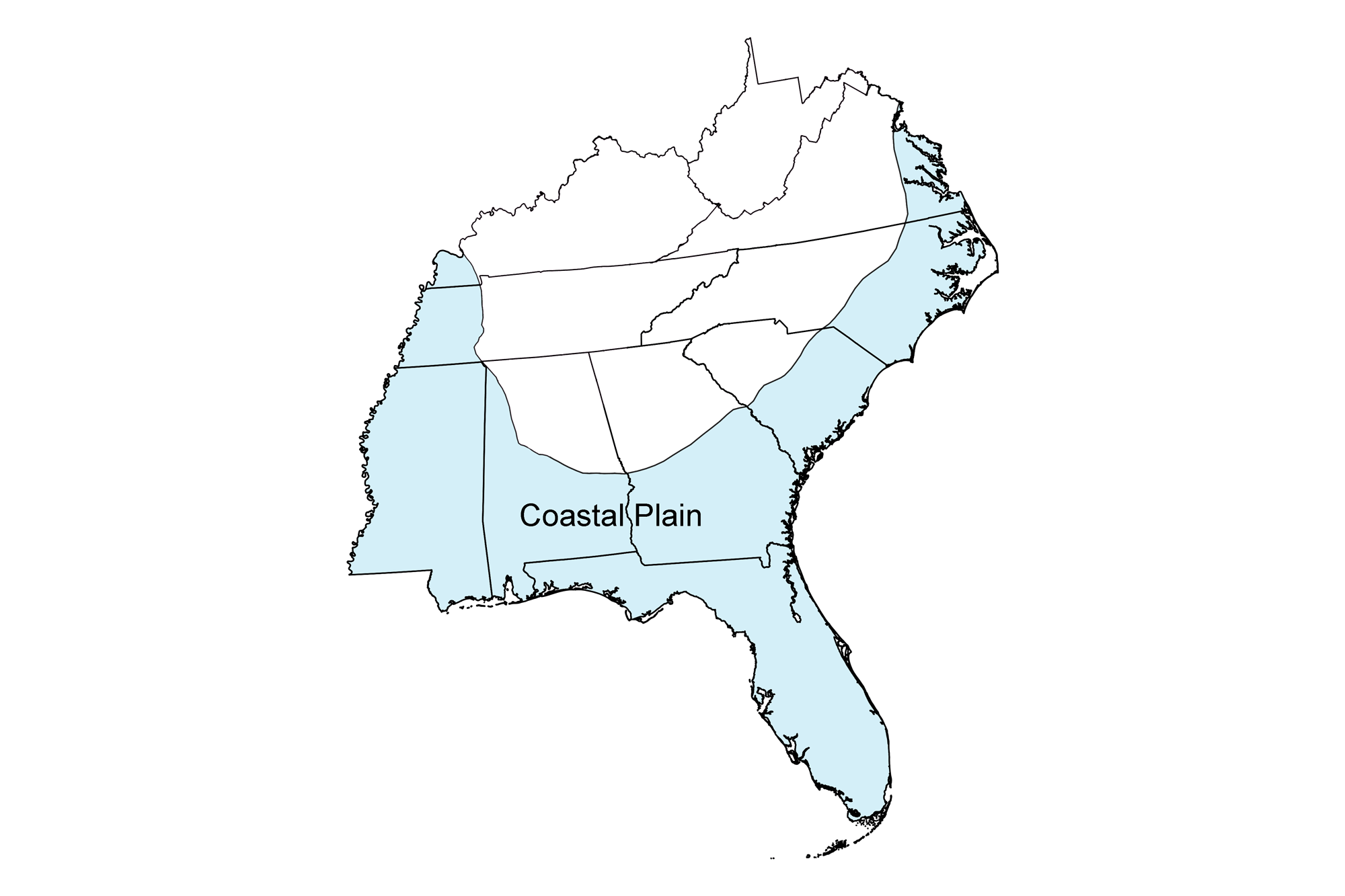

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Coastal Plain region of the southeastern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils, Mesozoic fossils, Mesozoic marine fossils, Mesozoic terrestrial fossils, Cenozoic fossils, Cenozoic marine fossils, Cenozoic marine invertebrates, Cenozoic sharks and rays, Cenozoic marine mammals, Cenozoic terrestrial fossils, Cenozoic birds, Cenozoic mammals, Cenozoic plants; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Fossils of the Southeastern US" by Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S., 2nd ed., edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated February 25, 2022.

Image above: A deposit of fossil shells and corals from the Pliocene to Pleistocene of Florida. Photo by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Paleozoic fossils

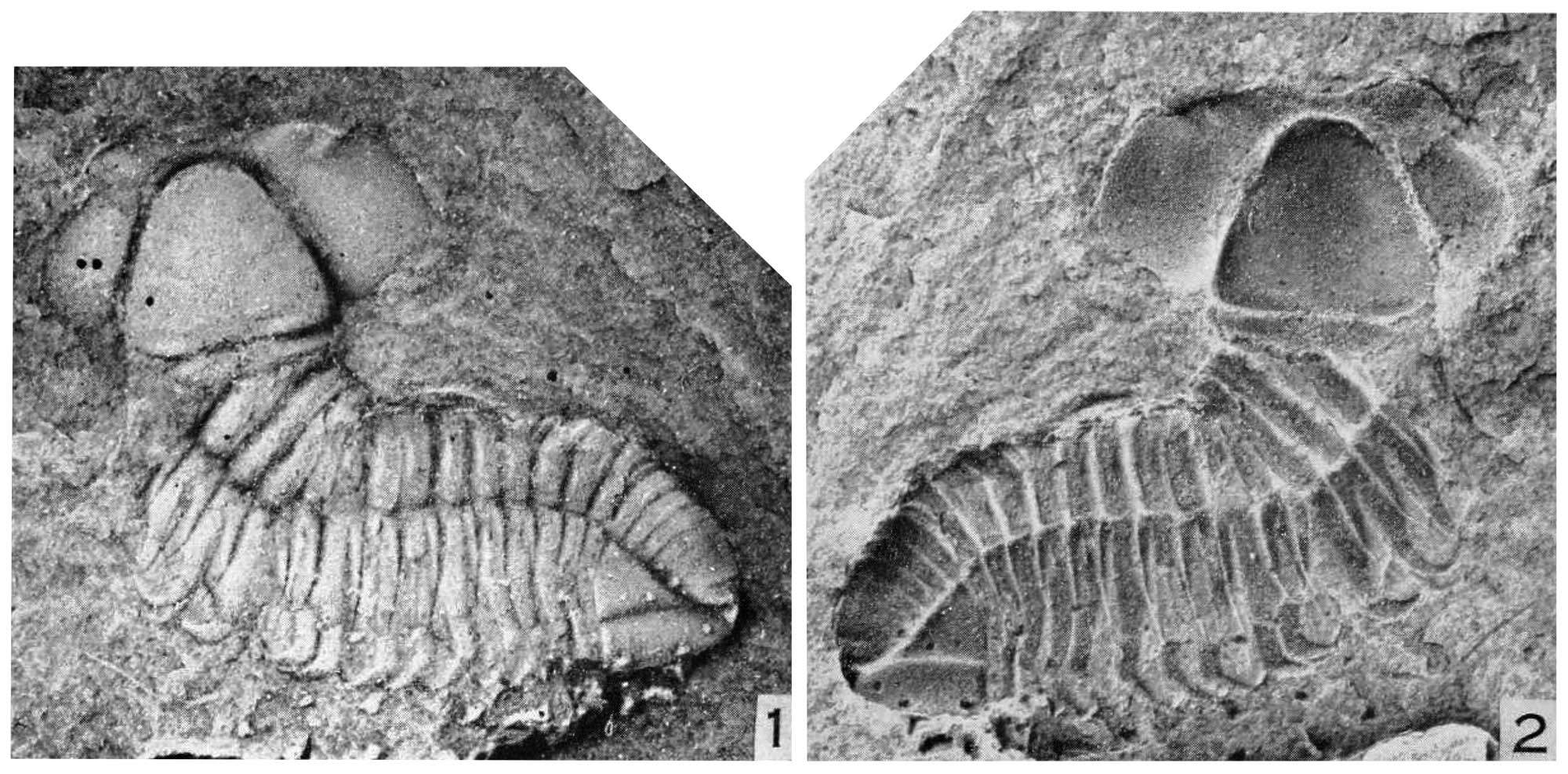

There are no rocks at the surface in Florida older than Eocene in age (approximately 55 million years old), but older rocks and fossils have been found in cores drilled deep below the surface. The oldest of these rocks dates to the early Ordovician period, about 480 million years ago, as determined by index fossils such as graptolites and brachiopods. The only trilobite ever found in Florida is a single specimen from one such core, drilled in Madison County, at a depth of around 1570 meters (4630 feet). It was described by Harry Whittington in 1953 and is known today as Plaesiacomia exsul.

The trilobite Plaesiacomia exsul (Whittington, 1953), recovered from middle Ordovician rocks in a deep core from northern Florida. Field of view approximately 1.4 centimeters (0.7 inches) wide. Original caption: "Fig. 1. Rubber mould of holotype. The black spots on the left side of the cephalon [head] are caused by minute holes in the mould. Fig. 2. Holotype, external mould." Specimen is in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Image from Whittington (1953) in Brevoria (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license; image modified from original.).

Mesozoic fossils

Mesozoic marine fossils

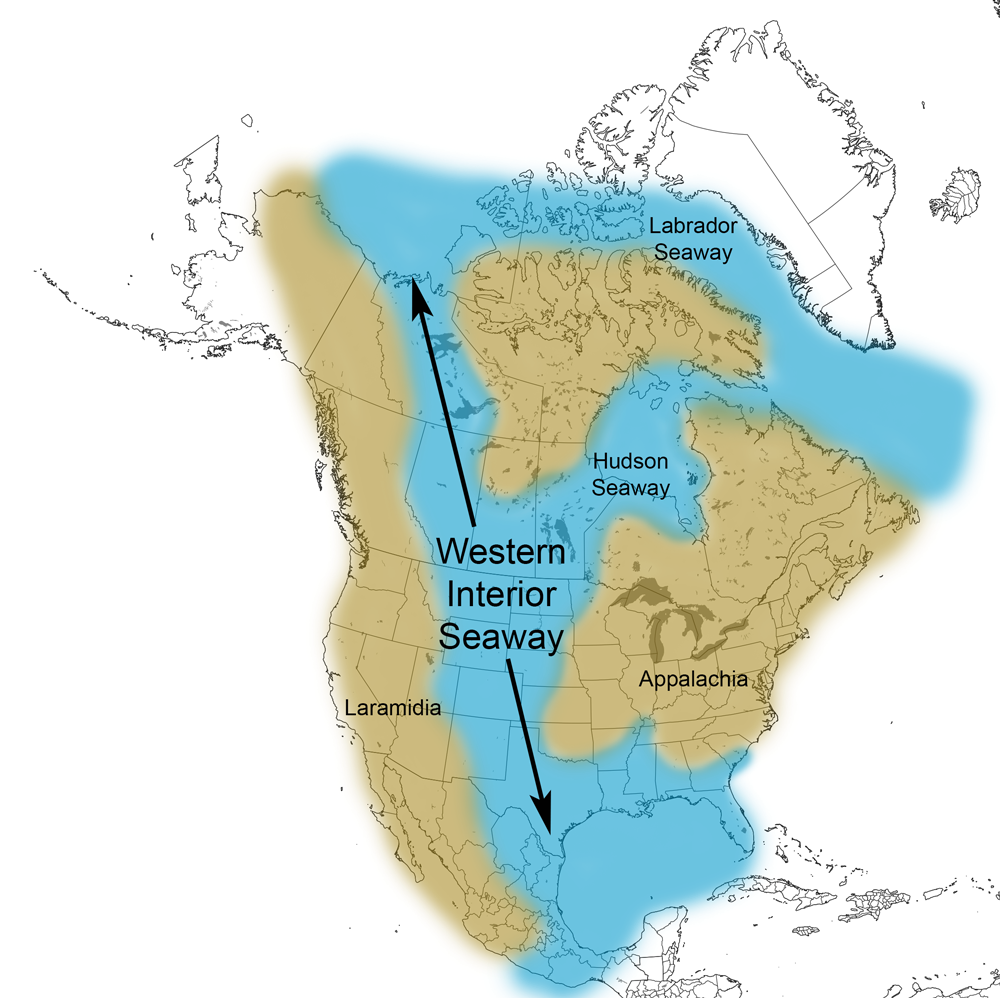

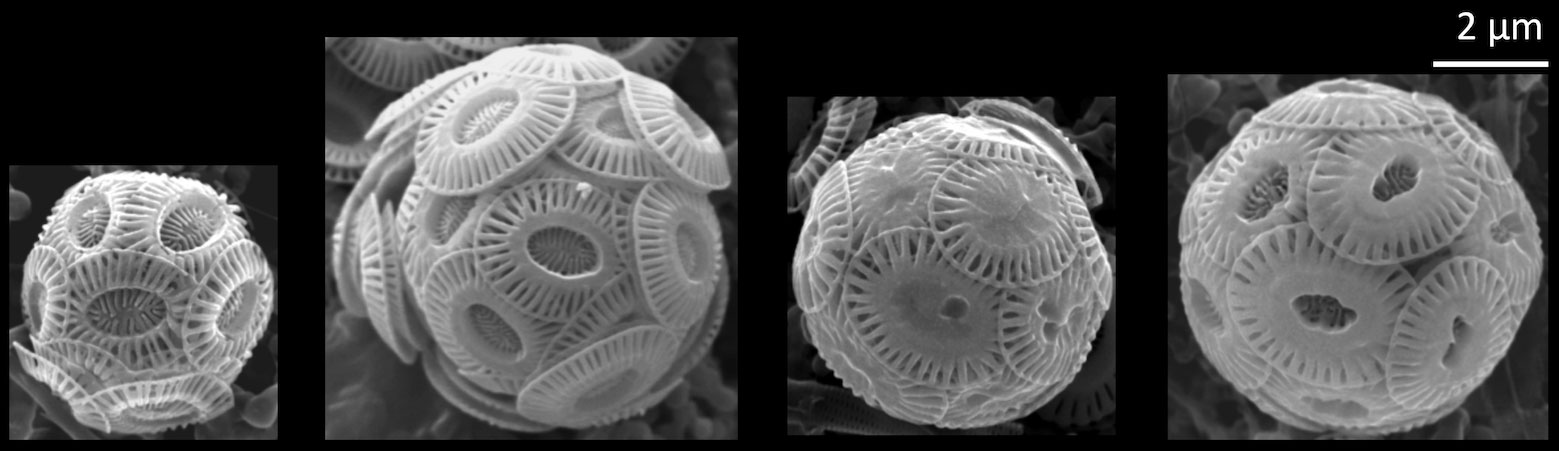

During the Cretaceous, the Western Interior Seaway stretched across the center of North America from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to the Arctic Ocean in the north, and from the Rocky Mountain states in the west to Iowa in the east. Chalk was deposited in some areas of this seaway. Chalk is mostly made up of the calcium carbonate plates (coccoliths) formed by microscopic marine algae called coccolithophores.

Extent of the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous Period. Image from Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Modern coccolithophores (Emiliana huxleyi) from the Mediterraenan Sea. The oval-shaped plates making up each sphere are coccoliths. Image modified from fig. 2 in D'Amario et al. (2018) PLoS ONE 13(7): e0201161 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Today, chalky sediments accumulate mainly in the deep sea. During the Cretaceous, when sea levels were much higher than they are today, thick chalk deposits accumulated in the shallow continental seas. The Cretaceous Period, in fact, is named for the abundance of chalk that was deposited during this time. (The Latin word for chalk is creta.) Cretaceous chalk is common across much of central Alabama. Chalk deposits also occur in northeastern Mississippi.

Cretaceous chalk deposits of the Coastal Plain. Left: Jones Bluff on the Tombigbee River, Alabama, where bluffs formed by Selma Group Chalk are exposed. Image from plate V in Stephenson (1914) USGS Professional Paper 81. Right: Prairie Bluff Chalk, Starkville, Mississippi, in 2010. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wilson44691, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal license/Public Domain Dedication).

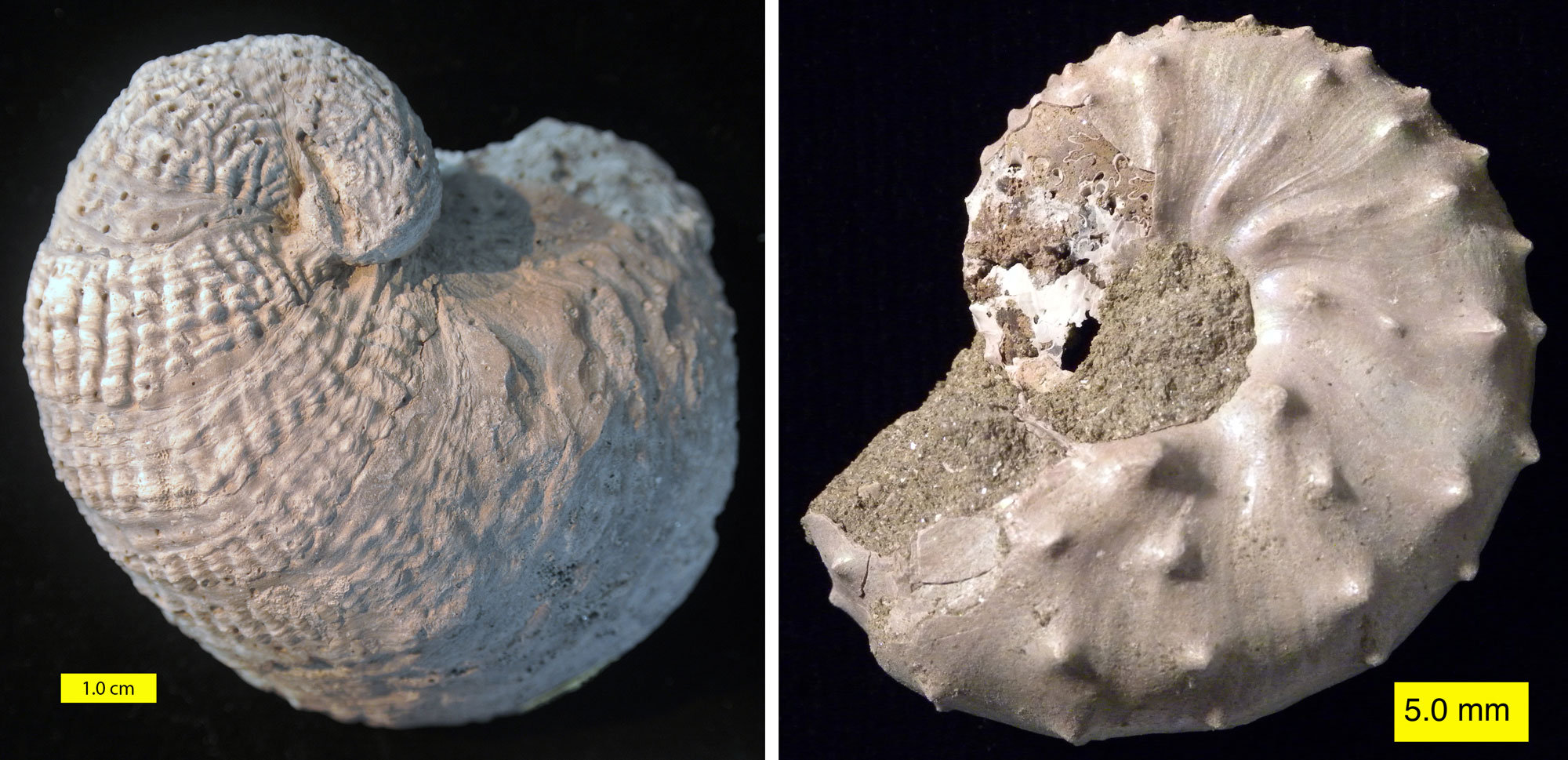

Cretaceous marine sediments of the Coastal Plain are often rich in both invertebrate and vertebrate fossils. Mollusks are especially common, including gastropods (snails), bivalves (clams and relatives), and cephalopods (the group including octopuses and squid), such as ammonites and belemnites. Crabs are also sometimes locally abundant. Vertebrates include sharks and marine reptiles, such as mosasaurs and, more rarely, plesiosaurs.

Marine invertebrate fossils from the Cretaceous of Mississippi. Left: A fossil oyster (Exogyra costata) from the Prairie Bluff Formation, Starkville, Mississippi. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wilson44691, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal license/Public Domain Dedication). Right: An ammonite (Discoscaphites iris) from the Owl Creek Formation, Ripley, Mississippi. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wilson44691, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain).

Shark teeth (Cretalamna bryanti) from the Cretaceous Mooreville Chalk of Alabama. Scale bars are 1 cm (about 0.4 in). Figure 7 from Ebersole and Ehret (2018) PeerJ 6:e4229 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

The mosasaur Globidens alabamensis from the Cretaceous Mooreville Chalk of Alabama. Left: Portion of a lower jaw. Image from the Smithsonian Learning Lab (CC0/Public Domain). Right: Reconstruction of the G. alabamensis by Dmitry Bagdanov (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image modified from original). Globidens alabamensis was about 6 m (20 ft) long and ate mollusks.

Mesozoic terrestrial fossils

Dinosaur fossils are not common in Coastal Plain sediments, thanks to the absence of Cretaceous-aged terrestrial deposits. Nevertheless, dinosaurs have been found in almost every state in the region. They include both herbivores (mostly hadrosaurs or "duckbills") and carnivores (theropods). Coastal Plain dinosaur fossils come from marine sediments and were preserved when dinosaur carcasses floated out to sea. Most of these fossils are isolated bones or partial skeletons, making them difficult to identify. Perhaps one of the most interesting dinosaur finds is an Ornithomimus egg from Harrell Station fossil site in Alabama.

Reconstruction of the full skeleton of Appalachiosaurus montgomeriensis, a theropod dinosaur from the Cretaceous (about 77 million years ago), Demopolis Formation, Alabama. Photo by Jonathan Chen (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Images of a ceratopsid tooth from the Cretaceous Owl Creek Formation of Mississippi. Ceratopsids, or horned dinosaurs, are the group that includes dinosaurs like Triceratops. Scale bar = 1 cm (0.4 in). Images from figure 5 of Farke and Phillips (2018) PeerJ 5: e3342 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

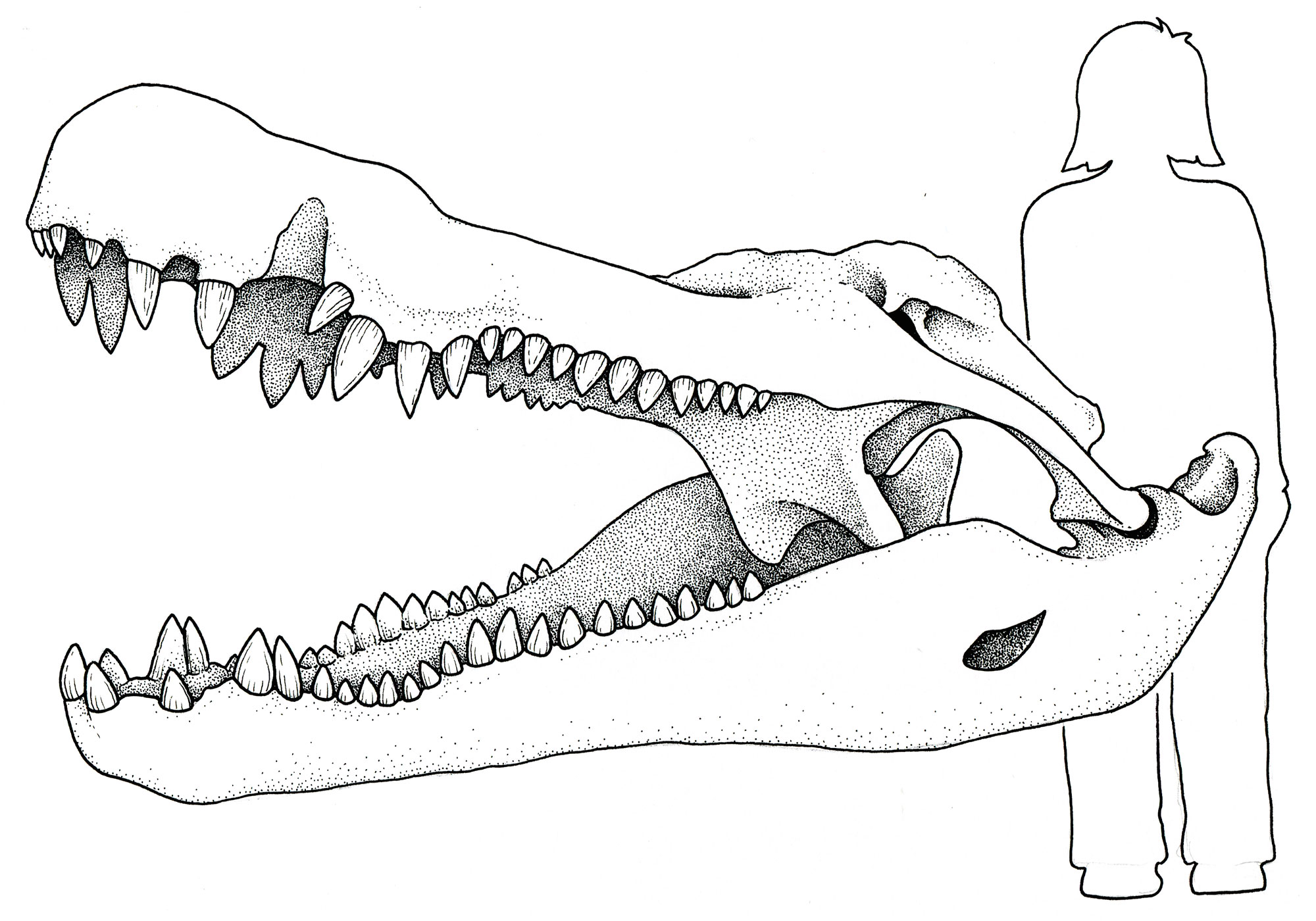

Other reptile groups are also known from Cretaceous sediments of the Coastal Plain. Pterosaurs (flying reptiles) have been found in North Carolina and Georgia. The giant crocodilian Deinosuchus, which reached lengths of up to 12 meters (39 feet), lived on both eastern and western sides of the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous Period. In the eastern United States, it is found from New Jersey to Alabama.

Skull of Deinosuchus next to an adult human. Drawing by Christi Sobel (copyright Christi Sobel).

Despite the lack of terrestrial sediments in the Coastal Plain, fossils of Cretaceous land plants are known from a number of localities. These deposits formed in nearshore environments where land plants washed into coastal marshes. They include fossil leaves, fruits, and flowers. Some plant fossils, like those from the Ingersoll Shale of eastern Alabama, are extremely well preserved. Tiny fossils of flowers and fruits have also been found in Cretaceous sediments in Virginia and Georgia. Late Cretaceous amber (fossil tree resin) is known from several places, including Russell County, Alabama, and Tishomingo County, Mississippi.

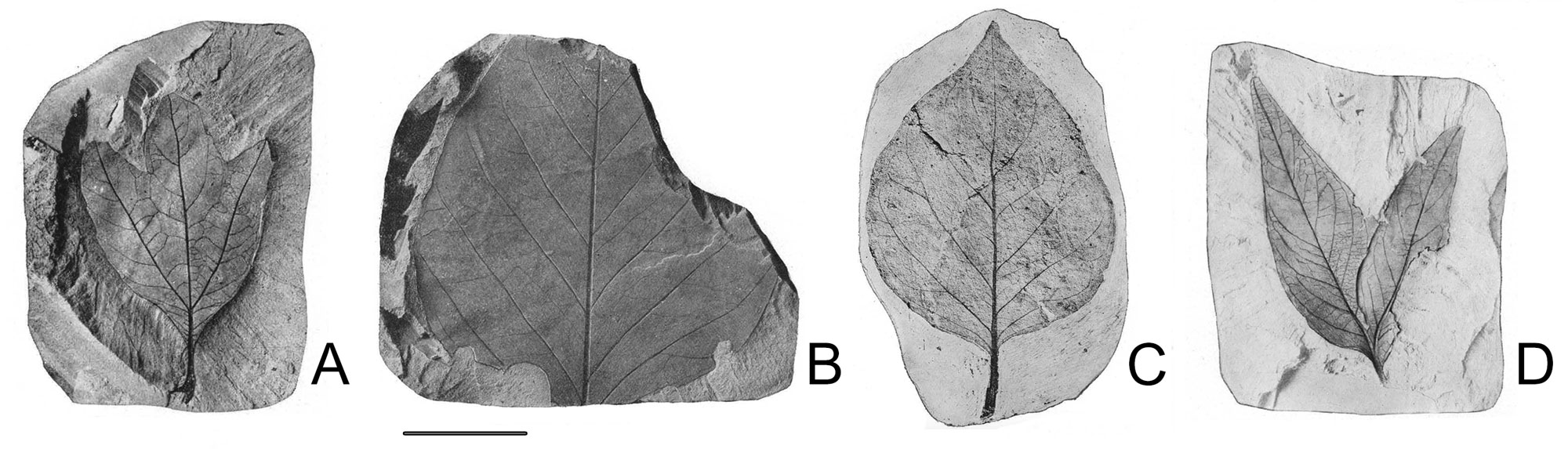

Leaf fossils from the Cretaceous Tuscaloosa Formation, Alabama. A. Sycamore (Platanus shirleyensis). B. Magnolia (Magnolia lacoeana). C. Cordia apiculata. D. Hymenaea fayetensis. Scale bar = 1 cm (0.4 in). Images from Berry (1919) USGS Professional Paper 112.

Cenozoic fossils

Cenozoic marine Fossils

Marine invertebrates

Paleogene sediments of the Coastal Plain have been studied since the early 1800s, longer than almost any other fossil-bearing sediments in the Americas. Coastal Plain deposits are often very fossiliferous and some are among the most famous Paleogene fossil beds in the world.

Fossil mollusks—mainly clams and snails—of Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene age occur across the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal Plains, from Texas to Maryland. They are frequently found in beautifully preserved shell beds that may contain hundreds of different species. For example, the Middle Eocene Gosport Sand in southwestern Alabama contains more than 500 species of fossil mollusks. In total, more than 3000 species of mollusks have been described from the Paleogene of the Coastal Plain.

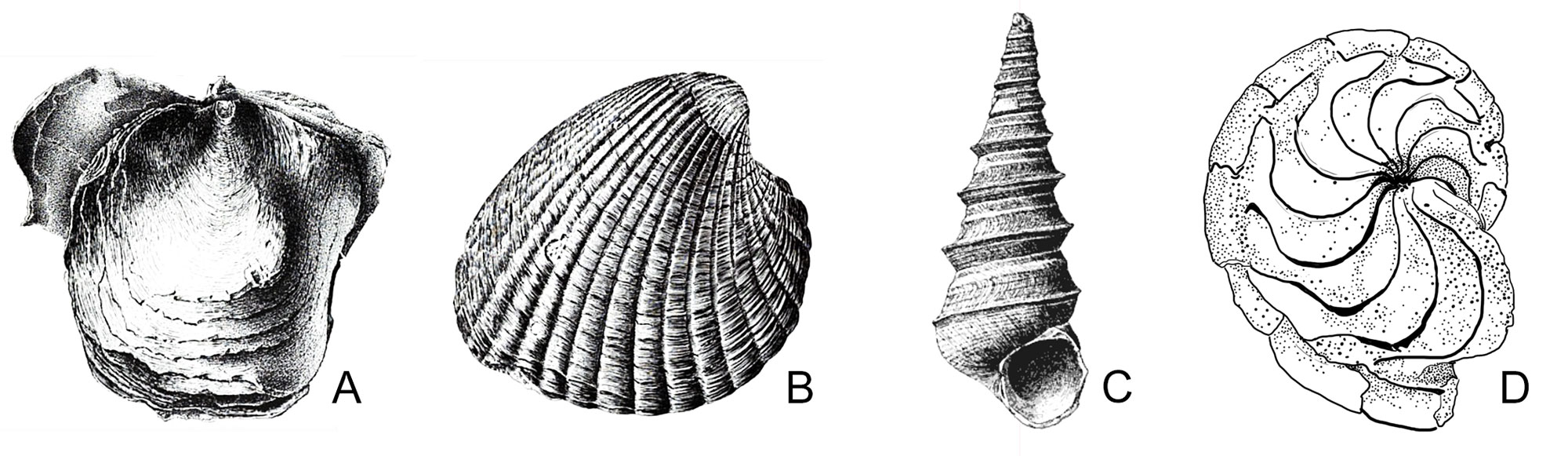

Paleogene mollusks from the Atlantic Coastal Plain. A. An oyster (Ostrea sellaeformis), Nanjemoy Formation, Virginia (width = 15 cm or 6 in). B. A clam (Venericardia planicosta var. regia), Aquia Formation, Maryland (width = 7.5 cm or 3 in). C. A marine snail (Turritella mortoni), Aquia Formation, Maryland (height = 10 cm or 4 in). D. A nautiloid cephalopod (Aturia alabamiensis), Florida (diameter = 15 cm or 6 in). Drawings A–C from Clark & Martin (1901) The Eocene Deposits of Maryland. Drawing D by Alana McGillis from a photo by the Florida Museum of Natural History.

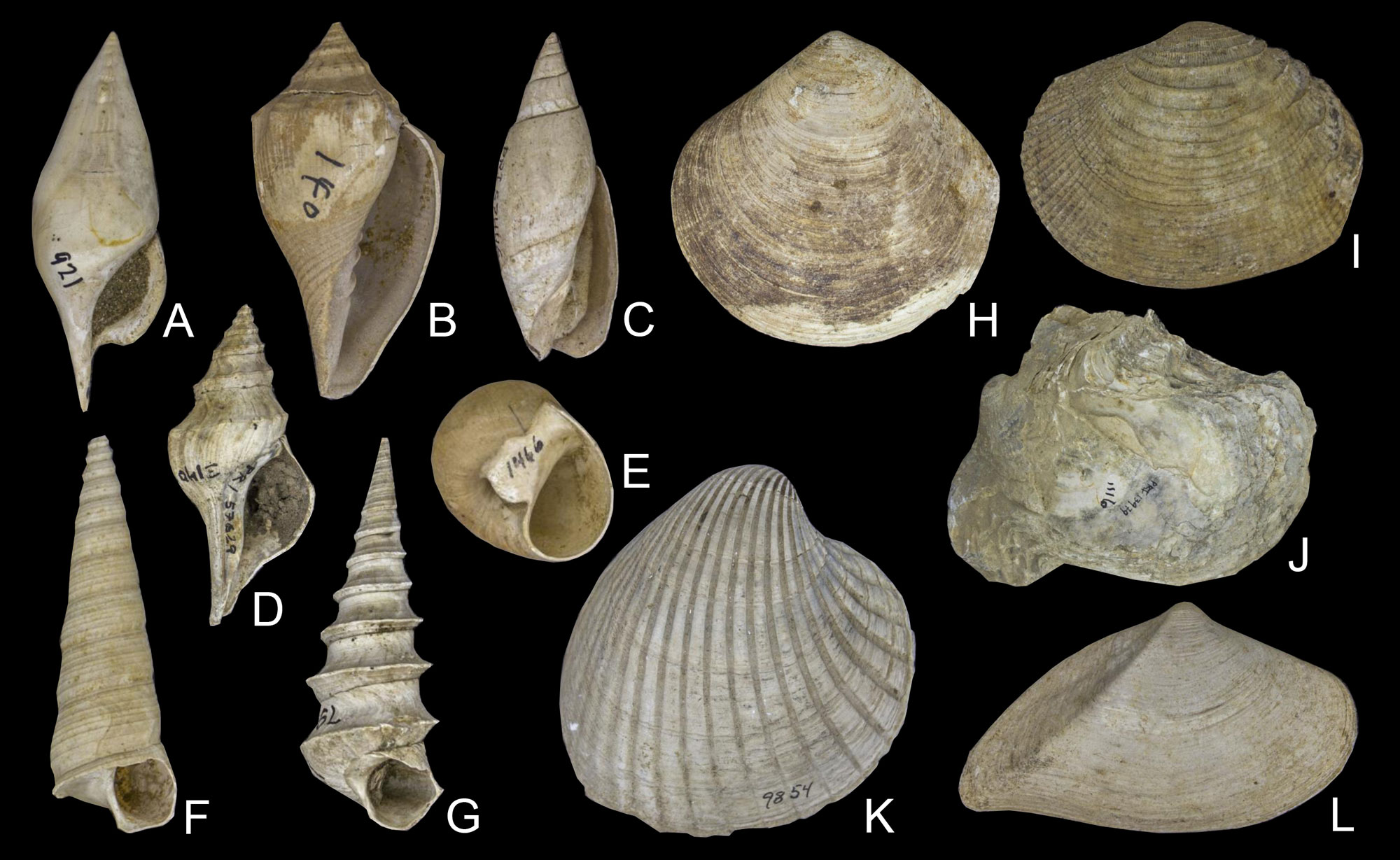

Paleogene mollusks from the Alabama and Mississippi. A–G) Gastropods; H–L) bivalves. A. Calyptraphorus velatus, late Eocene, 5 cm (2 in) tall. B. Athleta sayana, middle Eocene, 5 cm (2 in) tall. C. Agaronia alabamensis, middle Eocene, 4 cm (1.6 in) tall. D. Levifusus prepagoda, early Eocene, 5 cm (2 in) tall. E. Neverita limula, middle Eocene, 4 cm (1.6 in) tall. F. Turritella arenicola, late Eocene, 3.8 cm (1.5 in) tall. G. Turritella mortoni postmortoni, late Paleocene, 6 cm (2.4 in) tall. H. Crassatella alta, middle Eocene, 10 cm (3.9 in) wide. I. Corbis distans, middle Eocene, 4.5 cm (1.8 in) wide. J. Cubitostrea sellaeformis, middle Eocene, 10 cm (3.9 in) wide. K. Venericardia planicosta, early Eocene, 5.5 cm (2.2 in) wide. L. Crassatellites protextus, middle Eocene, 5 cm (2 in) wide. Photographs by Wade Greenberg-Brand, specimens in the collection of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York.

"35 Million Years Down the Chickasawhay | MPB" by Mississippi Public Broadcasting (YouTube)." Video highlights various Paleogene fossils.

The Gulf and Atlantic coasts of North America are passive margins, formed when the supercontinent Pangaea broke apart between 200 and 100 million years ago. The continents did not break smoothly along a straight line, but rather along an irregular line with curves pointing outward (promontories) and inward (embayments). Embayments are semi-contained environments. In the Neogene, each embayment supported its own particular types of organisms.

As the Cenozoic progressed, siliciclastic sediments eroded from the land surface and were deposited in the embayments along the Atlantic coast. Geologists and paleontologists studying the Neogene geology of the Atlantic Coastal Plain frequently study the area’s sediments and fossils one embayment at a time, then attempt to connect them together to form a larger story. Shallow marine deposits from Neogene embayments contain many abundant and diverse fossil beds. They yield mollusks (clams and snails), corals, barnacles, and many other organisms.

Florida is distinct from the rest of the coastal plain because the sediment includes more carbonate. Florida's fossil-bearing deposits vary from shelly sand in the northern and central parts of the state to reef limestone in the far southern part of the state and throughout the Florida Keys. Fossils range from Paleogene to Pleistocene in age.

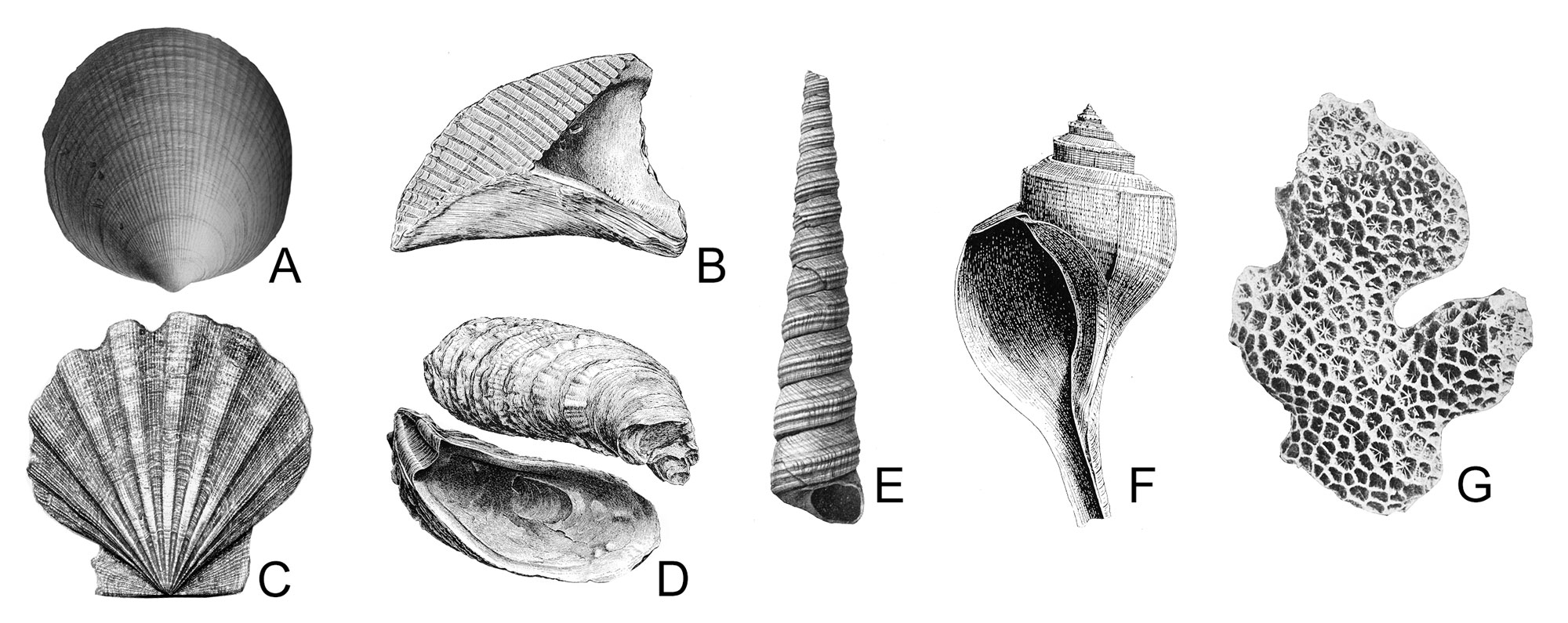

Neogene marine invertebrates from Virginia and the Carolinas. A–D) Bivalves; E, F) snails; G. corals. A. A bittersweet clam (Glycymeris americana), approximately 8.5 cm (3.5 in) wide. B. Isognomon maxillata, approximately 16 cm (6.5 in) tall/wide. C. Scallop (Chesapecten jeffersonius), approximately 12 cm (5 in) tall/wide. D. Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), approximately 16 cm (6.5 in) tall/wide. E. Marine snail (Turritella eichwaldiella), approximately 10 cm (4 in) tall/wide. F. Whelk (Busycon canaliculatum), approximately 20 cm (8 in) tall/wide. G. Scleractinian coral (Septasrea marylandica), approximately 7 cm (3 in) tall. Image sources: A and E from J.A. Gardner (1943, 1948) USGS Professional Paper 199A &199B. B, D, and F from Shattuck (1906) Maryland Geological Survey: Pliocene and Pleistocene. C by Berni Nonenmacher. G from Clark et al. (1904) Maryland Geological Survey: Miocene.

A fossil sand dollar (Encope tamiamiensis) from the Pliocene Tamiami Formation (Ochopee Limestone) of Florida. Florida Museum of Natural History specimen 22416, image from Neogene Atlas of Ancient Life of the Southeastern United States (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Pliocene-Pleistocene shell deposits in Florida. Left. Quarry face showing layers of shells. Right. Detail of shells making up the deposit, including assorted bivalves and a few snails. Photos by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

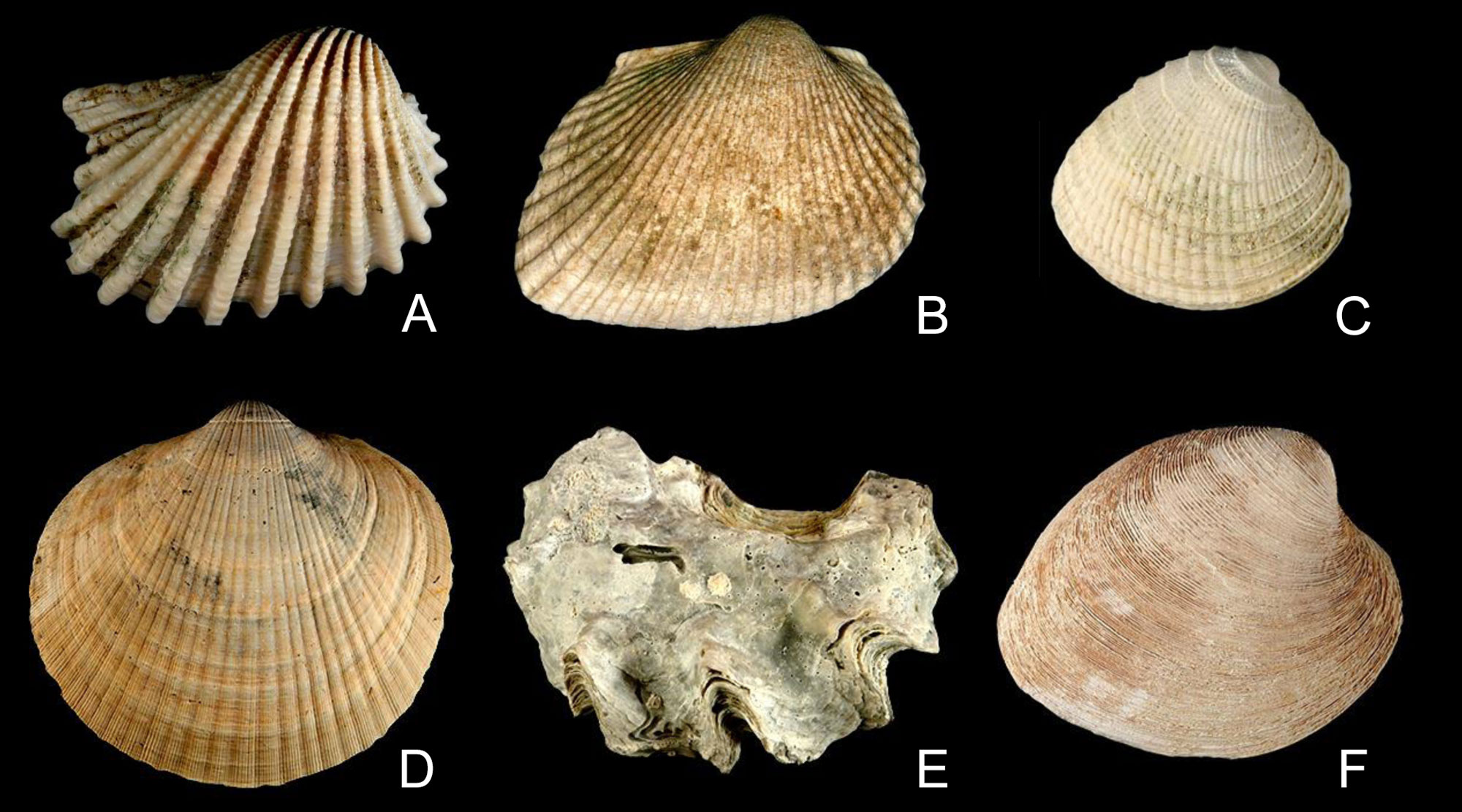

Figure 3.50: Pliocene-Pleistocene marine bivalves from Florida and the Carolinas. A. Ark clam (Anadara aequalitas), approximately 3.5 cm (1.5 in) wide. B. Ark clam (Anadara callicestosa), approximately 3 cm (1.2 in) wide. C. Chione erosa, approximately 2 cm (0.8 in) wide. D. Bittersweet clam (Glycymeris americana), approximately 5 cm (2 in) wide. E. Oyster (Undulostrea locklini), approximately 4 cm (1.8 in) wide. F. Venus clam (Mercenaria campechiensis), approximately 12 cm (7 in) wide. Images from the Neogene Atlas of Ancient Life of the Southeastern United States (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

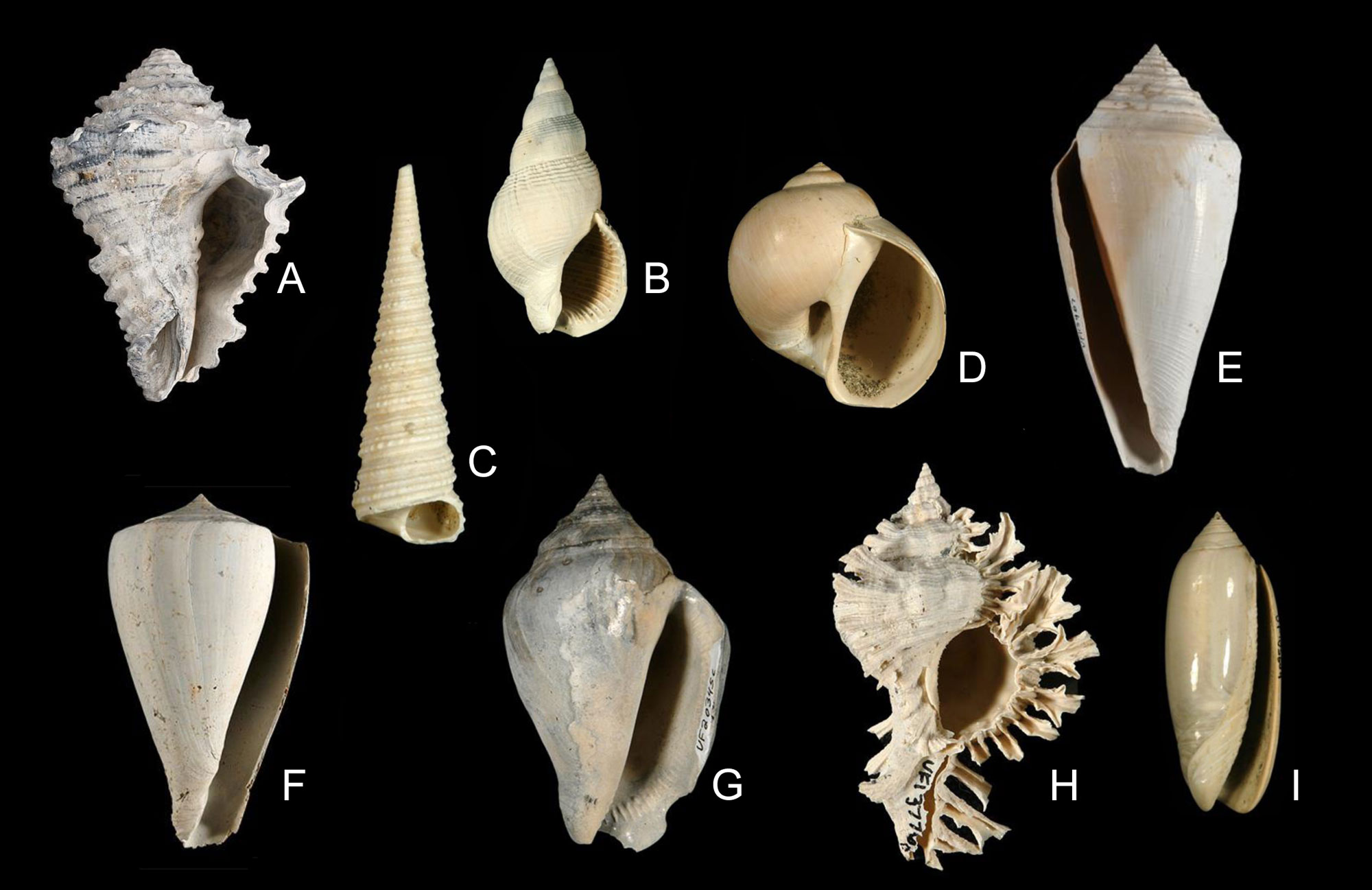

Pliocene-Pleistocene marine gastropods from Florida and the Carolinas. A. Vase snail (Vasum horridum), 8 cm (4.5 in) tall. B. Calophos wilsoni, 5 cm (2 in) tall. C. Turritella gladeensis, 5 cm (2 in) tall. D. Moon snail (Euspira sayana), 3.5 cm (1.5 in) tall. E. Cone snail (Contraconus adversarius), 10 cm (4 in) tall. F. Cone snail (Conus haytensis), 12 cm (5 in) tall. G. Conch (Strombus floridanus), 6 cm (2.5 in) tall. H. Murex snail (Chicoreus floridanus), 6 cm (2.5 in) tall. I. Olive snail (Oliva carolinensis), 5 cm (2 in) tall. Images from the Neogene Atlas of Ancient Life of the Southeastern United States (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

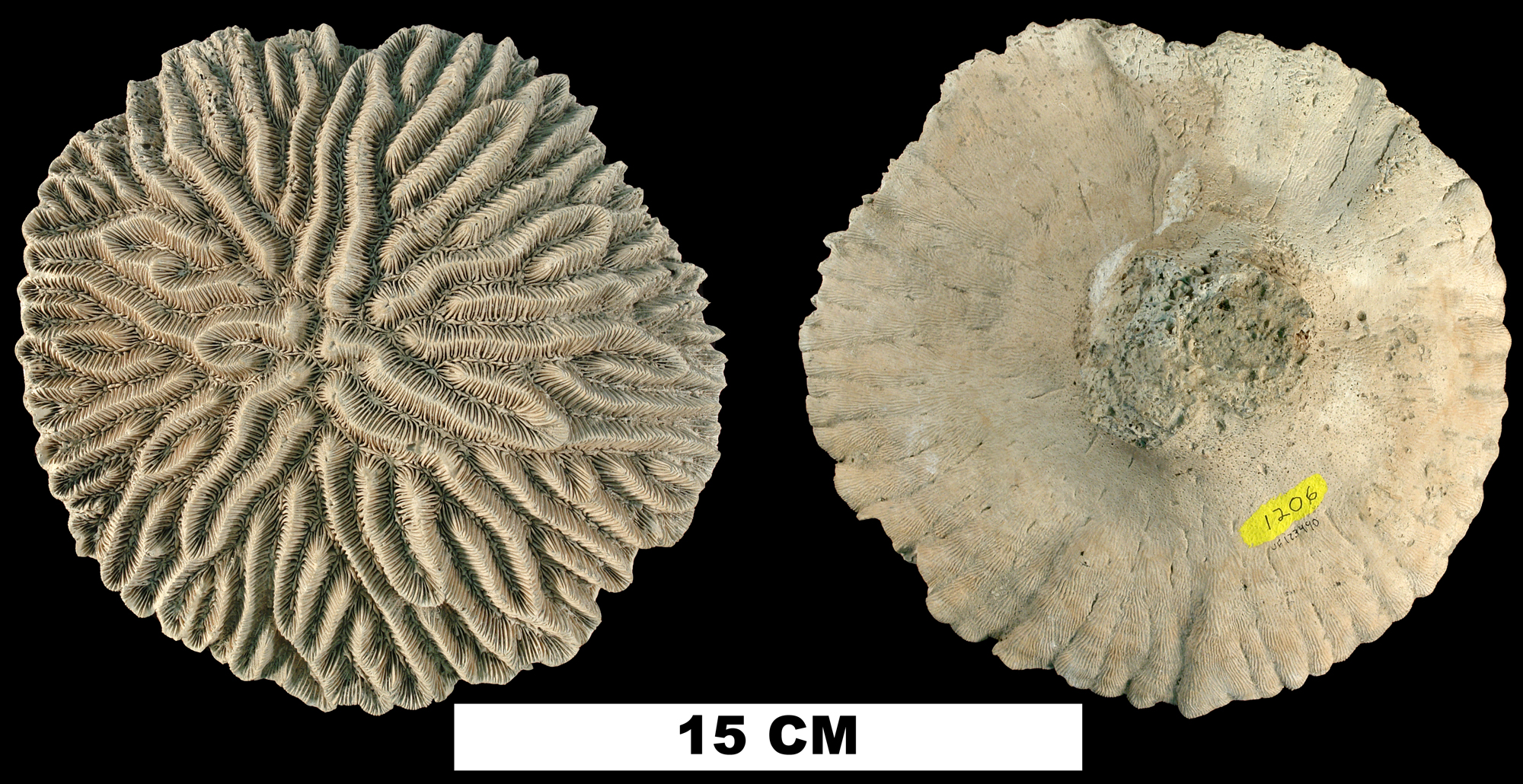

Fossil brain coral (Meandrina meandrites) from the Plio-Pleistocene of Sarasota County, Florida. Florida Museum of Natural History specimen UF 123490, image from the Neogene Atlas of Ancient Life of the Southeastern United States (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Pleistocene oyster reef at the Intracostal Waterway near Charleston, South Carolina. Photo by Steven Durham.

Fossilized coral in the Pleistocene Key Largo Limestone, exposed at the Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park in the Florida Keys. Photo by Andrielle Swaby.

Sharks and rays

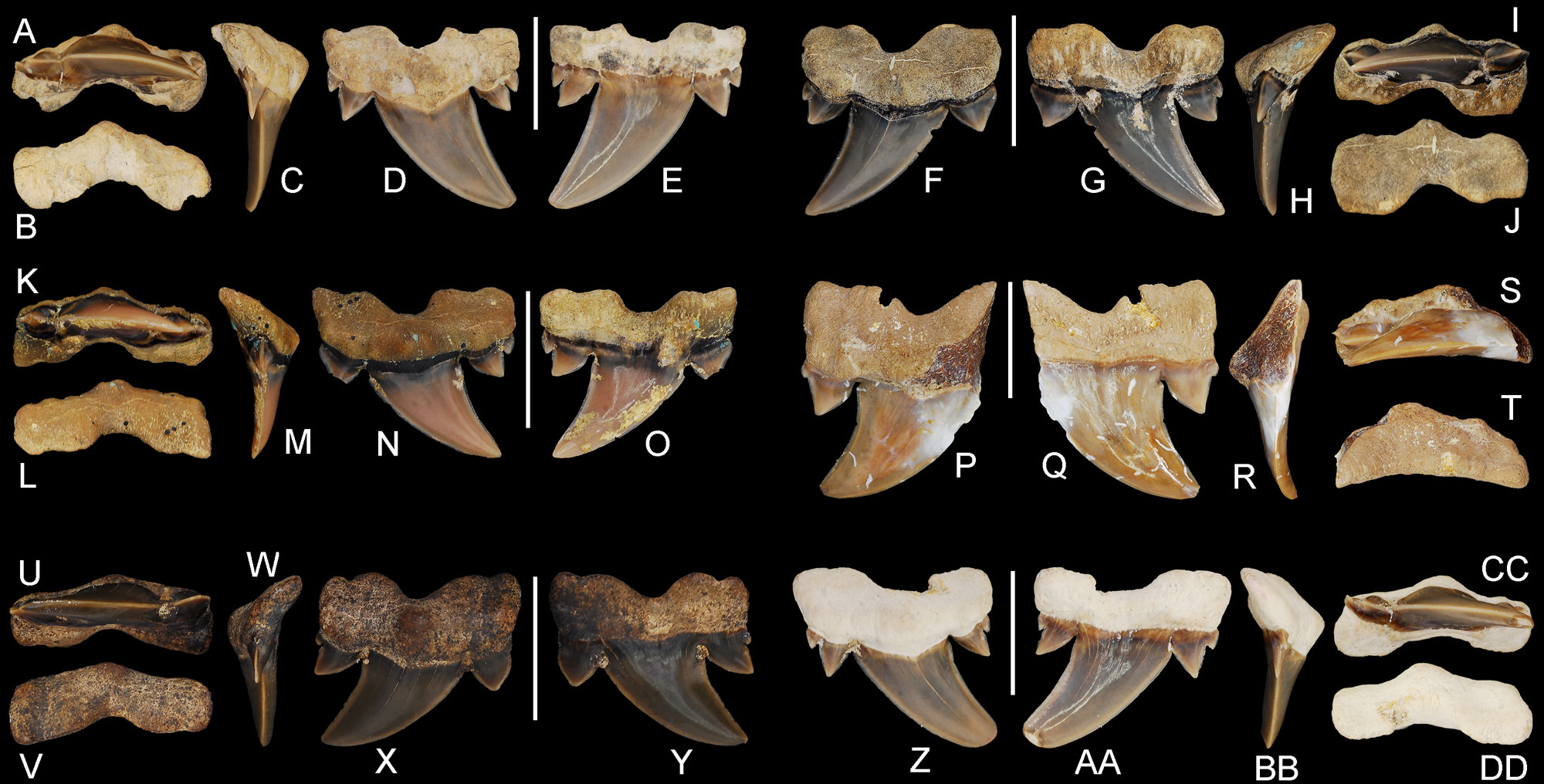

Sharks and rays have skeletons made of cartilage instead of bone, which means that their skeletons are rarely found as fossils. The teeth of sharks and rays, however, are much more resistant. They are common fossils in Cretaceous and Cenozoic sediments throughout the Coastal Plain. Shark and ray teeth are often found on beaches, where they are washed up from offshore or washed down rivers from uplands.

Sharks shed their teeth constantly, and a single individual can produce as many as 35,000 teeth during its lifetime. You can tell the difference between fossil and modern shark teeth by their color. Fossil teeth are often brown, gray, or black, whereas modern teeth are tan to white. Shark teeth come in many forms and sizes, and not all teeth in the mouth of a single individual look alike.

Teeth and reconstructed jaws of an extinct snaggletooth shark (Hemipristis serra), also called a weasel shark or requiem shark. Left: Series of teeth found on Jekyll Island, Georgia, and from dredgings near Brunswick, Georgia. Photo of United States National Museum specimen PAL297212 (CC0/public domain). Right: Reconstructed jaw with teeth in life position, late Miocene, St. Johns River, Florida, on display in the Florida Museum of Natural History. FLMNH specimen UF 156908, photo by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

The largest shark that ever lived was a species related to the modern great white shark, but much bigger. Otodus megalodon—frequently called just "megalodon"—lived in the western Atlantic Ocean from approximately 16 to 2.6 million years ago (from the middle Miocene to the late Pliocene). Megalodon is regarded as one of the largest and most powerful ocean predators that ever lived.

The fossil record of megalodon consists almost entirely of teeth, which are common fossils in the Coastal Plain. Because of the lack of body fossils, size estimates for this shark vary widely. Nevertheless, a reasonable estimate is that megalodon reached lengths of up to 18 meters (59 feet). It likely fed on large whales.

Left: A reconstruction of megalodon (Otodus megalodon) jaws with teeth. The smaller jaws to the left are of an extinct snaggletooth shark (Hemipristis serra). Photo by Jonathan R. Hendricks. Right: A megalodon tooth from South Carolina. Scale bar = 1 cm (0.4 in). Photo by Géry PARENT (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

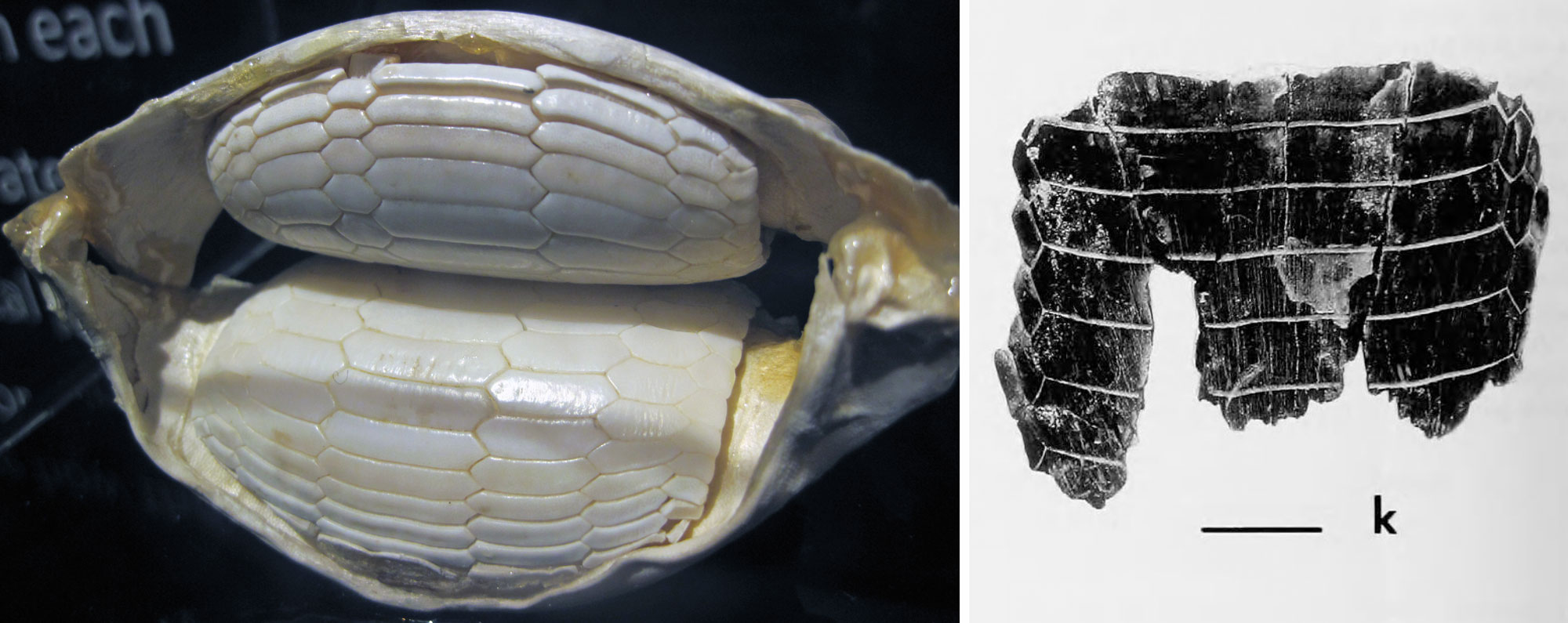

Rays and skates are close relatives of sharks and also have a fossil record that consists largely of teeth. Many ray species feed on hard-shelled prey, such as clams that they dig up out of sand bottoms. Their teeth therefore frequently have flat, ridged surfaces suitable for grinding. Ray teeth are common fossils found on beaches throughout the Coastal Plain. Sometimes, larger pieces of intact dental plates can be found.

Dental plates of rays. Left: Jaws of a modern cownose stingray (Rhinoptera bonasus) showing upper and lower dental plates used for crushing mollusks. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped). Right: Dental plate of an eagle ray (Pteromylaeus) from Miocene Pungo River Formation, Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina. Scale bar = 1 cm (0.4 in). Image from figure 12 in Purdy et al. (2001) Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 90: 71–202 (Biodiversity Heritage Library, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Marine mammals

Whales are most closely related to artiodactyls, or the even-toed hoofed mammals (for example, bison, deer, and hippopotamuses). Whales evolved from four-legged mammals that lived on land during the Eocene epoch, beginning around 55 million years ago. The early ancestors of whales were animals that resembled wolves. Fossils—especially from Egypt and Pakistan—have revealed many extinct forms that show the evolutionary steps in the remarkable transition from land-dwelling to truly aquatic animals.

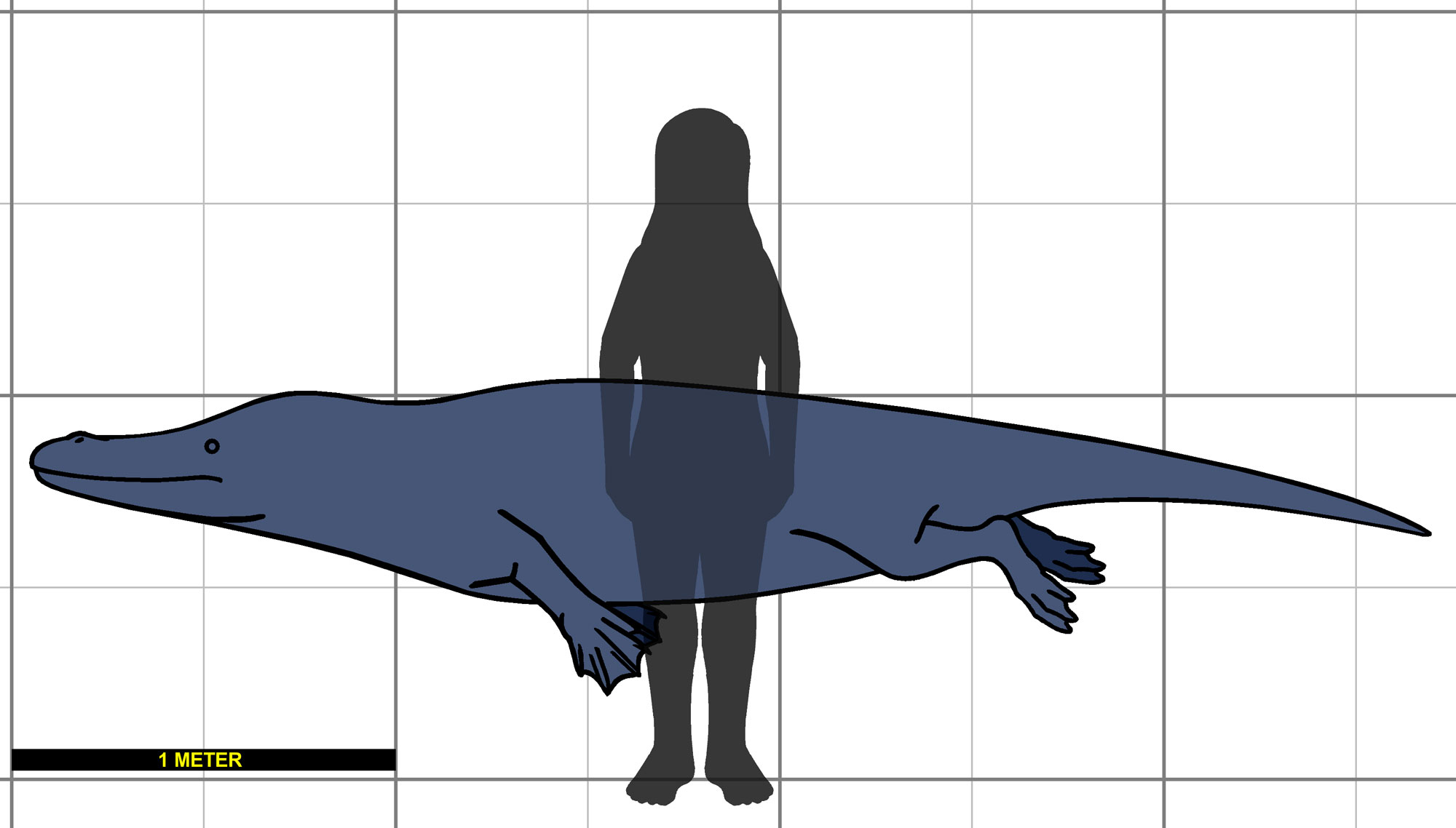

The earliest whales are from the early to middle Eocene. Relatively small forms, called protocetids (a name meaning "early whales"), have been found in Eocene sediments of the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains. The most completely known is Georgiacetus vogtlensis. It was about 3.4 m (11 ft) long and had four legs. Its skeleton shows that its rear legs probably could not have been used for walking on land. Examples of other protocetids from the Coastal Plain include Carolinacetus, Natchitochia, and Tupelocetus.

Size comparison of the middle Eocene archaeocete Georgiacetus vogtlensis to a woman about 1.75 meters tall (about 5 ft 9 in). Diagram by Conty (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Partial skull of Tupelocetus palmeri from the middle Eocene Tupelo Bay Formation of South Carolina. Model by The Charleston Museum, hosted on Sketchfab (Creative Commons-NonCommercial 4.0 International license).

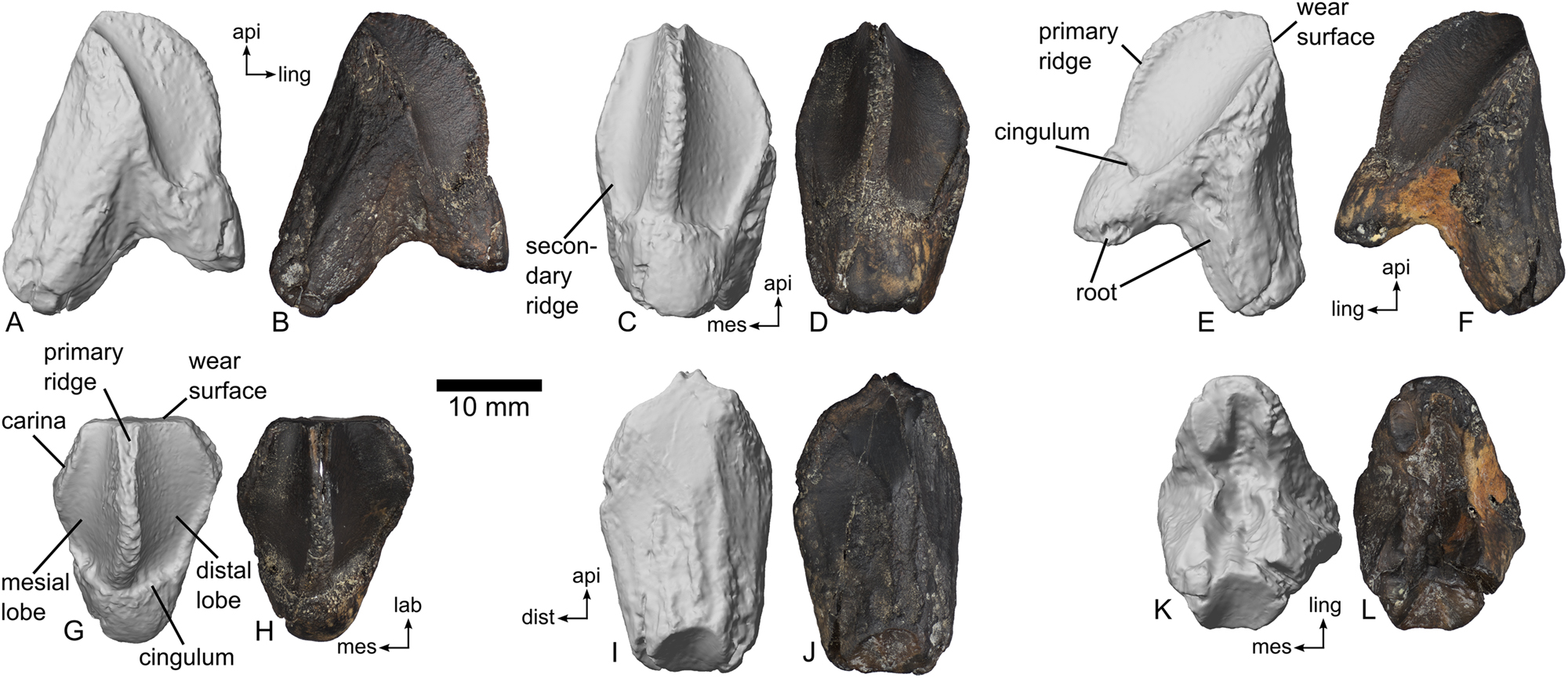

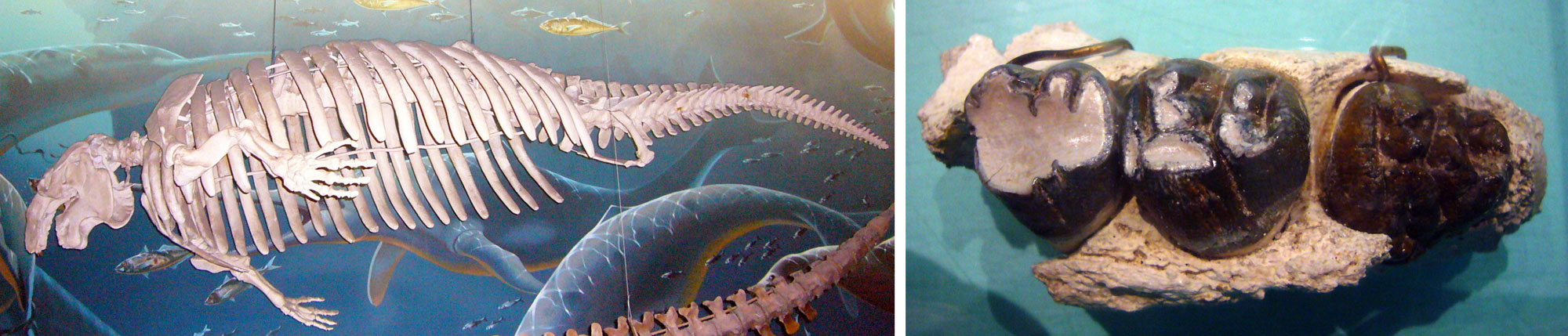

Basilosaurids (meaning "king lizards," because they were originally mistaken for reptiles) are mostly from the middle to late Eocene. These are the earliest animals that look whale-like. They could be very large—up to about 16 m (52.5 ft) long—and had elongated bodies with tiny rear legs. A small number of species lived in warm, low-latitude seas around the world. Basilosaurids became extinct in the early Oligocene.

Basilosaurids were first discovered in Eocene sediments of the Coastal Plain during the early 1800s. Examples of species found in the southeastern United States include Basilosaurus cetoides, Dorudon serratus, and Zygorhiza kochii. Their large vertebrae and multi-cusped teeth with distinctive, yolk-shaped roots can be found from Maryland to Mississippi.

An basilosaurid whale (Basilosaurus cetoides) from the Eocene of Alabama. Basilosaurus cetoides is the largest basilosaurid, reaching about 16 m (52.5 ft) long. Specimen on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. Photo of (USNM V4675) by the Smithsonian Institution (CC0/public domain).

Premolar of a basilosaurid whale from the Eocene Harleybille Formation, South Carolina. Model of CCNHM 110, Scanned by Dr. Robert Boessenecker. College of Charleston Mace Brown Museum of Natural History, hosted on Sketchfab (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license).

The two major groups of modern whales evolved from basilosaurids. The toothed whales or odontocetes (meaning "toothed whales") include dolphins, porpoises, and the sperm whale. The toothless baleen whales or mysticetes include the large, plankton-feeding whales such as humpback whales, blue whales, and right whales. Fossils of whales and dolphins can be found in Miocene and younger sediments along much of the Atlantic Coastal Plain and Gulf Coast of Florida.

Miocene sperm whale tooth, Aurora, North Carolina. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Fossil mysticete (baleen) whales from middle Miocene (ca. 14 million-year-old) Carmel Church Quarry, Calvert Formation, Virginia. Left: Cast of the skeleton of Eobalaenoptera harrisoni on display at the Virginia Museum of Natural History. The skeleton is about 6.1 m (20 ft) long. Photo from "Eobalaenoptera specimens," Updates from the Vertebrate Paleontology Lab by Alton Dooley (Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license, image cropped and resized). Right: Broken flipper of a juvenile mysticete whale. Photo from "The flipper of a baby whale," Updates from the Vertebrate Paleontology Lab by Alton Dooley (Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license, image cropped).

Manatees and dugongs belong to a group of aquatic mammals called sirenians. Sirenians are not closely related to whales. Among living animals, they are most closely related to elephants. One species of manatee lives in Florida's rivers today. Many kinds of sirenians, however, are represented by fossils found in the Coastal Plain. They are especially found in Florida, where they are the most common fossil mammal.

Fossil dugong (Metaxytherium floridanum) from the Neogene of Polk County, Florida. Left: Mounted skeleton on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. Photo of USNM PAL244477 by the Smithsonian Institution (CC0/public domain). Right: Portion of a bone with teeth. Photo of USNM PAL356680 by the Smithsonian Institution (CC0/public domain).

Cenozoic Terrestrial Fossils

Birds

Many species of Pliocene birds are found in Florida. Most of these are marine birds, like cormorants. Hundreds of skeletons of one type of cormorant (Phalacrocorax filyawi) were found together in the Pinecrest Beds of Florida. The cormorants were probably killed by a single event, and then their bodies were deposited by a storm. One possible cause for the death of so many cormorants at the same time is a red tide. A red tide is a bloom of marine algae that produce toxins capable of killing vertebrates. Cormorants are often one of the types of birds affected by modern red tides.

Bones of an extinct Pliocene species of cormorant from a shell pit near Sarasota, Florida. Hundreds of these skeletons were found in a single layer, apparently the result of a mass death due to red tide followed by deposition in a storm. Photo by Warren Allmon.

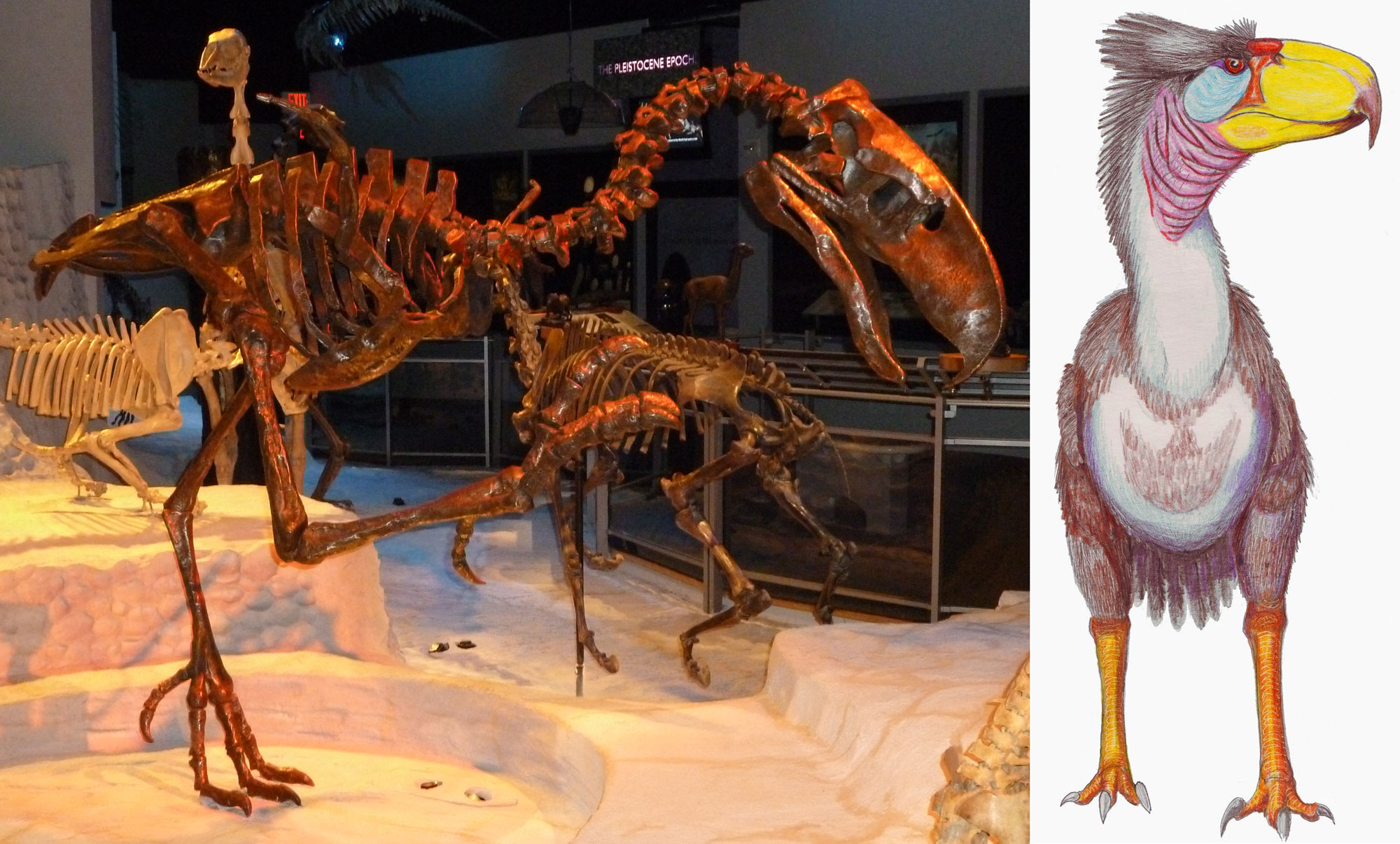

Some Pliocene birds are among the largest flightless birds that have ever lived. Waller's terror bird (Titanis walleri) is one of the largest known terror birds, an extinct group of flightless, carnivorous birds. Most terror birds lived in South America during the Cenozoic Era. Waller's terror bird was the only terror bird that lived in North America and was probably the last member of its lineage. Bones of this giant bird are found at several sites in Florida.

The North American terror bird, Titanis walleri. Left: A specimen on display at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, Florida (photo by Jonathan R. Hendricks). Right: Reconstruction of a living Titanis by Dmitry Bogdanov (Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the Creative Commons-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped).

Mammals

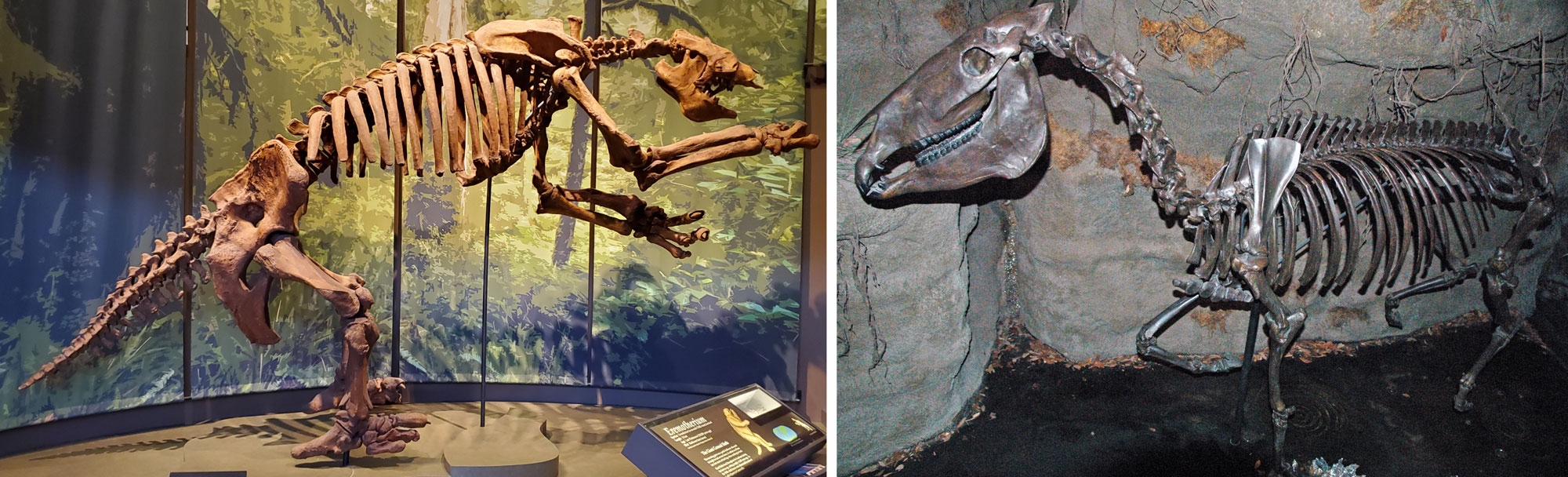

Paleogene mammals are not common in the Coastal Plain, but several species have been identified from central Mississippi. A primitive primate and an early horse are known from the late Paleocene to early Eocene and an early rhinoceros from the Oligocene. Fossils of Neogene mammals are abundant and diverse in the Coastal Plain. Florida has the richest fossil record of terrestrial mammals in the eastern United States.

Fossils of Pleistocene mammals are especially common throughout the Coastal Plain, from horse teeth on the coasts of the Carolinas to the bones of giant ground sloths, tapirs, horses, bison, and mastodons on the banks of the Mississippi River near Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Leisey Shell Pit in Hillsborough County, Florida (near Tampa Bay), has produced not only fossil shells, but was also one of the most important early Pleistocene fossil bone beds in the state (the quarry is now closed and flooded). Fossils of many species of mammals and birds have been found there, including saber-toothed cats, tapirs, horses, and llamas.

Pleistocene fossil mammals from Florida. Left: Ground sloth (Eremotherium laurillardi, cast) from Daytona Beach, Florida, on display at the Tellus Science Museum in Georgia. Photo by JJohanJackalope (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped). Right: Horse (Equus sp., cast) from Leisey Shell Pit on display at the South Florida Museum. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Among the most common Pleistocene vertebrate fossils in the Southeast are those of mastodons and mammoths. Both are common in the Southeast and elsewhere in North America during the Pleistocene. Because they had different ecological preferences, and their fossils are usually found separately. Mastodons were browsers that fed on trees and shrubs, whereas mammoths were grazers that ate grass. (Learn more on the Earth@Home Mammoth vs. Mastodon page.)

Mastodon fossils from Wakulla Springs, Florida. Left: "Herman" the mastodon at the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee, Florida. Herman was preserved underwater and collected from Wakulla Springs in the 1930s, in an expedition led by Herman Gunter. Photo by Mark Nicolou (Florida Memory, image DG003430, public domain). Top right: Mastodon skull from Wakulla Springs with ruler for scale, 1931. Photo from Florida Memory (image GE1394, public domain). Bottom right: George Christie, Herman Gunther, Gerald Mungo Ponton, and J. Clarence Simpson (order in image unknown) with fossil mastodon bones collected from Wakulla Springs in 1931. Photo from Florida Memory (image GE1318, public domain).

Plants

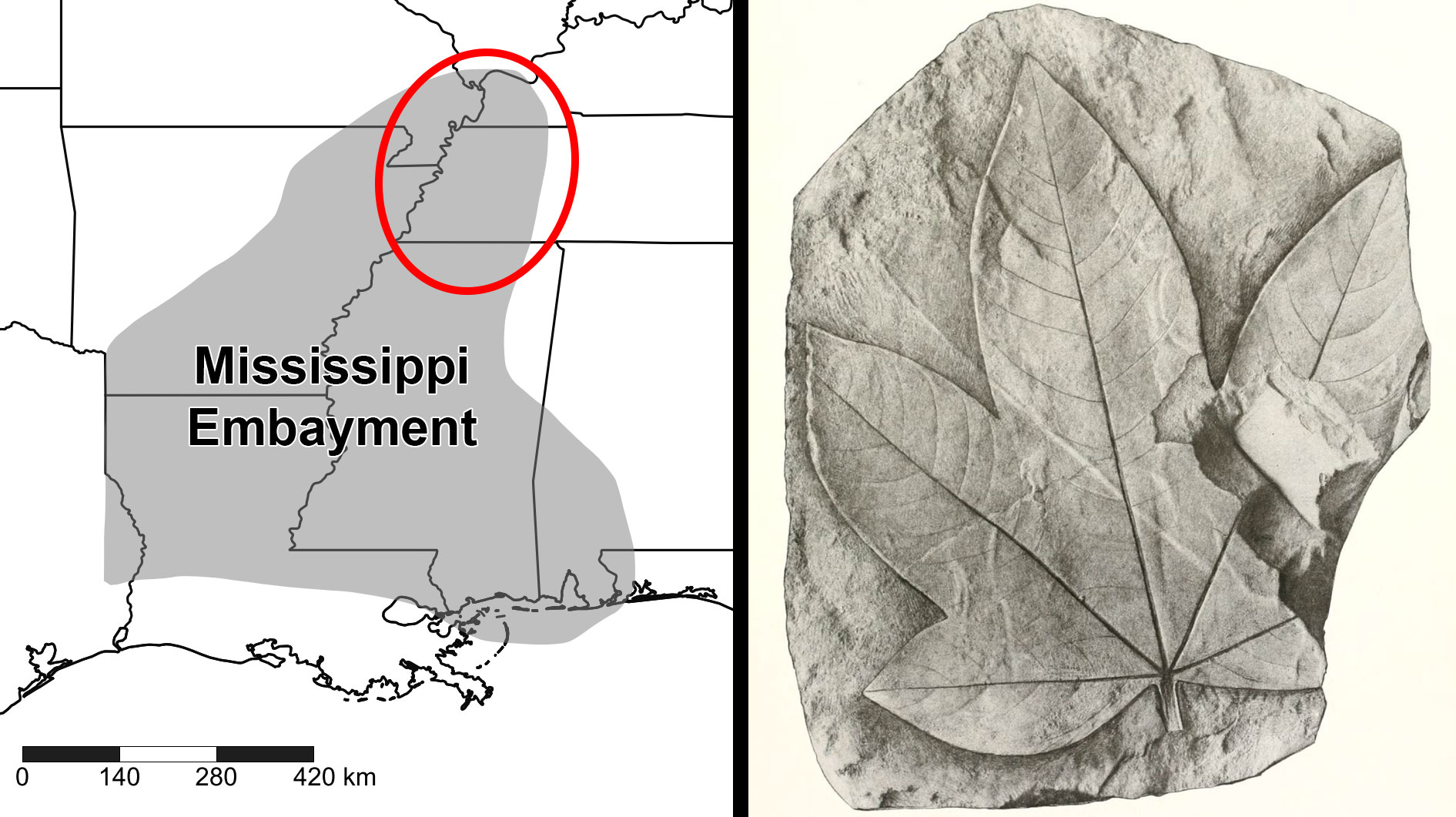

Cenozoic plant fossils are surprisingly common across the Coastal Plain. Fossil leaves are especially abundant in deposits of early Eocene age in the Mississippi Embayment, which includes parts of Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Some of the most well-known Eocene plants come from clay pits in Kentucky and eastern Tennessee. These fossils are from the Claiborne Group. They include not only leaves, but also flowers and fruits.

Left: Map showing the approximate extent of the Mississippi Embayment in the Coastal Plain. The circled area shows the region of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi where Paleogene plants are found at well-known sites like Puryear and Warman. (Map by Elizabeth J. Hermsen, created with SimpleMappr, modified in Photoshop). Right: Eocene leaf of Sterculia puryearensis from the Puryear clay pit, Cockfield Formation, Claiborne Group, Tennessee. Plate 73 from Berry (1916) USGS Professional Paper 91.

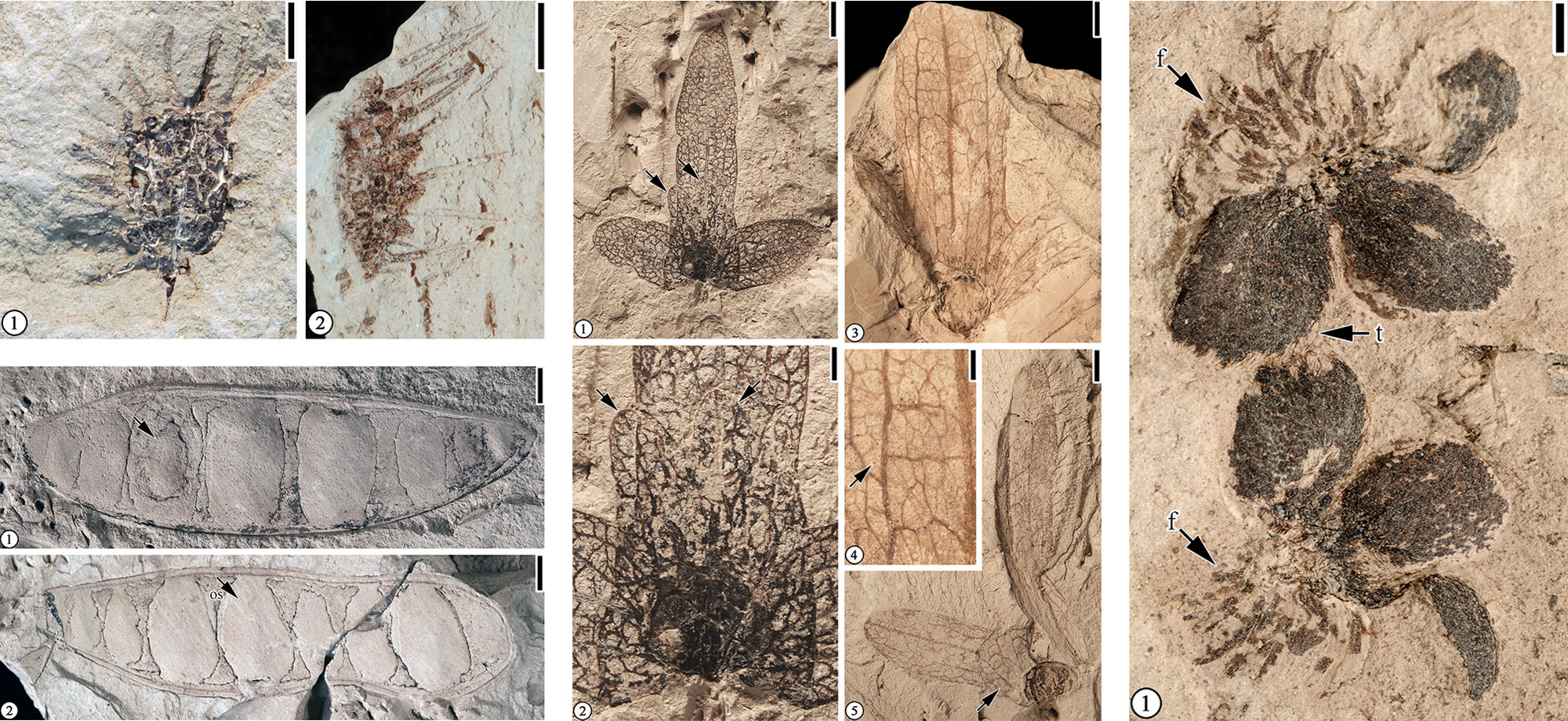

Eocene fruits and flowers from the Puryear Claypit, Cockfield Formation (Claiborne Group), Tennessee. Upper left: Fruits of hornwort (Ceratophyllum muricatum), an aquatic plant. Scale bars = 2 mm. Bottom left: Legume fruits. Scale bars = 4 mm. Center: Winged fruits of Palaeocarya puryearensis, an extinct member of the walnut family. Scale bars = 3 mm (1, 3, 5), 1 mm (2, 4). Right: Flowers of Eoceltis dilcheri, a member of the elm family. Scale bar = 1 mm. All images from Na et al. (2020) Palaeontologia Electronica 23(3):a49 (Creative Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license). Images modified from originals (resizing, cropping).

Plant fossils occasionally form localized deposits of brown coal, called lignite. Petrified wood also occurs in a number of places in the Coastal Plain. Mississippi even has its own petrified forest in the town of Flora. The forest is privately owned but is open to the public as a tourist attraction. It is about 36 million years old, or near the Eocene-Oligocene boundary in age.

Paleogene petrified logs at the Mississippi Petrified Forest. Photo by amanderson2 (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Neogene plant fossils are scattered across the Coastal Plain, although only a few major plant fossil deposits have been described. The Hattiesburg flora from Mississippi and the Alum Bluff flora from the Florida panhandle are Miocene in age. The Pliocene Citronelle flora is known from several different locations in the Citronelle Formation of Alabama and Florida. Many of the plants in these Neogene floras still inhabit the United States, although a few types of plants are found only in Eurasia today. Examples include the wingnuts (Pterocarya), hong teng (Sargentodoxa), and crown of thorns (Paliurus).

Miocene plant fossils from the Bouie River locality, Hattiesburg Formation, Mississippi. 1–3. Oak leaves (Quercus). 4. Walnut (Juglans). 5–6. Hickory nut (Carya). 7. Hong teng seed (Sargentodoxa). Scale bars = 5 mm (0.2 in). All images from figure 6 in McNair et al. (2019) Palaeontologia Electronica 22.2.40A: 29 pages (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license). Image modified from original (reorganized, cropped).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central U.S.: Fossils of the Coastal Plain (continues coverage of the Gulf Coastal Plain in Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-cp/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/

Neogene Atlas of Ancient Life (covers the Neogene of the Coastal Plain in Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida): Southeastern United States: https://neogeneatlas.net/