Page snapshot: Introduction to energy of Columbia Plateau and Rocky Mountains regions of the western United States, including fossil fuels and renewable energy.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Fossil fuels; Geothermal energy; Hydroelectricity; Wind energy; Resources.

Credits: Some of the text of this page comes from "Energy in the western US" by Carlyn S. Buckler and Gary Lewis, chapter 7 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Western US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions and additions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated September 8, 2022.

Image above: McNary Dam on the Columbia River on the Oregon-Washington border. The ramp-like structure on the left side of the dam is a fish ladder that allows adult salmon and steelhead to navigate over the dam as they move upstream. Photo by Bonneville Power on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Overview

The active tectonics that resulted in the Columbia Plateau flood basalts and the growth of the Rocky Mountains to the east have created a region rich in hydroelectric and wind energy, as well as the potential for geothermal energy. The Pacific Northwest is well known for its extensive network of dams, many of which provide power to the region.

Ice Harbor Dam on the Snake River, eastern Washington. Photo by Bonneville Power on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Fossil fuels

Fossil fuel development is not significant in the region. The Columbia Plateau has seen very little fossil fuel development because it is covered by thick volcanic deposits that make exploration and recovery challenging. The volcanic rocks overlie Cenozoic lake deposits and older marine rocks that may contain oil and gas resources, but they have not been considered economically viable to develop.

Basalt cliffs exposed at Dry Falls Lake, Washington. Photo by Chris Light (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Geothermal energy

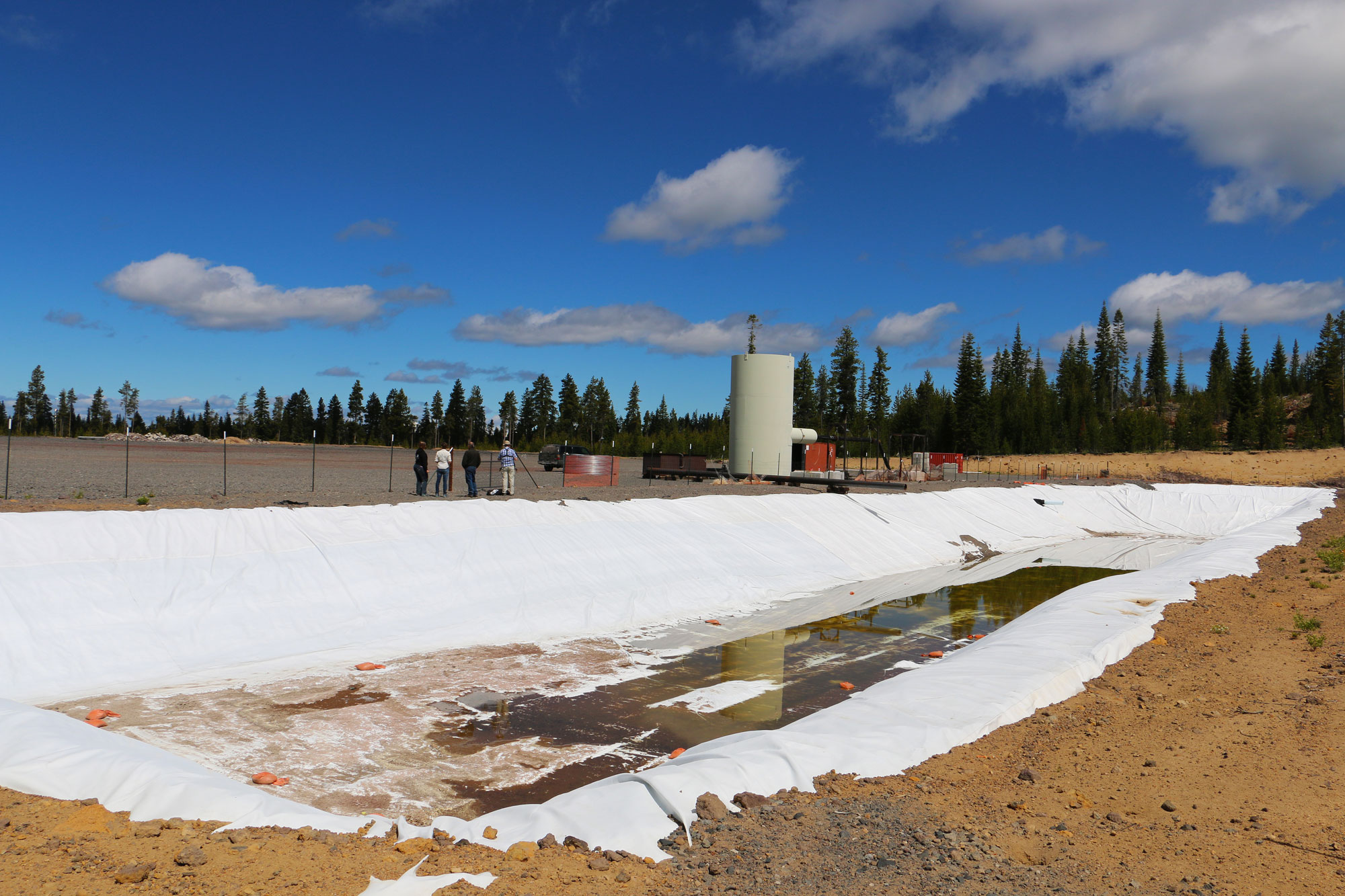

The NEWGEN Site (Newberry Geothermal Energy) is located on Newberry Volcano in central Oregon. This site is not a commercial geothermal plant, but is rather an experimental field site meant to explore the potential for geothermal energy in the region. More comprehensive development of geothermal energy may be an area of growth on the Columbia Plateau in the future.

Newberry Geothermal Lease Project, Deschutes National Forest, Oregon, 2014. Photo by Michael Campbell, BLM (Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Hydroelectricity

Columbia Plateau

Nestled between the Cascade and Rocky Mountain ranges, the Columbia Plateau was an inland sea for tens of millions of years, until about 15 million years ago when volcanic activity deposited layer upon layer of lava. Because of its topography, this region is tops in the nation for hydroelectric power generation.

The Grand Coulee Dam is the largest hydroelectric plant in the U.S. The Grand Coulee was built from 1933 to 1942 and was originally designed to irrigate the Northwest. However,World War II significantly increased the need for energy in the region, because the Northwest became a manufacturing hub for the war. A third power station was added to the complex in 1974, making it the largest, most productive hydroelectric plant in the nation.

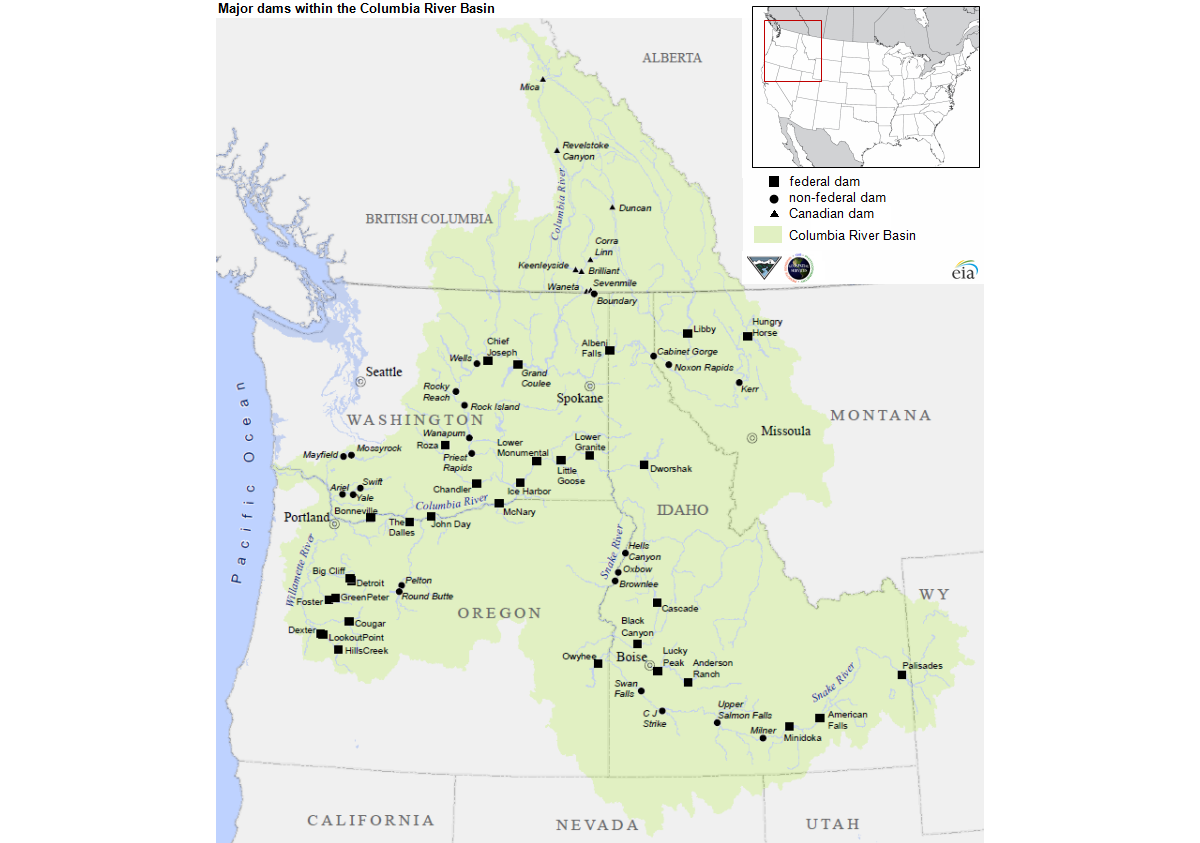

Major dams of the Columbia River Basin. Source: U.S. Energy Information, from Bonneville Power Administration.

Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River, Washington. This hydroelectric plant has a capacity of more than 6800 MW. Photo by Bureau of Reclamation (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

Rocky Mountains

The Boundary Dam on the Pend Oreille River in northeastern Washington was constructed in 1967. The hydroelectric plant associated with the dam is operated by City Light and has a capacity of 1100 MW. It supplies the city of Seattle, Washington, with a large amount of its power.

Boundary Dam under construction on the Pend Oreille River, Washington, 1966. Source: Item 188283, City Light Photographic Negatives, Record Series 1204-01 (Seattle Municipal Archives on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

Boundary Dam and Boundary Reservoir on the Pend Oreille River, Washington. Photo taken on September 5, 1967. Source: Item 190031, City Light Photographic Negatives, Record Series 1204-01 (Seattle Municipal Archives on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped).

PeeWee Falls on Boundary Reservoir, Pend Oreille River, Washington, 2016. Photo by Jeff Clark, BLM (Bureau of Land Management Oregon & Washington on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Salmon, steelhead, and dams

While dams and hydroelectric plants are sources of abundant clean energy, they also have some negative environmental impacts. Dams in the Columbia River Basin and other river systems in the Pacific Northwest have significantly altered the ecology of the region, particularly affecting salmon and steelhead. The salmon and steelhead in this region are anadromous, meaning that they live in the ocean but spawn in freshwater. These fish swim many miles upstream from the ocean to spawn, and dams are barriers that can prevent them from reaching their spawning grounds. Furthermore, turbines can injure or kill young fish swimming downstream to the ocean. The building of dams in the Pacific Northwest has greatly reduced the anadromous fish population. The reduction in salmon and steelhead has had negative impacts on the environment, on Indigenous Peoples of the Northwest who depend on the salmon and steelhead runs, and on commercial fisheries in the region.

The problems caused by dams have been partially addressed, although the solutions have proven inadequate to replenish fish populations to the levels they reached before dam building. Fish ladders, structures that allow adult salmon to maneuver around dams to travel upstream to spawning grounds, have been built on some dams. Fish hatcheries are managed by U.S. government agencies and Native American nations in an attempt to augment salmon populations. Dams have also been removed or are under consideration for removal in certain areas, which may help salmon and steelhead populations to recover. In the Columbia River Basin, advocates have called for removal of four dams on the Snake River in southeastern Washington to in help the salmon and steelhead populations to rebound.

Map of the Columbia River Basin (light green) showing major dams, species of anadromous fish inhabiting the rivers, and their conservation status. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Northwestern Division Website.

A member of the Yakima Nation using a dip net to fish for Chinook salmon on the Klickitat River, Washington, 2014. Photo by USFWS-Pacific Region (on flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

John Day Dam and fish ladder on the Columbia River, Oregon-Washington border. Construction of this dam was finished in 1971, and it can generate 2160 MW of power. The fish ladder (the structure in the foreground) is about 329 meters (1080 feet) long. Photo by Karim Delgado, U.S. Army (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Portland District, VIRIN 160927-A-VN916-1002).

Summer Chinook salmon at Entiat National Fish Hatchery, Entiat, Washington (technically located in the eastern Cascades region). The hatchery releases young summer Chinook salmon to support commercial and sport fishing and harvesting by regional tribes because natural fish populations have fallen due to the presence of the Grand Coulee Dam. Photo by USFWS Fish and Aquatic Conservation on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Wind energy

Wind energy production is second only to hydroelectric on the Columbia Plateau. Many of the wind turbines in the region are located near the Columbia River in north-central Oregon and near the Snake River in southeastern Washington.

Shepherds Flat Wind Farm, Oregon, 2011. Photo by Steven Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Wind turbines near Walla Walla, Washington, 2010. Photo by Jeffrey G. Katz (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central U.S.: Energy in the Columbia Plateau and Basin and Range (covers energy in the Columbia Plateau and Basin and Range regions of Idaho): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/energy-cp-br/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central U.S.: Energy in the Rocky Mountains (covers energy in the Rocky Mountain region of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/energy-rm/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern U.S.: Energy in the Rocky Mountains (covers energy in the Rocky Mountains region of Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/energy-rm

Earth@Home: Introduction to Energy: https://earthathome.org/hoe/energy