Spotlight: Overview of the rocks of the Interior Highlands region of the South Central United States, including portions of Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Missouri; Arkansas and Oklahoma

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Rocks of the South Central US" by Richard A. Kissel, Alex F. Wall, and Andrielle N. Swaby, chapter 2 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the South Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated January 19, 2022.

Image above: Close-up view of Arkansas novaculite, a type of chert. Photograph by James St. John (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

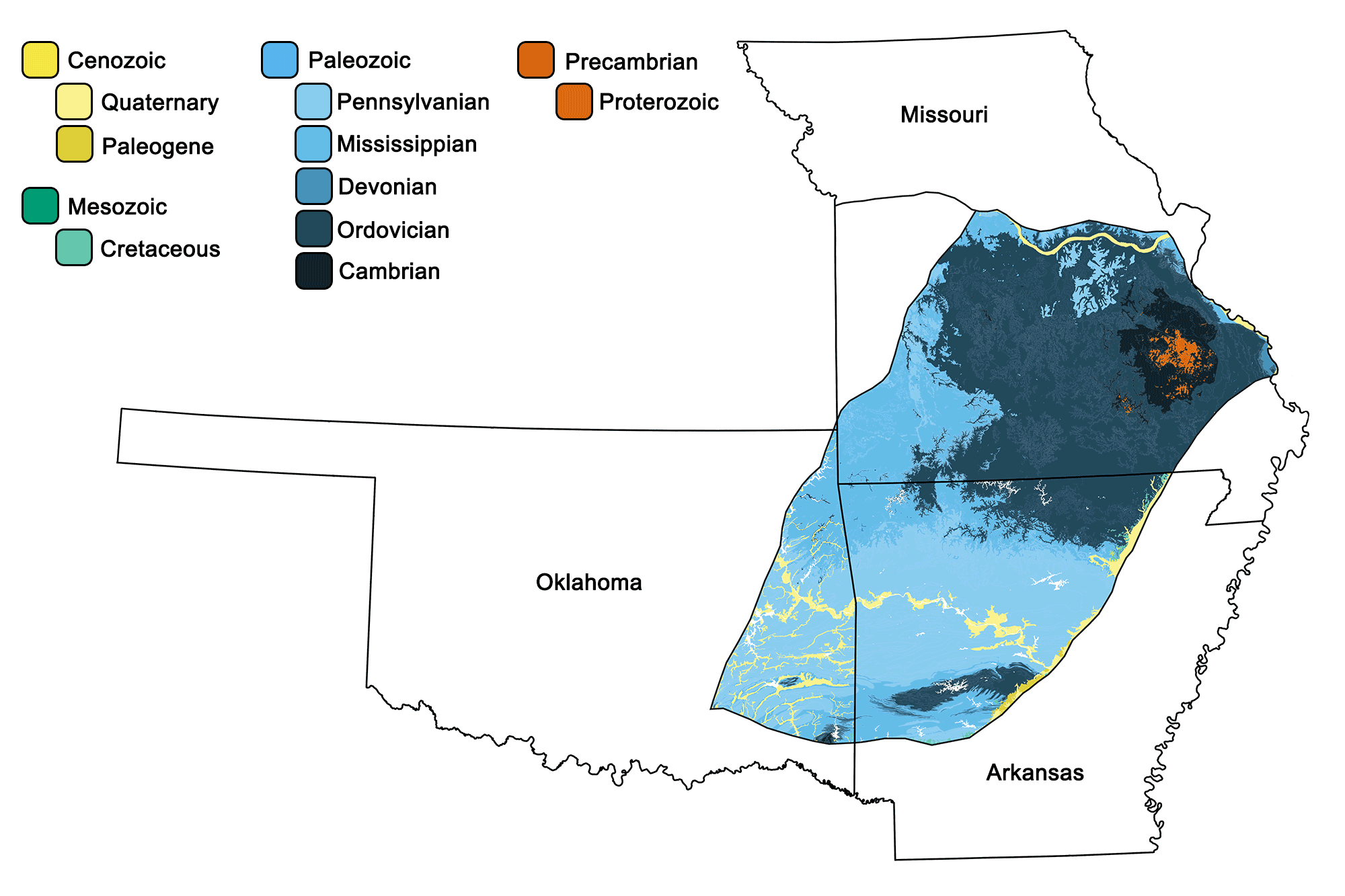

Geologic map of the Interior Highlands region of the South-Central United States showing maximum ages of mappable units. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project developed using QGIS and USGS data (public domain) from Fenneman and Johnson (1946) and Horton et al. (2017).

Overview

The mountainous regions of the Interior Highlands are dominated by uplifted sedimentary rock deposited within shallow seas, though the oldest rocks of the area are igneous in nature.

Missouri

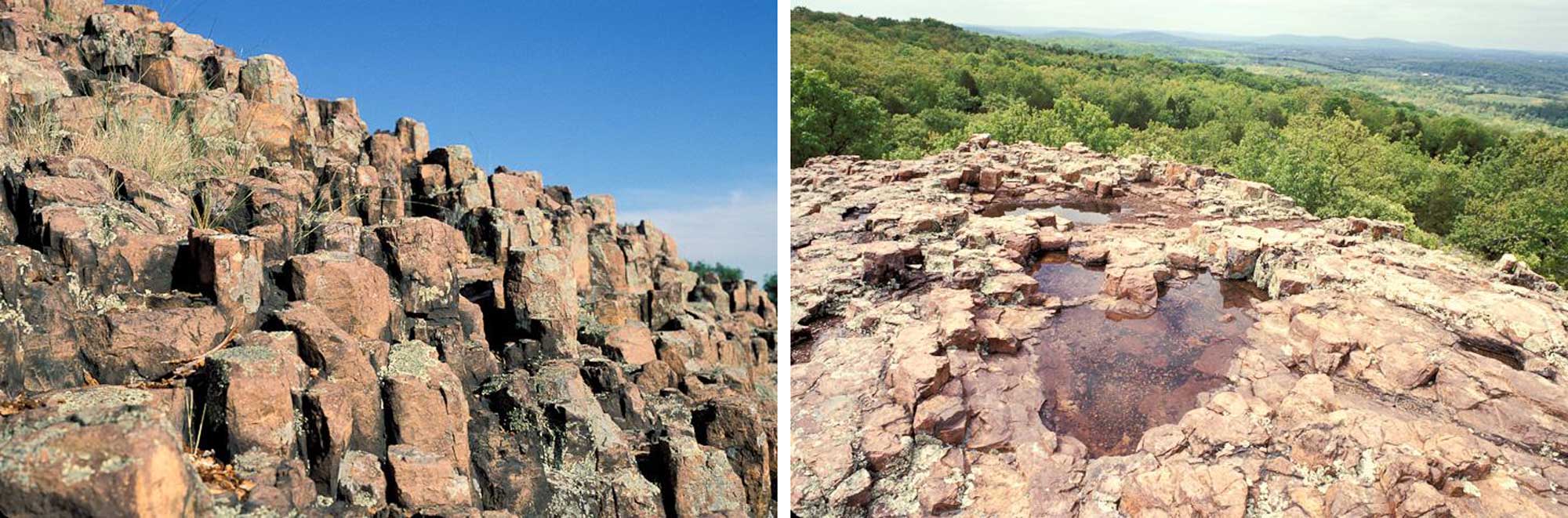

The core of the Interior Highlands is made up of a Proterozoic mountain range that formed around 1.5 billion years ago. Today, these units—a suite of igneous rocks—crop out within the Saint Francois Mountains in southeast Missouri across an area of 13,000 square kilometers (5000 square miles). The oldest of these rocks are composed of rhyolite flows dating to 1.5 billion years ago. In some of these flows, slower cooling led to the formation of larger crystals—called phenocrysts—within the rhyolites. Hughes Mountain, a rhyolite edifice in the southeastern Saint Francois Mountains, is composed of intrusive rhyolites that fractured into columnar joints while cooling.

The Devil’s Honeycomb, an outcropping of columnar jointed rhyolite in Hughes Mountain State Natural Area. Both photographs by Cliff White, Missouri Department of Conservation (Wikimedia Commons, left photo, right photo).

The Saint Francois Mountains also contain slightly younger intrusive granite that formed between 1.5 and 1.25 billion years ago. This granite is exposed in Elephant Rocks State Park (so named for a string of massive boulders that superficially resemble a chain of elephants), where spheroidal weathering has smoothly worn the ancient rocks away along preexisting fractures. The largest “elephant” in the park weighs 680 tons and is 8 meters (27 feet) tall, 7.6 meters (25 feet) long, and 5 meters (17 feet) wide.

The “elephant rocks” at Elephant Rocks State Park, Missouri. Photograph by "Fredlyfish4" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license; image cropped and resized from original).

In addition to rhyolite and granite, gabbro and basalt are common within the Saint Francois Mountains, with the latter being most commonly found in the form of dikes.

The Paleozoic rocks of the Interior Highlands consist of a suite of shale, sandstone, limestone, dolomite, and chert. During this time period, vast inland seas led to the deposition of sandstone near shore and shale and limestone in deeper waters, with coral reefs forming around the volcanic rocks of the Saint Francois Mountains.

Inland sea may sound like a contradiction in terms, but there is a very simple, yet important, distinction that differentiates it from other seas: an inland sea is located on continental crust, while other seas are located on oceanic crust. An inland sea may or may not be connected to the ocean. For example, Hudson Bay is on the North American plate and connects to the Atlantic and Arctic oceans, while the Caspian Sea is on the European plate but does not drain into any ocean at all.

Within the Paleozoic seaway that covered the Interior Highlands, sandstones, shales, carbonates, and chert accumulated. Deposits of shallow-water carbonates formed throughout the Paleozoic, with episodes of sea level regression and erosion occasionally disrupting their deposition.

The Ozark highlands in Missouri represent an uplifted plateau that formed during the late Paleozoic Ouachita Orogeny. Erosion of these newly formed uplands led to the deposition of clastic sediment in basins to the north and south of the plateau. A colorful form of chert, called mozarkite, is also plentiful in the Ozarks and is the official state rock of Missouri.

3D model of the form of chert called mozarkite. Model by the Missouri State Department of Geography, Geology and Planning (Sketchfab).

Arkansas and Oklahoma

After the collision of North America and Gondwana during the Pennsylvanian, the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea led to significant changes within the South Central States. The epicontinental seas that dominated the landscape for the previous 200 million years were squeezed out of the region, and marine deposits were severely affected by tectonic forces from the surrounding, colliding continents. A rapid influx of clastic sedimentary rocks was followed by intense deformation.

In Arkansas and Oklahoma, this folding and faulting resulted in the Ouachita Orogeny, which produced the Ouachita Mountains. The uplift exposed millions of years of buried marine strata, as well as Precambrian-aged granites and rhyolites. Today, the tilting limestone beds of the area create a distinct landscape known as “tombstone topography.”

The Ouachita Mountains are distinctive in that tectonic-induced volcanism, metamorphism, and intrusion played minimal roles in their formation, although low-grade metamorphism did lead to the formation of novaculite from existing chert. Novaculite is dense and therefore resistant to erosion; its layers stand out as ridges in the Ouachitas.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals: https://earthathome.org/de/minerals/

Earth@Home: Here on Earth: Rocks: https://earthathome.org/hoe/rocks/

Earth@Home Virtual Collection: Rocks: https://earthathome.org/vc/rocks/ (Virtual rock collection featuring 3D models of rock specimens sorted by type.)