Chapter Contents

- Why We Need to Adapt and Build Resilience

- The Costs and Benefits of Adaptation

- Types of Adaptation Strategies

- Adaptation to Different Climate Hazards

- Climate Justice and Equity

- Summary and Additional Resources

- Activities for Climate Change Adaptation Chapter

Image above of a Red Cross warming and charging station at Summit Middle School in Summit, NJ, in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Residents without power could come to the middle school to charge cell phones, have internet access, and keep warm. Image by Tomwsulcer (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Decisions about responding to climate change cannot be based on science and economics alone. They need to incorporate considerations of humans’ relationships and responsibilities to each other, and how people who have more resources to take action can help others who have less.

Climate actions also need to avoid putting an additional burden on people who are already struggling. For example, one way to adapt to an increased risk of flooding from heavy rains is to establish policies that do not allow people to move back into flood-prone areas following a destructive flood event. The most basic question may be whether the people affected agree with this and want to move. But beyond this, more affluent households are more likely to have the financial resources to find housing elsewhere and recover from flood events. In order for the policy not to put an undue burden on less affluent populations, they will need financial assistance to move elsewhere and recover.

What is Climate Justice?

Climate justice has two parts:

- Recognizing that climate change disproportionately affects socioeconomically vulnerable groups of people who often are the least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and have carried the heaviest societal burden of environmental hazards;

- Requiring action to protect and empower vulnerable and historically disadvantaged communities.

Climate justice can involve technological solutions but it is centered around people and includes listening; learning about the disproportionate impact of climate change and energy choices on historically disadvantaged communities; empowering communities that lack money, political influence, and other resources; and removing barriers that have prevented historically disadvantaged communities from taking the lead on making decisions that affect them.

Excerpt (3 minutes starting at 56:16) from video "A Sense of Place: Indigenous Perspectives on Earth and Sky – featuring Dr. Robin W. Kimmerer" by the Indigenous Education Institute (YouTube). The excerpt addresses the experience of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation with climate change and climate change resilience, and is from the Q&A part of a talk given Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and Distinguished Teaching Professor and Director, Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry. NOTE: The excerpt ends at 59:15, and is followed by a question about knowledge sharing, as well as other questions.

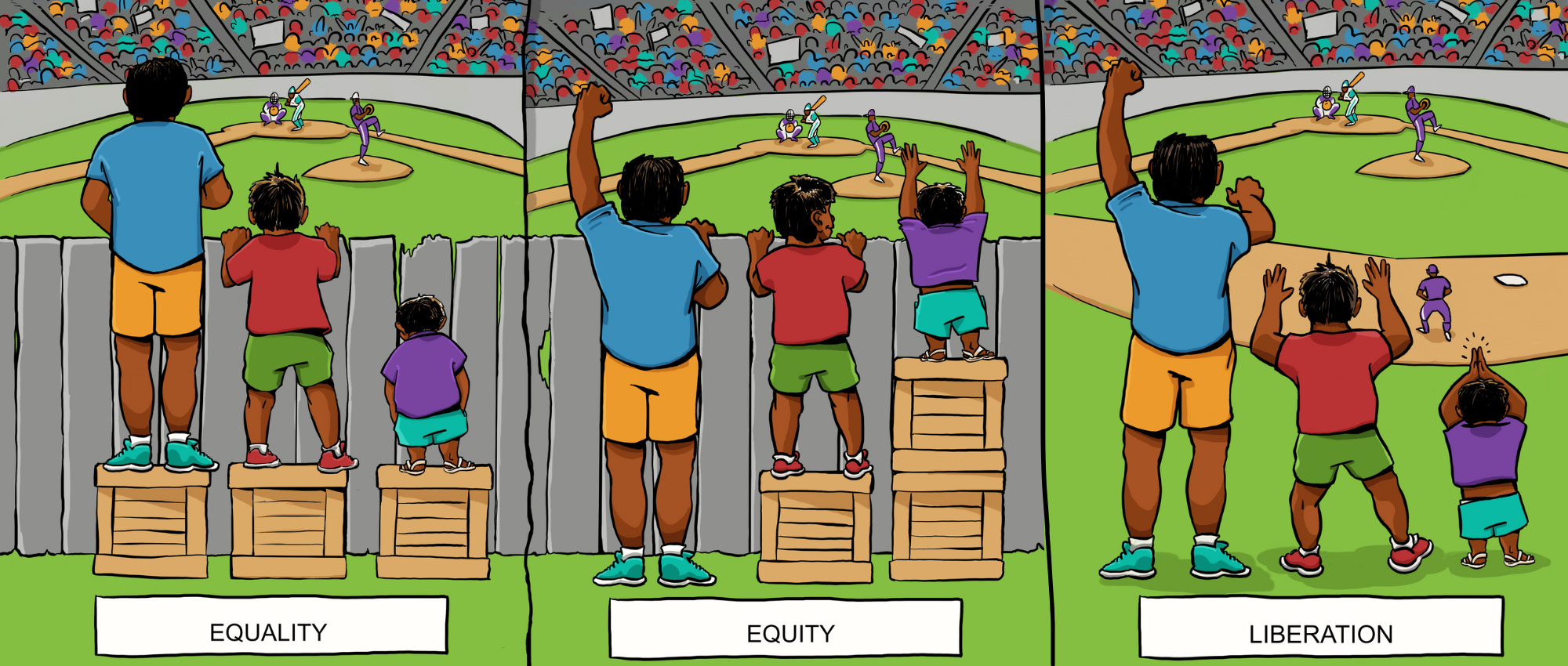

Equal treatment. Everyone gets the same supports.

Equitable treatment. Everyone gets the supports they need.

Liberation or Justice. The cause of the inequity is addressed. The barrier is removed, so no supports are needed.

Illustration: A collaboration between Center for Story-based Strategy & Interaction Institute for Social Change. Artwork by Angus Maguire. CC BY-SA 4.0

Intersecting Vulnerability Factors

The table below lists factors that lead to disparities in vulnerability to climate change in the United States. The different factors often intersect with and compound each other. The examples are not comprehensive, as climate change affects so many aspects of our lives that it is difficult to come up with a complete list.

In general, climate change exacerbates existing socioeconomic disparities, and hits those who are already vulnerable the hardest. Vulnerable groups of people often rely on systems that are less functional and closer to breaking, and these groups may experience climate impacts well before the wider population (for example, before a problem gets prioritized as an issue of general concern, or before something happens to mobilize widespread assistance.)

Income

People with low incomes may lack the financial resources to protect themselves, such as the ability to afford air conditioning during a heat wave, and a car to evacuate ahead of a severe storm. Financial pressures compound mental health stress from extreme weather events, and make it harder to recover.

Race/Ethnicity

Racial and ethnic minority groups in the U.S. often suffer from policies based on prejudice and other structural forms of discrimination. This has often led to living in proximity to sites with hazardous substances that can be released during flooding, and food insecurity and health care discrimination, leading to poor health that is worsened by climate hazards. People whose first language is not English may not get warnings of extreme weather.

Health

People with pre-existing medical conditions such as asthma, heart disease, and diabetes are more vulnerable to extreme heat and poor air quality caused by rising temperatures and wildfire smoke, which has now become a year-round threat in the western U.S., in part due to climate change. Severe storms and power outages can limit access to life-saving treatments and medication.

Age

Elderly people and very young children have higher risk of illness from extreme heat and poor air quality, which often results from burning fossil fuels and is exacerbated by higher temperatures. The elderly may lack social networks and other resources to help them during a severe storm or a wildfire.

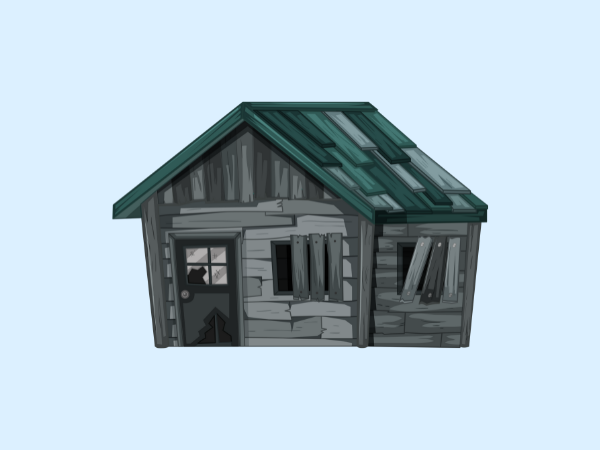

Housing

People who live in substandard housing are more likely to be exposed to extreme heat because of lack of insulation and air conditioning, and have needlessly high energy bills because of poor energy efficiency. They may also have more exposure to mold after flooding events. Impoverished neighborhoods often lack trees that could provide cooling and soak up stormwater (for example, see the Tree Equity Score mapping tool.)

Occupation

Outdoor workers are exposed to hazards made worse by climate change, such as extreme temperatures and storms, poor air quality, diseases from mosquitoes and ticks, and damage to infrastructure.

Disability

People who have disabilities in communication, cognitive functioning, or physical functioning may not receive emergency alerts during extreme weather events, and may struggle to act upon safety instructions. People who use wheelchairs may find it difficult to access wheelchair-accessible transportation during an evacuation.

Broadening the perspective to beyond just the U.S., global inequities are based on many of the same factors as within the U.S., such as income, race, housing, and occupation. On a global scale, wealthier nations generally have more resources available for adapting to climate change. Adaptation solutions may play out on national and international levels; for example, people who live in communities prone to flooding, wildfires, or drought may adapt by relocating their residences, businesses, public infrastructure, or farms. People may be forced to relocate if their homes and livelihoods are destroyed and they cannot rebuild them. Migration driven by climate hazards could take place within a country, or across borders.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as of 2021 "hazards resulting from the increasing intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, such as abnormally heavy rainfall, prolonged droughts, desertification, environmental degradation, or sea-level rise and cyclones are already causing an average of more than 20 million people to leave their homes and move to other areas in their countries each year." [UNHCR, 2021] Climate change and resulting lack or resources can also lead to violent conflict and political instability that turn more people into refugees who are looking for safety and stability.

"Refugees flee conflict sparked by climate change in central Africa" by PBS Newshour (YouTube)

Countries vary over orders of magnitude in the total amount of carbon dioxide they’ve emitted in the past as a country, how much they emit now, and how much they emit per capita. One of the challenges in creating international agreements on carbon emissions and adaptation efforts, and in creating domestic support for such agreements, is in resolving the real-world economic implications of decisions that, in principle, might take these sorts of factors into account.

Just Adaptation Solutions

Because climate change interacts with socioeconomic inequities that are already pervasive, complex, and difficult to repair, climate change adaptation solutions that are socially just can be challenging to implement successfully. Two important points to recognize are:

-

Climate change adaptation is inherently local and must be tailored to communities’ needs, because solutions that work for one community may not work for other communities.

- Investment is necessary in order to reduce risks from climate change.

In its 2022 report on climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identified several categories where public and private investment are needed in order to help people who are facing poverty: [J. Birkmann et al, 2022]

- Natural assets (e.g., mangroves, farmland, wetlands)

- Human assets (e.g., health, skills, Indigenous knowledge)

- Physical assets (e.g., mobile phone connectivity, housing, electricity, technology)

- Financial assets (e.g., savings, credit)

- Social assets (e.g., social networks, membership of organizations such as farmer cooperatives).

Example Solution: Community Gardens

An example of investment that promotes climate change resilience and climate justice is the support of community gardens. New York City, for example, had over 100 acres of land devoted to community gardens in 2019, and most are in neighborhoods where residents do not have nearby access to public parks. Permeable surfaces such as gardens play an important role in soaking up stormwater in cities, which is increasingly vital as heavy rainfalls become more frequent. EarthJustice, a nonprofit public interest environmental law organization, describes the benefits of New York City's community gardens:

"Community gardens are greenspaces designed and operated by New York City residents. With community members in charge, the gardens are uniquely adaptable and responsive to neighborhood needs. For instance, in neighborhoods with little access to fresh food, community gardens provide fruits and vegetables, as well as opportunities for community members to share information about healthful cooking. As the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated longstanding racial and economic disparities across New York City, community gardeners mobilized to support their neighbors by increasing production and distribution of fresh produce, which helps to keep immune systems strong.

Community gardens also contribute significantly to New York City’s sustainability efforts, providing ecosystem services such as flood mitigation, air filtration, heat reduction, and vital habitat for pollinators." [EarthJustice, 2022]

The type of investment and support that helps community gardens thrive includes financial support from city government and private funders, advocacy from non-profit organizations such as the New York City Community Garden Coalition, and legal support from organizations such as EarthJustice that work to get protected legal status for community gardens.

Example Solution: Affordable, Energy-Efficient Housing

Another example of a just solution is building affordable housing that incorporates energy efficient features such as insulation, heat pumps for energy efficient heating and cooling, and energy efficient appliances. These types of energy efficiency measures will reduce energy use and monthly energy bills, so this type of housing helps residents with low incomes because it is not just affordable to purchase or rent—it is also affordable to live in. This solution is both an adaptation and mitigation solution: it helps people adapt to extreme heat by providing air conditioning to those who might not otherwise afford it, and it reduces greenhouse gas emissions by reducing energy use.

Developers may need public or private investment to be able to build this type of affordable housing, such as government or private foundation grants and funds from private donors.

Photos of energy-efficient, affordable housing developed in Ithaca, NY by Ithaca Neighborhood Housing Services (INHS), a nonprofit organization that serves seven counties throughout the Finger Lakes and Southern Tier in New York State. INHS's description of this particular project, Holly Creek, states: "Completed in two phases, Holly Creek earned the ENERGY STAR LEED Gold Certification and was awarded the Housing Innovation Award by the U.S. Department of Energy. The homes sold at starting prices of $104,000, well below the county’s median price of $183,000." (Note: housing prices are from 2013.) Photos: INHS, used with permission.