Page snapshot: Introduction to the fossils of the Basin and Range region of the south-central United States.

Topics covered on this page: Paleozoic fossils; Mesozoic fossils; Cenozoic fossils; Resources.

Credits: Most of the text on this page comes from "Fossils of the South Central US" by Warren D. Allmon and Alex F. Wall, chapter 3 in the The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the South Central US, edited by Mark D. Lucas, Robert M. Ross, and Andrielle N. Swaby (published in 2015 by the Paleontological Research Institution; currently out of print). The book was adapted for the web by Elizabeth J. Hermsen and Jonathan R. Hendricks in 2022. Changes include formatting and revisions to the text and images. Credits for individual images are given in figure captions.

Updates: Page last updated August 26, 2022.

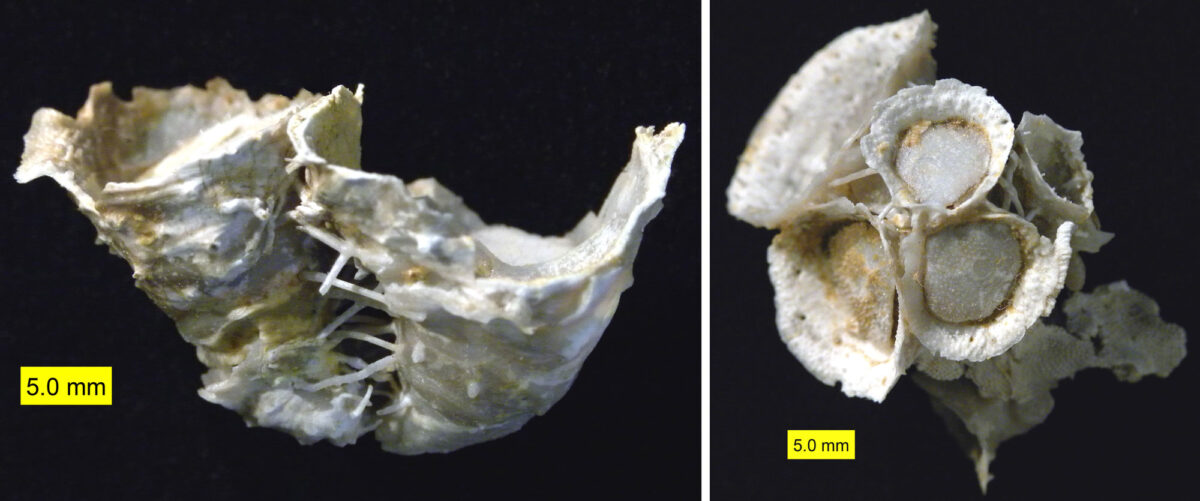

Image above: Productid brachiopods (Hercosestria cribrosa) from the Permain Glass Mountains of Texas. Left photo and right photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Paleozoic fossils

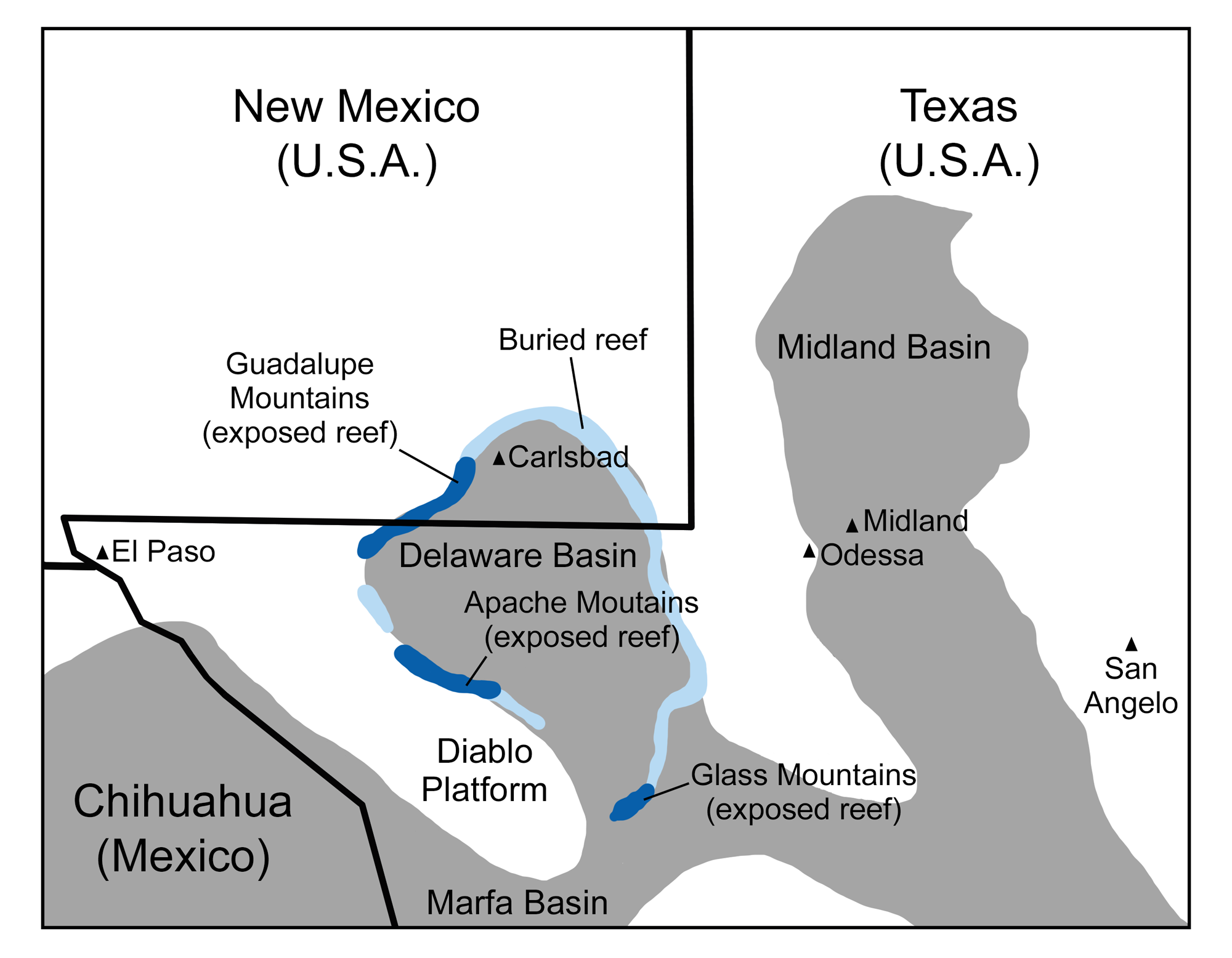

The portion of the Basin and Range region in far western Texas includes most of “Big Bend Country,” a name frequently used for westernmost Texas. The oldest rocks here date to the Permian, when three “fingers” of a shallow sea created tropical marine basins in New Mexico and western Texas. A fossilized reef formed on the Permian shoreline of the Delaware Basin, built largely by algae, sponges, brachiopods, and bryozoans.

Permian reefs of Texas: Map showing the paleogeographic relationship of the reefs to the topographic lows and highs of the shallow sea that covered the Texas-New Mexico-Chihuahua region in the Permian. The reef occupied the rim of the Delaware Basin. Original map by Wade Greenberg-Brand, modified for the Earth@Home project.

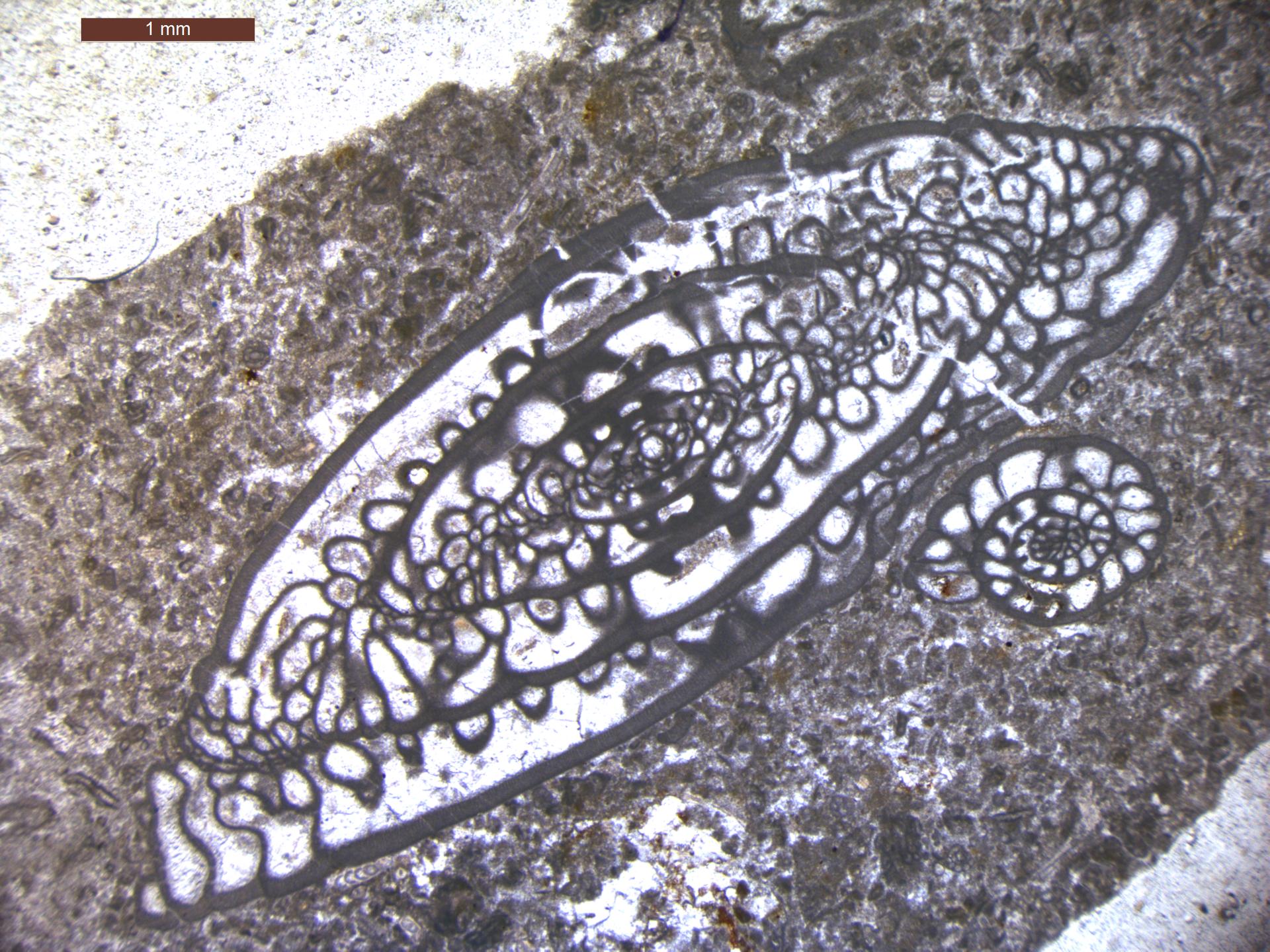

Like modern reefs, this reef complex was built from the shells of marine invertebrates. Most of the shells were made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which has the same composition as limestone. This reef complex also provided a haven for a great variety of other animals: corals, crinoids, cephalopods, fusilinids (unusually large forams), and gastropods thrived there. After the reef was buried by sediment, much of its calcium carbonate was replaced by other minerals dissolved in groundwater. The most important of these minerals was silica (SiO2), which has the same composition as glass. The resulting “glass” fossils can be freed from their surrounding limestone by treating the rock with acid, which dissolves the rock but leaves the delicate fossils behind.

In addition to invertebrates and forams (which are single-celled organisms that are protists, not animals), tooth whorls of the enigmatic shark Helicoprion have been found in the Glass Mountains. No one knows exactly how these tooth whorls fit into the mouths of these ancient sharks, since only the whorls are usually found. Many different attempts have been made to reconstruct the living animals.

A fossil sponge from the Permian of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas. Photo Jennifer Trout (National Park Service, public domain).

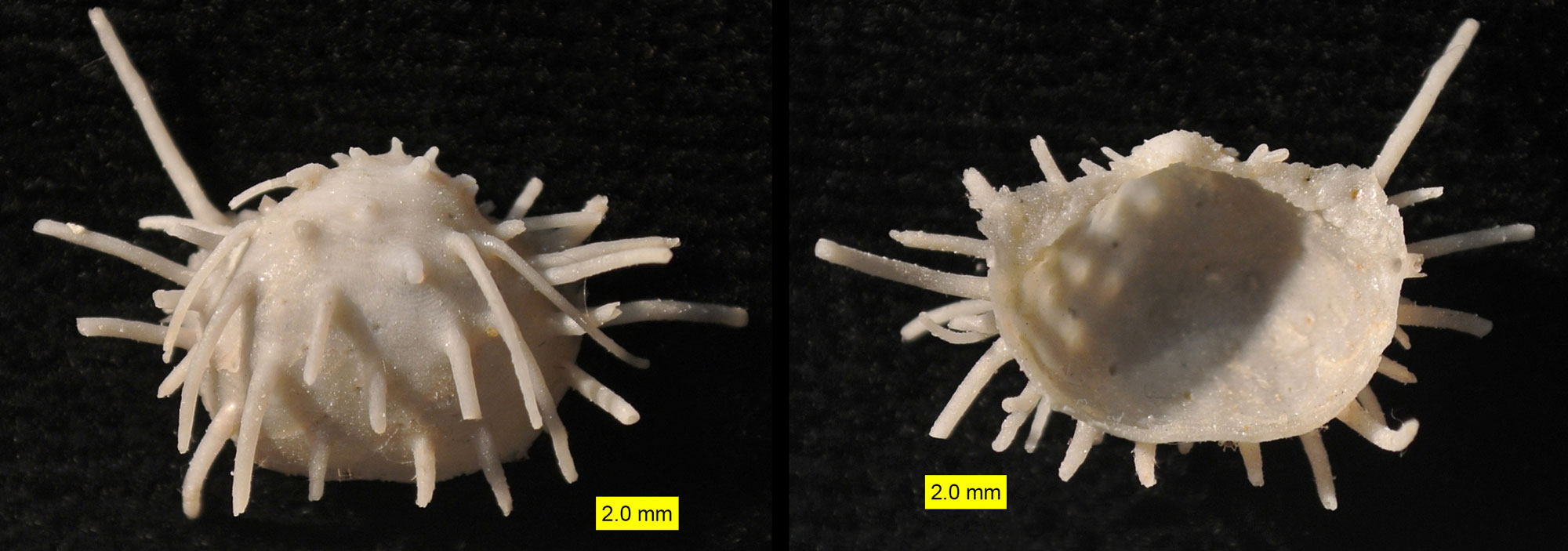

Two views of a productid brachiopod shell, middle Permian, Glass Mountains, Texas. Left photo and right photo by Mark A. Wilson (Wilson44691, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

3D model of a productid brachiopod, Permian, Glass Mountains, Texas. Longest dimension in 4 cm (about 1.6 inches). Model of PRI 76879 by Jaleigh Pier, from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution (Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Bryozoans, Permian, Leonard Formation, Glass Mountains, Brewster County, Texas. Top left: Unidentified bryozoan (YPM IP 176064, photo by Jessica Utrup, 2015). Bottom left: Unidentified bryozoan (YPM IP 791535, photo by Eric Peavey, 2015). Right: Acanthocladia (YPM IP 175652, photo by Susan H. Butts, 2020). Specimens from Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, images from GBIF.org).

Photomicrograph (a photograph taken under a microscope) of forams from the Permian Hueco Canyon Formation, Hudspeth County, Texas. This photo is of a thin section, or a slice of the rock that has been prepared so that the inner structure of the forams can be viewed under a microscope. Photos of YPM IP 022789 by Eileah Sims, 2019 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Tooth whorl of Helicoprion ferrieri, Permian, Skinner Ranch Formation, Glass Mountains, Brewster County, Texas. Photos by James St. John (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Mesozoic fossils

Following the Permian, there is a roughly 150-million-year gap in Big Bend Country’s fossil record. The next oldest fossils in the region are from the Late Cretaceous and record a very different scene. More than 100 million years ago, the area was covered by the Western Interior Seaway. Fossilized mollusks, echinoderms corals, fish, shark teeth, and giant marine reptiles, including mosasaurs, are found in the oldest layers.

Two views (end and side) of an unidentified echinoid, Early Cretaceous, Pecos County, Texas. Photo of YPM IP 340196 by Christina Lutz, 2017 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, via GBIF.org).

3D model of an echinoid (sea urchin, Stereocidaris hudspethensis), Cretaceous Washita Group, Hudspeth County, Texas. Model of PRI 50632 by Emily Hauf, specimen on display at the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York (Digital Atlas of Ancient Life on Sketchfab, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

Early Cretaceous foam oysters (Grphyaeidae) from Pecos County, Texas. Left: Gryphaea, also called the devil's toenail (YPM IP 340204). Right: Exogyra texana (YPM IP 340198). Photos by Christina Lutz, 2017 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, via GBIF.org).

The ammonoid Mortoniceras, Early Cretaceous, Fredericksburg Group, Pecos County, Texas. Photos of YPM IP 340212 by Christina Lutz, 2017 (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/YPM, CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication, via GBIF.org).

The somewhat younger Aguja Formation represents a swampy coal forest and contains a diversity of fossil plants (such as the fan-palm Sabal), ammonites, turtles, 60 species of dinosaurs, and Deinosuchus—a giant crocodilian up to 10.6 meters (35 feet) long.

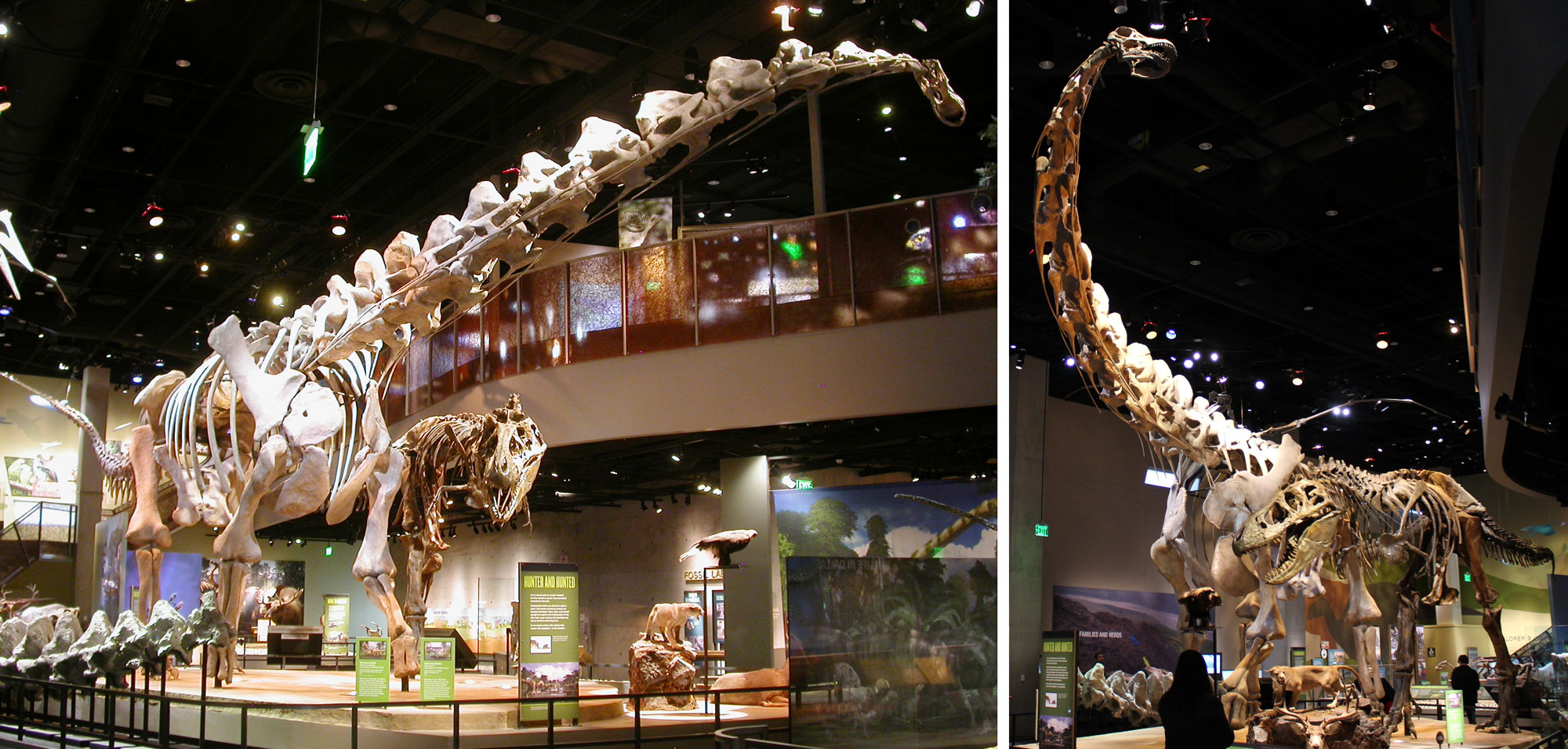

The overlying Javelina Formation is thought to record the boundary between the end of the Cretaceous and the Paleogene. Like the Aguja, this formation preserves the remains of a coastal “coal forest,” and it preserves a variety of famous reptiles including Tyrannosaurus rex, Alamosaurus (perhaps the largest dinosaur known from North America), and the giant pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus.

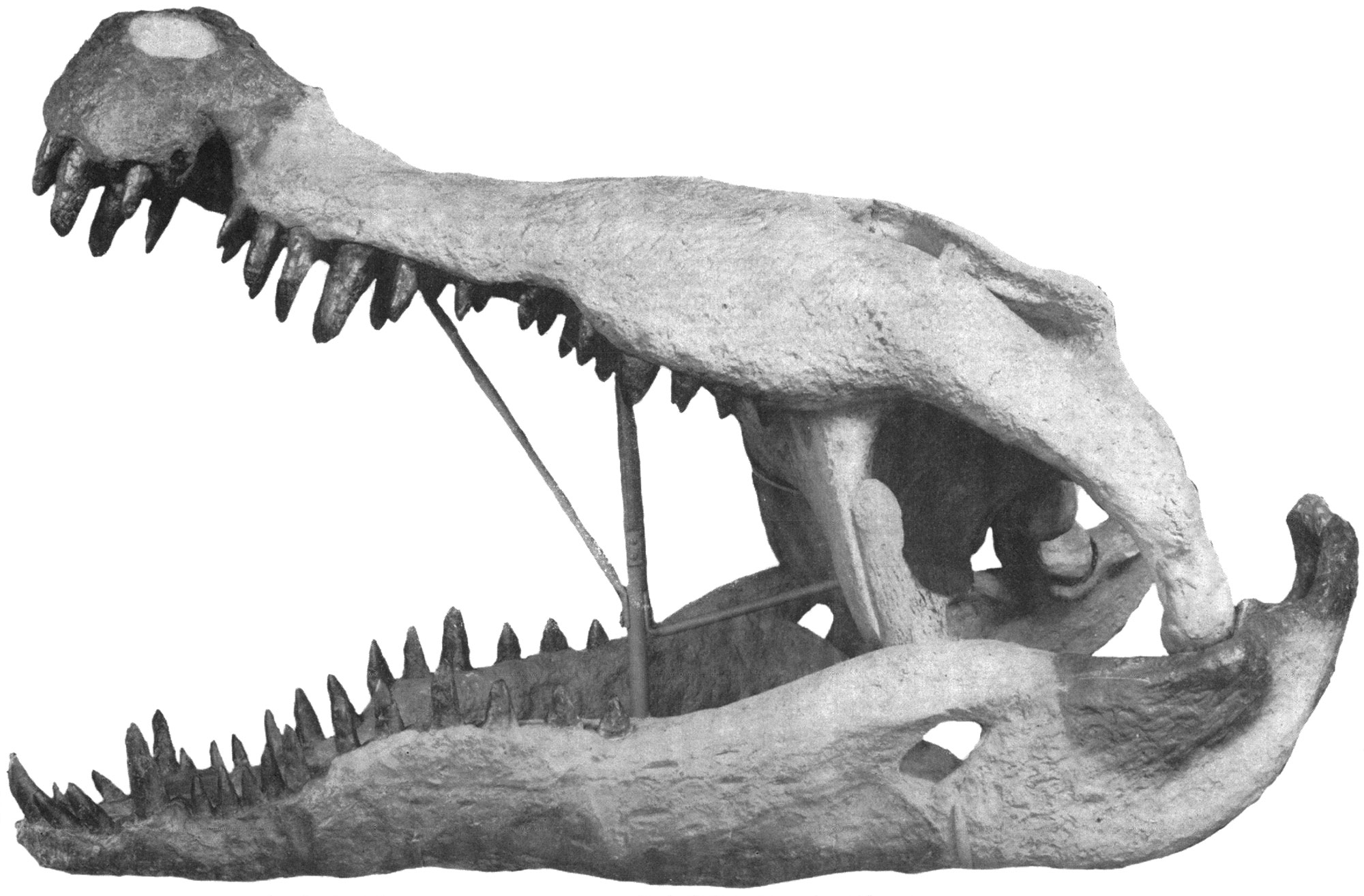

Skull of Deinosuchus riograndensis, an ancient crocodilian, Late Cretaceous, Aguja Formation, Big Bend National Park, Texas. Photo from E. H. Colbert and R. T. Bird (1954) American Museum Novitates (Wikimedia Commons, public domain in the United States according to information on Wikimedia).

Two views of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis and Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons on display at the Perot Museum in Dallas, Texas. Left photo by Dr. Matt Wedel (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized); right photo by Rodney (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Excavation of the vertebrae of a large sauropod dinosaur, possibly Alamosaurus, at Big Bend National Park, 1999. Left: A field crew putting a plaster jacket on the bones, which protects and stabilizes them for transport. Photo source: U.S. National Park Service (public domain). Right: Members of a field team carrying a bone; this bone weighed about 475 pounds. Photo source: U.S. National Park Service (public domain).

Excavation of the vertebrae of a large sauropod dinosaur, possibly Alamosaurus, at Big Bend National Park, 2001. Left: A field crew lifting a plaster jacket containing bones. Photo source: U.S. National Park Service (public domain). Right: A helicopter transporting a large plaster jacket containing seven vertebrae; this jacket was flown to a truck. Photo source: U.S. National Park Service (public domain).

Quetzalcoatlus northropi. Left: Cast (reproduction) skeleton on display at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Photo by Yinan Chen (Wikimedia Commons, public domain dedication). Right: Reconstructions of Quetzalcoatlus foraging on the ground. Illustration from M. P. Witton and D. Naish (2008) PLoS ONE 3(5): e2271 (Creative Commons Attribution license, image cropped and resized).

Cenozoic fossils

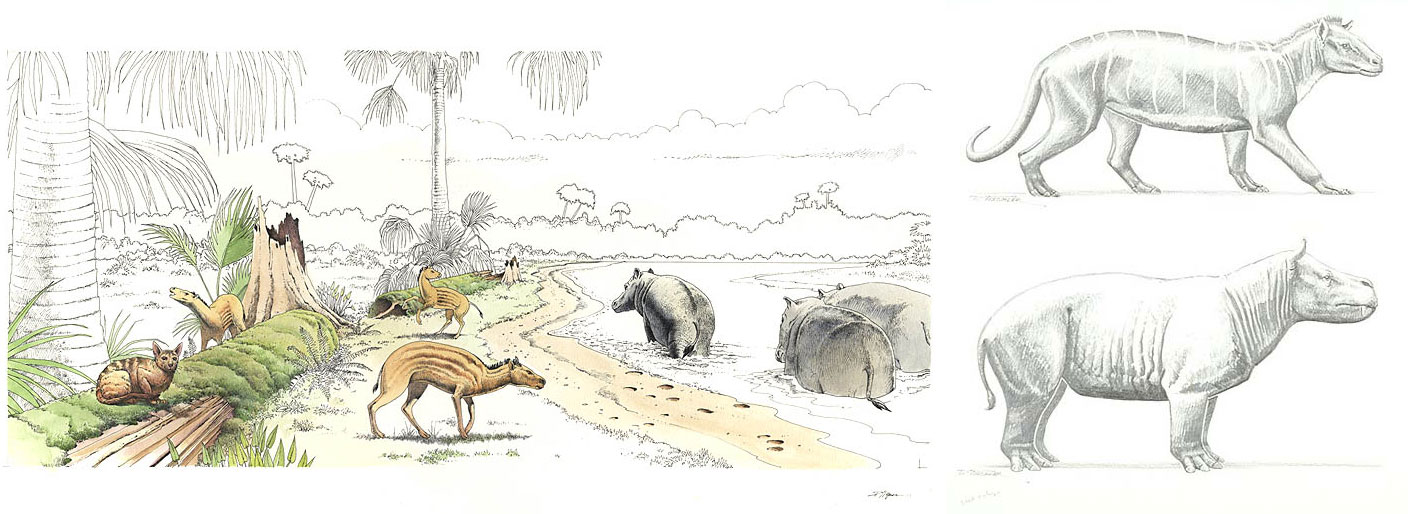

Some layers of early Paleogene terrestrial sediments (e.g., the Tornillo Formation) found in Big Bend Country preserve a snapshot of life on land around between 65 and 50 million years ago, including fish, reptiles, and mammals.

Big Bend National Park in the Paleogene. Left: Reconstruction of the park in the Eocene, featuring Protorohippus (an ancient horse, about 35 centimeters or 14 inches high at the shoulder, center foreground), Coryphodon (right, in the water), and Uintacyon (left, on the log). Art by Robert Hynes (U.S. National Park Service, public domain). Top right: Phenacodus, about 60 centimeters (24 inches) high at the shoulder. Art by Doris Tischler (U.S. National Park Service, public domain). Bottom right: Coryphodon, about 1 meter (3.3 feet) high at the shoulder. Art by Doris Tischler (U.S. National Park Service, public domain).

Resources

Resources from the Paleontological Research Institution & partners

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life, Western Interior Seaway (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Wyoming): https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/geology/

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Virtual Collection: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (Virtual fossil collection featuring 3D models of fossil specimens sorted by group)

Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Northwest-central United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin in Range in southeastern Idaho): https://earthathome.org/hoe/nwc/fossils-br/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin and Range in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/fossils-br

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Western United States: Fossils of the Basin and Range (continues coverage of the Basin and Range in California, Nevada, and Oregon): https://earthathome.org/hoe/w/fossils-br/

Earth@Home: Earth Science of the Southwestern United States: Fossils of the Great Plains (more about fossils from the Permian reef complex in southeastern New Mexico and western Texas): https://earthathome.org/hoe/sw/fossils-gp/

Earth@Home: Quick guide to common fossils: https://earthathome.org/quick-faqs/quick-guide-common-fossils/