Page snapshot: Introduction to energy in the Great Plains region of the southwestern United States, including fossil fuels and renewable energy.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Oil and gas; Denver Basin; Niobrara Formation; Permian Basin; Coal; Wind energy; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Energy in the Southwestern US" by Carlyn S. Buckler and Robert M. Ross, chapter 6 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated September 7, 2022.

Image above: Abandoned coking ovens, Cokedale, Colorado. Coking is a process of heating coal to carbonize it. Carbonized coal is used in making steel. Photo by Plazak (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Overview

The Great Plains region is a broad expanse of flat land underlain by thick sequences of sedimentary rock and primarily covered in grassland and prairie. Ancient sedimentation patterns and tectonic activity have favored the placement of widespread fossil fuel resources in this region. Organic-rich sediments were deposited in inland seas that spread across much of the region, and Cenozoic swamps contributed plant matter to form thick beds of coal. The Great Plains' sedimentary basins contain vast oil, gas, and coal reserves that dominate energy production here, but the area's topography and climate also make it favorable for large wind farms.

Wastewater disposal facility (injection well) for wastewater recovered during oil and gas extraction, Platteville, Colorado. Photo: USGS (public domain).

Oil and gas

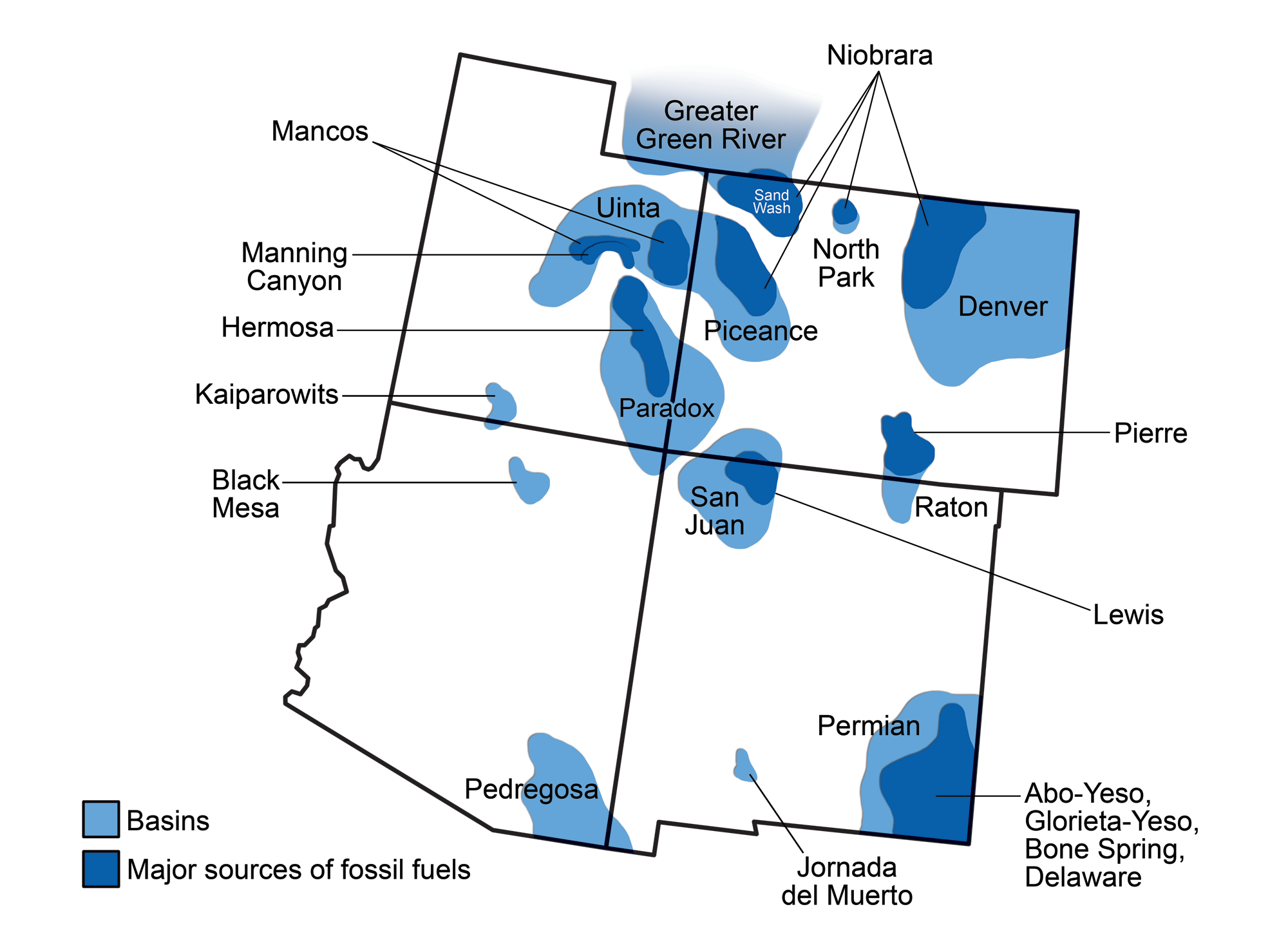

The Southwest is rich in fossil fuel resources, in part because of its history as an area of deposition. A variety of fine-grained organic-rich shales and coals, porous sandstones, and carbonate rocks—all excellent reservoirs and source rocks for fossil fuels—are found in the Great Plains' sedimentary basins. In this area, many vertically stacked reservoir rocks can be accessed through one well due to the large thicknesses of sedimentary rocks in these basins.

Sedimentary basins of the southwestern U.S. (light blue) and the oil-and-gas-bearing rock units in them (dark blue). Modified from a by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Areas of oil and gas production in the southwestern United States. The Great Plains and the Colorado Plateau are both major fuel-producing regions. Map by Andrielle Swaby, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Denver Basin

The Denver Basin is, in area, the largest of the basins in the Southwestern states, covering a large part of northeastern Colorado and the adjacent corners of Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas. The Denver Basin contains thick sequences of Pennsylvanian through Paleocene rocks, as well as Cretaceous sediments from the Western Interior Seaway.

Oil and gas have been produced from the Denver Basin since 1901, when oil was discovered in the Cretaceous Pierre Shale near Boulder. Just north of Denver, the Wattenberg Gas Field has been a major producer of natural gas since the 1970s; it has produced more than 113 billion cubic meters (4 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas. It is the ninth largest source of natural gas in the United States. Other well-known reservoir formations in the basin include the Early Cretaceous Muddy Sandstone and the Late Cretaceous Codell Sandstone.

Natural has processing plant, Wattenberg, Colorado, 2013. Photo by reid.neureiter (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Niobrara Formation

Directly overlying the Codell Sandstone is the fine-grained Late Cretaceous Niobrara Formation. The Niobrara Formation is composed of thick chalk deposits. Chalk is made up the fine-grained carbonate skeletons (called coccoliths) of phytoplankton together with shale that weathered from mountains to the west. The Niobrara Formation was deposited in the deepest parts along the eastern margin of the Western Interior Seaway. The Niobrara is so widespread that it occurs in three of the four physiographic regions in the Southwest (the Great Plains, Rockies, and Colorado Plateau) and in all the major southwestern basins except the Permian Basin.

The Niobrara Formation has been a major reservoir for oil and natural gas since the 1920s, and it has been drilled most intensively in the Denver Basin, particularly in Weld County. In the past decade, oil production rates in the Niobrara Formation have expanded enormously through the application of "unconventional" drilling ("fracking"), using horizontal drilling combined with high volume hydraulic fracturing. This method fractures rocks beneath the surface, releasing gas and oil trapped in source rocks that have very low permeability (also known as "tight" layers).

Oil tanks and pumpjacks near Pawnee National Grasslands, Colorado, 2020. Photo by Jamesmartin111 (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Drill rig and oil tanks near Pawnee National Grasslands, Colorado, 2014. Photo by WildEarth Guardians (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Lights from infrastructure for petroleum extraction near Pawnee National Grasslands, Colorado, 2014. Photo by Bryce Bradford (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Permian Basin

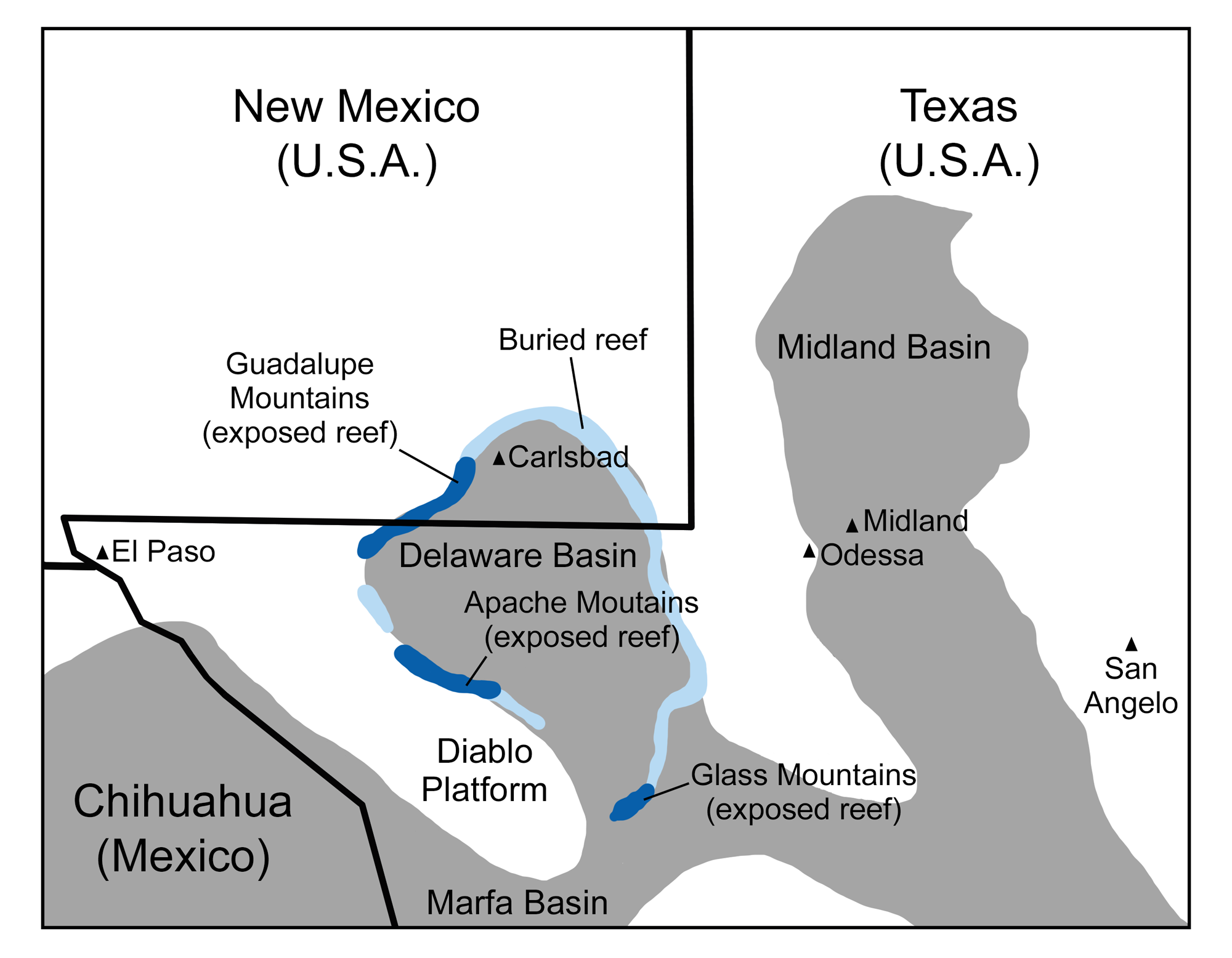

The Permian Basin, present partly in southeast New Mexico with a larger portion in western Texas, contains one of the world's thickest Permian rock sequences and accounts for nearly one-fifth of U.S. crude oil production. The "Greater" Permian Basin is composed of several sub-basins and other structural features. One of the two primary basins, the Delaware Basin, is present in southeast New Mexico (parts of Eddy and Lea Counties) and the western tip of Texas; the Midland Basin, located entirely in Texas, is the other. It contains a thick sequence of limestones and dolostones from reef and adjacent carbonate environments, together with evaporites, sandstones, and other reservoir structures that allowed hydrocarbons to accumulate.

Permian reefs of New Mexico and Texas: Map showing the paleogeographic relationship of the reefs to the topographic lows and highs of the shallow sea that covered the Texas-New Mexico-Chihuahua region in the Permian. The reef occupied the rim of the Delaware Basin. Original map by Wade Greenberg-Brand, modified for the Earth@Home project.

The Permian Basin's source rocks are largely organic-rich, shaley carbonates. The first oil wells in the Permian Basin, in both New Mexico and Texas, were completed in the 1920s, and exploration in the 1940s led to significant production by the 1950s. In the past two decades, unconventional drilling (horizontal drilling or "fracking") in a number of carbonate-rich formations has increased oil production further.

In New Mexico, new drilling has focused on Delaware Basin carbonates and a structure known as the Northwest Shelf, an area where shallow marine sediments accumulated just northwest of the Delaware Basin. Other formations of special interest include the early Permian Wolfcamp Formation (which occurs throughout the Permian Basin), the more locally occurring early Permian Glorieta-Yeso, Abo-Yeso, and Bone Spring formations, and the late Permian Delaware Group.

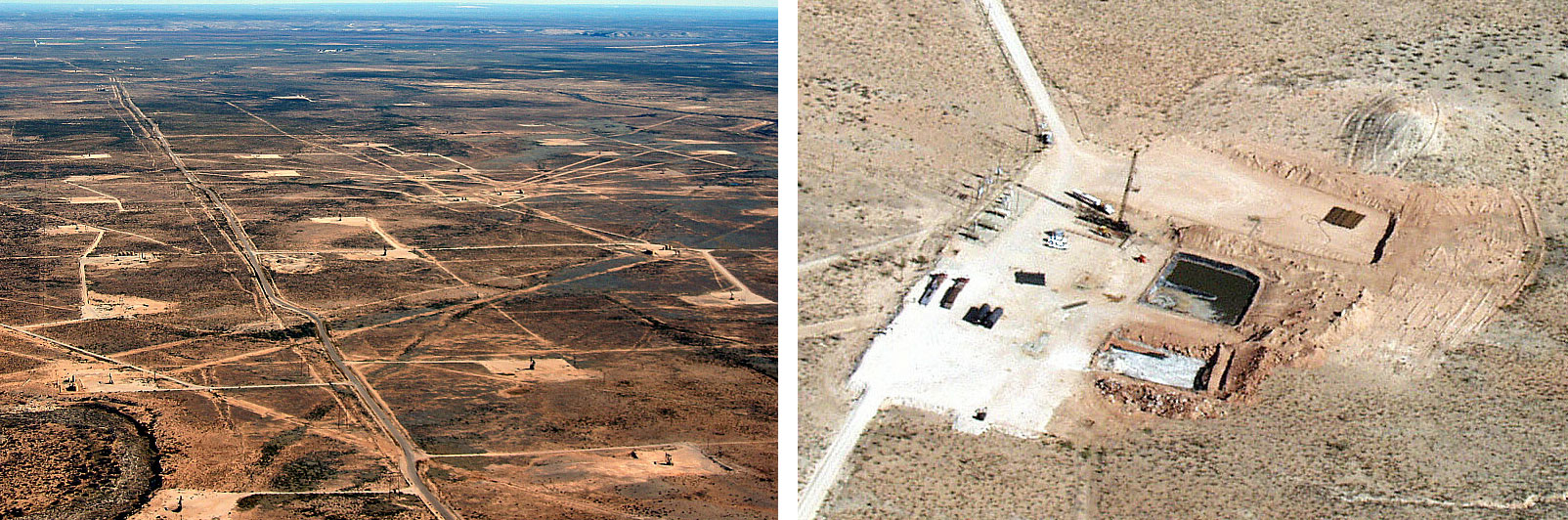

Aerial views of oil and gas development in the Permian Basin, New Mexico, 2003. Left: Oil and gas wells on the landscape. Right: Image of a single well showing well pad and associated structures. Left photo and right photo by Bruce Gordon, Skytruth/Ecoflight (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, images cropped).

A pumpjack near Carlsbad, New Mexico. Photo by JYB Devot (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Coal

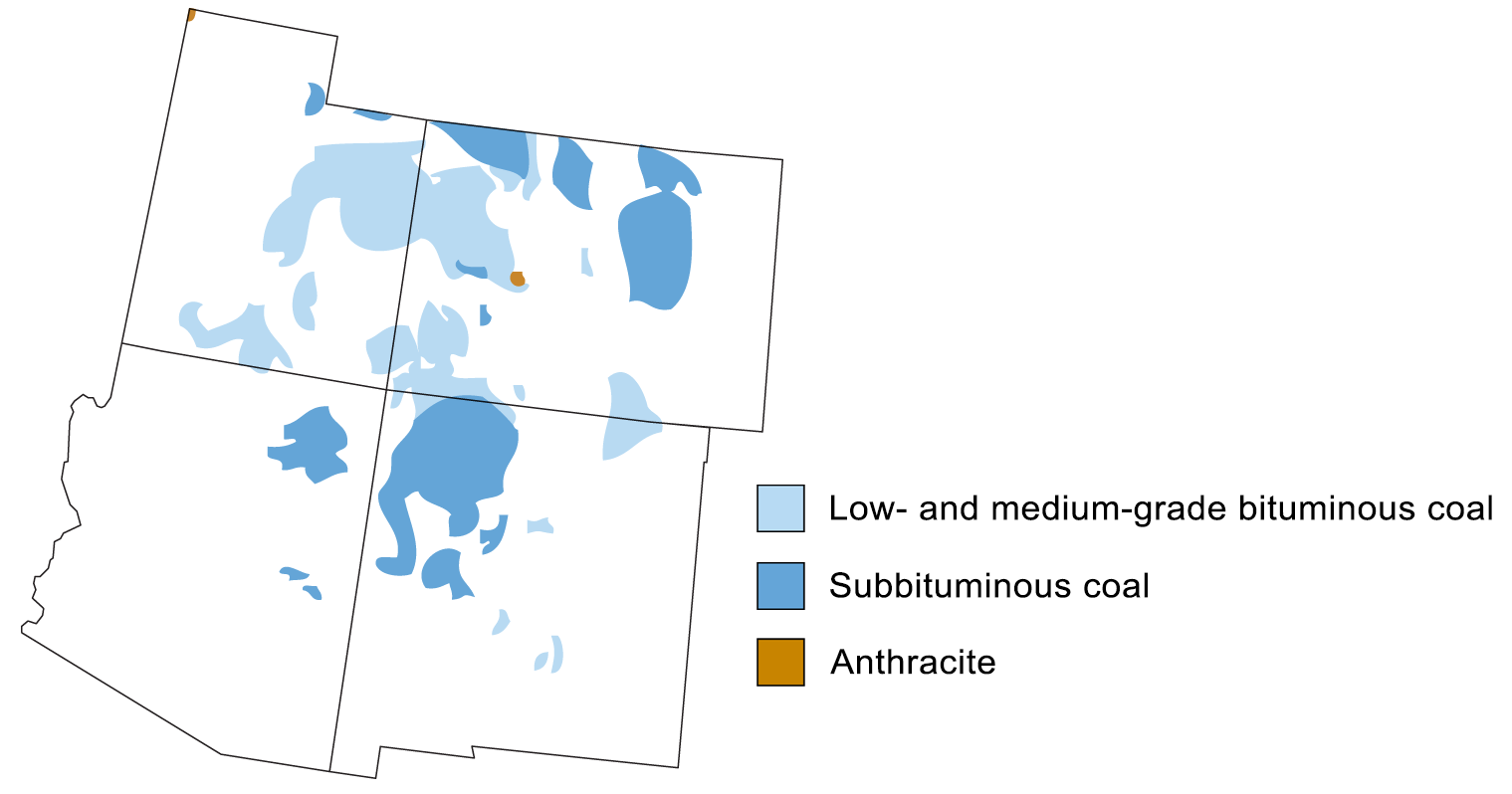

Significant amounts of coal are found in the Raton Basin, which lies along the boundary of Colorado and New Mexico. The basin contains a sequence of sediments that accumulated over a similar time interval to those of the Denver Basin. Cretaceous-aged coals in the Vermejo Formation formed along the Western Interior Seaway's deltas, and Cretaceous-Paleocene coals of the Raton Formation formed in swampy alluvial environments after the Western Interior Seaway retreated.

Raton Basin coals have been mined since the 1870s. During 1913 and 1914, the coal miners in the area went on strike, a period known as the Colorado Coalfield War. On April 20, 1914, gunfire broke out between the Colorado state militia who had been deployed to keep the peace and strikers, culminating in the Ludlow Massacre, an incident in which the militiamen looted and burned a striker encampment. Twenty-five people were killed, including 11 children in the encampment. The miners responded violently, damaging coal mines around the Raton Basin. The strike eventually failed in December 1914. A monument now stands at the site of the Ludlow Massacre, northwest of Trinidad, Colorado. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2009.

Coal mining declined substantially by the 1950s. Extraction of coalbed methane from the same formations began in the 1980s. For a time, coalbed methane from the Raton Basin became one of the largest sources of natural gas in the U.S., though it has since been eclipsed by the shale gas boom. While coal mining is not as important as it once was, it continues; the New Elk Mine began operating in 2021.

Bituminous and lignite coals have historically been extracted from the Denver Basin, but coal mining ended there in 1979.

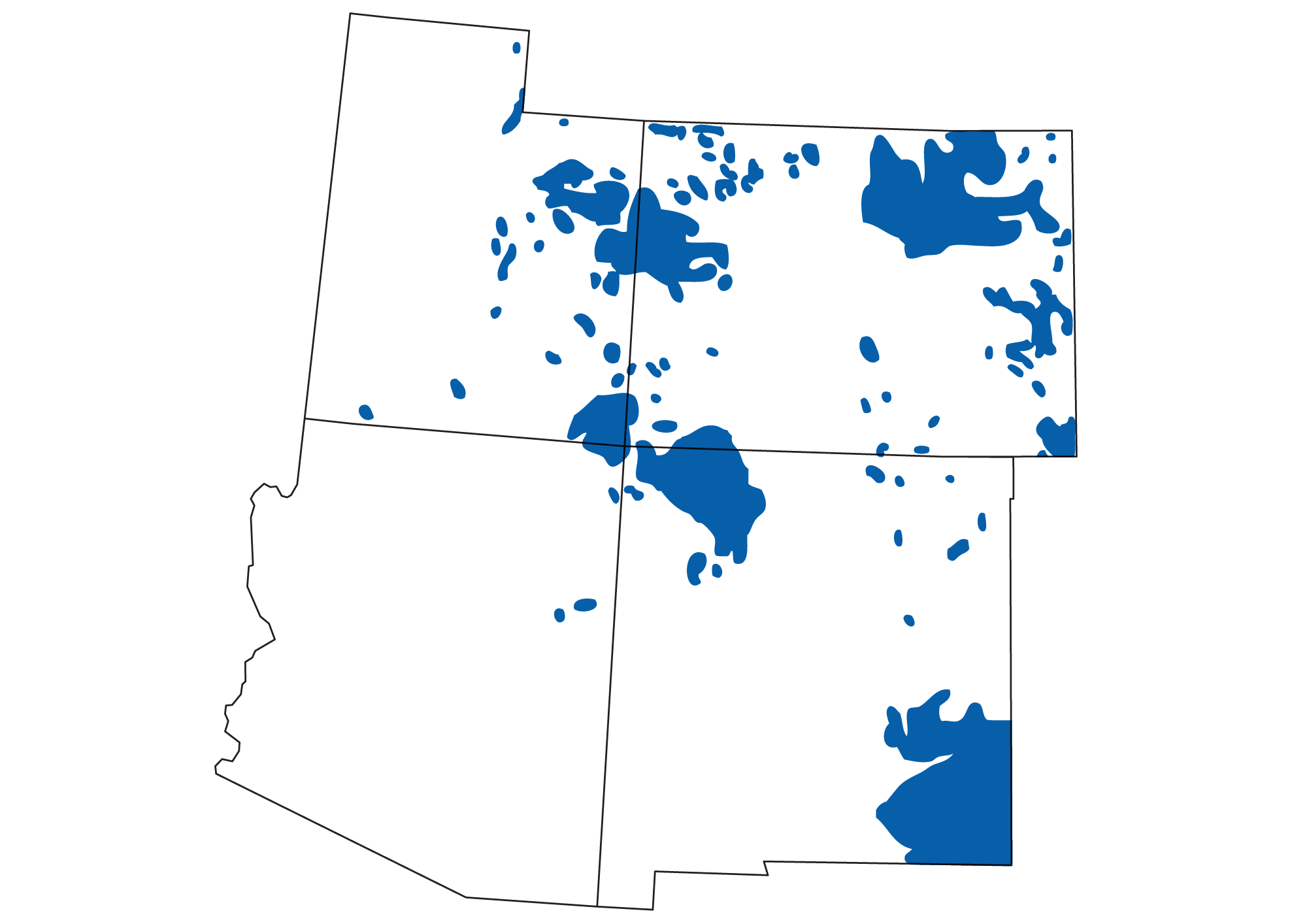

Coal-producing regions of the southwestern United States. Map modified from a map by Andrille Swaby (adapted from an image by the USGS), originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

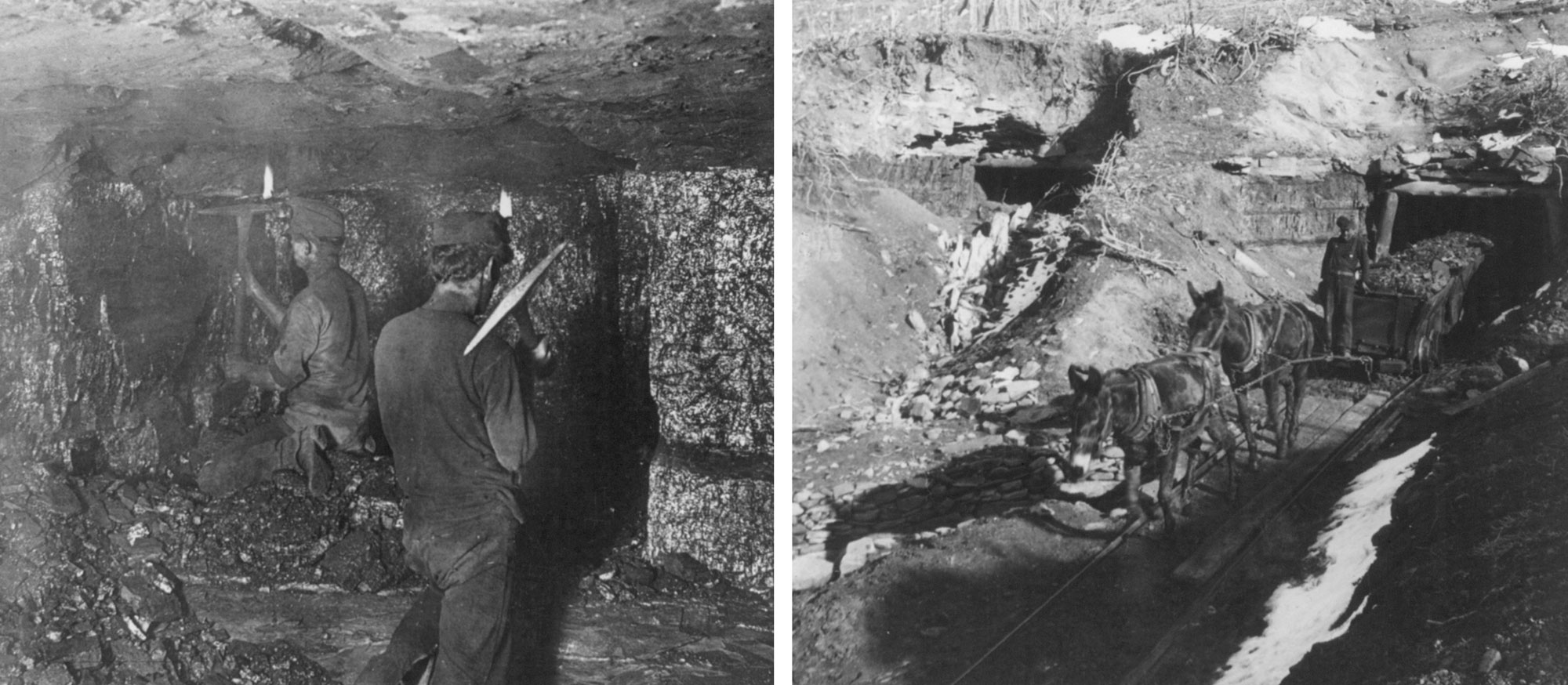

Coal mining in Starkville, Colorado, 1906. Left: Miners digging coal. Right: Coal being transported out of the mine. Left photo (Reproduction number LC-USZ62-72863) and right photo (Reproduction number LC-USZ62-72865) by H.C. White Co. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, no known restrictions on publication).

The Ludlow encampment following the Ludlow Massacre, April 29, 1914. Photo by Bain News Service (George Grantham Bain Collection, Reproduction number LC-DIG-ggbain-15859, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, no known restrictions on publication).

Monuments to mining-related tragedies in the Raton Basin. Left: Monument commemorating the victims of the Ludlow Massacre. Photo by ForgottenColorado (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized). Right: Monument to the Hasting Mine Explosion. In 1917, several years after the Colorado Coalfield War, 121 miners died in this disaster near the site of the Ludlow colony. Photo by Jeffery Beall (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Wind energy

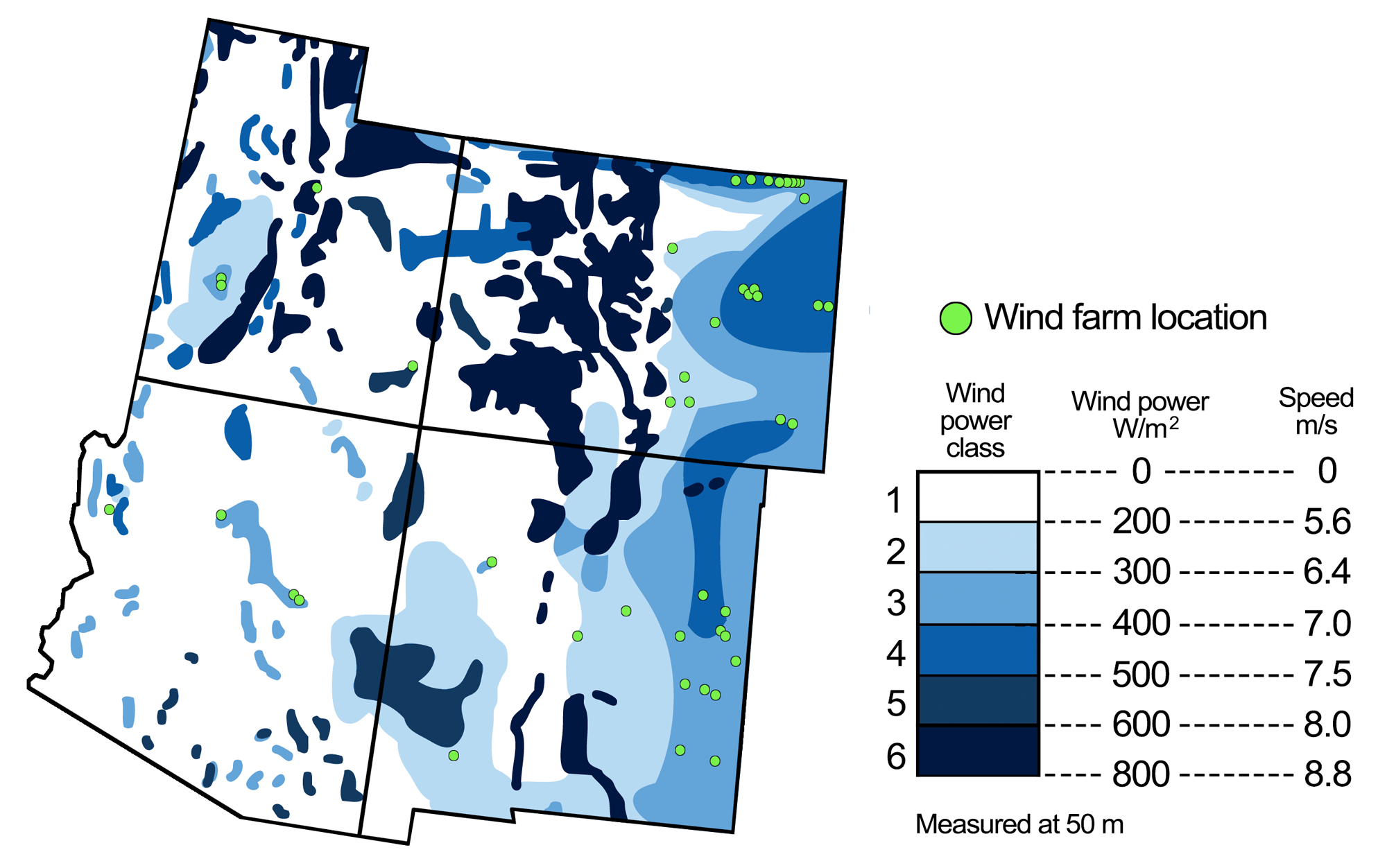

The Great Plains (in this case referring to the full area that runs from Texas to Montana and into Canada) has been called the "Saudi Arabia of Wind Energy," at least in terms of potential. Wind energy provides approximately a third of the renewable energy produced in the U.S., with hydroelectricity representing approximately half; solar, geothermal, and biomass account for the remaining sixth.

Wind energy is growing rapidly. Wind energy grew tenfold on a national scale from 2004 to 2014, and wind farms on the Great Plains played a significant role in that growth. In the Southwest, the two Great Plains states are among the top 19 states for wind energy as a percentage of state electricity generation (Colorado 14%, New Mexico 6%). This is all the more remarkable considering the high rate of local petroleum and coal extraction.

Wind energy is strong and persistent on the high plains and the uplands of eastern Colorado and New Mexico. There are especially consistent high wind speeds in the upland area of northeastern Colorado, northeast of Denver, where more than six wind farms of over 200 MW each have been built. The largest wind farm in the state, the Peetz Table Wind Energy Center, has a capacity of 430 MW. All together, the wind farms of Colorado's Great Plains make the state 10th in the nation for total wind energy. New Mexico's largest wind farm, the 250 MW capacity Roosevelt Wind Farm, is located on the Great Plains south of Clovis; the plant began operation in December 2015.

While the Great Plains also provide good opportunities for solar power capacity, this industry is still in the early stage of development in the region and only produces approximately 80 MW annually.

Wind energy potential in the southwest United States, with the locations of wind farms. Figure modified from a figure by Andrielle Swaby (adapted from an image by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory), originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Cedar Creek Wind Farm, Weld County, Colorado. Photo by UCAR (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central U.S.: Energy in the Great Plains (covers the Great Plains region in Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/energy-gp

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central U.S.: Energy in the Great Plains and Basin and Range (covers the Great Plains region in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/energy-gp-br

Here on Earth: Introduction to Energy: https://earthathome.org/hoe/energy