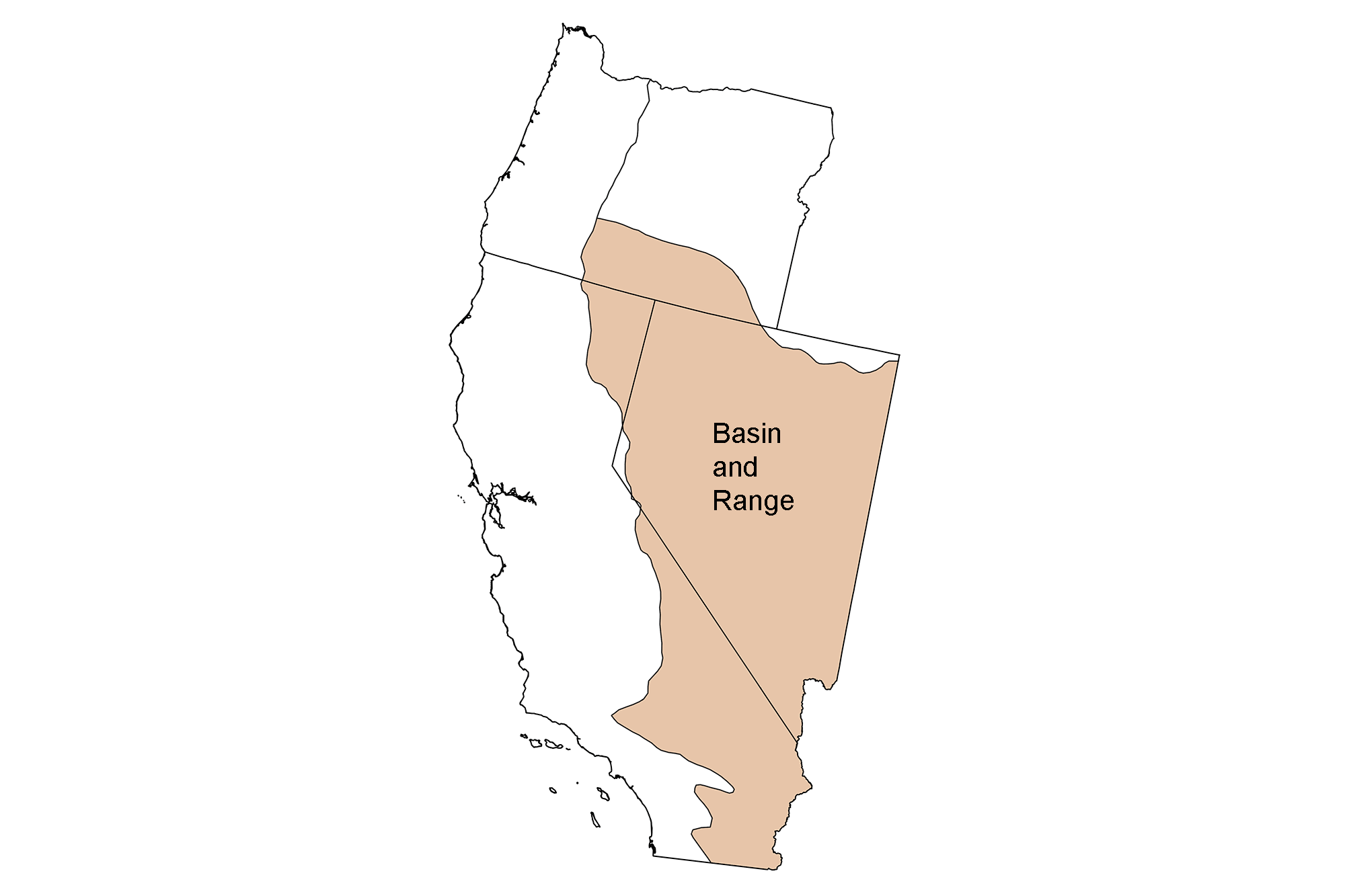

Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Basin and Range region of the western United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Mesozoic fossils; Triassic fossils; Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park; Jurassic to Cretaceous fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Paleogene fossils; Neogene fossils; Quaternary fossils; Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Western US" by Brendan M. Anderson, Alexandra Moore, Gary Lewis, and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 26, 2022.

Image above: Landscape at Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument, located a the edge of Las Vegas in Clark County, Nevada, 2015. Photo by Andrew Cattoir (National Park Service/NPS, public domain).

Paleozoic fossils

During the early Paleozoic, the area that is now the Basin and Range was a passive continental margin with no tectonic activity, similar to the East Coast of the U.S. today.

Cambrian fossils

In the Cambrian, a warm, shallow sea flooded what is now Nevada, and trilobites were abundant and diverse. Reefs were built by an extinct group of sponge-like organisms known as archaeocyathids. Exceptionally well-preserved Cambrian fossils are known from the Indian Springs Lagerstätte (Cambrian Poleta Formation) in Nevada.

Archaeocyathids (the lighter-colored, tube-like structures), Early Cambrian Wood Canyon Formation, Inyo County, California. Photo by Bob Day (University of California Museum of Paleontology/UCMP (Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, accessed via GBIF.org).

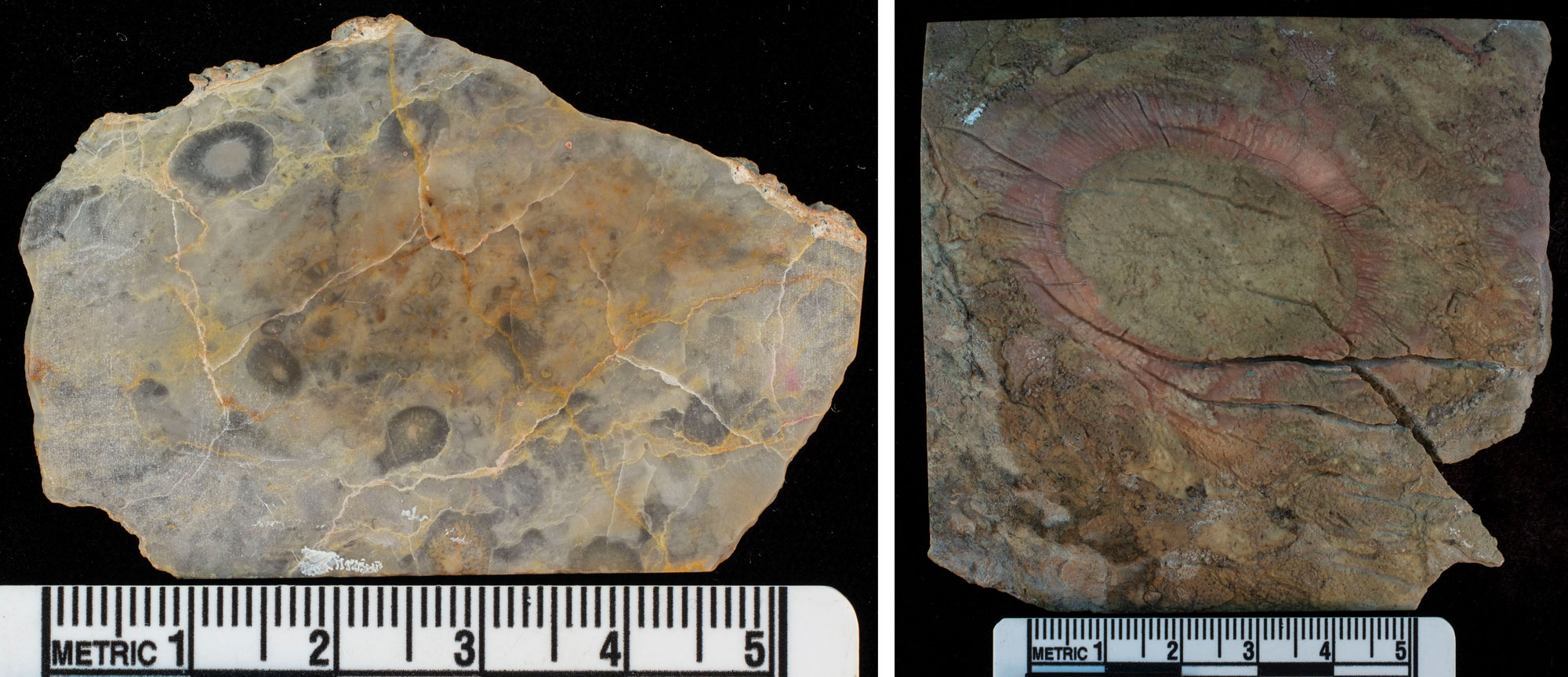

Archaeocyathids from the Cambrian of Inyo County, California. Left: Cross sections of Archaeocyathus arborensis (the gray, ring-like structures) from the Poleta Formation. Right: Cross section of an archaecyathid (the pinkish, ring-like structure) from the Harkless Formation. Photos of UCMP B-4022 and UCMP 116068 by Bob Day (University of California Museum of Paleontology/UCMP (Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, accessed via GBIF.org).

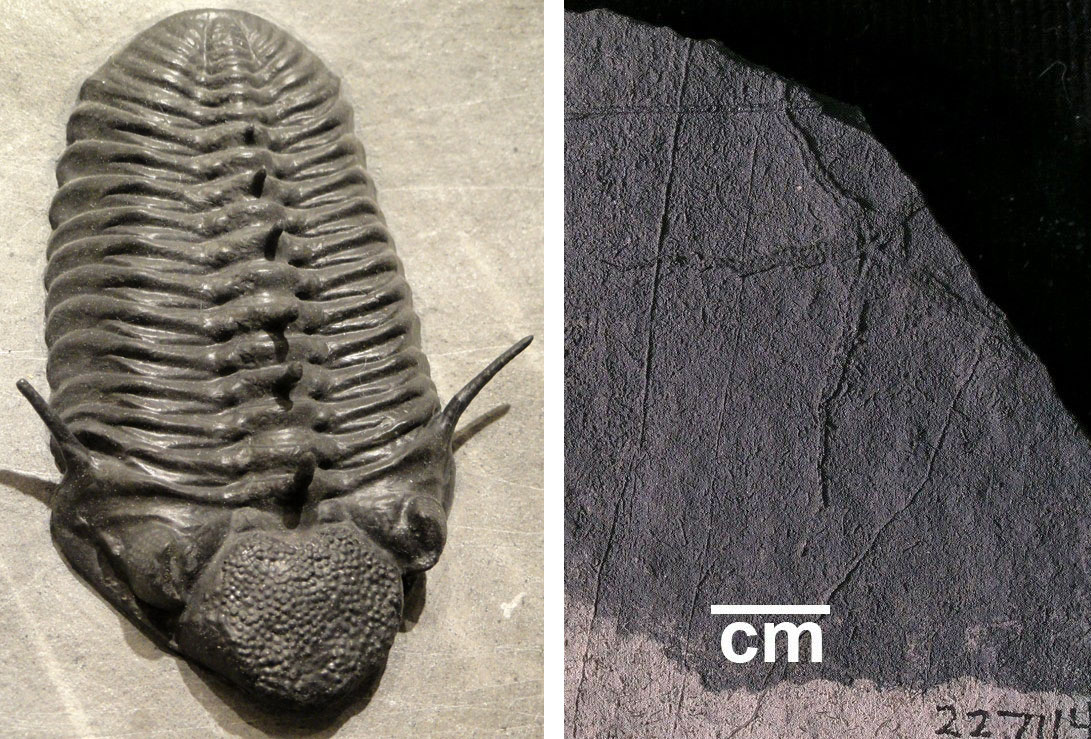

Early Cambrian trilobites from Nevada. Left: Nevadia weeksi (YPM IP 203936) from the Campito Formation, Esmeralda County. Right: Olenellus (YPM IP 163523) from the Pioche Formation, Lincoln County. Photos by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

A trilobite (Nevadia parvoconica), Indian Springs Lagerstätte, Early Cambrian Poleta Formation, Esmeralda County, Nevada. Photo by Paleontological Research Institution (PRI) on GBIF.org (CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

An early echinoderm (Helicoplacus curtisi), Early Cambrian Poleta Formation, California. Photo by Bruce Martin (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Devonian fossils

Devonian outcrops occur in central Nevada. These preserving marine invertebrates as well as vertebrates, like the fish Tinirau clackae. Tinirau clackae is from a group of fishes closely related to tetrapods, four-legged, land-dwelling vertebrates.

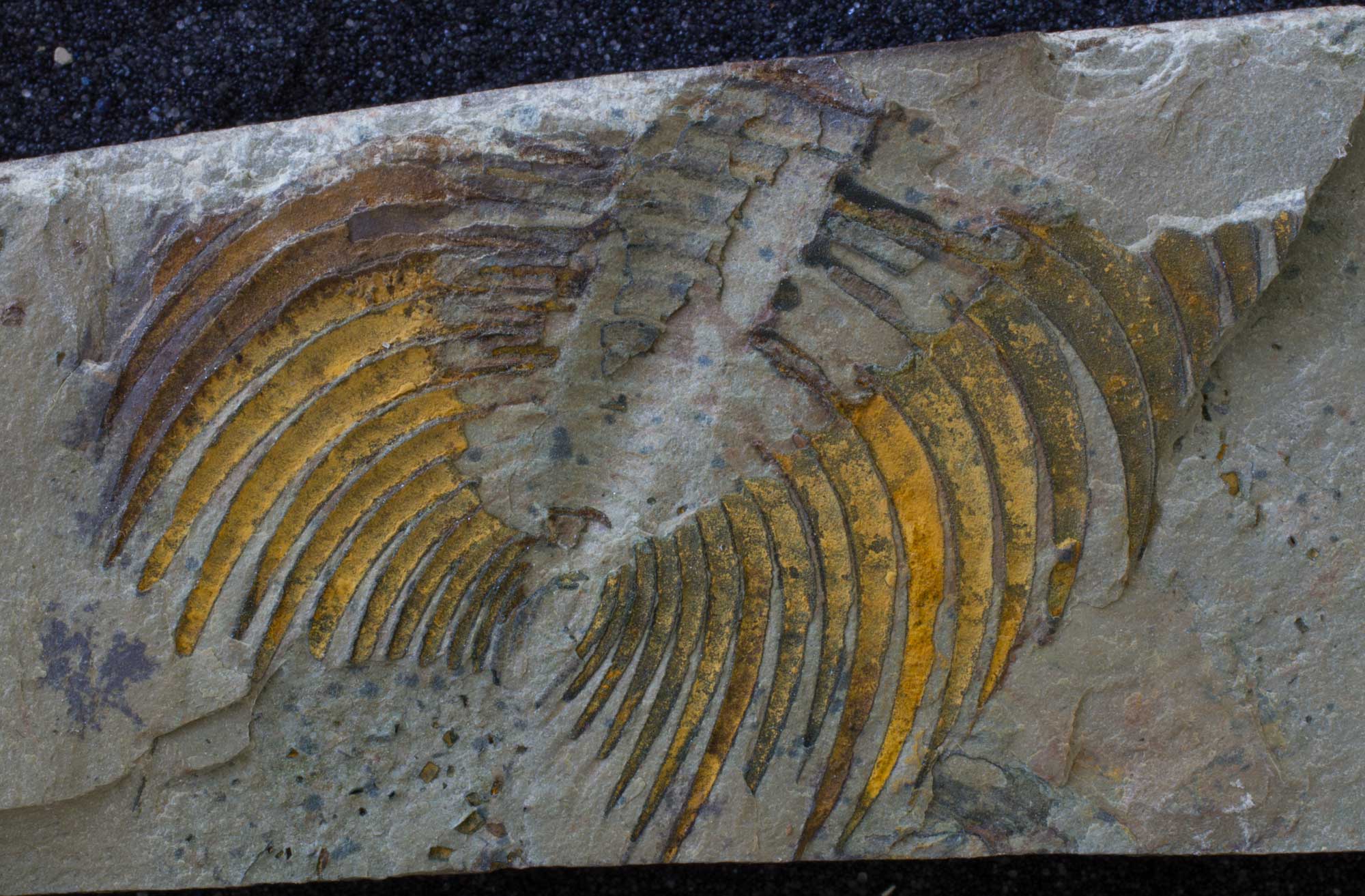

Devonian marine invertebrate fossils from Nevada. Left: A trilobite, Paciphacops claviger, Early Devonian Wenban Limestone, Cortez Range. Photo by Daderot (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication). Left: An early starfish (Protasteridae), Late Devonian Devil's Gate Formation, Eureka County. Photo of YPM IP 227114 by Susan H. Butts (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

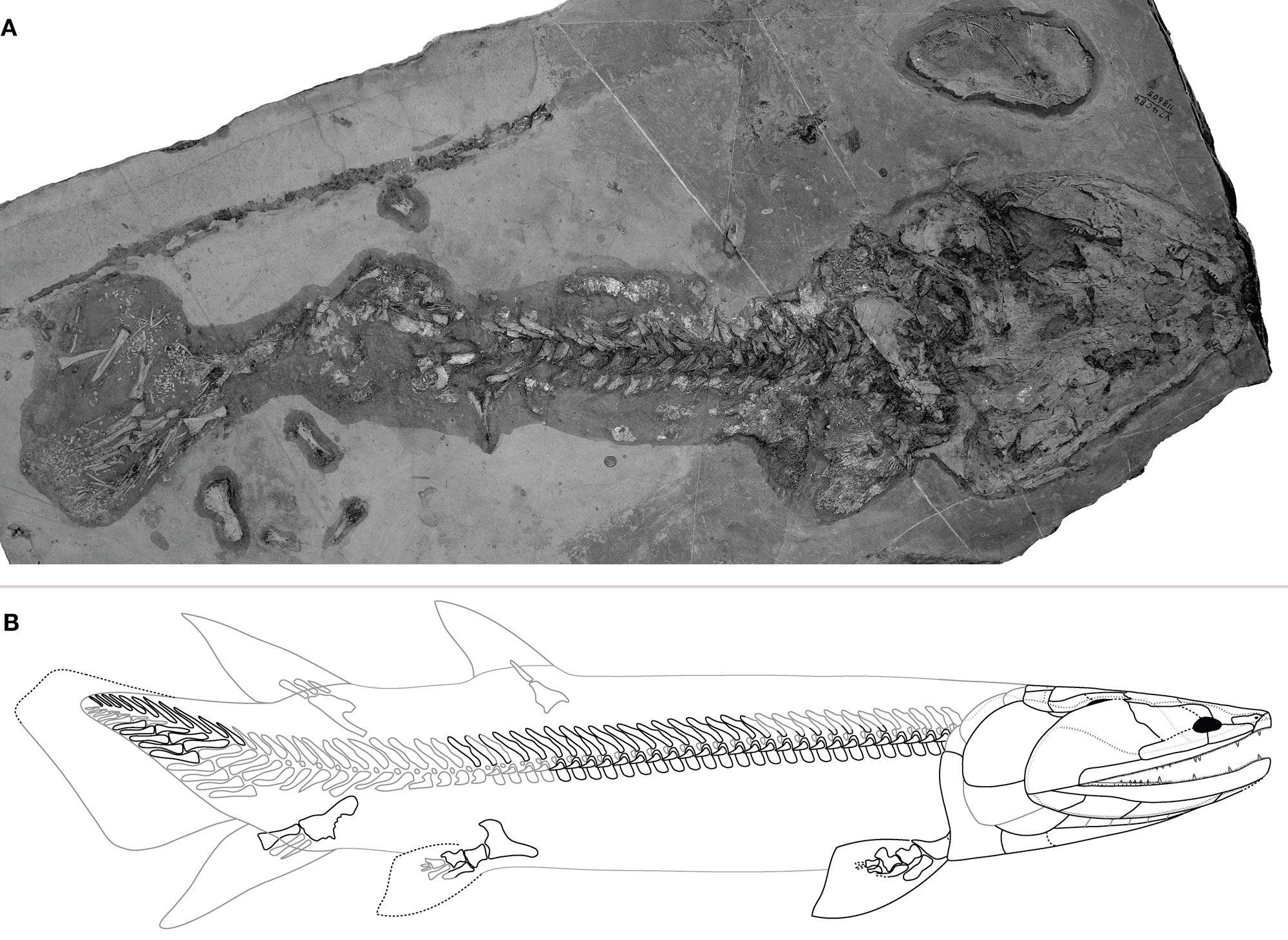

A fish (Tinirau clackae) related to tetrapods (land vertebrates) from the Devonian Red Hill beds, Eureka County, Nevada. Top (A): Photograph of the specimen, with the head towards the right and the tail towards the left. Bottom (B): Reconstruction of the animal showing features of the skeleton. Bones that were actually found are outlined in black, bones that are inferred are gray. Source: Images from Figure 2 in Swartz (2012) PLoS ONE 7(3) e33683 (Creative Commons Attribution License, image cropped, reconfigured, and resized).

Carboniferous and Permian fossils

After the Cambrian, archaeocyathids were replaced by reefs built by rugose and tabulate corals. Sponges, brachiopods, bryozoans (colonial filter-feeding animals that build calcium carbonate skeletons), and echinoderms were also part of the fauna. In deeper waters, planktonic graptolites (graptolites that live in the water column) were common.

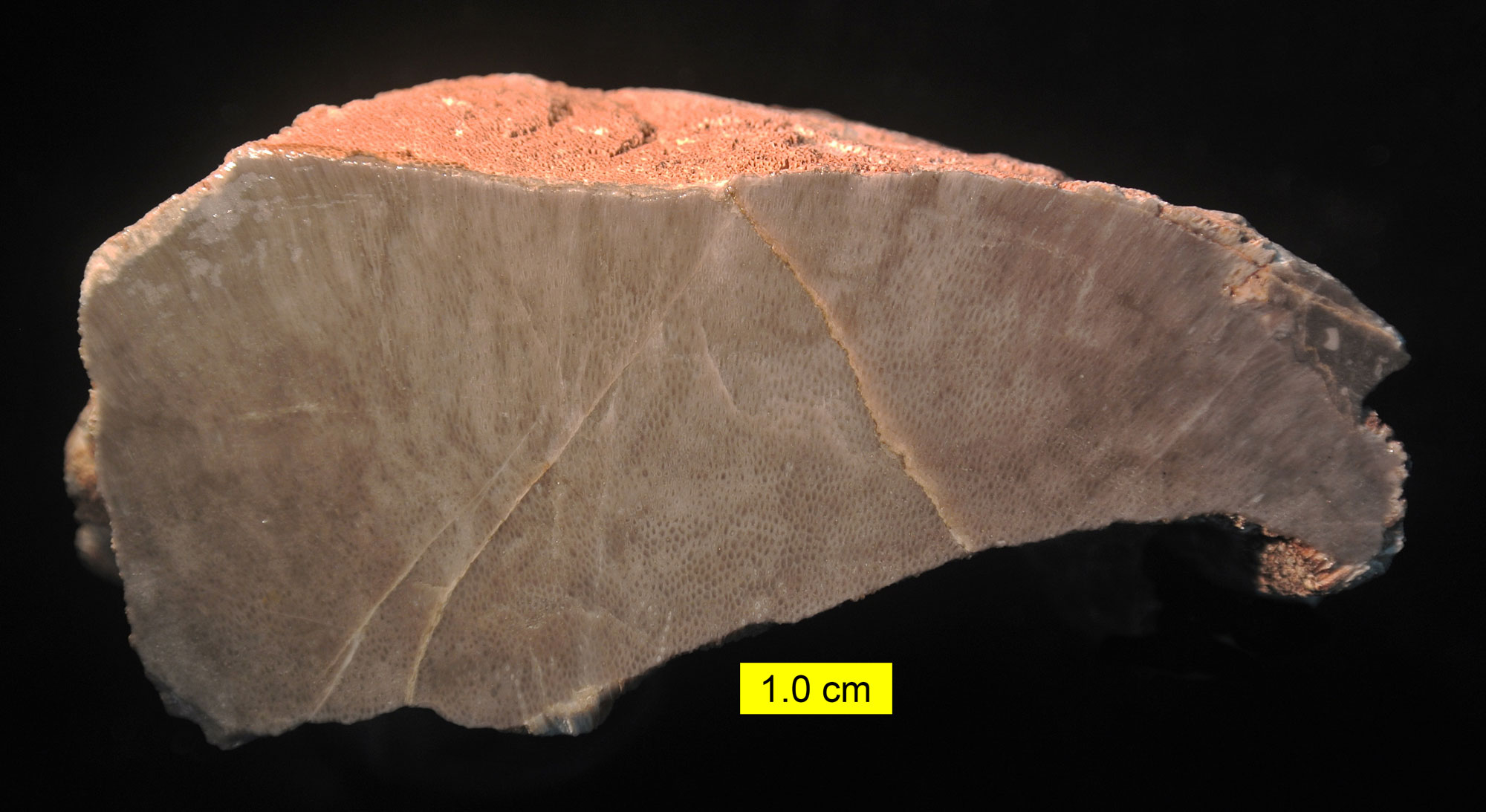

A chaetetid (enigmatic organisms now considered to be sponges) cut to show its internal structure. Carboniferous Bird Spring Formation, Spring Mountains, Nevada. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

Brachiopods from the Pennsylvanian Bird Spring Formation, Clark County, Nevada. Left: Orbiculoidea (YPM IP 406929). Center: Linoproductus (YPM IP 406931). Right: Spiriferida (YPM IP 406905). All photos by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Brachiopods from the Permian of Clark County, Nevada. Left: Spirifer rockymontanus (YPM IP 235602). Right: Productus inflatus (YPM IP 235604). All photos by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Spines of an ancient sea urchin (Archaeocidaris) from the Carboniferous Bird Spring Formation, Spring Mountains, Nevada. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

Mesozoic fossils

Triassic fossils

The Triassic and Jurassic rocks of Oregon testify to major global changes in marine life, especially when compared to the Paleozoic. The once-abundant brachiopods on the seafloor are gone, replaced by faunas composed primarily of burrowing bivalves and gastropods. Tabulate and rugose corals were replaced by scleractinian corals, which were building reefs in this region by the mid-Triassic.

Ammonoid cephalopods also diversified during the Triassic, and their fossils can be found in Oregon, California, and Nevada. Swimming with (and probably feeding on) these ammonoids were marine reptiles called ichthyosaurs.

Triassic ammonoids from Nevada. Left: Arctoceras tuberculatum (YPM IP 516918) from the Early Triassic of Elko County. Right: Nevadites hyatti (YPM IP 009355) from the Middle Triassic of the Humboldt Range. Photos by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Middle Triassic ammonoids (Tropigastrites lahontanus) from Pershing County, Nevada (5 shells, one side of each shell shown on the left, the other side of each shell shown on the right). Photos of YPM IP 009436 by Jessica Utrup, 2019 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, accessed via GBIF.org).

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park is located in a lonely stretch of Nye County, Nevada. The ichthyosaur Shonisaurus popularis was first discovered in the region in the 1920s. Shonisaurus lived around 217 million years ago, while Nevada was still covered by the ocean. In contrast to Jurassic and Cretaceous ichthyosaurs, Shonisaurus (along with other early ichthyosaurs) is thought to have lacked dorsal fins. Shonisaurus was over 15 meters (50 feet) long and was the largest known ichthyosaur until 2004, when an even larger species was discovered in British Columbia.

At the state park, a shelter was build around a group of Shonisaurus skeletons which were exposed but left in place, where they can be viewed by visitors. Shonisaurus popularis is Nevada's state fossil.

The large ichthyosaur Shonisaurus popularis from the Triassic of Nevada. Specimen on display in the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas, Nevada. Photo by Kenneth Carpenter (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Artistic interpretation of Shonisaurus popularis at Berlin-Icthyosaur State Park in Nevada. Photo Famartin (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Jurassic to Cretaceous fossils

Jurassic to Cretaceous marine fossils

Nevada’s shallow seas persisted into the Jurassic and part of the Cretaceous, and remained inhabited by ammonoids and bivalve mollusks. In the northernmost part of the Basin and Range (northern California and southern Oregon), bivalves called rudists frequently formed reef-like mounds. Rudists became extinct with the dinosaurs and many other species at the end of the Cretaceous. The sea retreated during the Late Cretaceous, and the Basin and Range became entirely terrestrial.

Jurassic to Cretaceous dinosaurs

Jurassic dinosaur tracks are known from the Aztec Sandstone in southern Nevada. Tracks have been found, for example, at Valley of Fire State Park, located at the northeastern end of Lake Mead, and in Springs Preserve, near Las Vegas.

Cretaceous dinosaur bones have been discovered in central and southern Nevada. In 2021, scientists announced a new Cretaceous dinosaur, Nevadadromeus schmidti. This dinosaur was found in Valley of Fire State Park and is the first dinosaur known exclusively from Nevada.

Cenozoic fossils

Paleogene fossils

During the Paleogene, the region was home to mammals. Petrified wood is also found.

Jaw of a fossil hoofed mammal (Fouchia elyensis, family Hyrachyidae), an extinct relative of modern rhinoceroses, Eocene Sheep Pass Formation, White Pine County, Nevada. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Petrified juniper wood (Juniperus) from the Oligocene of Elko County, Nevada. Photo by Kevmin (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Neogene fossils

During the Neogene, the region was home to diverse and abundant mammals such as camels, mammoths, and rhinoceroses. Freshwater lakes dotted the area and were inhabited by fish such as sticklebacks, Nevada killifish, and topminnows. In Death Valley National Park, California, Pliocene-aged fossil mammal and bird tracks have been found in the Copper Canyon Formation.

A fossil frog (Miopelodytes gimorei), Miocene Elko Shale, Elko County, Nevada. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

A fossil killifish (Parafundulus nevadensis), Miocene to Pliocene Lahontan Formation, Nevada. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

A fossil stickleback (Gaterosteus williamsoni), Miocene to Pliocene Lahontan Formation, Churchill County, Nevada. Photo by Michael Brett-Surman (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, public domain).

Camel tracks, likely Pliocene, Death Valley National Park, California. Photo by National Park Service/NPS (public domain).

Quaternary fossils

During the last glacial period (Pleistocene), southern Oregon was home to many species of large and now-extinct mammals, including Arctodus, the giant short-faced bear, which was 1.8 meters (6 feet) tall at the shoulder with 25- centimeter-long (10-inch-long) paws. Alongside these massive mammals lived Teratornis, a giant vulture with a wingspan of up to 3.8 meters (12.5 feet); the modern California condor, the largest living bird in North America, has only a 2.7-meter (9-foot) wingspan.

Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument

Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument and Ice Age Fossils State Park are located in Tule Springs just outside of Las Vegas in Clark County, Nevada. The site was first discovered in 1933, and large excavations were carried out in 1962 to 1963 and 2004. The 1962 to 1963 project was called the "Big Dig," a project in which giant trenches were dug in order to investigate whether humans lived at Tule Springs at the same time as the Pleistocene animals found at the site. They did not. Nevertheless, the Big Dig marks an important milestone in science, because it was the first major North American paleontological investigation to use radiocarbon (carbon-14) dating to determine the ages of fossils. The site was designated as a national monument in 2014 to preserve the significant deposit of Pleistocene fossils in the area.

National Parks in the History of Science: Radiocarbon Dating. A video about radiocarbon dating and its use in the 1960s to investigate Tule Springs. Video by National Park Service.

Trench from the "Big Dig" in the 1960s, photographed in 2014. Photo by Alan O'Neill (National Parks Conservation Association on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Animals found at Tule Springs range from about 100,000 to 12,500 years old. They include classic Pleistocene megafauna (large animals) like extinct bison, camels (Camelops hesternus), horses, ground sloths, Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi), pronghorn antelope, North American lions (Panthera atrox), saber-toothed cats (Smilodon fatalis), and dire wolves (Canus dirus). Additionally, birds (including Teratornis merriami), small vertebrates like reptiles, and invertebrates like snails and clams have also been found.

Fossil horse tooth found by a paleontologist at Tule Springs, 2010. Photo by San Bernardino County Museum (National Parks Conservation Association on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Mammoth tusk being excavated from sediments at Tule Springs by the San Bernandino Museum, California, 2010. Photo by Alan O'Neill (National Parks Conservation Association on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin in Range in southeastern Idaho): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-br/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin in Range in far western Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-br

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin and Range in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/fossils-br

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/