Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Inland Basin region of the midwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; Paleozoic fossils; Ordovician fossils; Devonian fossils; Devonian marine invertebrate fossils; Devonian fossil sharks; Devonian placoderm fish; Carboniferous fossils; Carboniferous invertebrate fossils; Carboniferous fossil plants; Carboniferous vertebrate fossils; Pleistocene fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Fossils of the Midwestern US" by Alex F. Wall and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Midwestern U.S., edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 25, 2023.

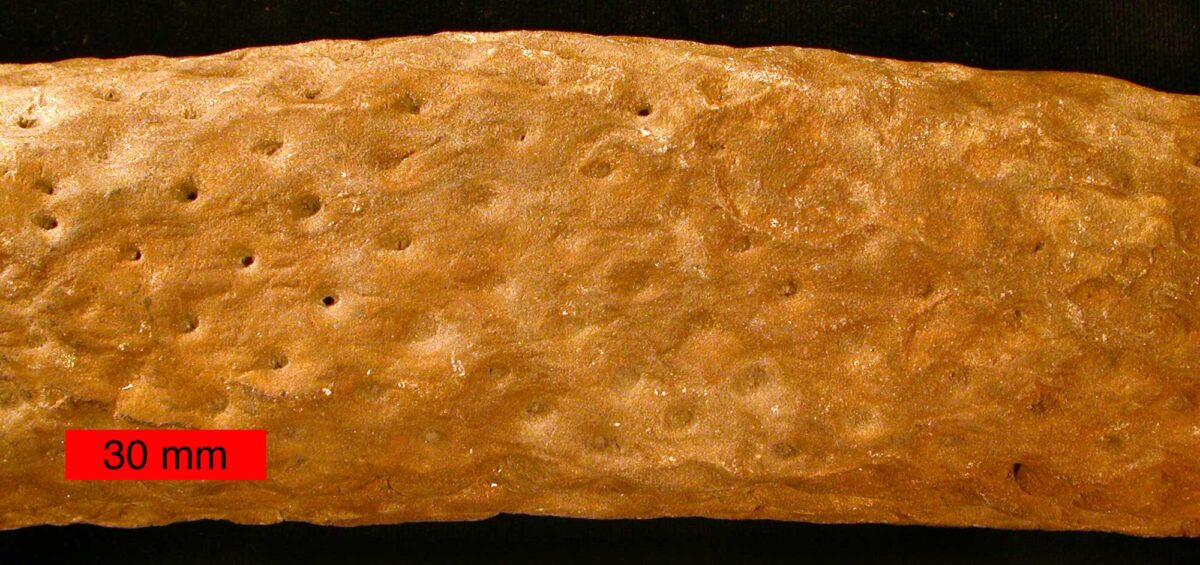

Image above: A rhizomorph (Stigmaria) from an ancient scale tree (Lepidodendrales, an extinct group of lycophytes), Carboniferous, northeastern Ohio. Rhizomorphs are root-like structures that anchored ancient lycophyte trees into the soil. The circular scars on the rhizomorph are sites where rootlets were once attached. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized).

Introduction

Much of the Inland Basin is located in the Northeastern United States, but the parts extending into the Midwest span nearly 100 million years of the Paleozoic Era. A band of rocks running from extreme northeastern to central southern Ohio are from the Devonian period, while most of the Inland Basin, including eastern Ohio, and the southern portions of Indiana and Illinois, is composed of younger Mississippian and Pennsylvanian rocks. The youngest bedrock of the region, from the Permian period, is located in the southeasternmost part of Ohio.

When the rocks of this region were formed, much of central North America was covered by a relatively shallow, tropical, inland sea. The late Devonian- and early Carboniferous-aged rocks of the Inland Basin contain the fossils of a diverse marine ecosystem. Younger Carboniferous rocks show the environment transitioning from the shallow sea to an environment of extensive deltas and swamps. These rocks contain the fossils of organisms from freshwater and forest ecosystems.

Paleozoic fossils

Ordovician fossils

Ordovician fossils are found in all seven Midwestern states, primarily in the Central Lowland region, but some Ordovician rocks outcrop in the Inland Basin as well. In the Ordovician, great reefs were formed by organisms like bryozoans, corals, algae, and sponges. These reefs played a major role in forming the ecosystems that were also home to straight-shelled cephalopods, trilobites, bivalves, gastropods, crinoids, graptolites, brachiopods, and fish.

A large trilobite (Isotelus maximus), Ordovician Waynesville Formation, Adams County, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license, image cropped, resized, rotated).

Devonian fossils

Devonian marine invertebrate fossils

During the Devonian period, what is now the Midwest was just south of the equator. Communities of corals, crinoids, bryozoans, brachiopods, and mollusks thrived in the warm sea that covered most of the Inland Basin. Numerous types of coral fossils and other invertebrates can be found in the region around Falls of the Ohio on the Indiana-Kentucky border.

Rugose coral (Cystiphylloides?), Devonian Jefferson Limestone, Clark County, Indiana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped, resized).

Tabulate coral (Favosites tuberosa), Devonian Jefferson Limestone, Clark County, Indiana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped, resized).

Brachiopods, Devonian Jefferson Limestone, Clark County, Indiana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped, resized).

Devonian fossil sharks

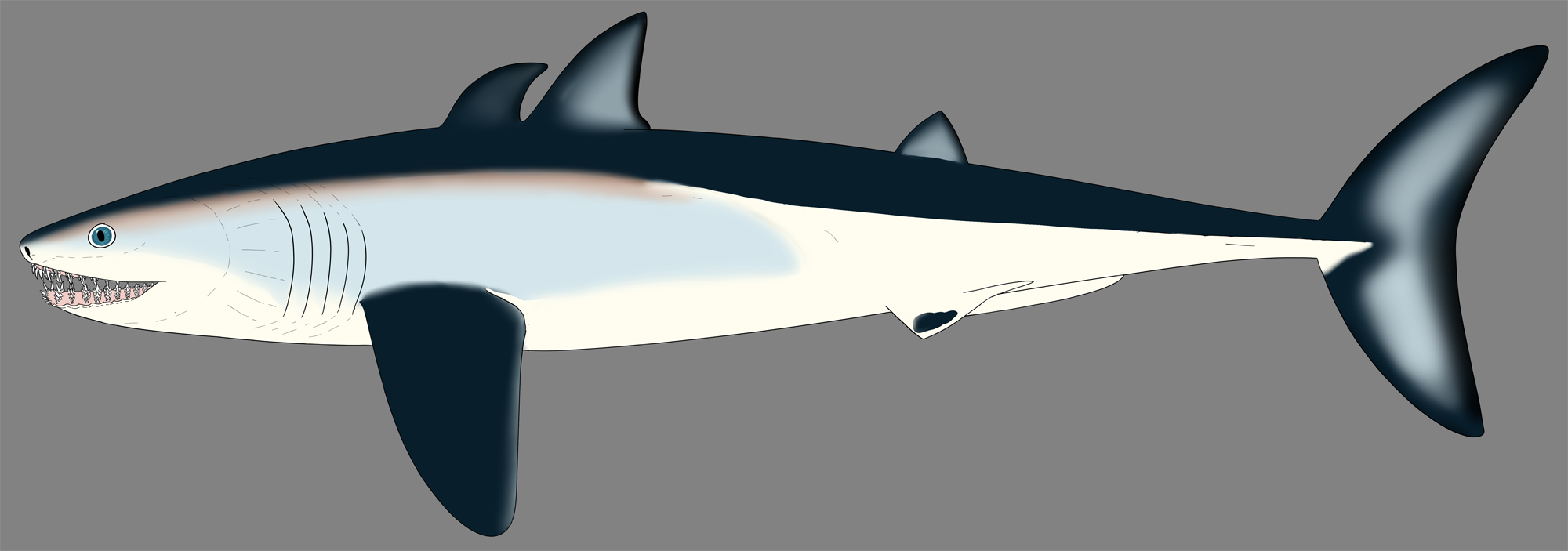

Sharks trace their lineage to the Ordovician, more than 420 million years ago, and they became increasingly diverse throughout the remainder of the Paleozoic Era. Ohio’s Cleveland Shale preserves specimens of the well-studied primitive shark Cladoselache. This shark was relatively common during the late Devonian and possessed an interesting blend of primitive and derived characteristics. Superficially, its body looked like that of a modern shark, but the 1.2-meter-long (4-foot-long) Cladoselache had a terminal mouth (rather than a mouth somewhat under the “nose” as in modern sharks), almost no scales, and no claspers (leaving scientists to wonder how they reproduced).

An ancient shark (Cladoselache fyleri) Devonian Ohio Shale, Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Reconstruction of the ancient Devonian shark Cladoselache fyleri. Reconstruction by EvolutionIncarnate (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Devonian placoderm fish

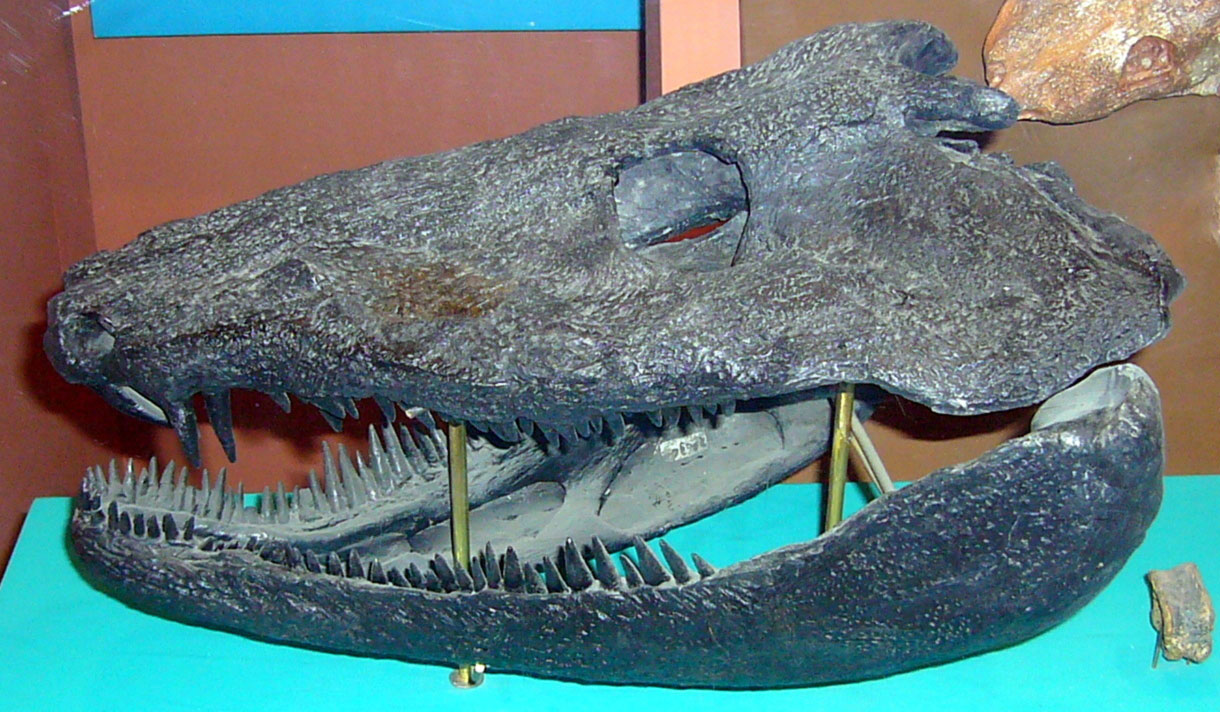

By the Devonian, fish had become increasingly prominent and diverse. The Devonian saw fishes explode in diversity, from tiny scavengers to huge hunters. The 9-meter-long (30-foot-long) Dunkleosteus did not have a bony internal skeleton, but its head was covered in bony armor. While remains of its soft parts, including its unarmored rear two-thirds, have yet to be discovered, the plates of numerous specimens have been found in the Cleveland Shale of Ohio, and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History houses the largest known specimens. The plates that formed the jaw functioned as huge blades, rubbing against each other to stay sharp as the fish chomped its prey: sharks, other fish, and large invertebrates. Dunkleosteus is thought to have had one of the most powerful bites in the history of life, and it was the apex predator of the late Devonian seas. Despite its apparent advantages, it and all of its its placoderm kin became extinct at the end of the Devonian.

Cast of a Dunkleosteus skull on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York.

Carboniferous fossils

Carboniferous invertebrate fossils

During the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian, the expansion and contraction of glaciers far to the south caused sea levels to fluctuate. In the ocean, brachiopods, trilobites, and reef builders were decimated by the mass extinction at the end of the Devonian. The Mississippian is sometimes known as the “Age of Crinoids” because of the increase in the abundance and diversity of crinoids, as well as starfish, edrioasteroids, urchins, and other echinoderms during this time.

Original description: "Bivalves (Aviculopecten) and brachiopods (Syringothyris) in the Logan Formation (Lower Carboniferous) of Wooster, Ohio." Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized).

A blastoid (Pentremites godonii), Mississippian Indian Springs Formation, southern Indiana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped, resized).

Carboniferous fossil plants

The oldest known fossils of land plants are isolated spores dating to the Ordovician Period. By the late Silurian, fossils of simple, leafless stems just a few centimeters tall are found in sediments that accumulated in low, wet, coastal environments. The first trees and the first seeds date to the Devonian period. By the end of the Devonian, extensive forests containing many different kinds of trees and other plants had developed.

During the Carboniferous (and especially the Pennsylvanian), what is now the Interior Basin region of the Midwest was a broad, low coastal plain near the Equator. It was home to extensive swamp forests. These ancient ecosystems are sometimes called “coal swamps” because the stagnant, wet environments in which they thrived prevented large volumes of vegetation from decomposing. As the plant matter accumulated for tens of millions of years, it formed thick, extensive deposits of coal underlying much of the Central Lowland as well as the parts of the Inland Basin.

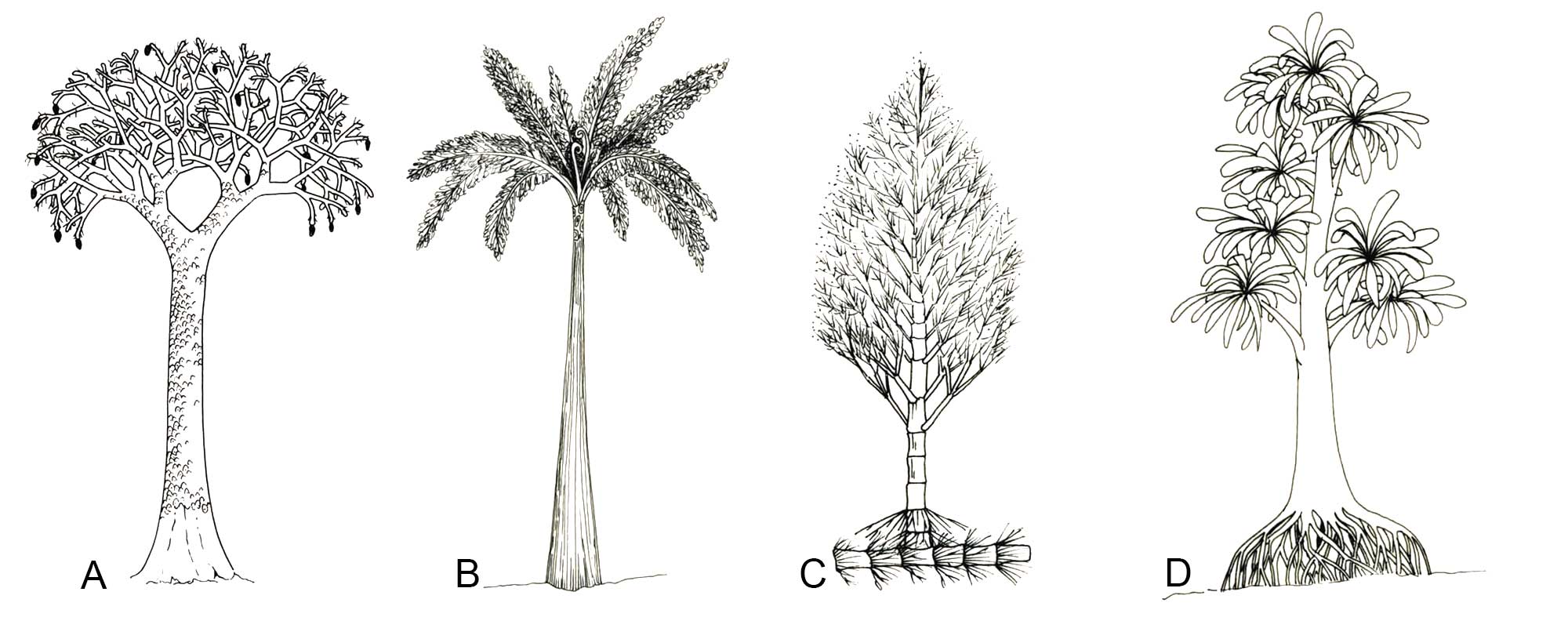

The trees found in these forests did not belong to the familiar groups that dominate modern forests, such as conifers and flowering broadleaf plants. Instead, these early forests were made up of groups of plants that are either extinct or much less conspicuous today. These groups were the lycophytes (club mosses and relatives), the sphenophytes (horsetails and relatives), the marattioid ferns, seed ferns (seed-producing plants with fern-like leaves), and the cordaites (a group related to conifers). Lycophytes and horsetails survive today, but often small, non-woody plants. Marattioid ferns are restricted to the tropics. Cordaites and seed ferns are extinct.

In some areas of the Inland Basin, such as in the Steubenville, Ohio, anatomically preserved Carboniferous plants can be found in coal balls. Coal balls are nodules of peat (accumulated plant matter) preserved in calcium carbonate. The plant remains inside a coal ball are often exquisitely preserved, showing cells, tissues, and other microscopic structures.

Restorations of Pennsylvanian coal swamp trees. A. Scale tree (Lepidodendron), a lycophyte that reached 30 m (100 ft) tall. B. Psaronius, a marattioid tree fern, reached 3 m (10 ft) tall. C. Calamites, a sphenophyte (horsetail), reached 20 m (65 ft) tall. D. Cordaites, a conifer-like seed plant; reached 10 m (35 ft) tall. Illustration by Christi Sobel.

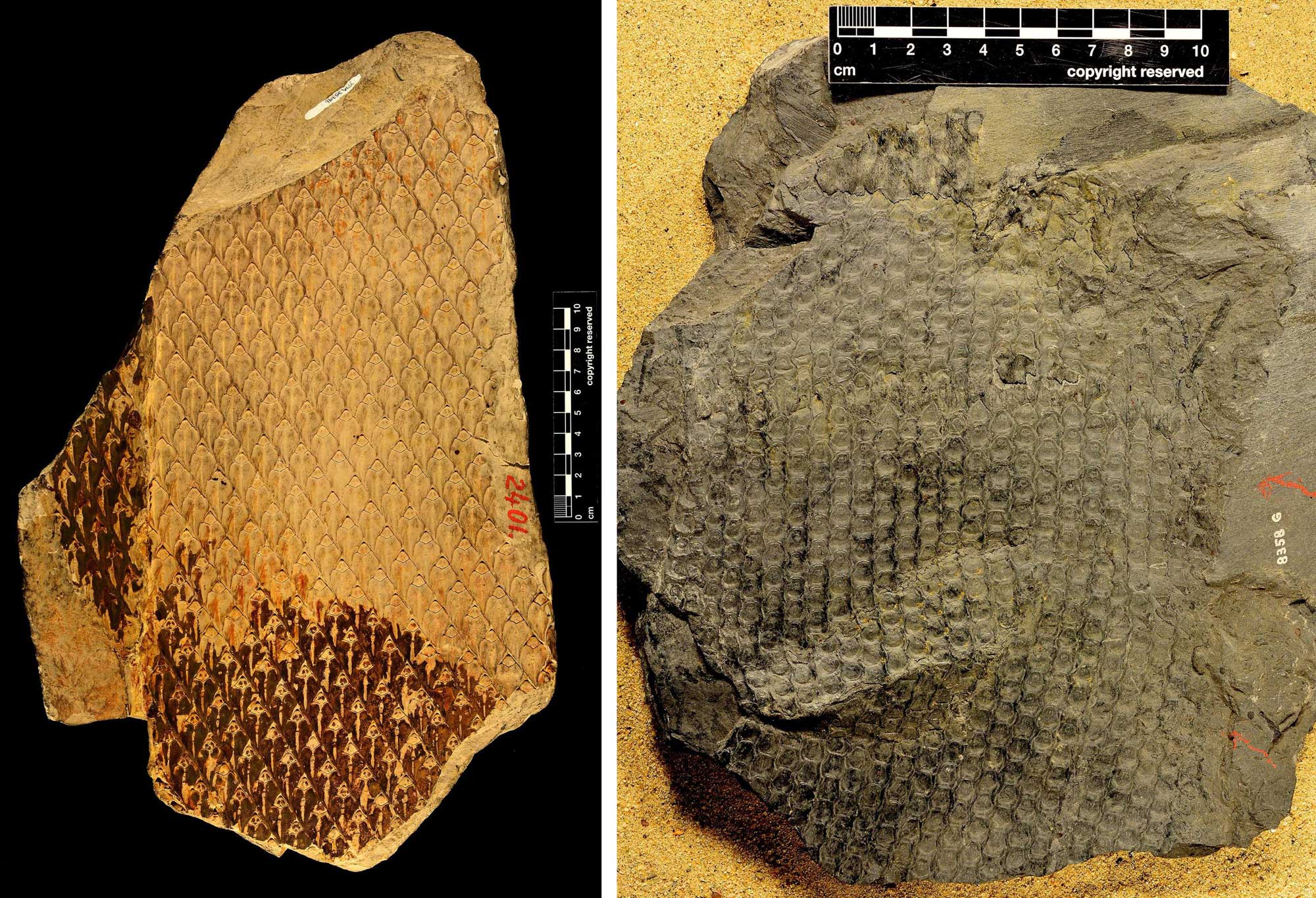

Scale trees (Lepidodendrales), an extinct group of lycophytes, Carboniferous. The "scales" forming the patterns on the trunks and branches of these trees are actually leaf cushions, scars left behind after leaves were shed. The shapes of the leaf cushions are important in identification. Left: Lepidodendron (YPM PB 035396), Orange County, Indiana. Right: Sigillaria elegans (YPM PB 035538), Summit County, Ohio. Photos by Robert Swerling (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Foliage of ancient sphenophyte trees (Annularia and Asterophyllites), Pennsylvanian Allegheny Formation, Muskingum County, Ohio. Photo of YPM PB 172840 by Fiona O'Brien (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Part of a stem or rhizome (underground stem) of an ancient sphenophyte tree (Calamites approximatus), Summit County, Ohio. Specimens with this type of preservation are often interpreted as pith casts (casts of the center of the stem). The ribbed and jointed stem is characteristic of horsetails. Photo of YPM PB 035609 by Robert Swerling (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Remains of marattioid ferns, Ohio. Left: Cross section of a permineralized root mantle (Psaronius), Meigs County (age not specified, probably Carboniferous). Right: Base of a frond (Pecopteris arborescens), Carboniferous, Jefferson County. Left photo of YPM PB 063539 by Robert Swerling, 2020 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication). Right photo of YPM PB 055061 by Fiona O'Brien, 2020 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Remains of seed ferns in the order Medullosales, Carboniferous, Ohio. Left: Foliage (Neuropteris lancifera), Summit County. Right: A seed (Trigonocarpus trilocularis), Massillon Sandstone. Left photo of YPM PB 027415 by Linda S. Klise (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication). Right photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

"Coal Ball Fossils." This video discusses coal ball fossils and shows how they are processed for study. Note: This is an old video and the picture quality is poor. Source: Richard Crang (via YouTube).

Carboniferous vertebrate fossils

At the end of the Devonian, fluctuations in sea level caused the water to retreat from portions of the Inland Basin. By the beginning of the Carboniferous, the landscape was dominated by deltas and swampy forests, similar to what occurred in the Central Lowland region at this time. In addition to plants, the fossils of freshwater fish, sharks, early amphibians, and arthropods can be found in coal beds from the late Carboniferous. At the beginning of the Permian, Ohio was a terrestrial environment where lake and river deposits preserved horsetail and fern fossils. These are the youngest fossils found in the Inland Basin’s bedrock.

Shark teeth (Petalodus ohioensis), Pennsylvanian, Guernsey and Noble counties, Ohio. Left photo of USNM PAL 244454 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain). Right photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

An embolomere (Neopteroplax conemaughensis), Pennsylvanian Casselman Formation, Jefferson County, Ohio. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

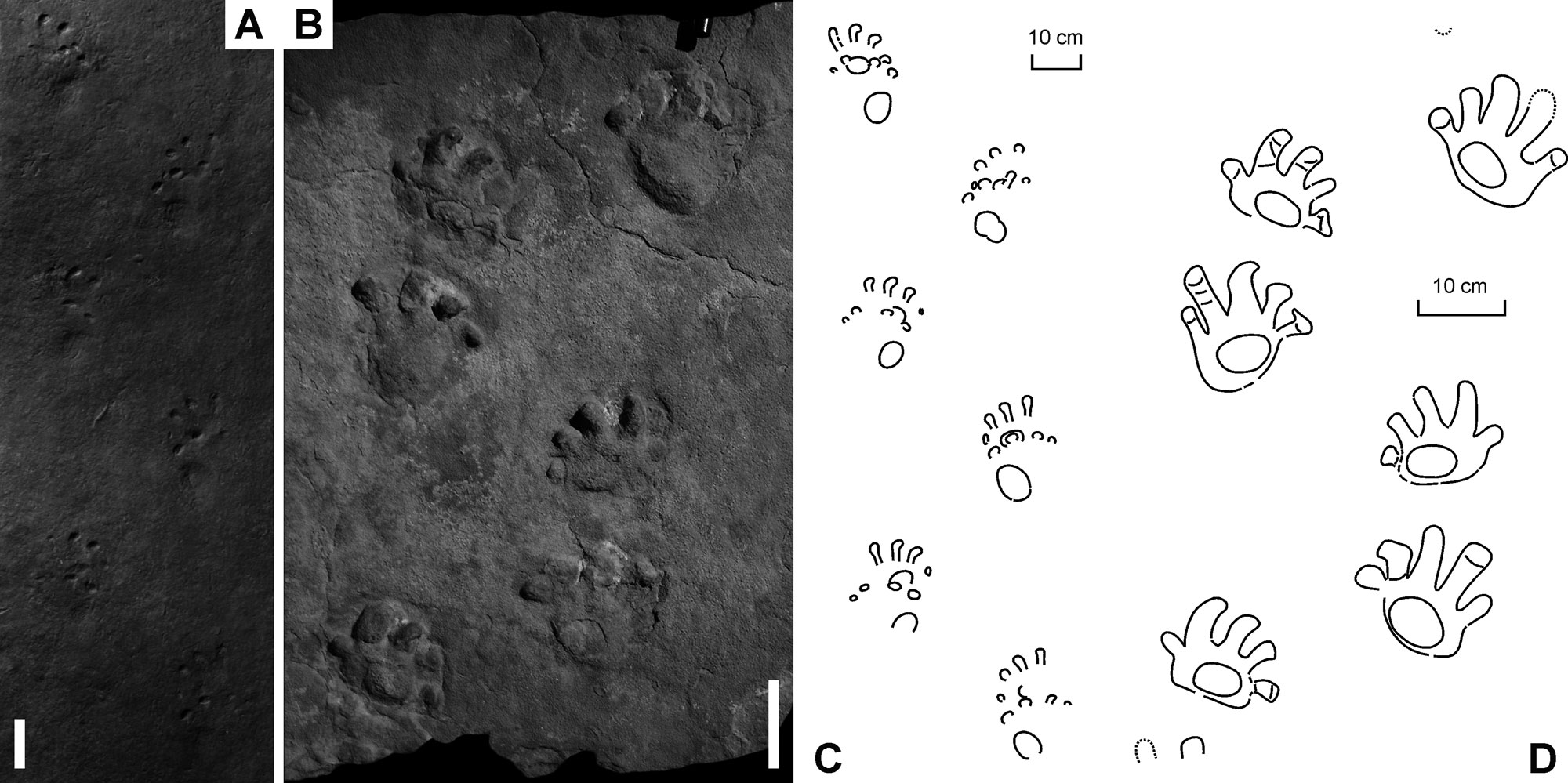

Vertebrate trackways (Ichniotherium) from the Carboniferous Monongahela Group, Ohio. A, C: Photo and drawing of trackway previously called "Baropus hainesi". B, D: Photo and drawing of trackway previously called "Megabaropus hainesi." Scale bars = 10 centimeters (3.9 inches). Source: Figure 6 from Buchwitz and Voigt (2018) PeerJ 6:e4346 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Ichniotherium footprint from the Pennsylvanian Monongahela Group, Morgan County, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Pleistocene fossils

About 2.6 million years ago, permanent ice sheets formed in the Northern hemisphere, marking the beginning of the Quaternary period (which extends to the present). During this time, glaciers repeatedly scraped their way southward across the Midwest and melted back northward. Much of the Inland Basin region in the Midwest was never glaciated, although glaciers reached northeastern Ohio. The glaciers began to retreat from the Midwest about 15,000 years ago, leaving behind the landscape we see today.

Large vertebrates lived in the Inland Basin region during the Pleistocene, and their remains are discovered from time to time. These include extinct relatives of elephants, the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primogenius) and the American mastodon (Mammut americanum). One of the most notable mastodons from the Inland Basin is the Burning Tree Mastodon. This mastodon, which is over 11,000 years old, was found on the Burning Tree Golf Club (now the Mastodon Golf Club) in Licking County, Ohio, in 1989. It is one of the most complete mastodons ever discovered and is especially notable for its remarkable preservation. Scientists think that marks on its ribs were made by humans who butchered the animal for its meat. The Burning Tree Mastodon was sold to Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Natural History in Japan in the early 1990s; a replica of the skeleton is on display at Hanover College in Hanover, Indiana.

Mammoth (Mammuthus) tooth, Pleistocene, Holmes County, Ohio. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Mastodon (Mammut) tooth, Pleistocene, Holmes County, Ohio. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Excavation of the Burning Tree mastodon in 1989. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland and Inland Basin (covers the Central Lowland and Inland Basin in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont): https://earthathome.org/hoe/ne/fossils-cl-ib/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Inland Basin (covers the Inland Basin in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia): https://earthathome.org/hoe/se/fossils-ib

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/