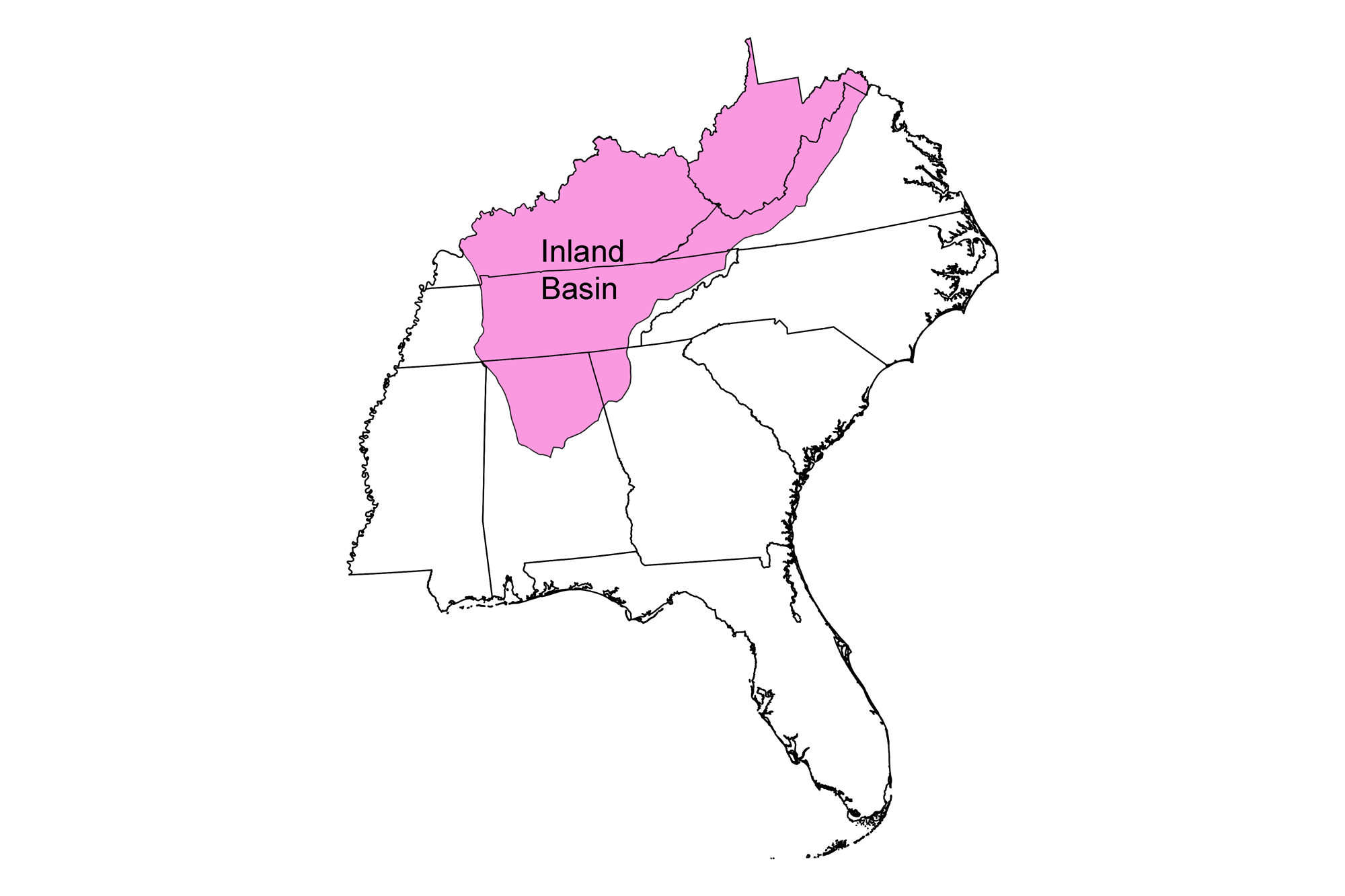

Snapshot: Metallic and non-metallic mineral resources in the Inland Basin region of the southeastern U.S. Coverage also includes selected non-mineral resources the are commercially mined or quarried (for example, building stone).

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; Metallic mineral resources; Non-metallic mineral resources; Resources (references and further reading about minerals).

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Mineral resources of the Southeastern US" by Robert J. Moye, Stephen F. Greb, and Jane A. Picconi, chapter 5 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S., 2nd ed., edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated February 25, 2022.

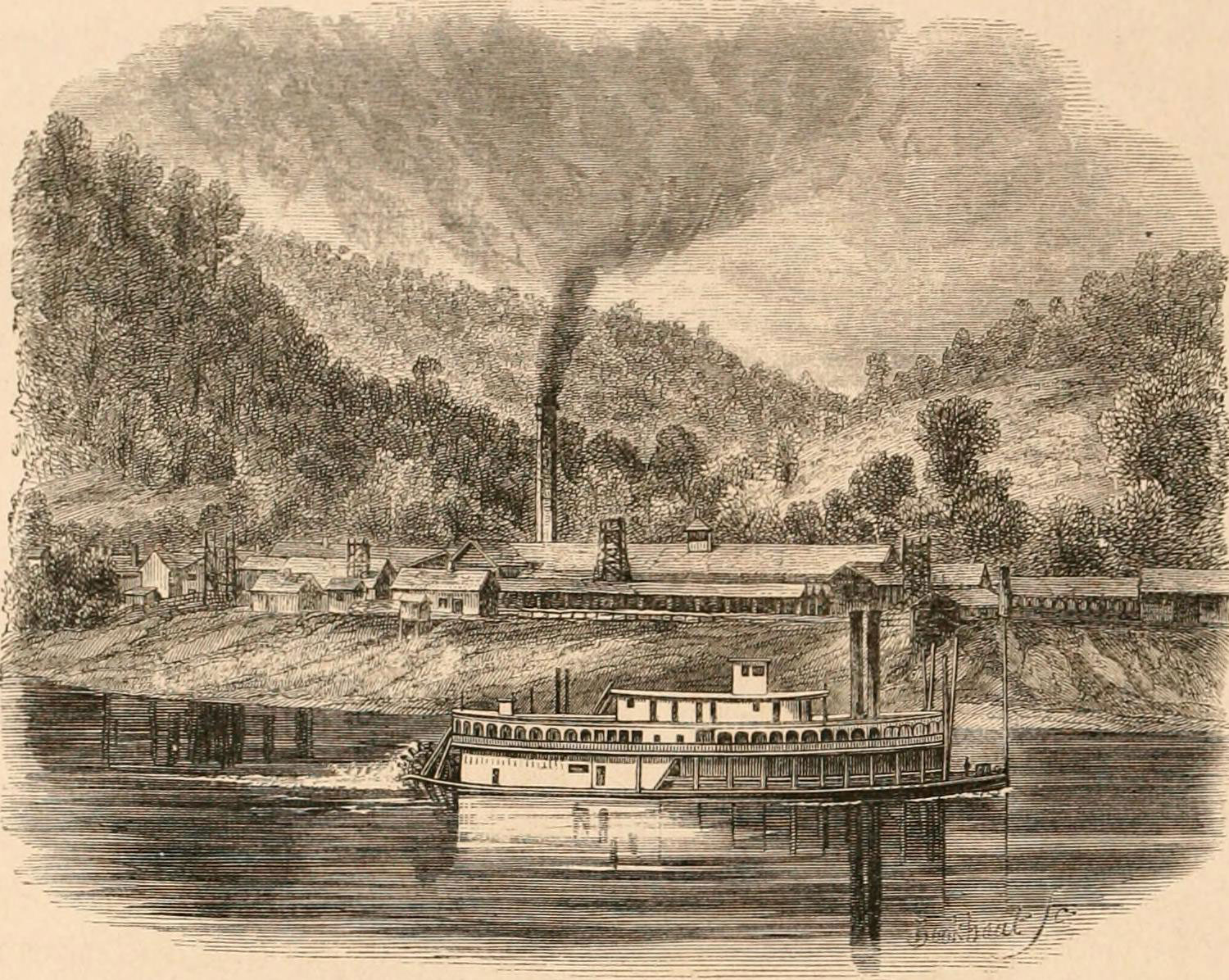

Image above: Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron, showing No. 1 Furnace; Birmingham, Alabama. Image by Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

Introduction

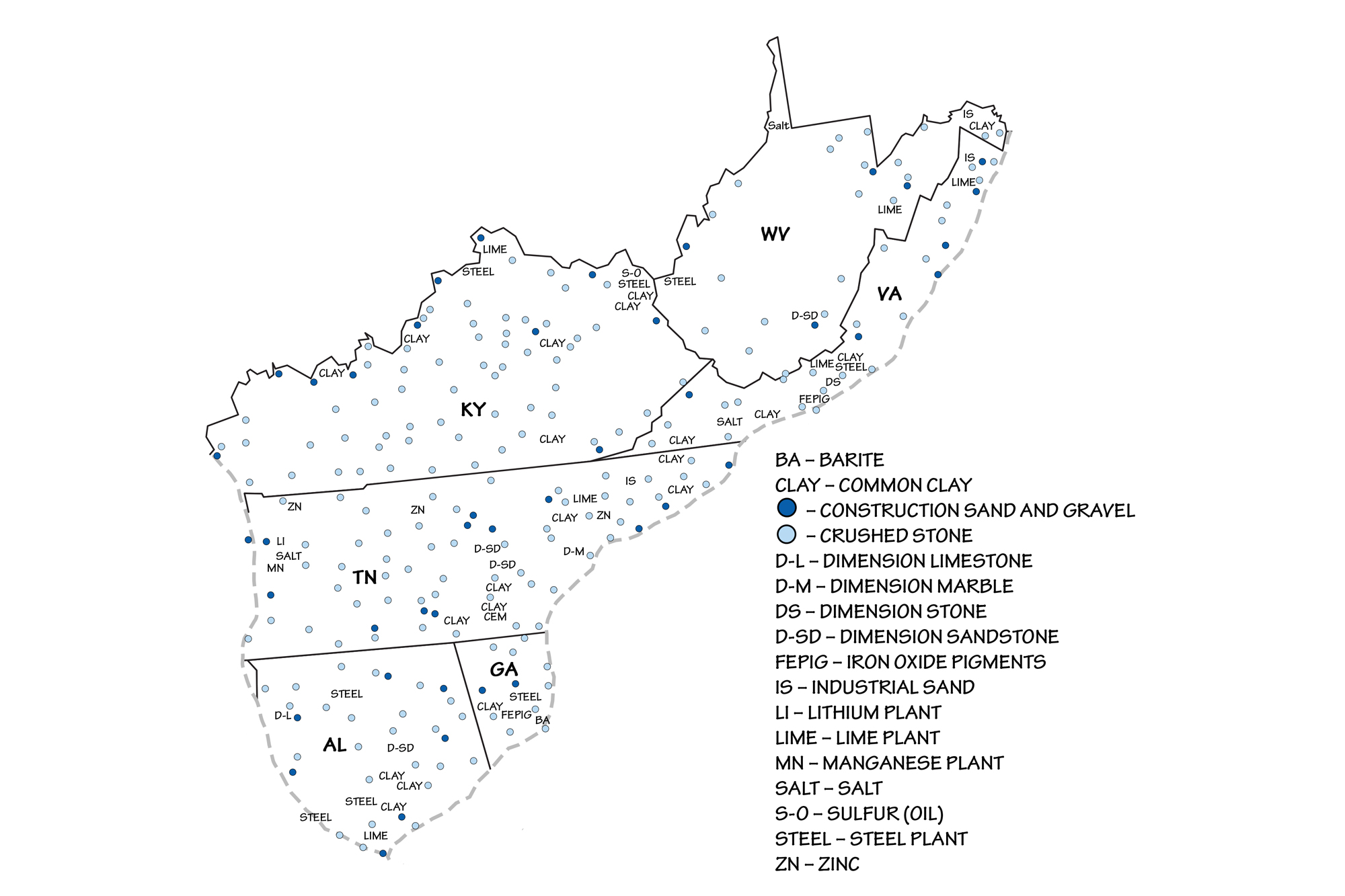

The major mineral deposits of the Inland Basin include sulfide and non-sulfide minerals associated with hydrothermal processes.

Occurrences of lead and zinc are widespread throughout much of the Appalachian Basin and Valley and Ridge, where thrust faults and fractures provided pathways for fluid migration and sites for ore deposit formation during the Acadian and Alleghanian orogenies to the east.

In addition, a vast reservoir of sedimentary rocks was deposited in the Paleozoic inland sea that covered the western half of the Inland Basin. Extensive precipitation of evaporite salts in this shallow sea occurred during the Silurian, and locally at other time periods. Weathering and erosion have also been important processes in the formation of mineral deposits in the Appalachian Basin. Chemical weathering of limestone and dolostone have formed numerous small deposits of iron, manganese, and bauxite at the surface, and concentrated lower-grade hydrothermal deposits of barite.

Metallic mineral resources

Lead and zinc

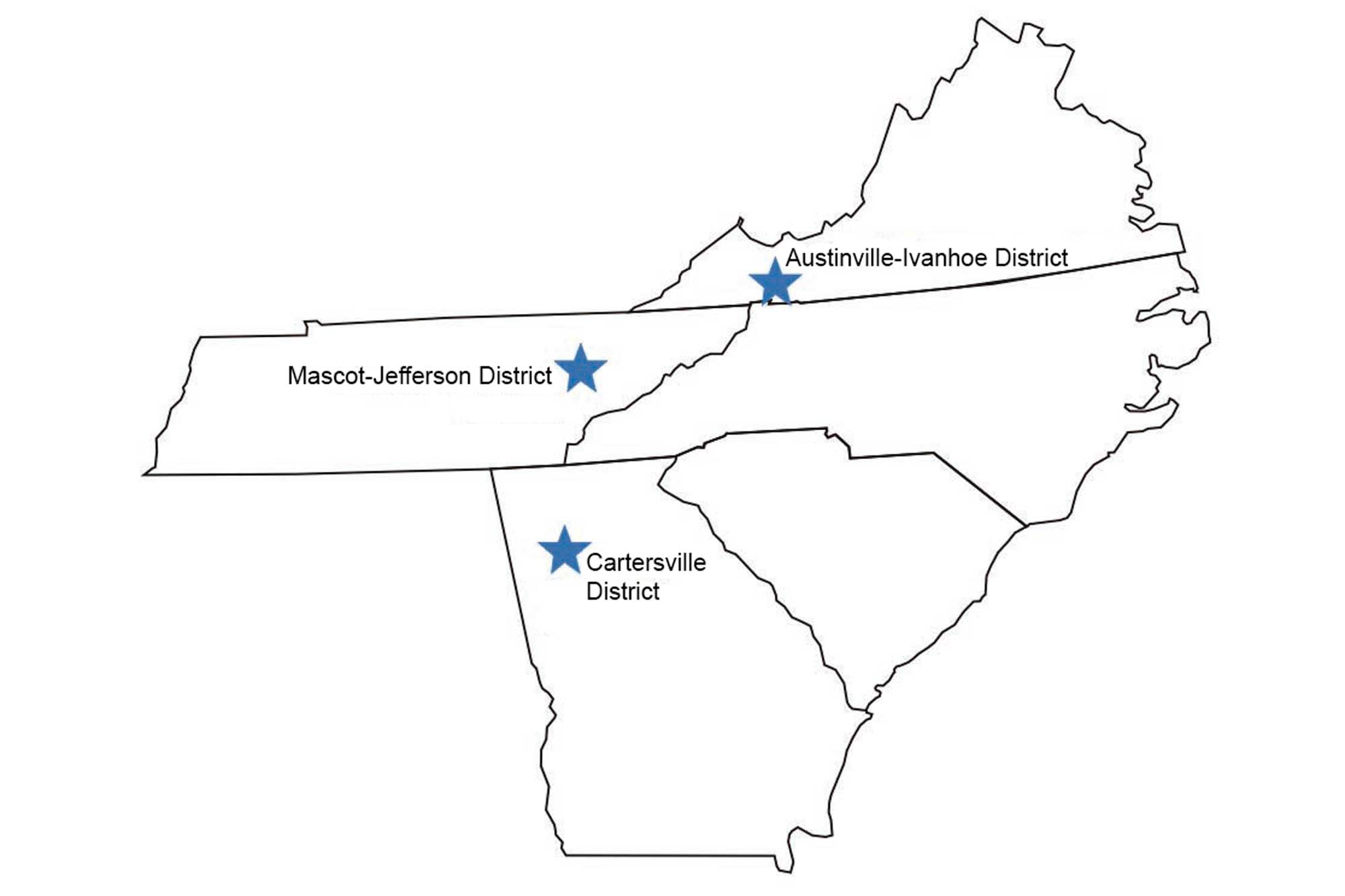

Extensive deposits of lead, zinc, fluorite, and barite minerals occur in Cambrian and Ordovician dolostones along the eastern margin of the Valley and Ridge from south of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, through western Virginia and eastern Tennessee, and into northern Georgia. These deposits generally developed as a result of hydrothermal fluids migrating through zones of higher permeability, karst, fractures, and faults. They vary widely in their relative proportions of lead and zinc sulfides, pyrite and chalcopyrite, and fluorite and barite. Important mining districts include the Mascot-Jefferson District in Tennessee and the Austinville-Ivanhoe District in Virginia.

Significant lead, zinc, fluorite, and barite deposits are found in Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia. Image by Jim Houghton, modified for the Earth@Home project.

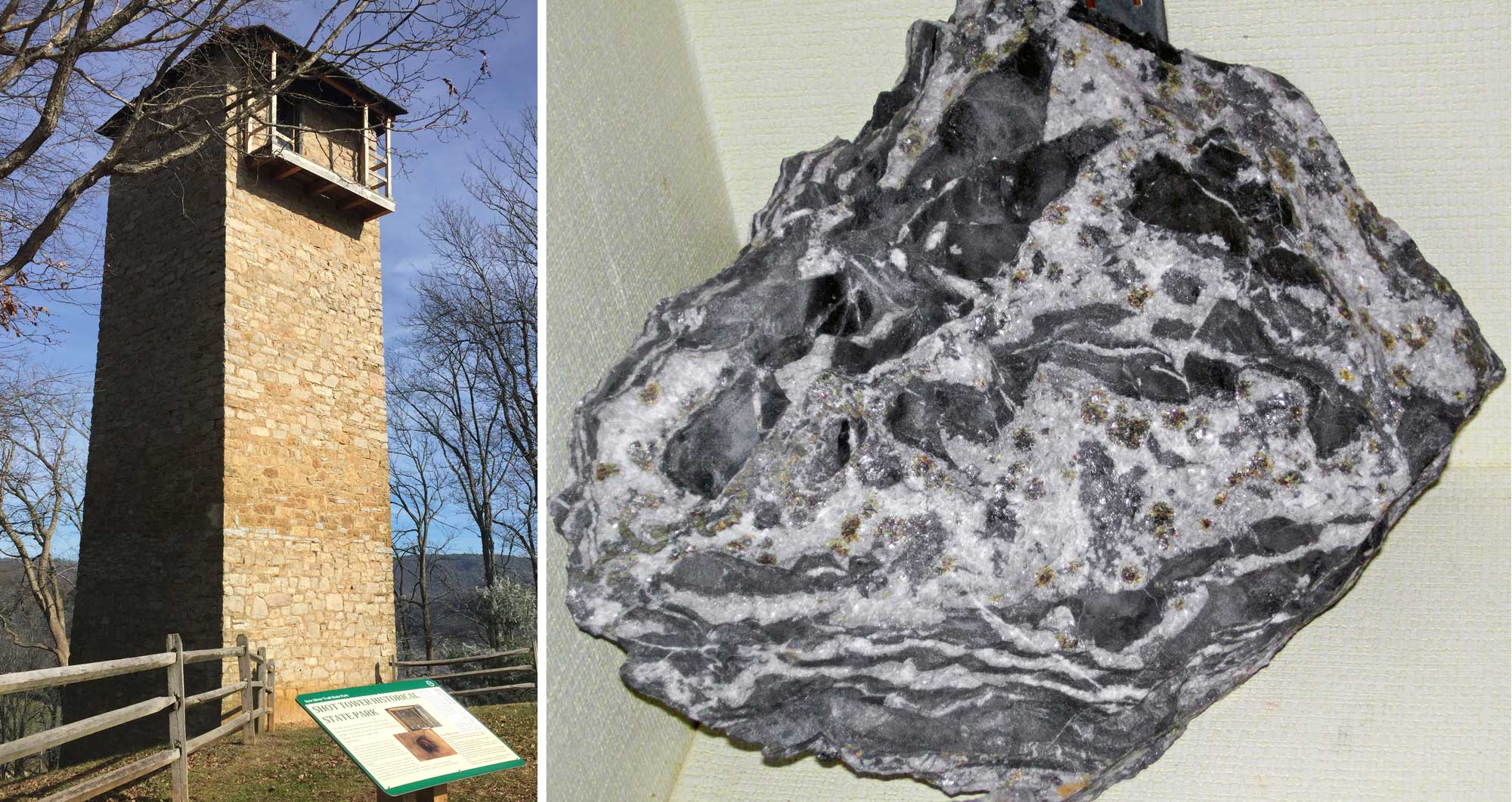

The lead and zinc works in southern Wythe County, Virginia (in the Austinville-Ivanhoe District), played a vital role in two early chapters in United States history. The Wythe County lead mines were opened in 1756 by Colonel John Chiswell, a British officer who discovered the lead deposits. The mines were an important source of lead shot ammunition for the Colonial Army during the American Revolution, and the workings were expanded from 1775 to 1781 to meet the growing demand of the Continental Army.

The Wythe County mines were also a critical resource for the Confederacy during the Civil War—reports suggest that about 1.6 million kilograms (3.5 million pounds) of lead for bullet-making were produced at the mines during the Civil War, accounting for one-third of the estimated 4.5 million kilograms (10 million pounds) of lead consumed by the entire Confederacy in the manufacture of 150 million cartridges. Production ended on December 31, 1981, when the New Jersey Zinc Company permanently closed the mine, ending its 225-year run.

The last of Virginia's lead and zinc mines closed in 1984, but mining continues in eastern Tennessee, and barite is still extracted from lower grade lead-zinc deposits of the Cartersville District in northern Georgia.

Austinville-Ivanhoe mining region, Wythe County, Virginia. Left: Shot Tower is a 75-foot-tall (about 23 meters tall) structure that dates to 1807 and that was used to make lead shot with lead from nearby mines. The shot was made by dropping molten lead through a sieve at the top of the tower into a deep shaft underneath, where it landed in a container of water. The total drop was 150 feet (about 46 meters). Photo by Laura A. Macaluso, Ph.D. (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized). Right: Lead-zinc ore (sphalerite-galena-dolomite), Austinville-Ivanhoe Mine, Austinville, Virginia. Photo and information from James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Iron ore

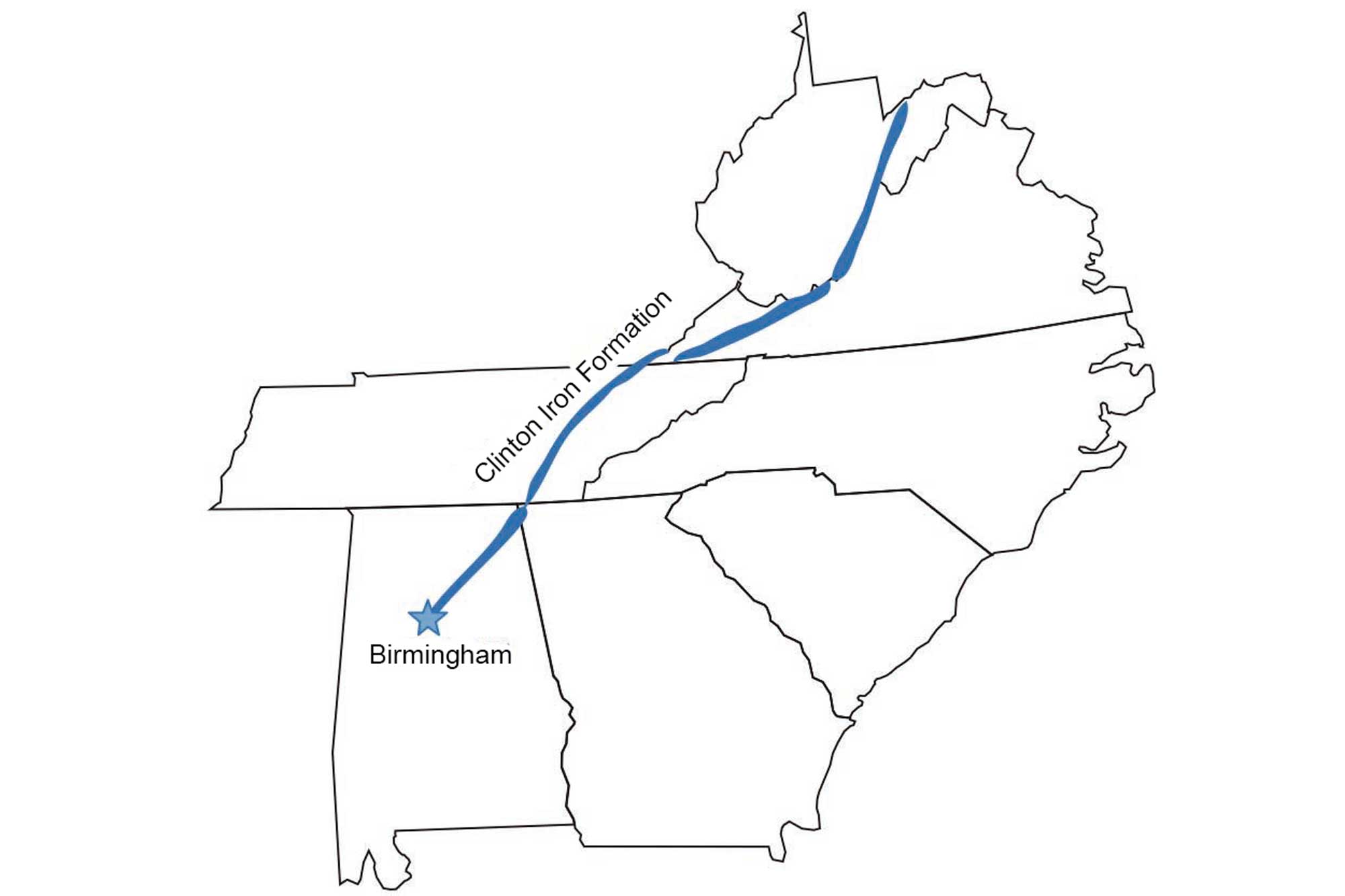

Widespread deposits of sedimentary iron in the Inland Basin range in age from Cambrian to Pennsylvanian. The most extensive iron ore deposits in the Southeast are the middle Silurian Clinton Formation deposits (and their equivalents) that extend along the eastern side of the Appalachian Basin from New York to Alabama.

The Clinton Iron Ore Formation extends through several southeastern states along the Appalachian Basin. Image by Jim Houghton, modified for the Earth@Home project.

Iron weathered from the eroding Taconic Mountains was deposited in various forms along the edge of the ancient seaway to the west, and occurs as oxides, carbonates, and silicates in sandstones, shales, and limestones. Weathering increases the grade of the ores and makes them more easily mined. The Clinton iron ores are especially rich and thick near Birmingham, Alabama, where the dominant iron mineral is hematite. These iron deposits made Birmingham a major center of steel production, and about 375 million tons of hematite ore were mined there between 1840 and 1975.

The success of the iron and steel industry around Birmingham was due to the thick, high-grade nature of the Clinton iron ore deposits, the close proximity of deposits of Pennsylvanian coal to fuel the blast furnaces, and the use of Cambrian and Ordovician limestone and dolostone as flux for smelting.

The Sloss Furnaces National Historic Site in Birmingham, Alabama. The site was constructed in 1881, and by the end of its fi rst year of operation it had sold 24,000 tons of iron. Most of the buildings and structures remaining on the site today date from 1900–1914. Sloss is the only 20th-century blast furnace preserved in the U.S. as a historic industrial site. Photograph by Ron Cogswell (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Numerous small secondary iron deposits occur throughout the Inland Basin. Most are the products of weathering, formed when iron oxide was concentrated as residuum from carbonate rocks that were chemically weathered and eroded away.

Some iron deposits are gossans, residual iron oxide deposits formed by the weathering of sulfide deposits at the surface. Small deposits of both types were mined in every state in the Southeast during the 1700s and 1800s to supply local forges that turned out small quantities of iron and steel for local markets. The first iron furnaces in the Southeast were built around 1765 in Virginia. Small furnaces appeared in North Carolina in 1780, Tennessee, and West Virginia in 1790, Kentucky in 1791, and Alabama in 1815.

Historical iron furnaces in Kentucky. Left: Bourbon Iron Furnace, Owingville, built in 1791. Photo uncredited (Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress, no known restrictions on images made by the U.S. government). Right: Fitchburg Furnace, Estill County, built in 1868. Photo by PEO ACWA (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Non-metallic mineral resources

The Inland Basin's industrial minerals are some of its most valuable nonmetallic resources.

Sand, gravel, and crushed stone

Sand and gravel is used for aggregate, and common clay is collected for use in brick making. Paleozoic limestone and dolomite (dolostone), which form the bedrock across much of the Inland Basin, are quarried for crushed stone throughout the region. The Reed Quarry in Kentucky is one of the largest producers of crushed stone in the United States, and crushed stone has been Tennessee's leading mineral commodity (by value) for over 25 years. Most of this crushed stone is used for construction aggregate and for the production of lime and cement.

Once considered a waste byproduct of crushed stone, lime has important uses in agriculture, where it is regularly applied to make the soil "sweeter" (less acidic). Lime is also used in steel making, water purification, sulfur removal from smoke stacks, sewage treatment, and paper manufacturing. Alabama and Kentucky are two of the top lime-producing states in the nation.

Local dimension sandstone and industrial sandstones are quarried in the eastern part of the region, within the Valley and Ridge. The quartz-rich Tuscarora and Oriskany sandstones are commonly mined and crushed for use as industrial sand because they are 98% silica, and therefore useful for glass manufacturing. These stones, abundant in West Virginia, have made the state one of the nation's leading glass manufacturers. Some Mississippian and Pennsylvanian sandstones also contain natural bitumen, or tar. These tar sands historically have been quarried for the natural asphalt they contain.

Salt

Salt, a powerful antibacterial, was a critical commodity for curing butter and meats in the absence of refrigeration. Besides its use in food, salt is also used to clear roads and sidewalks of ice in northern climates.

Extensive evaporite deposits formed during the late Silurian in a shallow tropical sea at the northern end of the Appalachian Basin and are present below the surface in northern West Virginia. Natural brines present as ancient seawater trapped in porous sedimentary rocks (aquifers) are found throughout the Inland Basin and contain in excess of 15% dissolved salts within 610 meters (2000 feet) of the surface throughout eastern Ohio, western West Virginia, and northeastern Kentucky. Mississippian-aged halite (rock salt) deposits occur below the surface around Saltville, Virginia, where salt was first discovered in 1840 in a mineshaft at a depth of 66 meters (215 feet).

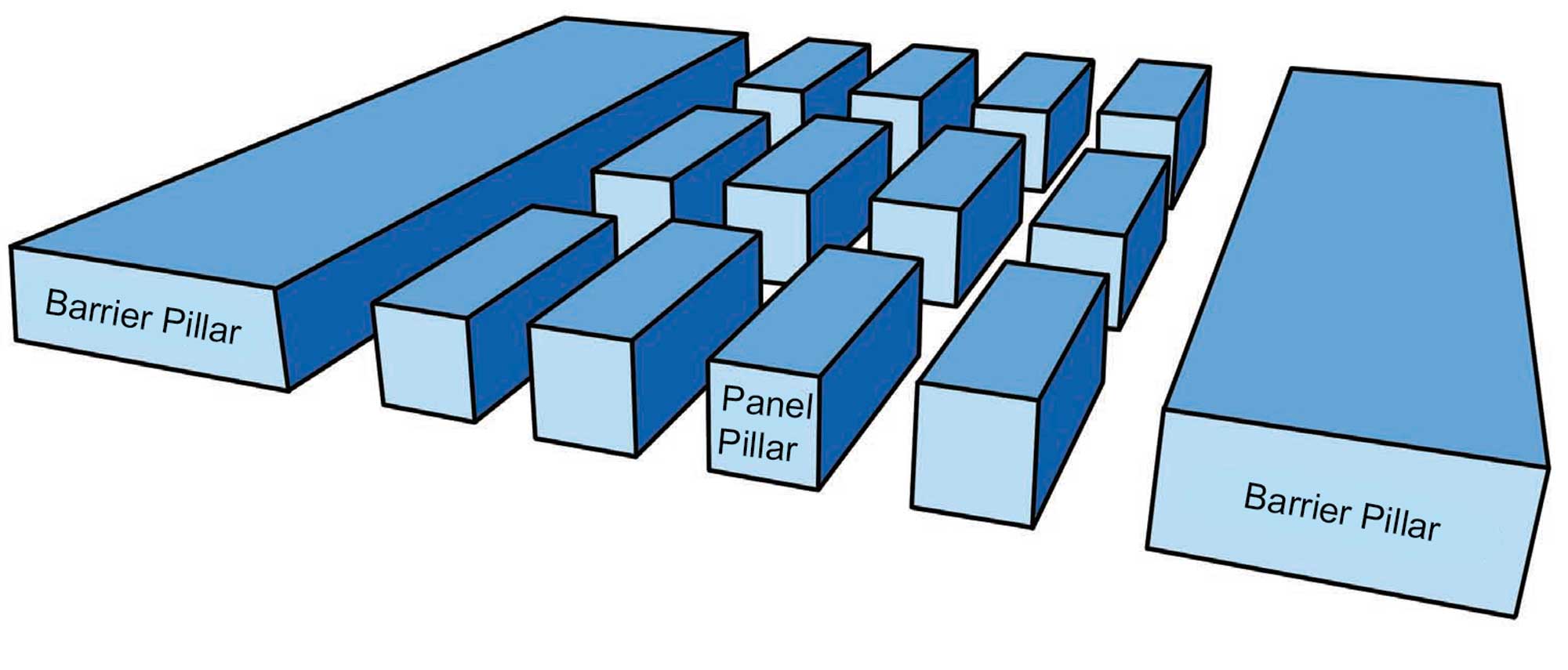

Halite is mined in two ways. When deposited in thick beds, this salt can be excavated by mechanically carving and blasting it out. This method, called "room and pillar" mining, usually requires that pillars of salt be left at regular intervals to prevent the mine from collapsing.

In pillar and room mining, the mine is divided up into smaller areas called "panels." Groups of panels are separated from one another by extra-large (barrier) pillars that are designed to prevent total mine collapse in the event of the failure of one or more regular-sized (panel) pillars. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, adapted from image by "Swinsto101" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license) and modified for the Earth@Home project.

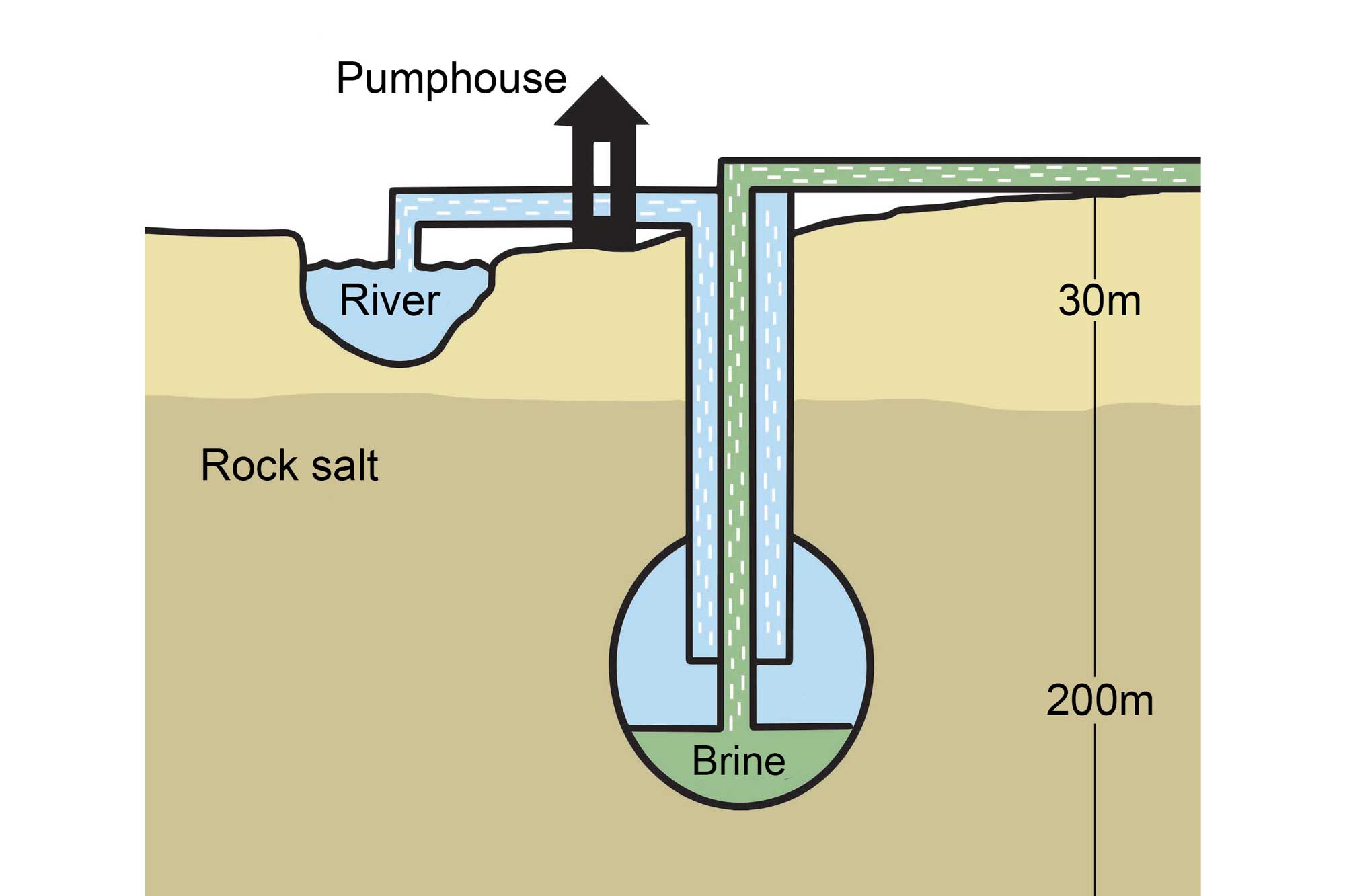

Another method, called solution mining, involves drilling a well into a layer of salt. In some cases, the salt exists as part of a brine that can then be pumped to the surface, where the water is then removed, leaving the salt behind. In others, fresh water is pumped down to dissolve the salt, and the solution is brought back to the surface where the salt is removed. In the Saltville area of western Virginia, rock salt is extracted by solution mining.

An example of solution mining that involves the pumping of fresh water through a borehole drilled into a subterranean salt deposit. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, adapted from image by the Salt Association and modified for the Earth@Home project.

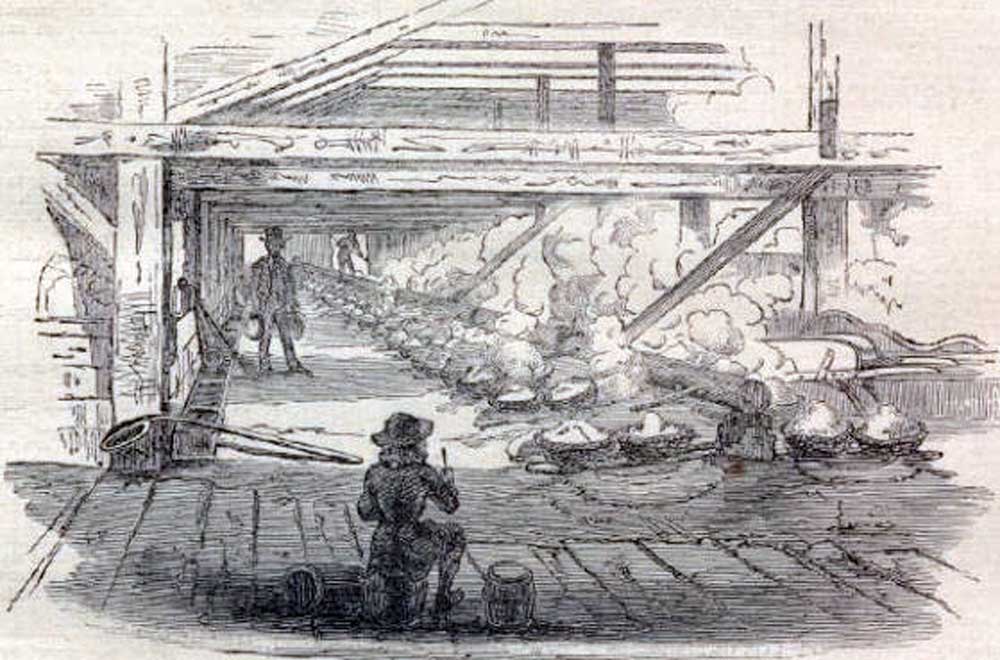

Natural brine springs in the Kanawha Valley, near Charleston, West Virginia, formed salt licks that were extensively utilized by animals and later exploited by Native Americans, who boiled the brine to obtain salt. The Kanawha Licks near the town of Malden, West Virginia, became the center of a major colonial salt industry in the early 19th century.

Although it represents only a small fraction of total U.S. salt production, the proximity of salt, coal, and petroleum resources with good railroad and river access has resulted in the growth of an extensive chemical industry in West Virginia along the Ohio River and in the Kanawha Valley, between Wheeling and Huntington. The Kanawha Valley salt industry reached a peak production of 113,638 cubic meters (3,224,786 bushels) in 1846, and was one of the largest salt manufacturing centers in the U.S.

This brine industry declined in importance after 1861, but it was revitalized thanks to demand for chemical products during World War I, with the 1914 opening of the Warner-Klipstein Chemical Company plant in South Charleston to produce chlorine and caustic acid. West Virginia hosts three principal salt-producing companies: two in Marshall County and one in Tyler County. Most of the area's salt is now used by a variety of chemical companies that have developed along the Kanawha River since that time. Today, the Westvaco Chlorine Products Corporation is the largest chlorine producer in the world.

This 1865 illustration depicts the boiling of brine-filled kettles to make salt during the Civil War. Image from Harper's Weekly (public domain).

This 1875 illustration depicts the Snow Hill Salt Works, Kanawha River, West Virginia. Illustration from E. King (1875) The Southern states of North America: a record of journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland, digitized by the Internet Archive (flickr, no known copyright restrictions).

Douglas “diamonds”

Douglas Lake in Jefferson County, Tennessee, is known for distinctive quartz crystals called "Douglas Diamonds." During periods of water fluctuation, when expanses of the lake bottom are exposed, these crystals can be found scattered across the dry surface. The quartz precipitated from silica-rich hydrothermal solutions that flowed through fractures in the region's limestone and calcite bedrock; later weathering eroded the surrounding rock to expose these more resistant crystals. These quartz “diamonds” are not mined for industrial or commercial purposes, but are collected recreationally by rockhounds.

"Rockhounding Family Adventures Lake Douglas Diamonds Episode 5 season 1" by Rockhounding Family Adventures (YouTube).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life: Minerals (collection of 3D models on Sketchfab): https://skfb.ly/6WxTo

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals: https://earthathome.org/de/minerals/