Chapter Contents

- Why We Need to Adapt and Build Resilience

- The Costs and Benefits of Adaptation

- Types of Adaptation Strategies

- Adaptation to Different Climate Hazards

- Climate Justice and Equity

- Summary and Additional Resources

- Activities for Climate Change Adaptation Chapter

Image above: Flooding from Hurricane Harvey, 2017. Photo by Jill Carlson via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

How much would it cost to implement the many different adaptation strategies that people have developed? An equally important question is what is the cost of not doing anything—what will it cost our society, health, economy, and quality of life if we do not prepare for the impacts of a changing climate?

In 2022, the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB) published a report with estimates of the financial impact of climate change on the US's Federal budget. The report concluded that "estimated damages from a subset of storms, floods, wildfires, and other extreme climate-related weather events have already grown to about $120 billion a year" in the previous five years, and the OMB estimated that by the end of the 21st century, the Federal government's spending on climate disasters in the form of crop insurance, wildland fire suppression, health impacts, and coastal disasters will increase by $25 - $128 billion. [US OMB, 2022]

The same report also assessed a decline in Federal tax revenues resulting from economic decline due to climate change. They found that “In a scenario resulting in three degrees Celsius warming, the top end of the confidence interval (95th percentile) of Gross Domestic Product losses would result in 7.1 percent lower Federal revenue by 2100—equivalent to approximately $2 trillion per year in today’s [year 2022] dollars.” Climate change will lead to the Federal government needing to spend more money to help people recover from climate disasters, with less tax revenue coming in.

Video: "Can we afford (not) to stop Climate Change?" by Climate Adam (YouTube). This video focuses on climate change mitigation, but the concept of comparing the costs of climate action vs. inaction are similar for climate change adaptation.

Estimating Adaptation Costs

Many climate hazards come from processes that change slowly over time, but are extremely difficult to stop. For example, as the atmosphere warms due to the greenhouse effect, so does the surface of the ocean. Surface water mixes slowly with the rest of the ocean, and it will take hundreds of years for the ocean to absorb and mix the additional heat we are introducing to the system. Warmer water takes up more volume than colder water, so the ocean is expanding and sea level is rising. It is also rising due to the addition of water to the ocean from melting ice sheets and glaciers on land. The IPCC has concluded that by the year 2100, global sea level is projected to rise between about 0.5 to 1 m (about 1.5 to 3 feet), depending on the greenhouse gas emissions that result from the choices we make. [IPCC, 2021]

This presents a challenge to economists and policy makers who try to determine the cost of any particular adaptation strategy. For example, many large cities are located on ocean coasts and sit at or just above sea level. As these cities make plans for the upcoming decades they have to decide how they will deal with the sea level rise that is “in the pipeline.” City infrastructure such as airports, sea ports, roads, bridges, and subway systems and people living in coastal cities will be affected by rising sea levels, and they will need to plan for how to adapt.

Cities can select a variety of potential strategies. They can enhance shorelines with plants and natural structures that can absorb water and break waves, or build sea walls. They can develop building requirements that mandate new structures be built at higher elevations. They can develop plans to raise the elevation of sea ports and airports that are at risk, and relocate water treatment plants and other critical infrastructure. All of these options come with a cost—some much larger than others—but city planners also have to weigh these costs against the cost of inaction. If you are creating a city budget for the next year, future sea level rise may not seem like much of a threat. You may decide to do nothing and leave the sea level rise problem for future planners. You also may decide to build protective structures—at a high cost—and to justify these costs to the taxpaying public.

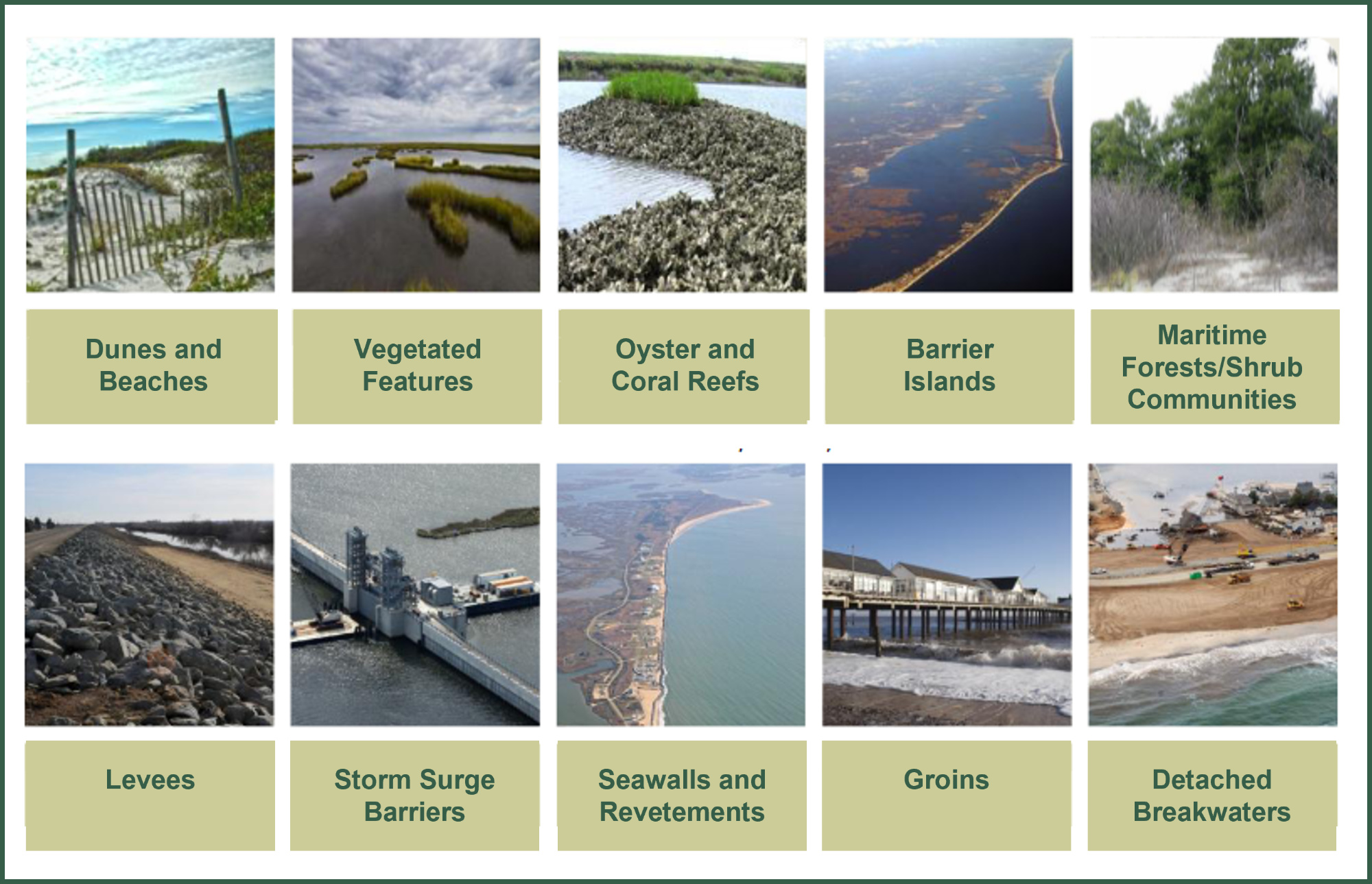

A variety of techniques for stabilizing and protecting coastal areas, both nature-based and structure-based. Image adapted from "Coastal Risk Reduction and Resilience: Using the Full Array of Measures" by the US Army Corps of Engineers (2013)

To make things even more difficult, many of these adaptation strategies and decisions have to be made in the face of uncertainty. How much will protective infrastructure cost? Who should pay for it? How high will the sea level rise? What type of storm surge should one prepare for? Are the frequency or severity of storm surges going to change in a warming climate? What should we do if sea levels start to rise quicker than we initially thought? What would happen if we did nothing?

Every adaptation strategy has its own set of uncertainties and potential tradeoffs. One example of a way to think about adaptation strategies and the potential costs and benefits comes from the US Department of Transportation: [US DOT, 2013]

Actions taken to adapt transportation systems to climate change have both costs and benefits. Costs can include increased construction cost associated with designing a bridge to be able to withstand more frequent and intense storms, training costs associated with process or equipment changes, or the increased cost of labor and materials if operation and maintenance activities change or occur more frequently. Costs can also include broader effects (whether positive or negative) on the economy and jobs.

The benefits of adaptation are the adverse impacts that are avoided; the more effective adaptation is, the greater the benefits. Benefits could include savings from avoiding the need to repair/replace assets. Benefits could also include impacts on quality of life from reduced traffic delays, avoided risks to human safety, avoided disruption of the flow of goods, etc.