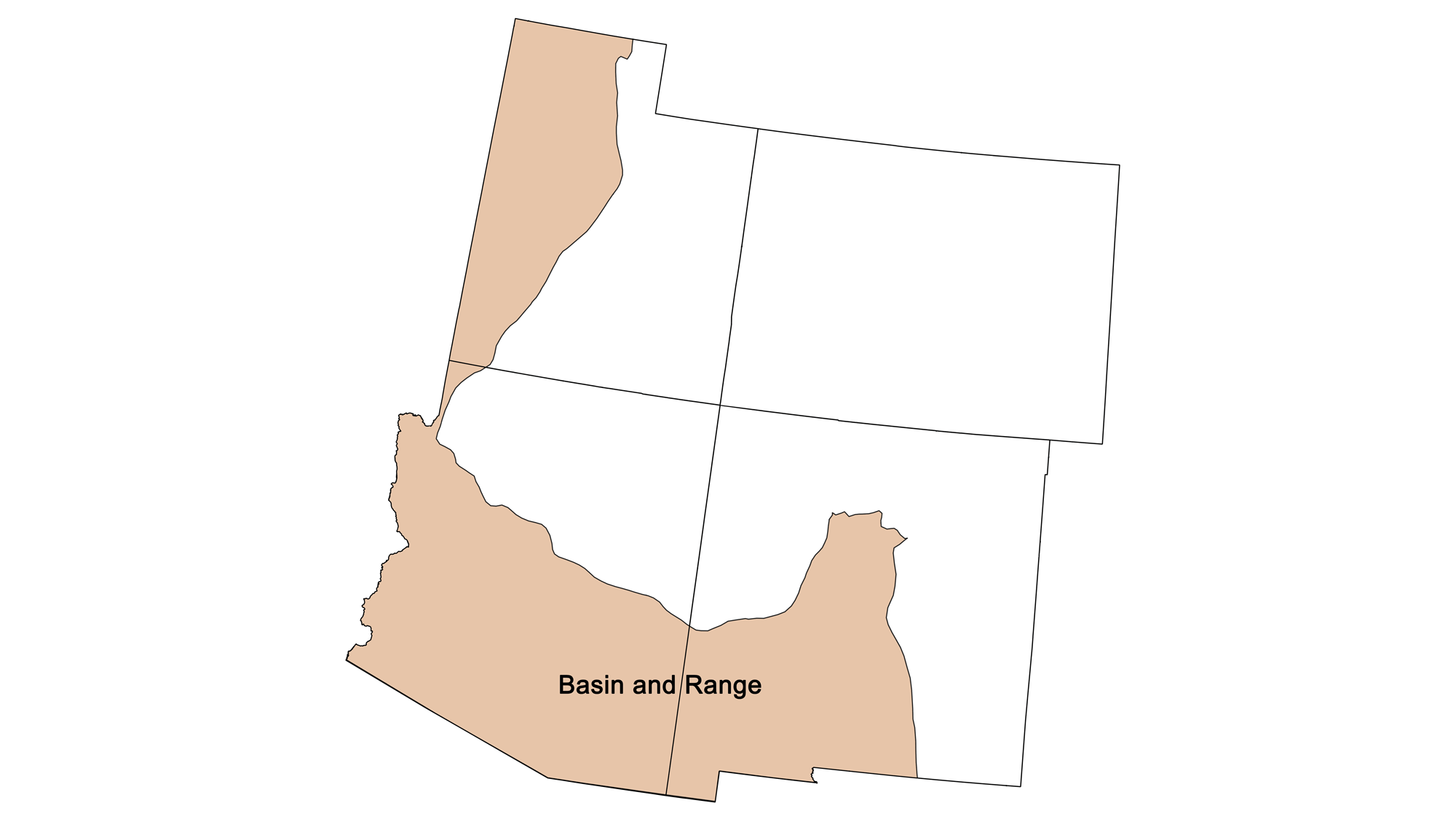

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Basin and Range region of the southwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Cambrian fossils; Ordovician fossils; Silurian fossils; Carboniferous fossils; Permian fossils; Mesozoic fossils; Cenozoic fossils; White Sands National Park; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Southwestern US" by Warren D. Allmon and Richard A. Kissel, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southwestern US, edited by Andrielle N. Swaby, Mark D. Lucas, and Robert M. Ross (published in 2016 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 26, 2022.

Image above: A trilobite (Elrathia kingi) from the Middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale, House Range, Millard County, Utah. Scale in millimeters. Photo of YPM IP 236840 by Jessica Utrup, 2021 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Paleozoic fossils

Cambrian fossils

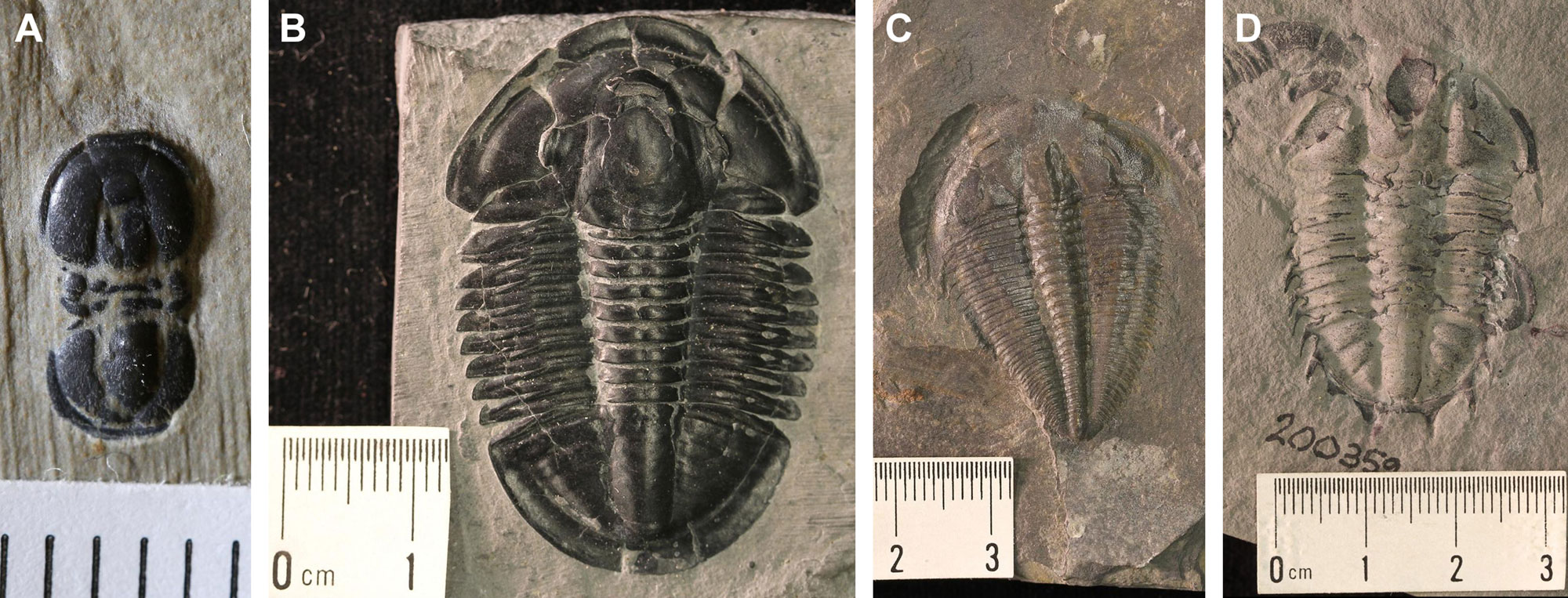

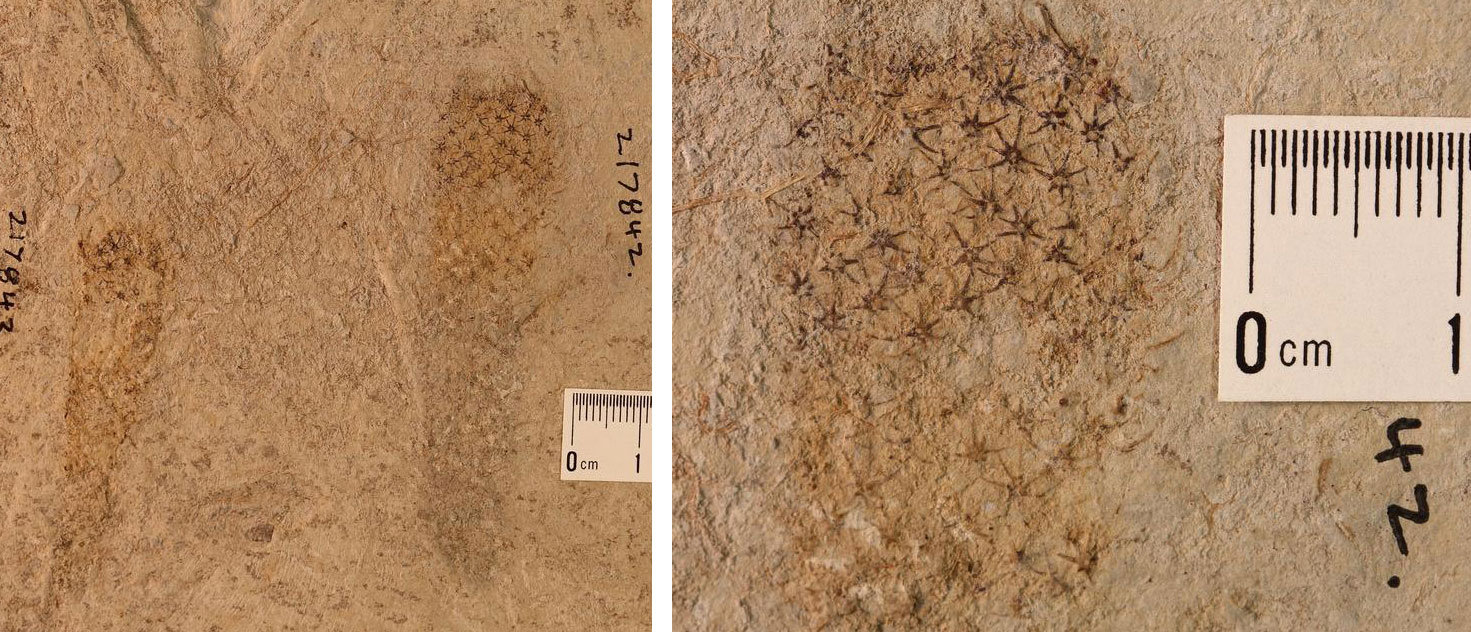

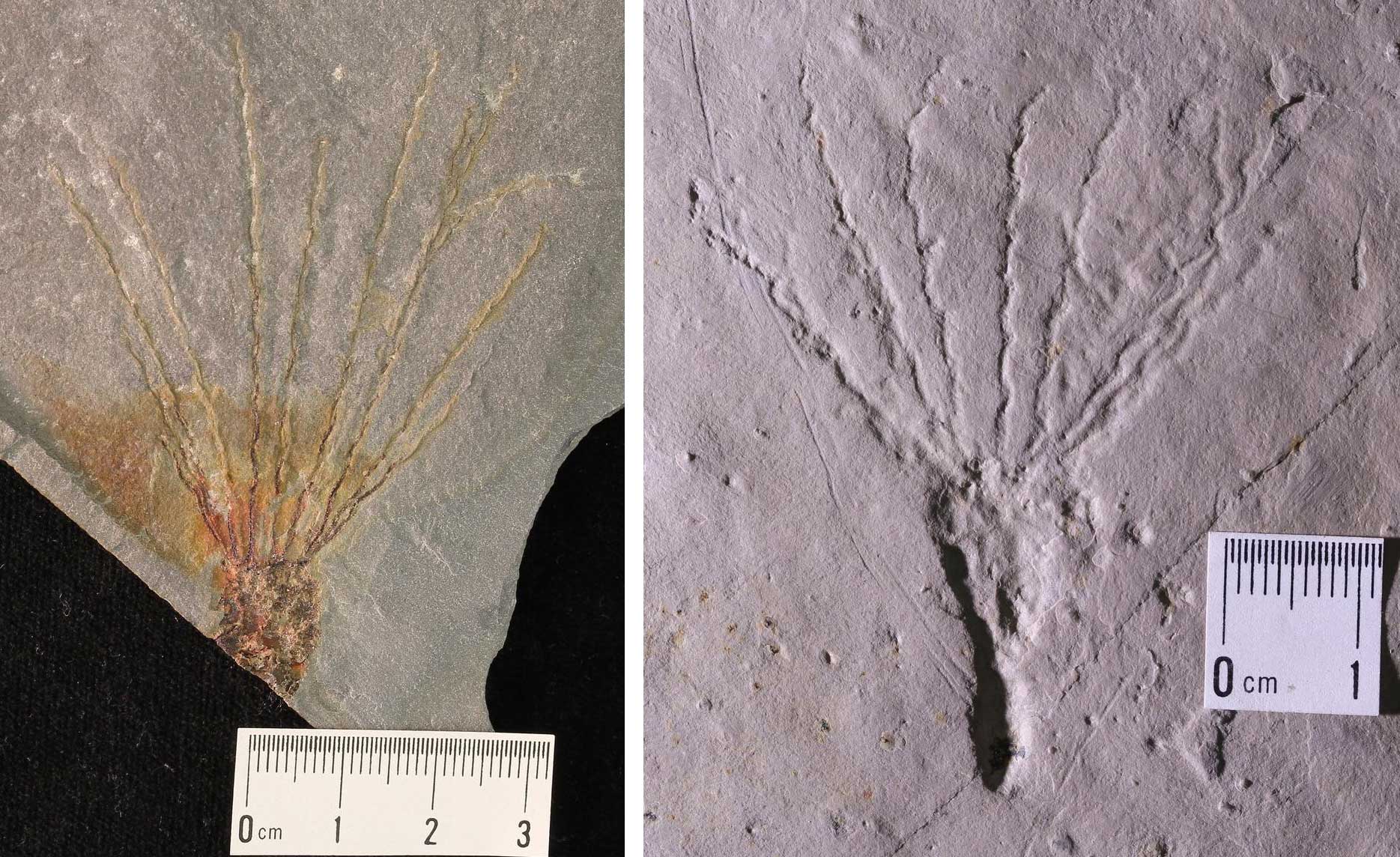

Trilobites are extremely abundant and diverse in west-central Utah, in the middle Cambrian rocks exposed in the House Range of Millard County. One of these trilobite species is especially familiar: Elrathia kingii (see the image at the top of this page) is one of the most abundant trilobite species found in North America and is commonly sold commercially. Utah’s middle Cambrian rocks (especially the Wheeler Formation) also contain fossils of sponges, brachiopods, and echinoderms, as well as soft-bodied organisms like ctenophores (comb jellies), jellyfish, worms, and arthropods similar to those of the famous Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada. Such exceptional preservation was possible in part because these rocks formed from marine sediments deposited in anoxic (very low-oxygen) conditions.

Cambrian-aged to Ordovician-aged fossils are also common in the rocks of southern Arizona (especially Cochise County) and in southwestern and south-central New Mexico. In New Mexico, the Bliss Formation contains at least 19 species of trilobites as well as numerous brachiopods and conodonts.

Trilobites from the Cambrian of Utah. Left to right: A) Agnostus interstrictus (YPM IP 325484), Middle Cambrian Wheeler Formation, Juab County. B) Asaphiscus wheeleri (YPM IP 527865), Middle Cambrian Wheeler Formation, Millard County. C) Alokistocare idahoense (YPM IP 428836), Middle Cambrian Langston Dolomite (Spence Shale), Box Elder County. D) Kootenia (YPM IP 200359), Middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale, Drum Mountains, Millard County. All photos by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Fossil sponge (Chancelloria) from the Cambrian Wheeler Shale, Millard County, Utah. Left: Two fossil sponges. Right: Detail of one of the fossil sponges in the first image, showing star-shaped spicules. Photo of specimen YPM IP 217842 by Jessica Utrup, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

An echinoderm (Gogia) from the Middle Cambrian of Utah. Left: Gogia granulosa (YPM IP 530446) from the Spence Shale, Wellsville Mountains. Right: Gogia (YPM IP 530493) from the Wheeler Shale, Millard County. Photos by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

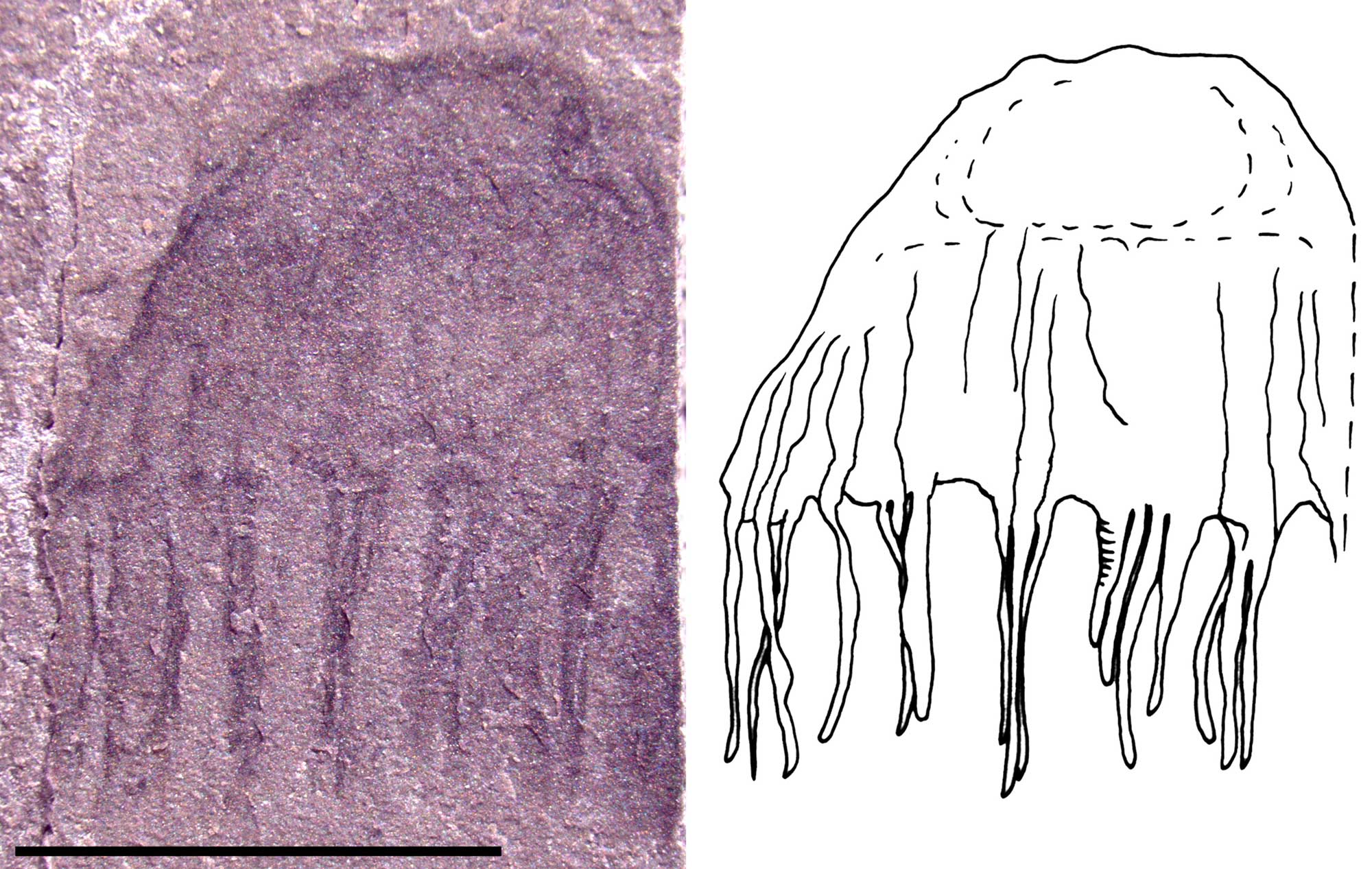

A jellyfish from the Middle Cambrian Marjum Formation, House Range, Utah. Left: Photo of specimen. Right: Drawing of the same specimen. Scale = 0.5 cm (about 0.2 inches). Source: Figure 3 from Cartwright et al. (2007) PLoS ONE 2(10): e1121 (Creative Common Attribution license, image resized).

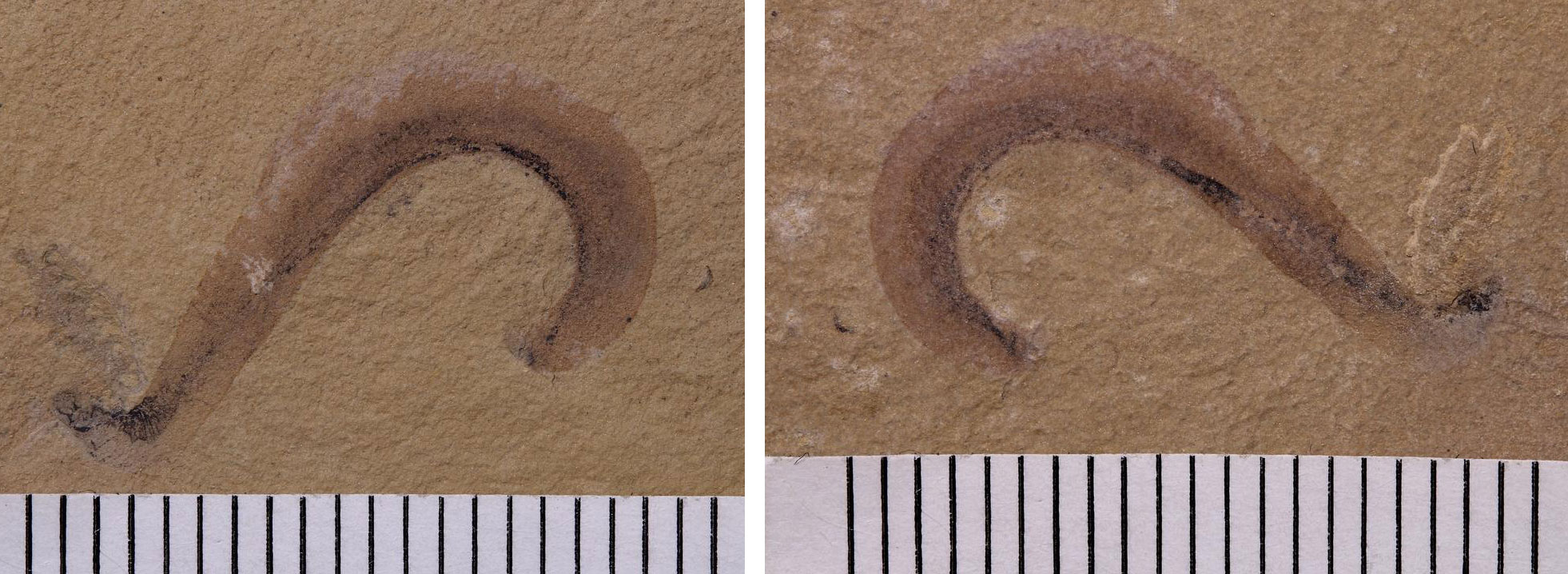

Worm (Ottoia) from the Cambrian Wheeler Shale, Millard County, Utah (part and counterpart of same specimen shown). Photo of specimen YPM IP 204289 by Jessica Utrup, 2021 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Soft-bodied arthropod (Thelixiope spinulosa) from the Middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale, House Range, Utah. Left: Part and counterpart of the same fossil specimen (one image flipped so that they are facing the same direction). Notice the long spine on the head and the body segments with spines. Right: Reconstruction of the living animal. Images from Figure 5 and Figure 8 in Lerosey-Aubril et al. (2020) PeerJ 8:e8879 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, images modified).

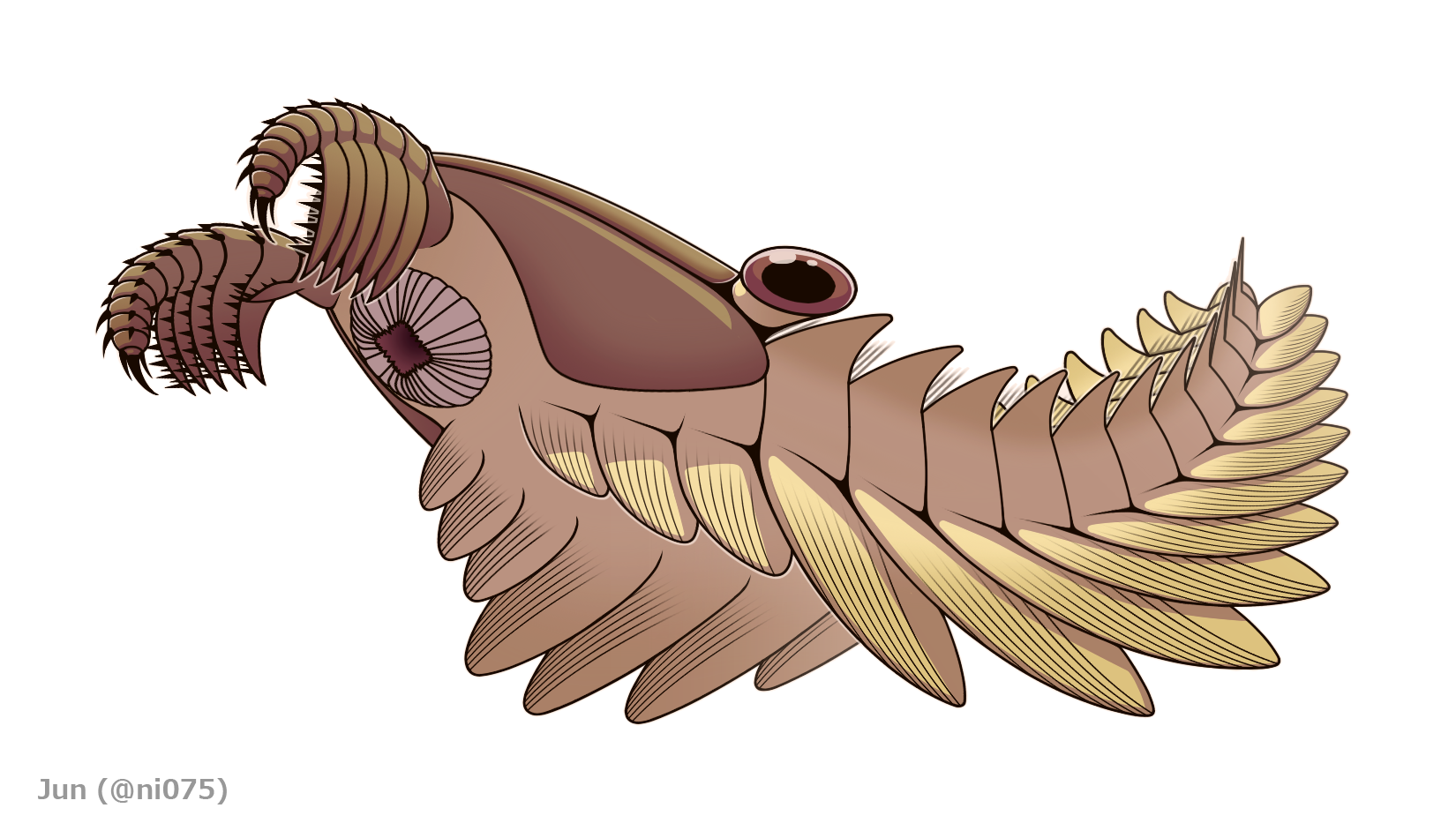

A hurdiid radiodont (Buccaspinea cooperi) from the Middle Cambrian Marjum Formation, House Range, Millard County, Utah. Source: Figure 2 in Pates et al. (2021) PeerJ 9:e10509 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Reconstruction of a hurdiid radiodont (Peytoia nathorsti), which is known from from the Middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale and the Midde Cambrian Marjum Formation of Utah. Reconstruction by Junnn11 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Ordovician fossils

The early Ordovician El Paso Formation and overlying Montoya Formation extend from southern Arizona and New Mexico into western Texas. More than 400 species of marine invertebrates have been reported from these two units, including trilobites, corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, nautiloids, gastropods, graptolites, and the oldest known crinoids in the world. Ordovician rocks also occur in scattered outcrops across west-central and northwest Utah, and contain some of the most diverse and best preserved marine assemblages of this age anywhere in the world.

A graptolite (Phyllograptus typus), Middle Ordovician, Ibex Springs, Utah. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

A crinoid (Ibexocrinus lepton) from the Ordovician Kanosh Shale, Millard County, Utah. Photo of USNM PAL 165239 by Crinoid Type Project (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

A crinoid (Pogocrinus antiquus) from the Ordovician Fillmore Limestone, Millard County, Utah. Photo of USNM PAL 249643 by Crinoid Type Image Project (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Silurian fossils

Silurian-aged rocks are much less abundant in the Basin and Range than are older or younger rocks. In Millard County, Utah, Silurian rocks contain corals and brachiopods. In southern New Mexico and central Arizona, middle and late Devonian deposits contain abundant and diverse marine fossils, especially brachiopods, corals, and bryozoans.

Carboniferous fossils

Mississippian fossils

Carboniferous rocks in the Basin and Range represent an archipelago of warm, shallow seaways and uplifted islands. The Mississippian Escabrosa Limestone in south-central Arizona is similar to the Grand Canyon’s Redwall Limestone. Although many fossils in the Escabrosa are not as well preserved as those in the Redwall, the unit still contains abundant crinoids, mollusks, bivalves, brachiopods, corals, bryozoans, and foraminifera. Mississippian marine invertebrates are also abundant in Utah.

A crinoid (Bridgerocrinus jamisoni) from the Mississippian Henderson Canyon Formation, Logan Canyon, northern Utah, near the border between the Basin and Range and Rocky Mountain physiographic provinces. Photo of USNM PAL 487224 by Crinoid Type Project (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Rugose corals or horn corals (Turbophyllum) from the Mississippian Great Blue Limestone, Cache Canyon, northern Utah, near the border between the Basin and Range and Rocky Mountain physiographic provinces. Photos of YPM IP 529539 by Jessica Utrup, 2015 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, via GBIF.org).

Pennsylvanian fossils

There is a strong Pennsylvanian fossil record in New Mexico. Fusulinids (a type of large foraminiferan that dwells on the seafloor) are the most important group for biostratigraphy in the Carboniferous and Permian rocks of the Basin and Range. More than 200 species of these creatures have been described from Pennsylvanian and Permian rocks in the Big Hatchet Mountains of Hidalgo County in southwestern New Mexico.

Other Pennsylvanian marine invertebrates found in the Basin and Range include corals, bryozoans, gastropods, bivalves, trilobites, and (as usual) brachiopods. The Pennsylvanian Naco Formation near Payson, Arizona (just south of the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau) also contains the teeth of many types of fossil sharks. Nonmarine Pennsylvanian fossils in central and southern New Mexico include freshwater fishes, plants, and insects, as well as terrestrial amphibians and reptiles.

Fusilinids (Triticites rhodesi) from the Pennsylvanian of Socorro County, New Mexico. The scale bar is 1 millimeter (0.04 inches). Photo of USNM PAL 101122 by Loren Petruny (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

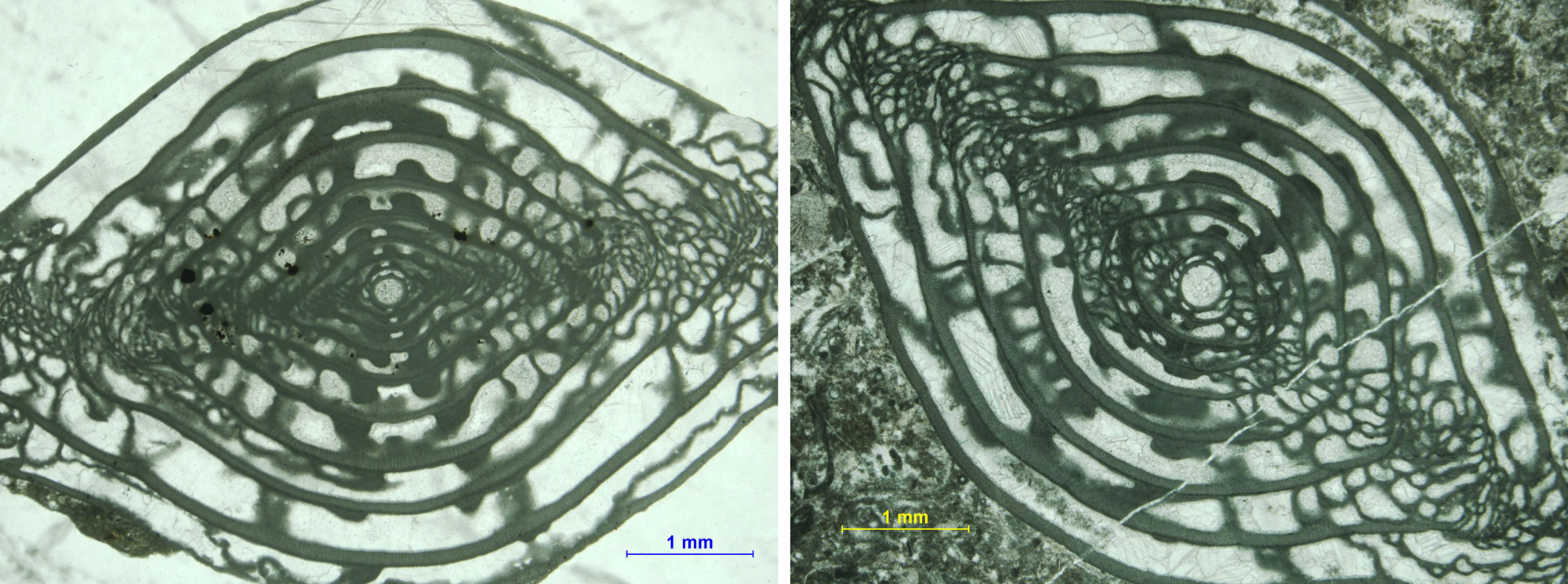

Fusilinids from the Pennsylvanian Horquilla Limstone, Hildago County, New Mexico. These fossils have been sectioned, meaning that they have been cut into thin slices so that their structure can be observed under a microscope. Left: Triticites inflatus. Right: Triticites pinguis. Photos of specimens NMMNH P-52892 and P-52943 by New Mexico Museum of Natural History Collections Digitization (via Arctos, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, images cropped and resized).

Permian fossils

As the ocean receded from the Southwest during the Permian, the Basin and Range transitioned to a mainly terrestrial environment. Marine sediments are exposed in a few places. Red beds in the Los Pinos Mountains of Socorro County, New Mexico, contain abundant fossil lungfish burrows, and Permian outcrops in western Utah contain fusulinids, conodonts, bivalves, and brachiopods.

A brachiopod (Dictyoclostus ivesi), Late Permian Concha Limestone, Whetstone Mountains, Cochise County, Arizona. From left to right: Top, underside, hinge. Photos of YPM IP 41020 by Jessica Utrup, 2011 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, via GBIF.org).

In New Mexico’s Permian rocks, the footprints of terrestrial vertebrates are widespread and abundant. Reptile and amphibian prints in the Abo and Robledo Mountain formations, for example, are the basis for the recent establishment of Prehistoric Trackways National Monument near Las Cruces in Doña Ana County. This area contains one of the most abundant assemblages of nonmarine Paleozoic trace fossils in the world, with more than 20 different kinds of traces, and it has been called an “ichnofossil Lagerstätte.” (A Lagerstätte is an exceptional fossil deposit.)

A fossil vertebrate skeleton (left, close up; right, part and counterpart specimens) discovered by Ron Fields and Emily Thorpe in 2016, Permian Arroyo de Alamillo Formation (Yeso Group), Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, New Mexico. Left photo, NPS photograph by Emily Thorpe (public domain); right photo, National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division (public domain).

Possible Dimetrodon track, Permian, Prehistoric Trackways National Monument, New Mexico. Photo by Medtrails (Wikimedia, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Mesozoic fossils

Mesozoic marine rocks are uncommon in the Basin and Range. While marine environments spread over the area multiple times during the Mesozoic, many of the corresponding rocks have been destroyed by erosion or buried by other sediments.

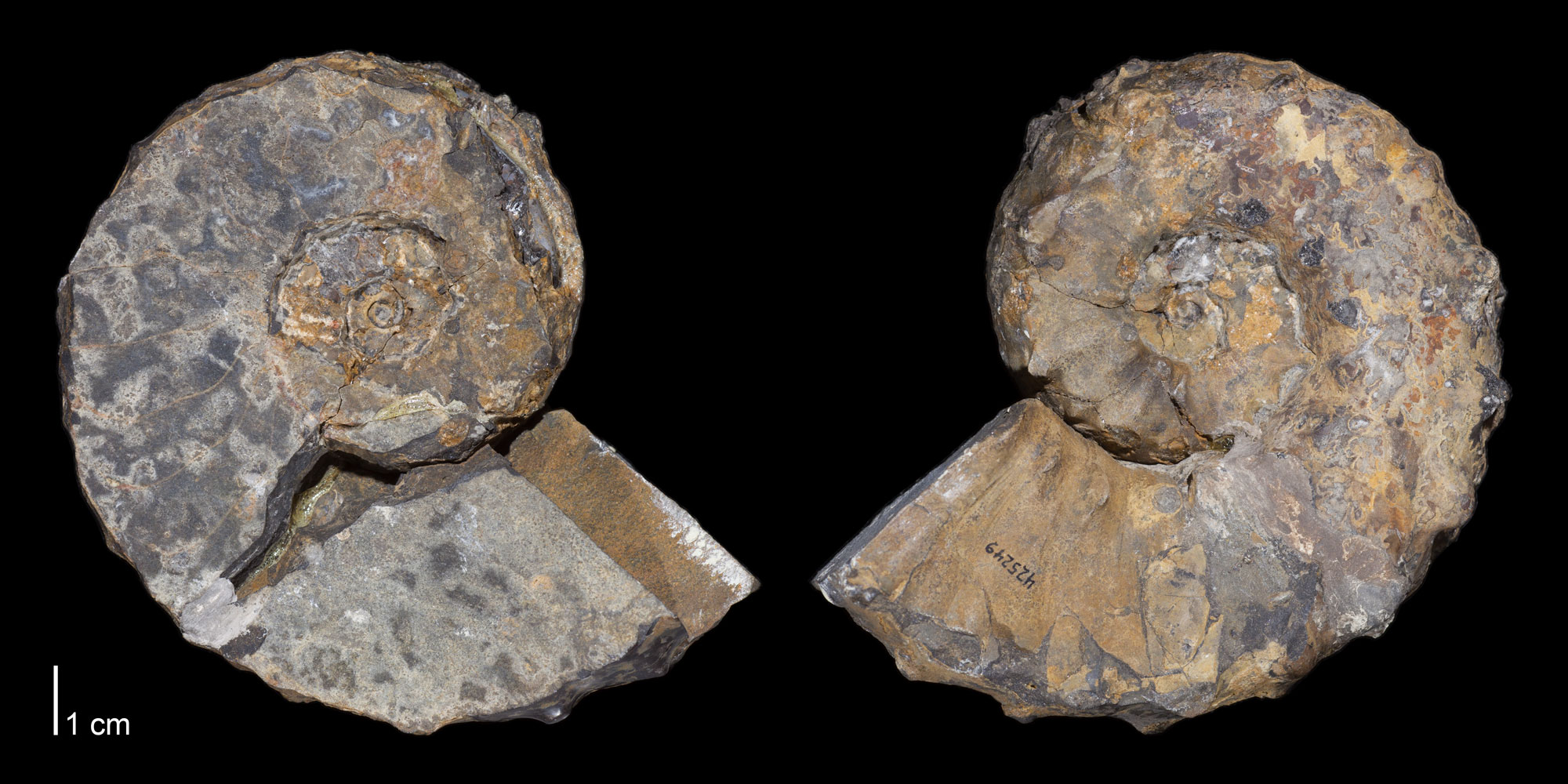

Outcrops containing marine fossils include the Triassic Moenkopi, Dinwoody, and Thaynes formations; the Jurassic Twin Creek, Carmel, and Curtis formations; and the Cretaceous Aspen-Mowry Shale and Dakota beds. Ammonoids, snails, fish scales, and bivalves are found in these rocks. Rudists (a strange type of bivalve) are uncommon but have been found at a number of Cretaceous localities in New Mexico.

Ammonoid (Arctoceras), Triassic Thaynes Limestone, Confusion Range, Millard County, Utah. Photo of YPM IP 591005 by Christina Lutz, 2016 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, via GBIF.org).

Oysters (Liostrea strigilecula), Jurassic Carmel Formation, Utah. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

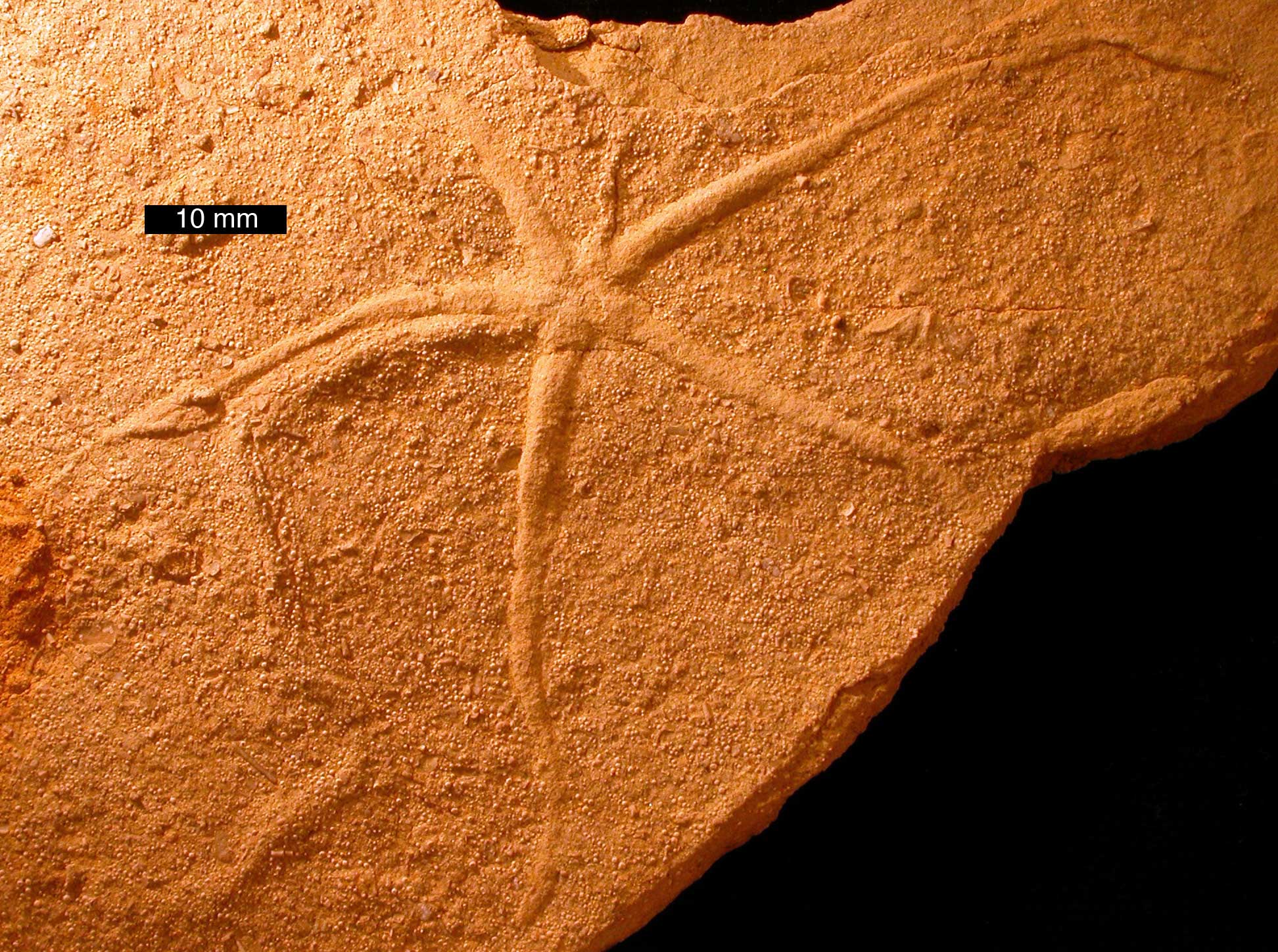

Trace fossil of an ophiuroid or brittle star (Asteriacites), Jurassic Carmel Formation, Utah. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Ammonoid (Burroceras clydense), Late Cretaceous Colorado Shale, Grant County, New Mexico. Photo of Smithsonian Natural History of Natural History specimen USNM 425249 from Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

In Washington County, in southwestern-most Utah on near the border of the Basin and Range and Colorado Plateau provinces, Early Jurassic rocks are exposed at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site. This site preserves an extraordinary diversity and abundance of trackways, as well as the skeletal remains of dinosaurs and other tetrapods, fish, and terrestrial plants.

St. George Dinosaur Discovery Center, Washington County, Utah. Photo by 5of7 (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Dinosaur footprint (Gigandipus), St. George Dinosaur Discovery Center, Early Jurassic Moenave Formation, Utah. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Cenozoic fossils

Above the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary, the rocks of southeastern and west-central Arizona and central and southern New Mexico are rich in Neogene and Quaternary land mammals. These deposits include proboscideans (relatives of elephants) such as Gomphotherium, Cuvieronius, and Stegomastodon, as well as the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) and at least two species of mammoth (Mammuthus columbi and Mammuthus meridionalis). Also present are camels (Stenomylus, Protolabis, Michenia, Megacamelus, Megatylopus, Hemiauchenia, Procamelus), rhinos (Diceratherium, Teleoceras), carnivores (Borophagus), horses (Dinohippus, Onohippidium, Nannippus, Equus giganteus, E. simplicidens, and E. occidentalis), ground sloths (Megalonyx leptostomus, Glossotherium chapadmalense), and a species of glyptodont (Glyptotherium texanum). There are rabbits and many kinds of rodents, including the earliest known species of porcupine.

Portion of the lower jaw of a fossil canid (Canis lepophagus), Pliocene, Greenell County, Arizona. Photograph of NMMNH 33184 (New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Camel (Camelops hesternus). Photo: Lower jaw, Pleistocene, Catron County, New Mexico. Inset: Reconstruction of the living animal. Photograph of NMMNH 70689 (New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized). Reconstruction by Sergiodlarosa (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, white border added).

White Sands National Park

Pleistocene fossil mammals are found at White Sands National Park of New Mexico. White Sands is a large gypsum deposit in the Tularosa Basin that includes dunes made up of gypsum sand. During the Pleistocene, gypsum eroded from mountains surrounding the Tularosa Basin and collected in an ancient lake on the basin floor called Lake Otero. At the end of the Pleistocene, Lake Otero dried up, leaving behind the gypsum that now forms dunes and the Alkali Flat (a gypsum flat) at White Sands.

Lake Otero probably attracted a variety of animals during the Pleistocene. Herbivores (plant-eaters) like Columbian mammoths, camels, and Harlan's ground sloth, and predators like dire wolves, American lions, and saber-toothed cats lived in the White Sands region. Tracks of several of these animals have been found preserved in the gypsum.

In 2021, an especially exciting discovery was announced: human footprints. The human footprints at White Sands are dated to about 23,000 to 21,000 years old and are the oldest evidence of humans inhabiting North America.

Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) tracks, Pleistocene, White Sands National Park, New Mexico. Left photo and right photo from NPS, courtesy David Bustos (public domain).

Original caption (from USGS): "Top left: USGS research geologists Kathleen Springer and Jeff Pigati collecting seeds embedded in an ancient human footprint for radiocarbon dating. Top right: Multiple human trackways from Track Horizon 1 (white arrows), Track Horizon 3 (red arrows), and Track Horizon 4 (black arrows). Bottom left, right: Closeup photographs of excavated human trackways from Track Horizon 4." Photos by Jeff Pigati and Kathleen Springer, USGS (public domain).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin in Range in southeastern Idaho): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-br/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin in Range in far western Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-br

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Western United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin and Range in California, Nevada, and Oregon): https://earthathome.org/hoe/w/fossils-br/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/