Snapshot: Overview of the topography and landforms of the Coastal Plain region of the southeastern United States, including the Atlantic Coastal Plain, the Florida Platform, and the Gulf Coastal Plain and Mississippi Embayment.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction, The Atlantic Coastal Plain, The Florida Platform, The Gulf Coastal Plain and Mississippi Embayment.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Southeastern US" by Michael A. Gibson and Andrielle Swaby, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S., 2nd ed., edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated February 25, 2022.

Image above: Satellite image of the Florida Keys from space. Image by NASA (Visible Earth; public domain).

Introduction

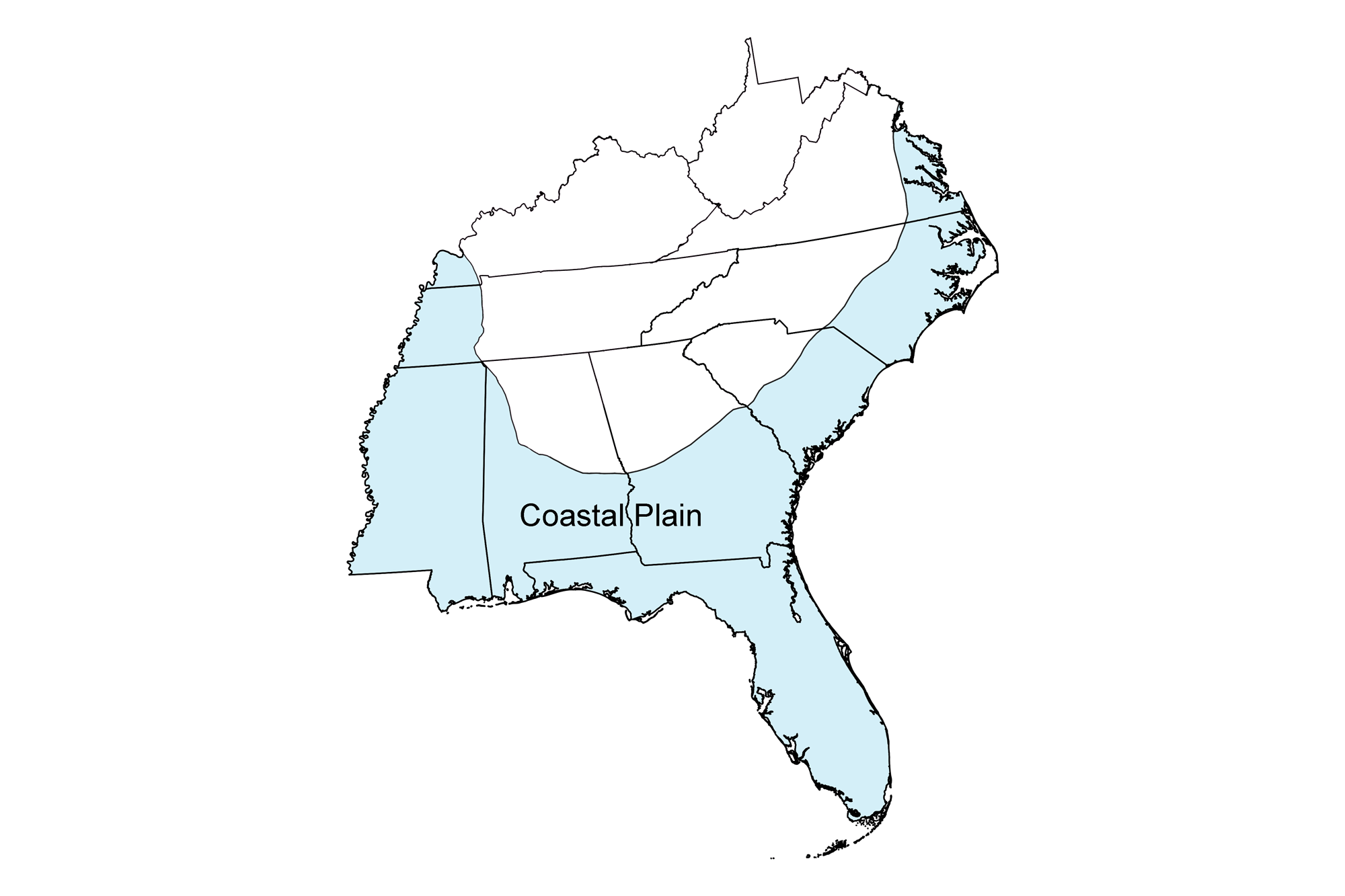

The entire eastern and southern margin of the Southeast consists of relatively flat to gently-sloped loose gravel, sand, and clay sediments of Mesozoic and Cenozoic age. The Coastal Plain begins at the Fall Line, where slow erosion of the Piedmont's crystalline rocks forms numerous waterfalls and rapids, and extends east to the Atlantic Ocean and south to the Gulf of Mexico. Rivers flowing east out of the Piedmont over the Fall Line quickly deepen and widen as they erode the Coastal Plain's looser materials. The region's sediments form a thickening "clastic wedge" nearly 15,000 meters (49,000 feet) thick, which extends below sea level to become the continental shelf-slope-rise system. Most of the Atlantic states subdivide the Coastal Plain into an upper hilly and dissected plain and a flatter, sloping lower plain.

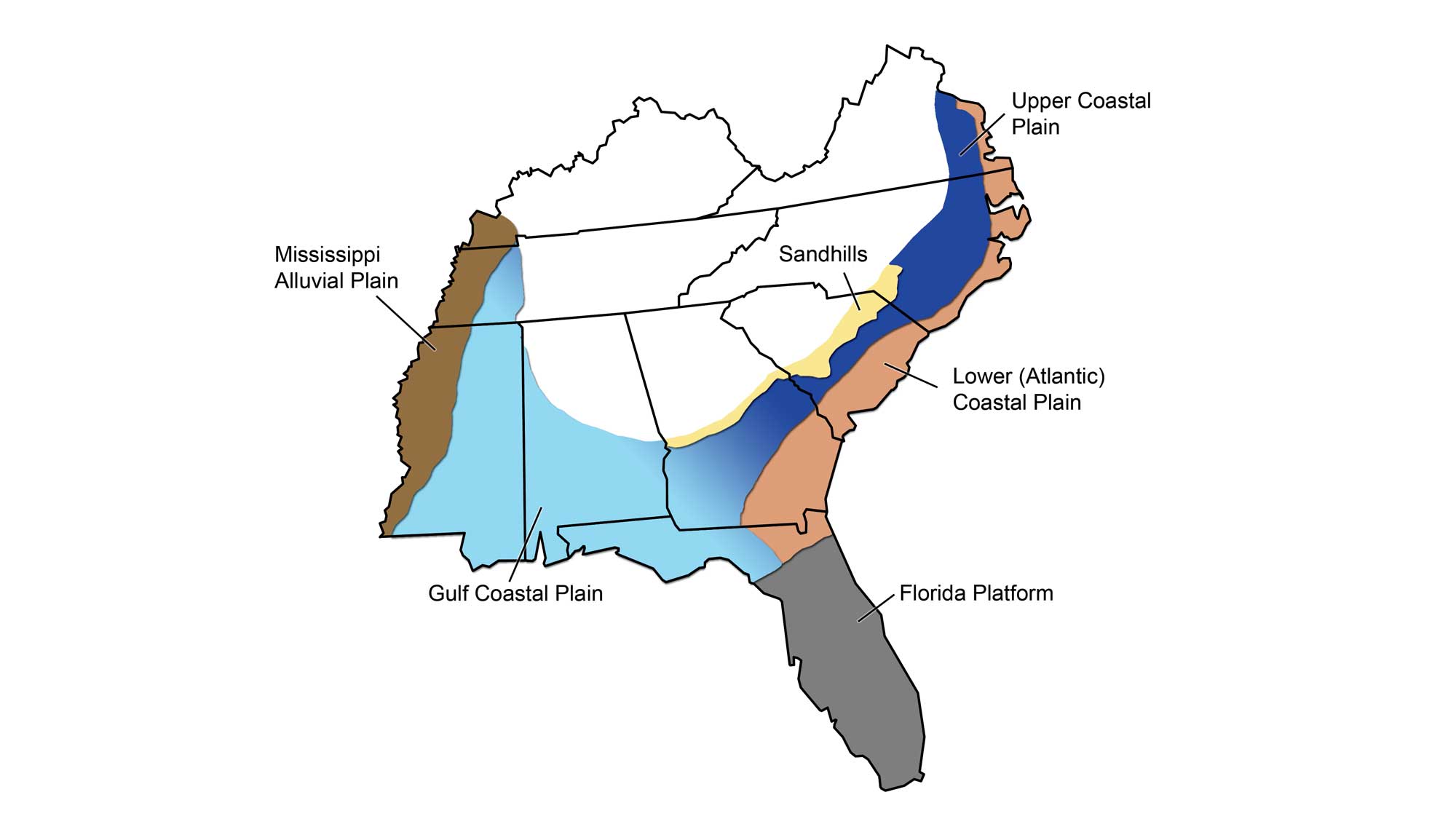

Physiographic subdivisions of the Coastal Plain region. Wade Greenburg-Brand; modified for the Earth@Home project.

From the Atlantic Seaboard, the Coastal Plain wraps around into the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf Coastal Plain, and up into the Mississippi Embayment at the region's western margin. To the south, the Florida peninsula represents the carbonate Florida Platform.

The Atlantic Coastal Plain

Rivers and Bays

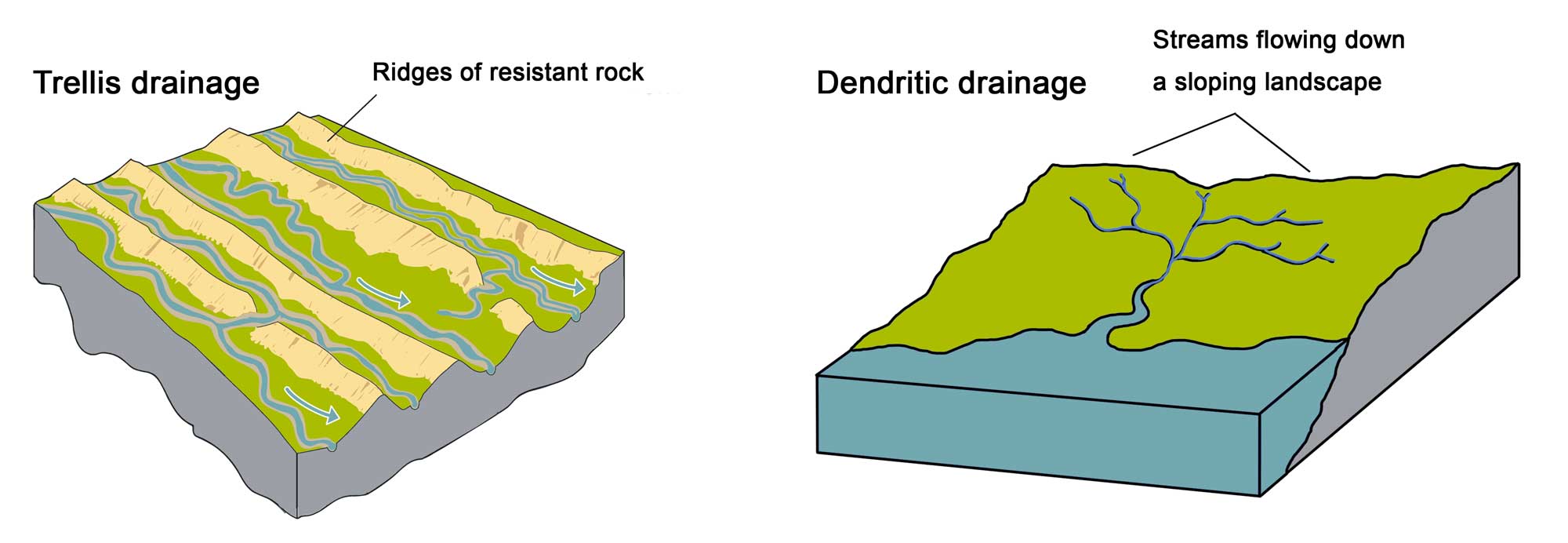

The interior portions of the Coastal Plain are topographically broad uplands displaying low slopes toward the sea and gentle drainage divides with mostly dendritic drainage structures.

Comparison of trellis (left) and dendritic (right) drainage patterns. Image on left by Marie Regipa; image on right by Wade Greenberg-Brand; images modified for the Earth@Home project.

These rivers, such as the Chattahoochee in Georgia, have their headwaters in the Blue Ridge and Piedmont region.

From its source in Georgia's Blue Ridge Mountains, the Chattahoochee River flows southwest to form the southern half of the Alabama/Georgia state line before entering the Florida Panhandle. The river is shown here at Norcross, Georgia (near Atlanta). Photograph by Mike Gonzalez (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

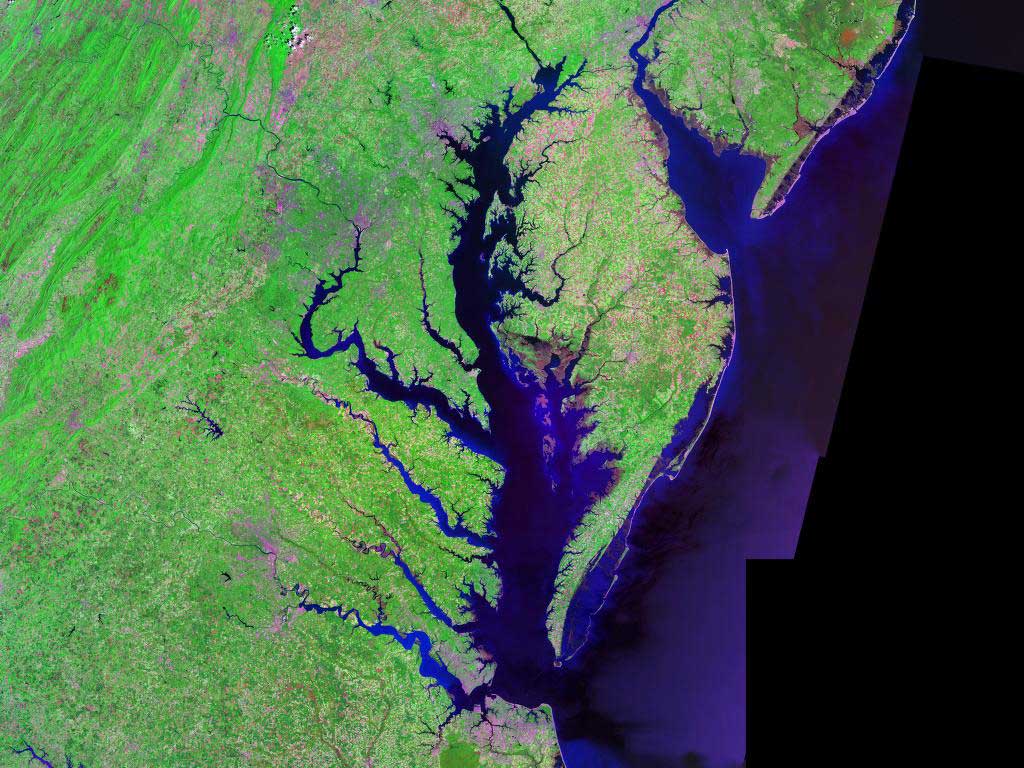

Where stream erosion has incised more deeply—drainage slopes may show elevations of 20 to 75 meters (60 to 250 feet). Closer to the coast, relief is much more subdued, with elevations ranging from 0 to 20 meters (0 to 60 feet). Coastal boundaries become very irregular with multiple drowned river valleys—broad, deeply indented coastal inlets that represent the original course of a river. In Virginia, the eastward-flowing rivers crossing the Piedmont (e.g., Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James rivers) become tidal estuaries that empty into the Chesapeake Bay, itself a uniquely large drowned river, which then empties into the Atlantic Ocean.

Satellite image of Chesapeake Bay on Virginia's Atlantic coast. Image by NASA (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

For example, the Susquehanna River flows through the Chesapeake lowland region for more than 90 kilometers (56 miles) before emptying into the modern Chesapeake Bay, which was submerged about 5000 to 6000 years ago with the drowning of the Susquehanna's lower reaches.

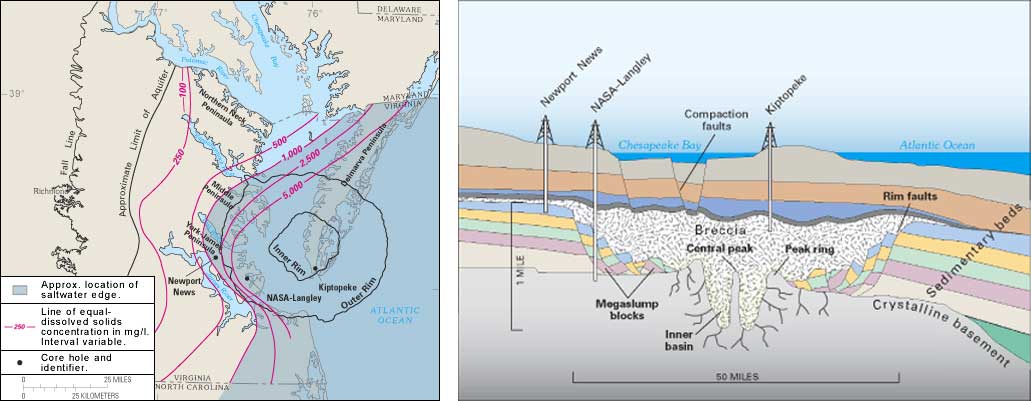

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay owes its original existence to an impact event that occurred 35 million years ago. The circular Chesapeake Bay Crater (over 85 kilometers [53 miles] in diameter and 1.3 kilometers [0.8 miles] deep) is not currently visible at the surface because it was modified by later processes of erosion and deposition; however, the deep depression of the impact topographically influenced the drainages that produced the present-day Chesapeake Bay—explaining why it is the only drowned river of its size on the East Coast.

Left: Boundaries of the Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater. Left: Geological cross section of the crater. Both images from the USGS (public domain).

Terraces and Scraps

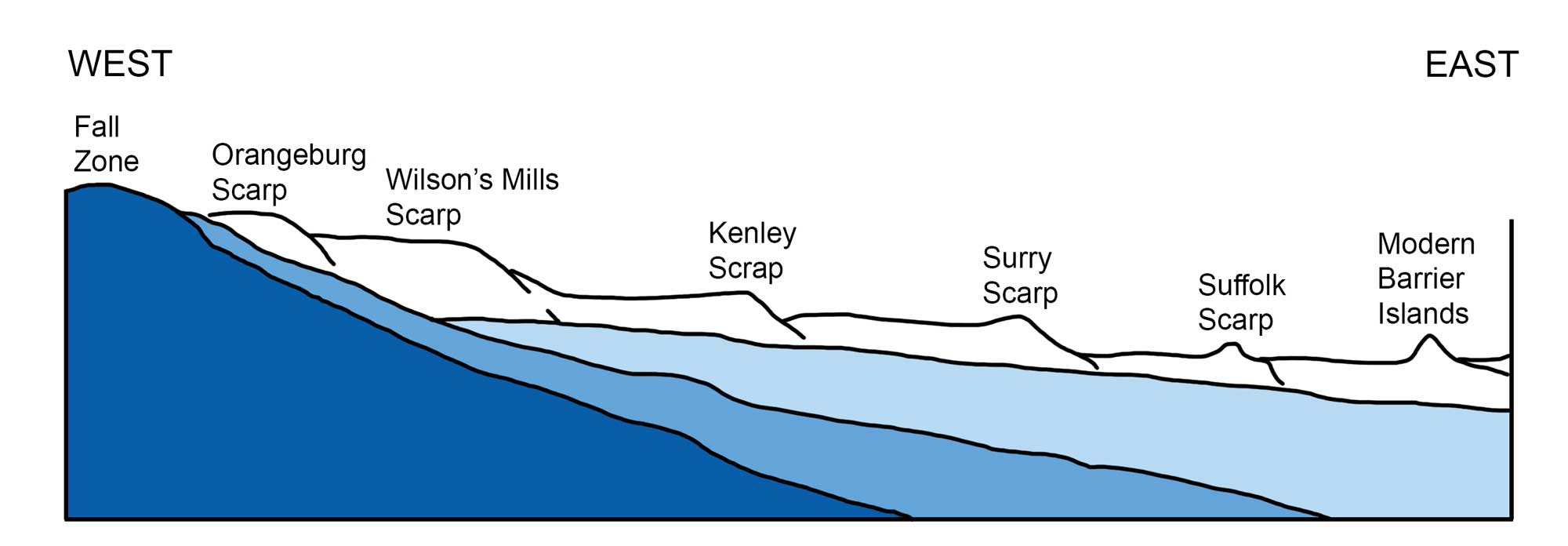

Several drops in sea level since the last glacial maximum have resulted in topography that preserves relict shorelines traceable into the Atlantic (and Gulf) coasts. In fact, much of the currently drowned continental shelf was emergent low coastal plain during the last ice age. Relatively low, wide, and flat terraces stairstep downward in elevation toward the coast.

Narrow steps that mark former shorelines, known as scarps, are recognized by narrow contour lines traceable at the same elevation throughout the Southeast. Higher terraces to the west represent older and higher shorelines formed when sea level was higher, during interglacial periods; lower terraces formed when sea level dropped during glaciations.

The scarps and intervening terraces of North Carolina's Coastal Plain. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, modified for the Earth@Home project. Adapted from image by Beyer, Fred (1991), North Carolina: The Years Before Man, Carolina Academic Press, Durham, NC.

In South Carolina, seven terrace-scarp pairs stairstep the topography of the lower Coastal Plain, representing seven cycles of the receding ocean levels. These seven sea level shifts are traceable along the Atlantic seaboard and include two that occurred during the Pliocene epoch, followed by four during the Pleistocene epoch and the current Holocene shift. For example, the Orangeburg Scarp, extending from central North Carolina to northeast Florida, formed from wave erosion during an interval of high sea level during the mid- to late Pliocene (3.5–2.5 million years ago).

The Sandhills

The Sandhills, a strip of ancient beach dunes, are a distinctive feature of the Upper Coastal Plain and stretch from North Carolina into Georgia along the Fall Line. This formation of broad flat ridges and rolling hills formed from a combination of fluvial Cretaceous sediments deposited around 90 million years ago by meandering streams, and marine sediments deposited about 45 million years ago during a sea level highstand.

The Sandhills of Peachtree Rock Preserve in South Carolina support a scrubby forest of longleaf pine and oak. Photograph by "Hunter Desportes" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

These sandy sediments are highly permeable, easily absorbing precipitation; as a result, the Sandhills are not highly eroded. A portion of South Carolina's peach industry thrives in the area's sandy soils.

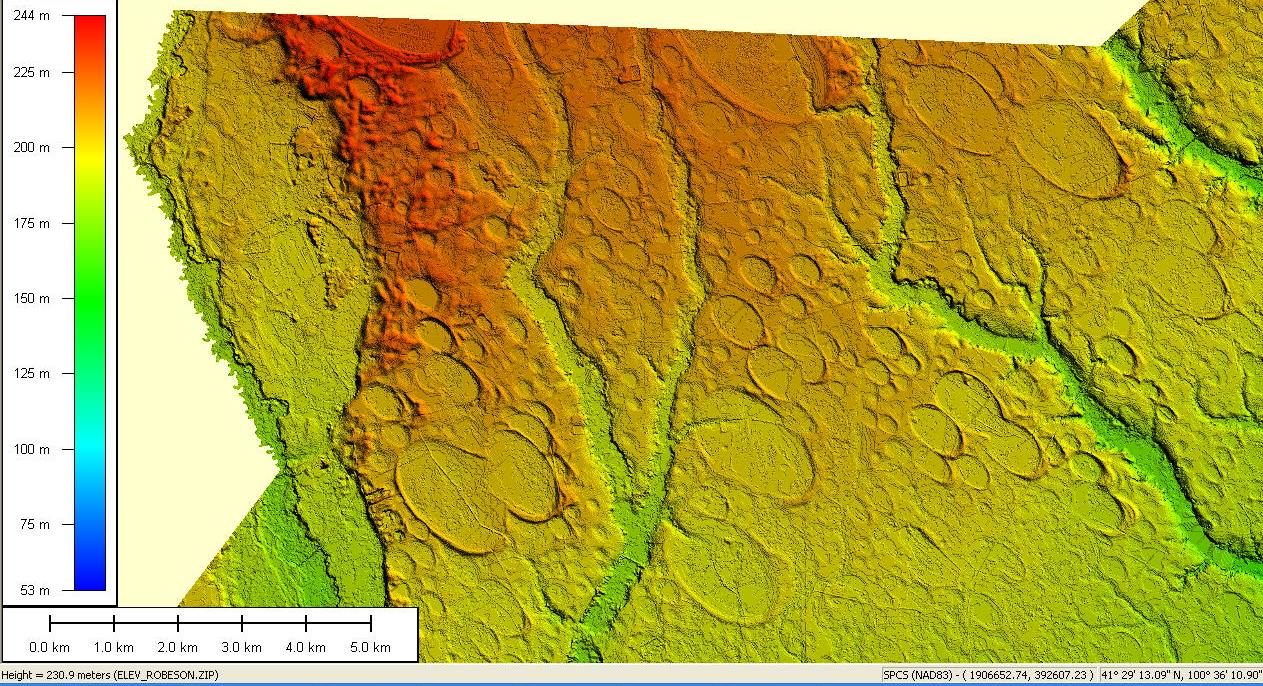

The Carolina Bays

An unusual topographic feature of the Lower Coastal Plain, best seen in North and South Carolina, are the Carolina Bays. These are not actually marine coastal bays, but large, elliptical inland depressions whose long axes are aligned in the same general northwest to southeast direction.

Digital elevation map data collected by remote sensing LIDAR technology reveals the presence of hundreds of Carolina Bays in a 600-square-kilometer (230-square-mile) segment centered on Robeson County, North Carolina. Image by "Swampmerchant" (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

Aerial view of more than a dozen Carolina Bays in southeastern North Carolina. Image by "Swampmerchant" (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

The bays are often difficult to visualize from land, as their rims can be only a few centimeters in height. They can be as large as thousands of acres, and nearly 500,000 of them occupy the Atlantic Coastal Plain. They are visible on maps and photographs from space, especially where lakes, boggy swamps, or savannahs occupy the bays. Several theories have been proposed for the Bays' formation, including sea currents, groundwater seepage, aeolian processes, and even extraterrestrial impact.

Barrier Islands and the Outer Banks

Extending from the eastern Shore of Virginia along the coasts of North and South Carolina, Georgia, and portions of Florida is an extensive barrier island complex. Locally, the shapes of barrier islands can change from submergent coastlines protected by relatively linear, thin ribbons of island (Outer Banks, North Carolina) to beach-fronted mainlands with smaller barriers (South Carolina, Georgia, and south into Florida). Along the Gulf Coast, barrier islands also extend to the Mississippi River Delta. Barrier islands of the Atlantic region are zoned ribbons of mostly quartz sand, dynamically sculpted into beaches, dune fields (e.g., Kitty Hawk, North Carolina), marshes, and protected sounds.

In North Carolina, the linear stretches of the Outer Banks separate the Atlantic Ocean from the much more irregularly shaped marshes and protected bays of Pamlico and Albemarle sounds. Thanks to the protection of the Outer Banks, Pamlico and Albemarle sounds have the distinction of being the two largest "landlocked" bays on the East Coast. At Capes Hatteras, Lookout, and Fear, the direction of the Outer Banks shift, making sharp, prominent turns. Storm systems and shifting sand bars have caused hundreds of shipwrecks, and North Carolina's barrier islands are sometimes called "The Graveyard of the Atlantic."

Left: Satellite photo of North Carolina's Outer Banks; image by NASA (Wikimedia Commons; public domain). Right: Aerial view of the Outer Banks of North Carolina; image by NOAA (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

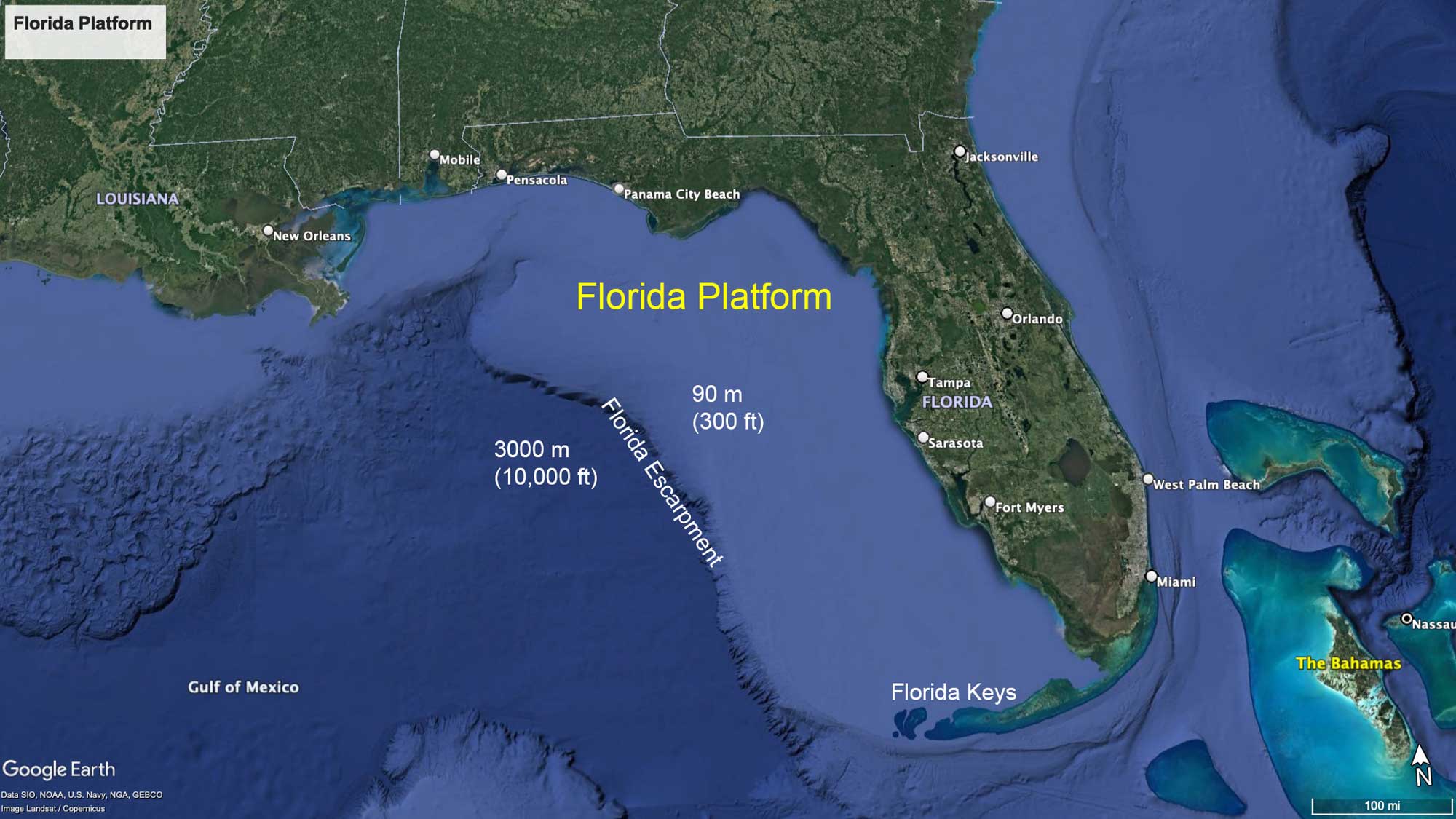

The Florida Platform

The majority of Florida is situated much farther south than the rest of the Coastal Plain, stretching toward the subtropics. While most topography in northern Florida and the Florida Panhandle resembles that of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts (especially in terms of terracing), middle peninsular and southern Florida is a relatively flat carbonate platform, originally formed underwater and now exposed barely above sea level.

The Florida Platform divides the Gulf of Mexico from the Atlantic Ocean, and on its western margin (the Florida Escarpment) steep undersea cliffs drop off sharply to over 3000 meters (10,000 feet) in depth. The terrestrial Florida peninsula is located toward the eastern side of the platform, which terminates as few as 5 to 6.5 kilometers (3 to 4 miles) from the land's edge. The Florida Platform's carbonate rocks have easily eroded to produce a flat, subdued topography throughout central and southern Florida. The platform's bedrock is overlain by a layer of porous karst limestone, which has eroded to produce extensive systems of caves, sinkholes, and springs.

Karst and Aquifers

Florida's karst contains the most productive aquifer in the U.S., called the Floridian Aquifer. It is composed largely of Paleocene and Miocene limestone. This aquifer underlies all of Florida, as well as parts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. In the northwest part of peninsular Florida, between Tampa Bay and Tallahassee, the aquifer is unconfined, meaning water can flow directly between it and the surface. Elsewhere, it is confined beneath a less permeable layer, and thus under pressure. One result of this is that Florida has numerous springs (more than 700, including large ones, such as Wakulla Springs in Wakulla County, and Weeki Wachee Springs in Hernando County), which are natural artesian outflows from the Floridian Aquifer.

"Learn How An Artesian Well Works at Aiken State Park! [South Carolina]" by SCStateParks (YouTube).

Water temperatures in these springs are usually relatively constant (generally around 24°C [75°F]), and as a result some of them provide unique habitat for several species of plants and animals, including manatees.

A Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus) at Three Sisters Springs, Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge), Florida. Photograph by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Lake Okeechobee and the Florida Everglades

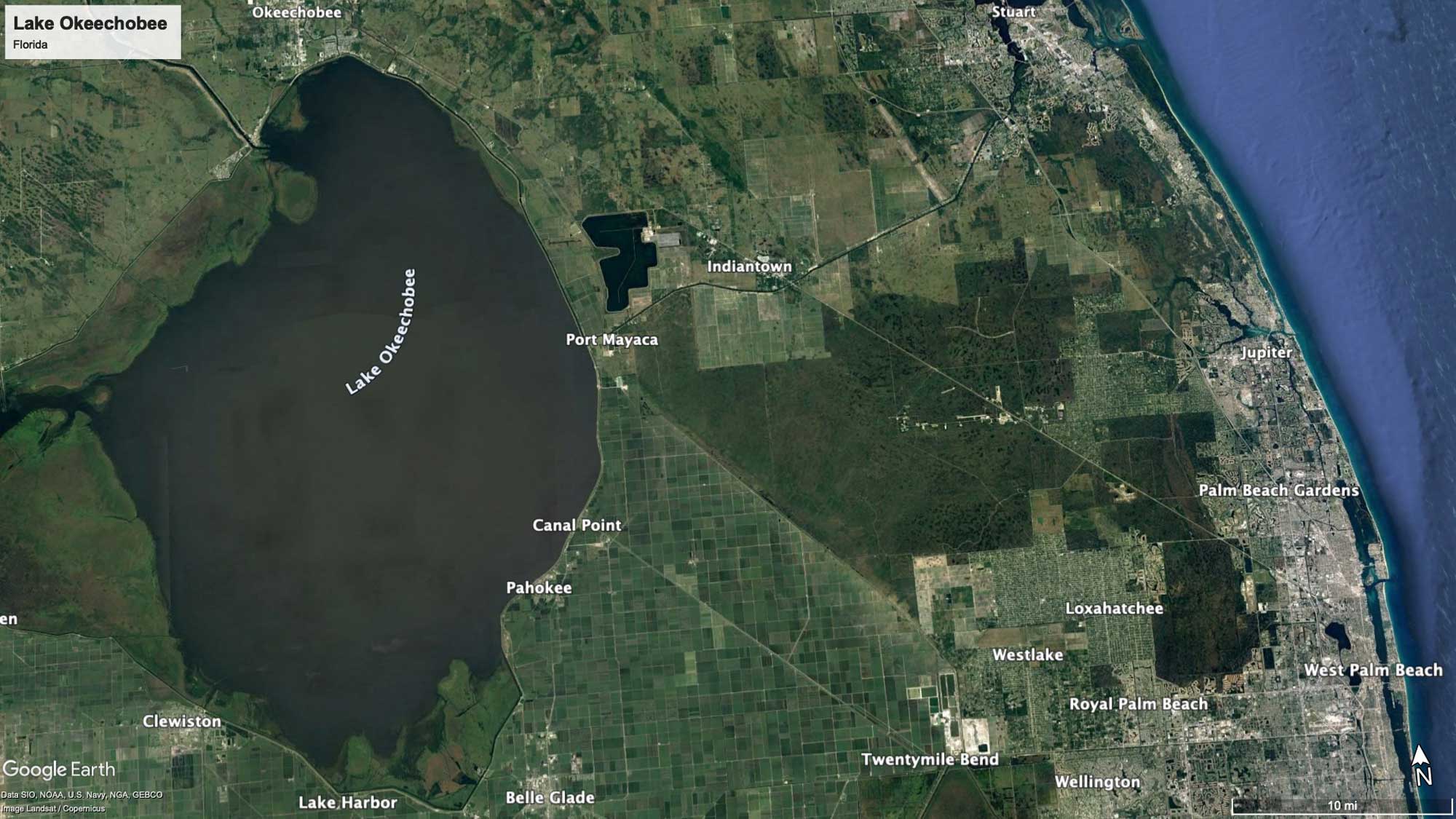

Lake Okeechobee (in the lower half of peninsular Florida) is the largest freshwater lake in Florida and the seventh largest in the US, covering 1900 square kilometers (730 square miles).

Satellite image of Lake Okeechobee, Florida. Map © Google Earth; labels added. Data from SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Image Landsad / Copernicus.

The lake sits in a shallow trough underlain by compacted clay deposits; water flowing into the topographical low originally built up wetlands that were later drowned as water level increased. Lake Okeechobee is extremely shallow, with an average depth of only 3 meters (9 feet), but it can hold 3.8 trillion liters (1 trillion gallons) of water at its fullest capacity, and it is the headwaters of the Everglades. The Everglades are the "World's Largest Sawgrass Swamp"—rarely more than 2 meters (6.5 feet) in relief, but covering 13,000 square kilometers (5000 square miles) of land. The Everglades swamp is really a river flowing south from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay. Slight topographic highs, called "hammocks," punctuate the swamp.

A hammock punctuates the Florida Everglades' vast tall-grass swamp; the birds are white ibis. Photograph taken by Kimon Berlin at the Shark Valley Trail, Monroe County, Florida (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

The Florida Keys

At the southern tip of Florida lies a curved island archipelago, the Florida Keys, extending out toward the southwest. The Keys are the exposed remnants of an ancient coral reef chain, and reefs continue to grow in the warm, tropical waters to the south. At the western tip of the Keys are the Dry Tortugas islands, a cluster of smaller islets. The majority of the Florida Keys occur in the Florida Straits, which separate the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean.

Satellite image of the Florida Keys from space. Image by NASA (Visible Earth; public domain).

The Gulf Coastal Plain and Mississippi Embayment

Gulf Coastal Plain

Most topography in the eastern Gulf Coast mimics that of the Atlantic Coast; however, beginning at Mobile Bay in Alabama, some notable coastal changes occur. Mobile Bay is a submerged, drowned river valley. East of the bay, barrier islands form close to the mainland or occur as long spits attached to the mainland (e.g., Fort Morgan Peninsula, Alabama) with only small estuarine bays behind them. West of Mobile Bay, a long line of thin, offshore barrier islands (e.g., Dauphin, Petit Bois, Ship, and Horn islands) stretches latitudinally to the Mississippi River Delta, protecting an extensive waterway called the Mississippi Sound.

The southeastern shore of Dauphin Island, Alabama. Photograph by Jeffrey Reed (Wikimedia Commons; Wikimedia Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

The Mississippi Embayment

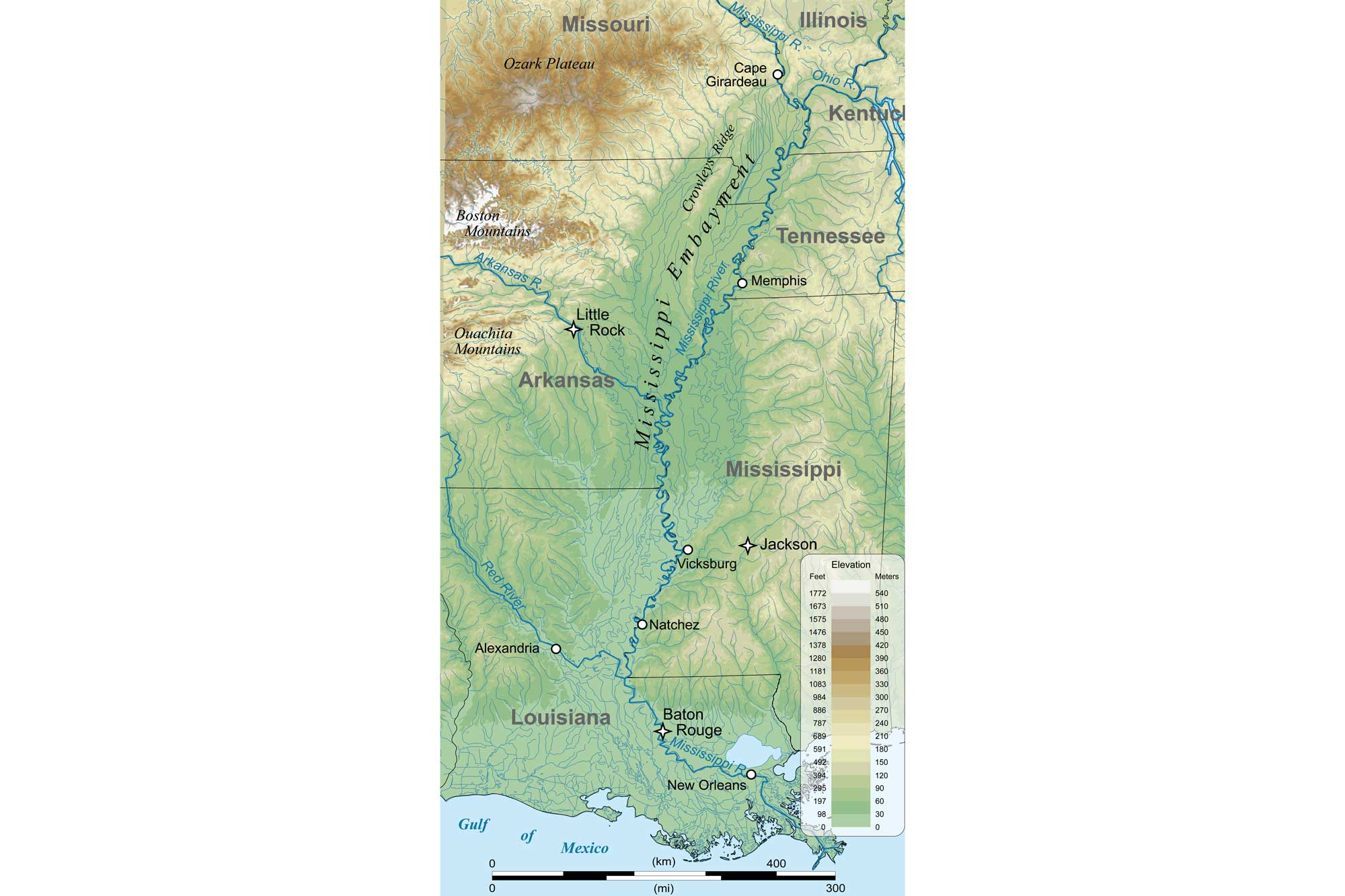

The Mississippi Embayment, stretching from Illinois to Louisiana, actually originated in the Precambrian during the breakup of Rodinia. Many smaller rifts in the crust formed adjacent to the major rift that split North America away from the supercontinent. One of these smaller rifts is located beneath the modern day Mississippi Embayment. During parts of the Paleozoic era, a proto-Mississippi Embayment existed above the rift. During the Cretaceous, the ocean flooded the embayment, and when sea level fell, the Mississippi River was born. Thousands of meters of sediment were deposited in the river valley. Mississippi’s major aquifers are found within and beneath these thick beds of sediment. Recurrent activity along faults associated with the deeply buried ancient rifts beneath the embayment caused the 1811–1812 New Madrid Earthquake, one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded in North America.

Geographic extent of the Mississippi Embayment. Image by "Kbh3rd" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license; image modified from original).

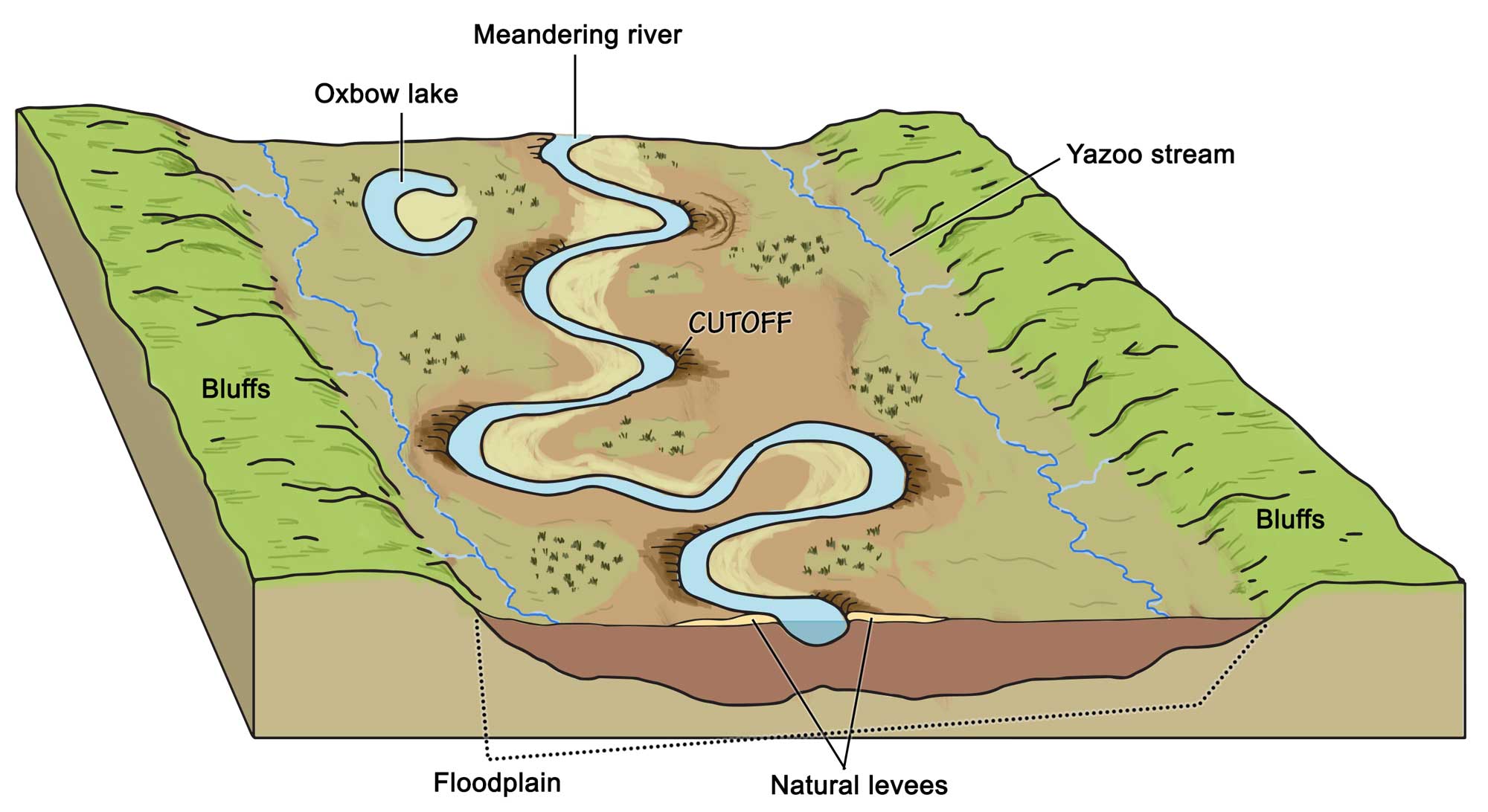

The Mississippi River Valley is bounded by a bluff line paralleling the river course, marking the extent of its meandering river path. The Mississippi is an archetypical meandering river system, and has a very low topographic profile within the valley. Maps show that the river's meandering, snake-like path that has shifted periodically, cutting off some of its loops to produce oxbows. Flanking the river itself is a pair of high, linear ridges called levees, naturally deposited during flood events, which confine the river course. These are usually the highest elevations of the otherwise wide extensive floodplain. Occasionally, "yazoo tributaries"—small tributary streams running parallel to the larger river—develop on the floodplains.

A meandering river forms when moving water erodes its banks, widening the river valley and taking on a sinuous shape. Sediments are swept up from the outside edge of river bends, where water flows more swiftly, and deposited back on the bank's inside. Over time, the river or stream forms a snaking pattern across its valley, resulting in a wide, flat floodplain and other representative features such as oxbow lakes. An oxbow lake forms when erosion cuts a meander off from the main stream, creating a U-shaped, freestanding body of water. Image by Wade Greenburg-Brand; modified for the Earth@Home project.

The extensive Mississippi River Delta, an extremely important coastal area in North America, marks the Southeast's western coastal margin. It is the United States' largest drainage basin, creating a very active depositional environment. The deposits become increasingly younger toward the gulf, due to a depositional process called progradation. During this process, the river forms a deposit at its margin, and then overflows it and deposits material on the far side in a continual outward movement. Typical of deltas, the topography here consists of low swampland and lakes. The delta's overall shape is a series of rounded lobes extending out in a "birdfoot" form as they are built up through deposition.

Satellite image of the Mississippi River Delta. Map from NASA (Earth Observatory; public domain).

In front of the delta, barrier islands are found in a more north-south orientation (e.g., the Chandeleur Islands; see map above). Gulf barrier islands are similar in topography and zonation to the Outer Banks (Atlantic Coastal Plain), but tend to be shorter and narrower. They constantly change shape due to storms entering the Gulf.

Resources

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central U.S.: Topography of the Coastal Plain (continues coverage of the Gulf Coastal Plain in Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/topography-cp/