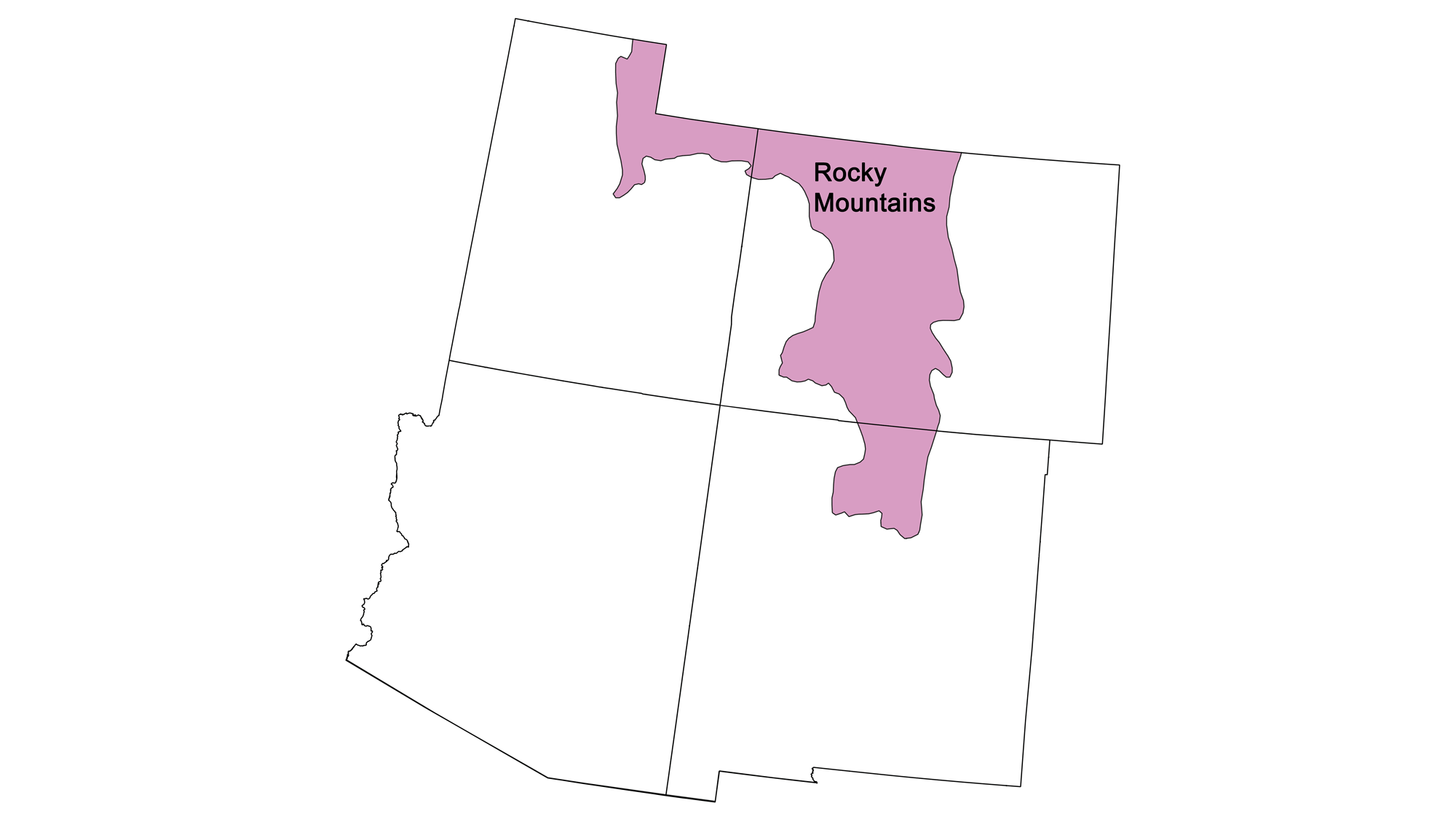

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Rocky Mountains region of the southwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Precambrian fossils; Paleozoic fossils; Mesozoic fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Paleogene fossils; Florissant Fossil Beds; Quaternary fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Southwestern US" by Warren D. Allmon and Richard A. Kissel, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 26, 2022.

Image above: Fossil yellow jacket (Palaeovespa) the late Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Paleozoic fossils

Ordovician fossils

Shallow marine waters continued to cover most of this area through the early part of the Paleozoic (Cambrian–Silurian), supporting a great diversity of life including trilobites, graptolites, brachiopods, and cephalopods. The Ordovician Harding Sandstone of central Colorado is famous for containing some of the oldest known fossil bone in the world, which belonged to fishes called pteraspidomorphs. These animals lacked jaws, but much of their bodies were covered with a bony shell made of numerous small plates. The Harding Sandstone’s depositional environment was once thought to be fresh or brackish water, but now most geologists believe it was part of a shallow marine setting.

Fossils of the jawless fossil fish Astraspis from the Ordovician Harding Sandstone of Colorado. Photo: Astraspis desiderata scute (dermal bone). Photo of USNM V 8121_1 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain). Inset (drawing): Reconstruction of Astraspis in life by Alana MicGillis (originally published in the Teacher Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US).

Carboniferous to Permian fossils

The late Paleozoic saw the seas retreat, and some Pennsylvanian layers in central Colorado, including the area around Vail and Miturn in Eagle County, accumulated in terrestrial environments such as rivers, lakes, swamps, and floodplains. Some of these sediments include significant coal deposits.

The Permian Lyons Sandstone, deposited as a series of desert sand dunes, contains abundant fossil insects and the footprints of various reptiles and amphibians.

Three views of a brachiopod (Spirifer occidentalis), Pennsylvanian, McCoy, Eagle County, Colorado. Left to right: Top, bottom, hinge. Photos of YPM IP 229698 by Jessica Utrup, 2011 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 !.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Fossil fusilinids (Staffella keytei), a type of single-celled organism with a tiny shell that lived on the seafloor, Pennsylvanian McCoy Group, Eagle County, Colorado. Scale bars = 0.2 millimeters. Photo of USNM PAL 318705 by Loren Petruny (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Mesozoic fossils

The Jurassic Morrison Formation is exposed across much of central Colorado, including at a site known as Dinosaur Ridge. This National Natural Landmark is located in Morrison, Colorado, just west of Denver. Dinosaur Ridge includes tilted exposures of the Morrison Formation (on the west side of the ridge), from which many dinosaur skeletons were collected in the late nineteenth century.

The rocks on the east side of Dinosaur Ridge are part of the Cretaceous Dakota Formation and contain hundreds of dinosaur footprints. The Dakota Sandstone, which is also exposed at Red Rock Canyon in Colorado Springs, overlies both the Purgatoire and Morrison formations and stretches into the Colorado Plateau. The Dakota Sandstone is well known for its terrestrial and marine fossils. The formation contains abundant terrestrial plants, occasional dinosaur footprints (attributed to Iguanodon and Ankylosaurus) and skeletal remains, and abundant marine invertebrates, especially mollusks and fish. The layers above the Dakota are also rich in marine fossils.

The Fort Hayes Limestone and Codell Sandstone, exposed in Red Rock Canyon and many other areas, contain abundant ammonites, bivalves, and shark teeth.

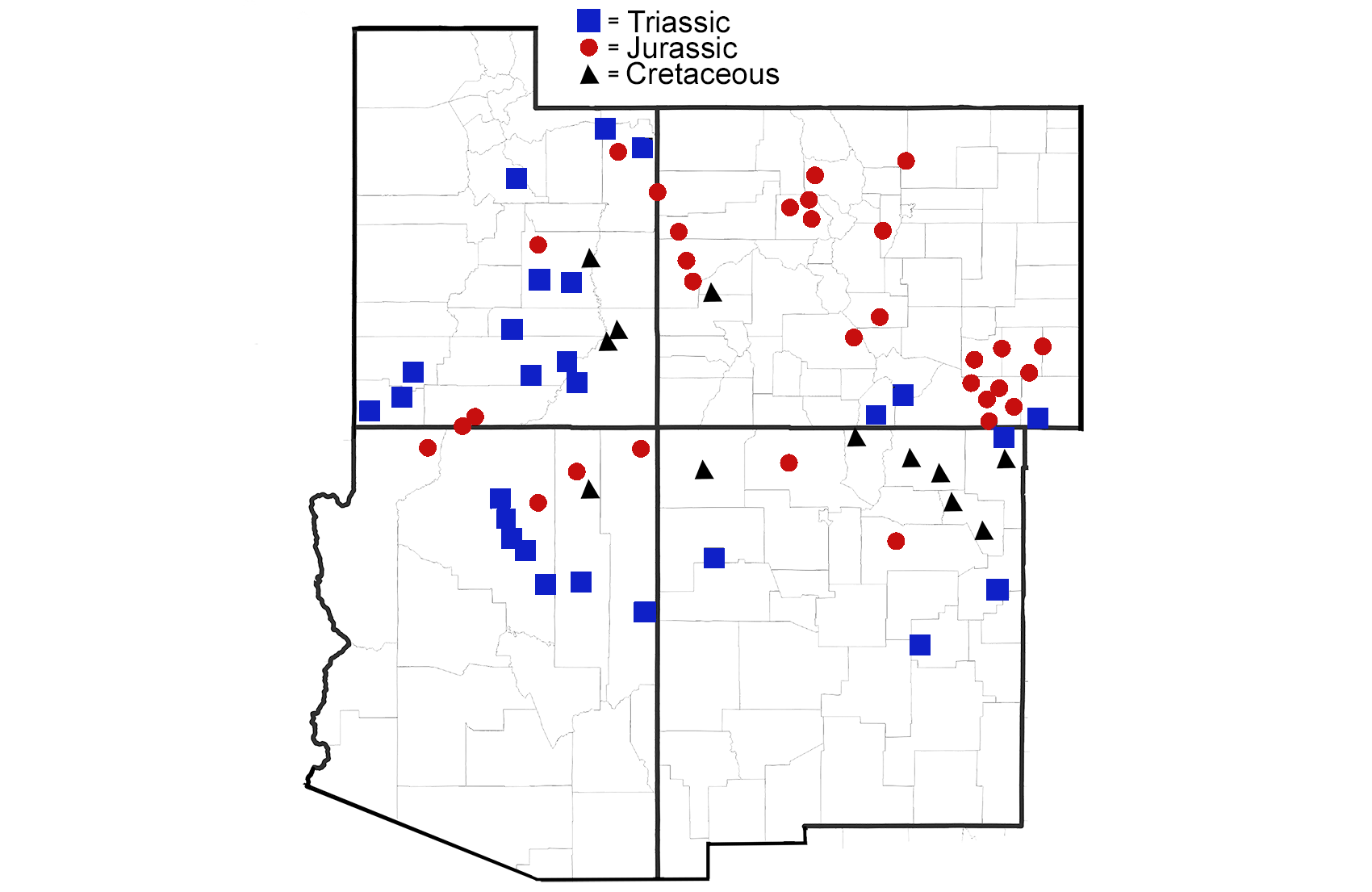

Major localities in which Mesozoic footprints (mostly dinosaurs) have been found. Map modified from a map by Alana McGillis that was compiled from multiple sources. Originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Late Jurassic sauropod footprint, Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado. Sauropods are long-necked, herbivorous (plant-eating) dinosaurs. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Early Cretaceous dinosaur tracks, Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Exposures of the Lamarie Formation near Golden, Colorado, on the border between the Rocky Mountain and Great Plains provinces, preserved dinosaur trackways and ancient palm fronds. Fossil mammals tracks have also been recorded.

The K-Pg boundary is visible on South Table Mountain south of Denver.

Triceratops track, Late Cretaceous Laramie Formation, Parfet Prehistoric Preserve, Golden, Colorado. Photo by Plazak (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Fossil palm leaf impressions, Late Cretaceous Laramie Formation, Parfet Prehistoric Preserve, Golden, Colorado. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Cenozoic fossils

Paleogene

Florissant Fossil Beds

One of the most amazing fossil occurrences in the Southwest is found at Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument in Teller County, central Colorado. There, 35-million-year-old lake sediments from the late Eocene epoch contain a huge diversity of extraordinarily preserved plant and animal fossils. Florissant's fossils were the result of massive volcanic eruptions nearby, which deposited a variety of volcanic layers including lahars, pyroclastic ash, and pumice. The layers dammed streams to form a lake that was then filled with additional volcanic deposits, as well as layers of diatoms, forming sediments known as diatomite. The extraordinary preservation of fossils in this lake may have been caused by an interaction of the volcanic ash with algal mats in the lake, inhibiting decomposition.

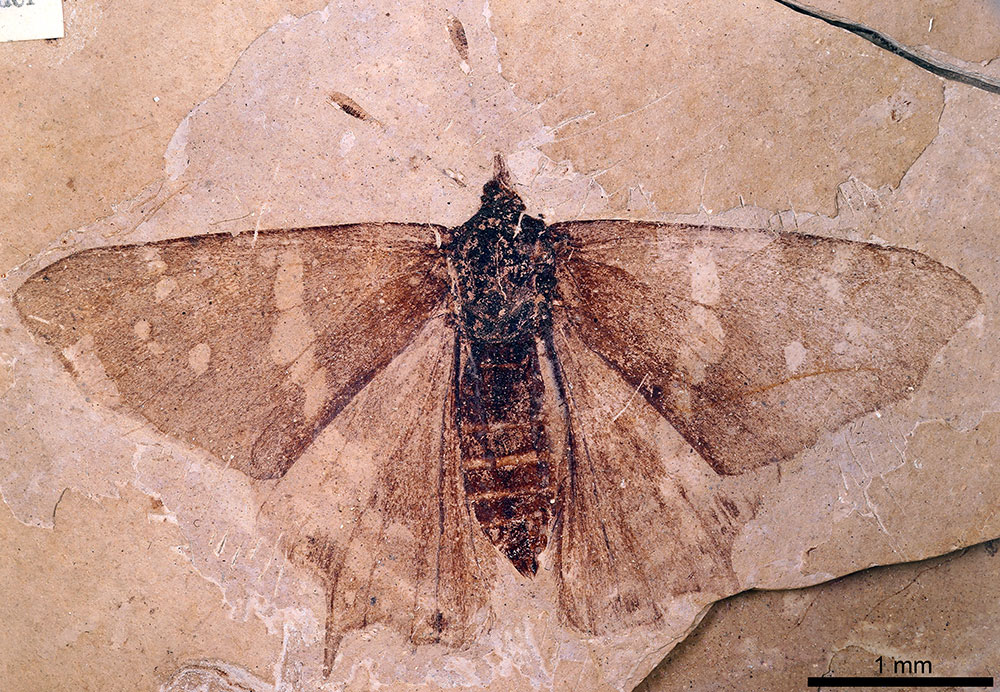

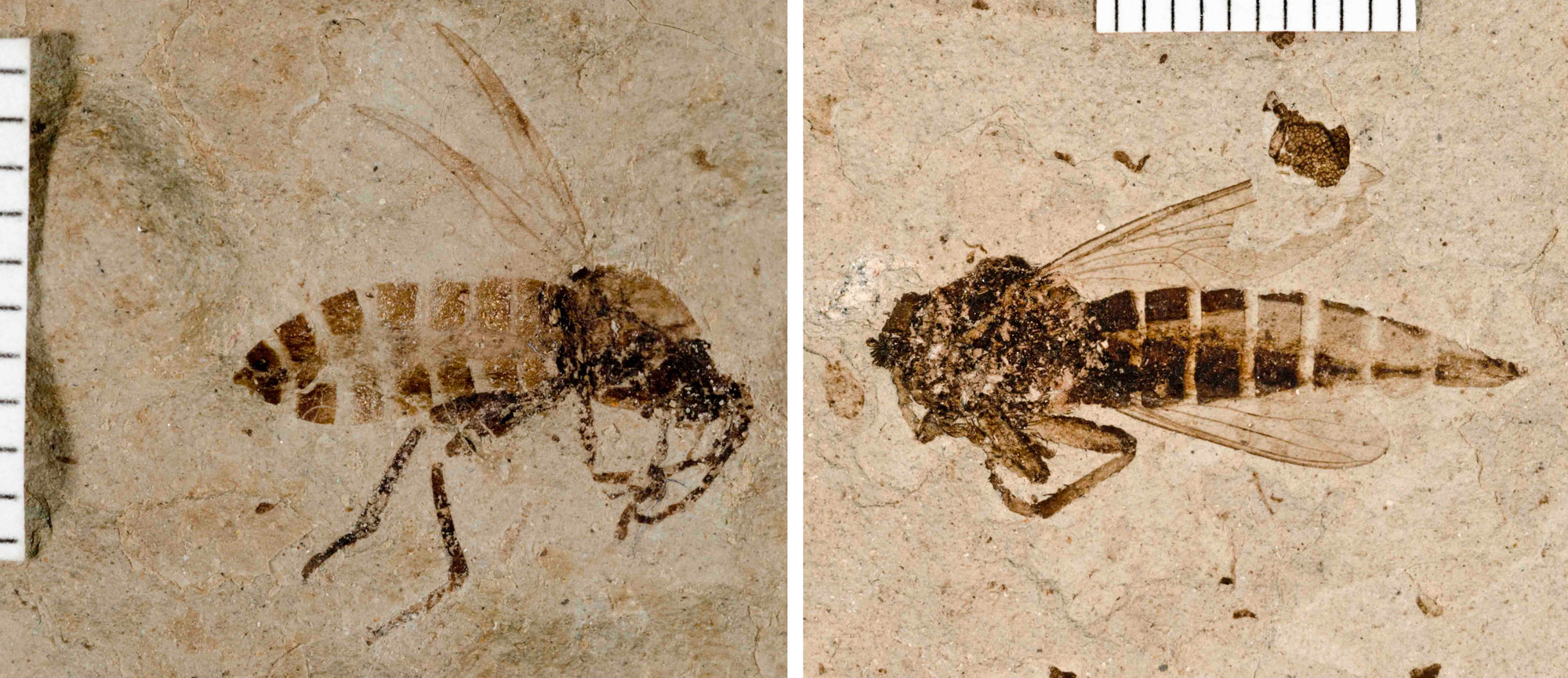

Most conspicuous among the Florissant fossils are numerous large petrified tree stumps similar to modern redwoods, which are among the largest-diameter fossilized trees in the world. Fossils of branches, leaves, fruits, seeds, cones, and flowers are also abundant. More than 1500 species of spiders and insects are preserved at Florissant, including grasshoppers, butterflies, moths, wasps, bees, ants, mosquitos, crickets, flies, and many other types of beautifully preserved arthropods. Vertebrate remains include fish, birds, and a few mammals.

Based on these fossil remains—the plants, in particular—scientists estimate that the climate of the Eocene was significantly warmer than it is today. The modern mean annual temperature at Florissant is around 4°C (39°F), while the estimated mean annual temperature during the Eocene was 13°C (55°F).

Fossil stumps of an extinct species of redwood (Sequoia affinis) at Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado. Left photo and right photo by Cassi Knight, GIP (National Park Service, public domain).

Fossil conifers, Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Left: Seed cones of a redwood (Sequoia). Center: A cedar branch (Chamaecyparis linguafolia). Right: A pine cone (Pinus florissantii). Left, center, and right images by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Branches of a tree in the Beech family (Fagopsis longifolia) showing leaves and female (left) and male (right) reproductive structures, Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Left photo (YPM PB 030121) and right photo (YPM PB 030249) by Division of Paleobotany, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

A butterfly (Prodryas persephone), Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Photo of MCZ:Ent:PALE-1 by Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), Harvard University (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, accessed via GBIF.org).

Fossil flies, Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Left: A true fly. Right: A robber fly. Left photo and right photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Dragonfly, Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Pirate perch (Trichophanes), Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

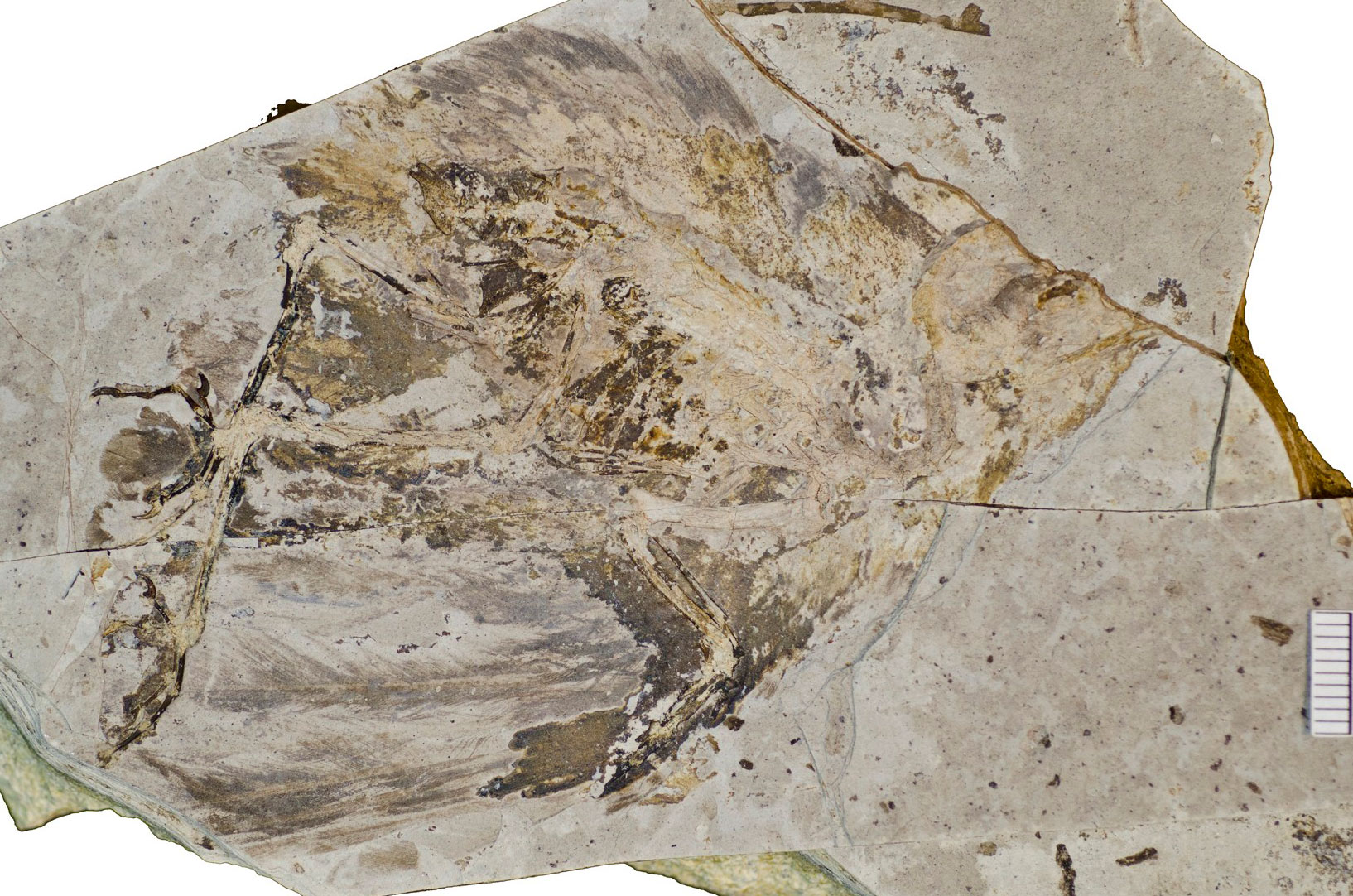

Fossil bird (a potoo?), Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. The bird is oriented sideways with its feet to the left and its head toward to right. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

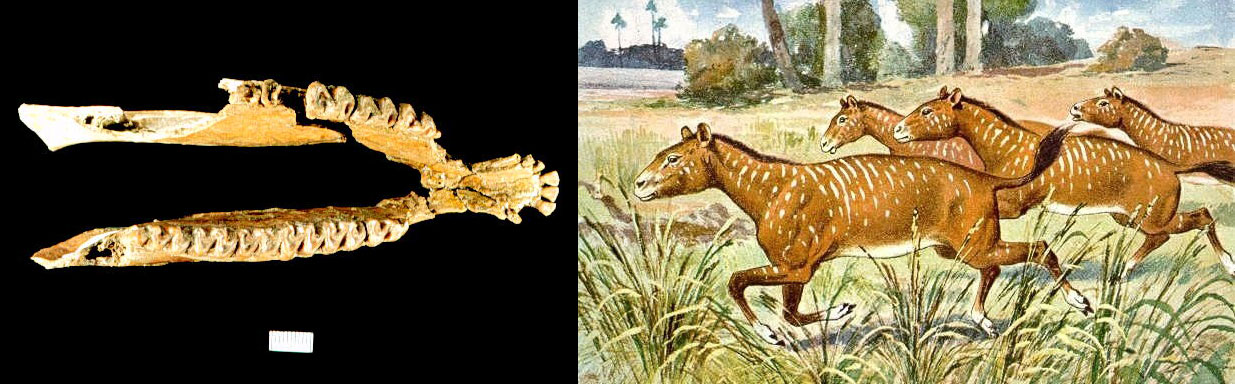

An ancient horse (Mesohippus), Eocene Florissant Fossil Beds, Teller County, Colorado. Mesohippus measured up to 70 centimeters (2 feet) at shoulder height. Left: Jaw with teeth. Right: Reconstruction of living animals. Photo and reconstruction by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Quaternary fossils

In 2010, discoveries near Snowmass Village, Colorado revealed one of the most significant sites of large Pleistocene mammals ever found in North America. There, more than 4500 bones were recovered, representing more than 40 types of ice age animals. Larger mammals included mastodons and mammoths, bison, deer, horses, camels, and ground sloths. Smaller mammals included otters, beavers, chipmunks, rabbits, muskrats, and mice. Birds, snakes, and lizards were also discovered. This site provides an amazingly well-preserved snapshot into Colorado's ice age environment.

American mastodon (Mammut americanum) tusks, Pleistocene, Snowmass Village, Colorado. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

American mastodon (Mammut americanum) molar, Pleistocene, Snowmass Village, Colorado. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central United States: Fossils of the Rocky Mountains (covers the Rocky Mountains of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-rm/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Western United States: Fossils of the Rocky Mountains (continues coverage of the Rocky Mountains in northeastern Washington): https://earthathome.org/hoe/w/fossils-rm

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/