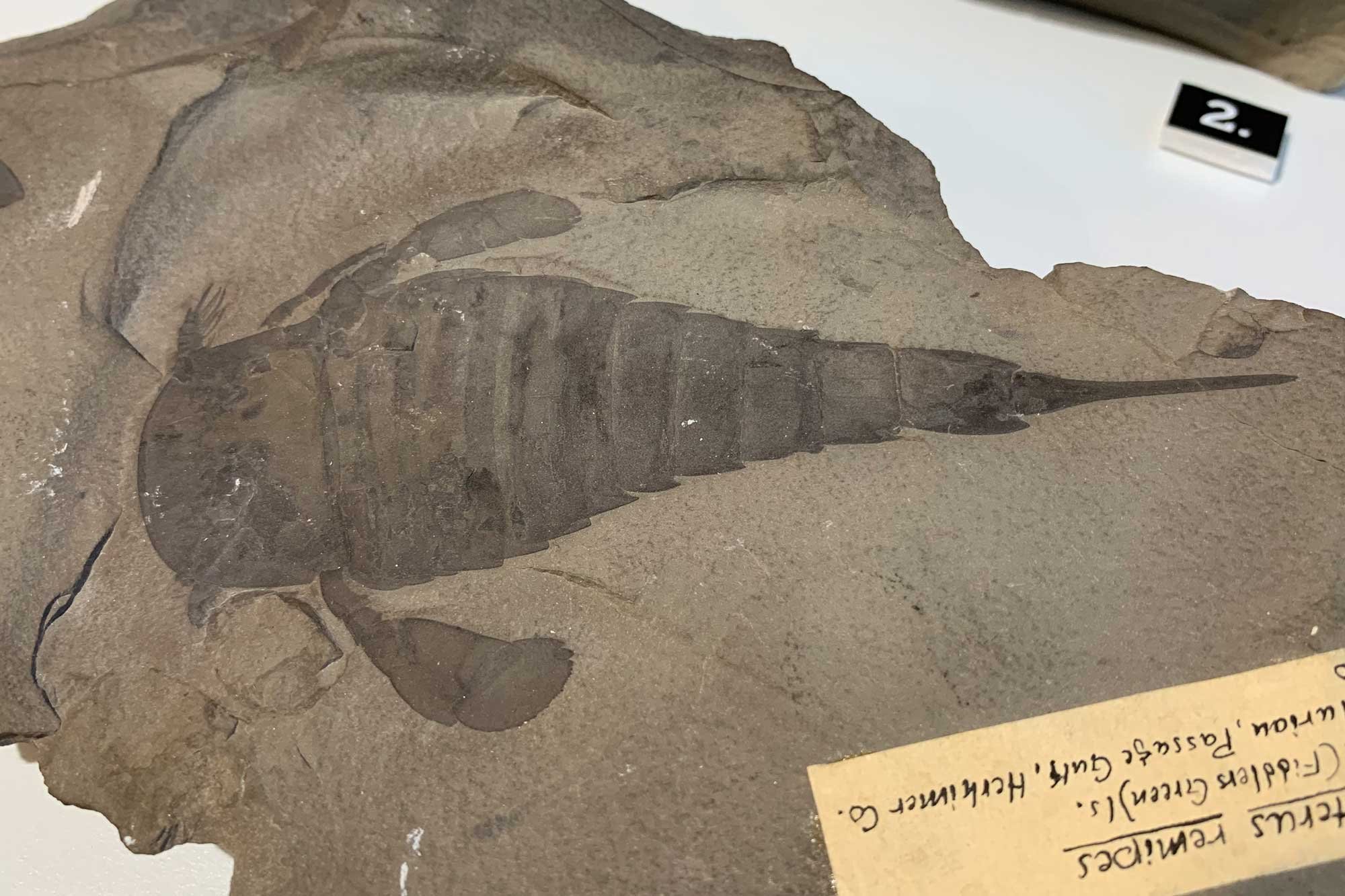

Image above: Model of the eurypterid (sea scorpion) Eurypterus remipes, New York’s official state fossil..

Overview

Fossils from the Inland Basin and Central Lowland regions of the Northeastern U.S. testify to the history of both marine and terrestrial life during much of the Paleozoic Era. This is very dynamic history of environmental change, including extensive mountain-building events associated with the deposition of sediments in an inland epicontinental seas and numerous major and minor changes in relative sea level.

The earliest fossils in the Inland Basin region are “small shelly” and other exceptionally preserved fossils from the Early Cambrian. Younger Cambrian and Ordovician fossil-bearing rocks wrap around the southern margin of the Adirondacks of New York and include spectacular Late Cambrian stromatolites, some of the world’s oldest cephalopods, and some of the best-preserved Ordovician trilobites in the world. Silurian fossils–including New York’s iconic eurypterids (sea scorpions)–are abundant in rocks that extend east-west across New York State south of Lake Ontario. The most extensive fossil-bearing rocks in the region are of Devonian age; these deposits occur widely in New York and Pennsylvania and include ancient biological communities from deep offshore to the braided streams of the giant Catskill Delta. After the Devonian, the sea retreated from the Northeast, and Pennsylvanian-age rocks preserve an excellent record of terrestrial plant life across much of Pennsylvania and adjacent states in the Midwest and Southeast.

Cambrian

Stromatolites

One of the most extensive examples of domal (dome-shaped) stromatolites in the world occurs near Saratoga Springs in Saratoga County, New York. Stromatolites are layered structures formed by microbial mats of cyanobacteria (so-called "blue-green algae," a type of photosynthetic bacteria) that trap and bind sediment. As sediments and minerals accumulate on the mats of microbes, they form characteristic layers, which are sometimes preserved in the rock record. Stromatolites are rare today because they can only form in inhospitable environments (typically, in water with high salt concentrations) that exclude animals that would graze on them. The Cambrian stromatolites are thought to have formed in an environment similar to the modern hypersaline sabkha environments (extremely salty mudflats or sandflats) of the Persian Gulf.

The Saratoga stromatolites are exposed in three locations near Saratoga Springs: Lester Park (a New York State Park and an outdoor exhibit of the New York State Museum), the Petrified Sea Gardens, and an abandoned quarry (the “Skidmore Quarry”) just west of the Skidmore College campus. The Saratoga Springs stromatolites were studied by Winifred Goldring, the first woman to become state paleontologist of New York, who published a paper about them in the 1930s. They were first described in the early nineteenth century as sea plants (algae) and later as sponges (stromatoporoids). They were only recognized as stromatolites in the late twentieth century.

Stromatolites at Petrified Sea Gardens near Saratoga Springs, New York. Photograph by Daniel Case (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

Stromatolite specimens in place (in situ) at Lester Park near Saratoga Springs, New York. Photograph by Scott Johnson (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 generic license).

Stromatolite from the Cambrian Hoyt Limestone from Lester Park, New York. Specimen from the collections of the New York State Museum.

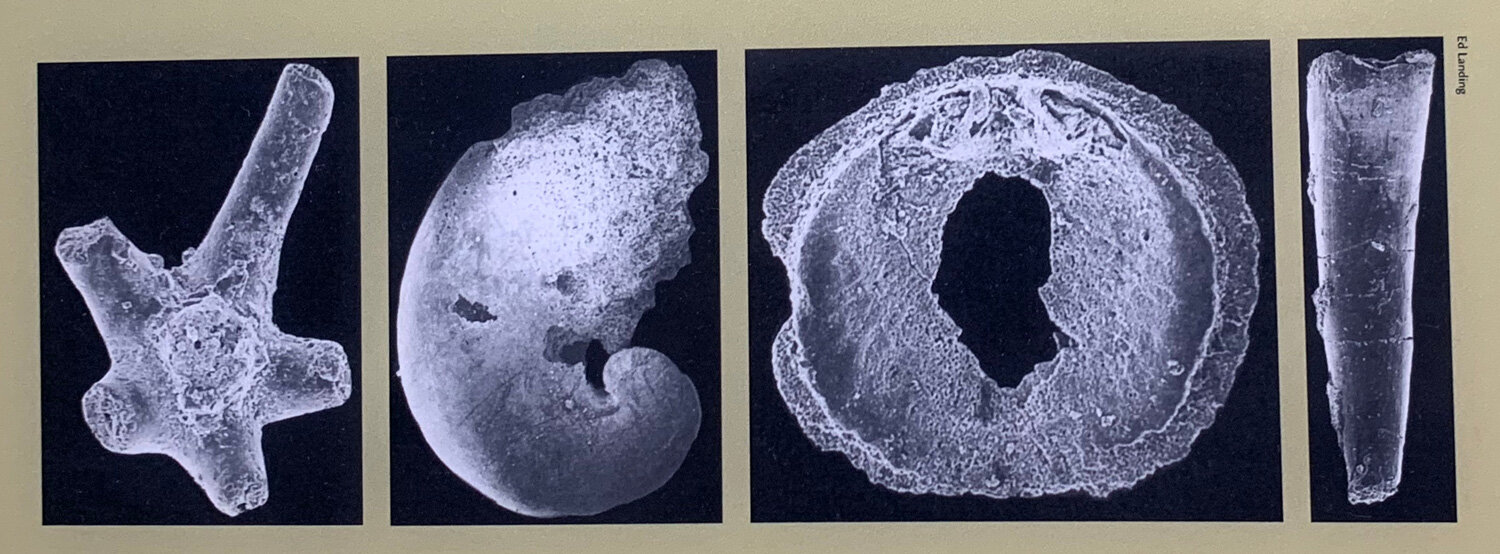

Small shelly fossils

The first mineralized hard parts preserved in the fossil record consist of a puzzling assemblage of tiny skeletal pieces known as “small shellies.” Exactly what these animals were is not completely known, but they might represent bits and pieces of larger animals.

Small shellies have been found in Early Cambrian rocks found near Claverack, Columbia County, in eastern New York. These rocks are part of a block of rocks that was thrust over younger rocks during a collision of an island arc with the proto-North American continent (Laurentia) in the Late Ordovician, causing an event called the Taconic Orogeny.

Scanning electron micrographs of “small shellies” from the limestone at Claverack, New York. Images originally from Ed Landing for the Museum of the Earth.

Early bivalve Fordilla troyensis

Early Cambrian rocks exposed near Troy, in Rensselaer County, New York, contain fossils of one of the earliest known bivalve mollusks (Fordilla troyensis). This mollusk was discovered in 1881.

The bivalve Fordilla troyensis from the Early Cambrian of Rensselaer Co., NY (PRI 50316). Photo by Vicky Wang.

Ordovician

Rocks in central New York contain two of the most famous Ordovician trilobite deposits in the world: the Trenton Group and Beecher's Trilobite Bed. Some of the oldest coral reefs known occur in the northwestern Vermont.

Trenton Group trilobites

Localities around Trenton Falls in Herkimer County, New York, have yielded many well-preserved trilobites and other fossils from the Middle Ordovician Rust Formation in the Trenton Group. This material formed the basis of one of the first descriptions of the two-branched legs of trilobites. The Trenton trilobites include Isotelus gigas, Ceraurus pleurexanthemus, and Nanillaenus americanus.

Isotelus gigas from the Ordovician Trenton Limestone of Trenton Falls, Oneida County, New York (PRI 104032).

Ceraurus pleurexanthemus from the Ordovician Rust Member of the Trenton Group, Walcott-Rust Quarry, Herkimer County, New York (PRI 42094).

Nanillaenus americanus from the Ordovician of Trenton Falls, Oneida County, New York (PRI 104021).

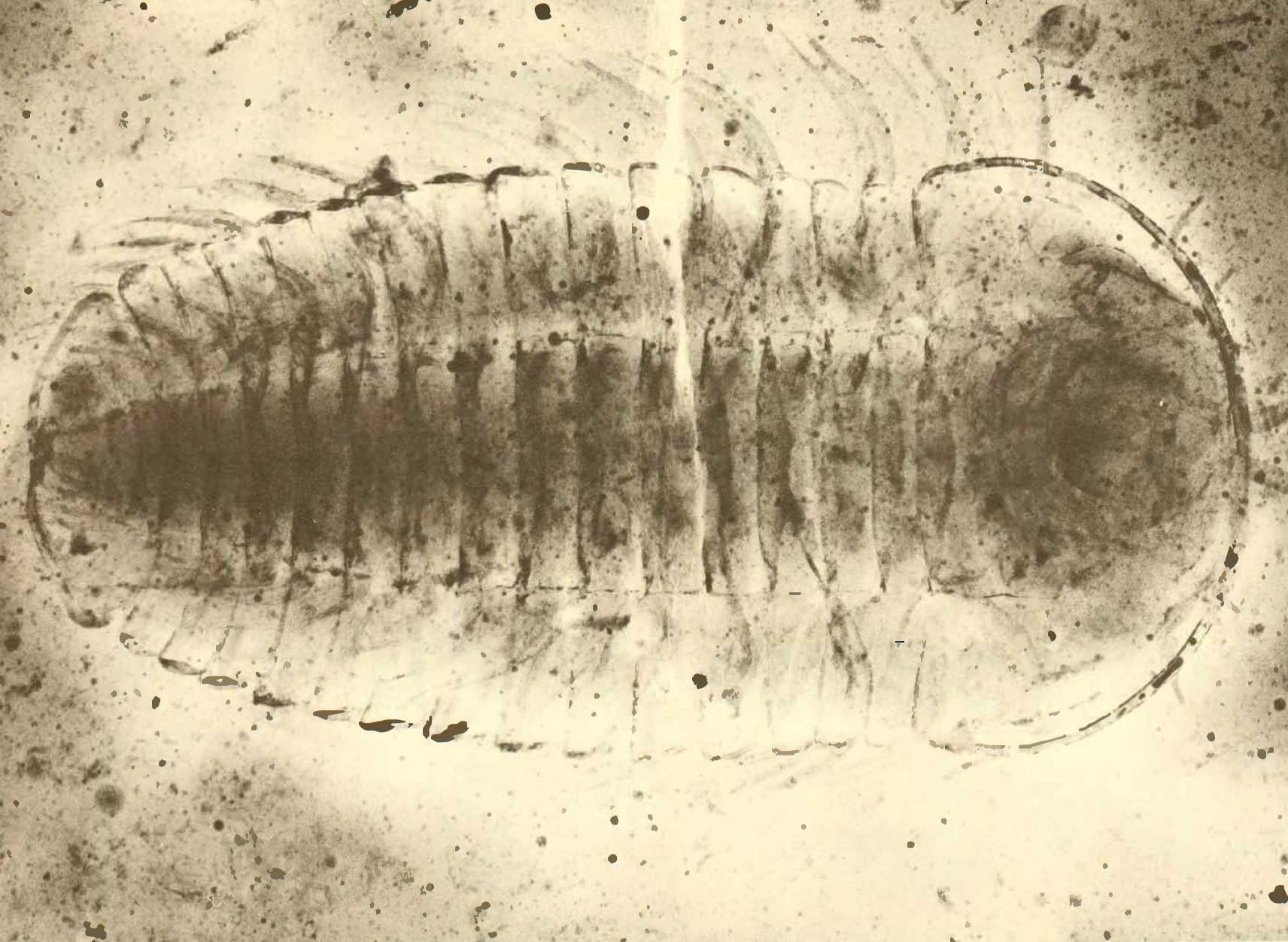

Beecher's Trilobite Bed

Beecher's Trilobite Bed is found in the Ordovician Frankfort Shale near Rome, Oneida County, New York. This bed, where is slightly younger than the Trenton Group, preserves an exceptional record of trilobites and other benthic macrofauna of a Late Ordovician deepwater marine environment.

Beecher's Trilobite Bed has long been famous for its extraordinary trilobites, which preserve the ventral appendages (the legs on the underside of the body) and even traces of the muscles. The exceptional fossils are preserved in iron pyrite, which allows their structure to be revealed using X-rays.

Triarthrus eatoni from the Ordovician Utica Shale of Herkimer County, New York (PRI 76772).

X-ray image from Triarthrus eatoni from Cisne (1981). Note preservation of legs on the left-side of the specimen (top of image).

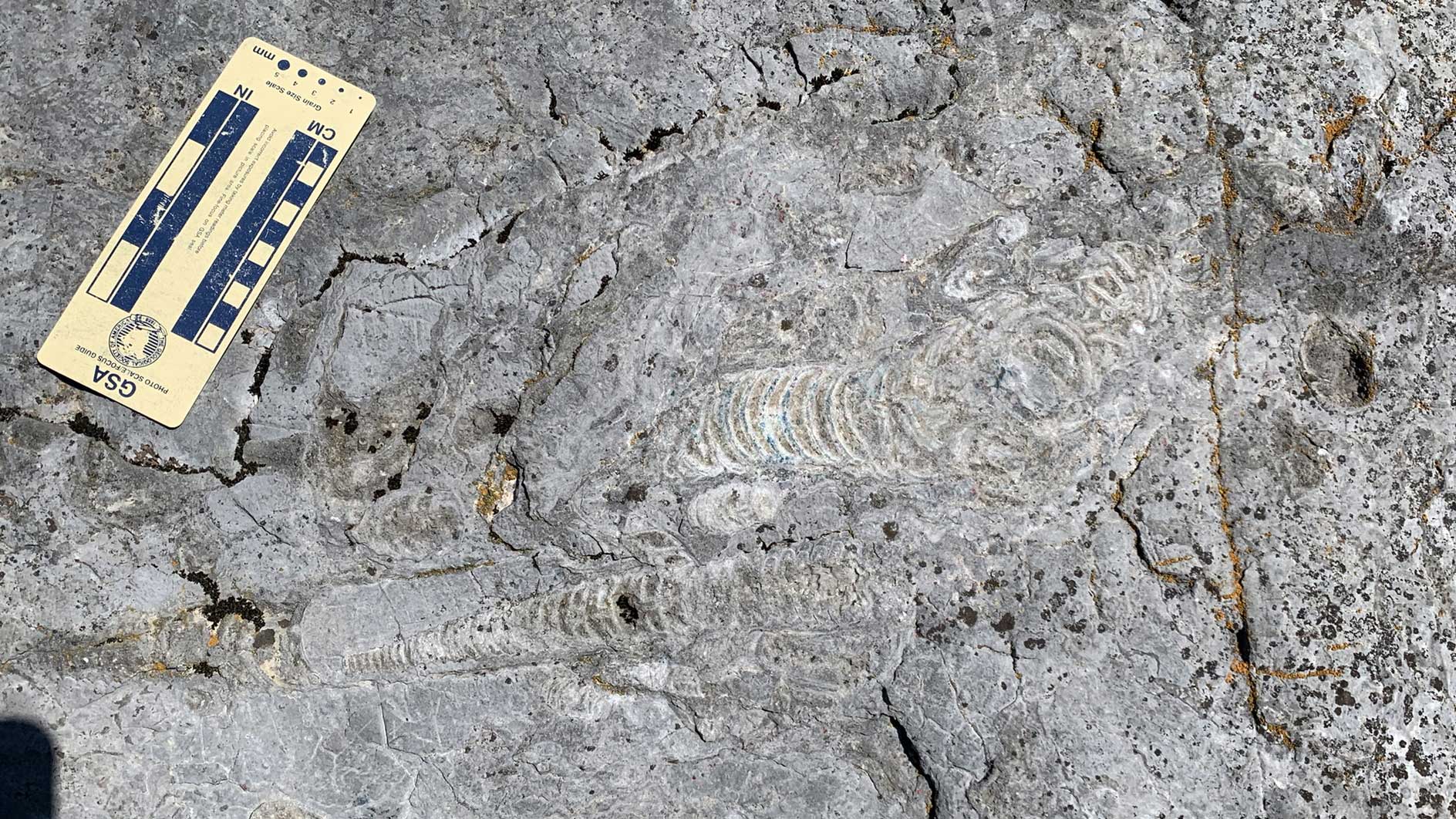

Chazy Reefs

The Middle Ordovician Chazy Formation of northwestern Vermont and northeastern New York contains beautiful exposures of what have been called “the world’s oldest coral reefs.” These buildups include not only corals but also stromatoporoids (large sponges), as well as marine animals like trilobites, gastropods (snails), and nautiloids (squid-like animals with shells). Some of the best exposures that are easily accessible to the public are on Isle La Motte, Vermont, the northernmost island in Lake Champlain.

Large stromatoporoid colony in the Chazy Formation at Isle La Motte in Vermont. Photographs by Warren D. Allmon.

Straight-shelled nautiloid fossils in the Chazy Formation of Vermont. Photograph by Warren D. Allmon.

Large gastropod fossil in the Chazy Formation of Vermont. Photograph by Warren D. Allmon.

Silurian

Rochester Shale

Outcrops of the middle Silurian (about 430 million-year-old) Lewiston Member of the Rochester Shale around the city of Lockport, Niagara County, New York, yield extraordinary fossils. This lagerstätte (exceptionally well-preserved fossil deposit) was created by storm events that stirred up clouds of sediment; these clouds of sediment then rolled across the shallow seafloor, smothering animals in their path. When the Rochester Shale was deposited, New York was in the southern subtropics, between 25°S and 30°S.

The Rochester Shale fossils first became famous during the excavation of the Erie Canal in the 1820s. The deposits were largely forgotten until the late 1970s, when localities around the town of Middleport began to produce abundant, beautifully preserved marine invertebrate fossils, including brachiopods, trilobites, and echinoderms.

Arctinurus boltoni from the Rochester Shale of Niagara County, New York on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York (PRI 11043).

Bertie Group

The Bertie Group (also known as the Bertie Limestone, Bertie Dolomite, Bertie Waterlime, or Bertie Formation) is an upper Silurian deposit in southern Ontario, Canada, and western New York State. The Silurian deposits were formed when Ontario and New York were at a low latitude position. The climate was warm and arid, which led to the formation of evaporite deposits that reach often hundreds of meters thick.

Two formations within the Bertie, the Fiddler's Green and Williamsville, are considered lagerstätten deposits (deposits with exceptionally preserved fossils) that contain a unique soft-bodied fauna. These formations are world-famous for their eurypterids (sea scorpions) and also contain nautiloids, xiphosurans (the group that includes horseshoe crabs), early land plants, and an early scorpion. The habitat of the eurypterids and the rest of the Bertie biota might still have been marginal marine, which would explain its low diversity and lack of “normal” marine fauna.

Complete specimen of Eurypteris remipes from the Silurian Bertie Limestone, Herkimer County, New York (PRI 70770).

Specimen of the giant eurypterid Acutiramus macrophthalmus on display at the Museum of the Earth (PRI 50266). Image modified from fig. 9 in Briggs and Roach (2020 in Geology Today).

Medina Sandstone

The red Medina Sandstone, which is exposed in Niagara Gorge near Buffalo and elsewhere across western New York, contains abundant marine trace fossils, including Arthrophycus.

Slab of Silurian Medina Sandstone containing the trace fossil Arthrophycus sp. (PRI 50258). Specimen is from Orleans County, New York, and is on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York.

Trace fossil (or, ichnofossil) specimen of Arthrophycus alleghaniensis from the Silurian Medina Sandstone of Orleans County, New York (PRI 76756). The animal that made these feeding traces may have been an arthropod. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Maximum dimension of specimen is approximately 12.5 cm.

Devonian

New York State and Pennsylvania have among the most important fossil records of Devonian life anywhere in the world, spanning marine to terrestrial ecosystems. A few highlights are presented below, but you are encouraged to explore the following links, which provide much more thorough introductions and overviews.

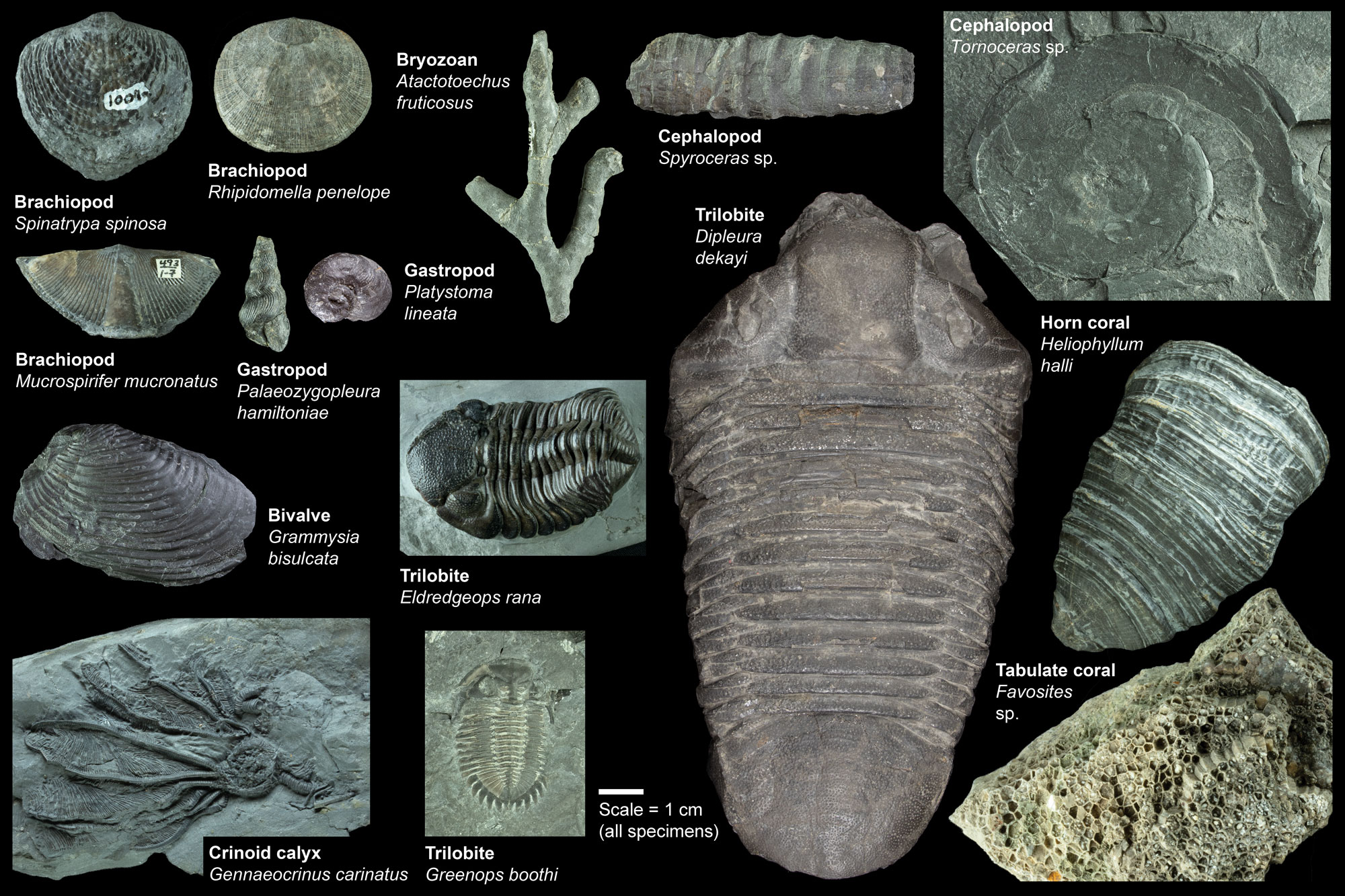

Examples of different types of marine invertebrate fossils that have been found in Devonian rocks in New York State. Specimens are from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Gilboa fossil forest

The Gilboa fossil forest was discovered in 1869 when workmen quarrying rock along Schoharie Creek discovered several fossilized tree stumps. These fossils caught the attention of New York State Paleontologist James Hall, who arranged for them to be taken to the State Museum in Albany. Construction of the Gilboa Dam on Schoharie Creek began in 1917. Dozens of additional stumps were discovered in nearby rock that was being quarried to construct the dam and salvaged before the quarry was closed and covered. The extinct trees represented by these fossil stumps are named Eospermatopteris.

Eospermatopteris stump, Glboa, Schoharie County, New York. Specimen is on permanent display in the Museum of the Earth (PRI 49876).

Catskills freshwater bivalves

Bivalves evolved in the ocean and did not move into freshwater until the Devonian. This may have happened because the expansion of land plants during the Devonian caused an increase in the amount of organic matter in fresh water, such as was flowing off of the young Appalachian Mountains across the Catskill Delta. This organic matter provided food for the bivalves.

Red sandstones of the Devonian Catskill Delta in eastern New York and eastern and central Pennsylvania preserve abundant large specimens of the world’s oldest known freshwater bivalves (Archanodon catskillensis). These are some of the oldest known freshwater bivalves in the world.

Archanodon catskillensis, East Windham, Greene County, New York. The lower surface of this slab contains bits of wood and fragments of leaves from some of these land plants. The bivalve shells themselves appear to be oriented in a single direction, perhaps caused by flowing water. On loan from Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, PA.

Montour Preserve

The Middle Devonian Mahantango Formation is exposed across north-central Pennsylvania and is publicly accessible at the Montour Preserve in Danville in Moutour County. The Mahantango Formation contains abundant bivalves, nautiloids, brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, gastropods, corals, and trilobites.

Slab of rock from the Mahantango Formation containing abundant marine invertebrate fossils, including bivalves and brachiopods. Photograph by John Brandauer (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Glass sponges

The glass sponges from the Devonian of New York are famous around the world. Fossil siliceous sponges also occur in Pennsylvania.

Fossil specimen of the glass sponge Uphantaenia chemungensis from the Devonian Enfield Formation of Tompkins County, New York (PRI 76745). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Maximum diameter of specimen (not including surrounding rock matrix) is approximately 11.5 cm.

Fossil specimen of the glass sponge Hydnoceras tuberosum from the Devonian of Steuben County, New York (PRI 76741). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 26 cm.

In 1939 paleontologist Kenneth Caster described sponges from the Devonian and Mississippian of western Pennsylvania. One of these, Titusvillia drakei, was named for the man (Col. Edwin Drake) who founded the modern oil industry in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in the mid-nineteenth century. The fossil sponge was unusual in being branched, which is a rare growth form in modern sponges. Similar sponges are also known in the Devonian of New York.

Branching sponge Titusvillia drakei (CMC IP22130). Photograph provided by Cameron Schwalbach, Cincinnati Museum Center, Ohio.

Carboniferous

Coal swamp plants

During the Carboniferous (and especially the Pennsylvanian), what is now the Interior Basin region of the Northeast was a broad, low coastal plain near the Equator. It was home to extensive swamp forests. These ancient ecosystems are sometimes called “coal swamps” because the stagnant, wet environments in which they thrived prevented large volumes of vegetation from decomposing. As the plant matter accumulated for tens of millions of years, it formed thick, extensive deposits of coal underlying parts of the Inland Basin.

Pennsylvania preserves one of the best-known Pennsylvanian-age plant communities in the world. Plant and other non-marine fossils from the Mississippian and the early Permian are also present in Pennsylvania, but are far less extensive. Pennsylvanian plants are also found in Maryland.

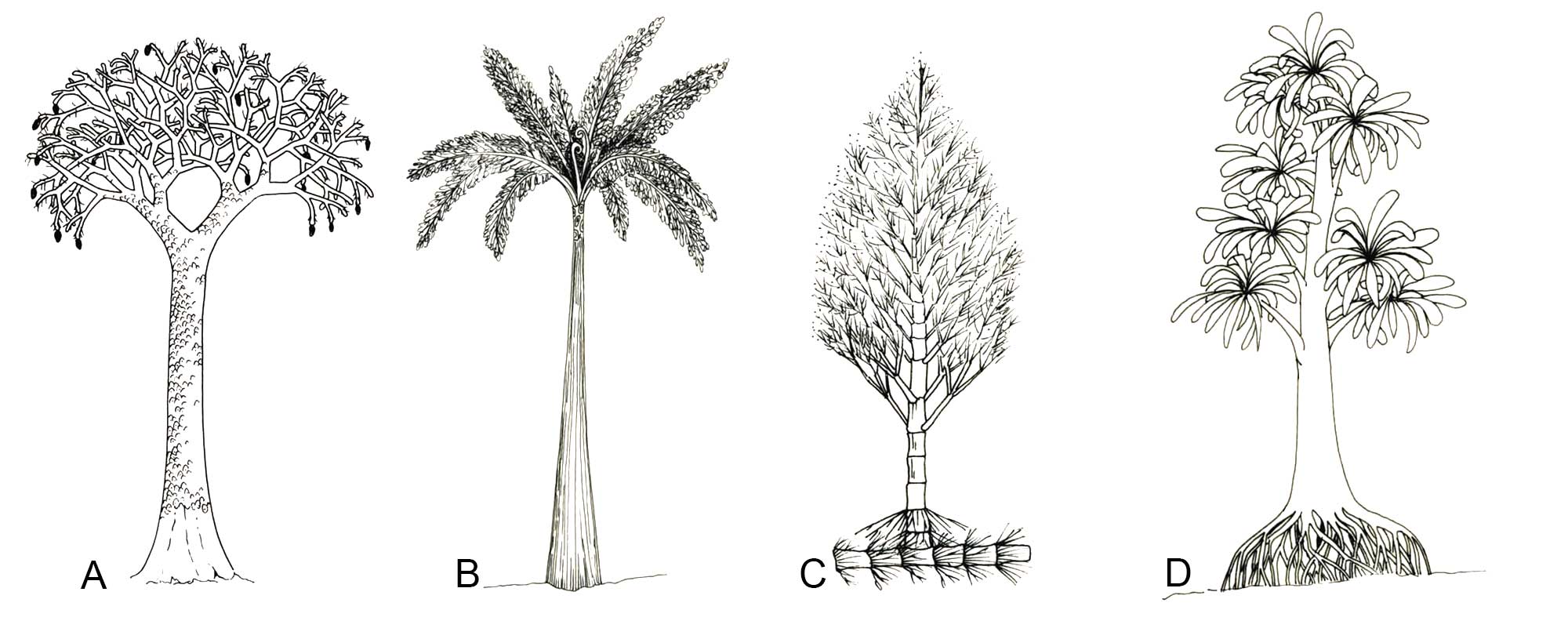

The trees found in these forests did not belong to the familiar groups that dominate modern forests, such as conifers and flowering broadleaf plants. Instead, these early forests were made up of groups of plants that are either extinct or much less conspicuous today. These groups were the lycophytes (club mosses and relatives), the sphenophytes (horsetails and relatives), the marattioid ferns, seed ferns (seed-producing plants with fern-like leaves), and the cordaites (a group related to conifers). Lycophytes and horsetails survive today, but often small, non-woody plants. Marattioid ferns are restricted to the tropics. Cordaites and seed ferns are extinct.

Restorations of Pennsylvanian coal swamp trees. A. Scale tree (Lepidodendron), a lycophyte that reached 30 m (100 ft) tall. B. Psaronius, a marattioid tree fern, reached 3 m (10 ft) tall. C. Calamites, a sphenophyte (horsetail), reached 20 m (65 ft) tall. D. Cordaites, a conifer-like seed plant; reached 10 m (35 ft) tall. Illustration by Christi Sobel.

Calamites

Pennsylvanian-age calmaites reached over 30 meters high. Their stems are known as Calamites and their leaves are called Annularia and Asterophyllites.

Fossil specimen of a stem base of the horsetail (Equisetophytes) Calamites suckowi from the Pennsylvanian of Pennsylvania (PRI 50479). Note the characteristic nodes (horizontal lines) and internodal ribs (vertical lines). Specimen is on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York. Length of fossil is approximately 21.5 cm.

Specimen of Asterophyllites from the Pennsylvanian Allegheny Formation, Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Asterophyllites is a type of foliage produced by an ancient relative of modern horsetails. Photo of YPM PB 000699 by Robert Swerling, Yale Peabody Museum, 2020 (CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Scale trees

Scale trees (lycophytes in the order Lepidodendrales) grew up to 45 meters high in Mississippian and Pennsylvanian forests. The root-like anchoring structures of these scale trees are called Stigmaria, whereas the stems are known by a variety of names depending on the form of the scale-like patterns on their surfaces.

Trunk of the lycopod Lepidodendron sp. from the Pennsylvanian of Sullivan County, Pennsylvania (PRI 49900). Specimen is on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York.

Seed ferns

Seed ferns (pteridosperms) lived from the Mississippian to the Cretaceous. The leaves of these plants resemble ferns but the plants produced seeds.

Leaves of the seed fern Neuropteris sp. from the Pennsylvanian of Sullivan County, Pennsylvania (PRI 50245).

Leaves of seed ferns from the Pennsylvanian of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania (PRI 50260).

Pleistocene

Terrestrial fossils

Cave fossils

Caves are an example in which the underlying geology, generally limestone, influences the Pleistocene record. Cave faunas are not terribly common in the Northeast, but are very important in some other areas of the country where caves are numerous. A Pleistocene cave formed from Devonian limestone in Allegheny County, Maryland, included a wide range of mammals representing both northern and southern climates, as well as those of more intermediate climates, suggesting a biogeographic transitional zone in which the climate had fluctuated.

Lake and pond fossils

Important and extensive freshwater and terrestrial remains occur in the innumerable pond sediments (not in the least lithified into rocks) left behind after retreat of the last glaciers. These ponds are well known from areas that were covered with ice and glacial sediment, especially kettles that formed along moraines and other ice-margin deposits. Since such pond sediments are not surface outcrops, and since there is no foolproof technology for searching for bones under the sediment, most skeletons turn up during construction or pond alteration rather than through systematic searches for remains.

One important Pleistocene deposit from the Inland Basin region of the Northeast is the Byron Dig Site or Hiscock Site in western New York. This site was discovered in 1959, when a pond was being dug on a farm. The site was first explored by scientists from the Buffalo Museum of Science shortly afterwards, who recovered bones of a mastodon. Decades later, in the 1980s, the site was revisited, and it became an excavation that lasted for decades. It yielded bones of mastodons, moose, carbou, and peccaries, among other animals, as well as human bones and archaeological artifacts crafted by humans.

Mastodon bones, Byron Dig (Hiscock Site), Genesee County, New York. Specimens on display at the Buffalo Museum of Science, New York. Photo by Daderot (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Marine fossils

One can visit places in the Northeast where sea level rise outpaced the rebounding continental crust after retreat of the glaciers, flooding lowlands such as areas of Massachusetts and along the St. Lawrence Seaway. The Champlain Sea refers to an ocean bay that filled most of the Ottawa-St. Lawrence-Lake Champlain basin about 11,000 to 8,000 years ago. The fossils from these sediments are so recent that most or all are represented by living populations today, but mostly in more northerly, cooler locations.

The most celebrated fossil from the Champlain Sea deposits has been the "Charlotte whale," a specimen of the modern beluga whale, found in Chittendon County, Vermont in 1849 by workers digging a railroad. Though initially shocked to find whale remains so far inland, it eventually became apparent that the whale had come down the St. Lawrence Seaway at a time that this area had been flooded with sea water. The Champlain Sea extended into New York, where a fossil beluga whale was also discovered in 1987. Other whale remains found have included the harbor porpoise, humpback whale, finback whale, and bowhead whale.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Daring to Dig: Carol Faul [Faul was involved in the initial excavation of the Byron Dig Site in the 1950s]: https://www.museumoftheearth.org/daring-to-dig/bio/faul

Daring to Dig: Winifred Goldring: https://www.museumoftheearth.org/daring-to-dig/bio/goldring

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Midwestern U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland (covers the Central Lowland in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-cl/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Midwestern U.S.: Fossils of the Inland Basin (covers the Central Lowland in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio): https://earthathome.org/hoe/mw/fossils-ib

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland (covers the Central Lowland in Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-cl/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland and Interior Highland (covers the Central Lowland in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-cl-ih/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Inland Basin (covers the Inland Basin in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia): https://earthathome.org/hoe/se/fossils-ib

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/

Museum of the Earth: NY Rocks! Ancient Life of the Empire State: https://www.museumoftheearth.org/ny-rocks