Snapshot: Overview of the topography and landforms of the Inland Basin region of the southeastern United States, including the Valley and Ridge, Appalachian Plateau, Interior Low Plateaus, and impact craters.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction, The Valley and Ridge, The Appalachian Plateau, Interior Low Plateaus, Impact Craters.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Topography of the Southeastern US" by Michael A. Gibson and Andrielle Swaby, chapter 4 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S., 2nd ed., edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated February 25, 2022.

Image above: Cumberland Falls in southeastern Kentucky. Photograph by Jim Bauer (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Introduction

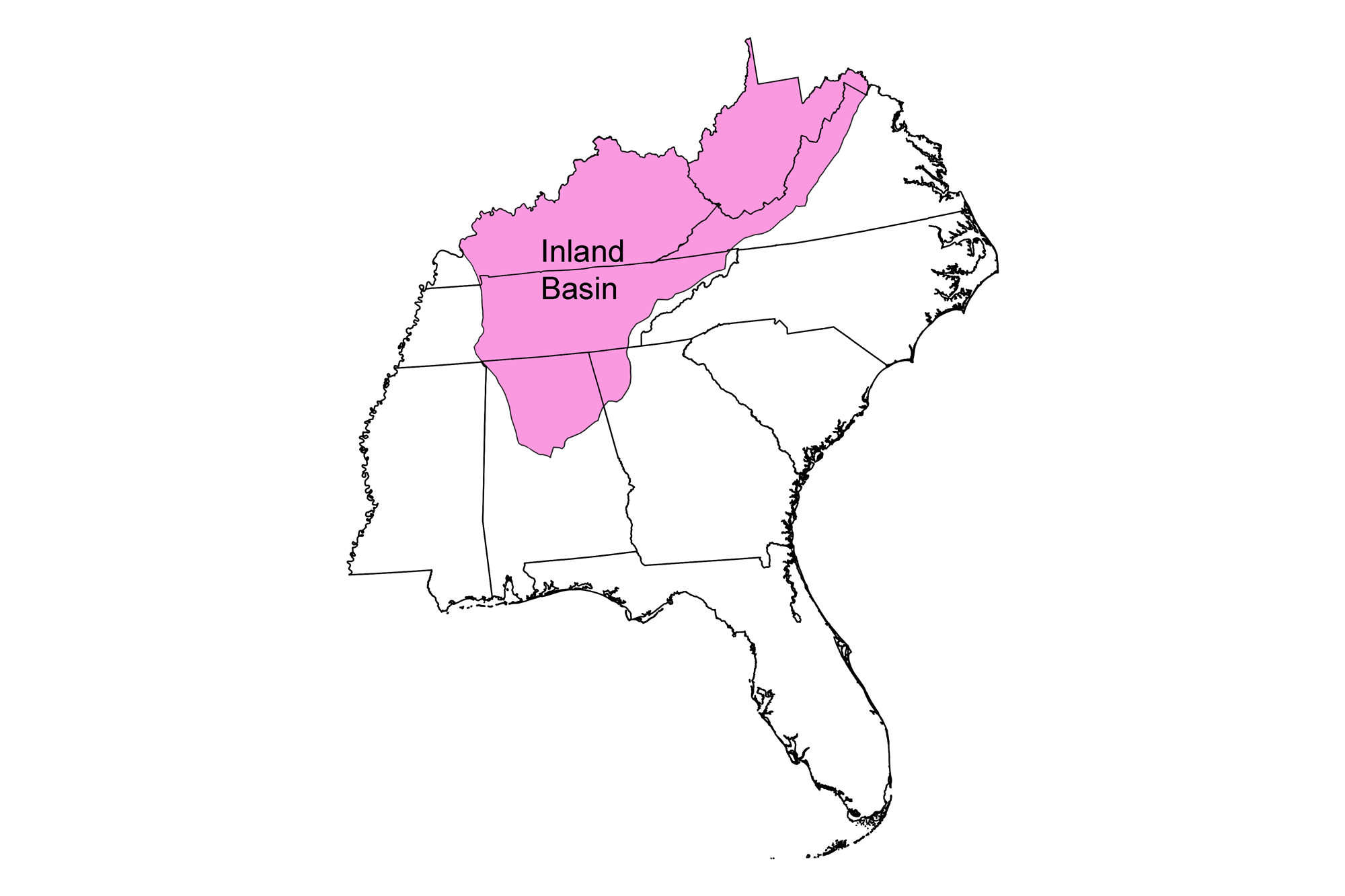

The Inland Basin, occupying the landscape west of the Blue Ridge to the Mississippi Embayment and north of the Gulf Coastal Plain, can be thought of as the Southeast's geologically stable, ancient topographic nucleus.

The Inland Basin is composed of a thick sequence of Paleozoic-aged carbonate sedimentary rock deposited during multiple ocean incursions into the continent's interior, punctuated by blankets of siliciclastic sediment from the erosion of newly uplifted mountains. This alternating stratigraphy of carbonates and clastics underlies the entire region, but it can be subdivided into several physiographic provinces based upon deformational characteristics associated with the formation of the Appalachian Mountains.

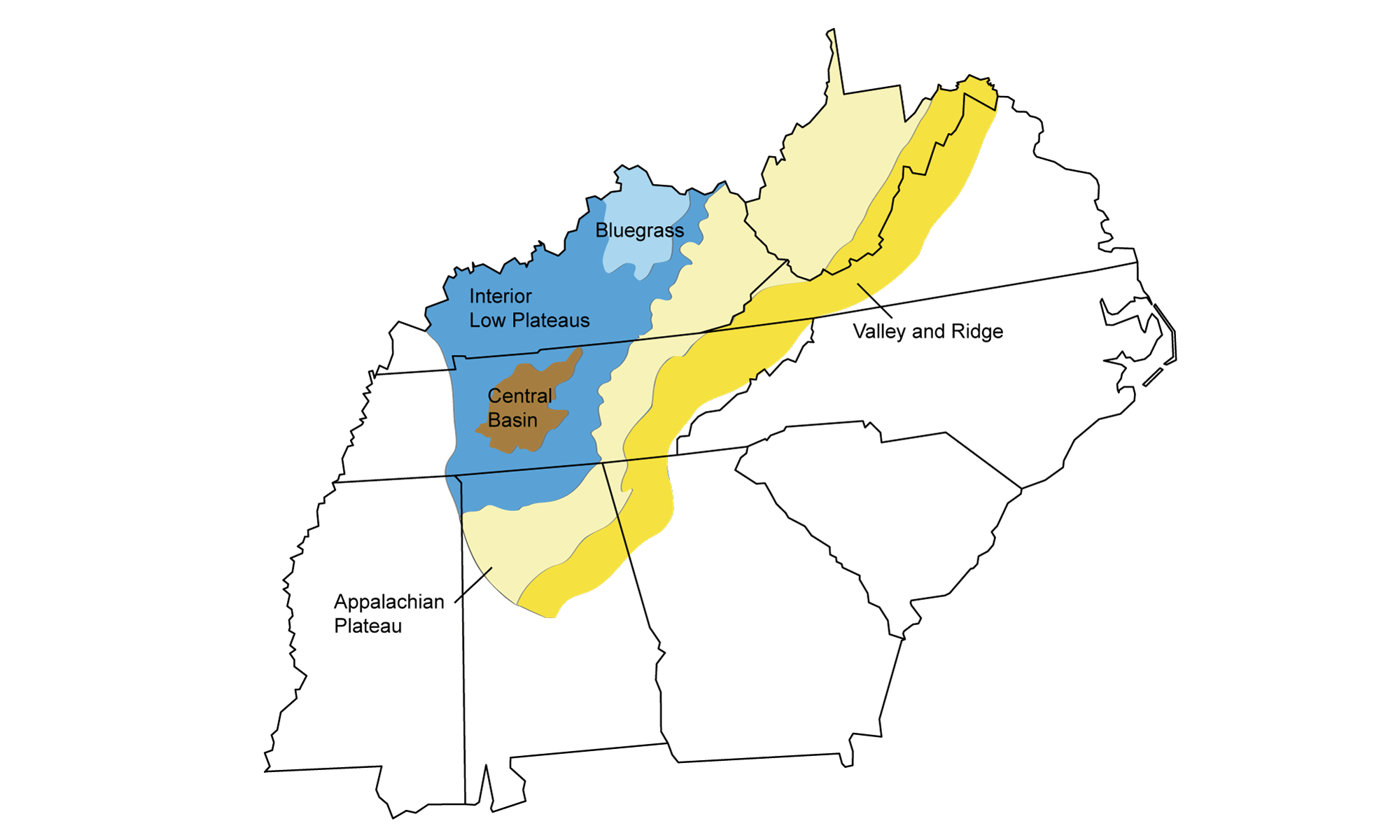

The physiographic regions of the Inland Basin. Image by Marie Regipa, modified for the Earth@Home project.

The Valley and Ridge

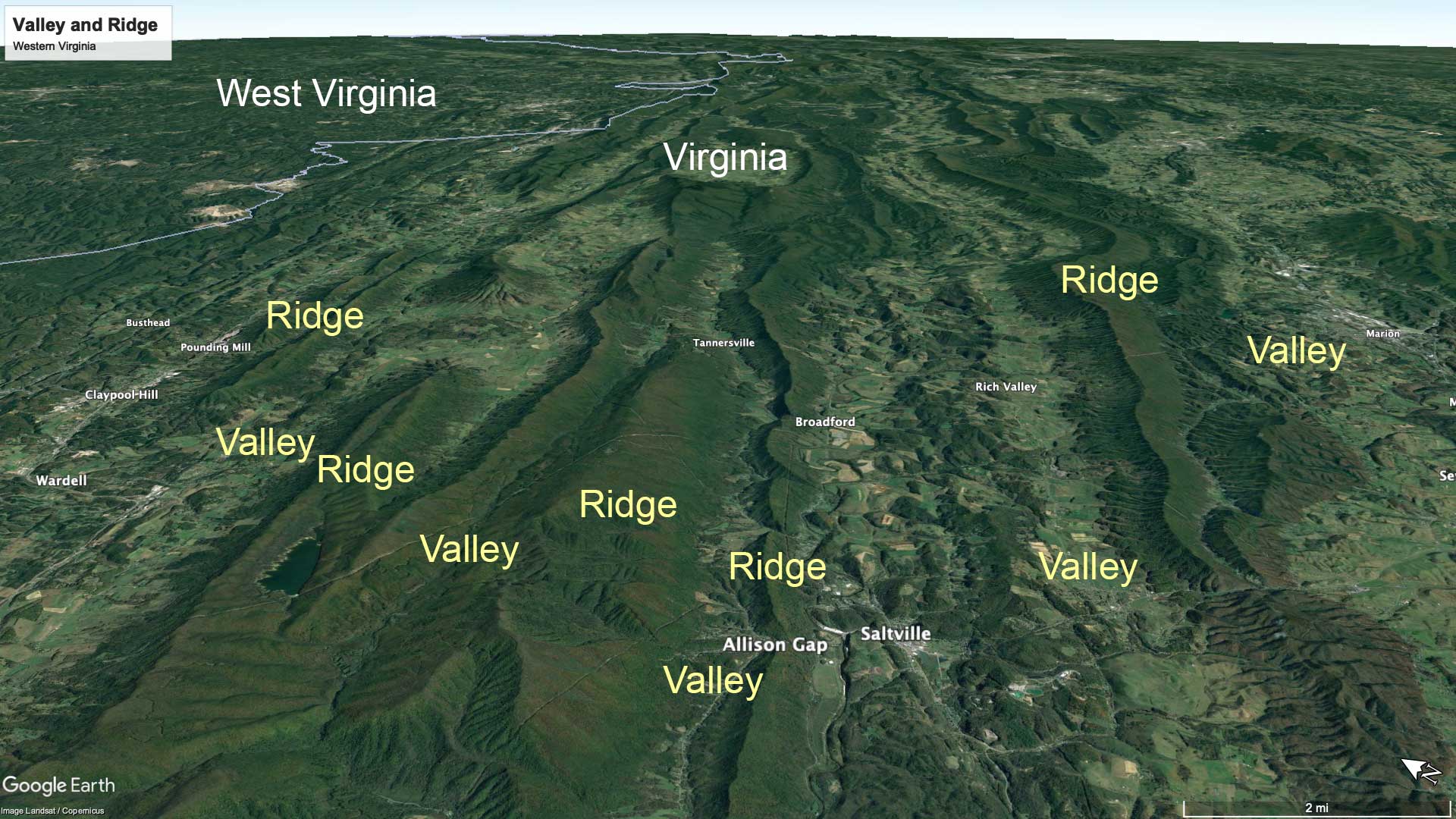

The easternmost part of the Inland Basin is a strip of linear, "wrinkled" ridges and valleys running northeast to southwest, adjacent to the Appalachians. This topography, characterized by long, even ridges with continuous valleys in between, is best developed in western Virginia and eastern Tennessee, but also extends into northeast Alabama and northwest Georgia.

Northeast-facing satellite view of the Valley and Ridge system in western Virginia. Image © Google Earth, Landsat/Copernicus; labels added for the Earth@Home project.

Individual ridge crests can run for extremely long distances—for example, Clinch Mountain in Tennessee is about 240 kilometers (150 miles) in length. The relief of ridges in this area can range from 400 to over 1100 meters (1300 to over 4000 feet) in height. Before the days of motorized transportation, the length and height of these ridges presented a major obstacle to east-west land travel, and settlers were able to cross the Valley and Ridge only near its endpoints or at erosional "gaps" created by wind and water. For example, see Allison Gap in the image above.

The elongate and folded sedimentary rocks of the Valley and Ridge were deformed by thrust faulting during the Alleghanian Orogeny, which created an accordion-like repetition of strata as sheets of rock folded and then broke to slide over adjacent areas. The ridges represent the edges of erosion-resistant strata, while valleys formed under softer and easily-eroded layers. Differential weathering and the erosion of alternating resistant sandstones and weaker shale and limestone sharpens the area's topography.

Sharp ridges of erosion-resistant, Silurian-aged Tuscarora Sandstone exposed at Seneca Rocks, West Virginia. Photograph by Ethan Gruber (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

Cemented sandstones hold up the ridges, and valleys tend to be floored by shale and karst limestone, the latter easily recognized by the numerous depressions and sinkholes that develop as surface drainage is diverted below ground. Nestled between adjacent highland areas, well-developed soils have formed thanks to the erosion of numerous sedimentary rock types, generating highly fertile farmland in the valleys.

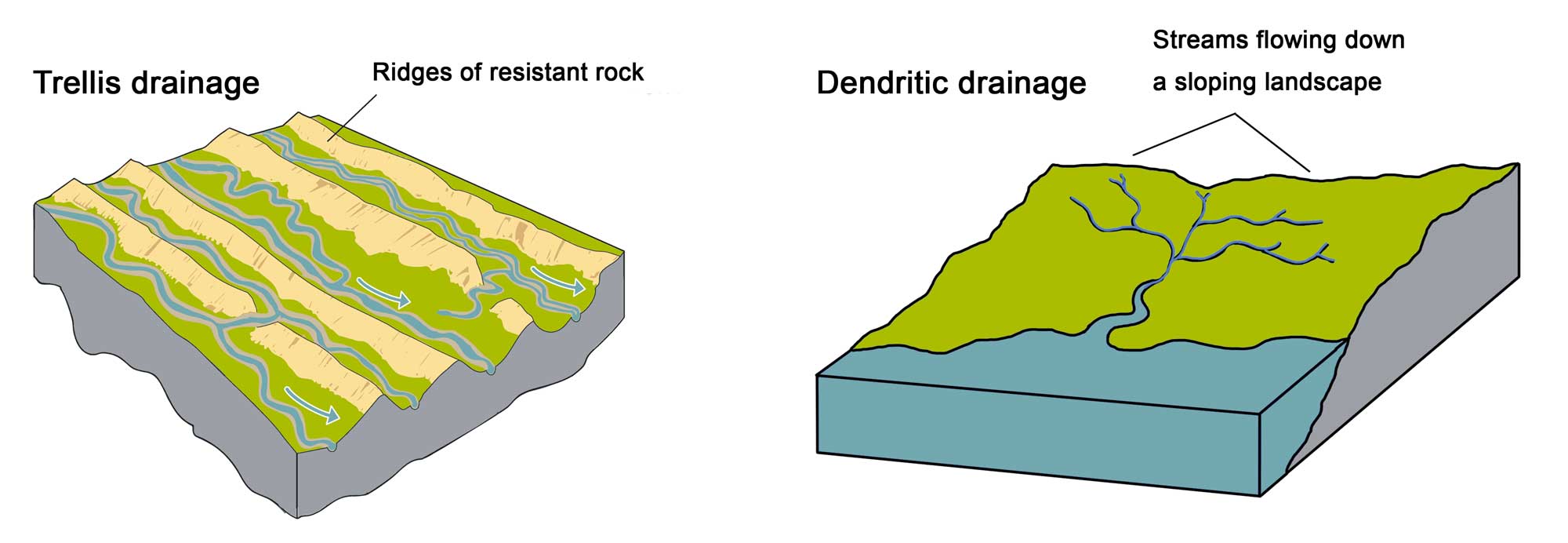

Drainage within the Valley and Ridge typically follows the orientation of valleys, with most rivers meandering back and forth across valley floors in a northeast to southwest direction. Short tributaries flowing down the ridge slopes feed the rivers. This distinctive drainage pattern, controlled by the Valley and Ridge topography, is referred to as trellis drainage. A few major rivers (including the Potomac and New rivers) have cut water gaps perpendicular to the ridges and are therefore thought to have been in place before the mountains were formed.

Comparison of trellis (left) and dendritic (right) drainage patterns. Image on left by Marie Regipa; image on right by Wade Greenberg-Brand; images modified for the Earth@Home project.

Many small streams have developed in a manner consistent with the trellis pattern, but there are a few exceptions to this rule, including the Tennessee River.

The Tennessee River

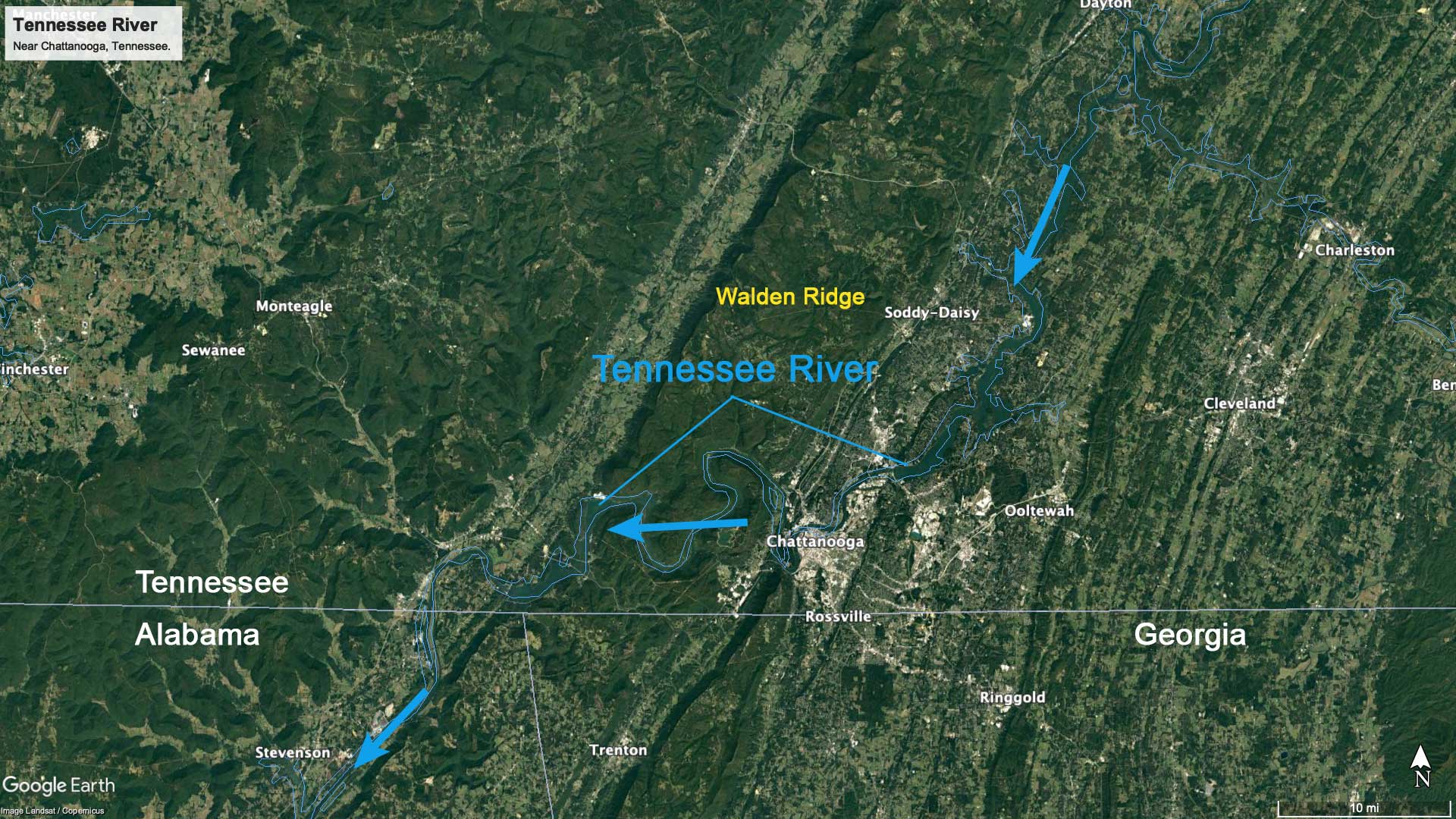

Most southeastern rivers follow a more or less direct path of least resistance from their headwaters downslope to the ocean. However, the Tennessee River seems to have a mind of its own. Its headwaters are in northeastern Tennessee on the west side of the Appalachians, which impede a direct eastern flow to the Atlantic Ocean. Rather, the Valley and Ridge trellis drainage pattern governs the Upper Tennessee, forcing it to follow valleys to the southwest. Instead of continuing its trek directly to the Gulf of Mexico, the Tennessee abruptly doglegs to the west at Chattanooga, forcing it to incise a deep canyon into Walden Ridge ("the Grand Canyon of Tennessee") before finally resuming a southwestward course.

Path of the Tennessee River near Chattanooga, Tennessee, where it cuts through Walden Ridge. Image © Google Earth, Landsat/Copernicus; labels added for the Earth@Home project.

This is only temporary, however, for the Tennessee again changes course to head west through northern Alabama, forming rapids referred to as Muscle Shoals, then onward toward the Mississippi River. Here, the river once again confounds shortest-distance convention by turning at Pickwick to flow north across Tennessee and Kentucky before emptying into the Ohio River. The Tennessee River's circuitous course has proven useful to the Tennessee Valley Authority—damming the river allowed control of floods, and the construction of hydroelectric plants helped transform the south from poverty to riches after the Great Depression.

The Tennessee River watershed, highlighted in yellow. Map by Marl Musser (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license; image resized and labels added).

Valley and Ridge in Alabama

At its southernmost extent, the Valley and Ridge enters Alabama with several major ridges and their associated valleys: Birmingham-Big Canoe Valley and Cahaba, Coosa, Weisner, and Armuchee ridges.

In the Birmingham area, Red Mountain towers above the city, exposing iron-rich sedimentary red beds that once gave the city the name "Iron and Steel Capital of the South" due to the proximity of coal for fuel and limestone for flux. In central Alabama, the entire Valley and Ridge terminates against the younger sediments of the Gulf Coastal Plain.

The Silurian sandstone strata of Red Mountain are exposed along this roadcut on the Red Mountain Expressway, near Birmingham, Alabama. Photograph by Greg Willis (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license).

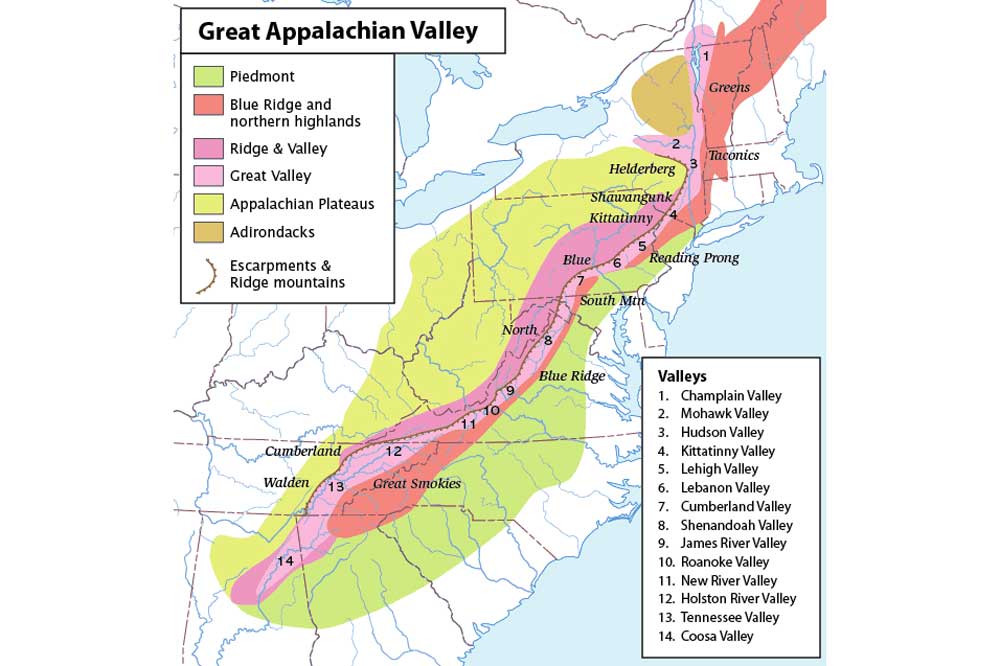

The Great Appalachian Valley

The eastern margin of the Valley and Ridge is a structural trough—a series of valley lowlands—called the Great Appalachian Valley, and it has been used as an important north-south route of travel since prehistoric times (today, it is occupied by Interstate 81 as well as portions of I-40 and I-75). The valley, which extends from Canada all the way south to Alabama, is bounded by the Blue Ridge Mountains along its eastern edge. Regional names for the Great Appalachian Valley in the Southeastern states include the Shenandoah and James River valleys in Virginia, the Tennessee and Holston River valleys in Tennessee, and the Coosa Valley in Alabama.

Map showing the full extent of the Great Appalachian Valley (light pink). Map by "Perhelion" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic license; image size changed).

The Appalachian Plateau

Westward of the Valley and Ridge, the highland rims rise and top out in a broad, high, flat plateau or "tableland" called the Appalachian Plateau. Although not as elevated as the Appalachian Mountains, these tablelands were slightly deformed into a broad, open fold, indicating their proximity to the "wrinkled carpet" deformation that made up the foreland bulge of the Appalachians. Southward, more extensive erosion has narrowed the plateaus, and the influence of underlying faulting and folding becomes more evident.

The plateau's caprock is dominated by clastic Paleozoic rocks (e.g., conglomerate, sandstone, shale, and coal) formed in extensive swamps and coastal plains while the Appalachians rose. These relatively horizontal and undeformed caprocks lessened the rate of erosion, allowing the area to lag behind the more extensively eroded carbonates exposed in the Interior Low Plateaus to the west and creating the high tableland topography we see today. Erosion continues to eat away at the area from both sides, causing it to narrow as time passes.

The Appalachian Structural Front

The eastern side of the Appalachian Plateau is a major southeast-facing escarpment called the Appalachian Structural Front. It was formed in part by northeast- to southwest-trending thrust faults. The relief along this structure is steep, and rockfalls and landslides are common environmental hazards. In West Virginia, the escarpment is called the Allegheny Front, and its highest point is Mt. Porte Crayon (1400 meters or 4700 feet). In Kentucky, it is the Pottsville Escarpment, a rugged sandstone belt of cliffs and valleys. In Tennessee, it is called the Cumberland Escarpment, and rises over 300 meters (980 feet), with grand vistas of the Valley and Ridge to the east.

A natural arch in the sandstone of the Pottsville Escarpment, Daniel Boone National Forest, Kentucky. Photograph by "J Klinger" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Regions within the Appalachian Plateau

In West Virginia, the Appalachian Plateau is divided into the Parkersburg, Logan, and Allegheny plateaus. The highest tableland in Virginia is High Knob, which rises 1287 meters (4223 feet) above sea level and contains a mixture of topographical features common to the Valley and Ridge as well as the Appalachian Plateau.

Panorama-view from the top of the High Knob Fire Tower Lookout, Virginia. Photograph by "Dirtman" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

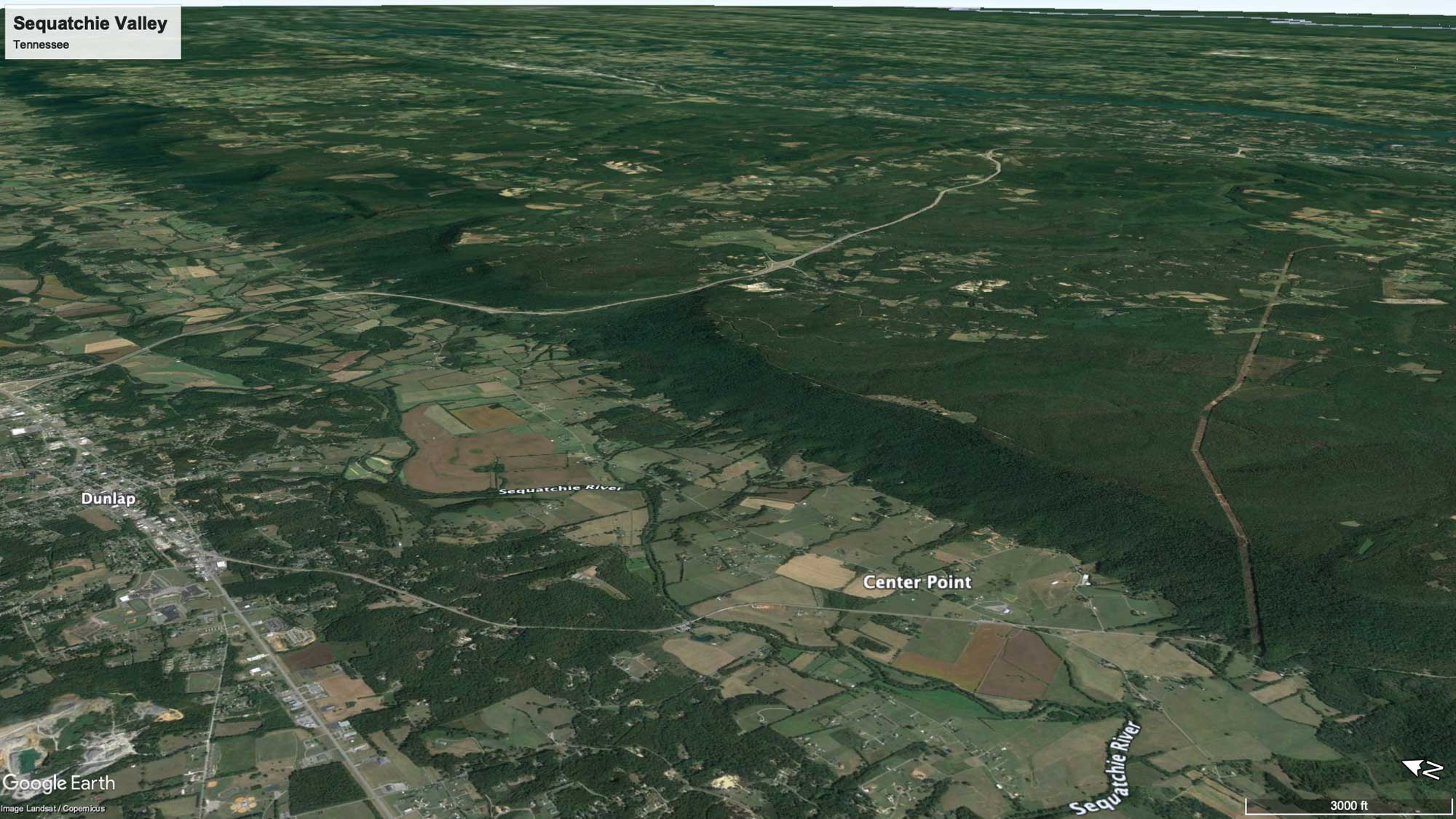

The southern portion of the tableland, stretching from Kentucky and Tennessee to Alabama, is called the Cumberland Plateau. In Kentucky, the Cumberland Plateau is dominated by forested hills and dissected by V-shaped valleys. A 201-kilometer-long (125-mile-long) thrusted ridge, Pine Mountain, extends across the area. In the northern part of the Tennessee Plateau, an unusual pattern of late Paleozoic thrust faults has created a raised and tilted uplift called the Wartburg Basin, deforming the strata into the topographically higher Cumberland Mountains—a mountain range that lies on top of the plateau. In southern Tennessee, the Cumberland Plateau is bisected by a breached anticline, the Sequatchie Anticline, that later eroded to form Sequatchie Valley—also an example of topographic inversion. This northeast-trending valley resembles a deep knife slice into the southern Cumberland Plateau extending into Alabama.

The Sequatchie Valley near Dunlap in southern Tennessee (left half of image). Image © Google Earth, Landsat/Copernicus.

The Sequatchie Valley represents the western extent of thrust faulting from the adjacent Valley and Ridge—the last of the tight wrinkles of folded strata from the continental collision that formed the Appalachians. The thrust fault shallows as it nears the surface, and was therefore more easily reached by erosion. The older Paleozoic strata exposed within the Sequatchie Valley show the classic northeast to southwest "grain" typically found in rocks farther east and at lower elevations.

Sinkholes and caverns occur in the valley where its protective caprock is breached. Grassy Cove, an enclosed valley at Sequatchie's northern tip, contains notable karst formations. Eventually, once the remaining higher layers of rock separating Grassy Cove from the rest of Sequatchie Valley are removed by erosion, it will become a northeastern extension of the main valley.

Grassy Cove, Cumberland County, Tennessee. Photograph by Brian Stansberry (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license).

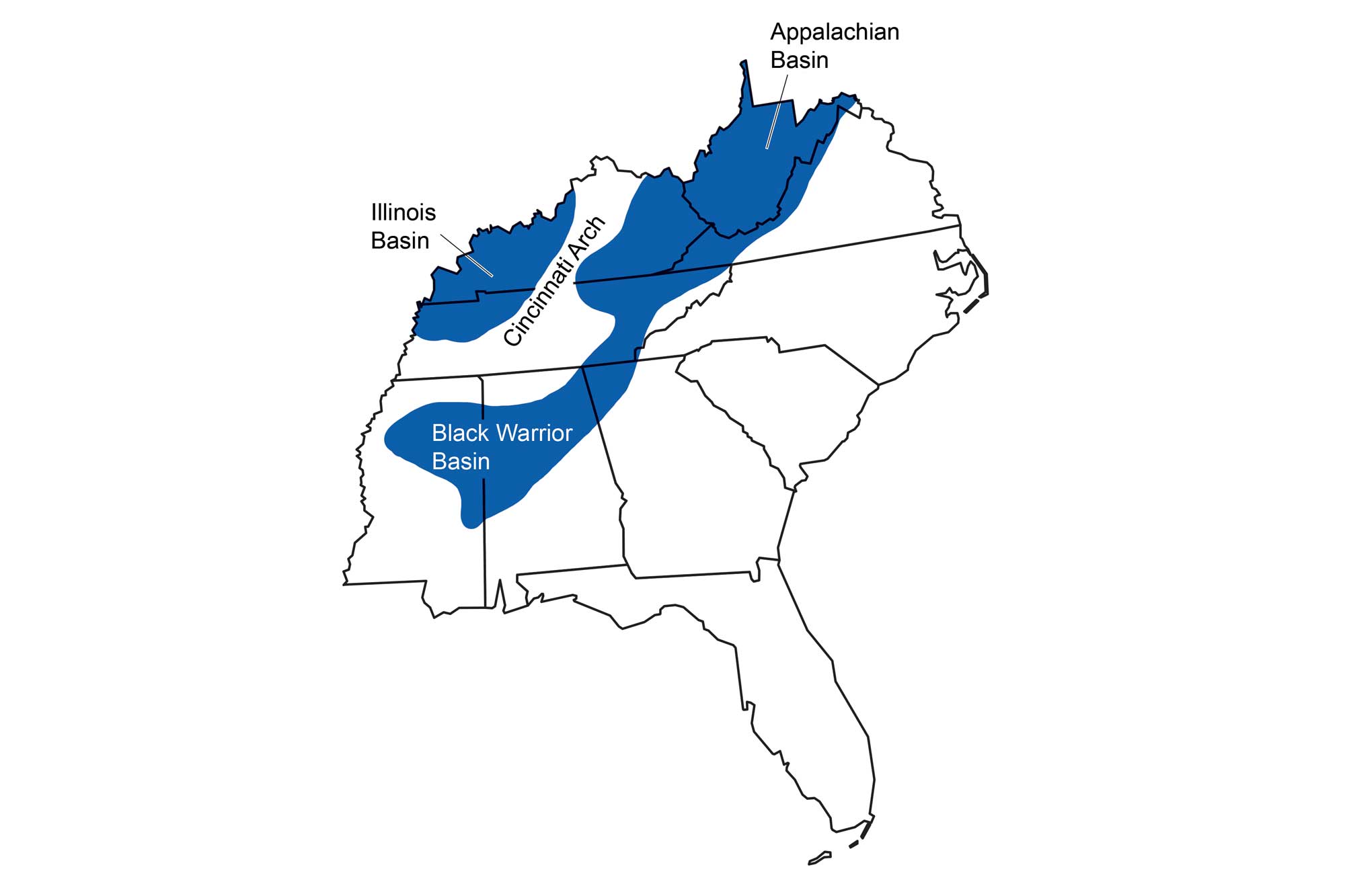

The Appalachian Plateau narrows into Alabama to become an area of flattopped plateaus, including Sand Mountain and Blount Mountain, separated by steep-sided valleys. These plateaus, which slope gently toward the southwest, flank an extensive geologic basin—the Black Warrior Basin—that lies at the southern tip of the Appalachians. The Black Warrior Basin's (see map below) topography is mostly horizontal, with tablelands formed by coal-rich clastic rocks. The eastern edges of this basin were impacted by Appalachian mountain building to become part of the adjacent Valley and Ridge topography.

The western margin of the Appalachian Plateau has an irregular geographic outline, modified by west-flowing creeks and rivers that erode the west edge of the plateau. The drainage pattern here is dominantly dendritic, flowing northwest into the basins of the Interior Low Plateaus.

Differential weathering of slightly tilted sedimentary strata has formed stair-stepped topography in the valleys, and waterfalls are a common occurrence. Fall Creek Falls in Tennessee is considered the highest waterfall east of the Mississippi River, with a plunge of 78 meters (256 feet). Cumberland Falls in Kentucky is another large waterfall, 21 meters (68 feet) high and 38 meters (125 feet) wide, that spans the Cumberland River on the border of McCreary and Whitley counties.

Cumberland Falls in southeastern Kentucky. Photograph by Jim Bauer (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Interior Low Plateaus

Broad, gently folded basins and domes with surrounding highland rims dominate the basic structure that controls the topography of the Interior Low Plateaus. Here, largely flat-lying sedimentary bedrock is close to the surface, and the area's topography is dependent on its resistance to erosion. Rolling limestone plains are punctuated with occasional rugged hills, swampy valleys, and expanses of karst. Streams and rivers cut deeply into the softer bedrock.

An extensive dome-like area, the slightly curved Cincinnati Arch, dominates the central portion of the Interior Low Plateaus.

Sedimentary basins of the southeastern United States, separated by the uplifted Cincinnati Arch. Image by WadeGreenberg-Brand; modified for the Earth@Home project.

This foreland bulge of the Cincinnati Arch parallels the trend of the Appalachians and stretches through Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee much like a slightly wrinkled rug. Erosion has breached the Cincinnati Arch's crest in several areas, forming rounded topographic basins over the otherwise dome-like uplifted strata—examples of inverted topography.

The Central Basin of Tennessee and Bluegrass area of Kentucky and the are prime examples of this phenomenon. These uplifted structural domes, now eroded into topographic basins, create bowl-shaped depressions that influence surface drainage. Except where large rivers cut the landscape, like the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers in Tennessee and the Kentucky and Licking rivers in Kentucky, drainage occurs toward the centers of the topographic basins. For example, the extensive "1000-year flooding" in Central Tennessee in 2010 occurred as rainwater filled the Central Basin faster than it could find its way out down the nearby rivers.

Downtown Nashville, Tennessee during the 2010 flooding event. Photograph taken by "Kaldari" on May 3, 2020 (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

The rims of these basins are generally steep drainage divides that expose cuts of younger to older Paleozoic strata. The bottoms of the basins expose rocks of Cambrian to Ordovician age, surrounded by the middle and late Paleozoic rocks of the rims. For example, the Central Basin is surrounded by a ridge called the Highland Rim, a hilly area that extends south into Alabama, north to the border of Kentucky, east to the Cumberland Plateau, and west to the Tennessee River.

The rocks of the Highland Rim are largely Carboniferous in age, while those exposed at the bottom of the Central Basin are Ordovician. Differences in the rock layers' durability have resulted in slight differences in the basins' internal topography, such that that they can be divided into "inner basins" of nearly horizontal strata with low rolling landscapes surrounded by "outer basins" of slightly more dissected rolling hill terrain. The Kentucky Bluegrass is an excellent example—the Inner Bluegrass is an area of gently rolling hills and rich soils of weathered limestone, while the Outer Bluegrass is characterized by deep erosional valleys. Exposed rocks in the basins are predominantly carbonates that have undergone chemical dissolution to form extensive karst topography. Sinkholes and cavern systems are common features, as are streams that disappear into the ground.

Flanking the Cincinnati Arch and its inverted erosional basins are true downwarped geologic basins that have been centers of deposition for most of their existence. These basins, which escaped the deformational mountain building processes that formed the Appalachians, accumulated and were eventually filled with thick layers of sediment. Today, the topographic expression of these horizontal layers of deposited sediment masks the basins' true structural down-warped shape. The Western Kentucky Coal Field is one such basin and is an extension of the much larger Illinois Basin that stretches into the midcontinent.

Impact Craters

Most Southeastern topography is directly attributable to tectonic forces, deposition, and erosion acting over millions of years. There are a few topographic features that are "extraterrestrial" in origin. Impact craters of varying sizes occur in many areas of the Southeast.

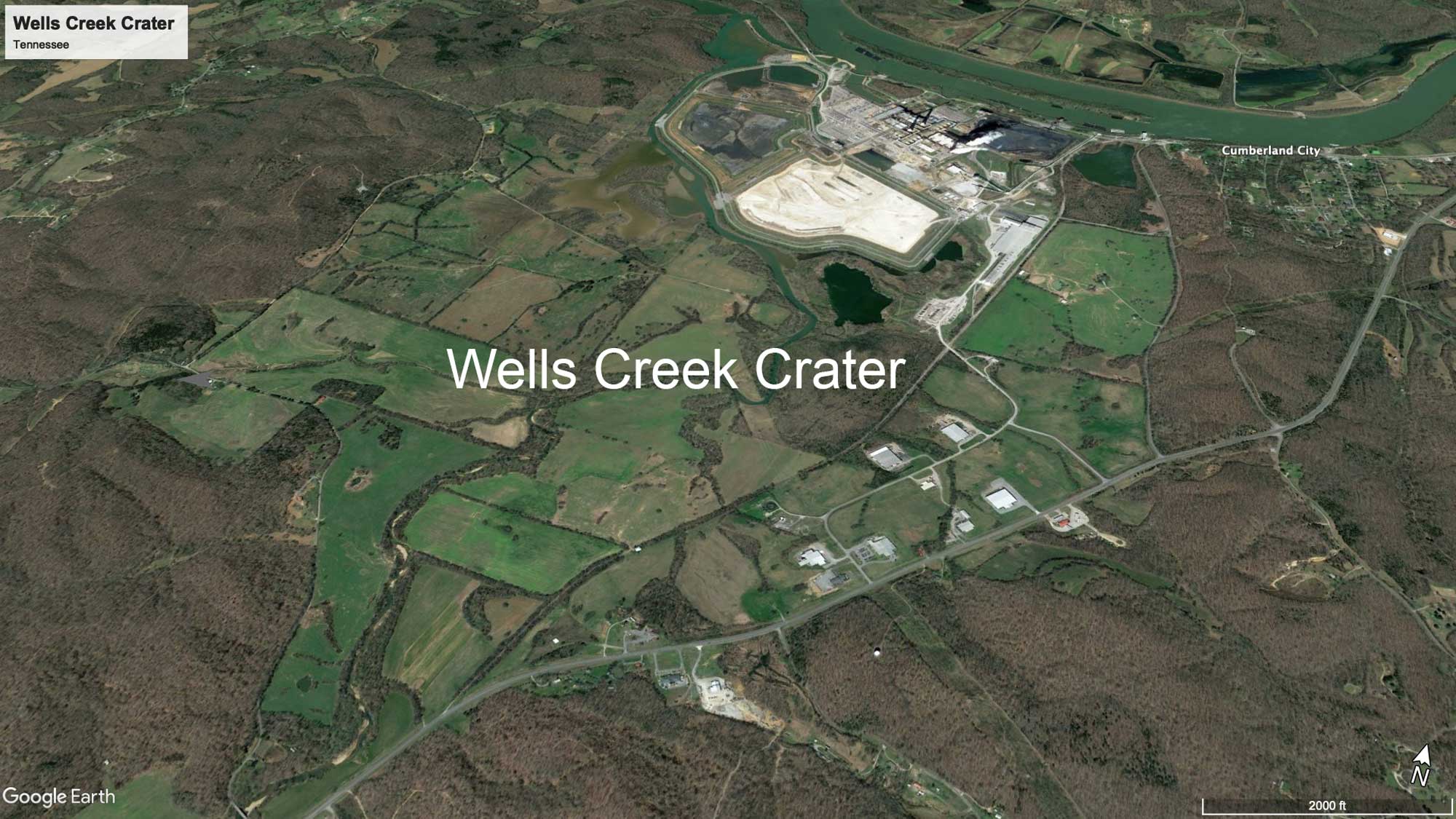

The Wells Creek Crater in northwestern Tennessee is an ancient scar produced by an impact that probably occurred during the Paleozoic. The fault-bounded circular pattern, easily visible as a basin surrounded by ridges, is over 12 kilometers (7 miles) in diameter.

Wells Creek Crater near Cumberland City, Tennessee. Image © Google Earth

The Middlesboro Crater on the Cumberland Plateau at the border of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee is also visible at the surface and contains the entire town of Middlesboro, Kentucky. Fracturing of the rocks on the edge of the Middlesboro Crater helped to form the Cumberland Gap, through which Dr. Thomas Walker and Daniel Boone opened up westward expansion beyond the Cumberland Mountains. Other craters in the Southeast include the Wetumpka impact structure in Alabama and the Flynn Creek Crater in Tennessee.