Spotlight: Overview of the rocks of the Columbia Plateau and Basin and Range regions of the northwest central United States in Idaho.

Topics covered on this page: Columbia Plateau; Basin and Range; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Rocks of the Northwest Central US" by Lisa R. Fisher and Bryan Isaacs, chapter 2 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northwest Central US (published in 2015 by The Paleontological Research Institution and edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby). The book was adapted for Earth@Home web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated September 21, 2022.

Image above: Tower of basalt at Craters of the Moon National Monument in Idaho. Photograph by Harald Felgner (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

Rocks of the Columbia Plateau

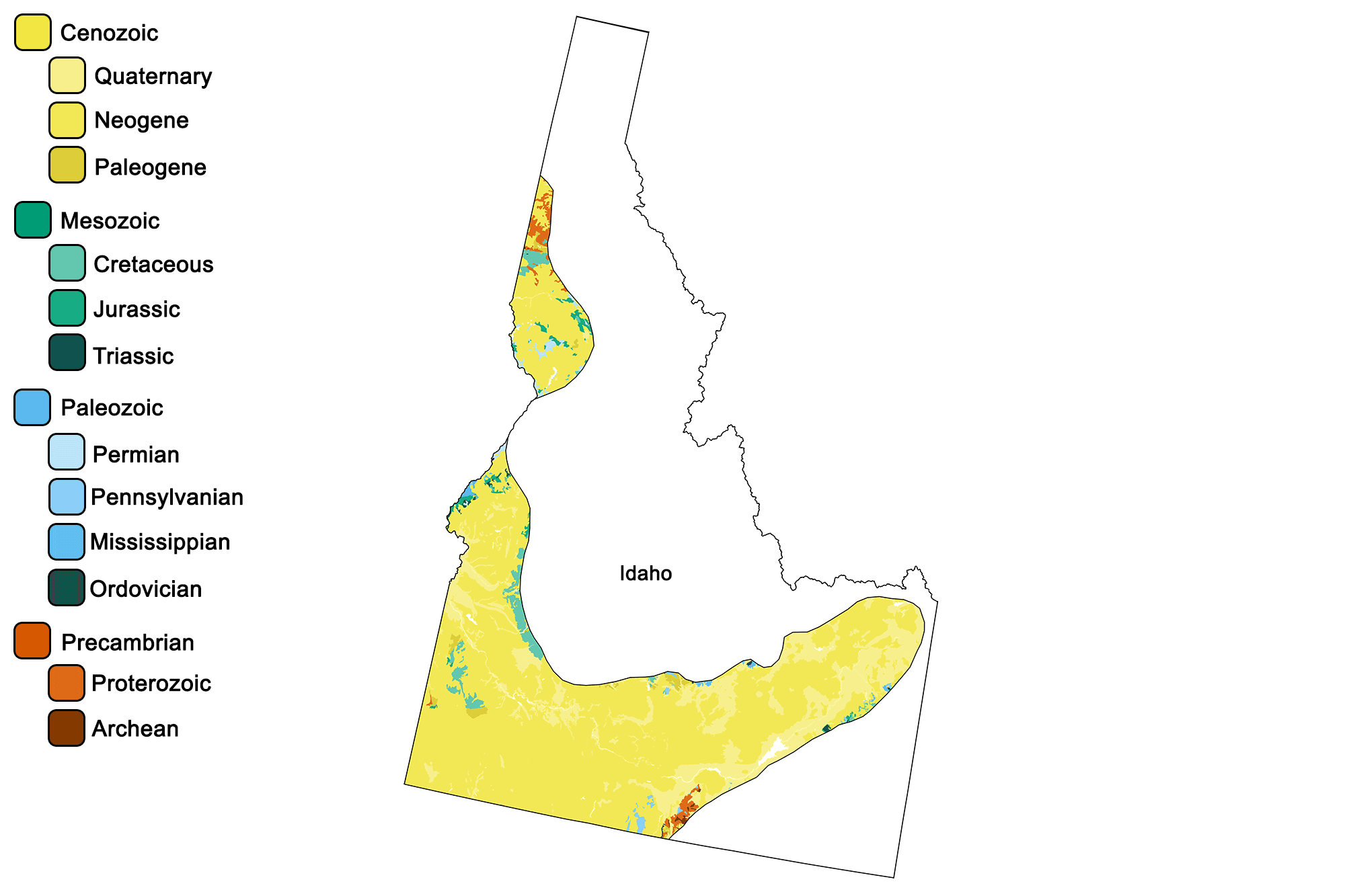

Geologic map of the Columbia Plateau region of the northwest-central United States showing maximum ages of mappable units. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project developed using QGIS and USGS data (public domain) from Fenneman and Johnson (1946)and Horton et al. (2017).

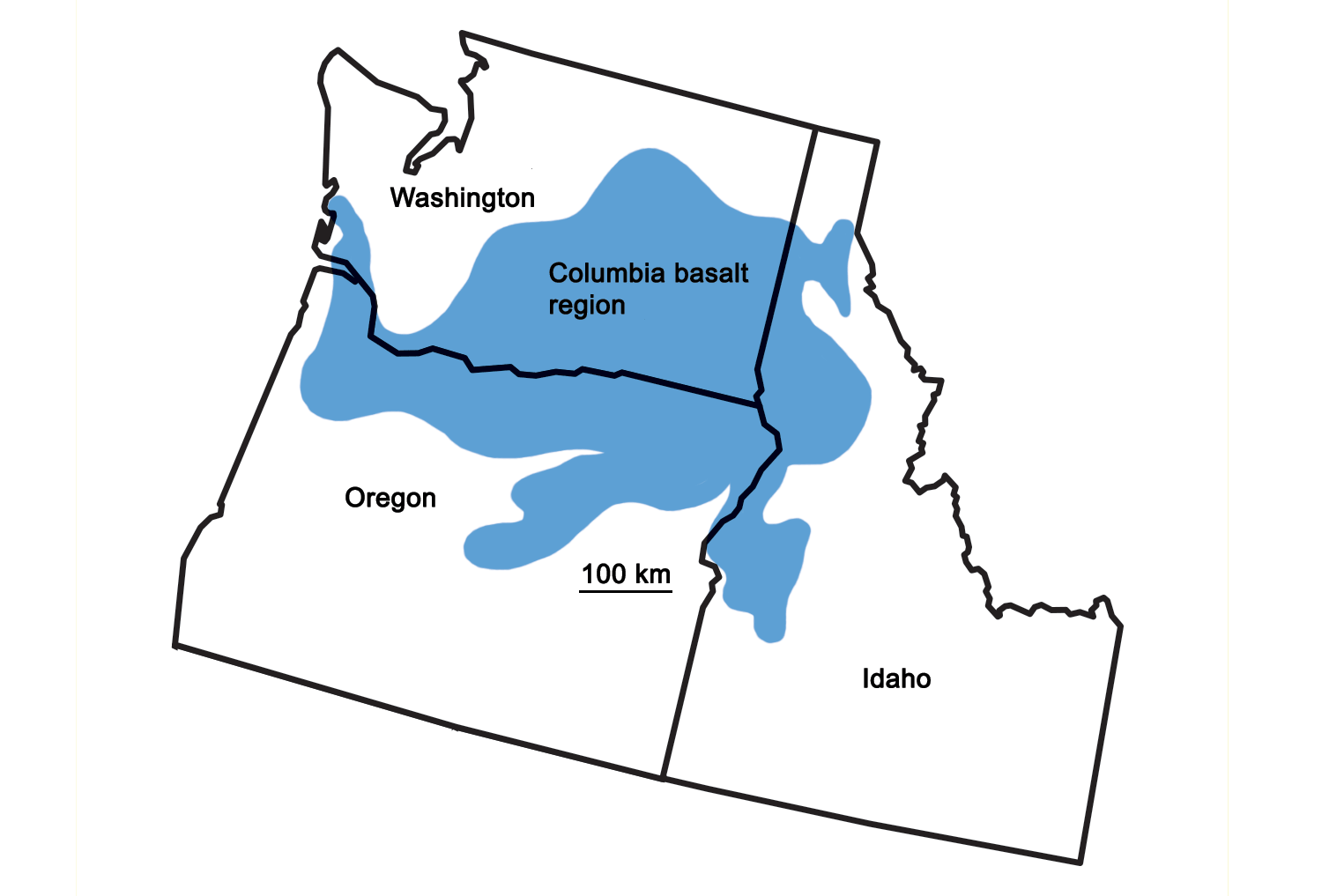

The Columbia Plateau, also known as the Columbia Basin, is the site of one of the largest outpourings of lava that the world has ever seen. The Columbia Plateau flood basalts are a notable example of a “Large Igneous Province,” where vast volumes of basalt are erupted over a relatively short period of time. Such a high volume of basaltic lava is erupted that the lava flows flood the land’s surface. Between 15 and 6 million years ago, basaltic lava flooded approximately 163,000 square kilometers (63,000 square miles), covering large parts of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Extent of the Columbia Basin Flood Basalt. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, modified for the Earth@Home project.

The thickness of the lava flows reached 1800 meters (6000 feet), burying almost all of the older rock in the area. Geological evidence suggests that many of these flows advanced over preexisting topography at a rate of five kilometers per hour (three miles per hour). This was made possible by the fact that basaltic lava erupts at a temperature of greater than 1100°C (2000°F), yielding a very hot and fluid form of lava that would have quickly inundated existing landforms.

The Columbia Plateau in western Idaho is uniformly covered with basalt, although over geological time, a large degree of faulting and warping has altered once nearly uniform elevations to a range of 60 to 1500 meters (200 to 5000 feet). The basalt flows found in this region commonly exhibit spectacular examples of columnar jointing. Large areas of flood basalt are generally associated with mantle hot spots. In this case, they are associated with the Yellowstone hot spot, whose trail from Oregon to Wyoming has produced the Snake River Plain. As the North American plate passed over the hot mantle plume, melting the base of the crust and producing large volumes of magma, the hot spot’s eruptive center moved northeastward across Idaho. The rocks of the Snake River Plain cut across both the older Rocky Mountain and Basin and Range regions of Idaho. The plain is deeply filled with 30 to over 300 meters (100 to over 1000 feet) of rhyolite and basalt. Thick layers of rhyolite are generally capped by basalt on the surface—smaller basaltic eruptions tended to continue long after a major rhyolitic caldera eruption. Deeper rocks are seen in drillhole cores, but there are many places where the surface basalts or lava fi elds can be seen. Craters of the Moon National Monument is a lava field where basalts have been erupted over the last 15,000 years; the youngest flow there is only 2000 years old.

A lava field at Craters of the Moon National Monument, Idaho. Photograph by Neal Wellons (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license).

Visitors can see flows, lava tunnels, spatter cones, and other volcanic features. Hell’s Half Acre, Shoshone, Cerro Grande, and Wapi are also well-known lava fields in the plain. In addition to lava flows, eruptions from the Yellowstone hot spot often generated enormous clouds of ash created when rhyolite magma was erupted as tiny molten particles. The ash was buoyed through the air by hot gases and blanketed hundreds of kilometers (miles) of land. As it condensed, it solidified into thick layers of tuff.

The Owyhee Canyonlands of southwestern Idaho cut through the Snake River Plain’s volcanic units, revealing layers of basalt, rhyolite, and welded tuff. Photograph by the Bureau of Land Management (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

Not all features of Idaho’s Columbia Plateau are related to igneous activity. As the Cordilleran Ice Sheet retreated back into Canada at the end of the ice age, meltwater ponded in lakes of all sizes. One of the largest glacial lakes was Glacial Lake Missoula in Montana, which was dammed by the ice sheet. When the ice dam failed, the lake was released in a catastrophic flood. The resultant landforms from this violent flood event carved deep channels into the terrain and left giant ripple marks, potholes, and boulders in the Channeled Scablands of northern Idaho and western Washington.

Rocks of the Basin and Range

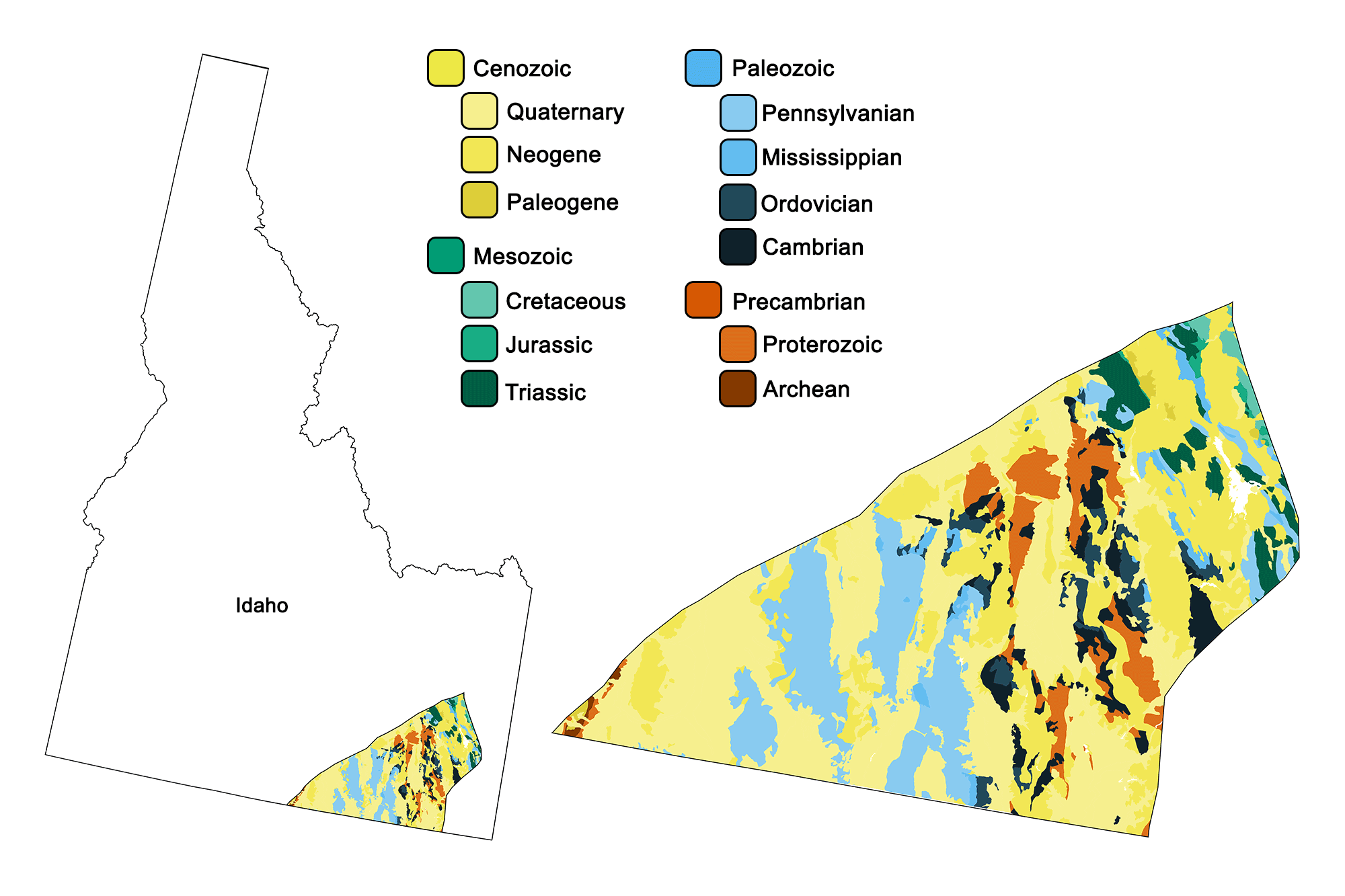

Geologic map of the Basin and Range region of the northwest-central United States showing maximum ages of mappable units. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project developed using QGIS and USGS data (public domain) from Fenneman and Johnson (1946)and Horton et al. (2017).

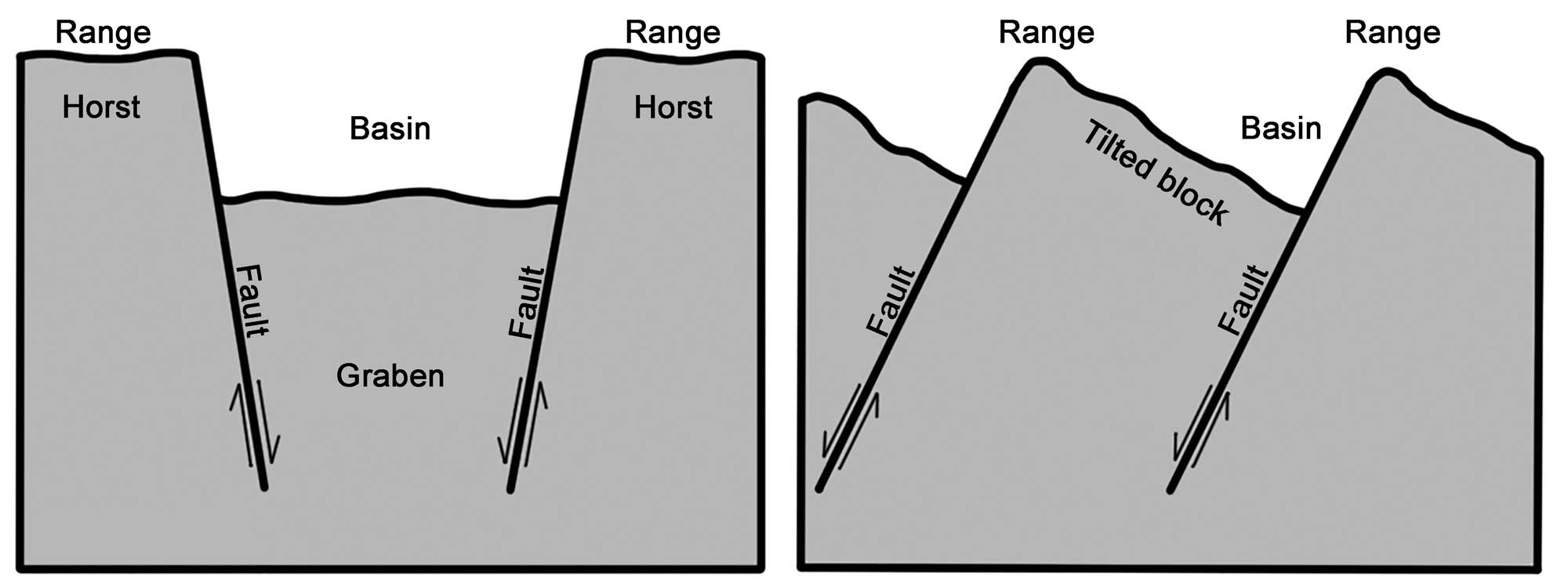

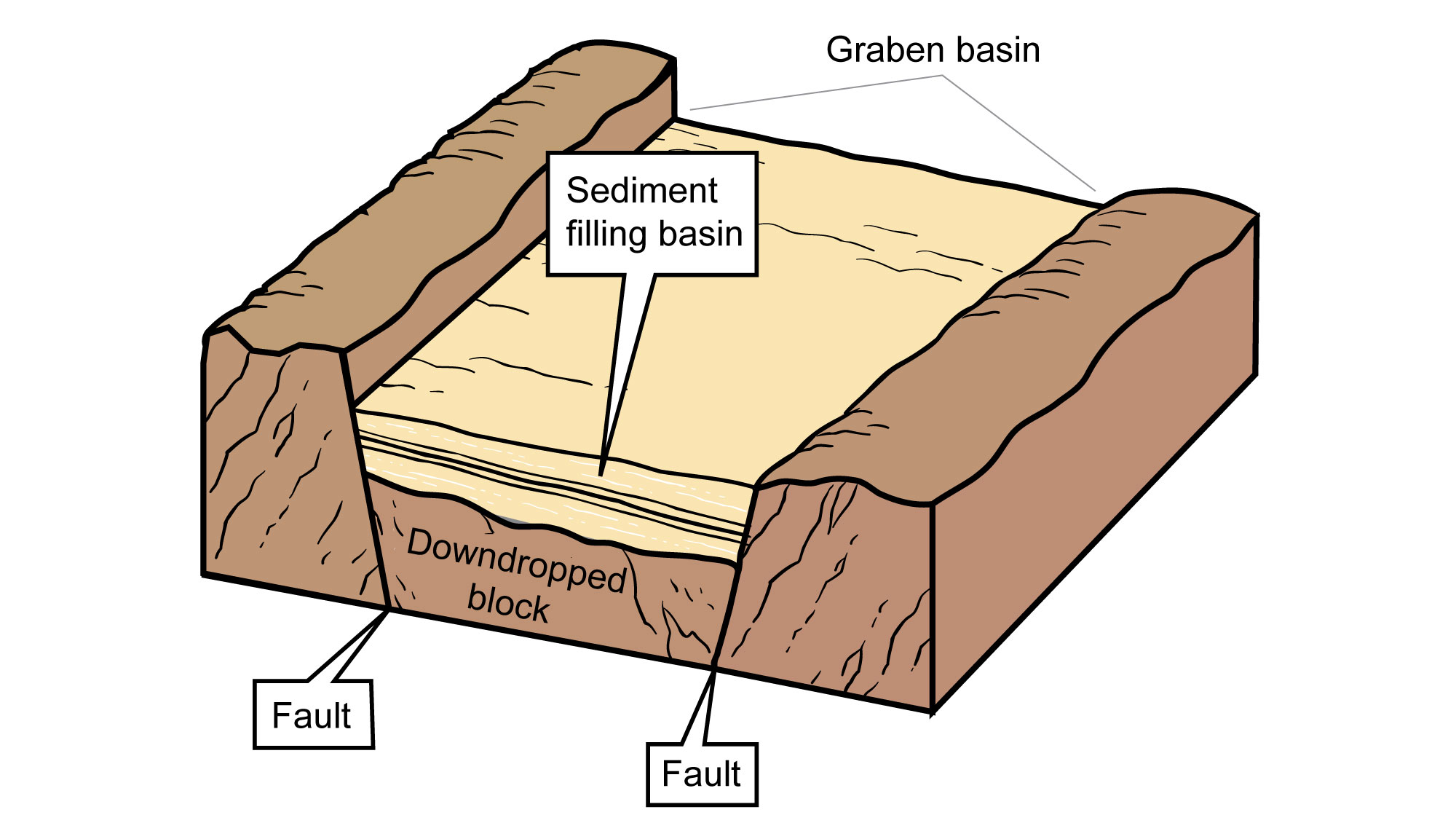

A tiny corner of the Basin and Range region—a huge physiographic region that extends from southeastern Oregon to west central Mexico—extends into the Rocky Mountains of southeastern Idaho. While the formation of the Basin and Range is a recent event that began only 30 million years ago, the bedrock that makes up the region’s up-thrust ranges and down-dropped basins is very old. In this tiny area of Idaho, rocks can be found from nearly all periods of the Phanerozoic. This is largely because the region’s most recent geologic activity involved crustal extension that has exposed many deeper, older layers. During the Paleogene, magma upwelling from the mantle weakened the lithosphere, lowering its density. This stimulated uplift, stretching the bedrock in an east-west direction. The crust along the Basin and Range stretched, thinned, and faulted into some 400 separate mountain blocks. Movement along the faults led to a series of elongated peaks and down-dropped valleys, also called horst and graben landscapes. In a manner similar to books toppling when a bookend is removed from a shelf, the blocks slid against each other as they filled the increased space.

Alternating basins and ranges were formed during the past 17 million years by gradual movement along faults. Arrows indicate the relative movement of rocks on either side of a fault. Image by Wade Greenberg-Brand, adapted from original image by the USGS; modified for the Earth@Home project.

Since the region’s formation, the bedrock of the basins has been covered by young deposits, including loose sediment washed down from the mountains and evaporite deposits left behind in dried-out lakes. The ranges, however, particularly the Sevier Orogenic Belt (also known as the “Overthrust Belt”), expose rocks whose ages span from Precambrian to Cenozoic. The Basin and Range’s Paleozoic rocks, a succession of sandstones, limestones, and shales, were deposited on the western shore of North America during the Cambrian to the Mississippian. This was followed during the Pennsylvanian to the Permian by a transition to shallow and evaporating seas, which deposited sandstones, mudstones, limestones, and phosphate-rich rocks. Mesozoic rocks include red beds, sandstones, mudstones, and limestones of the Dinwoody, Nugget, Twin Creek, Morrison, and Stump Formations. Good outcrops of these rocks can be seen in uplifted ranges such as the Bear and Aspen Range. These Paleozoic and Mesozoic sediments were thrusted during the Sevier Orogeny, then involved in the Basin and Range style of extension during the Paleogene. Valleys formed by this extensional faulting were filled with later Cenozoic sediments. Younger rocks from the Cretaceous and the Cenozoic cover the valley floor, filling the region’s basins.

Basin fill in the Basin and Range. Image by Jim Houghton, modified for the Earth@Home project.

These rocks are mainly conglomerates, sandstones, and mudstones originating from erosion of the nearby uplifts. In the case of the Idaho Basin and Range, the basin fills also include Cenozoic volcanic rocks produced by nearby volcanic activity on the Snake River Plain. Pleistocene deposits include glacial till, outwash, and glacial lake deposits. These gravels, sands, silts, and tills are mostly associated with glaciers in the adjacent Teton and Snake River Ranges of Wyoming.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals.

Earth@Home: Introduction to Rocks.

Earth@Home: Geologic time scale.

Earth@Home: Geologic maps.

Earth@Home Virtual Collection: Rocks (Virtual rock collection featuring 3D models of rock specimens sorted by type.)