Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Rocky Mountain region of the northwest-central United States.

Topics covered on this page: Precambrian fossils; Mesozoic fossils; Triassic fossils; Jurassic Morrison Formation; Cretaceous fossils; Cretaceous marine fossils; Cretaceous terrestrial fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Paleogene fossils; Green River Formation; Yellowstone Petrified Forest; Neogene fossils; Clarkia Fossil Beds; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Northwest Central US" by Warren D. Allmon and Dana S. Friend, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northwest Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 30, 2022.

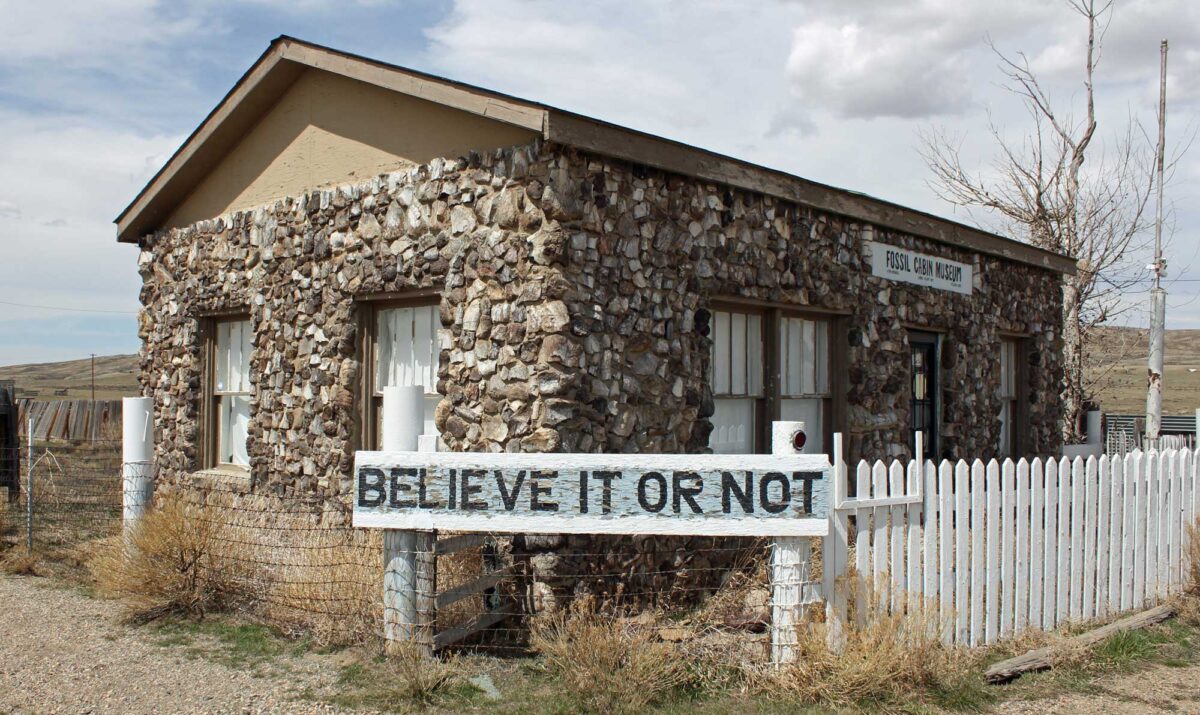

Image above: A cabin made out of dinosaur bones from the Jurassic Morrison Formation near Como Bluff, Wyoming. Photo by Jeffrey Beall (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Precambrian fossils

Paleoproterozoic rocks are exposed in the Medicine Bow Mountains of Wyoming. These sediments contain stromatolites, layered domes or mounds of sediment formed by mats of photosynthetic cyanobacteria (sometimes also called blue-green algae). The stromatolites are more than 2 billion years old.

Late Precambrian rocks are exposed in northwestern Montana (especially in Glacier National Park) and northern Idaho. They include limestones formed from carbonate sediments deposited on a warm, shallow sea floor. These rocks also contain stromatolites.

Close-up view of stromatolites in the Precambrian (Paleoproterozoic, 2.08 to 2.06 billion-year-old) Nash Fork Formation, Wyoming. Photograph by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image rotated and resized).

Precambrian stromatolites, Medicine Bow National Forest, Wyoming (note tip of boot for scale). Photograph by Kerri Lathrop, East Mountain High School (SERC, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

Close-up view of stromatolites in the Precambrian (Mesoproterozoic, about 1.44 billion-year-old) Belt Supergroup in Glacier National Park, Montana. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

Paleozoic fossils

Shallow marine waters continued to cover most of this area through the early part of the Paleozoic (Cambrian to Silurian), supporting a great diversity of life including trilobites, graptolites, brachiopods, and cephalopods. The sea retreated briefly during the middle Devonian, exposing the earlier rocks to erosion and resulting in unconformities in the geological record. Sea level rose again in the late Devonian, covering nearly all of Montana, Wyoming, and part of Idaho. These late Paleozoic seas were filled with diverse and abundant fusulinid foraminifera as well as crinoids, conodonts, mollusks, sponges, brachiopods, graptolites, and fish, including sharks.

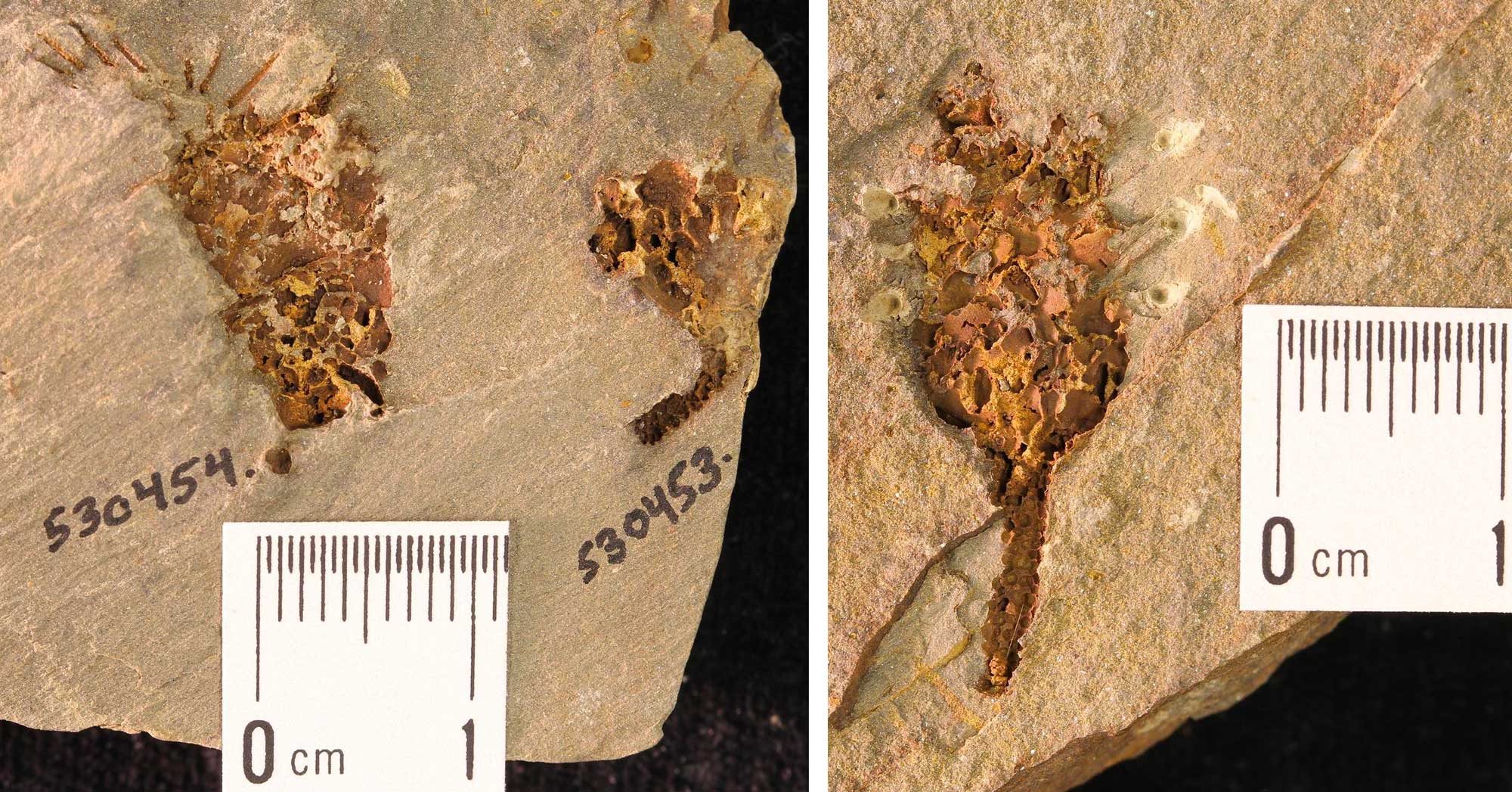

An echinoderm (Gogia palmeri) from the Cambrian Lead Bell Shale, Bear Lake County, Idaho. Photo of YPM IP 530453 and YPM IP 530455 by Jessica Utrup, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Trilobites from Cambrian rocks of Yellowstone National Park. Left: Pieces of Wilbernia walcotti, Cambrian Snowy Range Formation. Right: Pygidium of Ehmania walcotti. Left photo of USNM 35227 and right photo of USNM 90667 by Megan Norr (Yellowstone National Park on flickr, public domain).

Arms of a crinoid (Paraclidochirus schultzi) from the Devonian Three Forks Formation, Custer County, Idaho. Photo of IRN 3125888 by Crinoid Type Image Project (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

A productid brachiopod (Inflatia inflatia), Mississippian Arco Hills Formation, Custer County, Idaho. The shell is shown in three views: from above (left), from below (center), and from the hinge (right, the shell is upside down). Photo of YPM IP 207791 by Jessica Utrup, 2011 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Tooth whorl of a shark (Helicoprion), Permian Phosphoria Formation, Conda Mine, Idaho. Photo of USNM V 22577 by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Mesozoic fossils

Triassic fossils

In southeastern Idaho, Triassic deposits are largely composed of marine sedimentary rocks with sparse fossils, except for the Thaynes Formation, which contains fossils of fish, crinoids, bivalves, gastropods, ammonoids, crustaceans, and shark teeth. The Columbia Plateau has Triassic red beds and thin deposits of coal, both of which indicate some terrestrial deposition.

An ammonoid (Tirolites astakhovi), Triassic, Thaynes Formation, Idaho. Photo of USNM PAL 153081 by Bruce Martin (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Jurassic Morrison Formation

The Jurassic Morrison Formation is a layer of late Jurassic-aged rock exposed across a wide swath of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains. The silty sediments of the Morrison were deposited by eastward-flowing rivers sweeping across broad, swampy floodplains, and contain extraordinary accumulations of dinosaur bones, as well as fossils of land plants including horsetails, ferns, seed ferns, conifers, cycadeoids (an extinct group of cycad-like plants), and ginkgoes, as well as fish, frogs, lizards, crocodiles, turtles, and small mammals. The Morrison Formation dinosaurs include some of the most widely recognized in North America.

Como Bluff, a region in the Morrison Formation, is historically important as one of the sites of the "Bone Wars," a famous period in nineteenth-century paleontology when Edward Drinker Cope (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia) and Othniel Charles Marsh (Yale) engaged in a cutthroat competition to name as many dinosaurs as possible. Dinosaur bones were first discovered at Como Bluff by railroad workers in 1877. Cope and Marsh, who were already adversaries, each dispatched their own collectors to find dinosaur bones in the fossil-rich Morrison deposits in the region. Treachery, destruction of fossils, and even rock-throwing ensued among the rival collectors.

Marsh ultimately bested Cope in the Bone Wars. More of Marsh's names for major Morrison Formation dinosaurs are widely recognized today, including the predator Allosaurus, the spike-tailed Stegosaurus, and the sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs) Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, and Diplodocus. Cope named the sauropod Camarasaurus. Publicity around the Bone Wars and the feud between Cope and Marsh, which lasted until Cope's death in 1897, eventually had a negative impact on the careers and finances of both men.

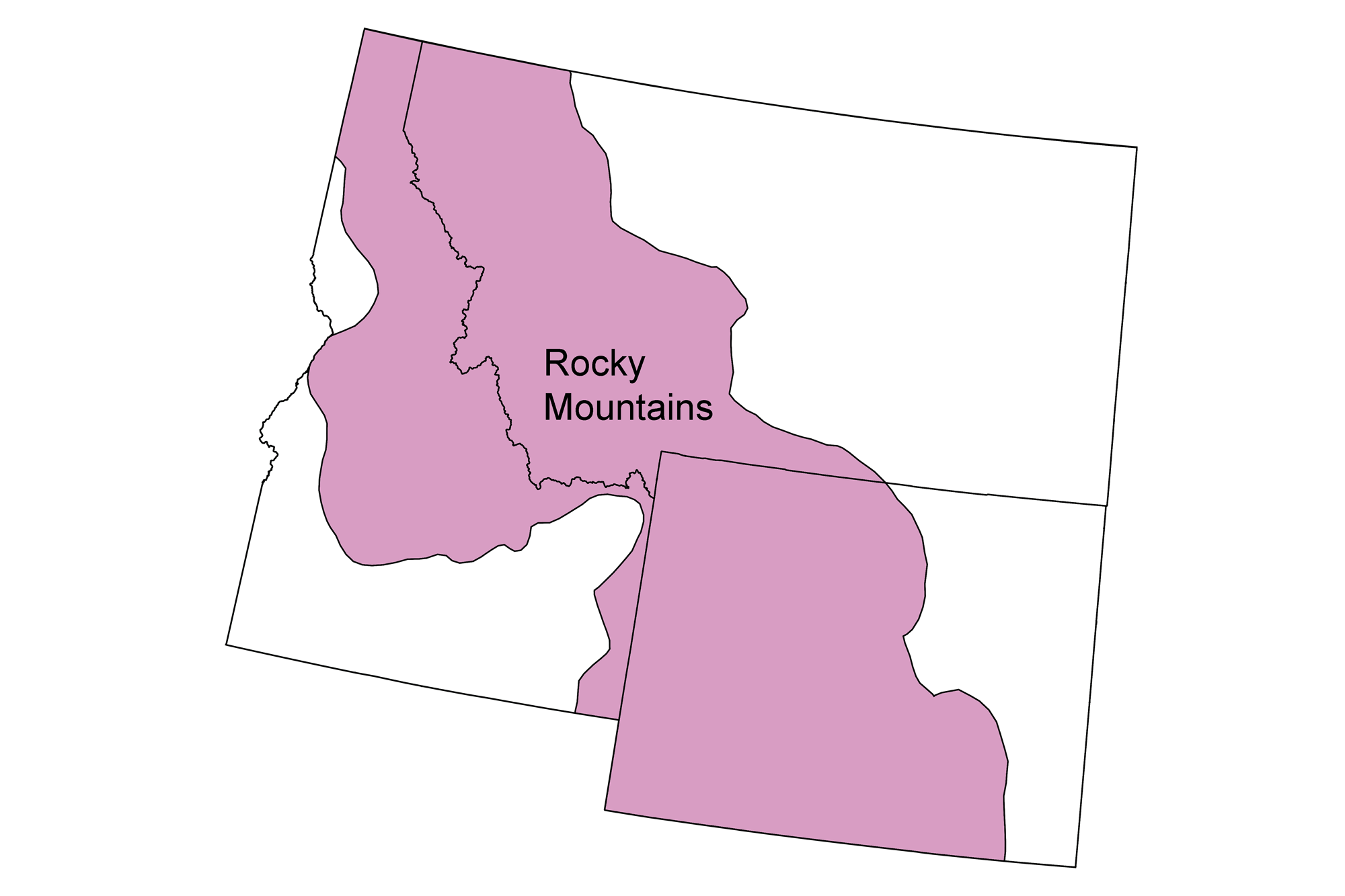

Geographic extent of the Jurassic Morrison Formation. Map modified from a map by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US.

Cycadeoidea from the Jurassic Morrison Formation, Freezeout Hills, Carbon County, Wyoming. Left: A portion of a trunk. Right: Detail of leaf bases on the outside of a trunk. Left photo and right photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

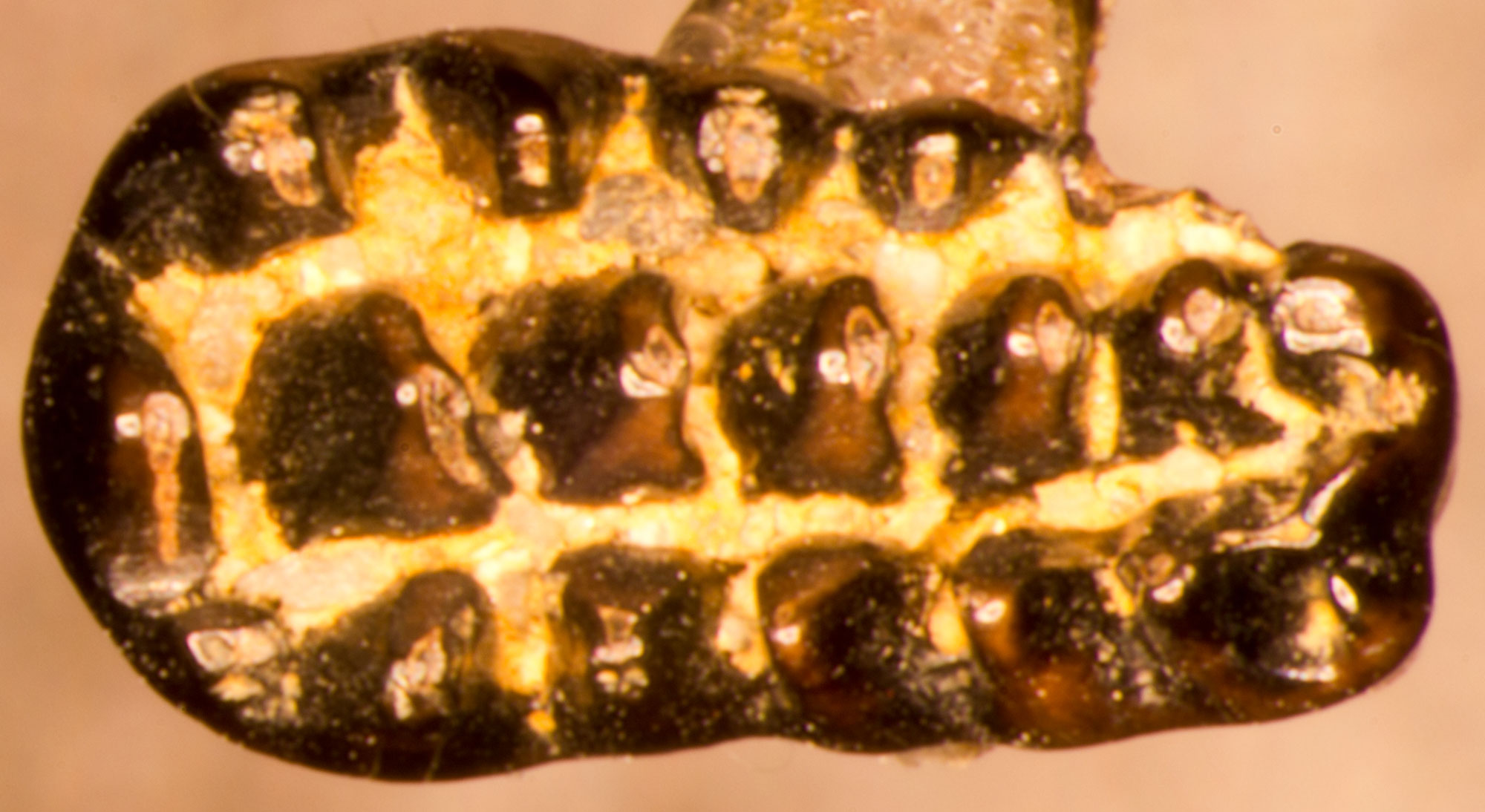

Tooth of a multituberculate mammal (Psalodon marshi), Jurassic Morrison Formation, Albany County, Wyoming. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

"Big Al" (Allosaurus fragilis), Jurassic Morrison Formation, Big Horn County, Wyoming. Specimen on display at the Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman, Montana. Photo by Tim Evanson (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

"Sophie" (Stegosaurus stenops), Jurassic Morrison Formation, Big Horn County, Wyoming. Specimen on display at the Natural History Museum, London. Source: From Fig. 1 in Maidment et al. (2015) PLoS ONE 10(10): e0138352 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image copyright The Natural History Museum).

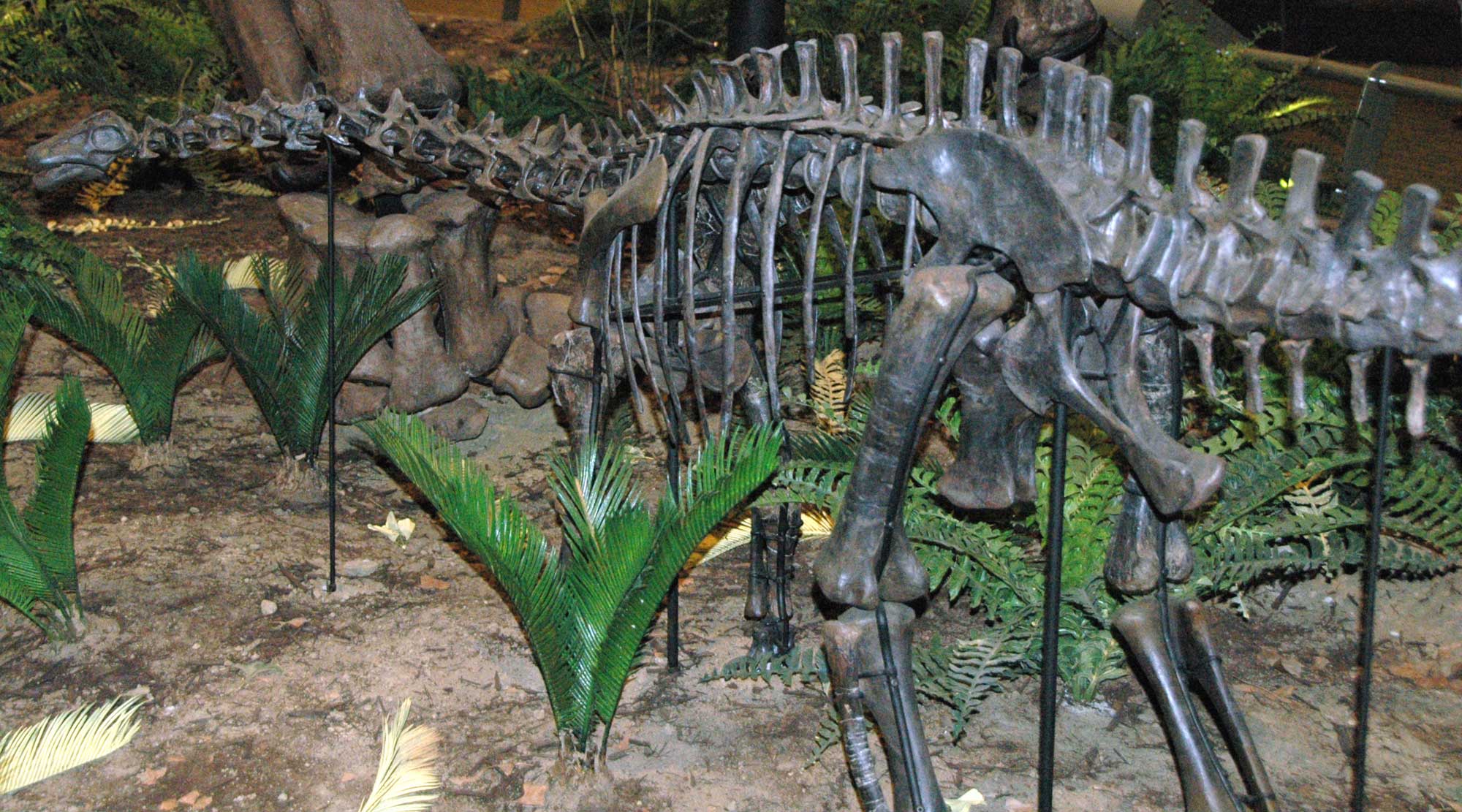

Juvenile Apatosaurus louisae, Jurassic Morrison Formation, Albany County, Wyoming. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

"Dippy" (Diplodocus carnegii) from the Jurassic Morrison Formation, Como Bluff, Wyoming. Specimen on display at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Casts (reproductions) of this skeleton are on exhibit at museums in Europe and Latin America. Photo by ScottRoberAnselmo (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Cretaceous fossils

Cretaceous marine fossils

Cretaceous marine rocks are well exposed in many parts of Wyoming, particularly around the edges of the Bighorn Basin. Notable fossils here include flat bivalves, such as Inoceramus, some of which reached enormous sizes, and heteromorph ammonoids including Didymoceras.

A snail (Campeloma nebrascensis) from the Lance Formation, Carbon County, Wyoming. Photo of YPM 536060 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

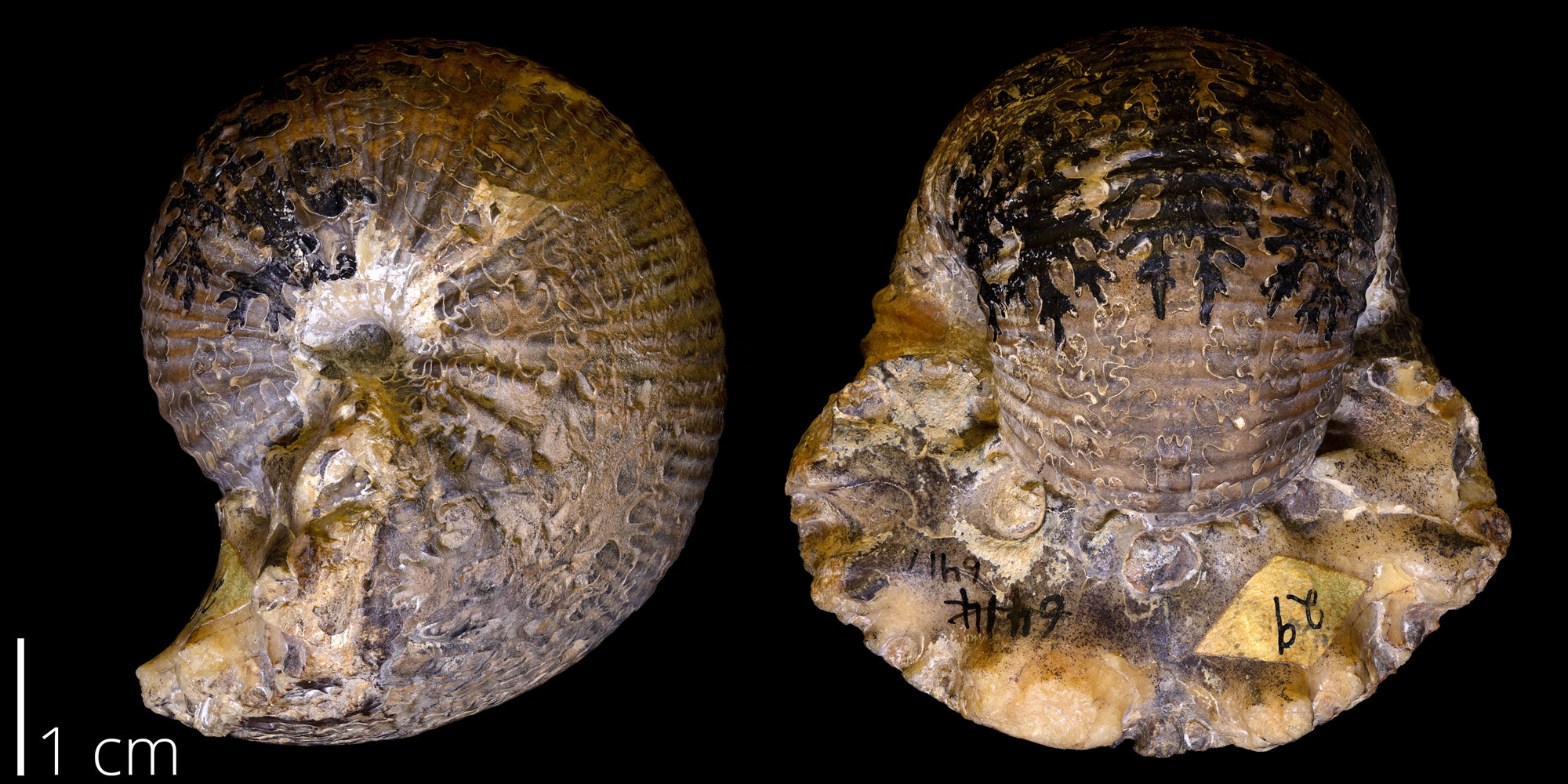

An ammonoid (Scaphites ventricosus) from the Frontier Formation, Park County, Wyoming. Photo of YPM 006417 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

An ammonoid (Plesiacanthoceras wyomingense) from the Cody Shale, Big Horn County, Wyoming. Photo of USNM PAL 431081 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, public domain).

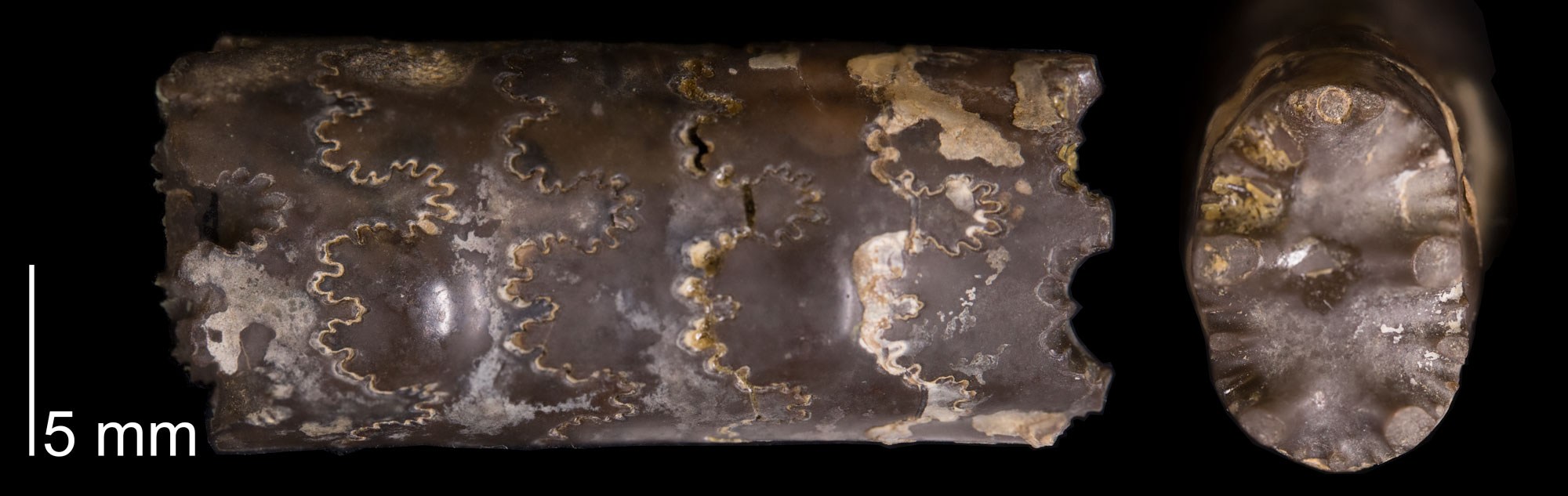

A baculite (Baculites asper), a straight-shelled ammonoid, from the Frontier Formation, Park County, Wyoming. Photo of YPM IP 6415 (Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Cretaceous terrestrial fossils

Fossils from the Early Cretaceous include those of fish, turtles, crocodilians, gastropods, bivalves, and plants. The enigmatic tree fern Tempskya has been found in eastern Idaho and in Wyoming, along with other plant fossils like palms.

A variety of dinosaur fossils (bone, teeth, and eggshell fragments) have been found from ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs), Ankylosaurus (an armored dinosaur with a clubbed tail), and theropods (predatory dinosaurs) are found in the Late Cretaceous. Late Cretaceous deposits of Idaho contain coal, leaves, and freshwater clams. Big Cedar Ridge Fossil Plant Area of Critical Environmental Concern, a site maintained by the Bureau of Land Management, preserves an important Late Cretaceous flora of the Meeteetse Formation in Wyoming.

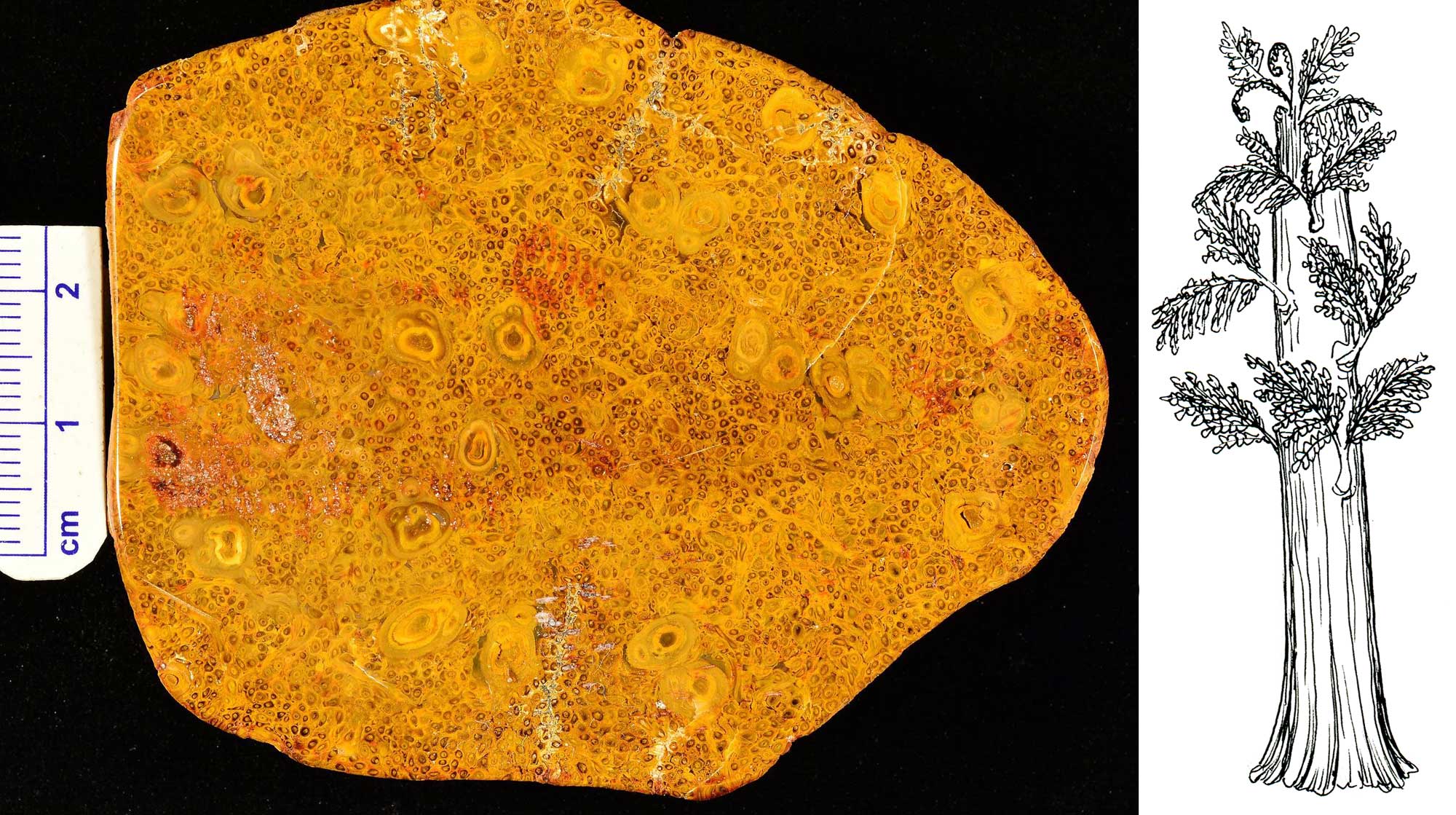

The tree fern Tempskya. Left: Cross section of a stem from the Cretaceous of Big Horn County, Wyoming. Right: Reconstruction of the living plant. Left photo of YPM PB 063567 by Robert Swerling (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication). Right drawing by Cristie Sobel, originally for The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Southwestern US.

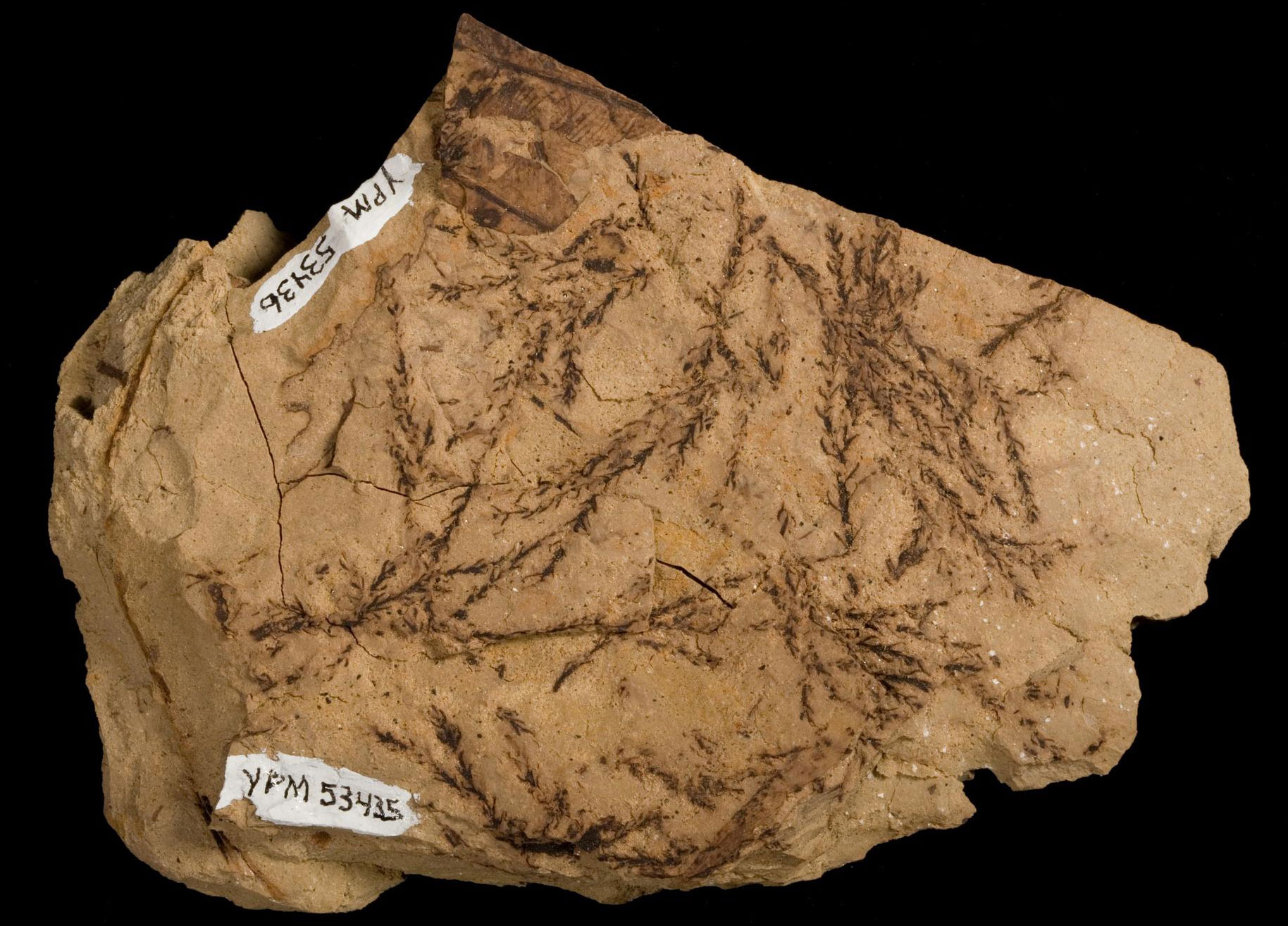

Chinese swamp cypress (Glyptostrobus europaeus) branchlets with leaves, Late Cretaceous Meeteese Formation, Park County, Wyoming. Photo of YPM PB 053435 Linda S. Klise, 2009 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Palm leaf, Big Cedar Ridge, Late Cretaceous Meeteese Formation, Wyoming. Photo of YPM PB 053449 by Division of Paleobotany (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Cenozoic fossils

Paleogene fossils

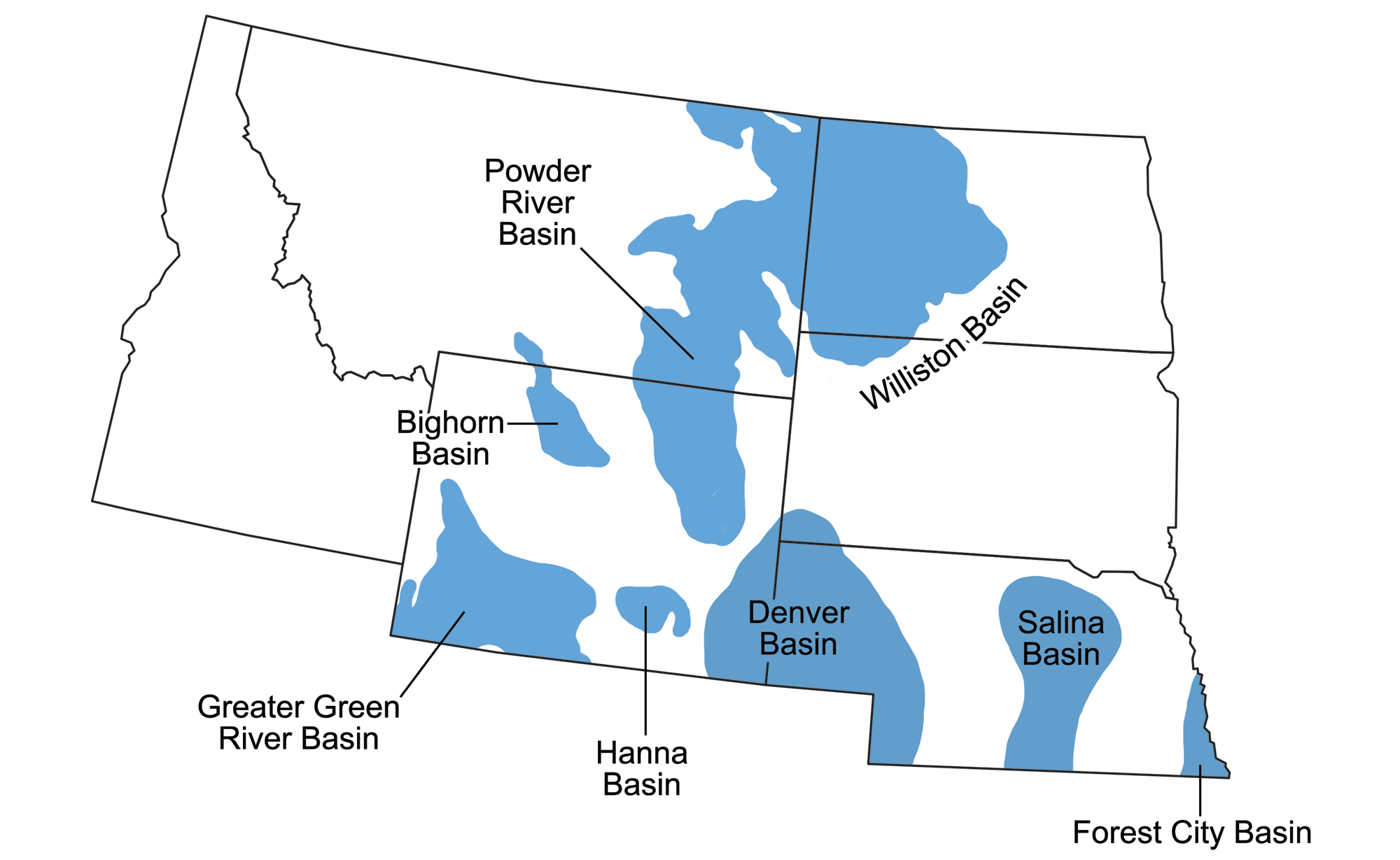

The early and mid-Cenozoic was a time of significant tectonic activity in the northwest-central States. During the Paleogene, the Western Interior Seaway advanced across the continent for the final time before tectonic uplift caused it to drain away. Nevertheless, extensive sedimentary deposits represent lakes, rivers, and floodplains. The uplift of mountain ranges to the west was a source of sediment that was transported and deposited by rivers in basins throughout the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain regions.

Cenozoic rocks preserve a fossilized view of ecosystems dramatically different from those of the Cretaceous. The dinosaurs disappeared, and mammals replaced them as the dominant large vertebrates on land. The warm, humid climate allowed the growth of lush forests. Plants that grew in these forests, including magnolia, ginkgo, sequoia and cypress, were preserved as the coal that is mined today in places such as Wyoming. Lakes were widespread, and were sites of deposition for thick, organic-rich sediments.

Sedimentary basins of the Northwest Central. Map by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northwest Central US.

Green River Formation

The Eocene Green River Formation is made up of thick layers of brown to cream-colored shale 600–2000 meters (1970–6560 feet) thick, with occasional layers of chert, limestone, and evaporites. It outcrops across a large area of southwest Wyoming, northwest Colorado, and northwest Utah, and composes the largest known accumulation of lacustrine sedimentary rock in the world.

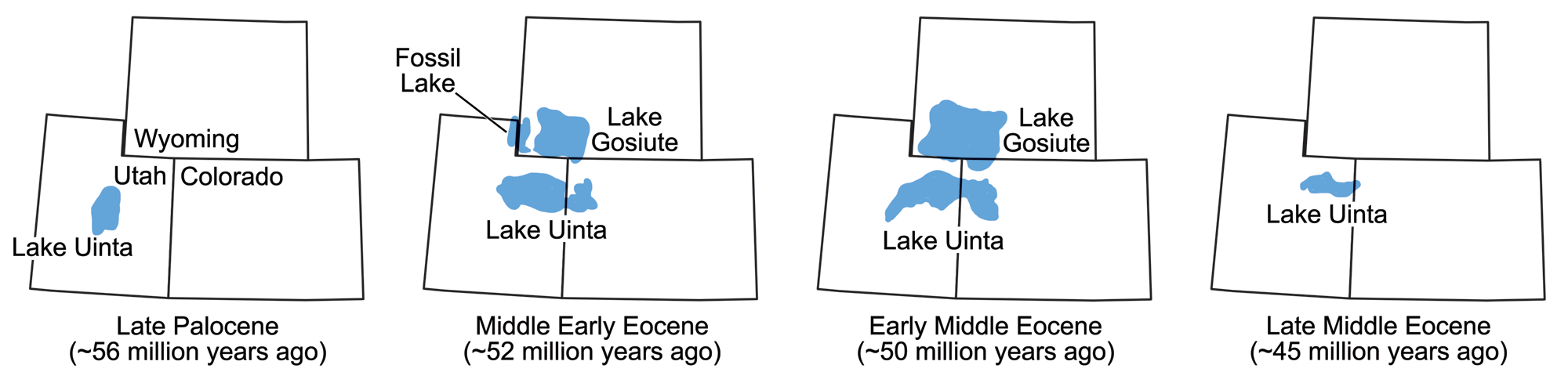

The sediments of the Green River Formation accumulated in a system of large lakes during the Eocene, between 58 and 40 million years ago. In Colorado and Utah, sediments of the Eocene Green River Formation accumulated in ancient Lake Uinta and are preserved in the Piceance and Uinta Basins. A second lake, called Fossil Lake, occurred on the border of northeastern Utah and southwestern Wyoming; its sediments are preserved in the region of Fossil Butte National Monument in Wyoming. Sediments of a third lake, Lake Gosiute, are preserved in the Green River Basin in Wyoming. The Green River Formation lakes existed for differing amounts of time, with Fossil Lake existing for the shortest time and Lake Uinta the longest.

The size and location of various lakes in which the Green River Formation sediments were deposited during the Eocene epoch. Maps modified from maps by Wade Greenberg-Brand, originally published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, after figure 3 in L. Grande (2013) The Lost World of Fossil Lake.

Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming. The light-colored rock making up the upper part of the butte is part of the Green River Formation and was deposited in Fossil Lake. The red rocks are part of the older Wasatch Formation. Photo by J.R. Hendricks and E.J. Hermsen (DEAL).

The Green River Formation is famous for the great number of well-preserved fossils found in its lake sediments, especially aquatic organisms, including stromatolites, mollusks, crayfish, turtles, alligators, and numerous fish. Well-preserved specimens of the fish Knightia are commonly found in the Green River Formation, and it is one of the most abundant vertebrate fossils in the world. A member of the herring family, the average Knightia is 7–12 centimeters (3–5 inches) long. Knightia is thought to have fed on algae, tiny crustaceans, and insects; in turn, it was a major source of food for many of the larger fish in these Eocene lakes. They are commonly found in mass mortality or “death bed” layers because they swam in schools.

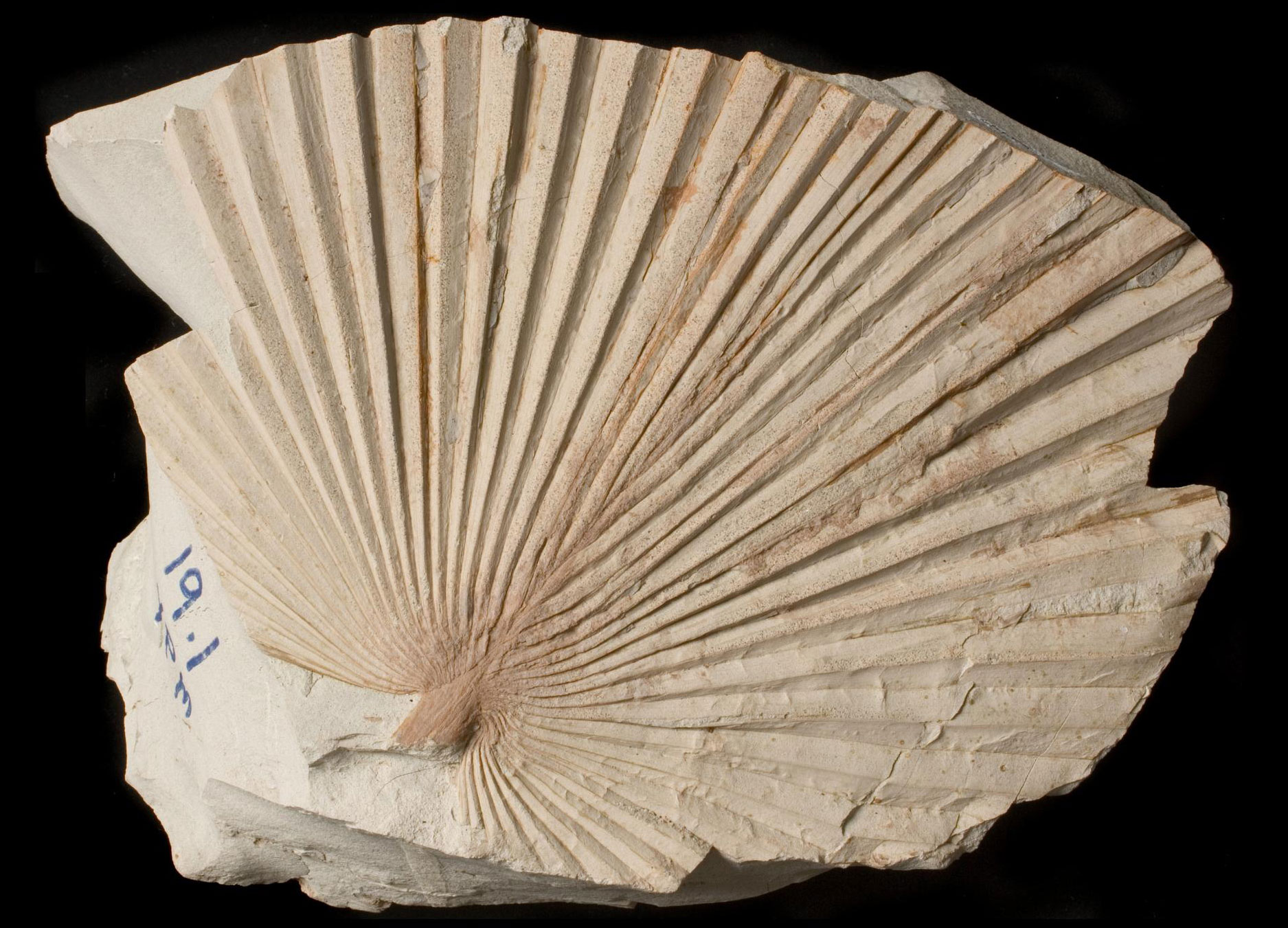

Many terrestrial animals are also preserved, including insects, birds, and terrestrial mammals. Green River plants include horsetails, water ferns, terrestrial ferns, conifers, and angiosperms, perhaps most notably spectacular palm leaves (Sabalites powellii). Green River Formation specimens are on display at many museums in the United States. Many specimens from Fossil Lake in particular are on display at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.

Fossils from ancient Lake Gosiute, Wyoming. Left. A stromatolite, a layered structure made by mats of cyanobacteria (sometimes called blue-green algae). Right: A rock known as "turritella agate," which is really a chert preserving a non-turritellid snail (Elimia tenera). Left photo and right photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, images cropped and resized).

Slab showing mass mortality of Knightia eocaena, a freshwater fish similar to a herring, Fossil Lake, Wyoming. Photo by National Park Service (public domain).

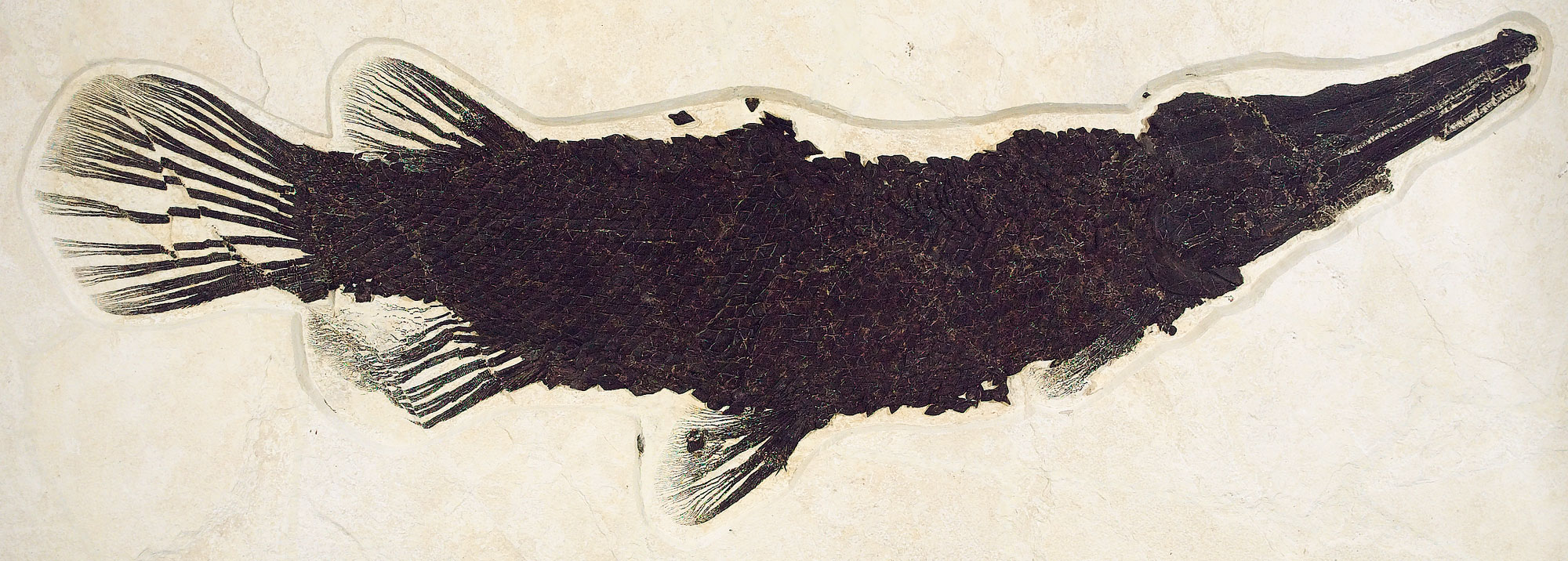

Eocene needle-nose gar (Lepisosteus bemisi), Fossil Lake, Wyoming. Photo by National Park Service (public domain).

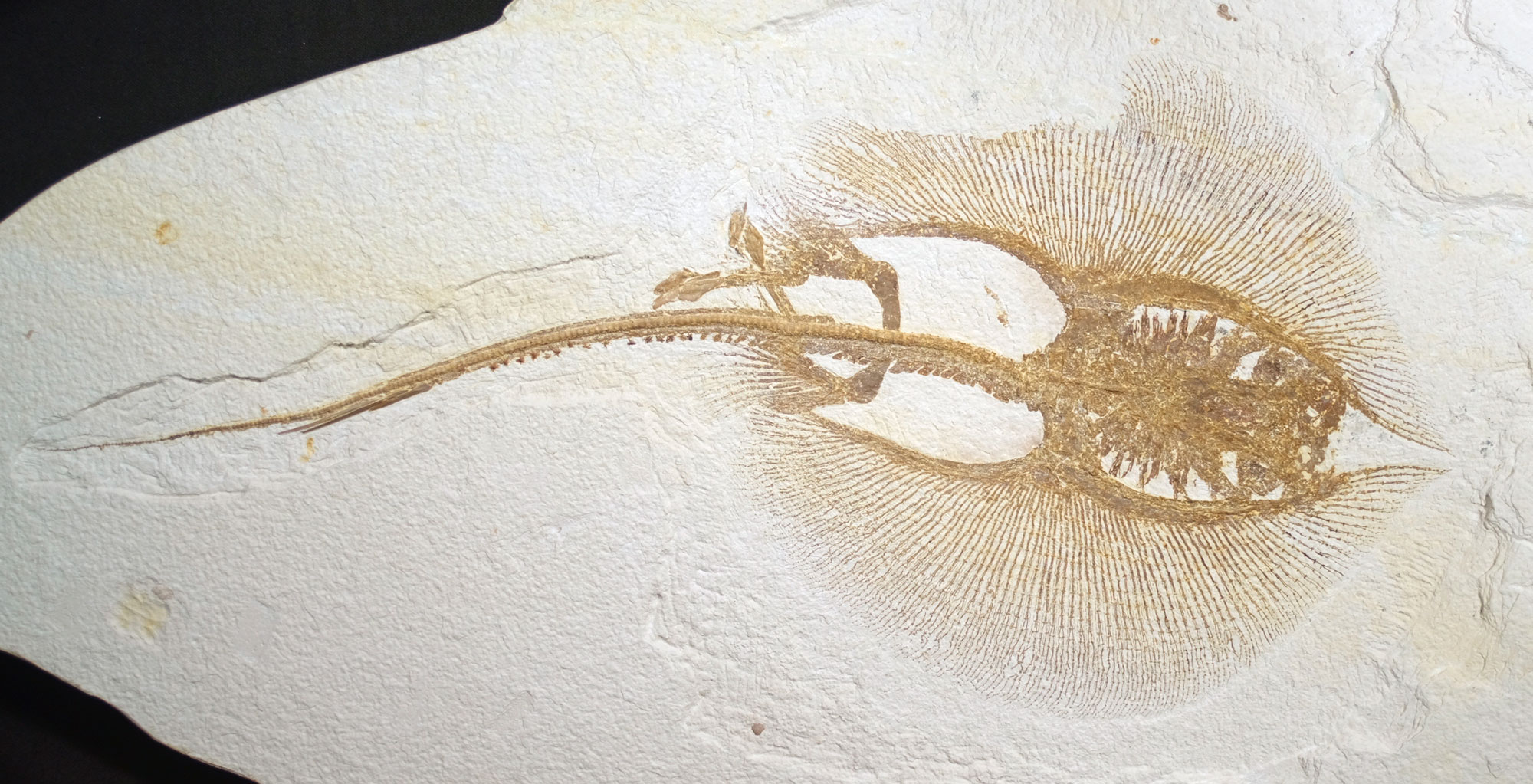

Eocene fat-tailed stingray (Heliobatis radians), Green River Formation, Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming. National Park Service photo (public domain).

A crocodile (Borealosuchus wilsoni), Fossil Lake, Wyoming. Specimen on display at the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, Illinois). Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

A fossil bird (Primobucco mcgrewi) similar to a modern roller, Fossil Lake, Wyoming. Photo by National Park Service (public domain).

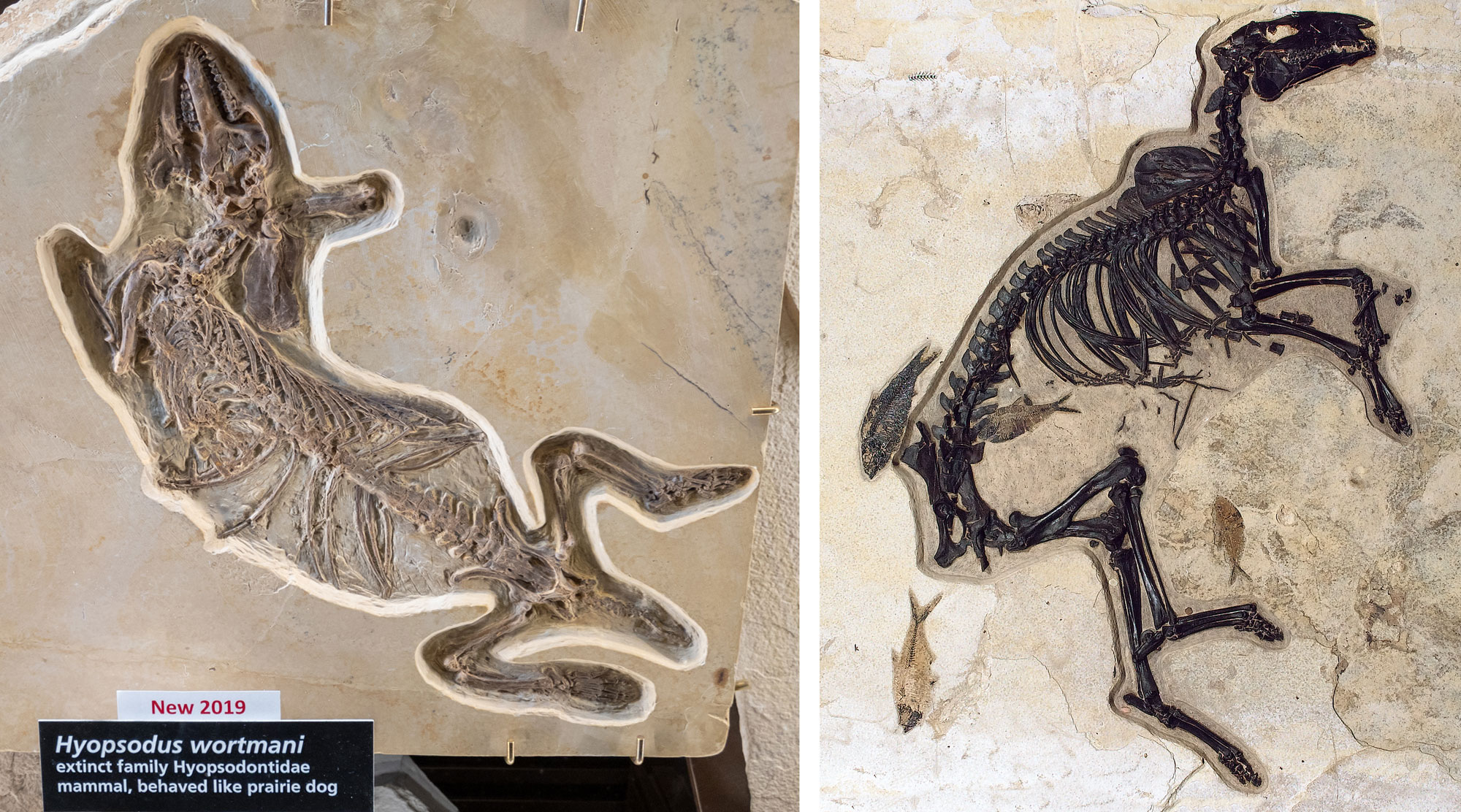

Land mammals from Fossil Lake on display at Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming (these specimens are casts, or reproductions of the original fossils). Left. A tube-sheep (Hyopsodus wortmani), an omnivore from an extinct group of mammals called condylarths. Right: An Eocene horse (Protorohippus venticolus). Photo of Hyopsodus wortmani by Matthew Dillon (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized). National Park Service photo of Protorohippus venticolus (public domain).

Fossil bat from Fossil Lake discovered in 2021. Photo by National Park Service (public domain).

Left: Large palm leaf (Sabalites powellii) with fossil fish, Fossil Lake. Specimen on display at the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, Illinois). Right: Display of plant fossils from Fossil Lake at Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming. Left photo by E.J. Hermsen; right photo by J.R. Hendricks and E.J. Hermsen.

Yellowstone Petrified Forest

The Eocene was a time of extensive volcanism in the Rocky Mountain region. This is reflected in the occurrence of silica-rich layers in the Green River Formation, which formed from weathered volcanic ash, as well as the famous Yellowstone Petrified Forest. This extraordinary assemblage of multiple layers of volcanic ash contains numerous upright-standing, petrified tree trunks and abundant transported logs and stumps. It formed when ash was repeatedly eroded off of volcanoes and re-deposited in braided streams and rivers.

Upright petrified tree trunks at Specimen Ridge, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Photo by Jacob W. Frank, NPS (Yellowstone National Park on flickr, public domain).

Petrified stump, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Photo by Jacob W. Frank, NPS (Yellowstone National Park on flickr, public domain).

Neogene fossils

Clarkia Fossil Beds

Abundant Miocene plant remains can also be found in northern Idaho (Shoshone and surrounding counties), where an ancient lake (approximately 15 million years old) provided ideal conditions for the fossilization of soft plant parts. Fossils in the Miocene Clarkia Fossil Beds are so well preserved that some leaves even retain their original color; most are yellow, orange, and brown since they were shed during fall months, although they rapidly oxidize and turn black when exposed to air. The lake formed when a basin was dammed by basalt flows on the Columbia River Plateau.

Although best known for its plants, the Clarkia Beds also contain well-preserved fossil fish, snails, insects, and a rare mammal. Like most lagerstätten (exceptionally well preserved fossil beds), the Clarkia Beds probably formed in a low-oxygen sedimentary environment, which slowed decay of the organic remains.

Leaf of a stone oak (Lithocarpus) from the Miocene Clarkia flora of Idaho. Photo of YPM PB 049087 by Linda S. Klise, 2009 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural history on GBIF, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Fossil squirrel, Miocene Latah Formation, Clarkia Fossil Beds, Idaho. Source: From Figure 3 in Calede et al. (2018) PeerJ 6:e4880 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern United States: Fossils of the Rocky Mountains (covers the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/fossils-rm

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Western United States: Fossils of the Rocky Mountains (continues coverage of the Rocky Mountains in northeastern Washington): https://earthathome.org/hoe/w/fossils-rm

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/