Spotlight: Overview of the rocks of the Basin and Range region of the western United States, including Nevada, California, and Oregon.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Precambrian; Paleozoic and Mesozoic; Cenozoic; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Rocks of the Western US" by Wendy E. Van Norden, Alexandra Moore, and Gary Lewis, chapter 2 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Western US (published in 2014 by The Paleontological Research Institution and edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle Swaby). The book was adapted for Earth@Home web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated April 21, 2022.

Image above: Tufa Towers at Mono Lake, California. Photograph by Eric Wienke (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

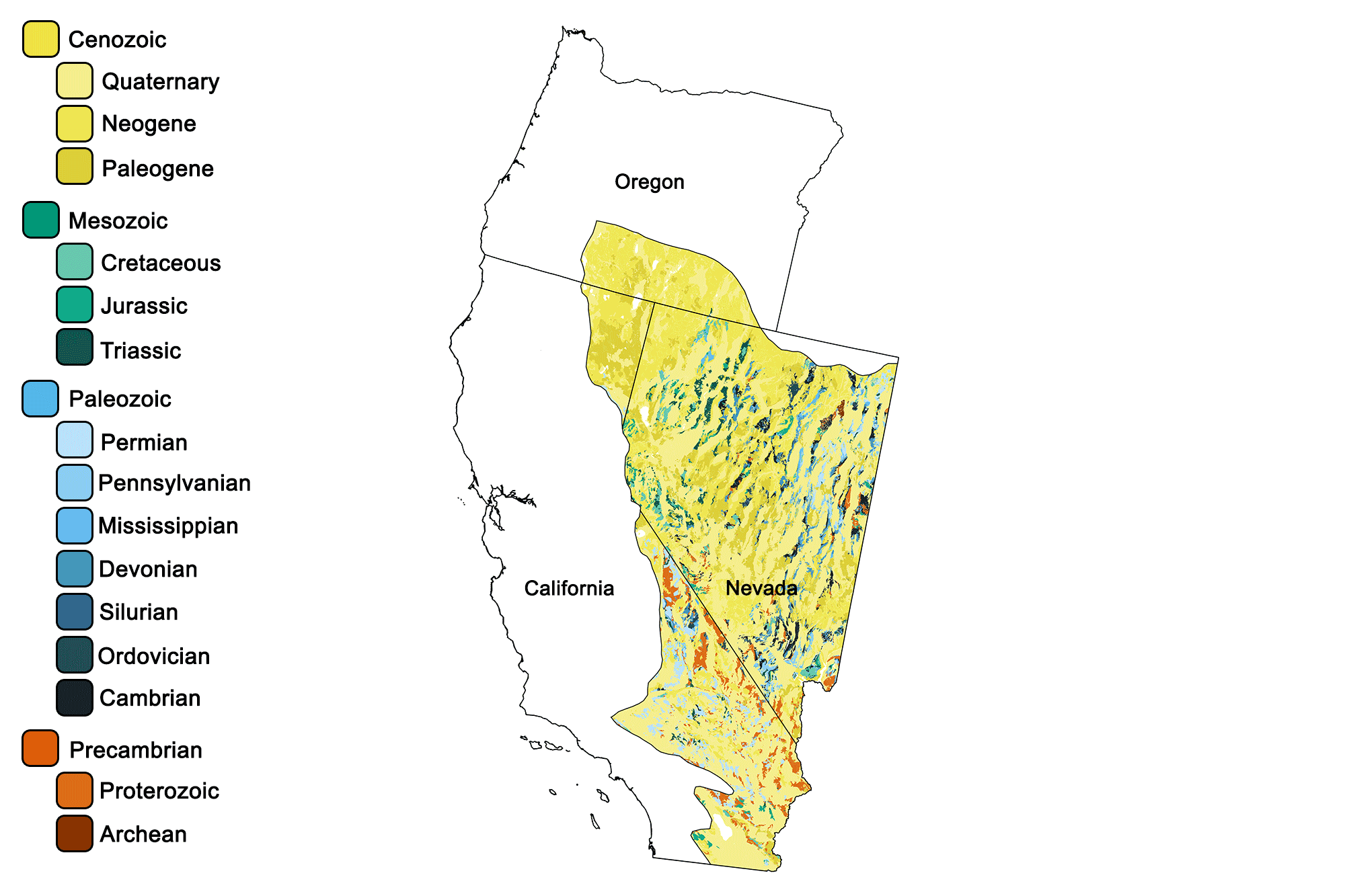

Geologic map of the Basin and Range region of the western United States showing maximum ages of mappable units. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project developed using QGIS and USGS data (public domain) from Fenneman and Johnson (1946)and Horton et al. (2017).

Overview

While the formation of the Basin and Range province is a recent event that began only 30 million years ago, the bedrock that makes up the up-thrust ranges and down-dropped basins is very old. Since its formation, the bedrock of the basins has been covered by young deposits such as loose sediment washed down from the mountains and evaporite deposits from dried-out lakes. The ranges, however, expose rocks whose ages span from Precambrian to Cenozoic. Many of the sedimentary rock layers exposed in the mountains of the Basin and Range are the same as the rocks exposed by the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, such as the Coconino Sandstone, Hermit Shale, and Kaibab Limestone, all of which are Permian in age.

Precambrian

The oldest rocks in the Basin and Range can be found in southern Nevada and the eastern Mojave Desert of California. They include granite as well as 1.7-billion-year-old metamorphic rocks such as gneiss, schist, and marble. The Pahrump group of rocks in Death Valley and nearby Nevada contains limestone in which stromatolites may be found.

Paleozoic and Mesozoic

The dark gray limestone of the Bonanza King Formation, which may be observed near Las Vegas, Nevada, formed in the Cambrian sea during a time period when the land that is now the Western States was still completely submerged—or not even yet part of North America. Today, the Paleozoic limestone has been thrust over the younger Jurassic Aztec Sandstone along a reverse fault that was created in the Mesozoic when the western edge of North America became a convergent plate boundary. The red Aztec Sandstone gives Red Rock Canyon, California its name.

Red-colored Aztec Sandstone with cross-bedding at Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area in Nevada. Photograph by "otzberg" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

The sand that makes up this stone was deposited as sand dunes, which is evident from the cross-bedded layers that result from sand sliding down the side of a dune.

During the Mesozoic, subduction occurred along the western coast. The resulting volcanoes are long since gone, but the granite that formed beneath those volcanoes remains, especially in the western parts of the Basin and Range. The stacked towers of granitic boulders found in Joshua Tree National Park, the Granite Mountains of the eastern Mojave, and Granite Peak in Nevada are all examples of granitic intrusions that formed during the Mesozoic.

"Giant marbles" in Joshua Tree National Park photograph by Brocken Inaglory (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

Cenozoic

The formation of the San Andreas Fault around 30 million years ago ended the compression of southern California and Nevada, and a period of extension began, leading to the wide-spread formation of basins and ranges. The extensional forces thinned the crust, allowing magma to reach the surface, which resulted in a period of intense volcanism This volcanic activity continues to the present day. In addition to creating the faults that make up the fault-block mountains of the Basin and Range, the tension resulted in a period of intense volcanism, which continues today.

This volcanic activity gave rise to a wide variety of igneous materials. Hole in the Wall and Wild Horse Mesa of the eastern Mojave National Park provide evidence for an explosive eruption of rhyolitic ash, which created an ash-flow tuff.

Hole in the Wall ash-flow tuff, Mojave National Park, California. Photograph by Amanda Scheliga (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Ash-flow tuffs are the result of pyroclastic flows—explosions that contain pulverized rock and superheated gases, which can reach temperatures of up to 1000 °C (1830 °F). The violent expansion of hot gas shreds the erupting magma into tiny particles that cool in the air to form dense clouds of volcanic ash. The tremendous explosions that are necessary to create ash-flow tuffs are caused by rhyolitic magma, which is felsic in nature. High silica content makes the magma quite viscous, preventing gas bubbles from easily escaping, thus leading to pressure build-ups that are released by explosive eruptions. The ash flows from these violent explosions tend to hug the ground, eventually solidifying into tuffs. Tuffs and other pyroclastic materials are vesicular (porous) due to gases expanding within the material as it cools.

The largest deposit of ash-flow tuff in the West is the Bishop Tuff from California’s Long Valley Caldera eruption 760,000 years ago. The Bishop Tuff is pink in color, vesicular, and contains pieces of pumice.

People examining the Bishop Tuff in California. Photograph by "brookpeterson" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NoDervis 2.0 Generic license).

Close-up view of the Bishop Tuff. Photograph by "Geo Rising" (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Along the Owens Gorge, just north of Bishop, California, the Bishop Tuff can be found in columnar joints.

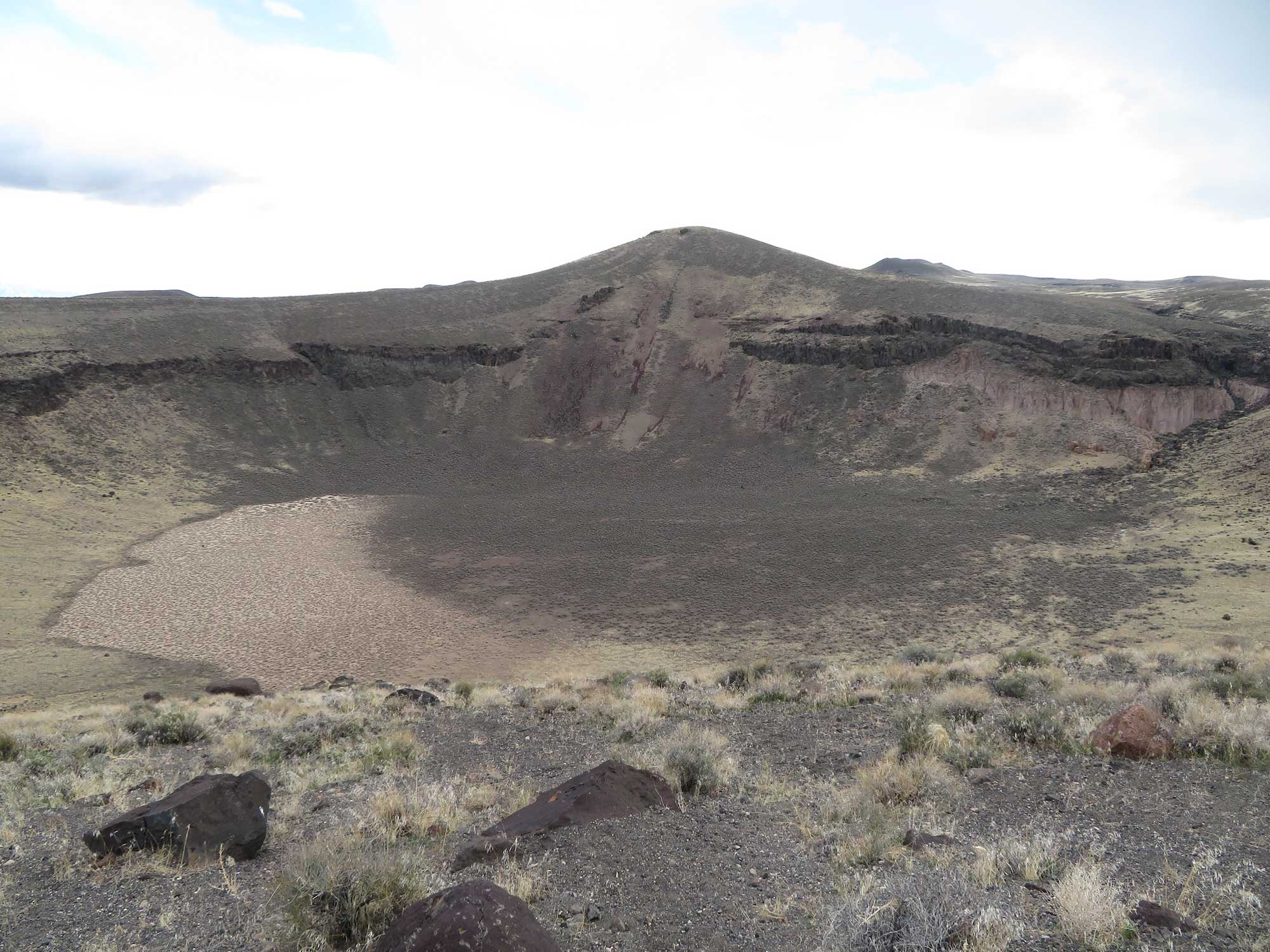

Not all volcanic rocks of the Basin and Range were created under such explosive conditions. Mafic magmas, which create rocks such as basalt, are less viscous and therefore can flow more easily. These gentler, effusive eruptions create features such as cinder cones and basalt flows. Lunar Crater in Nevada contains cinder cones and basalt lava flows that date from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, 20,000 years ago. Amboy Crater, Pisgah Crater, and the Cima Volcanic fields of the eastern Mojave also produced basalt and scoria.

Lunar Crater, Nevada. Photograph by Ken Lund (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

The Basin and Range also contains younger sedimentary rocks. Because the region is part of the Great Basin, water does not flow to the ocean, but instead evaporates from many playa lakes in the basins. At Mono Lake, a large playa lake located in Mono County, California, bubbling hot springs create a spongy limestone below the water called tufa. Because the water level of the lake has fallen, some of these tufa deposits, which formed thousands of years ago, are now visible and form towers on the lake's modern shore.

Tufa towers at Mono Lake, California. Photograph by Fred Moore (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals.

Earth@Home: Introduction to Rocks.

Earth@Home: Geologic time scale.

Earth@Home: Geologic maps.

Earth@Home Virtual Collection: Rocks (Virtual rock collection featuring 3D models of rock specimens sorted by type.)