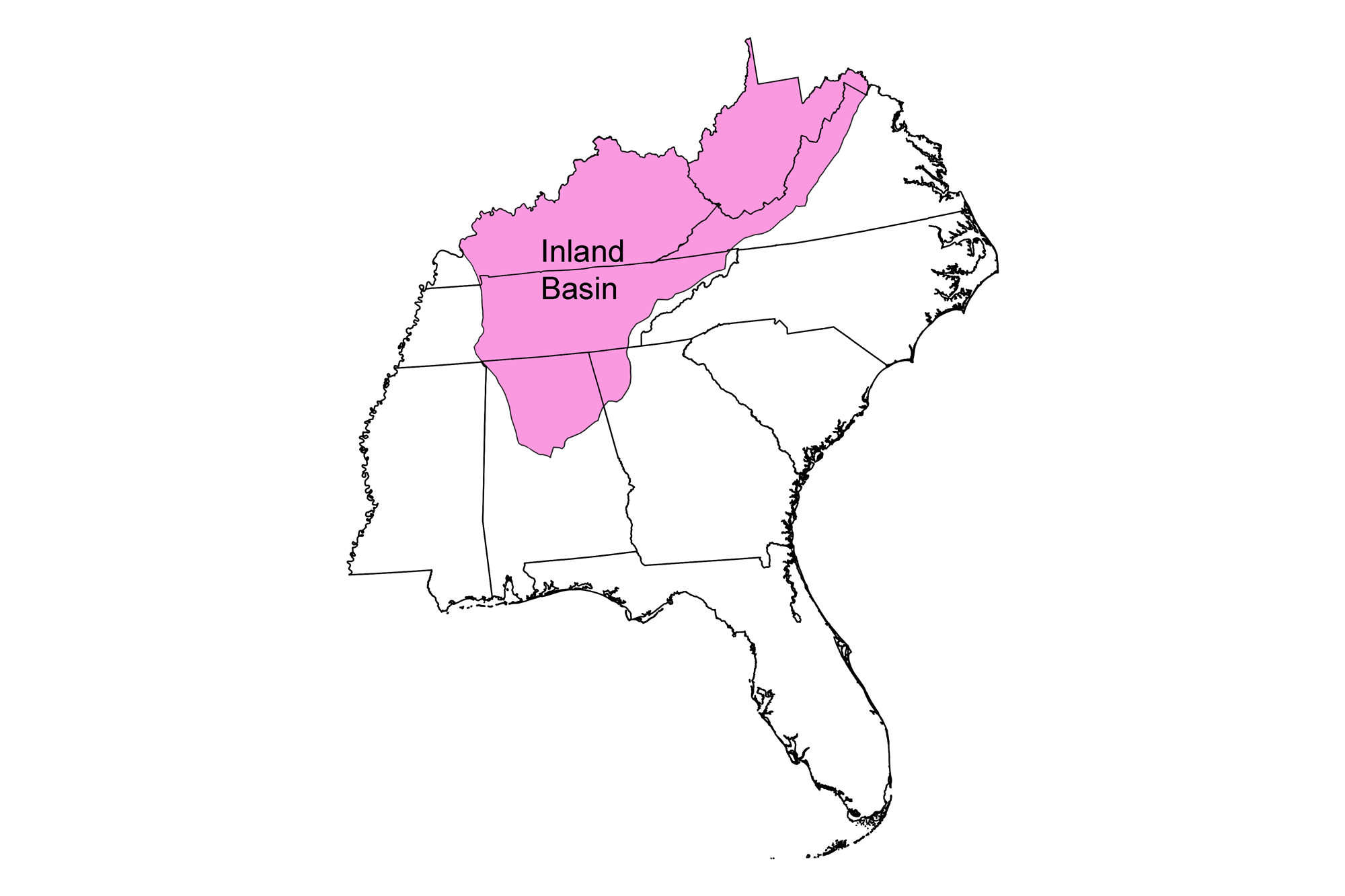

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Inland Basin region of the southeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Paleozoic marine invertebrates; Paleozoic sharks and bony fishes; Paleozoic terrestrial fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Cenozoic terrestrial fossils; Gray Fossil Site (Tennessee); Big Bone Lick State Park (Kentucky); Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Fossils of the Southeastern US" by Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S., 2nd ed., edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 25, 2023.

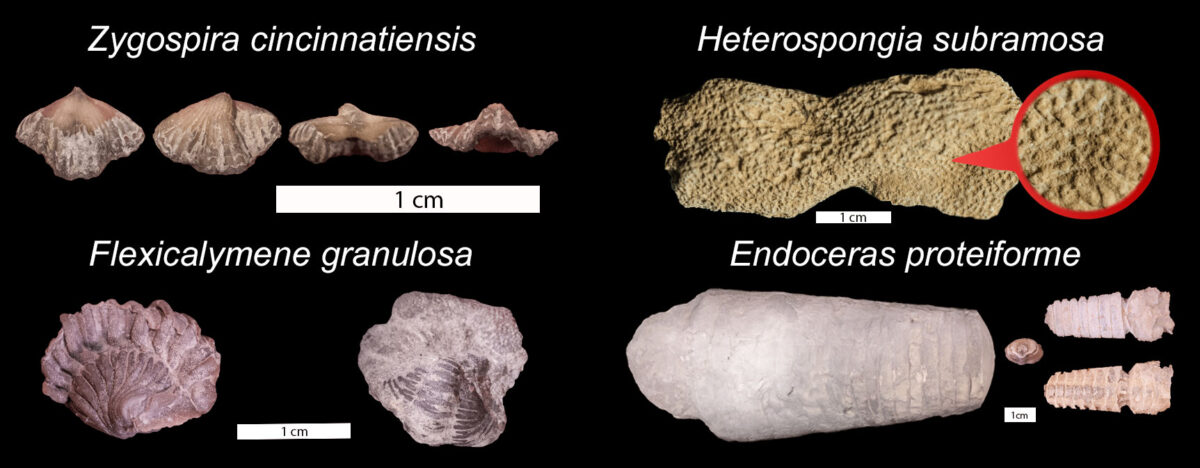

Image above: Ordovician fossils from Kentucky. Top left: A brachiopod (Zygospira cincinnatiensis), Eden Formation, in four views. Top right: A sponge (Heterospongiasubramosa), Richmond Formation. Bottom left: A trilobite (Flexicalymene granulosa), Kope Formation. Bottom right: A cephalopod (Endoceras proteiforme), Kenton Formation. All images from the Atlas of Ordovician Life.

Paleozoic fossils

Paleozoic marine fossils

Marine invertebrates

The Inland Basin region primarily contains the story of Paleozoic mountain-building events, associated sediment deposited in the inland sea, and changes in relative sea level, superimposed on the evolution of Paleozoic marine and coastal plant life.

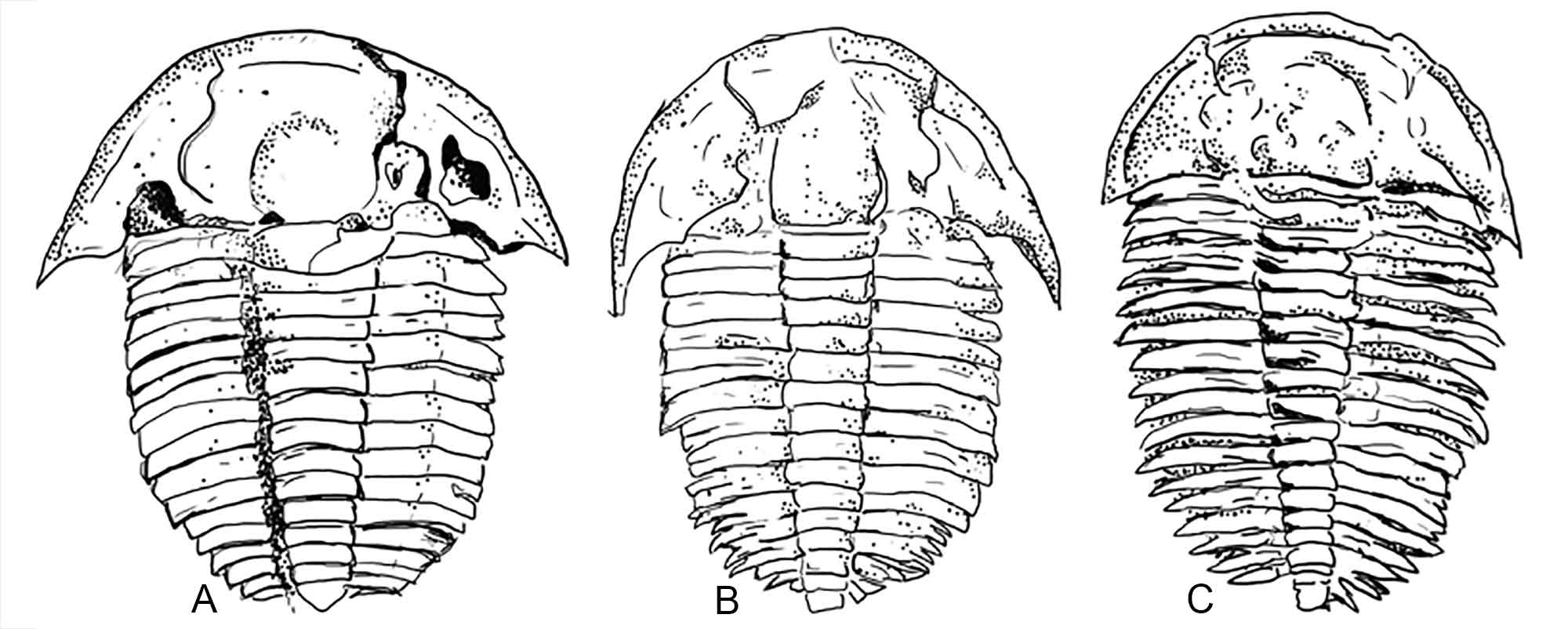

Exposures of Cambrian rocks with fossils are uncommon in this region, but a few can still be found. The early Cambrian Antietam Sandstone of West Virginia and Virginia contains Skolithos trace fossils (see below), as well as occasional trilobites and brachiopods. Early Cambrian fossils, especially trilobites, are also found in western Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and northwestern Georgia. In eastern Tennessee (near Knoxville), trilobite trace fossils called Rusophycus and Cruziana are common in Cambrian rocks that appear to have been deposited in intertidal environments.

Cambrian trilobites from northwestern Georgia and northeastern Alabama. A. Elrathia antiquata, approximately 2 centimeters (0.8 inches) long. B. Aphelaspis brachyphasis, approximately 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) long. C. Modocia sp., approximately 2 centimeters (0.8 inches) long. Drawings by Alana McGillis.

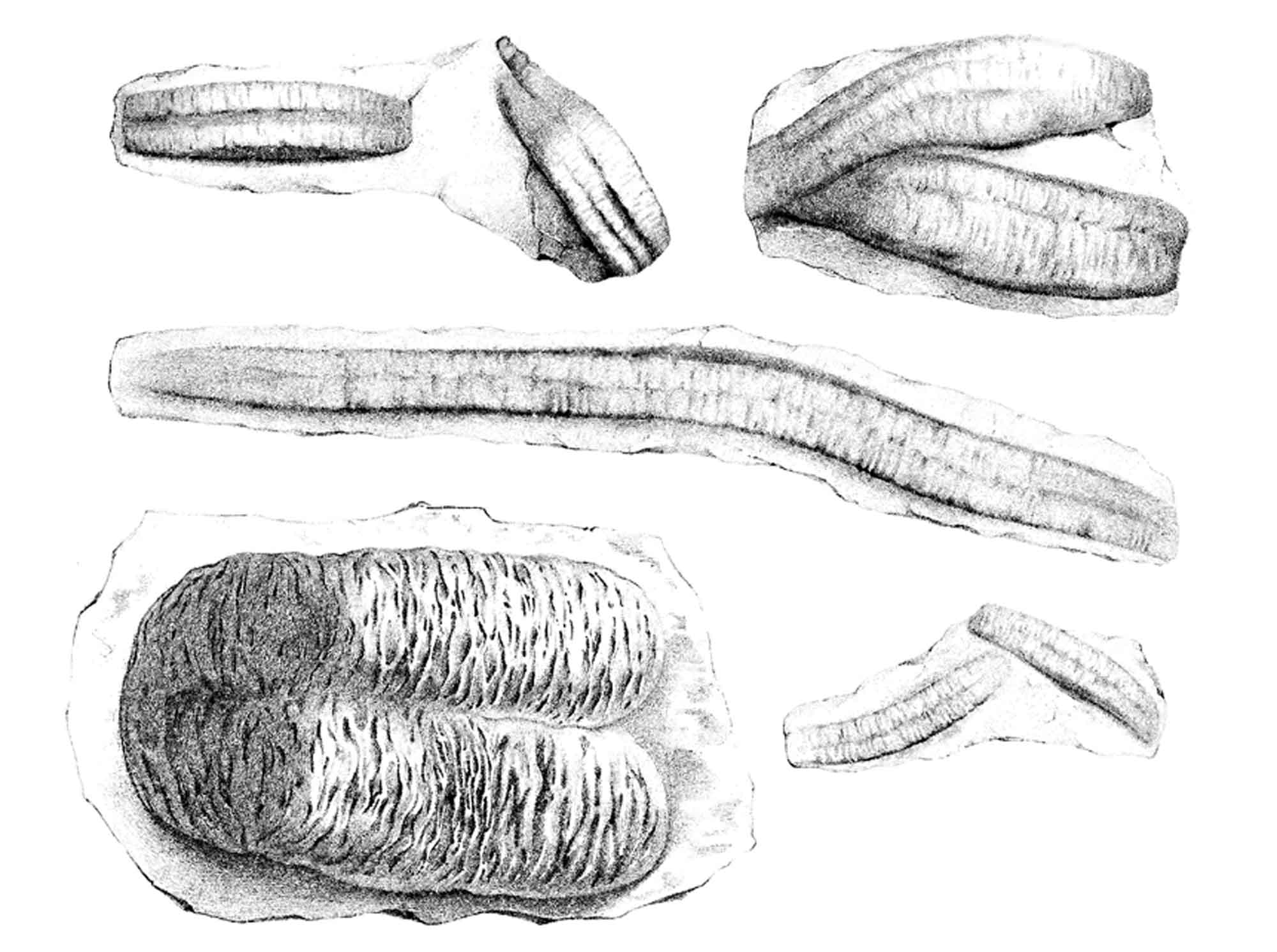

Trace fossils commonly associated with trilobites. Rusophycus are resting traces, recording the outline of the organism while it remains still. Cruziana are elongate, bilaterally symmetrical paths with repeated striations, recording the animal’s movement through the mud. Drawing by F.J. Swinton/lithograph by R.H. Pease, from plate 8 in J. Hall (1852) Palaeontology of New York, vol. 2 (public domain).

Trace fossil specimen of Rusophycus bilobatus from the Silurian Rose Hill Shale of Scott County, Virginia (PRI 76852). This resting trace was likely made by a trilobite. Specimen is from the research collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of rock is approximately 9.5 cm (Sketchfab; Creative Commons 0 license).

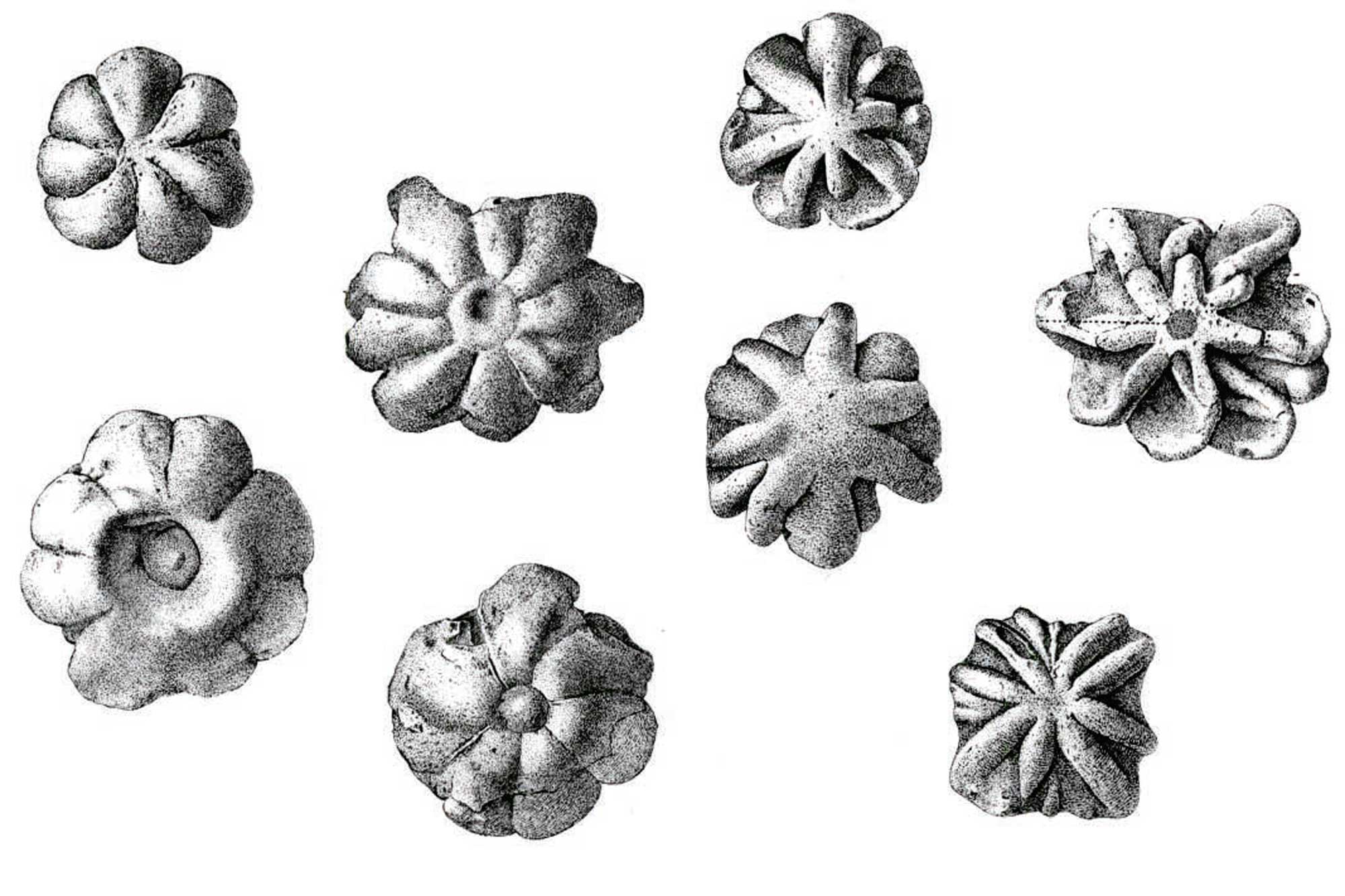

Shales and concretions in the middle Cambrian Conasauga Formation of northeastern Alabama and northwestern Georgia contain body and trace fossils that preserve the record of diverse soft-bodied organisms. There are also many mineralized skeletons. Fossils include algae, sponges, arthropods, brachiopods, echinoderms, mollusks, and trace fossils. Some of the most curious Conasauga fossils are Brooksella, also called "star cobbles." These enigmatic fossils have been thought of as medusae (jellyfish), algae, trace fossils, or inorganic structures. Recent research suggests, however, that they are most likely sponges with siliceous (SiO2) skeletons.

"Star cobbles" (Brooksella) from the Cambrian Conasauga Formation. Fossils are 2.5–5 centimeters (1–2 inches) across. Images from plate I in Walcott (1898) Monographs of the U.S.G.S, 30 (public domain).

Two views of a "star cobble" (Brooksella cambria) from the Cambrian Conasauga Formation, Coosa Valley, Alabama. This specimen has been repaired. The scales are in millimeters (10 millimeters = 1 centimeter = 0.4 inches). Photo of YPM IP 014351 by Krista Carlson, 2007 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian marine fossils are widespread in the Inland Basin and are typically abundant, diverse, and beautifully preserved. These fossil assemblages are nearly always dominated by brachiopods, but also contain trilobites, graptolites, corals, clams, crinoids, Skolithos trace fossils, and many others.

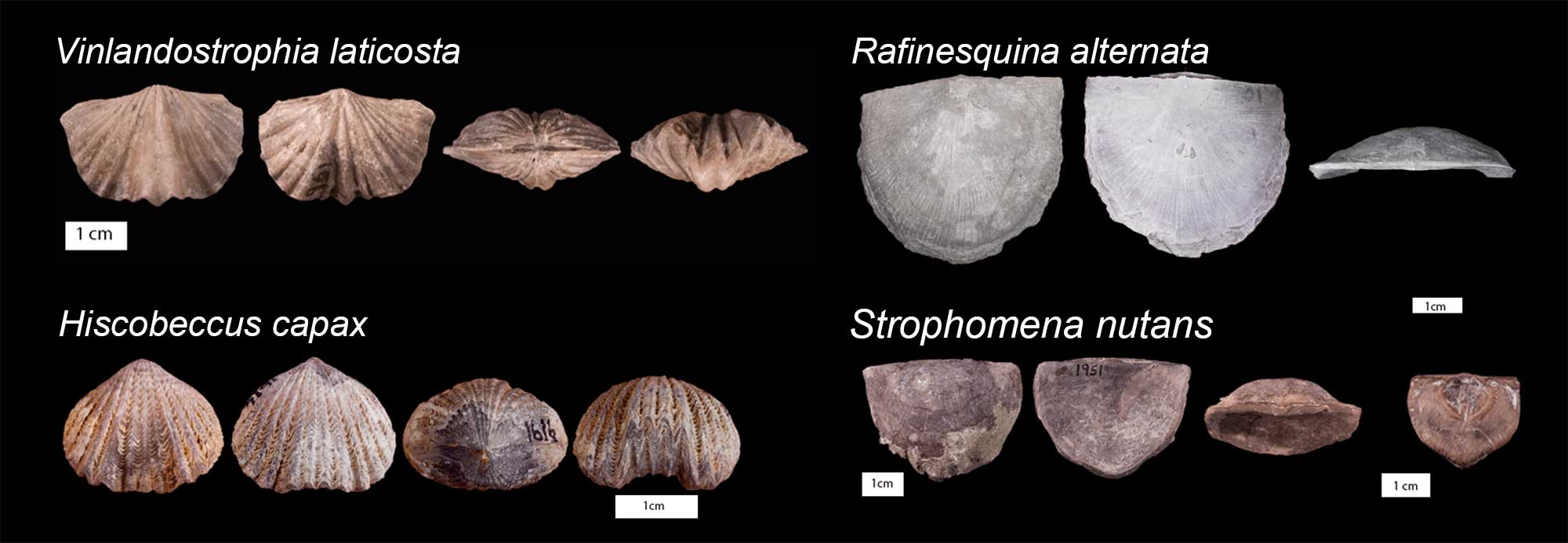

Examples of Ordovician brachiopods from the Cincinnati region, which includes northern Kentucky. Featured species include Vinlandstrophia laticosta (McMillan Formation of Crestview Hills, KY), Rafinesquina alternata, (Arnheim formation of Franklin County, IN), Hiscobeccus capax (Waynesville formation of Franklin County, IN), Strophomena nutans (Whitewater Formation of Maysville, KY). Images are from the Ordovician Atlas.

Slab of trilobites (Homotelus sp.) from the Ordovician of Virginia, approximately 38 centimeters (15 inches) across (PRI 40023; photograph by Wade Greenberg-Brand).

Middle Ordovician limestones in Tennessee are well known for containing numerous crinoids and fossils of the large gastropod Maclurites.

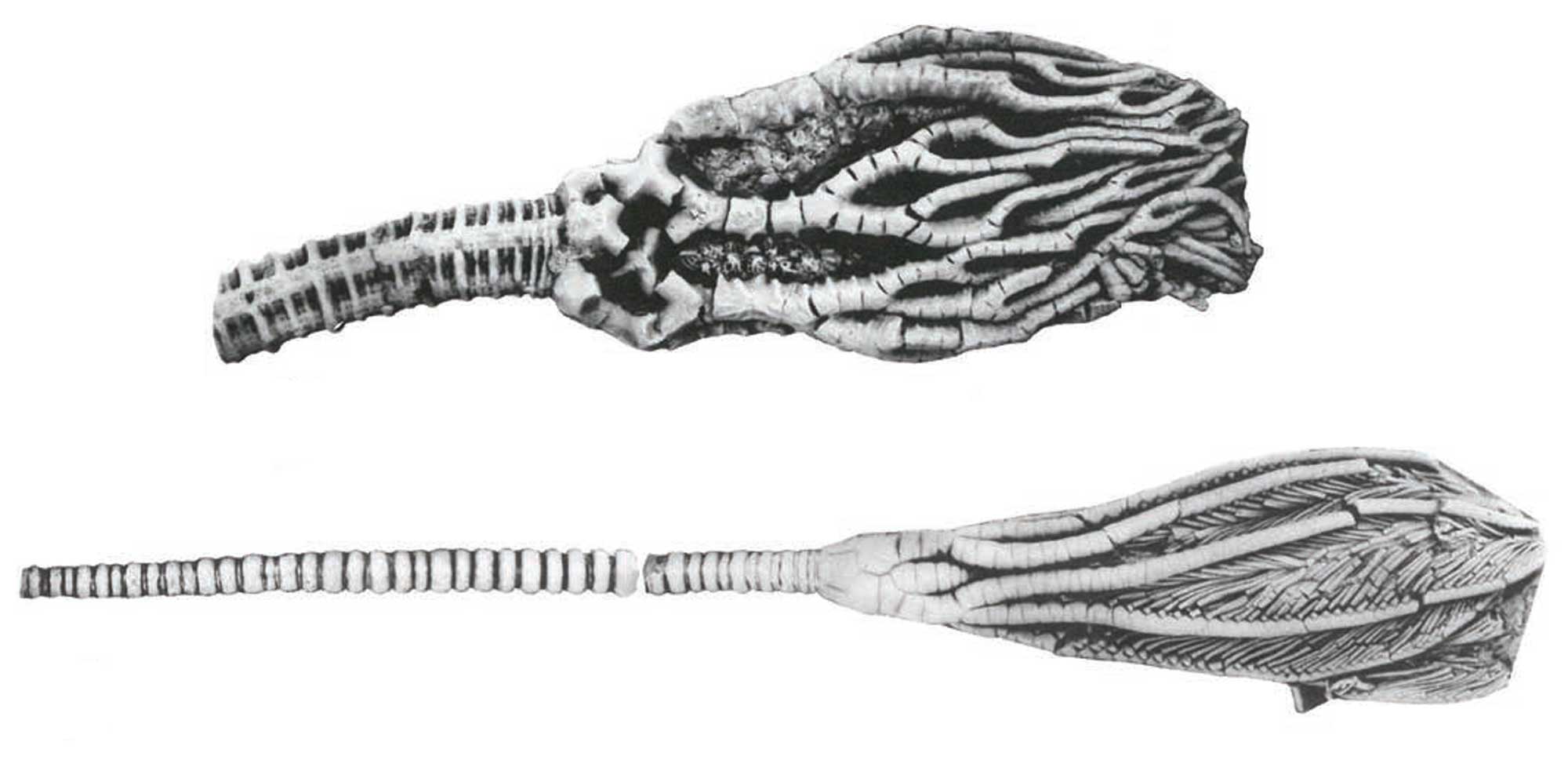

Crinoid calyces with arms and stem from the Ordovician Lebanon Limestone of Central Tennessee. Top: Reteocrinus alveolatus, approximately 6 centimeters (2.4 inches) long. Bottom: Cremacrinus sp., approximately 16 centimeters (6.3 inches) long. Images from Guensburg (1984) in Bulletins of American Paleontology; copyright Paleontological Research Institution.

Fossil snail (Maclurites bigsbyi) from the Ordovician Carters Limestone of Wilson County, Tennessee. Photos of YPM IP 025003 by Jessica Utrup, 2021 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

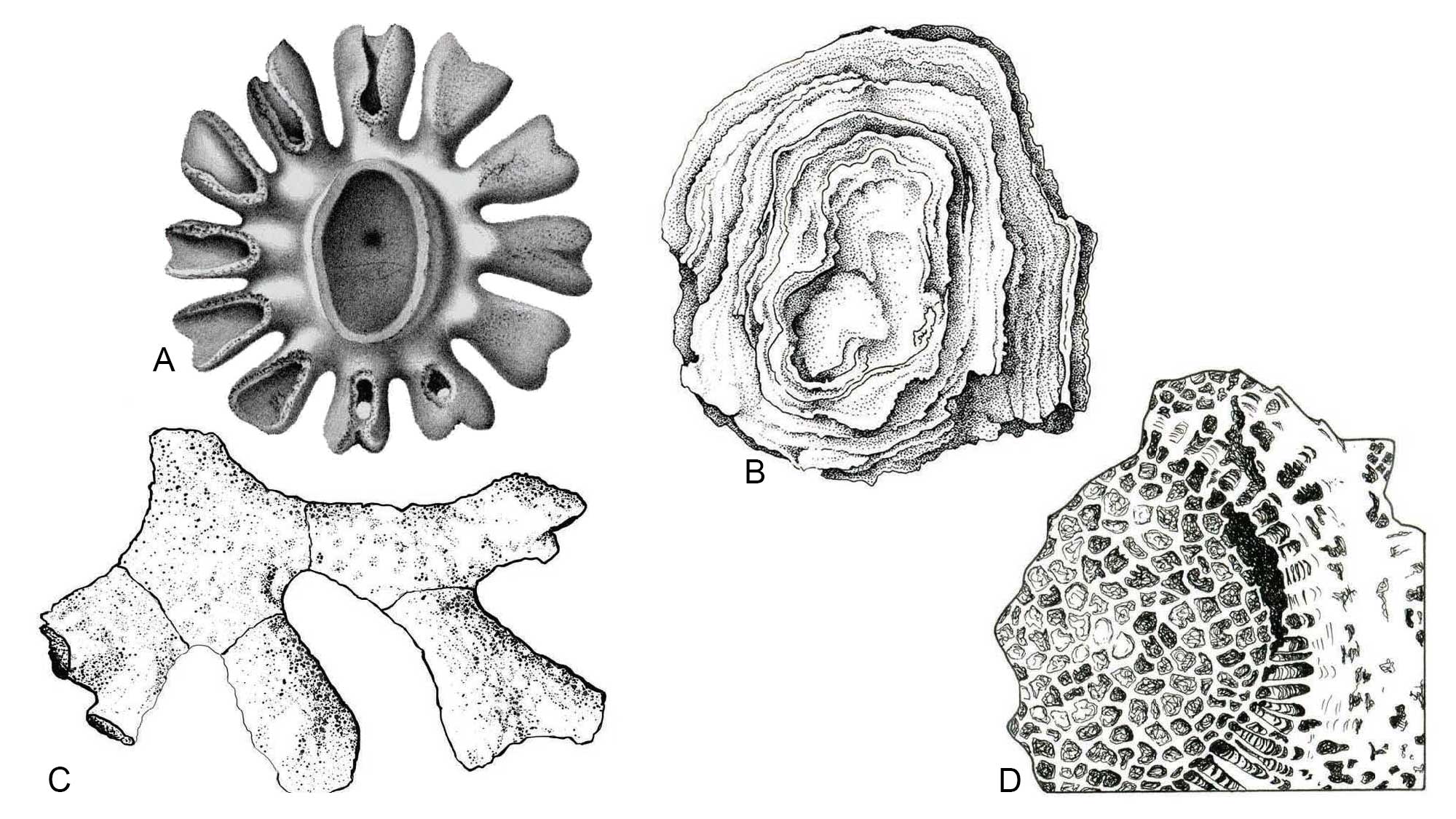

In Kentucky and Tennessee, trilobites, brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and the distinctive sponge Brachiospongia are also found in Ordovician rocks.

Common Ordovician reef-building organisms of the Interior Basin. A. Sponge (Brachiospongia digitata) approximately 25 cm (10 in) wide. B. Stromatoporoid sponge, approximately 30 cm (12 in) across. C. Bryozoan (Dekayia aspera) approximately 1 inch (2.54 centimeters) across. D. Tabulate coral (Favistella sp.) approximately 8 cm (3.2 in) wide. Image credits: A, Nettleroth (1889; Kentucky Fossil Shells: a Monograph of the Fossil Shells of the Silurian and Devonian Rocks of Kentucky, Kentucky Geological Survey, 245 pp., 36 pls.), public domain; B and D, copyright Christi Sobel; C, Alana McGillis.

Fossil sponge (Brachiospongia digitata) from the Ordovician of Franklin County, Kentucky (PRI 49856). Specimen is on public display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 23 cm (Sketchfab, Creative Commons 0 license).

Late Ordovician fossils are abundant in central Tennessee (around Nashville), central Kentucky (southeast of Louisville), and northern Kentucky. Ordovician limestones in the area around Strasburg, Virginia, contain abundant trilobites. The fossils are preserved as silica (SiO₂), and can therefore be extracted from the surrounding carbonate rock by treating it with dilute acid. This allows for the examination of delicate fossils that would otherwise be impossible to study.

In Alabama, the Silurian Red Mountain Formation, which is rich in the iron mineral hematite, contains reefs made largely of stromatoporoid sponges. Skolithos traces can be found throughout Silurian deposits in Tennessee, while Silurian deposits in Virginia contain abundant corals and brachiopods.

Skolithos burrows from the lower Silurian Clinch Formation at Clinch Mountain, Tennessee. Rocks with abundant Skolithos are sometimes called "pipe rock." The organism that made these burrows is unknown, but their shape suggests a worm-like creature that lived in the vertical burrows. Rock containing burrows is approximately 15 x 30 cm (6 x 12 in). Photograph by James St. John (flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Early to middle Devonian marine fossils are spectacularly exposed in the 390-million-year-old rocks at Falls of the Ohio in northern Kentucky. These beds of limestone are among the largest naturally exposed Devonian fossil deposits in the world. They are packed with the skeletal remains of countless corals, stromatoporoid sponges, echinoderms, brachiopods, mollusks, arthropods, and microscopic organisms. Well-preserved Devonian marine invertebrate fossils also occur in Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia.

The Mississippian is sometimes referred to as the "age of crinoids" because crinoids were so abundant that entire rocks are made up of bits of their calcite skeletons. Mississippian limestones from West Virginia to Alabama contain numerous fossils, including corals, gastropods, bivalves, bryozoans, blastoids, and fossilized shark teeth. West Virginia’s official state "gemstone" is Lithostrotionella, a Mississippian fossil coral from the Hillsdale Limestone found in portions of Greenbrier and Pocahontas counties. Carboniferous trilobites have also been found in northwestern Georgia and northern West Virginia.

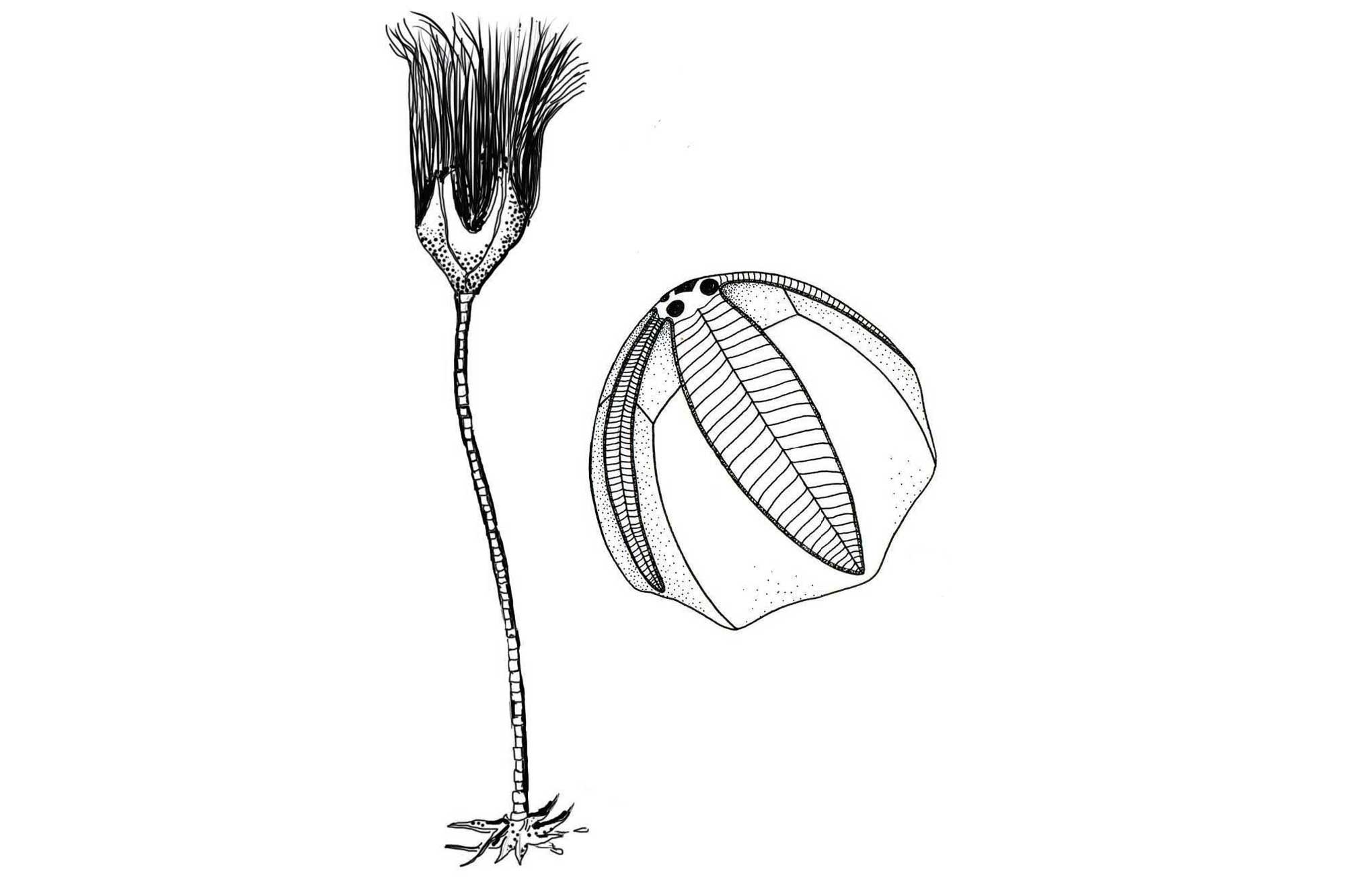

Blastoid (Pentremites sp.). Blastoids were a group of stalked echinoderms similar to crinoids. The calyx of a blastoid did not have long arms, but instead a series of holes called brachioles that held much shorter arms. Left: Restoration, approximately 15 centimeters (6 inches) tall. Right: Calyx. Image credits: Left, image by Alana McGillis, from image by Illinois State Geological Survey; Right, copyright Christi Sobel.

Calyx of a blastoid (Nucleocrinus cucullatus, two end views and side view) from the Devonian Jefferson Limestone of Jefferson County, Kentucky. Photo of YPM IP 082114 by Jessica Utrup, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Gilbertsocrinus typus, a crinoid from the Mississippian Borden Formation of north-central Kentucky, 8.5 cm (3.4 in). Photograph by Tim Evanson (flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

Sharks and body fishes

Sharks and bony fishes evolved rapidly during the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, and their fossils can sometimes be found in the rocks of the Inland Basin. Fossils of heavily armored bony fishes called placoderms are found in Kentucky and Tennessee, including the enormous Dunkleosteus.

Cast of a Dunkleosteus skull on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York.

Sharks first appeared in the late Silurian period, and their teeth are also preserved in these rocks. Among these are the bizarre and puzzling coiled tooth whorls of edestid sharks. These are sometimes found in shales overlying coal seams, indicating that the sharks inhabited shallow waters near shore.

Paleozoic terrestrial fossils

The oldest known fossils of land plants are isolated spores dating to the Ordovician Period. By the late Silurian, fossils of simple, leafless stems just a few centimeters tall are found in sediments that accumulated in low, wet, coastal environments. The first trees date to the early part of the Devonian period, and the first seeds to the middle Devonian. Devonian plant fossils are found in northeastern Alabama (Cherokee County). By the end of the Devonian, extensive forests containing many different kinds of trees and other plants had developed.

During the Mississippian and especially the Pennsylvanian, what is now the Interior Basin region of the Southeast was a broad, low coastal plain near the Equator. It was home to extensive swamp forests. The swamp forests that grew on Carboniferous coastal plains west of the Appalachian Mountains were dominated by four major groups of plants, each of which had independently evolved tree-like forms. These trees were tall plants held erect by a single stem made of stiff tissue; most produced wood.

The trees found in these forests did not belong to the familiar groups that dominate modern forests, such as conifers and flowering broadleaf plants. Instead, these early forests were made up of groups of plants that are either extinct or much less conspicuous today. These groups were the lycophytes (club mosses and relatives), the sphenophytes (horsetails and relatives), the marattioid ferns, seed ferns (seed-producing plants with fern-like leaves), and the cordaites (a group related to conifers). Lycophytes and horsetails survive today, but often small, non-woody plants. Marattioid ferns are restricted to the tropics. Cordaites are extinct.

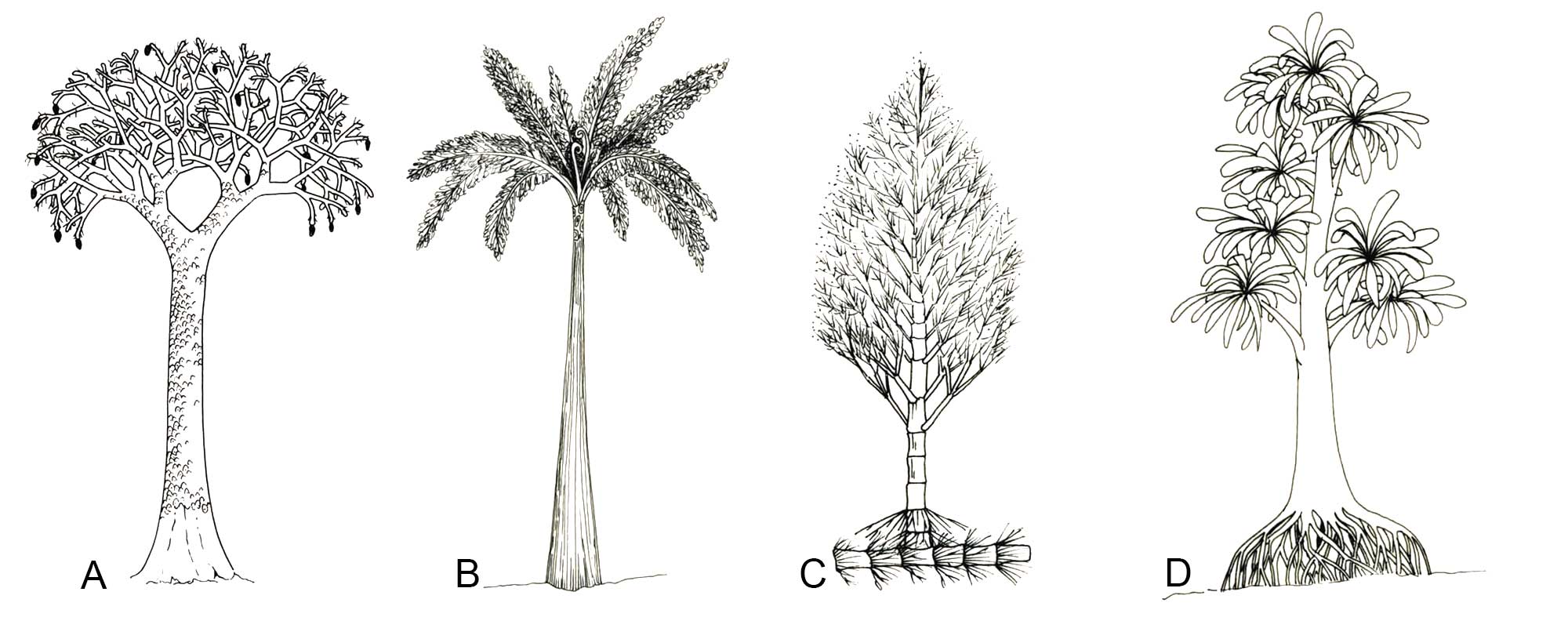

Restorations of Pennsylvanian coal swamp trees. A. Scale tree (Lepidodendron), a lycophyte that reached 30 m (100 ft) tall. B. Psaronius, a marattioid tree fern, reached 3 m (10 ft) tall. C. Calamites, a sphenophyte (horsetail), reached 20 m (65 ft) tall. D. Cordaites, a conifer-like seed plant; reached 10 m (35 ft) tall. Illustration by Christi Sobel.

Fossil specimen of the lycopophyte fossil Stigmaria from the Carboniferous of Morgan County, Tennessee (PRI 50355). Stigmaria is a rhizomorph, or root-like anchoring structure for ancient lycophyte trees. Note the helically arranged, circular rootlet scars. Specimen is on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 26.5 cm. Model by Emily Hauf (Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal, public domain dedication).

Fossil sphenophytes from the Carboniferous, near Careysville, Tennessee. Left: Portion of a Calamites stem (YPM PB 173150). Note the vertical ridges and furrows and horizontal joints that are characteristic of horsetails. Right: Whorls of Annularia leaves (YPM PB 173144) on a branch. Photos by Katie Grosh, 2020 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

Portion of the frond (fern-like leaf) of a seed fern, Alethopteris serlii, from the Pennsylvanian (late Carboniferous), Peach Tree Gap, Tennessee. Photo of YPM PB 029604 by Linda S. Klise, 2009 (YPM/Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility/GBIF.org).

The Carboniferous coal swamps were also home to a great diversity of animals, including insects, amphibians, and early reptiles. Although fossil bones have been found in Mississippian and Pennsylvanian rocks in West Virginia, Virginia, and Alabama, trace fossils are more common. One particular trackway site in Walker County, Alabama is one of the largest known Carboniferous track sites in the world (learn more).

Cenozoic

Cenozoic Terrestrial Fossils

The Interior Basin contains no fossil-bearing outcrops of Mesozoic age. It does, however, have a rich fossil record from the Neogene, including numerous sites at which Pleistocene and older terrestrial vertebrates have been found.

Spotlight: Gray Fossil Site, Tennessee

Gray Fossil Site is located near the small town of Gray in Washington County, northeastern Tennessee. It was discovered in 2000, when a road project unearthed fossil bones in a thick bed of clay that had accumulated in a flooded sinkhole. Subsequent excavation revealed the bones of numerous species of mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. The particular species present constrain the age of the fossil-bearing sinkhole deposit to the early Pliocene.

The fossils recovered from the site are noteworthy for several reasons. The site is an isolated Neogene deposit in the Appalachian region, and thus provides some of the only direct evidence for the types of animals and plants that lived there during the Neogene. It is also the world’s largest fossil tapir find, and it has yielded the most complete skeleton of Teleoceras (an ancient rhinoceros) found in eastern North America. A species of red panda from Gray Fossil Site is only the second (and most complete) record of this group in North America. Other fossil mammals present at Gray Fossil Site include salamanders, turtles, beaded lizards, alligators, shrews, moles, rabbits, rodents, weasels, short-faced bears, saber-toothed cats, mastodonts, camels, peccaries, ground sloths, and three-toed horses.

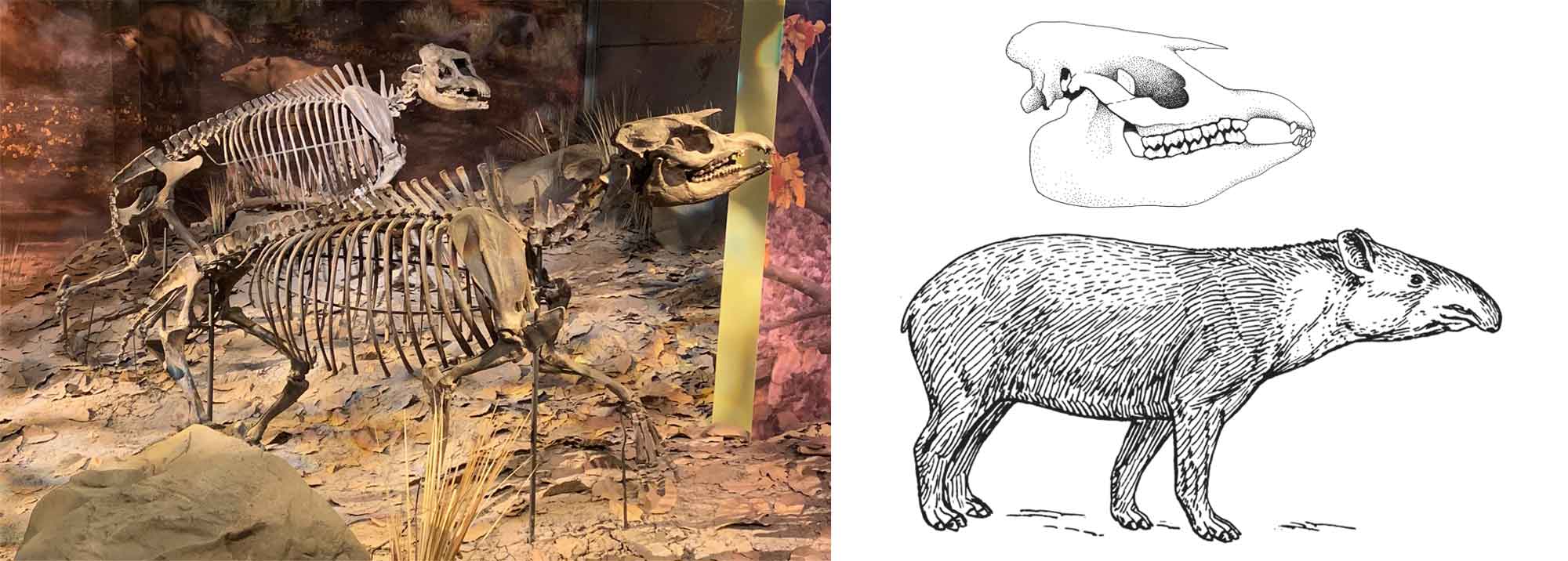

Ancient tapirs (Tapirus polkensis). Left: Specimen found at Gray Fossil Site, Tennessee, on display in the museum at the site (photograph by Elizabeth J. Hermsen). Right: Reconstructions of the skull and complete animal (skull drawing by Christi Sobel; animal drawing by Pearson Scott Foresman).

The ancient rhinoceros Teleoceras. Left: Specimen found at Gray Fossil Site, Tennessee, on display in the museum at the site (photograph by Elizabeth J. Hermsen). Right: Reconstructions of the skull and complete animal (skull drawing by Christi Sobel; animal drawing by Pearson Scott Foresman).

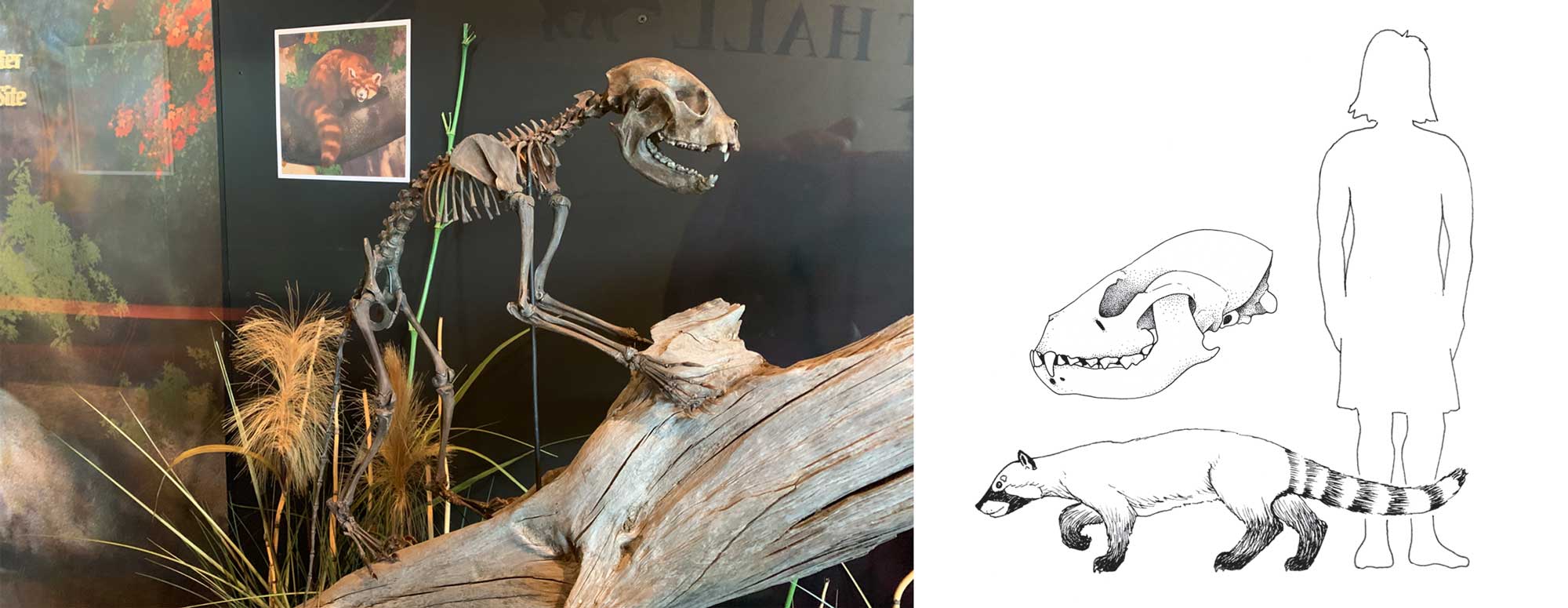

The red panda Pristinailurus bristoli. Left: Specimen found at Gray Fossil Site, Tennessee, on display in the museum at the site (photograph by Elizabeth J. Hermsen). Right: Reconstructions of the skull and complete animal; drawings by Christi Sobel.

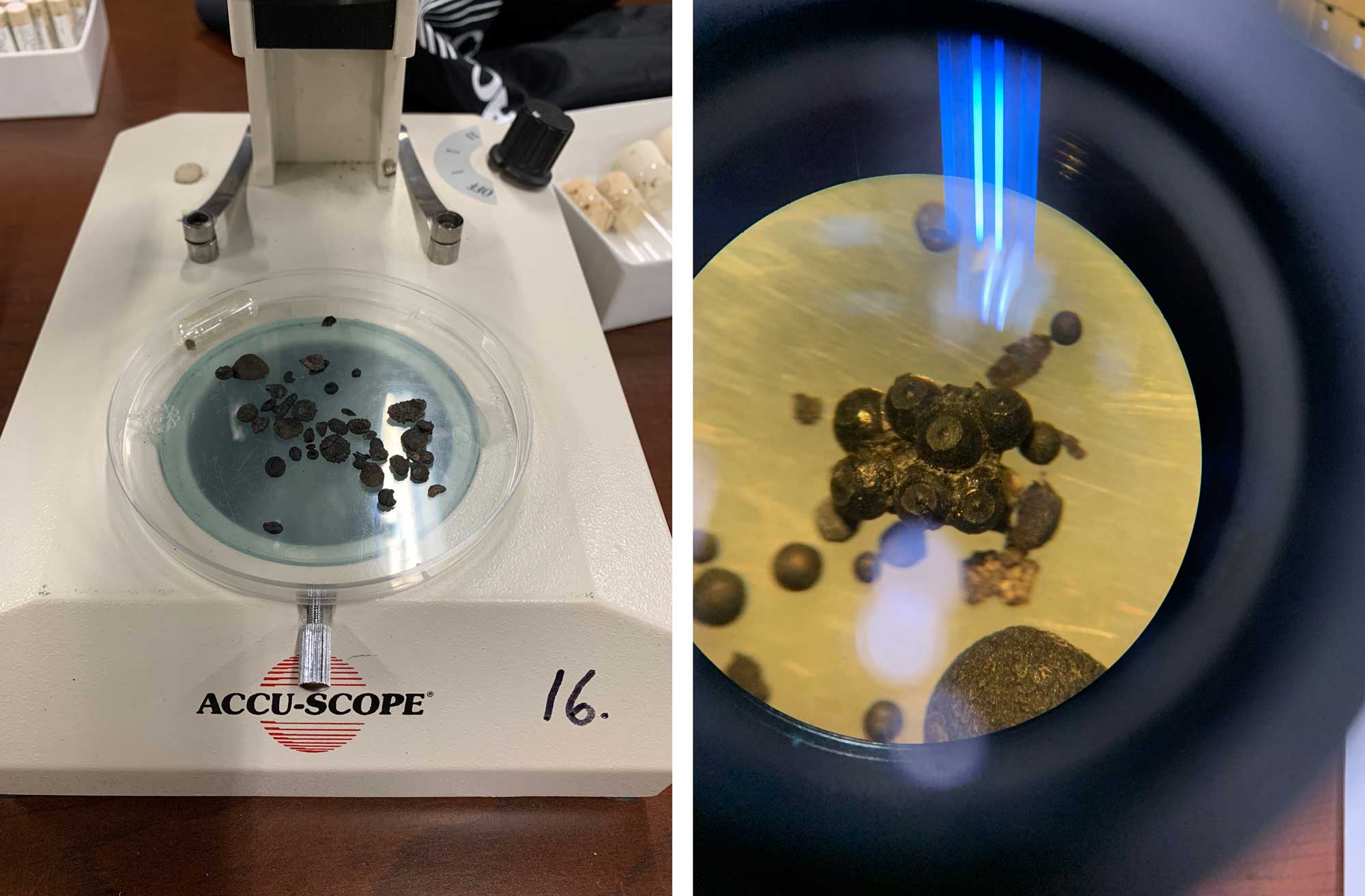

Gray Fossil Site is best known for its fossil vertebrates, but numerous plant fossils have also been found at the location. These plant fossils—which mostly consist of pollen, fruits, and seeds, but also include fragments of other plant parts—help paleontologists reconstruct the ancient environment at this locality. They also inform our understanding of the evolutionary histories of the plants themselves. A presentation about the plant fossil record of Gray Fossil Site by PRI's Dr. Elizabeth Hermsen is available to view here and is part of a series of "Paleo Talks" that covers all aspects of the biota of Gray Fossil Site.

Left: Fossil plant remains, including seeds and fruits, from Gray Fossil Site; many are small and require a microscope to study. Right: A fossil fungus viewed through a microscope eyepiece. Photographs by Elizabeth J. Hermsen.

Spotlight: Big Bone Lick State Park, Kentucky

Bones of Pleistocene mammals are widespread and locally abundant throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, western Virginia, West Virginia, and northern Alabama. They occur mainly in caves, sinkholes, and boggy deposits, and include mastodons, mammoths, giant sloths, and peccaries. Fossils of bats from the late Pleistocene (38,000 years ago) have been found in guano deposits in Mammoth Cave, Kentucky.

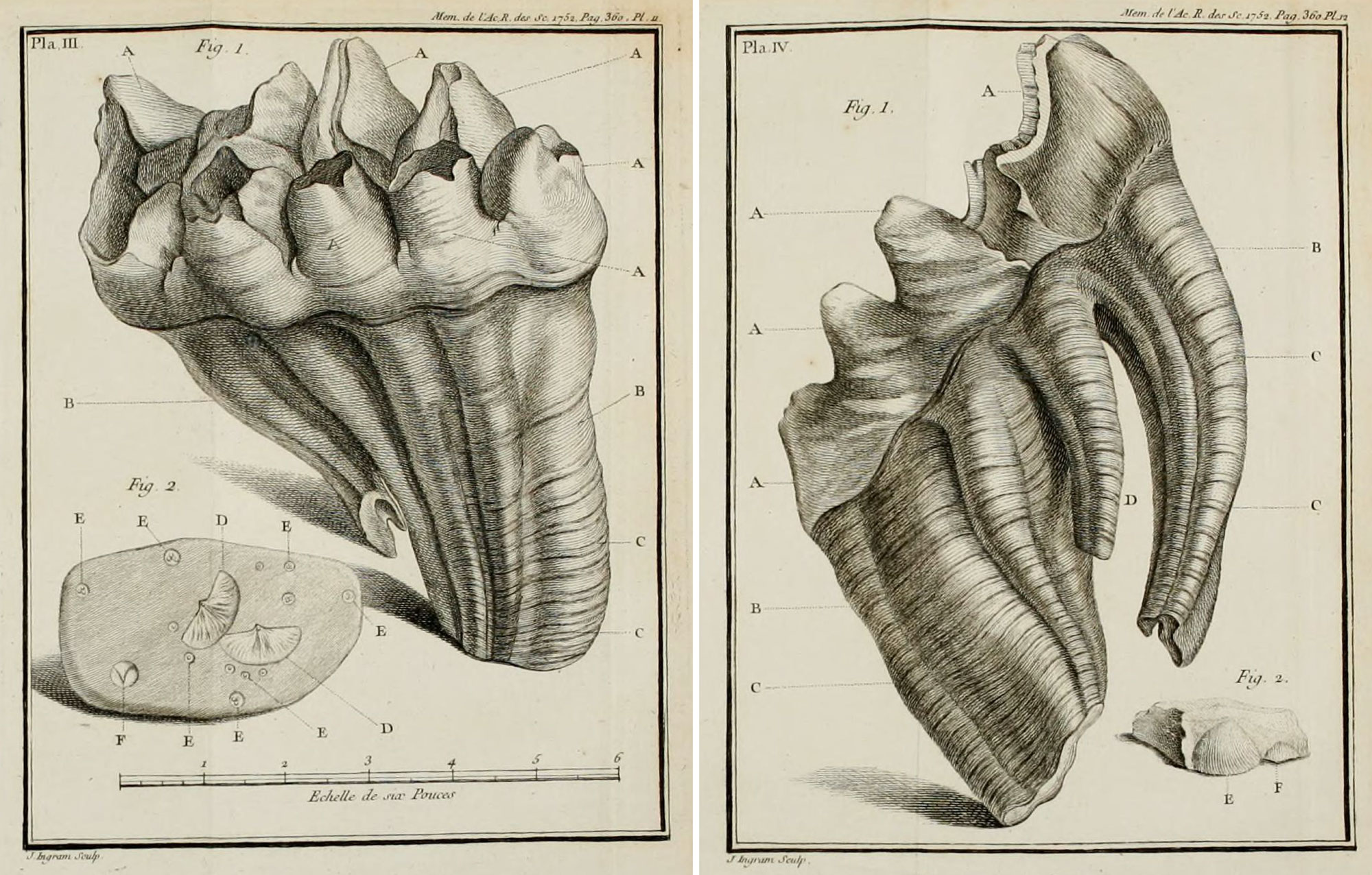

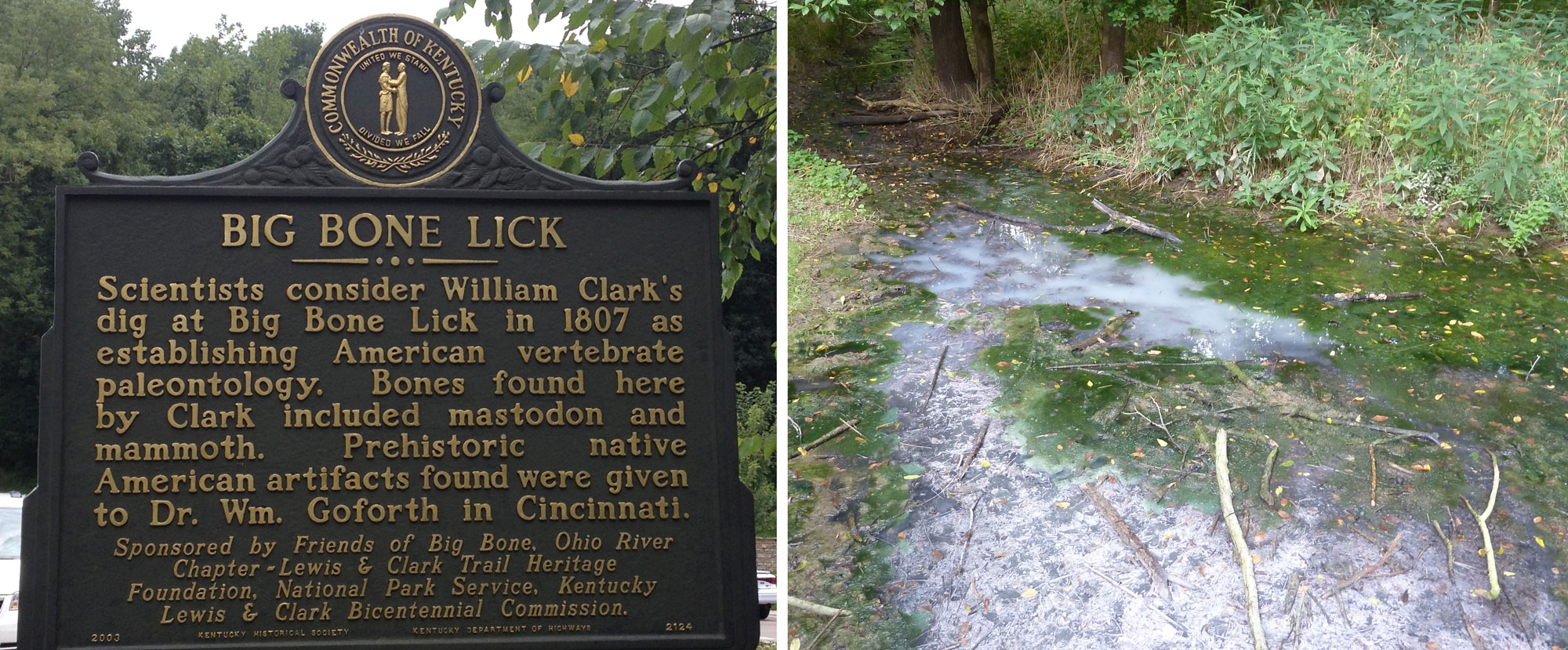

Perhaps the most famous Pleistocene mammal site in the region is Big Bone Lick, located less than 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) south of the Ohio River in Boone County, Kentucky. Big Bone Lick is sometimes called the "birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology." The first published illustration of a mastodon fossil (in 1756) was based on a tooth collected there in 1739, probably by Native American members of a French expedition. US President Thomas Jefferson acquired fossils from the site in 1808 that are now held at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, the Natural History Museum in Paris, and as part of Jefferson's personal collection at Monticello (an upper jaw bone from a mastodon remains on display at Monticello; see here).

Entryway sign at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky. Photograph by "albedo20" via flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license).

Illustrations of a mastodon tooth from Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, collected in 1739. These images were published in 1756. Drawings by J. Ingram, plates III and IV from Guettard (1756) Histoire de l'Académie royale des sciences, avec les mémoires de mathématique et de physique 1972: 182–220. (via Biodiversity Heritage Library, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported license, images cropped and resized).

Big Bone Lick gets its name from the large number of natural salt springs, or salt licks, in the area. During the late Pleistocene, these saline springs attracted numerous large mammals, many of which died and were buried there. The fauna includes an extinct horse (Equus complicatus), two giant ground sloths (Megalonyx jeffersonii and Paramylodon harlani), mammoths (Mammuthus sp.), mastodons (Mammut americanum), and caribou (Rangifer tarandus). Radiocarbon dating shows that the age of the bones at Big Bone Lick are between 11,000 and 12,300 years old.

Big Bone Lick, Kentucky. Left: Historical marker explaining why Big Bone Lick is the birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology. Right: Salt spring. Photographs by Jonathan R. Hendricks & Elizabeth J. Hermsen.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Atlas of Ordovician Life (by A. Stigall; covers southeastern Illinois, southwestern Ohio, and north-central Kentucky): https://www.ordovicianatlas.org/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Midwestern U.S.: Fossils of the Inland Basin (covers the Inland Basin in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio): https://earthathome.org/hoe/mw/fossils-ib/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland and Inland Basin (covers the Central Lowland and Inland Basin in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont): https://earthathome.org/hoe/ne/fossils-cl-ib/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/