Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Central Lowland region of the midwestern United States.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; Paleozoic fossils; Cambrian fossils; Krukowski Quarry; Ordovician fossils; Silurian fossils; Devonian fossils; Carboniferous fossils; Mazon Creek biota; Mazon creek flora; Mazon creek fauna; Cretaceous fossils; Pleistocene fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the Midwestern US" by Alex F. Wall and Warren D. Allmon, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Midwestern US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2014 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated October 25, 2023.

Image above: Crinoids (Pycnocrinus dyeri) from the Orodovician Arnheim Formation, Dent, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Introduction

The Paleozoic is well represented in the Central Lowland region of the Midwest from the Cambrian through the Pennsylvanian periods. Together, fossils from across the region record some of the most important chapters in life’s story. The Central Lowland’s fossils take us on a journey from when complex organisms first became abundant, through the development of reefs and other recognizable components of marine ecosystems, to the invasion of land. To the west, a few Cretaceous fossils of giant marine reptiles and sharks may be found. Terrestrial fossils from the most recent ice age, beginning just two million years ago, have also been discovered in every state in the Midwest, preserved in sediment left by the glaciers.

Paleozoic fossils

Cambrian fossils

The Cambrian period is represented in the Central Lowland by an irregular strip that cuts east and west through Wisconsin, crossing into neighboring parts of Minnesota and Michigan. The beginning of this period is marked by the relatively sudden appearance of an unprecedented diversity of creatures. Within a span of roughly 30 million years, all of the major animal groups that we know today, such as mollusks, arthropods, echinoderms, and vertebrates, appeared within the Earth’s oceans. This time of rapid diversification and evolution is known as the “Cambrian Explosion.” These new kinds of animals interacted with each other and their environments radically in new ways. It was during this time that animals quickly evolved a suite of innovations, including mobility, vision, and hard mineralized parts.

While the Cambrian period was the beginning of complex life, its cast of characters is very unlike the animals of today. Cambrian-aged rocks in Wisconsin and Minnesota preserve the hard parts of trilobites, brachiopods, trace fossils of worms, algae, and jellyfish, and the mysterious hyoliths. Hyoliths are animals with cone-shaped shells that existed throughout the Paleozoic Era. Their affinities to other animals are uncertain, with some scientists classifying them as mollusks and others placing them in their own phylum.

Trilobite pygidium (Dikelocephalus minnesotensis), Cambrian Trempealeau Formation, Washington County, Minnesota. Photo of USNM PAL 17863 by Department of Paleobiology (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

Burrows (Skolithos), Cambrian Mazomanie Formation, eastern Minnesota. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

The Krukowski Quarry

The Krukowski Quarry in central Wisconsin reveals an extraordinary fossil assemblage of Cambrian marine invertebrate trackways and jellyfish in cream-colored sandstone that looks like it formed on a beach. The Krukowski Quarry, near Mosinee, Wisconsin, is a locality famous for its unique preservation of trace fossils from a 510-million-year-old beach. Fossilized trackways found there give paleontologists clues about the organisms and the way they moved around under the shallow water.

Amazingly, Krukowski Quarry also contains fossilized traces of scyphozoan jellyfish. Preservation of such soft creatures is rare enough, but these are both the oldest and, at a diameter of up to 50 centimeters, several times larger than any other fossil jellyfish! At a time when few animals had hard parts, these jellyfish were likely top predators. Their extraordinary preservation seems to indicate that these unfortunate individuals had become stranded on the beach, long before any life (except perhaps bacteria) had colonized land.

Trace fossils (Climactichnites), Cambrian, Krukowski Quarry, Wisconsin. Photo by Kennethcgass (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Ordovician fossils

Ordovician fossils are found in all seven Midwestern states. Life in the tropical sea that covered much of the central United States at the time experienced a burst of diversity, which increased fourfold compared with that of the Cambrian. Beginning in the Ordovician and expanding through the rest of the Paleozoic, great reefs were formed by organisms like bryozoans, corals, algae, and sponges, which are found in rocks in the Central Lowland region. Bryozoans are an entire phylum of colonial marine animals, and during the Paleozoic, their erect, branching skeletons formed vast thickets that are fossilized in the Ordovician rock around Cincinnati. These reefs played a major role in forming the ecosystems that were also home to straight-shelled cephalopods, trilobites, bivalves, gastropods, crinoids, graptolites, brachiopods, and fish.

Trilobites and brachiopods, which had dominated the Cambrian period, expanded somewhat in diversity and abundance in the post-Cambrian. Trilobites (which probably fed on seafloor mud) developed defenses against threats from new kinds of predators and competitors: spines, acute vision, and the ability to swim or burrow.

Ice ages occurred at the ends of both the Ordovician and Devonian periods, dramatically affecting life in the then-tropical Central Lowland by sequestering water in polar ice sheets. This caused dramatic changes in sea level, which resulted in devastating mass extinctions, allowing new successions of organisms to come to the fore.

An alga (Buthograptus laxus) from the Ordovician Trenton Limestone, Wisconsin. Photo of USNM PAL 339997 by Frederic Cochard (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

Bryozoans and brachiopods, Ordovician Whitewater Formation, Indiana. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Rugose corals (Streptelasma corniculum) from the Ordovician Platteville Limestone, Wisconsin. Photo of YPM IP 547681 by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Upper (left) and lower (right) surface of a brachiopod (Leptaena) shell, Ordovician, Iowa. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Brachiopods, Ordovician Waynesville Formation, Warren County, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

A straight-shelled cephalopod, Ordovician Waynesville Formation, Warren County, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image reconfigured, cropped, resized).

"Fossil specimen of the cephalopod Actinoceras beloitense from the Ordovician Platteville Limestone of Ogle County, Illinois (PRI 70326). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 9 cm. Model by Emily Hauf." Source: Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab.

An enrolled trilobite (Flexicalymene meeki) in four views: from above (left), from the front (second from left) and from each side (two right photos), Ordovician Waynesville Formation, Franklin County, Indiana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image reconfigured, cropped, resized).

A starfish (Hudsonaster) from the Ordovician Platteville Limestone, Wisconsin. Photo of YPM IP 538069 by Jessica Utrup (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

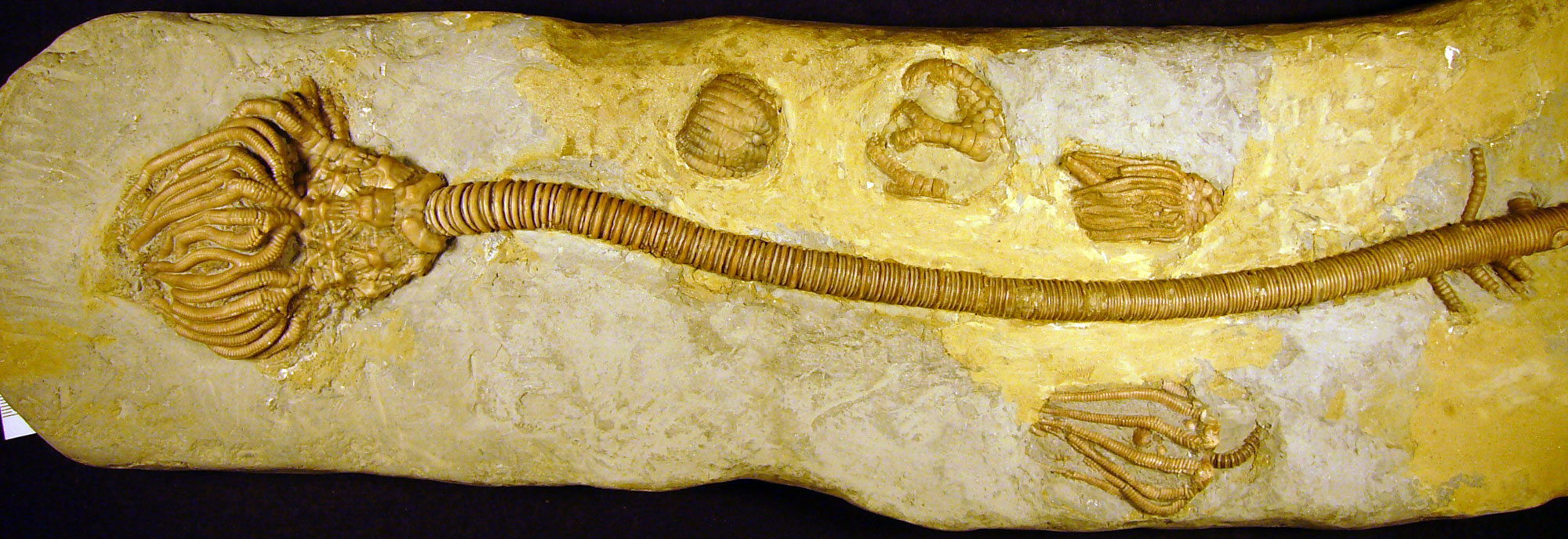

Crinoids (Iocrinus subcrassus) from the Ordovician McMillan Formation, Hamilton County, Ohio. Photo of USNM PAL 33475 by Bruce Martin (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

Silurian fossils

Through the Silurian and Devonian periods, reefs expanded across the shallow sea that covered the Midwest. While these reefs performed ecological functions similar to those of modern coral reefs, many of the animals that constructed them were very different. Now-extinct tabulate corals, like Halysites (found in Ohio), formed elaborate honeycomb-like colonies.

In Wisconsin, the Waukesha Biota, known from two quarries in Milwaukee County, is a fossil Lagerstätte (exceptionally preserved fossil deposit). This biota includes brachiopods, trilobites, soft-bodied arthropods, enigmatic conularids, a variety of worm-like animals, and graptolites.

A bryozoan (Fistulipora neglecta), Silurian, Illinois. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

The tabulate coral Halysites, Silurian Brassfield Formation, Ohio. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Internal molds of pentamerid brachiopods, Silurian Racine Formation, Grafton, Illinois. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Trilobites (Stenarocalymene celebra), Silurian, Jersey County, Illinois. Photo of USNM PAL 376740 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

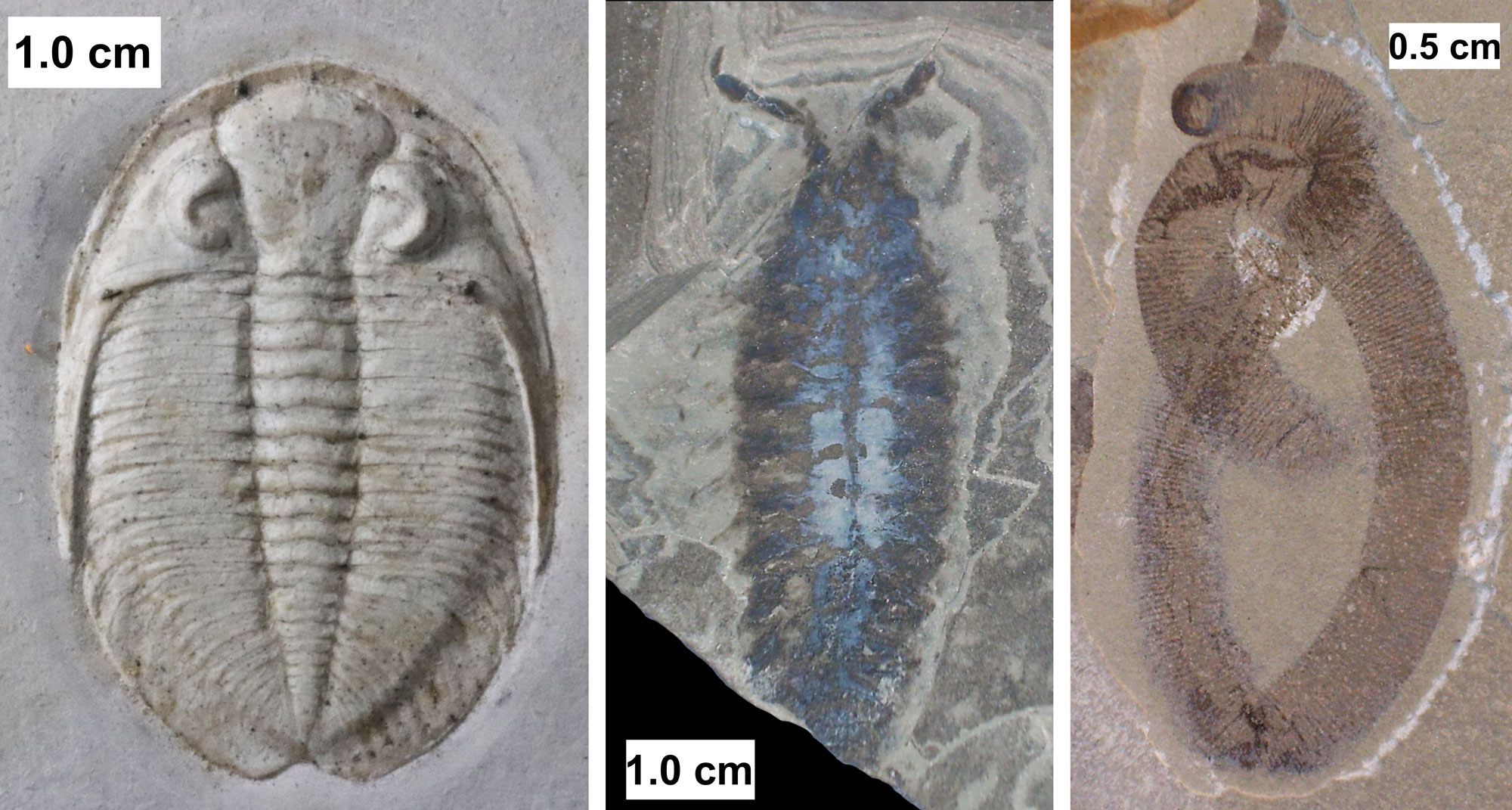

Fossils from the Silurian Waukesha Biota, Brandon Bridge Formation, southeastern Wisconsin. Left: A dalmatid trilobite. Center: An arthropod (Parioscorpio venator). Right: A worm (leech?). Photos by Kennethcgass (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image rotated and resized).

Devonian fossils

Devonian rocks occur in all states in the region, but are limited in extent in Minnesota and Wisconsin. The Cedar Valley Group in Iowa yields abundant remains of Devonian reefs composed of layered sponges called stromatoporoids. Michigan’s state rock, the Petoskey Stone, is actually a colonial rugose coral of the genus Hexagonaria that is found in Devonian-aged rocks (this reef-builder that is also the namesake of Coralville, Iowa). Other rugose corals were solitary, composed of only one coral polyp. All tabulate corals were colonial. The mass extinction event at the end of the Devonian left bryozoans as the major reef-building group until the Mesozoic.

The Silica Shale in western Ohio yields well preserved invertebrates like brachiopods and trilobites. A small sliver of fossil-bearing Devonian rocks of the Milwaukee Formation occurs in Wisconsin between Milwaukee and Sheboygan.

A stromatoporoid (Stromatopora), Devonian, Iowa. Photo of USNM PAL 89905 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

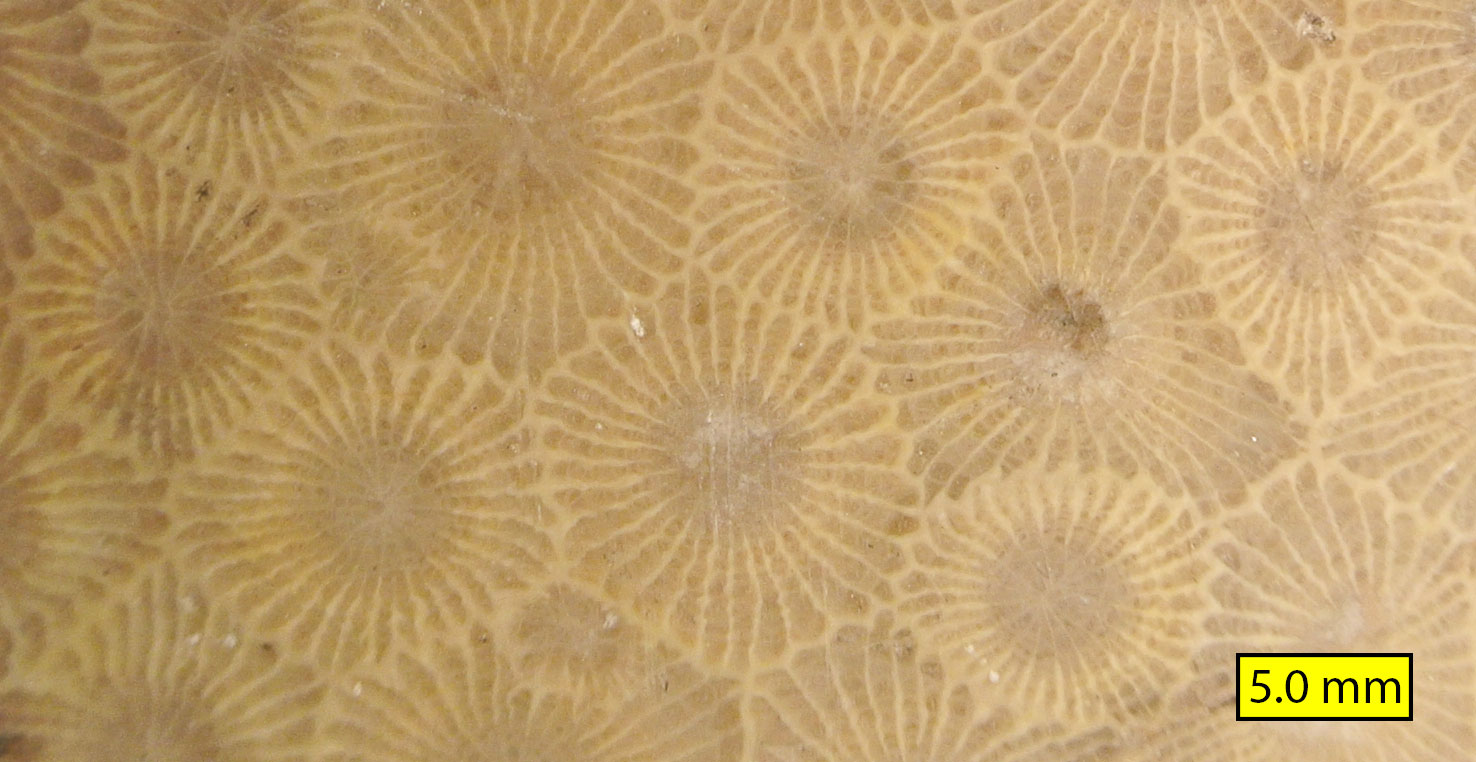

The colonial rugose coral Hexagonaria, Devonian, Michigan. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Detail of a Petoskey stone (Hexagonaria percarinata), Devonian, Michigan. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Bryozoans (Sulcoretepora) with brachiopods and crinoid columnals (stalk segments), Devonian Milwaukee Formation, Wisconsin. Photo by Kennethcgass (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

A brachiopod (Mucrospirifer mucronatus), Devonian Silica Shale Formation, Paulding County, Ohio. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

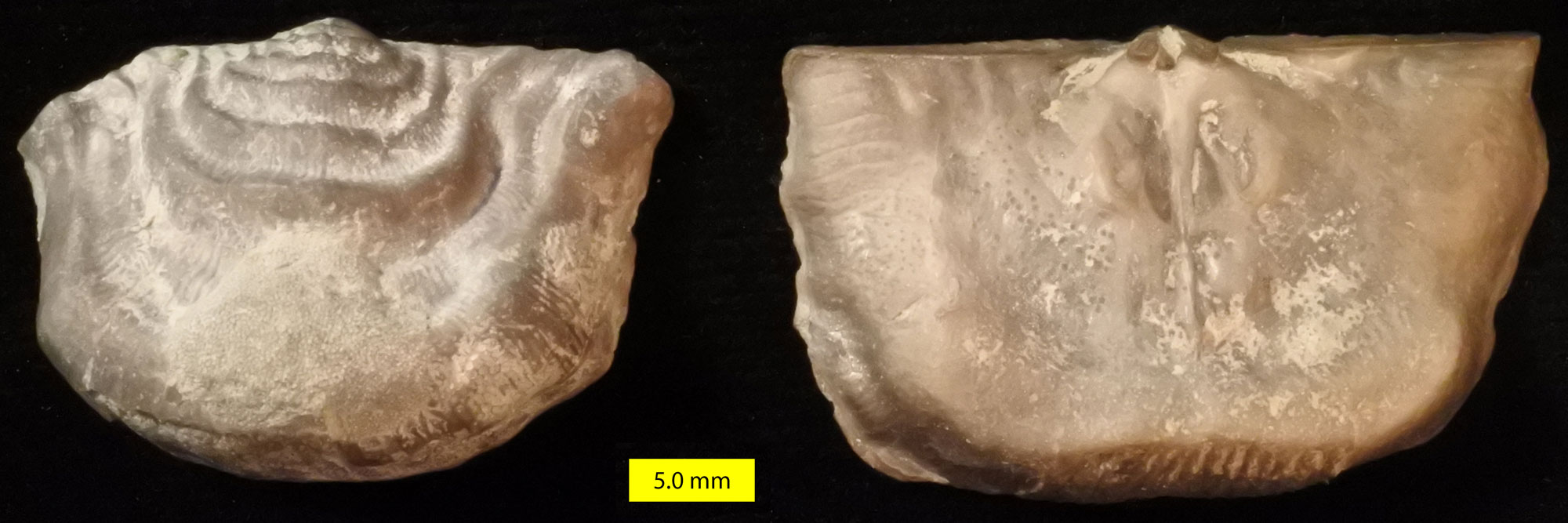

Lower (left) and upper (right) surfaces of a brachiopod (Strophodonta demissa), Devonian Silica Shale Formation, Michigan. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

Brachiopod (Schizophoria) in four views, Devonian Milwaukee Formation, Wisconsin. Photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication). Photo by by Kennethcgass (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Nautiloid cephalopods from the Devonian Milwaukee Formation, Wisconsin. Left: A straight-shelled cephalopod (Acleistoceras whitfieldi). Right: A coiled cephalopod (Gyronaedyceras eryx). Left photo and right photo by Kennethcgass (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Trilobites (Phacops) from the Devonian Silica Shale, Ohio. Photo of USNM PAL 482068 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

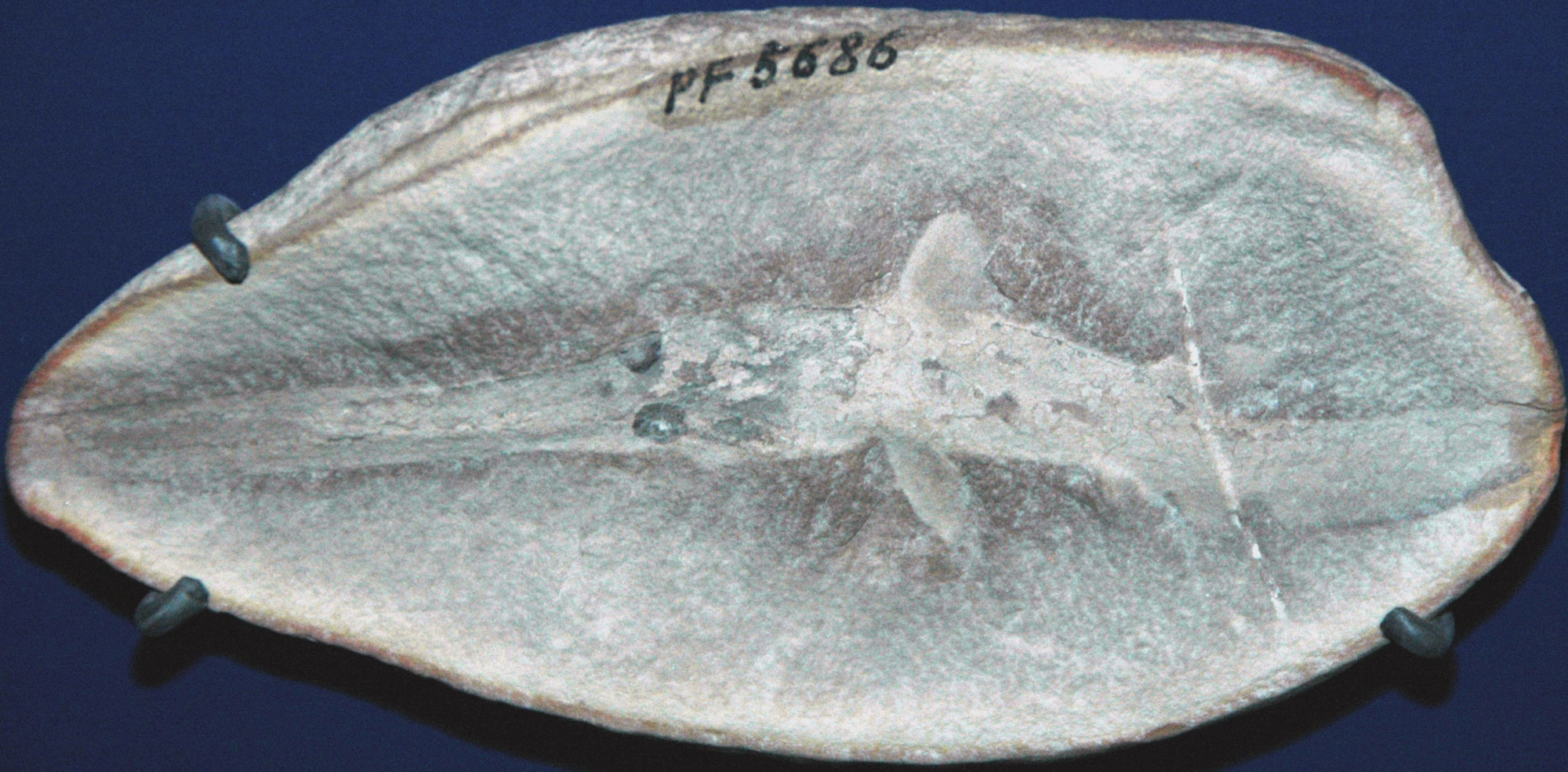

Dermal plate from a placoderm fish (Aspidichthys clavatus), Devonian Olentangy Shale, Delaware County, Ohio. Photo of USNM V 20730 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

Carboniferous fossils

During the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian, the expansion and contraction of glaciers far to the south caused sea levels to fluctuate. In the Central Lowland, these periods produced cyclothems, which are cycles of alternating marine and terrestrial rocks, often including coal. By that time, the first vertebrates had crawled onto the land, joining numerous arthropods that already lived in expansive, swampy forests. In the ocean, brachiopods, trilobites, and reef builders were decimated by the mass extinction at the end of the Devonian.

The Mississippian is sometimes known as the “Age of Crinoids” because of the increase in the abundance and diversity of crinoids, as well as starfish, edrioasteroids, urchins, and other echinoderms during this time. Sites near Crawfordsville, Indiana are world famous for containing abundant specimens of more than 60 well-preserved crinoid species. While it is common to find stem pieces of crinoids throughout the Midwest, discoveries of the head, or calyx, are much rarer. Crawfordsville provides a wealth of unbroken lengths of stem and calyxes from these filter-feeding animals. Spectacular crinoids, and shark teeth are known from both Indiana and Iowa.

A Mississippian-aged site near Delta, Iowa, has yielded some of the best-preserved examples of early land-dwelling vertebrates. For example, Whatcheeria deltae, described in 1985, is considered a “reptile-like amphibian,” having some anatomical features more like those of amphibians and some more like those of amniotes. This animal measured about 1 meter (3 feet) long, and dates to around 340 million years ago.

A crinoid (Platycrinites), Mississippian Keokuk Limestone, Montgomery County, Indiana. Photo of USNM S 6075 by Bruce Martin (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

A crinoid (Springericrinus sacculus), Mississippian Ramp Creek Formation, Montgomery County, Indiana. Photo of USNM S 5999 by Crinoid Type Image Project (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

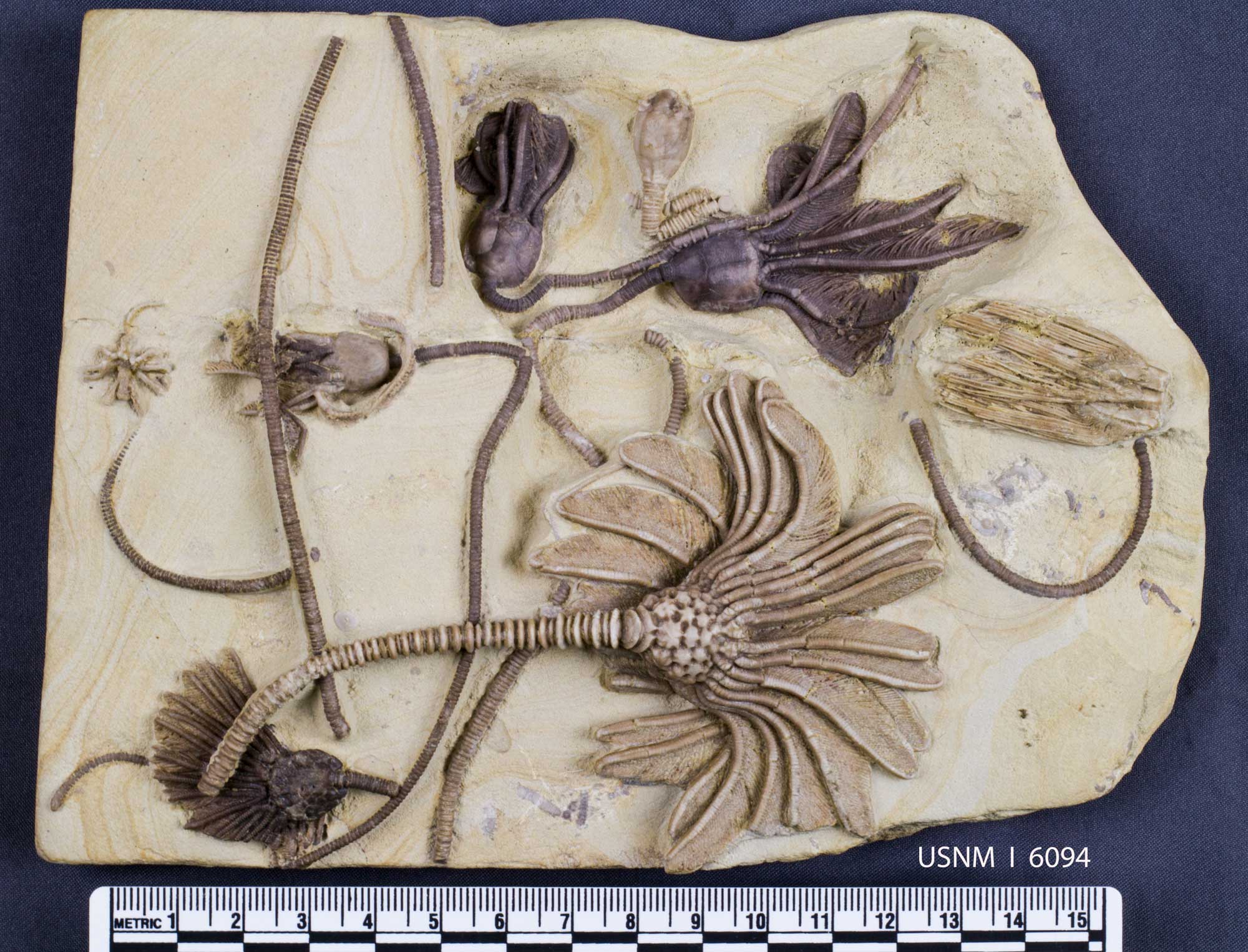

Slab of crinoids and a blastoid, Mississippian Le Grand Formation, Marshall County, Iowa. Species are Cactocrinus nodobrachiatus, Dichocrinus inornatus, Platycrinites, Rhodocrinus, and an unnamed blastoid. Photo of USNM S 6084_1 by Bruce Martin (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

A crinoid (Graphiocrinus simplex), Mississippian Burlington Limestone, Iowa. Photo of USNM PAL 351838 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

Tooth plate from a shark (Psephodus) that ate shelly invertebrates, Mississippian Warsaw Shale, Lawrence County, Indiana. Photo of USNM V 13906 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

Mazon Creek biota

The Mazon Creek lagerstätte is a fossil deposit of Pennsylvanian age exposed in coal mines in northeastern Illinois. Its hematite concretions (or nodules) preserve hundreds of terrestrial and marine plant and animal species in beautiful detail, with many found nowhere else in the world.

Mazon Creek flora

Plants in the Mazon Creek assemblage include those typical of Carboniferous forests, also known as "coal swamps." These wetland forests were home to a tangle of lycopod and sphenopsid trees, early conifers, the now-extinct seed ferns, and other plants. By the Pennsylvanian, huge lycophytes like Lepidodendron and other plants grew thickly on the Midwestern landscape. (Lycophytes survive today but only as very small plants on the forest floor, sometimes called “ground pines.”) Peat built up in these stagnant, wet environments. As plant matter accumulated for tens of millions of years, it formed thick, extensive deposits of coal underlying much of the Central Lowland as well as the parts of the Inland Basin.

Cone of an extinct lycophyte tree (Lepidostrobus), Pennsylvanian, Grundy County, Illinois. Photo of YPM PB 000679 by Fiona O'Brien (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

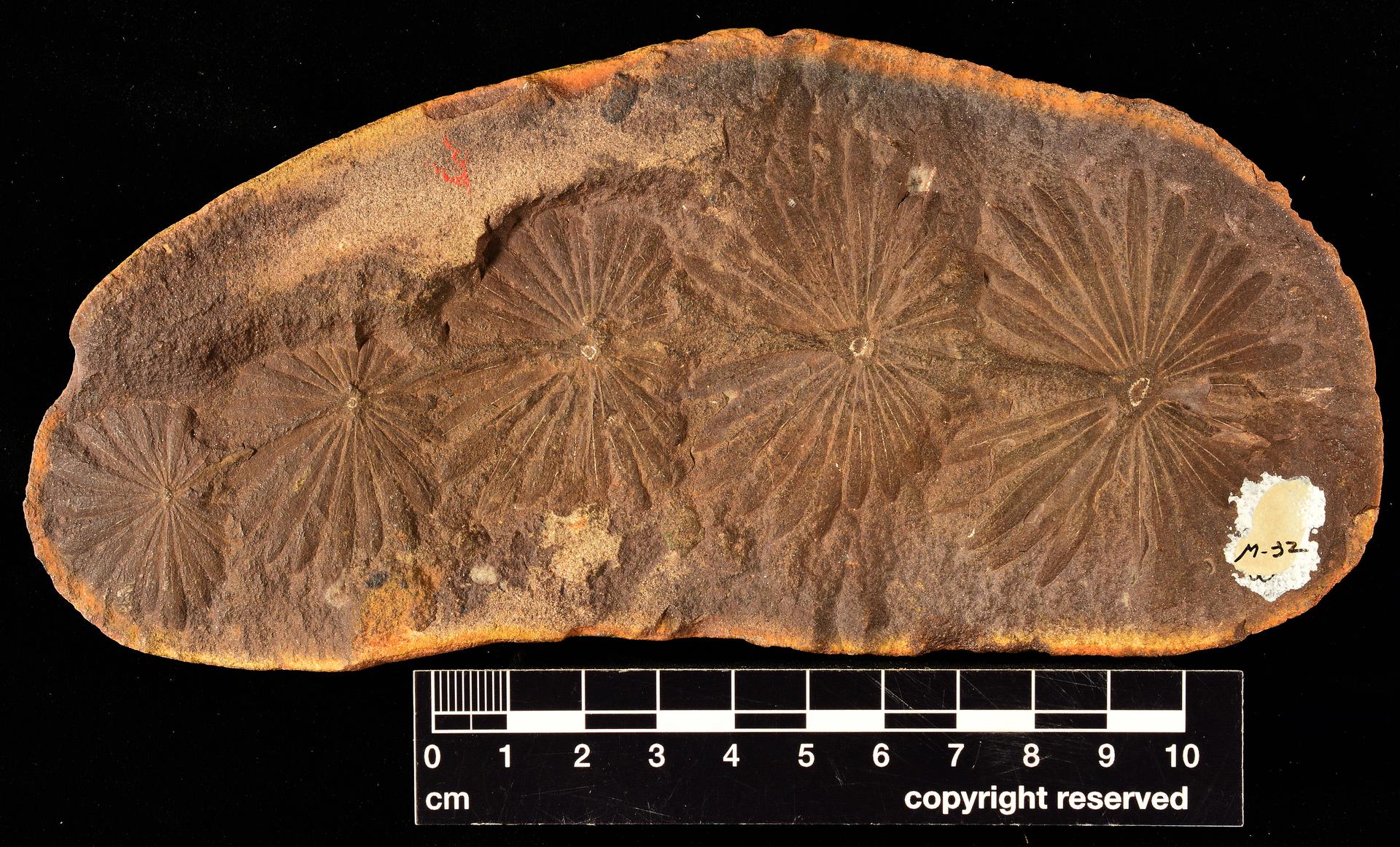

Leaves of an extinct sphenophyte tree (Annularia stellata), Pennsylvanian, Grundy County, Illinois. Photo of YPM PB 000719 by PB Staff (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

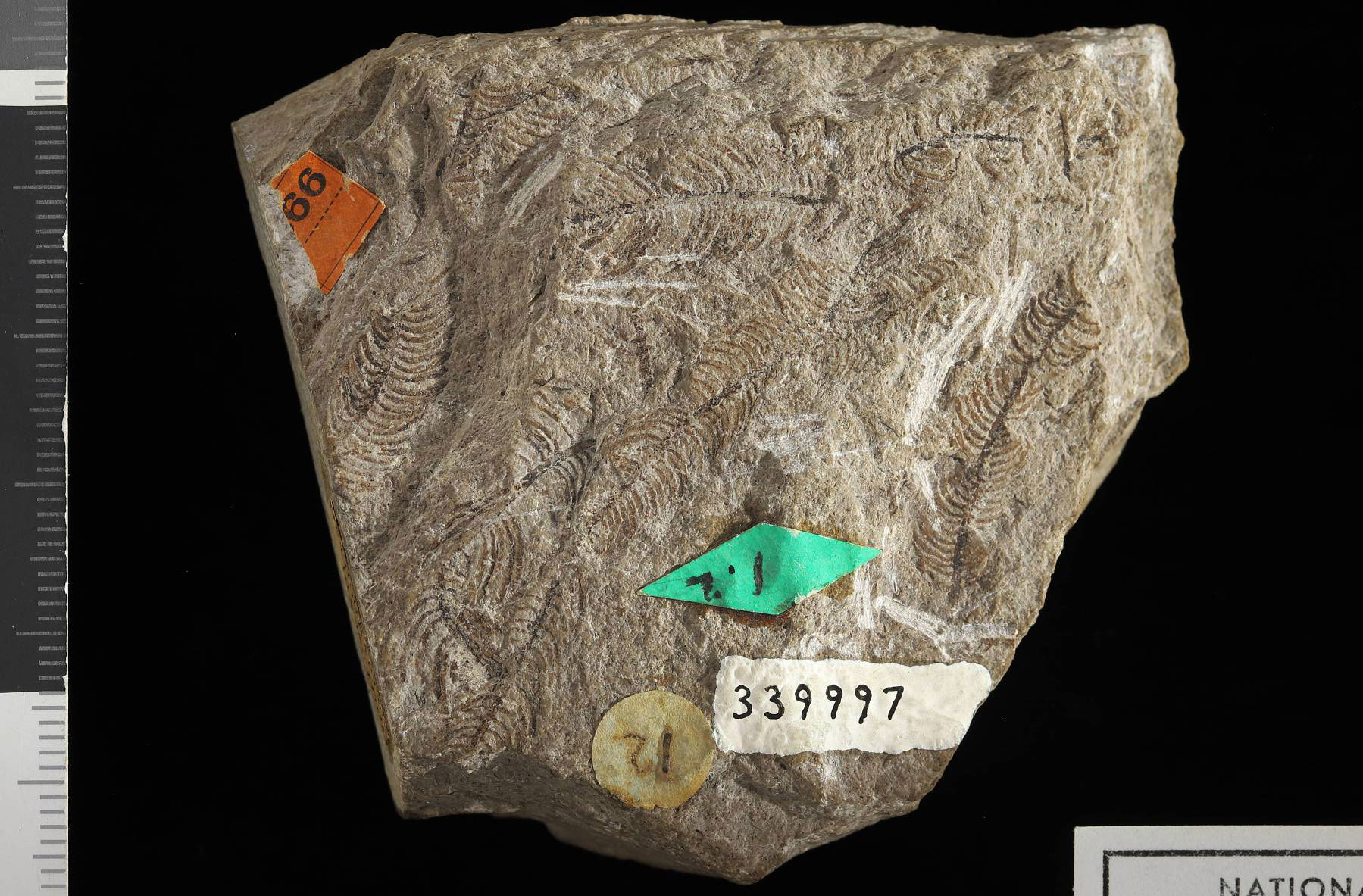

A frond of a marattioid tree fern (Pecopteris), Pennsylvanian Francis Creek Shale Member, Carbondale Formation, Illinois. Photo of USNM PAL 444624 by Chip Clark (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

A frond of a seed fern (Neuropteris flexuosa), Pennsylvanian, Illinois. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Mazon Creek fauna

Mazon creek also includes many types of animals, such as jellyfish, horseshoe crabs, crustaceans, eurypterids (sea scorpions), millipedes, insects, and bivalves. Among the amazing fossils of Mazon Creek is Illinois’ state fossil, the Tully Monster or Tullimonstrum, an unusual invertebrate that is thought to have swum using its three-finned tail and hunted using its eight-toothed proboscis to bring prey to the mouth. Its place on the tree of life is uncertain, though some scientists suspect it is a mollusk. Without the exceptionally preserved specimens at Mazon Creek, this soft-bodied predator would be unknown to science. Tully Monsters reached lengths of up to 30 cm (1 foot), but most specimens are less than half that length.

A horseshoe crab-like animal (Euproops danae), Pennsylvanian, Grundy County, Illinois. Photo of USNM PAL 386656 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

A crustacean (Acanthotelson stimpsoni), Pennsylvanian, Grundy County, Illinois. Photo of YPM IP 019903 by Yale ITS Media Services (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

A myriapod (Euphoberia granosa), Pennsylvanian, Grundy County, Illinois. Photo of YPM IP 042897 by Susan H. Butts (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

A cockroach (Megablattina beecheri), Pennsylvanian, Grundy County, Illinois. Photo of YPM IP 008412 by Yale ITS Media Services (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History on GBIF.org, CC0 1.0 Universal/public domain dedication).

A shark (Bandringa rayi), Pennsylvanian, Illinois. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

"Tully: Monster vs Method." Video by the Field Museum (via Vimeo).

Cretaceous fossils

While an expansive record of Paleozoic life is present in the Midwest, the Mesozoic Era is relatively poorly represented. Cretaceous-aged rocks in Minnesota, Iowa, and southern Illinois provide some glimpses into life during this time period. A few fragmentary dinosaur fossils have been found in riverine deposits in the lower parts of the Dakota Formation of Minnesota and Iowa. Abundant fossil leaves of flowering broadleaf plants have been found in the Dakota Formation of south-central Minnesota.

Later layers were deposited under marine conditions, as the huge Western Interior Seaway invaded farther into the upper Midwest. In Iowa, these marine strata (including the Graneros, Greenhorn, Carlile, and Niobrara formations) have yielded a few bones of large sea reptiles called plesiosaurs. In southern and western Minnesota, similar layers have produced shark teeth, sea turtles, and scattered marine invertebrates, including ammonites, bivalves, and microfossils (foraminifera). Fragments of a Creatceous crocodile (Terminonaris robusta) and teeth of a crow shark (Squalicorax) have been found In the Mesabi Iron Range of northeastern Minnesota.

Gastropods from the Late Cretaceous Coleraine Formation, Calumet, Minnesota. Photo by Rylan Bachman (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Crow shark tooth (Squalicorax), Late Cretaceous Coleraine Formation, Calumet, Minnesota. Photo by Rylan Bachman (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Pleistocene fossils

About 2.6 million years ago, permanent ice sheets formed in the Northern hemisphere, marking the beginning of the Quaternary period (which extends to the present). During this time, glaciers repeatedly scraped their way southward across the Midwest and melted back northward. Some gaps in the fossil record in the region are due to glaciers eroding bedrock away.

The glaciers began to retreat from the Midwest about 15,000 years ago, leaving behind the landscape we see today, as well as the sediment in which we find fossils and sometimes human artifacts. Many fossils from the Quaternary are found in pond and stream sediment dating from the receding of glaciers. As the glaciers melted away from the Midwest, some of the geographic features they created filled with water and formed many of the lakes and ponds present in the region today. Many bodies of water left by the glaciers have since been filled with sediment and are virtually invisible at the surface. When flooding or construction exposes these pond sediments, the organisms preserved in them are suddenly revealed.

Nearly all glacial-age ponds contain a rich fossil record of small freshwater mollusks, pieces of wood, pollen, and seeds, many of which increased over time as plant communities recolonized land freed from the ice. Since the form of pollen indicates the kind of plant it came from, the pollen record can give a detailed account of how vegetation moved into an area as the climate changed. As plants returned, so did large animals: large vertebrate remains include those of mammoths, mastodons, giant beavers, peccaries, tapirs, foxes, bears, seals, deer, caribou, bison, and horses. Numerous mastodon skeletons have been found throughout the Midwest.

Pleistocene spruce (Picea) seed cones mixed with gastropod shells, Oakland County, Michigan. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

A beaver skull (Castoroides ohioensis), Pleistocene, Cass County, Indiana. Photo of USNM V 1634_1 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

A bear skull (Ursus procerus), Pleistocene, Butler County, Ohio. Photo of USNM V 4214 by Michael Brett-Surman (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, CC0/public domain).

An American mastodon (Mammut americanum), Pleistocene, DeKalb County, Indiana. Photo by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland (covers the Central Lowland in Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-cl/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northeastern U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland and Inland Basin (covers the Central Lowland and Inland Basin in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont): https://earthathome.org/hoe/ne/fossils-cl-ib/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the South-central U.S.: Fossils of the Central Lowland and Interior Highland (covers the Central Lowland in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sc/fossils-cl-ih/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/

Pennsylvanian Atlas of Ancient Life, Midcontinent United States (Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas): https://pennsylvanianatlas.org/