Spotlight: Overview of the rocks of the Coastal Plain region of the South-Central United States, including Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri.

Topics covered on this page: Overview; Arkansas, Missouri, and Louisiana; Mississippi; Texas; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text of this page is derived from "Rocks of the South Central US" by Richard A. Kissel, Alex F. Wall, and Andrielle N. Swaby, chapter 2 in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the South Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2021–2023. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated September 20, 2023.

Image above: Kisatchie Falls, Louisiana. Photograph by Jim Dollar (Flickr; Creative Commons; image cropped and resized).

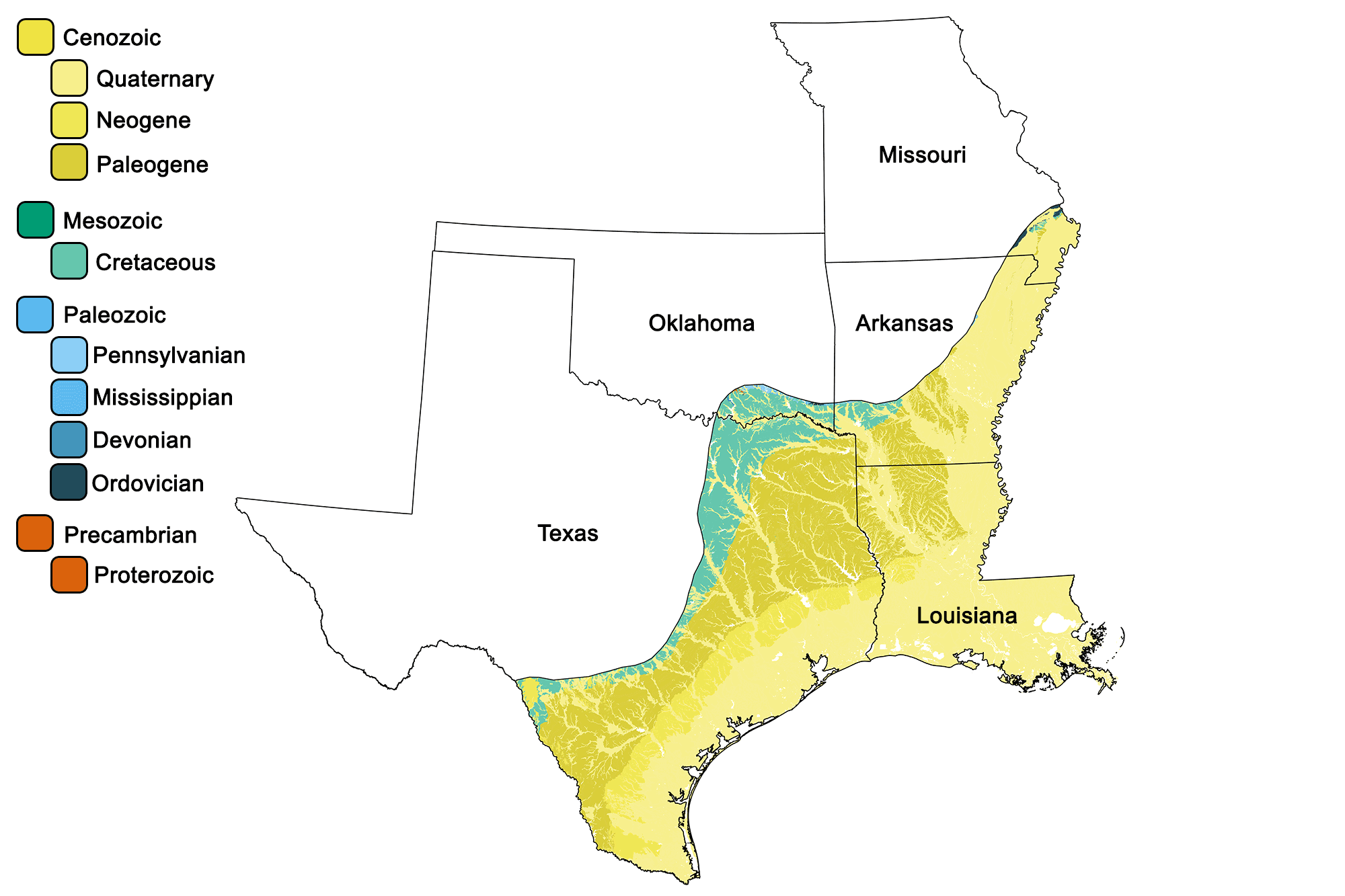

Geologic map of the Coastal Plain region of the South-Central United States showing maximum ages of mappable units. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Earth@Home project developed using QGIS and USGS data (public domain) from Fenneman and Johnson (1946) and Horton et al. (2017).

Overview

After the breakup of Pangaea during the Mesozoic, the North American plate drifted away from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Decreased tectonic activity along the continent’s eastern and southeastern edge led to the formation of a passive continental margin. The Coastal Plain extends along this margin, across the Gulf of Mexico and up through the Mississippi Embayment. The sediment and rock of the Coastal Plain is geologically very young, ranging in age from the Cretaceous to the present.

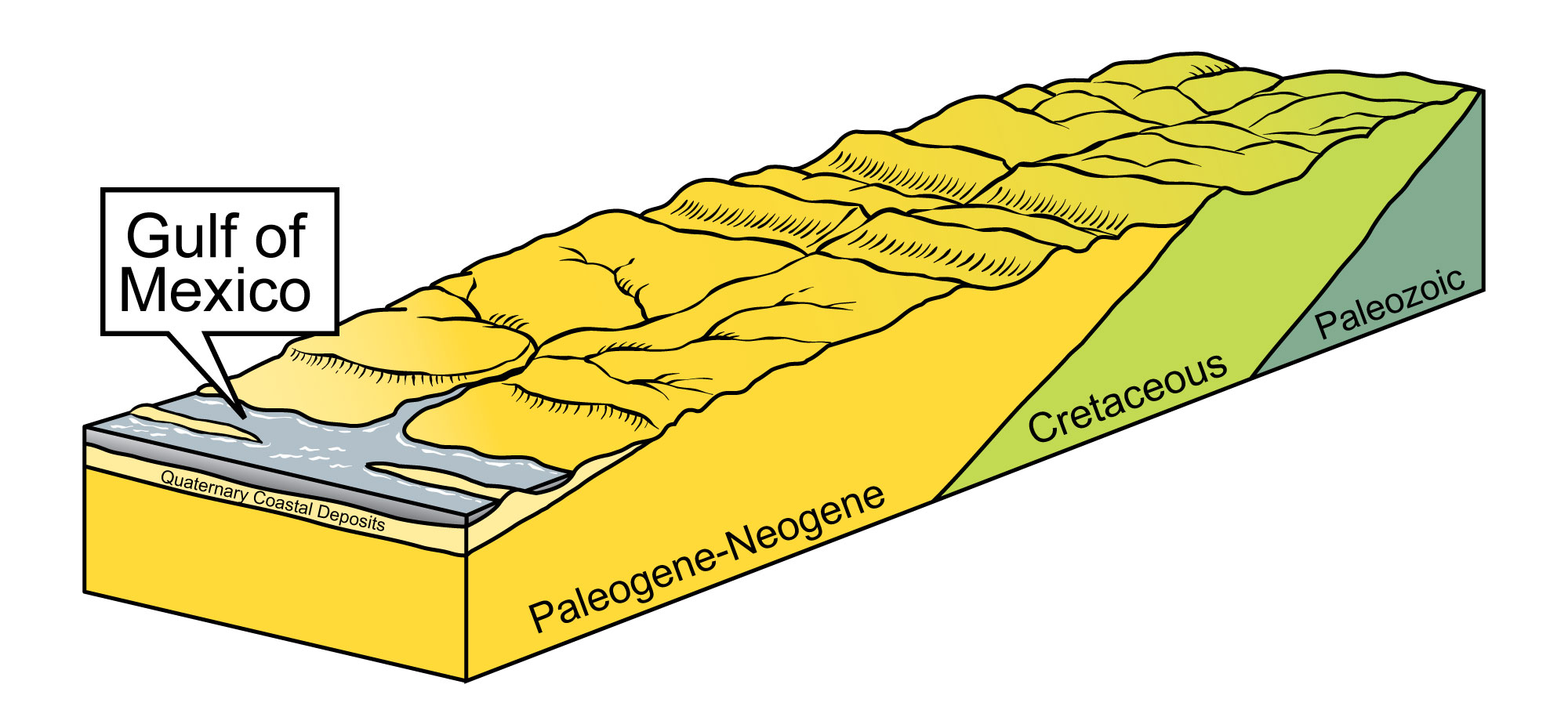

The region’s sediment and rock include gravel, sand, silt, clay, marl, limestone, and uncommon layers of concentrated shell material called coquina. Much of the Coastal Plain’s “rock” is unconsolidated sediment that has not had enough time to be lithified, cemented, or sufficiently compacted into hard rock. Coastal Plain sediment forms a wedge of gently dipping layers of sediment and sedimentary rock that thickens towards the Gulf of Mexico, overlying older bedrock.

Millions of years of sediment accumulation in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean caused coastal areas to subside, creating a gentle slope toward the ocean.

This sediment is 6100 meters (20,000 feet) thick in northern Louisiana, thickens to 12,000 meters (40,000 feet) at the coast, and reaches 18,000 meters (60,000 feet) offshore. Depending on the rates of cementation or compaction, it may take tens or even hundreds of millions of years before these layers of sediment are lithified.

Arkansas, Missouri, and Louisiana

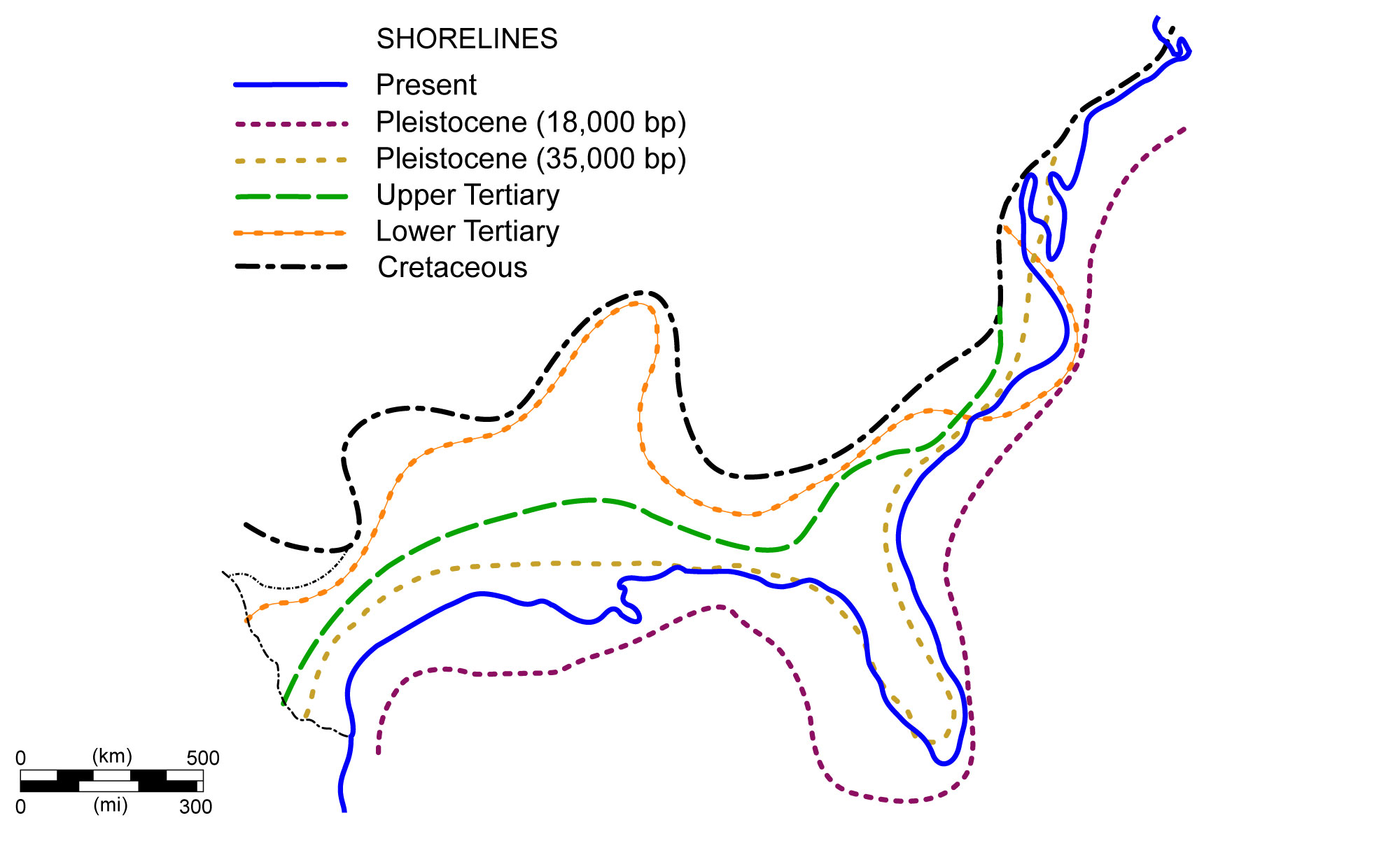

The Coastal Plain surface and subsurface sediments of Arkansas, Missouri, and Louisiana are dominated by those deposited in alluvial or deltaic settings. This indicates that a major river system, such as the Mississippi, has existed since the initial formation of the Gulf of Mexico (which occurred during the breakup of Pangaea in the Mesozoic). A progression of fluvial, deltaic, and coastal deposits carrying sediments eroded from the Ouachitas has migrated into the Gulf over time, continually altering the coastline.

Shoreline positions along the United States Coastal Plain during the past 70 million years. Image modified from original by NOAA (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

The state of Louisiana formed as a slow regression in sea level allowed the deposition of sediment to create a terrestrial environment at the edge of the Gulf. Approximately 25% of the state’s northern surface, consists of Paleogene and Neogene-aged shales, sandstones, and gravels deposited within fluvial, deltaic, and shallow marine settings.

The Kisatchie National Forest in north-central Louisiana contains some of the state’s oldest sediment, including Paleogene and Neogene silt, gravel, and shale. Photograph by Andy Milford (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license; image resized).

The remaining 75% of the surface consists of Quaternary-aged silts, sands, and gravels deposited from channels, marshes, levees, and terraces.

Mississippi River

Thousands of feet of salt are present under the fluvial deposits of the Mississippi River. This thick layer of salt accumulated during the initial formation of the Gulf when flooding and evaporation occurred during the early stages of Pangaea’s breakup. Since the salt deposits are less dense than sandy and muddy sediments, they moved plastically and vertically to form salt domes, some of which reach to and are exposed at the surface today. Louisiana’s few Cretaceous-aged outcrops, in Bienville Parish, consist of older marine deposits that were uplifted by the formation of these salt domes.

Texas

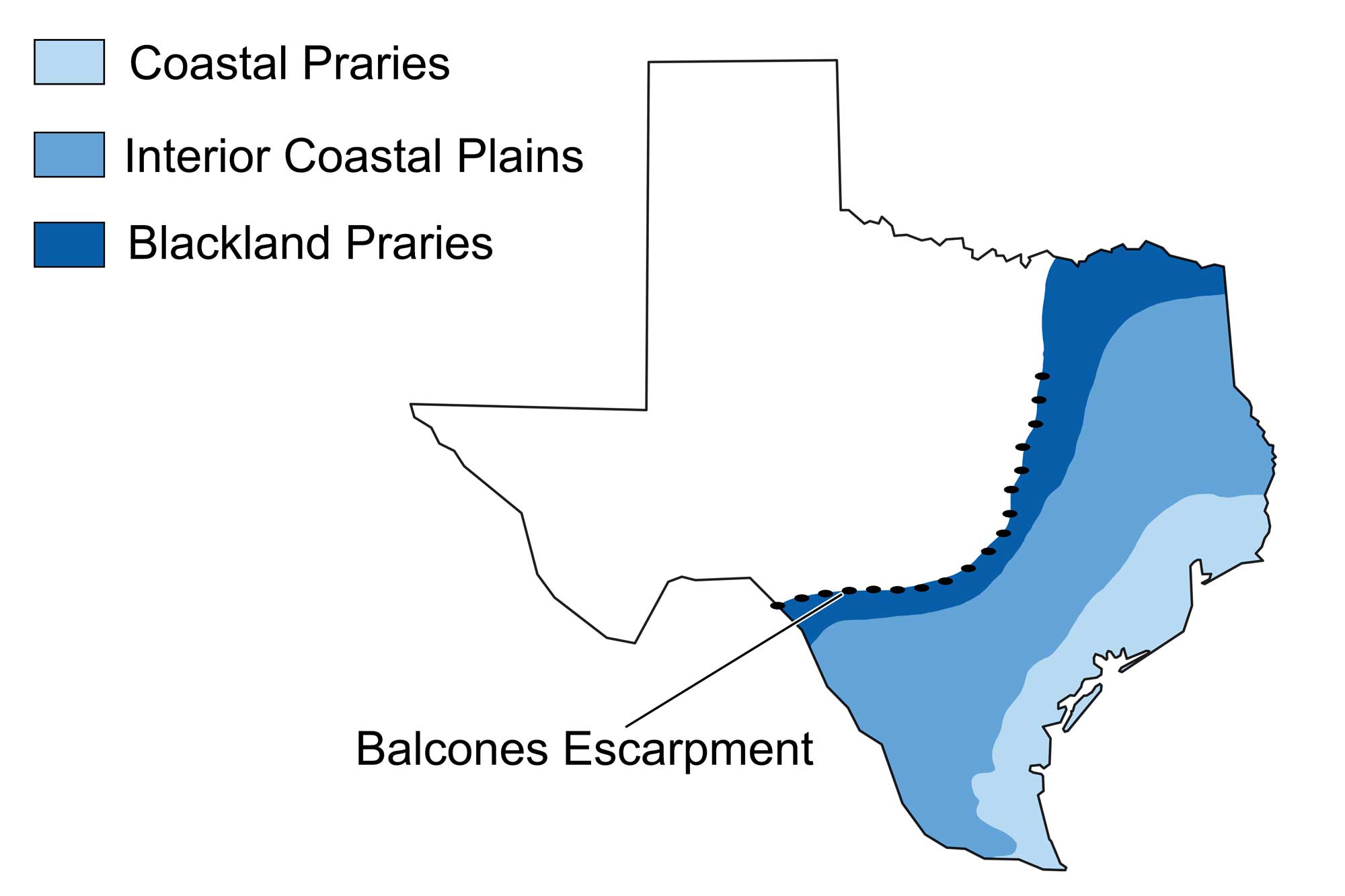

In Texas, the Coastal Plain is subdivided into several physiographic provinces: the Coastal Prairies, the Blackland Prairies, and the Balcones Escarpment.

Physiographic map of the Coastal Plain region of Texas. Image modified from original by Wade Greenberg-Brand, which in turn is adapted from image by the Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin.

The Coastal Prairies along the Gulf of Mexico are dominated by Pleistocene deltaic sands, silts, and clays. Ever since our modern sea level was reached some 3000 years ago, thin coastal-barrier, lagoon, and delta sediments have been deposited along the Coastal Prairies. Further inland, along the Interior Coastal Plains, Cenozoic clay, shales, and uncemented sands are present, overlying Pliocene limestone. In the innermost part of the Coastal Plain (the Blackland Prairies), chalks and marls are present.

The Balcones Escarpment forms the western boundary of Texas’ Coastal Plain, and extends from approximately Dallas to San Antonio. It is the surface expression of the Balcones Fault—a fault system that is thought to have formed 300 million years ago during the Ouachita Orogeny. The escarpment features cliffs that expose walls of Cretaceous limestone, as well as subterranean caves.

Rocks of the Balcones Escarpment exposed at the top of Mount Bonnell in Austin, Texas. Photograph by Omar Maya (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license; image cropped and resized).

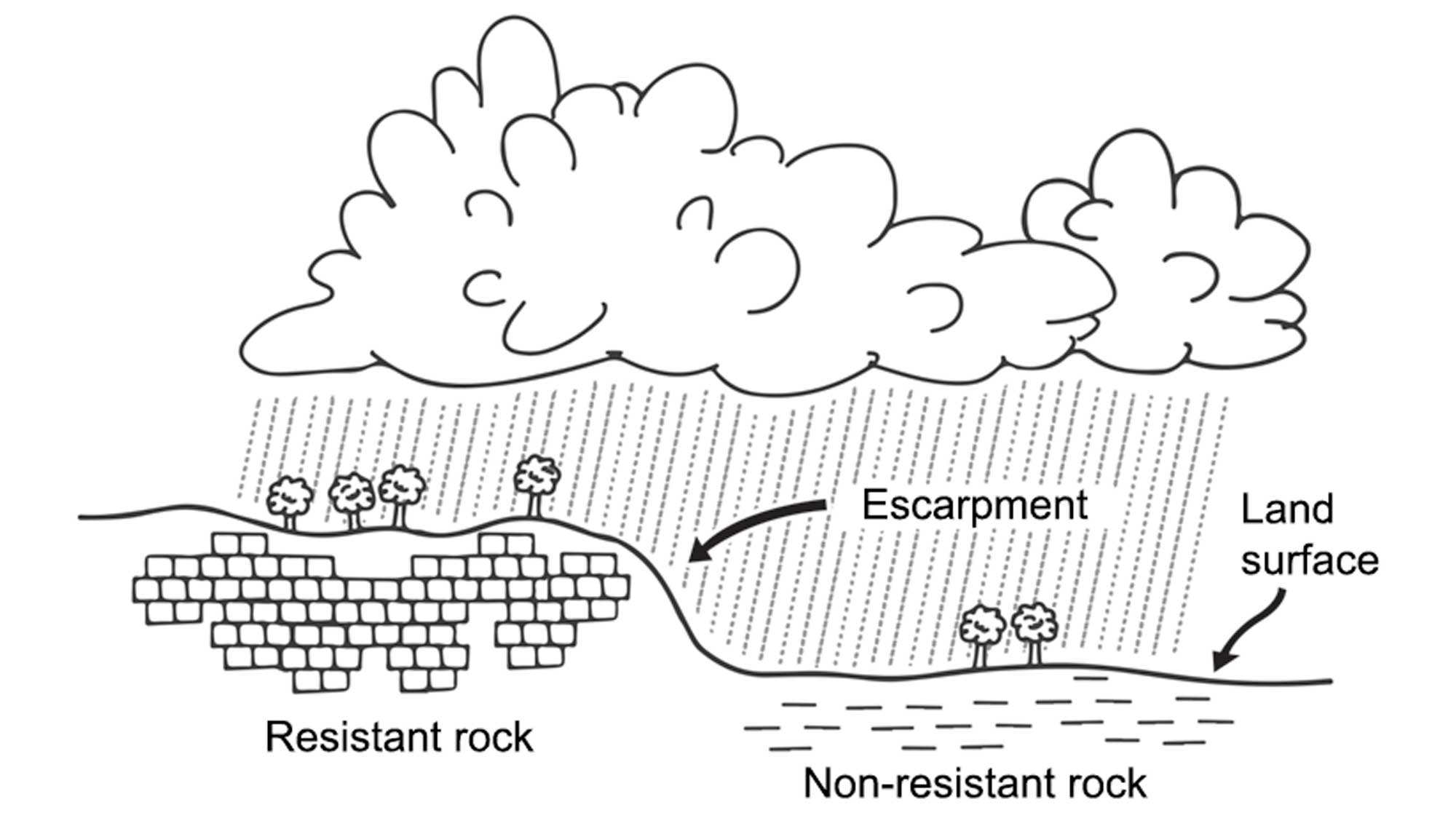

The rocks to the west of the Balcones Escarpment are more resistant to erosion than the soft sediments of the Coastal Plain. As a result, erosion and weathering have served to accentuate the Escarpment’s height.

The Balcones Escarpment and its surrounding environments have been shaped by erosion. Image modified from original by Wade Greenberg-Brand.

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution

Digital Encyclopedia of Earth Science: Minerals: https://earthathome.org/de/minerals/

Earth@Home: Here on Earth: Rocks: https://earthathome.org/hoe/rocks/

Earth@Home Virtual Collection: Rocks: https://earthathome.org/vc/rocks/ (Virtual rock collection featuring 3D models of rock specimens sorted by type.)

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northeastern U.S.: Rocks of the Coastal Plain (continues coverage of the Atlantic Coastal Plain in Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York): https://earthathome.org/hoe/ne/rocks-cp/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southeastern U.S.: Rocks of the Coastal Plain (continues coverage of the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia): https://earthathome.org/hoe/se/rocks-cp/